Introduction

Canada's party system is anomalous. According to Duverger's Law, strongly majoritarian electoral contexts such as Canada's single-member-plurality electoral system are expected to produce party systems characterized by a competition between two major parties, like the Democrats and Republicans south of the Canadian border (Duverger, Reference Duverger1959; Sartori, Reference Sartori, Palombara and Weiner1966). Bucking the trend, Canada is a multiparty system dominated by a party of the centre. Richard Johnston (Reference Johnston2017) describes Canada's party system as a case of “polarized pluralism,” which refers to the ability of the centrist Liberal Party to monopolize the centre of two axes dividing Canadians’ electoral preferences: one is the left/right ideological dimension defining electoral preferences in most political contexts; the other is what Johnston (Reference Johnston2017) refers to as a “national dimension,” born of the question of Quebec's role within Canada. Johnston (Reference Johnston2017: 5) notes that this kind of “second dimension with identity politics content” is not unusual, but he contends that the Liberal Party's ability to hold the middle on both axes is.

While Johnston's analytic history offers important insights into the nature of the Canadian party system, certain shortcomings limit its explanatory potential. For one, although Johnston discusses ethnolinguistic and religious identities, he has little to say about other social identities or the dynamics of intergroup processes more generally. As the author admits, “The book has little to say about New Canadians (except as part of a highly aggregated ancestry category), First Nations, the north, gender, or sexuality...Quebec aside, the identity politics in this book are also mostly dated” (Johnston, Reference Johnston2017: 261). Second, Johnston's analysis tends to take the political party (or election) as the unit of analysis. And while this allows the author to offer a sweeping analysis of the long history of Canada's party system, it faces the same shortcoming plaguing the neo-Duvergian theories. Specifically, that although studying electoral outcomes allows one to conclude that voters must be responding in predictable ways to different contexts, party- or election-level analyses tell us little about what is going on in the hearts of the citizens casting ballots. These analyses give little insight into what motivates citizens to vote at all, and they “[beg] the question of why voters would care given their individual impotence” (Johnston, Reference Johnston2017: 261).

In the first section, we expand the theoretical framework for understanding the Canadian party system by linking the party systems literature to the burgeoning literature on social identity theory. Social identity theory developed out of the finding that categorizing people into groups, even arbitrary (or minimal), elicits strong cognitive and behavioural outcomes (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1970, Reference Tajfel1974; Brown, Reference Brown2000). Drawing on social identity theory we should expect that any salient social group—including national, ethnic, sexuality, and political groups—can shape social judgments and impact political behaviour. Our analysis takes seriously the contention that although social and political categories are fuzzy, voters’ feelings toward groups cluster together in meaningful ways to systematically impact voters’ behaviour (Cochrane, Reference Cochrane2015). Our goal is to understand how social cognition—specifically, voters’ relatively warmer or colder feelings toward different social groups—impacts vote choice, offering a more direct look at the individual-level motivations that shape voter behaviour and, ultimately, animate the dynamics of the party system.

In the second section, we outline our methodology. We used public opinion data collected by the Canadian Election Study (CES) that included measures of voters’ relatively warmer or colder feelings toward different social groups and vote intentions. Using all of the available data at our disposal, we analyzed data from seven elections (1993, 1997, 2006, 2008, 2011, 2015, 2019) spanning over a quarter of a century and included variables measuring feelings toward 12 different social groups. This includes voters’ feelings toward political groups (the Liberal, Conservative, Reform, Bloc Québécois, and New Democratic parties), nations (Canada, Quebec and the United States) and other social groups (racial minorities, Indigenous peoples, sexual minorities, and feminists). Because including such a high number of highly correlated variables would pose a problem for estimating vote choice using regression, we use an unsupervised machine learning technique, principal component analysis (PCA), to preprocess the data and reduce the dimensionality of affective space.

We present our results in the third section. In this section, we show how Canadian voters’ feelings toward different groups are associated with vote choice over time. Offering evidence for one of the central tenets of the theory of polarized pluralism, we show that having warm feelings toward pro-Quebec groups is associated with voting for the Liberal Party outside Quebec but not in Quebec, where the Conservative Party and the Bloc Québécois have been competing for the nationalist vote. We also present evidence of growing affective distance in Canada between left-wing parties’ supporters and right-wing parties’ supporters. With respect to Canada outside of Quebec, we find that having warmer feelings toward groups associated with the Right (relative to groups associated with the Left) has become a notably stronger predictor of voting for the centre-right Conservative Party relative to the centre-left Liberal Party over time. By the same token, ideological affect no longer predicts voting for Canada's social-democratic New Democratic Party (NDP) relative to the Liberals, pulling the party system away from polarized pluralism. Our results suggest that the distinction between the previously more clearly left-leaning NDP and the centre-left Liberal Party is fading away, restructuring competition along the ideological dimension in terms of a competition between the Left (either of the left-leaning parties) and the Right (the Conservative Party). We then discuss our results. We conclude by offering suggestions for future research and present our commentary on the future of Canada's electoral politics and party system. We expect the Canadian party system to move away from polarized pluralism by bisecting further along the left/right ideological divide.

Social Identities and Polarized Pluralism in Canada

There is a long-standing interest in the relationship between political behaviour and social identities (Berelson et al., Reference Berelson, Lazarsfeld and McPhee1954; Johnston, Reference Johnston1985, Reference Johnston and Wearing1991; Blais, Reference Blais2005) or processes of social cognition, such as categorization (Cochrane, Reference Cochrane2015). Increasingly, political scientists are drawing on social identity theory to explain political behaviour (for example, Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019; Pickup et al., Reference Pickup, Kimbrough and de Rooij2021; Groenendyk et al., Reference Groenendyk, Kimbrough and Pickup2022). Social identity theory recognizes that social group memberships play an important role in cognition and behaviour (Tajfel et al., Reference Tajfel, Turner, Hatch and Schultz2004; Huddy, Reference Huddy2001). According to social identity theory, perceptions of group memberships trigger automatic positive evaluations of one's perceived in-group and negative evaluations of perceived out-groups (Billig and Tajfel, Reference Billig and Tajfel1973). Even the most minimal of social categories can elicit strong cognitive and behavioural responses: categorizing people into arbitrary groups—such as their preference for certain paintings—can elicit in-group favouritism and intergroup competition (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1970, Reference Tajfel1974). The finding that categorizing people into arbitrary, or minimal, groups could elicit strong cognitive and behavioural outcomes was formative in the development of social identity theory (Brown, Reference Brown2000).

With respect to social judgments, a series of studies offer strong evidence that people everywhere judge both individuals and social groups based on two universal dimensions: warmth (liking) and competence (respect) (Fiske et al., Reference Fiske, Cuddy and Glick2007; Cuddy et al., Reference Cuddy, Fiske and Glick2008; Fiske, Reference Fiske2018). While warmth and competence together account for the majority of the variation in social perceptions, the dimension related to warmth, or liking, is primary. As Fiske et al. (Reference Fiske, Cuddy and Glick2007) explain, warmth is automatically judged first because people are cognitively more sensitive to information related to warmth, and warmth judgments carry greater weight in terms of behavioural responses. With respect to behavioural outcomes, the warmth dimension predicts active behaviours, with greater perceived warmth increasing active helping and lower perceived warmth increasing active harming.

Growing partisan discord, which is particularly visible in the United States, is fuelling scholarly interest among political scientists in how social identities impact voter behaviour. More specifically, political scientists are increasingly interested in “affective polarization,” which refers to the way political partisans’ increasing dislike for out-group partisans is fuelling political polarization (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019; Kinder and Kalmoe, Reference Kinder and Kalmoe2017). In the United States, affective polarization, operationalized as the tendency for Democratic-identifiers to express dislike for the Republican Party and Republican-identifiers to express dislike for the Democratic Party, has been increasing over time. Efforts to measure affective polarization in Canada have been stymied by the challenge of measuring partisans’ relative dislike for opposing parties in a multiparty system. These methodological challenges have resulted in mixed findings, with some scholars concluding that affective polarization is declining in Canada (Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020) and others concluding that it is on the rise (Boxell et al., Reference Boxell, Gentzkow and Shapiro2020; Johnston, Reference Johnston2019). Another shortcoming of these analyses is that they are limited to the study of party identifiers at the exclusion of independents—centrally important voters who can swing elections.

Finally, existing studies of affective polarization focus exclusively on feelings toward out-group partisans, neglecting feelings toward a range of other social groups. If minimal groups can shape social judgments and behaviour, then surely linguistic, national, ethnic and other salient social groups in Canada can impact social judgments and shape political behaviour. In our analysis, we use feeling thermometer survey items to tap into warmth, or liking—the primary dimension of social cognition—toward a range of social groups, including but not limited to political partisans. The outcome we are interested in is vote choice, an active behaviour that should be influenced by group-based affect.

The importance of social attachments on political behaviour and party system dynamics has not been ignored by Canadian political scientists. The relationship between socio-ideological cleavages and party system dynamics is central to at least two major contributions to the study of Canadian politics: the quantifiable patterns of political disagreement that manifest as a left/right ideological divide in Canada and other democracies around the world (Cochrane, Reference Cochrane2015) and the more distinctly Canadian phenomenon of “polarized pluralism” (Johnston, Reference Johnston2017).

Drawing from social psychology and philosophy, Cochrane's (Reference Cochrane2015) analysis recognizes that cognitive categories are composed of sets of concepts associated based on a relational degree of (dis)similarity and have fuzzy, rather than rigid, boundaries (see also Rosch, Reference Rosch1975; Lakoff, Reference Lakoff2008; Wittgenstein, Reference Wittgenstein2010). Cochrane's (Reference Cochrane2015) research is primarily concerned with the world of political ideas and makes its biggest contribution to the study of how political ideas shape party systems.Footnote 1 Cochrane's (Reference Cochrane2015) analysis shows that similar clusters of ideas are associated with citizens’ left/right self-identification and that over time the distinctions between the parties are increasingly revolving around a left/right divide. Cochrane's work is important for ours insofar as it takes seriously the process by which voters engage in categorization. As we explained, our work is motivated by social identity theory's recognition that categorizing people into groups triggers automatic affective responses, with consequences for social and political action. If social categories have fuzzy boundaries that manifest as family resemblances, we would expect that patterns of group-based affect will as well. Furthermore, drawing on Cochrane (Reference Cochrane2015), we hypothesize that the greatest variation in feelings toward groups in Canada will be summarized along a dimension of left/right ideological affect. We expect to find that the impact of ideological affect on vote choice has been increasing over time.

Our work also draws heavily on Johnston's (Reference Johnston2017) theory of polarized pluralism. Johnston (Reference Johnston2017) describes the post-1970 Canadian party system as a case of polarized pluralism, a multiparty system with a dominant centrist party (Sartori, Reference Sartori, Palombara and Weiner1966). Johnston (Reference Johnston2017) makes the case that the Liberal Party was able to withstand centrifugal forces and occupy the centre on the left/right dimension by taking ownership of the centre on another dimension, the “national question” dimension, which refers to the place of Quebec within the Canadian federation. In the post-1970 period, conflict has revolved around the accommodation of Quebec's claims of nationhood within the federation and Quebec's occasional threats of secession. Quebec's demands have often pushed against the conception of Canada as a multicultural state, ratified in the Constitution Act, 1982. In this context, the Liberals have appealed to two distinct sets of voters. In Canada outside of Quebec, the Liberals have been able to rally voters who support Quebec's demands and francophones’ rights. In Quebec, the Liberals have been able to rally voters who want to live in a multicultural, rather than binational, state. By building a coalition of voters across Quebec and the rest of Canada who are sympathetic to the other side, the Liberal Party has taken hold of the centre. As the champions of national unity, they effectively blocked the growth of the NDP on the left of the ideological dimension and established their dominance within the party system.

However, by occupying the centre on the national question, Johnston (Reference Johnston2017) notes that the Liberals are vulnerable on both flanks. To understand why, it should be noted that, first, Quebec voters tend to vote in unison, and winning over the Quebec voting block has historically been a necessary condition for the Liberals to form federal government (Johnston, Reference Johnston2017; Bakvis and Macpherson, Reference Bakvis and Macpherson1995). The coordination of voters in the seat-rich region of Quebec means that any party that convinces Quebec voters that they are the best defender of Quebec's demands can gain a substantial share of the total seats in federal Parliament. Second, there are many voters who hold pro-Quebec (and anti-multiculturalist) attitudes in Quebec, and many francophobic voters (voters who hold negative attitudes toward Quebec and French-speaking Canadians) in the rest of Canada. The coordination of Quebec voters has allowed the Conservatives, at times, to defeat the Liberals by crafting an ends-against-the-middle coalition that brings together Quebec francophones and francophobic voters in the rest of Canada. Yet, by its nature, this type of coalition is precarious, and the resulting tensions have undermined the Conservatives’ ability to win over Quebec nationalists in the long term. Furthermore, this strategy has often been thwarted by the Bloc Québécois, which, despite being a nationalist party that only runs candidates in Quebec, has been able to win enough seats to carry weight in Canada's federal Parliament because of the coordination of Quebec voters.

The points of friction inherent to polarized pluralism should make it unsustainable. The fact that this system has endured in Canada for decades now is somewhat puzzling. However, signs of its demise have been visible since the 1993 election. Quebec is no longer the pivot for government, due to the region's diminishing demographic weight and the growing fragmentation of its vote, and this is undercutting the base of the Liberals’ dominance (Johnston, Reference Johnston2017). Congruent with Cochrane's finding that the ideological left/right divide is becoming more salient over time in Canada, Johnston (Reference Johnston2017) argues that the centre on the ideological left/right dimension is disappearing, as the NDP has been steadily moving toward the centre, thereby closing the gap with the Liberal Party (Johnston, Reference Johnston2019). On the Conservative Party's side, the emergence of the Bloc Québécois curtailed the reach of their nationalist appeal. Johnston's (Reference Johnston2017) analysis of the Canadian party system stops at this crossroads, a gap that we address with our present analysis.

Methods

To identify how affect shapes vote choice, we proceed in two steps. First, we use PCA to uncover two dimensions of group-based affect, using feeling thermometer data that we interpret as the ideological and ethnocultural dimensions. We then use these two principal components as independent variables in a regression model of vote choice. To do so, we use data collected as part of the CES during the 1993, 1997, 2006, 2008, 2011, 2015 and 2019 Canadian federal elections. Our choice of elections was restricted based on the availability of the data; we included as many elections as we could for which there was the largest set of feeling thermometer variables available to measure group-based affect.Footnote 2 The feeling thermometer variables ask respondents how they feel toward different groups on a 101-point scale, where 0 means they really dislike the group and 100 means they really like the group. Note that we conduct PCA separately for each year and each sample (Quebec and the rest of Canada).Footnote 3

We included all the feeling thermometer rating variables asked consistently across a range of CES surveys in our analysis. Specifically, feelings toward racial minorities, “Aboriginals” (Indigenous peoples), gays and lesbians, feminists, Quebec, Canada, the United States, the federal Liberal Party, the federal Conservative Party, the federal NDP, the Bloc Québécois, the Progressive Conservative Party and the Reform Party. Our goal was to include as many feeling thermometers as possible, but we were limited by the availability of the data. Including feeling thermometer ratings for other theoretically relevant groups, such as toward francophones, anglophones, immigrants and white people, would have strengthened our analysis. However, these feeling thermometer ratings were asked inconsistently, in two or three election surveys. Since our goal is to assess the evolution of the relationship between group-based affect and vote choice across time, we could only include feeling thermometers that were asked repeatedly across elections.

Each feeling thermometer rating was mean-centred at the individual level prior to analysis. Specifically, to help eliminate measurement error (individual-level variation in how people respond to feeling thermometers), we subtracted a respondent's average rating for all feeling thermometers from each feeling thermometer. As such, a given respondent's score on a given feeling thermometer—for instance, the respondent's feelings toward the federal Liberal Party on a 0-to-100-point scale—is relative to that person's feelings toward the other target groups. This addresses the issue that some respondents tend to rate all target groups relatively warmly while others rate all target groups relatively coolly (Wilcox et al., Reference Wilcox, Sigelman and Cook1989; Knight, Reference Knight1984).Footnote 4 This step is essential for identifying the variation we are interested in for our present analysis (a given respondent's truly warmer or cooler feelings toward a given target group, relative to their feelings toward the other social groups under consideration). We then standardized the variables using z-score standardization, which is the convention prior to performing PCA (Hastie et al., Reference Hastie, Tibshirani and Friedman2009).Footnote 5 Standardizing the variables allows us to express the principal component scores in terms of common units of measurement (standard deviations), which facilitates comparisons between the coefficients.

While it is important to know how many different social groups impact vote choice, including a large number of variables makes interpretation difficult. What is worse, including a large number of highly correlated variable (like feeling thermometers) in a regression causes the least squares estimates to be unstable and inflates the standard errors (Fox, Reference Fox1997). PCA is one of the most widely used machine learning techniques for dealing with high-dimensional data. PCA reduces the dimensionality of the data while retaining the important information as uncorrelated variables (Magyar, Reference Magyar2021; Jolliffe, Reference Jolliffe2002; Fox, Reference Fox1997). In political science, PCA has been used effectively as a dimensionality reduction technique to analyze the structure of a party system (Magyar, Reference Magyar2021). Similar techniques have also been used by political scientists to uncover a latent left/right ideological dimension in multidimensional spaces, such as principal factor analysis (Gabel and Huber, Reference Gabel and Huber2000) and network analysis (Cochrane, Reference Cochrane2015). To our knowledge, ours is the first analysis that uses PCA to analyze the underlying structure of an electorate's affective space. Because PCA allows us to reduce the high-dimensional and highly correlated feeling thermometer data to a smaller number of orthogonal features that explain most of the variance in the original data, PCA is known for producing “less noisy” measures (James et al., Reference James, Witten, Hastie and Tibshirani2013: 389). Finally, because PCA is an unsupervised machine learning technique that involves a mathematical transformation of the original data, the results are not dependent upon the decisions of the analysts, a criticism that has been levelled against factor analysis (Cochrane, Reference Cochrane2015: 85) (see section S1 in the Supplementary Material SM for a longer discussion about PCA).

Drawing on Johnston's (Reference Johnston2017) theory of polarized pluralism, we retain two principal components from our PCA, which reflect the two historical axes of electoral competition in Canada: the left/right dimension tapping into ideological affect and a dimension centred around the national question, or ethnocultural affect.Footnote 6 We identified the principal components that represent these dimensions for each sample based on systematic patterns in the feeling thermometer variables’ loadings in terms of direction and magnitude. The loading indicates the covariance between the variable and the principal component. We also made sure that each component is relatively important—that is, it explains at least 10 percent of the total variance (see Tables S1 and S2 in section S1 of the SM). We also conducted a cluster analysis with the feeling thermometer data to confirm that our principal components effectively separate the clusters of observations on these variables.Footnote 7

Recall that PCA is an unsupervised statistical learning technique, and we did not specify the weights for the principal components in advance: the algorithm estimates the components from the underlying data and we interpret the meaning of the components based on the way the variables load onto each principal component. We interpret a principal component as representing ethnocultural affect when the loadings of, on the one hand, feelings toward Quebec and feelings toward the Bloc Québécois, and on the other, feelings toward ethnic minorities and feelings toward “Aboriginal” (or Indigenous) people have different directions and are among the top contributors (see Figure S1 in the SM). The average contribution of these core variables is 36 percent, which means that above a third of their contribution to the PCA is concentrated in the ethnocultural principal component (there are 12 components in total). Hence this dimension is defined by opposing feelings toward groups associated with Quebec and feelings toward ethnic minority groups. To reiterate, we did not make the decision to contrast feelings toward groups associated with Quebec and groups associated with multiculturalism—this opposition was recovered “blindly,” using PCA. However, this is consistent with the substance of the debate on the national question that contrasts Quebec's claim to nationhood and special rights to Pierre Trudeau's multiculturalism, which puts all ethnolinguistic minorities on an equal footing. For our measure of ethnocultural affect, higher scores indicate warmer feelings toward groups associated with Quebec than toward groups associated with multiculturalism, while lower scores indicate warmer feelings toward groups associated with multiculturalism than toward groups associated with Quebec.

We interpret a principal component as representing the “ideological dimension” when the loadings of the variables related to the Right or empowered groups (feelings toward the United States, Canada, the Conservative Party and the Reform Party) and the variables related to the Left or marginalized groups (feelings toward ethnic minorities, feminists, gays and lesbians, Aboriginal people, and the NDP) have different directions and are among the top contributors.Footnote 8 The average contribution of these core variables is 31 percent, which means that about a third of their contribution to the PCA is concentrated in the ideological principal component (there are 12 components in total). Hence this dimension is defined by opposing feelings toward groups associated with the Right (empowered groups—that is, nation-states and right-wing parties) and feelings toward groups associated with the Left (disempowered groups and left-wing parties). Again, this opposition was recovered from the underlying data using PCA; we did not make the decision to contrast feelings toward these groups. However, this opposition is consistent with a standard measure of left/right ideology, the RILE index of the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP), which is used by Johnston (Reference Johnston2017). The RILE index includes variables that relate to power dynamics between social groups such as anti-imperialism, support for the nation-state (“National way of life”), law and order, and traditional morality.

The patterns in the loadings of the variables on the principal component that we identify as the left/right ideological dimension are also consistent with Cochrane's network analysis of the CMP data (Reference Cochrane2015: 72). He finds that additional variables—patriotism, multiculturalism, ethnic minorities and social justice—predict how left-wing and right-wing parties cluster on opposing sides. These patterns relate to the power dynamics reflected in our ideological dimension and how it opposes empowered groups, such as nation-states, to disempowered groups, such as ethnic and sexual minorities. In our analysis, high scores on the ideological dimension indicate warmer feelings for groups associated with the Right and low scores indicate warmer feelings for groups associated with the Left.

We conducted robustness checks to ensure that the principal components that we interpret as ideological affect and ethnocultural affect correlate in meaningful ways with attitudes on relevant issues (see section S3.1 in the SM). Moreover, we replicated the regressions used in the main analysis with alternative measures of our dimensions, namely the traditional left/right scale and the survey item asking “how much should be done for Quebec” that are used by Johnston (Reference Johnston2017) (see section S3.2 of the SM). The results are consistent with those of the main analysis. However, our measures based on PCA are superior for three reasons. First, we contend that social cleavages imply group-based attitudes that transcend policy considerations. Hence survey items that measure policy attitudes are not comprehensive enough. Second, as multi-item indices, our measures more effectively capture the complex nature of the ideological and ethnocultural dimensions. For instance, the national question requires more than just measuring attitudes toward governmental relations between the federal level and Quebec. We need a measure that captures the trade-off between accommodating Quebec's claims and empowering other ethnolinguistic minorities, which is at the heart of the debate on the national question for the period we are interested in. In terms of the left/right scale, research has shown that the interpretation of this concept is highly variable and triggers different associations with other variables across survey respondents, and thus could generate bias (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Barberá, Ackermann and Venetz2017).

Third, using indices creates more robust measures by mitigating measurement error and leads to more precise regression estimates. The benefits of using composite measures are especially true of indices created using PCA, which extracts orthogonal features that explain most of the variance in the original data, concentrating the signal (rather than the noise) in the first few principal components (James et al., Reference James, Witten, Hastie and Tibshirani2013). We demonstrate this empirically, showing that the z−scores for the regression coefficients on the PCA dimensions are consistently higher than the z−scores for alternative measures (see section S3.3 of the SM). Our comparison of the z−scores demonstrates that our measures are less noisy and thus better for detecting relationships between the ideological and ethnocultural dimensions and vote choice.

In the second step, we use multinomial logistic regression to estimate the relationship between these two dimensions of group-based affect and vote choice. Because we expect vote choice to be related to these affective dimensions in different ways in Quebec and the rest of Canada, and because the set of alternatives for our outcome variable (vote choice) is different in Canada and Quebec (as the Bloc only contests seats in Quebec and the Reform Party only contested seats outside of Quebec), we estimate separate models for these two samples. Vote choice is measured in the post-election survey with a categorical variable that includes major and minor parties as well as a residual “Other” category for smaller parties (for example, the Green Party). We estimate vote choice as a function of the two main dimensions extracted from our PCA and control variables. The controls are party identification (categorical), age (categorical), income (categorical), gender (binary), university education (binary), non-European as ethnicity (binary), French as first language (binary) and Catholic as religion (binary).

The reader can find more details on the methods employed for the analysis in the SM. The SM includes three sections: S1 provides an overview of the PCA, S2 includes the regression tables used in the analysis, and S3 is dedicated to robustness checks.

Results

Group-based affect and vote choice

If we control for partisanship and socio-demographic features, do our measures of ideological and ethnocultural affect account for significant variation in vote choice? We answer this question by running a multinomial logistic regression of vote choice on the two affect dimensions. Note that we also check that our affect dimensions explain variation in vote choice that really captures group-based affect and is not related to policy attitudes. The results in section S3.4 of the SM show that the coefficients on the affect dimensions in the following analysis are robust to the inclusion of controls measuring relevant policy attitudes.

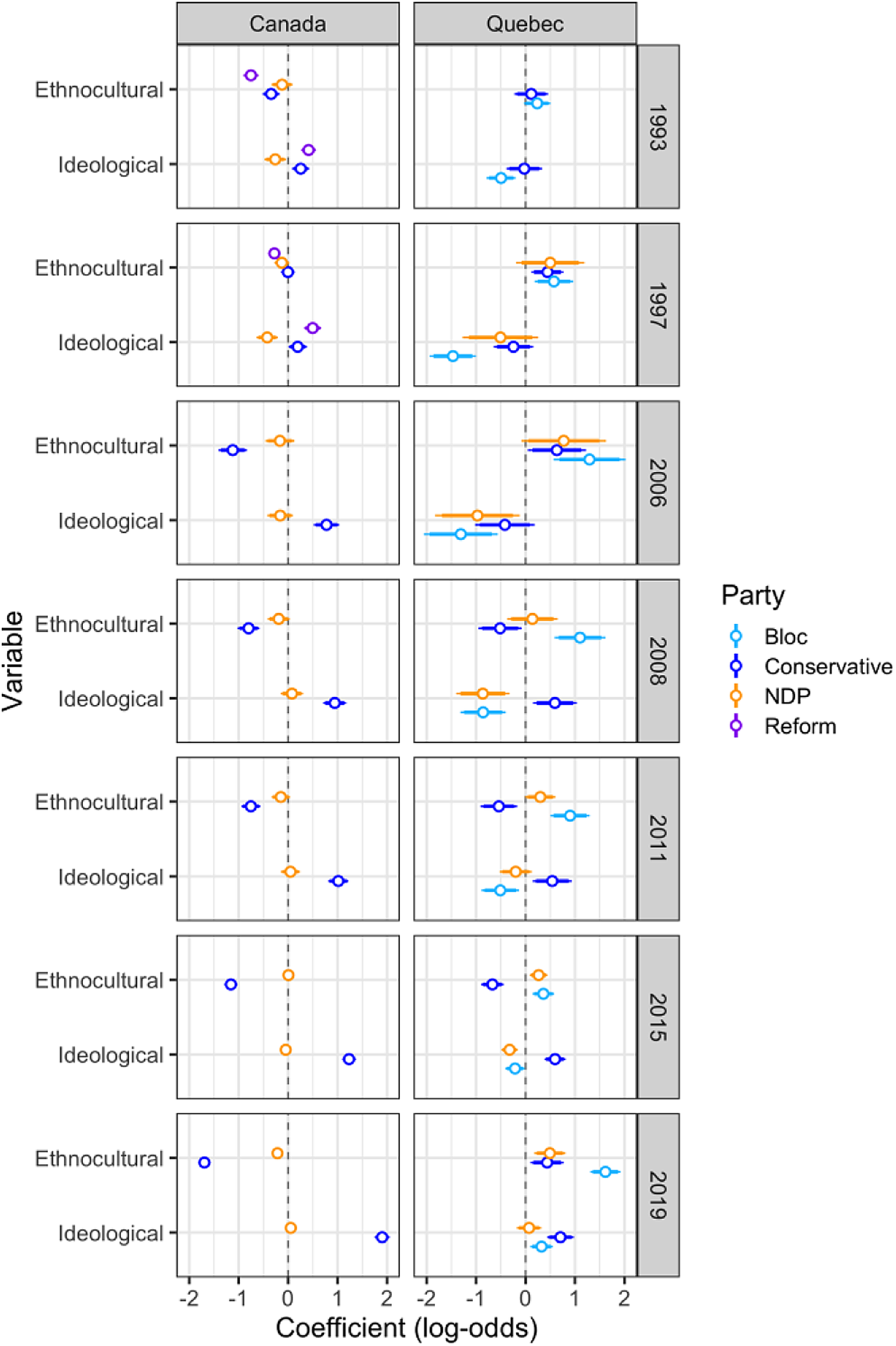

Figure 1 shows the standardized coefficients of the affect dimensions for each election and sample (see section S2 of the SM for the regression tables). The reference category on the outcome variable is the Liberal Party, and so the coefficients represent the difference in the log-odds of voting for a given party versus the Liberal Party for a one standard deviation increase on the independent variable. The thick band around the point estimate represents a 90 percent confidence interval, and the thinner band represents a 95 percent interval. Note that due to data sparsity, the NDP outcome category for the 1993 Quebec sample was assigned to the residual category. Note also that the label Conservative refers to the Progressive Conservative Party in the 1993 and 1997 elections and to the Conservative Party afterward.Footnote 9

Figure 1 Coefficient plot for the multinomial logistic regression of vote choice on ideological and ethnocultural affect. The models include controls for partisanship, age, income, gender, university education, non-European ethnicity, French-speaking and Catholicism. The reference category for the outcome is the Liberal Party.

The results offer a number of interesting findings. Starting with Canada outside of Quebec, we can see that higher ideological affect—warmer feelings toward groups associated with the ideological Right—significantly increased the log-odds of voting for either the Reform or Progressive Conservative parties relative to the Liberals in the 1990s, and they significantly increased the log-odds of voting Conservative relative to the Liberals from 2006 onward. The results also clearly show that the magnitude of the association between ideological affect (warmer feelings toward groups associated with the ideological Right) and voting Conservative has increased considerably over time.

With respect to ethnocultural affect, we can see that in the 1990s, higher levels of ethnocultural affect—or warmer feelings toward groups associated with Quebec relative to groups associated with multiculturalism—generally decreased the log-odds of voting Reform or Progressive Conservative relative to the Liberals. From 2006 onward, warmer feelings toward groups associated with Quebec significantly reduced the likelihood of voting Conservative relative to Liberal. The magnitude of this negative association between ethnocultural affect (where higher scores represent warmer feelings toward Quebec) and voting Conservative has also been increasing over time.

Continuing with our analysis of Canada outside Quebec with respect to the NDP, we can see that in the 1990s a one standard deviation increase in ideological affect (warmer feelings toward groups associated with the political Right relative to groups associated with the political Left) significantly decreased the log-odds of voting for the NDP relative to the Liberal Party. However, this association disappears over time. From 2006 onward, there is no association between ideological affect and voting NDP relative to the Liberals. Overall, there is also a null or negligible association between ethnocultural affect and the likelihood of voting NDP relative to the Liberals.

In Quebec, ideological affect as a predictor of voting NDP relative to Liberal is weakening over time as well. There is no statistically significant association between ethnocultural affect—or warmer feelings toward groups associated with Quebec relative to groups associated with multiculturalism—and voting NDP relative to Liberal for most elections. This changes from 2011 onward, where we find that voters who express warmer feelings toward groups associated with Quebec are significantly more likely to vote NDP than Liberal.

With regard to the Conservative Party, distinct trends are apparent in Quebec. Ideological affect does not predict voting Conservative relative to voting Liberal in Quebec until Prime Minister Stephen Harper's second election. From 2008 onward, warmer feelings toward groups associated with the ideological Right are significantly associated with higher log-odds of voting Conservative instead of Liberal in Quebec. In contrast to the rest of Canada, the association between having warmer feelings toward groups associated with the ideological Right and voting Conservative is smaller, and it does not grow with time. The association between ethnocultural affect and voting Conservative relative to Liberal in Quebec has shifted across elections. In most elections, having warmer feelings toward groups associated with Quebec was associated with lower log-odds of voting Conservative relative to voting Liberal in Quebec. However, in 1997, 2006 and 2019, the reverse is true.

Finally, the relationship between ideological affect and voting for the Bloc Québécois also shifts over time. From 1993 until 2015, an increase in ideological affect—or warmer feelings toward groups associated with the ideological Right—decreased the log-odds of voting for the Bloc relative to the Liberal Party. However, the magnitude of this coefficient has decreased over time, suggesting that feelings toward groups associated with the political Left or Right have become less important for the Bloc Québécois vote. By 2019, having warmer feelings toward groups associated with the ideological Right was significantly associated with an increase in the log-odds of voting Bloc Québécois relative to the Liberals. Unsurprisingly, higher scores on ethnocultural affect (warmer feelings toward groups associated with Quebec relative to groups associated with multiculturalism) are significantly and consistently associated with voting for the Bloc Québécois.

Discussion

Our analysis has important implications for understanding the history and future of party politics in Canada. First, congruent with Cochrane (Reference Cochrane2015), we find that ideological affect has become more important over time. More specifically, our analysis shows that feelings toward social groups—both ideological and ethnocultural affect—have become stronger predictors of the Conservative vote in Canada outside of Quebec. At the same time, the affective distance between the voters of left-of-centre parties has declined. From 2006 onward, ideological affect ceases to be meaningfully associated with voting NDP relative to Liberal in either Quebec or Canada outside of Quebec. Congruent with Johnston's (Reference Johnston2017) theory of polarized pluralism, we find that in Canada outside of Quebec, having warm feelings toward Quebec groups is associated with a higher likelihood of voting for the Liberals than other parties. The same is not true in Quebec, where voters with the warmest feelings toward groups associated with Quebec are often the least likely to vote Liberal. This usually benefits the Bloc Québécois on Election Day. However, Quebec voters with the warmest feelings toward groups associated with Quebec (and relatively cooler feelings toward groups associated with multiculturalism) have also swung for the Conservative Party. In sum, our results offer individual-level evidence for the contention that the Liberal Party has maintained its dominance by adopting a pro-Quebec stance in Canada outside of Quebec and, at least since the 1970s, a pro-multiculturalism stance in Quebec.

In contrast to the Liberals, the Conservatives have sometimes scored majority governments from the opposite strategy: an ends-against-the-middle coalition of Quebec nationalists and voters hostile to Quebec's demands in Canada outside of Quebec. We found evidence for this phenomenon that we will include in a separate paper. In summary, we find that two conditions are necessary for the Conservatives to capitalize on an ends-against-the-middle strategy for winning majority governments: a united Right and Quebec nationalists divided along the ideological dimension. When both nationalist voters who have warm feelings toward groups associated with the Right and nationalist voters who have warm feelings toward groups associated with the Left rally behind the Bloc Québécois, the Conservative Party cannot gain sufficient support in Quebec. We show that it is harder for the Conservatives to use the ends-against-the-middle strategy for winning majority governments because this second condition is less and less likely to be met. In 2019, nationalist-leaning Quebec voters across the spectrum of ideological affect were willing to vote in unison for the Bloc.

Conclusion

Our present analysis strengthens the existing research on Canada's party system by linking it to the growing literature on social identity theory and by empirically showing how individual voters’ feelings toward social groups in Canada animate the dynamics of the party system. Theoretically, we return to social identity theory's broader recognition that any perceived social groupings shape people's social judgments and behaviour.

While previous studies have tended to focus on a small number of mostly partisan groups, our empirical analysis of group-based affect in Canada includes voters’ feelings toward a range of social groups. We were able to include a larger number of variables measuring feelings toward different groups due to a methodological innovation: we used an unsupervised machine learning technique, principal component analysis (PCA), to reduce the dimensionality of affective space. PCA has only recently been applied to the study of party systems with very promising results (Magyar, Reference Magyar2021). We conducted PCA on the feeling thermometer ratings of twelve different groups in Canada: ethnic minorities, Indigenous peoples, gays and lesbians, feminists, Quebec, Canada, the United States, the federal Liberal Party, the federal Progressive Conservative Party/Conservative Party, the federal NDP, the Bloc Québécois and the Reform Party. PCA allowed us to reduce the dimensionality of our data by extracting two uncorrelated latent measures of group-based affect—ideological and ethnocultural affect—that we used as explanatory variables in subsequent regression analyses.

As social identity theory would lead us to expect, we find that group-based affect is a strong predictor of vote choice, a political act that has the potential to benefit certain groups over others. Our findings also substantiate the affective polarization thesis that feelings toward parties function like feelings toward social groups in general and are not merely a direct function of party politics. Recall that we controlled for party identification in every one of our models, and thus our findings represent the independent relationship between the affective components, including ideological affect, and vote choice. If feelings toward the parties were merely a direct function of party politics, then we would not expect to see any association between ideological affect and vote choice after controlling for partisanship. Instead, we find that even while accounting for partisanship, ideological affect is a strong and consistent predictor of vote choice and that the association between ideological affect and vote choice has been getting stronger over time.

One of the potential limitations of our present work is that the feeling thermometers used in our work differ from the measures used by social psychologists tapping into the warmth dimension of social judgment, which focus on perceptions. Rather than asking respondents to indicate how warmly they feel toward groups, social psychologists typically ask respondents to rate how warm or cold they view the other people or groups (for example, to rate whether the people of Quebec are typically warm or cold). However, interpersonal liking (whether people feel warmly toward groups) and warmth perceptions (whether people perceive other groups as being warm) are tightly correlated (Fiske et al., Reference Fiske, Cuddy and Glick2007: 79). Hence, our feeling thermometer variables should be a good proxy for warmth judgments, the primary dimension of social judgment.

Another potential limitation of our present work is that—because of the limitations of the data—we had to exclude theoretically relevant feeling thermometer ratings that were not asked consistently across elections. For instance, it would have been useful to include feeling thermometer ratings toward francophones, anglophones, immigrants, and white people, but these variables were not asked consistently across elections. Excluding what might be more salient social groups for political mobilization (such as francophones and immigrants) and limiting our analysis to social groups that might (arguably) be fuzzier proxies for these identities (such as Quebec and minorities) may have added noise to our analysis. Noisier measures would make it harder to identify meaningful components—and yet we were still able to recover the ideological and ethnocultural dimensions described by Johnston (Reference Johnston2019) using an unsupervised statistical learning technique (without instructing the algorithm to search for these dimensions) and to show that ideological and ethnocultural affect influence Canadian elections in theoretically expected ways.

Congruent with Canadian scholarship on polarization (Johnston, Reference Johnston2019; Cochrane, Reference Cochrane2015), our analysis offers evidence that the affective distance between supporters of left-wing and right-wing parties is growing. Ideological affect (warmer feelings toward groups associated with the Right) more clearly predicts voting Conservative relative to Liberal. Concomitantly, the gap between NDP and Liberal voters has closed. This suggests that the centre is fading away, restructuring the ideological dimension as a competition between the Left and the Right. Our analysis offers direct evidence of the individual-level mechanisms animating Johnston's (Reference Johnston2017) theory of Canadian polarized pluralism by illustrating the significant role that ideological and ethnocultural affect play in Canadian elections. In Canada, the ideological left/right cleavage can be summarized at the level of voter attitudes as ideological group-based affect. We also show that the divide regarding Quebec's place in a multicultural Canada can be summarized at the individual level as ethnocultural group-based affect. Across three decades, our findings show that ideological and ethnocultural affect have structured the vote in such a way that the Liberal Party has been able to occupy the centre on both dimensions, leaving the Conservatives with the strategy of winning majorities by crafting untenable ends-against-the-middle coalitions. Yet we also find that fault lines in the polarized pluralist structure of the party system have emerged in recent elections that were not covered by Johnston's (Reference Johnston2017) historical-institutional analysis. We uncover two trends that point to a dealignment of the party system. As we show in our present work, the Liberal Party is losing its grip on the centre. We also show that the Conservatives’ ends-against-the-middle coalition is becoming less viable as the Bloc is more successfully appealing to Quebec voters with warmer feelings toward groups associated with the Right—results that we develop further in a follow-up analysis.

Looking forward, the success of the Bloc in appealing to Quebec voters who feel warmly toward groups associated with the Right may prevent the Conservatives from crafting ends-against-the-middle coalitions. If right-leaning ideological affect—which should benefit the Conservatives—now benefits the Bloc, the Conservatives may become less competitive in Quebec. Moreover, as Conservatives voters’ feelings toward Quebec in the rest of Canada have become colder, it will be even harder for the party to appeal to Quebec nationalists in the same breath. One of the implications of this is that if the Conservatives are able to win government, they may increasingly do so without Quebec. As a result, Conservative governments, winning with the support of anti-Quebec voters outside Quebec and without Quebec nationalists, would be less motivated to seek concessions for Quebec, which could have consequences for Canadian unity.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423923000719.