Introduction

The impact upon mental health of the financial austerity measures introduced by many countries post-2008 is increasingly recognised (Edmiston et al., Reference Edmiston, Patrick and Garthwaite2017), as is the association between increased financial stress and increased depression (Guan et al., Reference Guan, Guariglia, Moore, Xu and Al-Janabi2022). Where such measures have included changes to financial benefits systems, individuals engaged with those systems have reported adverse outcomes including discrimination, shame, humiliation, hopelessness, and social isolation (Garthwaite, Reference Garthwaite2014; Saffer et al., Reference Saffer, Nolte and Duffy2018; Samuel et al., Reference Samuel, Alkire, Zavaleta, Mills and Hammock2018).

In the United Kingdom, the Personal Independence Payment (PIP) replaced Disability Living Allowance (DLA) in 2013. Qualifying criteria became narrower, making it more difficult to claim (Machin, Reference Machin2017). PIP was ostensibly designed to help people with long-term illnesses, disabilities or mental health conditions, and is usually conditional upon periodic medical assessment interviews, conducted by a registered healthcare professional on behalf of the UK Department of Work and Pensions (DWP). All such work is contracted by the DWP to private-sector partners (DWP, 2022a). Criticisms of the PIP process include delays in waiting times for assessment (in July 2022, the wait was reported as an average of five months); delays in the completion of claims; a lack of appropriately qualified medical staff to conduct interviews; and the involvement of private companies generally (Citizens Advice, 2022; Pring, 2020; Benefits and Work, 2022; Disability Rights UK, Reference Disability Rights2020). In a thematic analysis, Porter et al. (Reference Porter, Pearson and Watson2021) highlight how ostensibly objective assessments can reinforce existing societal inequalities, disadvantaging those without access to personal, social and economic resources. Further concerns have been raised that benefit assessments are overly medicalised, focused on physical disability, and do not capture claimants’ experiences of mental ill-health (Baumberg et al., Reference Baumberg, Warren, Garthwaite and Bambra2015; Shefer et al., Reference Shefer, Henderson, Frost-Gaskin and Pacitti2016, Pybus et al., Reference Pybus, Pickett, Lloyd, Prady and Wilkinson2021).

Qualitative research findings to date suggest that the process of claiming benefits in the UK can be psychologically distressing (De Wolfe, Reference De Wolfe2012). A large-scale longitudinal study in England explored the impact of a reassessment programme introduced for certain benefits, and found that it was associated with an increase in both reported mental health problems and suicides (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Taylor-Robinson, Stuckler, Loopstra, Reeves and Whitehead2016). Participants in the study by Garthwaite (Reference Garthwaite2014) described debilitating anticipatory anxiety about any contact from the DWP: a continuous ‘fear of the brown envelope’. In a study exploring the experiences of people with an acquired brain injury and their caregivers claiming DLA, the initial application process was criticised as problematic and actively depressing due to the focus on an illness model and limitations, putting people in the position of being dependent and feeling like a burden (Gillespie and Moore, Reference Gillespie and Moore2016).

The process of claiming benefits has been reported as particularly insensitive to the needs of those with mental health difficulties (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Pinfold, Cotney, Couperthwaite, Matthews, Barret and Henderson2016). A participatory social welfare study found that claiming benefits for mental health-related difficulties was humiliating, isolating and frightening, creating a sense of powerlessness (Ploetner et al., Reference Ploetner, Telford, Brækkan, Mullen, Turnbull, Gumley and Allan2019). This appears to be magnified for people who have experienced prior psychological trauma: i.e. exposure, often repeatedly, to highly aversive and threatening experiences, with subsequent enduring and distressing emotional, cognitive and physiological responses. People experiencing post-traumatic difficulties, including but not limited to a formal diagnosis of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), can be re-traumatised when exposed to events that mirror prior trauma, especially any sense of threat to personal safety or security. At such times they experience extreme distress, sometimes fearing for their lives. A large-scale study of military veterans’ experiences of the UK benefits system found that, because of a lack of understanding of the impact of trauma, participants had been treated in ways that were disrespectful and disempowering, and in some cases re-traumatising (Scullion and Curchin, Reference Scullion and Curchin2022). Appealing against the removal of benefits has also been described as re-traumatising, as people felt mistrusted and were asked to describe distressing prior experiences without emotional support (Shefer et al., Reference Shefer, Henderson, Frost-Gaskin and Pacitti2016). Beyond formal research, the personal experiences of people with a diagnosis of PTSD attending PIP assessments have been described as highly distressing and panic-inducing (Ryan, Reference Ryan2016), with assessors lacking empathy and not demonstrating a trauma-informed approach (Hutchinson, Reference Hutchinson2018).

There is increased recognition that systems can serve to harm and re-traumatise individuals who have a history of psychological trauma – for example, by restrictive practice, coercion, withholding information and inadvertently triggering the re-enactment of early traumatic experiences (O’Hagan et al., Reference O’Hagan, Divis and Long2008). This has led to calls for public services to acknowledge the social and psychological factors in the development and maintenance of distress (Dillon et al., Reference Dillon, Johnstone, Longden, Speed, Moncrieff and Rapley2014), and to develop more informed approaches that acknowledge the impact of trauma and resist re-traumatisation (Hodas, Reference Hodas2006). The concept of Trauma Informed Care (TIC) was developed in recognition of the prevalence of trauma, and the need for service providers to understand this in order to provide appropriate support to people in multiple contexts (Harris and Fallot, Reference Harris and Fallot2001). TIC has relevance to an array of services including medical care, mental health, education, criminal justice, and social care. Importantly, trauma-informed services are not designed to treat symptoms related to trauma; rather, they are services where staff are aware of, and sensitive to, the importance of considerate and compassionate relationships with individuals in any context (Jennings, Reference Jennings2004). In Scotland, the public body NHS Education for Scotland (NES) provides education and training to healthcare staff and broader public services. In 2016, the Scottish Government commissioned NES to develop the project that became Transforming Psychological Trauma: A Knowledge and Skills Framework for the Scottish Workforce, as part of a wider plan to develop a national trauma training strategy for the whole country. The framework has four tiers: trauma informed, trauma skilled, trauma enhanced, and trauma specialist. The first tier, trauma informed, proposes knowledge and skills that should be required by everyone in the Scottish workforce, regardless of role. The framework is based on existing TIC literature and further informed by people with lived experience, with five key principles of trauma-informed working identified: safety, trust, collaboration, choice, and empowerment (NES, 2017, 2019).

While the pioneering study by Scullion and Curchin (Reference Scullion and Curchin2022) focused on veterans, there has been no research to date into how TIC principles are being implemented in the UK benefits system as accessed by a general adult population. The present study therefore aimed to explore the experiences of applying for a specific UK benefit, PIP, from the perspective of people who had experienced historical trauma including abuse, neglect, and pervasive threat from others. At the time the study was conducted, the entire benefits system in Scotland was in the early stages of devolution from the UK Government to the Scottish Government, involving a comprehensive redesign of processes in which PIP is to be replaced by a new Adult Disability Payment (Scottish Government, 2019, 2021). It was therefore hoped that the research might provide insight into how a trauma-informed approach might be applied in this new Scottish system, as well as the existing UK one. Additionally, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, more people have been accessing the benefits system for the first time, with unprecedented levels of new claims reported (DWP, 2022b). Research into individuals’ experiences is therefore timely in ensuring assessments accurately capture claimants’ needs.

Aims

The primary aim of the study was to understand to what extent, based on participants’ experiences, the process of PIP assessment fits the principles of TIC, utilising the framework by NES (2019). There were two secondary aims: to identify salient experiences that were not captured by the TIC framework, and to establish the limitations of the framework for understanding participants’ experiences.

Method

This was a qualitative study in which data were gathered using semi-structured interviews and interpreted using seven-stage framework analysis (Gale et al., Reference Gale, Heath, Cameron, Rashid and Redwood2013). Inductive thematic analysis was used with data that were not captured within the framework (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Participants were 12 adults (four male, eight female) who were accessing psychological therapy for post-traumatic difficulties, including but not limited to cognitive intrusions, flashbacks, emotional distress, hypervigilance, and difficulties with trust. Each had been assessed for PIP in the preceding three years. Their ages ranged from 20 to 62. They were recruited from community mental health services in two Scottish health boards, NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde (NHSGGC) and NHS Lanarkshire, and were provided with plain-English information about the study prior to making a choice about whether to participate. Ethical approval was obtained from the NHS West of Scotland Research Ethics Committee 4 (ref: 20/WS/0161), and the study was approved by the Clinical Research and Innovation/Development departments in NHSGGC and NHS Lanarkshire. Care was taken to ensure that the study itself was conducted in line with the principles of TIC. The epistemological position of the study was critical realism, i.e. an attempt to understand participants’ experiences while recognising the influence of the broader social and political context, and of the researchers’ own experiences, perspectives and values (Danermark et al., Reference Danermark, Ekström and Karlsson2002).

Because of the Covid-19 pandemic, interviews were conducted by telephone or by NHS-approved videoconferencing software. They were carried out by the first author, a trainee clinical psychologist at the time, and ranged from 35 to 90 minutes in length (mean 50 minutes). Interviews were recorded using an encrypted audio device, and each participant was assigned a pseudonym to ensure confidentiality. Framework analysis was conducted as outlined by Gale et al. (Reference Gale, Heath, Cameron, Rashid and Redwood2013), including use of researchers’ field and reflective notes, plus regular supervision. The TIC framework used in the analysis was based on the policy document The Scottish Psychological Trauma Training Plan (NES, 2019), which in turn was informed by the wider evidence base for trauma-informed organisations and approaches, particularly Harris and Fallot (Reference Harris and Fallot2001). There are five principles at the centre of the NES (2019) model: safety, trust, collaboration, choice, and empowerment. Subsequent thematic analysis, leading to the development of an extended, dyadic framework, was explored, discussed and agreed by all authors. NVivo software was utilised to facilitate data analysis (QSR, 2020). Rigour of the analytical process was ensured by use of the COREQ checklist (Tong et al., Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig2007).

Results

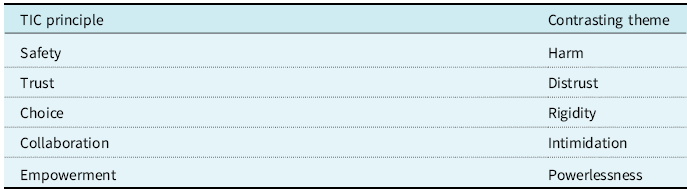

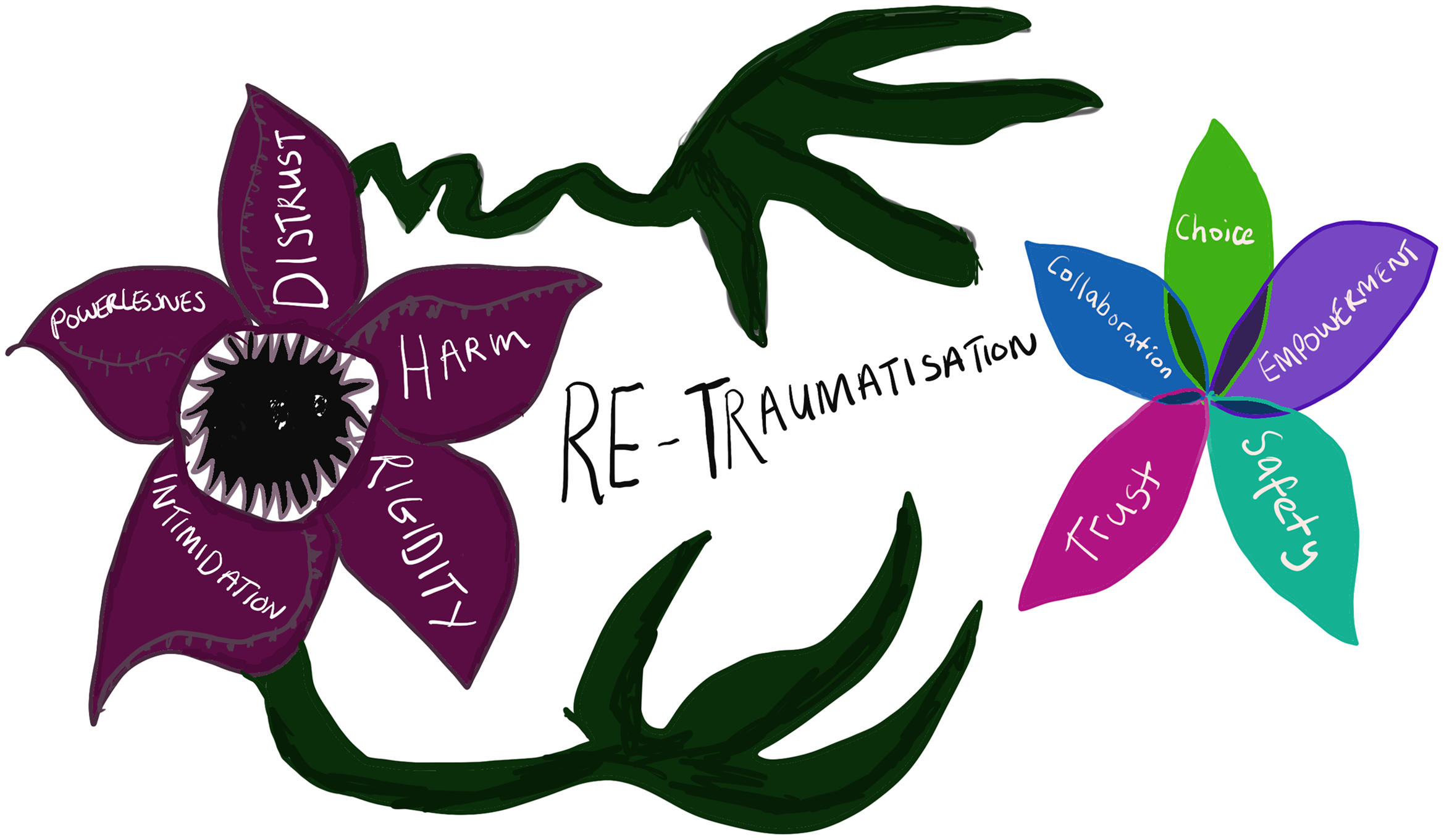

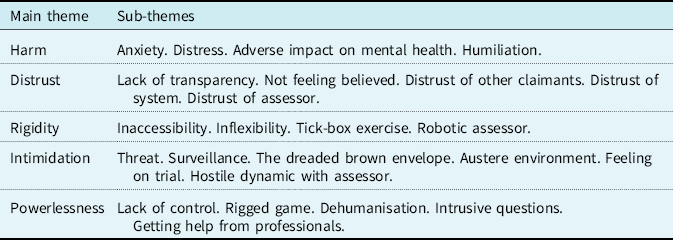

The overarching theme of responses was re-traumatisation. Participants reported finding the PIP assessment process distressing, and sometimes reminiscent of historical experiences of abuse. A loss of power, control and safety further replicated the dynamics of prior trauma. While this was in direct contrast to the principles of TIC, the framework nevertheless allowed for participants’ experiences to be captured if it was extended dyadically using contrasting themes induced from the qualitative data via thematic analysis. This expanded framework is depicted in Table 1. The alternative framework could be conceptualised as being ‘trauma blind’ (Quadara and Hunter, Reference Quadara and Hunter2016). Figure 1 is a graphical representation of the two frameworks. The inductively coded sub-themes that informed the main themes are shown in Table 2. These themes might be considered as fluid and interlinked, with each impacting on the others. Each main theme and sub-theme is considered in more detail below.

Table 1. TIC principles and the dyadically contrasting themes from participants’ data

Figure 1. The induced Trauma Blind framework contrasted with the original Trauma Informed Care framework.

Table 2. Main themes and sub-themes from participants’ data

Harm

Participants described how engaging with the benefits system was harmful to their mental health, exacerbating feelings of anxiety, worry, and stress.

Anxiety

All participants conveyed how anxiety-provoking they found the PIP assessment process. From filling in the paperwork to attending the assessment to waiting for the outcome, the uncertainty and worry coloured their lives, making it difficult to see beyond it. A palpable sense of immobility was described; of participants not being able to move forwards in life while entangled in the PIP process.

It just hangs over you – it’s like you can never really focus on your mental health and look towards the future. (Christine)

Distress

Ten participants reported finding the assessment distressing, describing how they became tearful, overwhelmed and confused during it. Ross stated that he would ‘rather go to prison, or get another cancer operation’ than attend another assessment. Some participants talked about finding the assessment so upsetting and re-traumatising that they experienced suicidal thoughts afterwards.

There was a possibility I might have done something stupid, and I have not felt that way in years. That’s how bad he made me feel, and that seems ridiculous. That that is literally how bad he made me feel, he made me feel so worthless. And I dread going through this again, I hate it, absolutely hate it. (Susan)

Two participants said they actively attempted to end their lives following assessment.

Adverse impact on mental health

Participants described the process as detrimental to their mental health, impacting them beyond the assessment itself due to the uncertainty of the outcome. Jack described the impact of being in the assessment system as such that ‘in a way it almost stifles any chance of your recovery’, while Emma expressed the continued exhaustion she felt after attending assessment:

I mean, the times I’ve been for these assessments, I’ve come out and spent the next three or four days in a stupor, and that’s God’s truth, it’s a horrible experience.

Humiliation

A strong theme of humiliation was evident. Ross described the process as resulting in a situation where he ‘felt like a beggar’, something further exemplified by Jack: ‘It’s an absolute assault on your dignity’. A complex interplay of factors created a sense of shame and humiliation, including the personal questions participants had been asked about toileting, the unpleasant physical environment, and interactions with staff.

I was really going through a bad time and I really didn’t want to be amongst a lot of people – you know how, when you sit in the waiting room – so they had sat me in a chair in a corridor. I found it quite humiliating as there were no chairs, it was just let’s drag this chair and I’ll sit on it. I remember this girl, woman, came up to me; she came right up close to my face and spoke to me as if I had a hearing problem. You know, it was that slow kind of ‘are … you … OK’ and I felt really, felt humiliated. (Emma)

Distrust

Distrust was a prominent theme throughout all interviews: of the assessment process, of assessors and of the wider system, along with participants feeling they were treated with scepticism and not believed. There was also a sense of suspicion towards other claimants.

Lack of transparency

The assessment and decision-making process felt cryptic and confusing. Assessment questions were perceived as unclear, with several participants stating that the same questions were worded in different ways throughout. Participants conveyed a sense of confusion as to what they would need to provide to be considered eligible for PIP.

You have no way of knowing how they are assessing what you’re saying and recording it. You’re asked to sign a form, but you don’t know what you’re signing. It’s not clear what information they require from you to prove your claim. They don’t tell you what they need, they just expect that you’re going to automatically understand and know what that is. (Lucy)

Not feeling believed

Ten participants expressed how the assessment appeared to demand some kind of material proof of their mental health difficulties. Differences between physical and mental health were highlighted, and how the PIP assessment was geared towards the former. Participants conveyed how their mental health experiences were not identified or understood, leaving them feeling like they were not believed; indeed, five stated explicitly that they did not think their assessor believed them. If PIP was not awarded, this reinforced the sense of being disbelieved and invalidated – something which echoed previous traumatic and post-traumatic experiences.

It’s so belittling, because basically they don’t believe you. And it’s just, it makes you so, it makes you so upset, but angry at the same time, because it’s like, when you get, when it comes back and you have zero points, you’re like, they clearly didn’t believe a word I said, because if they did, they would have at least given me some, but they gave me nothing. And so obviously, you know, they have to think I’m lying. And that’s just, I just think, what do you need me to do? (Susan)

Mariah described the negative impact on her mental health of disclosing past self-harm and suicide attempts to her assessor, and this not being reflected in their report or the assessment outcome:

It makes me feel a lot worse, because it makes me feel as if they don’t believe me. I’ve told her all this and it’s like it goes in one ear and out the other. It’s like you go that deep to somebody, to tell them about your struggles. And it’s like they just shut it away to the side.

Six participants described an incongruence between how highly distressed they were feeling during the assessment and the assessor’s subsequent report, which did not acknowledge this. It may be that certain nuances of distress went unnoticed, particularly trauma responses such as dissociation and appeasement, which an untrained assessor might easily miss.

Distrust of other claimants

Three participants expressed the view that other benefits claimants were not being honest. Katie in particular gave the impression that narratives in the media had influenced her perception of other claimants as either deserving or undeserving. At the same time, participants expressed concern that they themselves would be seen by others as disingenuous, in turn meaning they felt they had to try even harder to convey their own honesty and deservingness of PIP. This can be seen to overlap with the complexity of needing to prove mental health struggles.

Distrust of system

Distrust of the DWP and the entire benefits system was expressed by all 12 participants. The system was described as malevolent and duplicitous, with Jack stating: ‘It wasn’t there to help me, it was there to catch me out’ and Ross saying the assessment process was set up to ‘trick’ people. Tara said that she felt the system was not about trying to help claimants but was instead about ‘saving as much money as they can for the government’. The frequency of appeals and re-assessments reinforced participants’ lack of trust, and the pervasive sense of mutual suspicion maintained anxiety and distress.

I feel as if when you go, you’ll either get nothing or less than what you’ve got. They’re reducing the help they give you every time you go. (Katie)

Distrust of assessor

Ten participants described not trusting the individual person who assessed them. While this was reflective of participants’ more general distrust of the system, many reported discrepancies between what they had said and what was written in their report. Susan articulated what she perceived as a double standard between the honesty required from claimants and what was required from assessors:

You’ve got the date wrong and they’ll say you lied. But they can blatantly lie – not mistakenly, blatantly lie – and get away with it.

Rigidity

This theme, with its four sub-themes, was induced from a variety of different descriptions by participants, each of which suggested a sense of the assessment process – and sometimes the assessors themselves – being unaccommodating and impersonal.

Inaccessibility

Participants with additional physical health problems stated that the buildings in which their assessments took place did not meet their needs. Not only did this add to emotional stress; it could lead to physical pain.

And I was asked to go upstairs as well. I said, do I need to go upstairs, really? She goes: ‘There’s a lift there.’ And I thought, even walking to the lift there, walking to where it was, I was in agony and practically holding on to the wall. (Katie)

Inflexibility

A marked lack of choice was reported by seven participants. They felt they had no choice as to the date, time and location of the assessment, even if it was very inconvenient. Two participants said that, due to their trauma history, they wanted to choose whether they had a male or female assessor, but this was not an option.

I feel like maybe we should be given the choice – these are the days I can do, these are the times I can do. You know, it may not be possible, but it’s just something that I feel like would be better for quite a lot of people. (Tara)

Tick-box exercise

Susan used the specific phrase ‘tick box’, which encapsulates this theme of impersonality. Participants did not feel as if the assessor was engaging with them as a human being, and the impression was of a script that might as well be facilitated by a computer, with a requirement to answer set questions in a particular way.

It feels like you’d be better sitting there answering questions and pressing buttons. (Katie)

You just feel like they are putting data into the system and you’re just relaying it to them or something – it’s not like an actual person, you know. (Jean)

Robotic assessor

Relatedly, assessors were described by the majority of participants as displaying a detached and ‘robotic’ stance (Tom’s specific word). For some participants this was apparent in assessors’ body language, including a lack of eye contact.

The woman hadn’t even looked at me, she was just sitting there typing. It did just feel very impersonal. When you’re talking to someone and they’re not even looking at you, it’s not nice at all. (Jean)

Seven participants stated that their assessor lacked empathy. Ross experienced a panic attack during a telephone assessment but explained: ‘They never asked once if you were OK or anything.’ Lucy said that she had become overwhelmed and tearful during her assessment but that the assessor ‘kept ploughing on’. Generally, participants’ responses indicated a perceived lack of sensitivity to their feelings, and a sense that interviewers were focused on completing the assessment regardless of the distress it might be causing. However, it should be noted that two participants described more positive experiences, in which their assessor appeared empathic and attuned to how they might be feeling. Both said that this helped ameliorate anxiety during their assessment.

Intimidation

Participants described a sense of being discomfited and even threatened by the DWP generally, and in some instances by their assessor specifically. The physical environment and processes of the system reinforced a sense of continual intimidation.

Threat

Heightened threat responses are a key post-traumatic symptom, and participants reported a pervasive sense of threat in multiple contexts related to PIP assessment, especially waiting for a letter, a phone call, or a re-assessment. Even when an outcome had been decided, there was the sense that threat continued to lurk in the background:

I’m just waiting. I’m waiting for the next letter to turn up. It’s the Sword of Damocles. Just hangs there and hangs there and you never know whether it’s going to fall on you. (Jack)

This sense of threat was also palpable in early experiences during the research. When discussing the study and deciding whether or not to take part, several people expressed concern that the lead researcher was in some way linked to the DWP; that what they said would be reported back to the DWP; and that they would face punishing consequences.

Surveillance

Linked to this overarching sense of threat, several participants recalled feeling as if they were being watched and judged when they were in a building both before and during their assessment: what Tara described as being ‘under the microscope’. This added to a pervasive feeling of disconcertedness and expectation that they might be punished for some unwitting infraction.

The dreaded brown envelope

Unwittingly echoing the title of the paper by Garthwaite (Reference Garthwaite2014), Tom summarised participants’ fears and anxieties about the system more generally with the phrase ‘the dreaded brown envelope’, and Jon described how the arrival of any brown envelope at his home could cause him to ‘freak out’. This theme of anticipatory anxiety was widely endorsed.

It’s just anxiety in my stomach constantly. Even, see when the letters come in the morning from the postman, my heart literally starts beating and I know if it’s a normal letter I’m fine, but if it’s a brown letter my anxiety keeps going. (Christine)

The cumulative effect of every day of the week worrying about the post tires you out for all other tasks. (Jack)

Austere environment

The physical environment where the assessment took place was described as ‘anxiety-provoking’ (Jon) and ‘absolutely awful and disgusting’ (Susan). Participants conveyed how sitting in an austere, unfriendly waiting room, with other anxious claimants, exacerbated their own already-high levels of anxiety and threat.

It is a powder-keg of a situation. It really is, and the amount of time that you’re left alone together in that one room, you can feel it. You know, and that makes yours even worse. It is just a room full of anxiety. Just feeding more anxiety. (Tom)

Feeling on trial

As already noted (see the theme of Distrust, above), almost all participants described feeling obliged to provide some kind of material proof of intangible mental health difficulties. Relating to the present main theme of Intimidation, four participants used the metaphor of being on trial in a court, highlighting how it felt as if they had done something wrong and had to prove themselves innocent. Christine and Emma respectively described how fearful they felt being ‘cross-examined’ and ‘interrogated and accused’ by an assessor.

Hostile dynamic with assessor

Ten participants expressed feeling uncomfortable with the person who did their assessment. They described sternness, a lack of empathy, non-verbal cues that signified irritation, and feeling like they had not been heard. Participants described the power imbalance between themselves and their assessor, which in some cases precipitated unwelcome memories of previous coercive experiences.

You’re in this vulnerable spot sitting in this chair with – I’m making it terrible, but it is, it’s like Attila the Hun sitting there, and again it’s a person in control, almost of your feelings as well. (Christine)

Powerlessness

This final main theme was derived from participants’ responses highlighting a lack of control, agency and autonomy. Participants felt that they did not have a voice that anyone would listen to, and conveyed a feeling of being ‘done to’ rather than worked with.

Lack of control

Ten participants talked about feeling they had little control during the assessment process, and little influence over the outcome. Some stated that this was exacerbated by the stressful nature of the assessment and their heightened anxiety. Tom stated specifically how daunting it was to be in front of ‘a stranger who decides what happens in your life. I find that quite scary’.

Rigged game

This sub-theme overlaps with Distrust, above, but more explicitly articulates the perceived unfairness of the process and participants’ vulnerability. It was Jack who used the phrase ‘rigged game’, elaborating:

This whole system is like playing a game of snakes and ladders where every single snake goes back to zero. And there are very few ladders.

Lucy’s summary of the injustice and unfairness she perceived was succinct:

It’s not a level playing field. I don’t think it’s meant to be a level playing field.

Dehumanisation

The concept of the assessment being dehumanising was poignantly expressed in a number of ways, including the environment, the questions that were asked, and the manner of the assessor. Emma stated that, during assessment, she ‘didn’t really feel like a person’ – an unambiguous statement of the impact upon her sense of self. Katie described feeling ‘like just another number’, while Jean went further, explaining that when she arrived for her assessment appointment she was given a number, and that she was then called into the room by way of that number, not her name: ‘It made you feel so small.’

Intrusive questions

Powerlessness was also palpable in the way participants discussed the questions they were asked at assessment. Many perceived these as intrusive, especially when they were being asked about aspects of personal care and hygiene. It is notable that, during the research interviews, some participants struggled to find words when trying to talk about their feelings about these questions, conveying a sense of shame as they recounted their experiences. Eight participants spoke about feeling they had no choice but to disclose extremely personal information to their assessor, even though they were deeply uncomfortable doing so, and there was no pre-existing relationship or mutual trust established.

Getting help from professionals

Three participants spoke about how it was helpful to get letters of support from their psychologist, and that they found this empowering by proxy. Jack explained: ‘With him having the Dr before his name, it cuts so much ice with the DWP.’ This, however, implies that the DWP consider professionals’ views to be more valid than claimants’, and one participant explained that they had in fact found this disempowering:

It’s the fact that I’ve got to get my psychologist to give proof, it’s quite crap – like I’ve got to get evidence from a higher-up person. (Mariah)

Discussion

The primary aim of this research was to understand to what extent participants’ experiences of PIP assessment fitted the principles of TIC (NES, 2019). Secondary aims were to identify key experiences that were not captured by the TIC framework, and by extension to establish the limitations of the TIC framework for understanding these. As the results make clear, people’s experiences did not fit TIC principles, and indeed contrasted them so powerfully that an alternative framework was required. Nevertheless, considering the secondary aim, this alternative could still be based on the original TIC framework. Our derived main themes can be conceptualised as being in dyadic contrast to the TIC constructs: harm, not safety; distrust, not trust; rigidity, not choice; intimidation, not empowerment; and powerlessness, not collaboration. Rather than being trauma informed, we posit that this alternative framework is trauma blind (Quadara and Hunter, Reference Quadara and Hunter2016). Bluntly, a lack of awareness and understanding of trauma by the UK DWP risks re-traumatising people who deal with the organisation. The concept of trauma blindness was highlighted by Scullion and Curchin (Reference Scullion and Curchin2022) in their examination of veterans’ experiences, and our proposed framework expands upon this. If TIC can be more clearly understood from a dyadic or continuum-based perspective, this may enable organisations to identify their trauma-blind behaviours, to address these, and perhaps to evidence their progress toward becoming increasingly trauma informed. This is considered further in the Implications sub-section, below.

In line with other research (e.g. Ploetner et al., Reference Ploetner, Telford, Brækkan, Mullen, Turnbull, Gumley and Allan2019; Pybus et al., Reference Pybus, Pickett, Lloyd, Prady and Wilkinson2021), our findings indicate that mental health difficulties in general are not necessarily recognised in DWP benefits assessments. This lack of recognition is experienced by claimants as invalidating, and can be re-traumatising. It is notable that, for some participants in the present study, attending a research interview appeared to evoke feelings that they had experienced during PIP assessment, and the interviewer was acutely aware of people’s perceived need to prove the validity of their experiences, and to be believed. Trust and safety are fundamental concepts of TIC, yet participants described a pervasive lack of these. It is plausible that this will in turn perpetuate negative dynamics in all interactions between claimants and the broader benefits system (Bloom, Reference Bloom and Tehrani2011), and indeed that working in such a system could have a deleterious impact on DWP staff, who may experience conflict between their perceived professional duties and their personal values. This in turn could result in othering and reduced empathy, as a way of attempting to reduce this dissonance (Sweeney et al., Reference Sweeney, Clement, Filson and Kennedy2016). Again, this is considered further in the Implications, below.

Strengths and limitations of the present study

A stated aim of this research was to establish the limitations of the TIC framework for understanding participants’ experiences. Per Harris and Fallot (Reference Harris and Fallot2001), the NES (2019) TIC framework that was utilised highlights important principles that underpin trauma-informed approaches. However, it does not capture the dynamic nature of these principles, and we would argue that there is a complex inter-relationship between the different aspects of the TIC framework, and that these are best understood together and not as individual parts. This made using framework analysis challenging, and it was important to balance the TIC principles with the flexible deduction and development of an alternative framework, ensuring that this captured the salient themes in the data and that participants’ experiences were not overshadowed by an a priori model.

The research provides insight into the lived experiences of 12 individuals, and we believe that it makes an important contribution in terms of both research and future policy directions, foregrounding the experiences of people who have been all too frequently unheard. While it is not possible simply to generalise from this sample to any wider population, the results echo existing findings and suggest an increasing stability of themes across related research – namely, disempowerment, threat and re-traumatisation (Levitt, Reference Levitt2021). While framework analysis provided a rigorous and transparent method of conducting this qualitative research, a phenomenologically oriented approach may provide further perspectives and insights, and this suggests a fruitful avenue for further exploration.

Due to time constraints, it was not possible to give participants the choice of reading through and commenting on their transcripts. Such respondent validation has been used to promote research trustworthiness; however, it has also been criticised for being time-consuming and potentially distressing for participants, particularly if their transcript is of an emotive nature (Birt et al., Reference Birt, Scott, Cavers, Campbell and Walter2016). The lead researcher used supervision and regular discussion with co-authors to explore plausible alternative constructions, and to challenge assumptions.

Clinical, research and policy implications

Most research into the implementation of TIC has been in North America, but there are some examples of successful implementation within the UK (Wilton and Williams, Reference Wilton and Williams2019). In the North of England, the Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust implemented a programme to develop trauma-informed services, with key facilitators being the appointment of trauma champions, appropriate supervision, and follow-up training plans. Studies elsewhere have likewise emphasised the need for strong leadership, commitment to long-term training, the recognition of vicarious trauma in staff, and the need for supervision from experts in trauma such as applied psychologists, including outwith healthcare settings (Chandler, Reference Chandler2008; Drabble et al., Reference Drabble, Jones and Brown2013). The rollout by NES of the national trauma training programme in Scotland is therefore welcome and pertinent, a core aim being that all services should at least be trauma aware. The significant changes being made to the benefits system in Scotland provide a unique opportunity for trauma-informed service design and delivery. Our findings underline the importance of appropriate training being implemented across benefits systems: however, at the same time we recognise that staff simply attending courses will not be enough to bring about meaningful change. There also needs to be a top-down commitment to ensuring that the principles of TIC are truly embedded in organisations such as the developing Social Security Scotland, including consideration of the wellbeing of staff. Without this, there is the risk that TIC could appear tokenistic and insincere, as has arguably happened when the recovery movement has been co-opted by services (McWade, Reference McWade2016; Stuart et al., Reference Stuart, Tansey and Quayle2017).

As it can take decades for policies to be incorporated into routine practice, clinical or otherwise (Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, Landsverk, Aarons, Chambers, Glisson and Mittman2009), immediate support for such development is crucial. Implementation science has an important role in assisting organisations such as benefits agencies to take steps to become truly trauma-informed (Damschroder et al., Reference Damschroder, Aron, Keith, Kirsh, Alexander and Lowery2009). Steps such as those outlined above – the appointment of trauma champions, appropriate supervision, and a commitment to training plans – would usefully be augmented by a complete, service-wide consideration of organisational culture and potential barriers to change; regular and transparent service evaluation; and a rewards and recognition scheme for staff (Tansella and Thornicroft, Reference Tansella and Thornicroft2009). While this would necessitate a commitment in terms of time and resources, it would go a considerable way toward addressing the issues highlighted by the present research, and arguably contribute to the improved health of a nation (NHS Health Scotland, 2016).

Ongoing research into the timing of benefits assessments, and subsequent physical and mental health outcomes, is also recommended, to further understand the potential impact. In Scotland, the existing national data-science infrastructure offers potential for large-scale data-linkage studies, conducted ethically via the special NHS board Public Health Scotland. At the same time, research exploring the perspectives of those working with and for the benefits system would provide important insights. The present results suggested a lack of empathy and responsiveness from assessors, and it is important to understand the reasons for this. Such exploration is particularly important given the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, which has put more pressure upon all public systems, with concomitant risk of staff burnout (Aughterson et al., Reference Aughterson, McKinlay, Fancourt and Burton2021; May et al., Reference May, Aughterson, Fancourt and Burton2021).

Finally, given that this study highlights how distressing PIP assessments can be for those who are already receiving therapy for post-traumatic distress, it is incumbent upon mental health clinicians – and, perhaps more pertinently, the organisations employing them – to recognise this. Institutional support for clinicians to assist patients (for example, by writing letters of support to benefits agencies) would be of considerable benefit (Cantrell et al., Reference Cantrell, Weatherhead and Higson2021).

Conclusion

PIP assessments were found to be re-traumatising and to have an adverse impact on claimants’ mental health, a finding in line with prior research into the benefits system. Participants’ experiences contrasted the principles of TIC to the extent that an alternative framework was created, with five overarching themes: harm, distrust, rigidity, intimidation, and powerlessness. Rather than being trauma informed, at present the PIP assessment process would more accurately be described as trauma blind.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.