Children, adolescents and young adults under 25 years of age (i.e. youth) are raised in an increasingly digitalised society, with technology as an integral part of daily life; some researchers suggest 30 years of age as a limit of youth, but there is not consensus on this.Reference Anderson and Jiang1 Social media is very attractive to youth as it is portable and offers ever-changing, immersive, diverse, individualised social engagement. The following social media platforms have launched since 2000: networks Facebook (2004), Twitter (2006) and LinkedIn (2002); media-sharing networks Instagram (2010), Snapchat (2011) and YouTube (2005); discussion forums Reddit (2005), Quora (2009) and Digg (2004); and bookmarking and content curation networks Pinterest (2010) and Flipboard (2010). Youth mostly use YouTube (81%) and Facebook (69%).Reference Anderson and Jiang1 Instagram and Snapchat are also commonly used, with the latter as the most important social network for 44% of youth.

Youth are vulnerable in many ways, and may need supervision with social media because of their limited ability to self-regulate, vulnerability to peer pressure and susceptibility to sharing personal information.Reference Madden, Lenhart and Cortesy2 Teenagers acknowledge social media's role in helping build their social connections and expose them to a diverse world, and cite concerns around the social pressure that it generates.Reference Anderson, Steen and Stavropoulos3 Most (65%) parents worry about their children spending too much time in front of screens, and its impact on mental and physical health, safety, well-being, social development and family dynamics.Reference O'Keeffe4 The USA Children's Online Privacy Protection Act has effectively guided participants since 1998, if and when those aged ≤13 years adhere to parental/guardian permission.5

Current state

This review attempts to describe and consider improvements to the literature about social media use in youth and young adults, as there are many things that are still unknown despite past studies and reviews.Reference Anderson, Steen and Stavropoulos3–Reference Sharma, John and Sahu16 How social media is used may make a difference in how it is experienced – from browsing through content to posting content to directed communication (e.g. conversational or liking content) – and if this is self-reported, methods are needed to monitor and verify. The positive and negative effects of social media related to clinical populations (i.e. normal versus problematic use) are not well described. Past studies and reviews are limited by the lack of consensus on definitions of terminology (e.g. normal versus problematic use, sexting, cyberbullying);Reference Anderson, Steen and Stavropoulos3,Reference O'Keeffe4,Reference Domahidi6 the quality of social-media-specific assessment tools and the rigor of other tools applied to social media; quality of study designs (e.g. cross-sectional or short-term designs that limit evaluation of outcomes) and summarising data, with emphasis on the better designs. Prior reviews found that social media use is negatively correlated with well-being,Reference Hoare, Milton, Foster and Allender7–Reference Twenge and Farley12 but the linkage to depression and/or lower self-esteem is not clear.Reference Orben11–Reference Vahedi and Zannella15 Many reviews reported both negative effects (low mood or esteem, decreased offline prosocial activity, overuse, impulsivity) and positive effects (developing friends, feeling connected, social capital).Reference Sharma, John and Sahu16 Unfortunately, many prior reviews did not clarify the relationship between social media and behavioural health issues (i.e. associative, mediating versus causal relationships).Reference Seabrook, Kern and Rickard8,Reference Twenge and Farley12 Ideally, more data from across the world is needed, rather than studies from a few countries.

This scoping review explores the question ‘What is the nature of the relationship (i.e. association, mediation, causation and/or other) between social media use in children/adolescents/young adults, psychopathology and mental and/or behavioural health conditions or problems?’. This review is intended to assist providers in educating adolescent/young adult patients and their families in how to best interact with social media. The review has several aims.

(a) To summarise findings of the relationship (association, mediation, causation) between social media use in children/adolescents/young adults, psychopathology and mental and/or behavioural health conditions or problems.

(b) To explore the unique challenges, effects and benefits of social media use by youth, related to clinical populations for depression and anxiety (Supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.523);Reference Akkın Gürbüz, Albayrak and Kadak17–Reference Ybarra, Alexander and Mitchell90 clinical challenges like cyberbullying, sexting and suicide (Supplementary Table 2);Reference Khasawneh, Chalil Madathil, Dixon, Wiśniewski, Zinzow and Roth91–Reference Mitrofan, Paul and Spencer123 and health behaviour and well-being (Supplementary Table 3).Reference Twenge and Farley12,Reference Alcott, Braghieri, Eichmeyer and Gentzkow124–Reference Ellison, Steinfield and Lampe149

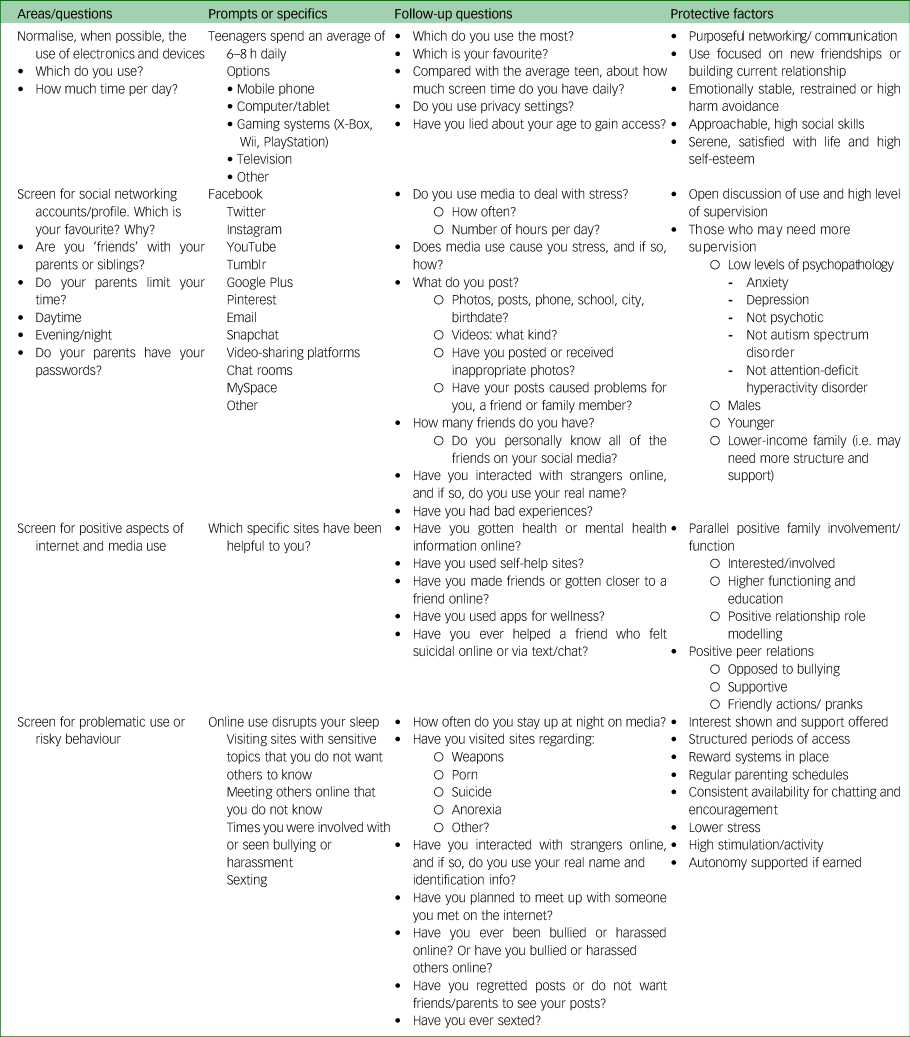

(c) Based on the literature, to provide an approach for future clinical research and approaches for providers and health systems to social media in youth (Table 1).

Table 1 Approach for providers to social media use by youth and young adults: clinical questions and protective factors

Method

Approach

The literature search was conducted from January 2000 to December 2020. The philosophical approach to the search was done according to the original six-stage processReference Arksey and O'Malley150 and updated modificationsReference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien151 (purposeful research question, identifying relevant studies, selecting studies based on an iterative process, charting the data, analysis of findings and consultation from stakeholders). The Preferred Reporting Extension for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) for scoping reviewsReference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O'Brien, Colquhoun and Levac152 has additional suggestions for sources of information, the search and appraising data.

Research question

This review addresses the overarching question: ‘What is the nature of the relationship between social media use, psychopathology and mental and/or behavioural health conditions or problems?’ The population of interest is children, adolescents and young adults (aged ≤25 years). Secondary questions are as follows.

(a) What social media is commonly used, in what ways and for what purpose(s) (i.e. approach, interest, motivation)?

(b) In what ways is social media helpful, neutral or negative related to clinical populations for depression and anxiety, and specific problems like cyberbullying, sexting and suicide?

(c) What is the relationship (i.e. association, mediation, causation and/or other) between social media (e.g. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram) and behavioural health?

(d) What methods of assessment, triage and approaches, interventions and professional development can help providers, parents, teachers and others in the community to help?

Identifying relevant studies

Eleven databases were queried: PubMed/Medline, APA PsycNET, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Web of Science and Scopus, Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and Google Scholar.

The search focused on youth (adolescent, child, children, high, junior, juvenile, middle, minor, secondary, teenager, youth) and social media use in five concept areas (Fig. 1): clinical depression and anxiety and problematic challenges (e.g. suicidal ideation, cyberbullying); quantitative data; social media mode; engagement and qualitative dimensions; and health and psychological well-being. Definitions were used based on consensus literature: bullying is a subset of aggressive behaviour that involves repeated and intentional attempts to damage/distress a weaker victim by a more powerful perpetrator;Reference Macaulay, Boulton and Betts153 and sexting is sending or receiving of sexually explicit pictures, videos, or text messages via smartphone, digital camera or computer.Reference Maheu, Drude, Hertlein and Hilty96 Exclusion criteria included studies focusing on anorexia, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, physical or intellectual disabilities, genetics, substance use, gambling, sleep/insomnia, cognitive disorders and aggression/violence beyond cyberbullying and suicide) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Search flow diagram for child, adolescent and young adult social media articles reviewed.

Study selection

One author (D.M.H.) screened titles and abstracts of potential references, excluding duplicates and those that did not meet the search criteria. Two authors (D.M.H., D.S.) reviewed the full text of remaining abstracts to find those meeting inclusion criteria; additional studies that met inclusion criteria were added from references.

Data charting

A data-charting form was used to extract data, and notes were organised with a descriptive analytical method. The reviewers (D.M.H., D.S.) compared and consolidated information by using a modified content analysis with thematic components;Reference Crowe, Inder and Porter154 a third author (A.J.M.) moderated any disagreement and a fourth author (S.-T.T.L.) analysed consistency of the approach. The information was shared with selected experts, their input summarised and themes extracted.

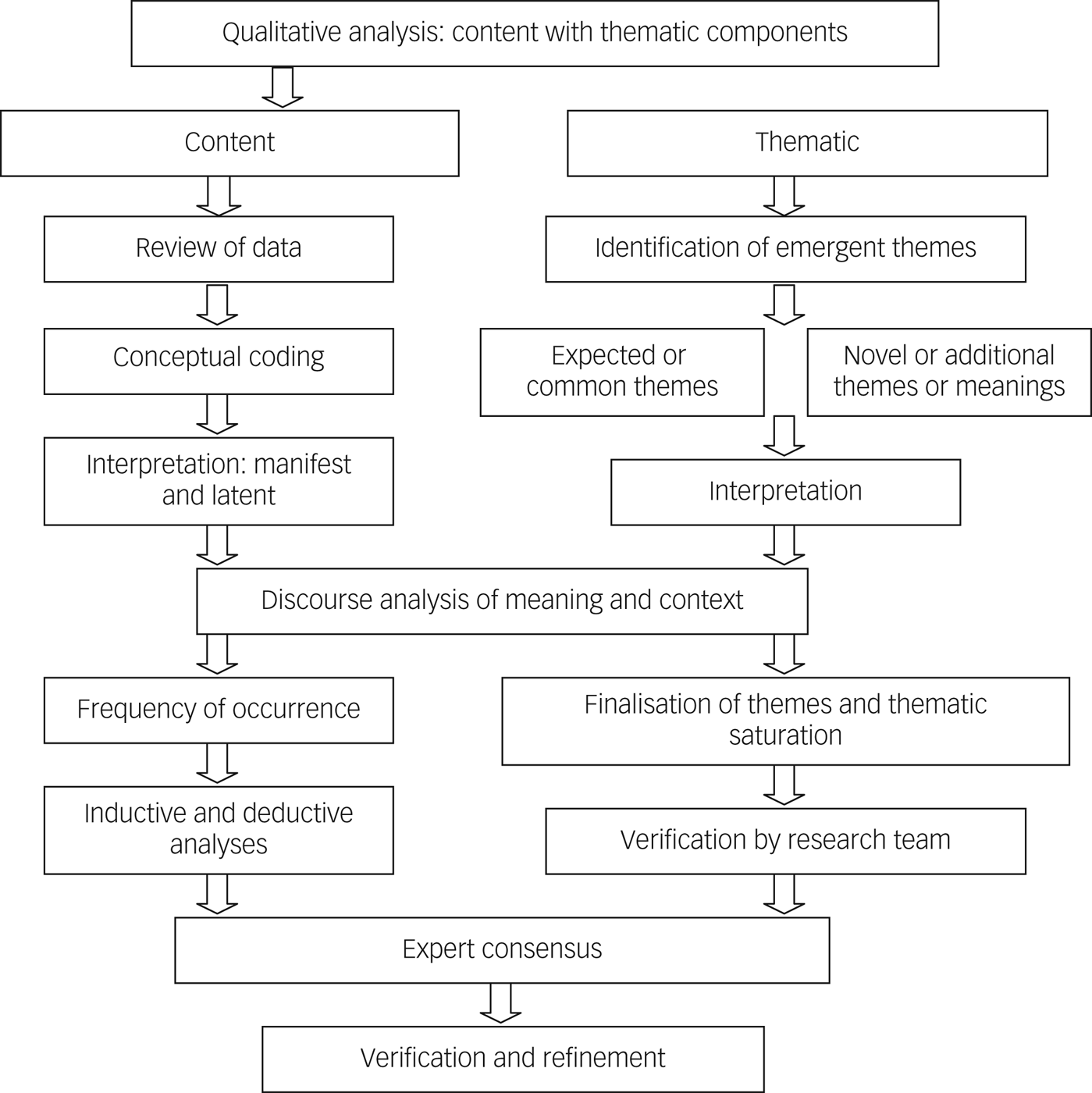

Analysis, reporting and the meaning of findings

Results were organised into tables, with key concepts and components outlined and described, partially based on excerpts from published topics. The studies varied considerably, and therefore were challenging to compare. Qualitative steps to analyse disparate populations, methods and data of studies were used (Fig. 2).Reference Crowe, Inder and Porter154 Content, discourse and framework qualitative analysis techniques were to analyse findings from papers and classify, summarise and tabulate the behavioural data; discourse and thematic analyses were used to search for themes and patterns; and framework analysis was used to sift through, chart and sort data in accordance with key issues and themes a series of steps (e.g. indexing, charting, mapping and interpretation).Reference Crowe, Inder and Porter154 Data in Supplementary Tables 1–3 are organised by study, sample size, population (e.g. country), objective and design, methods and measures, outcomes and clinical implications/challenges and training/research foci.

Fig. 2 Qualitative steps to analyse disparate study populations, methodology and data.

Expert opinions and feedback

Expert opinions were solicited to review preliminary findings and suggest additional steps for improvement. A list of relevant experts was compiled from (a) behavioural health organisations across professions internationally; (b) technology-related special interest groups of organisations (e.g. American Telemedicine; Medical, Nursing and Informatics Associations); (c) educational and professional development organisations (e.g. Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, American Academy of Pediatrics); (d) academic institutions and (e) researchers, authors, editors and editorial board members of journals related to social media.

Experts were invited by email (N = 24) and attended a live expert feedback session for discussion and feedback; completed a qualitative and quantitative five-item Likert scale survey (n = 20; 83.3%) and/or provided qualitative feedback via email (n = 4; 16.7%). The data charting and the search criteria plan were reviewed; their input did not suggest a search with additional terminology or otherwise change the scope. Input was summarised and themes were extracted to guide the organisation (e.g. headings in rows) and content (e.g. in the columns) of Table 1 and Supplementary Tables 1–3, based on previous work using consensus and modified Delphi processes.Reference Crowe, Inder and Porter154 Results showed that the majority agreed or strongly agreed that the search strategy was effective using the research question (n = 21; 87.5%); it was systematic/thorough (20; 83.3%); and adequately scientific in methodology (n = 18; 75%); and ‘[The tables] are organised in a practical way to summarise social media study findings for providers, teachers and systems’ (n = 20; 83.3%), once more specific outcomes were entered in the final column of each.

Results

Literature overview

Out of 2820 potential literature references, 112 duplicates and 2284 studies that were outside of the scope of this review were excluded (Fig. 1). Full-text review of 424 articles revealed that 128 met full inclusion criteria; 12 additional studies were found within those, for a total of 140 studies.Reference Twenge and Farley12,Reference Akkın Gürbüz, Albayrak and Kadak17–Reference Kırcaburun, Kokkinos, Demetrovics, Király, Griffiths and Çolak95,Reference Escobar-Viera, Whitfield, Wessel, Shensa, Sidani and Brown97–Reference Ellison, Steinfield and Lampe149,Reference Strasburger, Zimmerman, Temple and Madigan155 The studies focused on clinical populations for depression and anxiety,Reference Neira and Barber71 clinical challenges (e.g. suicidal ideation, cyberbullying)Reference Orben, Dienlin and Przybylski27 or psychological well-being.Reference Twenge21 Studies were of children aged 12 years and younger (n = 1; 0.01%), adolescents (13–18 years) (n = 72; 54.1%) and young adults (19–25 years) (n = 48; 34.2%); the rest were aggregates of the above (n = 18; 12.9%). The overall mean age was 18.78 years. The most common social media studied were Facebook (n = 62), Twitter (n = 20), Instagram (n = 11), YouTube (n = 6) and MySpace (n = 5). Studies varied in identifying gender identity (n = 63; 45%), ethnicity and race (n = 42; 30%) or neither (n = 35; 25%).

Most studies were cross-sectional cohort studies using self-report questionnaires. Few studies were longitudinal in design,Reference Coyne, Rogers, Zurcher, Stockdale and Booth19 had comparison groupsReference Nereim, Bickham and Rich20 or were randomised controlled trials.Reference Anderson, Steen and Stavropoulos3 Few studies used clinician/provider-administered instrumentsReference Madden, Lenhart and Cortesy2,Reference Nereim, Bickham and Rich20,Reference Yuen, Koterba, Stasio and Patrick30 or structured assessments.Reference O'Keeffe4,Reference Akkın Gürbüz, Albayrak and Kadak17,Reference Park, Lee, Shablack, Verduyn, Deldin and Ybarra51,Reference Park, Lee, Kwak, Cha and Jeong82,Reference Vanman, Baker and Tobin131 Timing or temporal dimensions are generally quite limited and studies span across acute disorders, subacute symptoms and trait/personality factors among a wide variety of ethnic, clinical and non-clinical populations. Broadly speaking, the studies looked at associations (n = 120; 85.7%),Reference Akkın Gürbüz, Albayrak and Kadak17–Reference Cole, Nick, Varga, Smith, Zelkowitz and Ford23,Reference Jensen, George, Russell and Odgers25–Reference Xie and Karan29,Reference Bayer, Ellison, Schoenebeck, Brady and Falk31–Reference Houghton, Lawrence, Hunter, Rosenberg, Zadow and Wood33,Reference Twenge, Joiner, Rogers and Martin36–Reference Calancie, Ewing, Narducci and Horgan41,Reference Kokkinos and Saripanidis43–Reference Coppersmith, Dredze, Harman and Hollingshead53,Reference Lup, Trub and Rosenthal55–Reference Preotiuc-Pietro, Eichstaedt and Park61,Reference Tandoc, Ferrucci and Duffy63–Reference Simoncic, Kuhlman, Vargas, Houchins and Lopez-Duran73,Reference Tsitsika, Tzavela, Janikian, Ólafsson, Iordache and Schoenmakers75,Reference De Choudhury, Counts and Horvitz76,Reference Jelenchick, Eickhoff and Moreno78–Reference Dumitrache, Mitrofan and Petrov84,Reference Pantic, Damjanovic, Todorovic, Topalovic, Bojovic-Jovic and Ristic86–Reference Kırcaburun, Kokkinos, Demetrovics, Király, Griffiths and Çolak95,Reference Escobar-Viera, Whitfield, Wessel, Shensa, Sidani and Brown97–Reference Pourmand, Roberson, Caggiula, Monsalve, Rahimi and Torres-Llenza100,Reference Chen102,Reference O'Dea, Larsen, Batterham, Calear and Christensen103,Reference Van Rooij, Ferguson, Van de Mheen and Schoenmakers105,Reference O'Dea, Wan, Batterham, Calear, Paris and Christensen112,Reference Sampasa-Kanyinga and Lewis114–Reference Pope, Barr-Anderson, Lewis, Pereira and Gao127,Reference Coyne, Padilla-Walker and Holmgren129–Reference Vanman, Baker and Tobin131,Reference Frith and Loprinzi133–Reference Blomfield-Neira and Barber142,Reference Farquhar and Davidson144,Reference Tsugawa, Mogi, Kikuchi and Kishino146,Reference Burke, Marlow and Lento148,Reference Ellison, Steinfield and Lampe149,Reference Crowe, Inder and Porter154,Reference Strasburger, Zimmerman, Temple and Madigan155 and mediating (n = 16; 11.4%)Reference Dempsey, O'Brien, Tiamiyu and Elhai24,Reference Yuen, Koterba, Stasio and Patrick30,Reference Niu, Luo, Sun, Zhou, Yu and Yang34,Reference Reinecke, Meier, Beutel, Schemer, Stark and Wölfling35,Reference Shaw, Timpano, Tran and Joormann62,Reference Steers, Wickham and Acitelli74,Reference Feinstein, Hershenberg, Bhatia and Latack77,Reference Locatelli, Kluwe and Bryant85,Reference Wang, Wang, Wu and Biao101,Reference Salmela-Aro, Upadyaya, Hakkarainen, Lonka and Alho104,Reference Sampasa-Kanyinga and Hamilton113,Reference Rasmussen, Punyanunt-Carter, LaFreniere and Norman128,Reference Mun and Kim132,Reference Coyne, Padilla-Walker, Harper and Stockdale143,Reference Vogel, Rose, Roberts and Eckles145 and causal (n = 4; 2.9%)Reference Frison and Eggermont42,Reference Lee-Won, Herzog and Park54,Reference Salmela-Aro, Upadyaya, Hakkarainen, Lonka and Alho104,Reference Burke, Kraut and Marlow147 relationships between social media and behavioural health issues.

Clinical populations, depression and anxiety

There were 78 studies of social media with outcomes in clinical populations and disorders (Supplementary Table 1). The mean age was 18.4 years (median 18 years) and included adolescentsReference Frison and Eggermont42 and young adults.Reference Twenge21 The study populations were diverse in terms of ethnicity, but were predominately White, and 46 studies were ≥50% female. The mean sample size was 8332.4 (median 310). The most common social media sites studied were Facebook (n = 37), Twitter (n = 10), Instagram (n = 5), MySpace (n = 2) and YouTube (n = 2); two were on screen time.Reference Keles, McCrae and Grealish13,Reference Houghton, Lawrence, Hunter, Rosenberg, Zadow and Wood33

Cross-sectional and longitudinal studiesReference Twenge and Farley12,Reference Coyne, Rogers, Zurcher, Stockdale and Booth19,Reference Brunborg and Andreas22,Reference Cole, Nick, Varga, Smith, Zelkowitz and Ford23,Reference Jensen, George, Russell and Odgers25,Reference Orben, Dienlin and Przybylski27,Reference Riehm, Feder, Tormohlen, Crum, Young and Green28,Reference Bayer, Ellison, Schoenebeck, Brady and Falk31,Reference Reinecke, Meier, Beutel, Schemer, Stark and Wölfling35,Reference Calancie, Ewing, Narducci and Horgan41,Reference Frison and Eggermont42,Reference Vernon, Modecki and Barber47,Reference Frison and Eggermont48,Reference Park, Lee, Shablack, Verduyn, Deldin and Ybarra51,Reference De Choudhury, Counts, Horvitz and Hoff65,Reference Gámez-Gaudix67,Reference De Choudhury, Counts and Horvitz76,Reference Koc and Gulyagci79,Reference Selfhout, Branje, Delsing, ter Bogt and Meeus87,Reference van den Eijnden, Meerkerk, Vermulst, Spijkerman and Engels89 of social media use and depression found that shorter periods of social media use (<3 h), particularly with purposeful or active engagement, are associated with better mood and psychological well-being, whereas longer periods of social media use predict depression (and often anxiety) or poorer psychological functionReference Brunborg and Andreas22,Reference Jensen, George, Russell and Odgers25,Reference Orben, Dienlin and Przybylski27,Reference Riehm, Feder, Tormohlen, Crum, Young and Green28,Reference Bayer, Ellison, Schoenebeck, Brady and Falk31,Reference Reinecke, Meier, Beutel, Schemer, Stark and Wölfling35,Reference Frison and Eggermont48,Reference Nesi and Prinstein59,Reference De Choudhury, Counts, Horvitz and Hoff65,Reference Selfhout, Branje, Delsing, ter Bogt and Meeus87 (particularly browsingReference Yuen, Koterba, Stasio and Patrick30,Reference van den Eijnden, Meerkerk, Vermulst, Spijkerman and Engels89 ), partly because of sleep disruptions.Reference Vernon, Modecki and Barber47 Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies are consistent with one prospective study that suggests a threshold effect around 3 h that has negative impact for many, but not all, users: low use-stable (80% at 3–4 h/day/item), high use-decreasing (12.3% at 4–5 h/day/item) and low use-increasing (7.3% at 3 to nearly 5 h/day).Reference Houghton, Lawrence, Hunter, Rosenberg, Zadow and Wood33 Two studies found that depression predicts social media useReference Houghton, Lawrence, Hunter, Rosenberg, Zadow and Wood33,Reference Gámez-Gaudix67 and reduces perception of support.Reference Park, Lee, Shablack, Verduyn, Deldin and Ybarra51 Specifically, Twitter use may be associated with depressive thoughts and symptoms, but only for people with low initial levels of in-person social support, and conveying positive sentiment helped to reduce depressive thoughts and feelings irrespective of people's level of in-person social support.Reference Cole, Nick, Varga, Smith, Zelkowitz and Ford23 Depressive signals observed in Tweets may predict future depression.Reference De Choudhury, Counts and Horvitz76 Instagram browsing was associated with increases in depressed mood in adolescents.Reference Frison and Eggermont42

Type of media use is important, since hours spent on social media and internet use were more strongly associated with self-harm behaviours, depressive symptoms, low life satisfaction and low self-esteem than hours spent electronic gaming and watching television.Reference Twenge and Farley12 In addition, girls generally demonstrated stronger associations between screen media time and mental health indicators than boys (e.g. heavy internet users were 166% more likely to have clinically relevant levels of depressive symptoms than low users for girls, compared with 75% more likely for boys). A cross-sectional study showed that cortisol systemic output was positively associated with Facebook network size and negatively associated with Facebook peer interactions.Reference Morin-Major, Marin, Durand, Wan, Juster and Lupien50

Studies of anxiety disorders are similar to findings in depression studies, with social anxiety symptoms mediated by spending more time on Facebook and passively using Facebook (i.e. viewing other's profiles without interacting).Reference Shaw, Timpano, Tran and Joormann62 In a study with three focus groups of those with anxiety disorders, six themes emerged: seeking approval, fearing judgement, escalating interpersonal issues, wanting privacy, negotiating self and social identity and connecting and disconnecting.Reference Calancie, Ewing, Narducci and Horgan41 A qualitative study revealed three types of negative use, including ‘oversharing’ (frequent updates or too much personal information), ‘stressed posting’ (sharing negative updates) and encountering ‘triggering posts’.Reference Radovic, Gmelin, Stein and Miller46 Both social anxiety and need for social assurance had a significant positive association with problematic use of FacebookReference Calancie, Ewing, Narducci and Horgan41,Reference Lee-Won, Herzog and Park54 or ‘fear of missing out’ (FOMO).Reference Dempsey, O'Brien, Tiamiyu and Elhai24,Reference Barry, Sidoti, Briggs, Reiter and Lindsey39

Clinical challenges like suicide, cyberbullying, sexting and other behaviours

The review found 34 studies on clinical challenges such as cyberbullying, sexting and posts on suicide (Supplementary Table 2). The primary populations were children (n = 1), adolescent (n = 15) and young adults (n = 14, with 3 for college students), with a mean age of 18 (median 17.9) years. The study populations were diverse in terms of ethnicity, but were predominately White and 15 studies were ≥50% female. The mean sample size was 34934.5 (median 524). The most common social media types studied were Facebook (n = 10), Twitter (n = 8), Instagram (n = 5), YouTube (n = 3) and MySpace (n = 2).

Excessive social media use, depression, suicide and school burn-out appear strongly related.Reference O'Dea, Larsen, Batterham, Calear and Christensen103,Reference Braithwaite, Giraud-Carrier, West, Barnes and Hanson107,Reference Coppersmith, Ngo, Leary and Wood109,Reference Zhang, Huang, Liu, Li, Chen, Zhu, Zu, Hu, Gu and Seng115 One longitudinal study found that, compared with matched non-suicide-related Twitter posts, suicide-related posts were characterised by a higher word count, increased use of first-person pronouns and more references to death.Reference O'Dea, Larsen, Batterham, Calear and Christensen103 In this study, emotional engagement, school burn-out and depression contributed to excessive social media use. Similarly, students with burn-out are at higher risk for depression and excessive social media use. Excessive social media use leads to school burn-out and school burn-out leads to excessive social media use. Individuals who were suicidal felt significantly less belongingness and significantly higher burdensomeness; they also use a higher proportion of achievement-related words and appear protective. Studies have compared artificial intelligence/machine learning to self-report measures to evaluate risk of suicide,Reference Braithwaite, Giraud-Carrier, West, Barnes and Hanson107 para-suicidal events,Reference Coppersmith, Ngo, Leary and Wood109 suicide-related TweetsReference O'Dea, Wan, Batterham, Calear, Paris and Christensen112 and other behaviors.Reference Zhang, Huang, Liu, Li, Chen, Zhu, Zu, Hu, Gu and Seng115 Machine learning can easily differentiate people who are at high suicidal risk from those who are not (linguistic inquiry and word count, decision tree and cross-validation analyses).Reference Braithwaite, Giraud-Carrier, West, Barnes and Hanson107 Machine-learning algorithms accurately identify the clinically significant suicidal rate in 92% of cases (sensitivity: 53%, specificity: 97%, positive predictive value: 75%, negative predictive value: 93%); a higher proportion of achievement-related words appears protective. For a single point of performance for comparison, artificial intelligence/machine learning had roughly 10% false alarms, but correctly identified about 70% of those who will attempt suicide.Reference Coppersmith, Ngo, Leary and Wood109

The relationship of depression, self-esteem and cyberbullying has been evaluated. A study of 8- to 13-year-olds evaluated whether cybervictimisation is prospectively related to negative self-cognitions and depressive symptoms beyond other types of victimisation.Reference Burnap, Colombo and Scourfield110 The majority of participants reported experiencing at least some degree of peer victimisation at either wave 1 or wave 2 (physical: 68.1%, relational: 89.8%, verbal: 87.9%, property related: 65.8%, cyber: 63.1%). Of note, 16.1% of participants obtained raw scores >75 on the Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale – Version 2 (RADS-2), and 8.1% obtained scores >82 (signifying mild and moderate depression, respectively). Victimisation was correlated with negative cognition and depressive symptoms; it predicted depressive symptoms; age and gender were not predictors of cybervictimisation or depression. Depression is associated with problematic social media use and indirectly predicted cyberbullying perpetration (associations were weak). Another study found that problematic social media use is weakly correlated with depression (r = 0.22), gender (r = −0.15), age (r = −0.13) and self-esteem (r = −0.11).Reference Kırcaburun, Kokkinos, Demetrovics, Király, Griffiths and Çolak95 Experiences of LGBTQ participants included both help for coping and cyberbullying leading to depression, stress and suicidal ideation.Reference Escobar-Viera, Whitfield, Wessel, Shensa, Sidani and Brown97

Bystander responses to suicidal behaviour and cyberbullying are in sharp contrast. Only 33.6% of participants left a positive, supportive comment on at least one of two suicide posts. Content severity, experience with a loved one's suicide attempts and use of Facebook to meet people were predictive of providing positive comments.Reference Corbitt-Hall, Gauthier and Troop-Gordon94 Positive bystander responses (PBRs) were higher in cyberbullying than traditional bullying incidents.Reference Crowe, Inder and Porter154 Females exhibited more PBRs across both types of bullying. Bullying severity affected PBRs, in that PBRs increased across mild, moderate and severe incidents, consistent across traditional bullying and cyberbullying. PBRs related to cyberbullying included (a) seek help from a teacher or parent, (b) seek help from a peer or friend, (3) direct intervention and (d) providing comfort or emotional support.

Provider access to a patient's social media could assist in identifying suicidal ideation and/or acts, since patients fail to disclose risk factors to physicians; however, there are ethical and privacy concerns about searching a patient's social media platforms.Reference Pourmand, Roberson, Caggiula, Monsalve, Rahimi and Torres-Llenza100

Health behaviour and well-being topics

There were 28 studies on health behaviour and well-being (Supplementary Table 3). The primary populations were adolescents,Reference Seabrook, Kern and Rickard8 college studentsReference Kelly, Zilanawala, Booker and Sacker14 and young adults.Reference Domahidi6 The study populations were diverse in terms of ethnicity, but were predominately White and 19 studies were ≥50% female. The mean sample size was 1558.8 (median 15.8). The most common social media types studied were Facebook,Reference Vahedi and Zannella15 Twitter (n = 2), Instagram (n = 1), YouTube (n = 1) and MySpace (n = 1). The most study population or disorder was depression (8) or anxiety (6).

Of the longitudinal studies, one found that a group deactivated from Facebook for 4 weeks showed small increases in well-being, but no changes in loneliness, compared with a usual use group.Reference Alcott, Braghieri, Eichmeyer and Gentzkow124 Another study over 2 months examined internalising symptoms (e.g. depression, anxiety and loneliness) related to the content of their Facebook communication and the responses they received from peers.Reference Ehrenreich and Underwood135 The mean number of posts was 60.2 overall (88 for girls and 37 for boys). For girls, internalising symptoms predicted negative affect, somatic complaints and eliciting support; they also predicted receiving more peer comments expressing negative affect and peer responses offering support. A study over 9 months evaluated how social media activity affected individual social communication skill and self-esteem.Reference Tsugawa, Mogi, Kikuchi and Kishino146 Active social media use (i.e. directed, person-to-person exchanges) increases bonding and bridging social capital and decreases loneliness; passive use does not.

Cross-sectional studies of teenagers examined psychological well-being and differences between girls and boys in use of technologies,Reference Twenge and Farley12 screen time Reference Orben, Dienlin and Przybylski27,Reference Orben and Przybylski125,Reference Orben and Przybylski126 and social networking services (SNS).Reference Blomfield-Neira and Barber142 The study found that adolescent girls spent more time on smartphones, social media, texting, general computer use and online, and boys spent more time gaming and on electronic devices in general.Reference Twenge and Farley12 Associations between moderate or heavy digital media use and low psychological well-being/mental health issues were generally larger for girls than for boys. For both girls and boys, heavy users (≥5 h) often rated twice as likely to experience well-being and mental health issues (e.g. risk factors for suicide) as low users. Also important was that the time 12th graders spent online doubled between 2006 and 2016; girls tend to spend more time in friendship dyads and boys in groups, and girls focus more on social relationships and popularity. A study of SNS and social self-concept, self-esteem and depressed mood found that the association between having an SNS and these negative indicators is more common with female youth; overall, frequency of SNS use is a positive predictor of social self-concept.Reference Blomfield-Neira and Barber142

With regard to college students, studies examined the relationship of social medial with well-being,Reference Rasmussen, Punyanunt-Carter, LaFreniere and Norman128 FOMO,Reference Hunt, Marx, Lison and Young130 attachment, social capitalReference Hunt, Marx, Lison and Young130 and social closeness based on activity.Reference Neubaum and Kramer139 Social media use is not associated with mental health problems, nor is emotional regulation; however, emotional regulation is associated with perceived stress and perceived stress is associated with mental health problems.Reference Rasmussen, Punyanunt-Carter, LaFreniere and Norman128 Social media use does not indirectly predict mental health problems as mediated by perceived stress or emotional regulation. Social media use may indicate challenges with mental health issues or be a way of dealing with difficult emotions. When attachment theory was used to explore individuals’ attachment orientations towards Facebook use related to online and offline social capital, a secure attachment was positively associated with online bonding, bridging and all capital, and offline bridging capital; an avoidant attachment was negatively associated with online bonding capital.Reference Lin138 Anxious–ambivalent attachment had a direct association with online bonding capital and an indirect effect on all capital through Facebook. Users in the study on social closeness spent 7.82 min consuming content and 3.13 min on participation.Reference Neubaum and Kramer139 Interacting with others on social media (e.g. commenting on updates) helps users feel closer to other people and this predicts positive emotional states after Facebook use. A study on FOMO involved two groups (10 min/day versus usual use), and both showed decreases in anxiety and FOMO; only the experimental group showed additional decreases in loneliness and depression.Reference Hunt, Marx, Lison and Young130 Moderation helps with mood and loneliness, and reduces anxiety and FOMO.

In a study on giving up Facebook, pre- and post-evaluation of perceived stress and well-being was measured by salivary cortisol between 14.00 and 17.00 h; those using Facebook had lower cortisol levels, less perceived stress, decreased life satisfaction and lower social loneliness on the Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale for Adults.Reference Vanman, Baker and Tobin131 One study examined that a user's activities on Twitter estimate a depressive tendency, based on a medium positive correlation (r = 0.45) between the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale and the model estimations of potentially meaningful words (≤20).Reference Tsugawa, Mogi, Kikuchi and Kishino146 Although a total of 99 words had absolute values of correlation coefficients with Zung scores >0.4, the highest scores were associated with the following words: even if, very, workplace, hopeless, disappear, too much, sickness, bad and hospital.

Implications for clinicians and researchers across clinical populations, problems and well-being

Findings of this scoping review inform approaches by providers, families and teachers when working with social media in children, adolescents and young adults (Table 1). To understand how technology affects the lives of adolescents and emergent adults, it is necessary to engage them in a conversation, share ideas and be available to help with problems. As many young people (and adults) may consider the internet their ‘lifeline’ to social engagement, consideration of the problematic aspects of internet use may be met with reluctance.Reference Domahidi6,Reference Twenge and Farley12,Reference Maheu, Drude, Hertlein and Hilty96,Reference Joshi, Stubbe, Li and Hilty156 Exploring beliefs, norms, values, cultural and language factors, and the meaning of technology to the individual, is integral to understanding and meeting the needs of each patient.Reference Sharma, John and Sahu16,Reference Cole, Nick, Varga, Smith, Zelkowitz and Ford23,Reference Dempsey, O'Brien, Tiamiyu and Elhai24,Reference Mun and Kim132 For providers, the value of forming and maintaining a trusting, therapeutic alliance with youth cannot be overstated, as quality care depends on patient–provider engagement, open and honest communication and shared decision-making for treatment.Reference Orben11,Reference Maheu, Drude, Hertlein and Hilty96,Reference Hilty, Torous, Parish, Chan, Xiong and Scher157

An accurate assessment or history is needed of online activities and associated health and risk factors. Internet use may be healthy or problematic, and this continuum may be explored with youth and parents via non-judgemental questioning to clarify the types and extent of technology used (Table 1).Reference O'Keeffe4,5,Reference Akkın Gürbüz, Albayrak and Kadak17,Reference Joshi, Stubbe, Li and Hilty156 Assessment is enhanced with multiple informants: parents, significant others, schools, primary care providers and/or others that know the youth well.Reference Joshi, Stubbe, Li and Hilty156,Reference Hilty, Torous, Parish, Chan, Xiong and Scher157 How they use their time, what they enjoy, how they want others to view them, awareness/use of privacy settings and proneness to risky behaviours is a snapshot of esteem and quality of relationships.Reference Hilty, Torous, Parish, Chan, Xiong and Scher157–Reference Zalpuri, Liu, Stubbe, Hadsu and Hilty159

Providers, families and others need an approach to promote healthy use of social media and prevent problematic social media behaviours. Data on the relationship of social media use and its impact on behaviour – association, mediation or causation – and clinical interventions are limited.Reference O'Keeffe4,5,Reference Dickson, Richardson, Kwan, MacDowall, Burchett and Stansfield9,Reference Kelly, Zilanawala, Booker and Sacker14,158 Nonetheless, positive family/home life, good engagement, supervision and other approaches may reduce risk of risky or dangerous behaviour.Reference O'Keeffe4,Reference Dempsey, O'Brien, Tiamiyu and Elhai24,Reference Bányai, Zsila, Király, Maraz, Elekes and Griffiths38,Reference Joshi, Stubbe, Li and Hilty156 A shared understanding is needed about healthy versus problematic use, how to monitor use and blending social media with alternative activities to meet emotional needs. Individual, peer/group and family education and therapy is often helpful. Motivational interviewing techniques may help co-construct a plan that meshes with values, with parent and provider input.Reference Anderson, Steen and Stavropoulos3,Reference Dempsey, O'Brien, Tiamiyu and Elhai24,Reference Joshi, Stubbe, Li and Hilty156

Discussion

This scoping review provides an update to past reviews on evaluation, interventions and outcomes of social media related to clinical populations (e.g. mood and anxiety disorders), clinical challenges (e.g. suicide, cyberbullying) and health behaviour and psychological well-being in youth.Reference Orben11,Reference Twenge and Farley12,Reference Kelly, Zilanawala, Booker and Sacker14–Reference Sharma, John and Sahu16,Reference Arksey and O'Malley150 This scoping review cast a much broader net and shows how substantial data can to contribute to diagnosis, monitor symptoms and collect ecologically rich behavioural data as a foundation for future interventions. Of 140 studies reviewed, longitudinal design,Reference Coyne, Rogers, Zurcher, Stockdale and Booth19 comparison groupsReference Nereim, Bickham and Rich20 and randomised controlled trialsReference Anderson, Steen and Stavropoulos3 were uncommon, resulting in association (n = 120; 85.7%), mediating (n = 16; 11.4%) and causal (n = 4; 2.9%) relationships between social media and behavioural health issues. Specifically, the review found that social media use of >3 h appears to be associated with increased depression and anxiety, and passive browsing of social media appears to be associated with depression/anxiety compared with purposeful, positive and active engagement; more research is needed to verify these findings. Girls/young women are more likely to be disproportionately affected by depression/anxiety with regards to social media, which is potentially mediated by the type of interaction, whereas boys/young men have more difficult experiences with gaming. However, positive social support inside/outside of social media is protective (Supplementary Tables 1–3). Some studies have overlooked the impact of equity, diversity and inclusion related to social media use, and care is needed so that technology does not inadvertently contribute to inequity and other injustices. Any of the many dimensions of diversity or differences (e.g. culture, ethnicity, race, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity, language, nationality, immigration status, socioeconomic status, geography) could affect evaluation and intervention.

Research into social media is moving towards standardised methods, interventions and evaluation measures. Studies are limited or have not looked at key issues, such as (a) sociodemographics and health, digital and language literacy; (b) clinical population state or trait; (c) passive consumption, broadcasting and directed purposeful or active engagement/communication; (d) quality of assessment measures (e.g. standardised, clinician/provider-administered instruments or structured assessments rather than self-report questionnaires without confirmation, verification, observation and corroboration); (e) temporal dimensions of symptoms and assessment; and (f) longitudinal design and comparison groups. More information related to equity, diversity and inclusion for the populations using social media, their families and the clinicians involved with assessment and care is needed to evaluate the impact of differences, cultural safety and humility and potential interventions.Reference Hilty, Crawford, Teshima, Nasatir-Hilty, Luo and Chisler160 This could include, but is not limited to, culture, ethnicity, race, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity, language, nationality, immigration status, socioeconomic status, spirituality, disability status, education, clinical diagnoses and geography. Implementation/ effectiveness designs – with longitudinal, quality of life and other dimensions – are also suggested,Reference Hilty, Torous, Parish, Chan, Xiong and Scher157 if well-anchored to health improvement.Reference Armstrong, McGee-Vincent, Juhasz, Owen, Avery and Jaworski161 Data from existing empirical foundations, hierarchical evaluation systems and statistical analyses for multiple comparisons and un/adjusted analyses are needed.Reference Hilty, Torous, Parish, Chan, Xiong and Scher157,Reference Armstrong, McGee-Vincent, Juhasz, Owen, Avery and Jaworski161,Reference Chancellor and De Choudhury162

Research into social media could be helped by other advances in artificial intelligence, informatics and cognitive computing methods. These advance data processing, stratify risk (e.g. suicide) and predict future negative outcomes with longitudinal correlation, predict biomarkers/digital phenotypes (e.g. depression during and after pregnancy) and allow patients or providers to intervene for moodReference De Choudhury, Counts, Horvitz and Hoff65,Reference De Choudhury, Counts and Horvitz76 and suicide.Reference Braithwaite, Giraud-Carrier, West, Barnes and Hanson107,Reference Coppersmith, Ngo, Leary and Wood109,Reference O'Dea, Wan, Batterham, Calear, Paris and Christensen112,Reference Zhang, Huang, Liu, Li, Chen, Zhu, Zu, Hu, Gu and Seng115,Reference McIntyre, Cha, Jerrell, Swardfager, Kim and Costa163 Challenging issues include unique populations (e.g. culture, youth, college), the trade-off of privacy versus suicide detection and comparing artificial intelligence approaches with traditional methods. Social media, like wearable sensors, is transforming care by moving from manual transfer of subjective self-reported information during a patient visit to an integrated, longitudinal, minimally intrusive and interactive sharing of data based on the ecology of a person in their natural setting.Reference Garcia-Ceja, Riegler, Nordgreen, Jakobsen, Oedegaard and Tørresen164,Reference Hilty, Armstrong, Luxton, Gentry, Luxton and Krupinski165 Artificial intelligence inferential techniques (i.e. applied or performing functions similar to human thinking and analysis) have high predictive power and are reusable; suicide hotlines and face-to-face evaluations are effective methods for suicide intervention, but depend on action by the person with suicidal ideation.

Providers, parents/families and healthcare systems are facing challenges with social media, partly related to how youth live and how their developing brains are shaped by peers and the pervasive influence of technology.Reference Joshi, Stubbe, Li and Hilty156 There are a range of behaviours across teenagers, adolescents and other age groups, and so a behaviour may be normal for one group and not for another; a behaviour may be healthy or problematic, depending on age. Families, teachers and providers can use data to engage youth with non-judgemental questioning about social media use, use preventive/risk factors for making decisions and, most importantly, stay as close as possible to their young loved ones who may be at risk for hurting themselves – while privacy is important on one hand, notification of families, clinicians and others who could help them may be helpful. Resources are also available from the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Media and Communication Toolkit and Family Media Use Plan,158 and other agencies.166 Competencies for social media, mobile health, wearable sensors and other asynchronous technologiesReference Hilty, Torous, Parish, Chan, Xiong and Scher157,Reference Zalpuri, Liu, Stubbe, Hadsu and Hilty159 include suggestions for training programmes (undergraduate/medical student, graduate/resident). These also address professional development of faculty and institutional change of health systems or academic centres to integrate videoReference Hilty, Unutzer, Ko, Luo, Worley and Yager167 and asynchronous technologies.Reference Hilty, Torous, Parish, Chan, Xiong and Scher157

Scoping reviews appear more helpful than other types of reviews for evaluating the broad context, asking questions of the literature and generating questions, approaches, questions and methodologies for current and target states of research.Reference Vidal, Lhaksampa, Miller and Platt168 There are limitations to this scoping review. First, a small team conducted the study selection and review, with only one reviewer screening all titles and abstracts. Second, a modified content analysis with thematic analysis components was presented, rather than a quantitative/numerical analysis of the extent and nature of the studies. Similarly, we categorised data into clinical disorders, but a different framework that looks at health from a functional perspective may have been a better option, such as the health continuum (from poor health/illness/languishing to good health/positive health/flourishing). Third, a quality evaluation tool was not used, partly because the diversity of study methodologies, duration and data collection make a thorough integrated review challenging, using a systematic quality evaluation system or the equivalent of a quantitative meta-analysis. In addition, a measure of risk of bias was not used, and is suggested when applicable and possible. There is also an inherent bias in studies of youth populations published in peer-reviewed literature. Cross-sectional studies of associations with multiple factors in applied rather than controlled settings have limitations. Fourth, the review does not cover all of the potentially relevant psychological well-being, stress and related life dimensions of youth. Fifth, this study did not assess if age or other sociodemographic characteristics were associated with or predicted types of social media use; furthermore, future studies and reviews may take the literature further by distinguishing between populations aged ≤17 years and those aged 18–25 years, as well as not extending this to 30 years of age. Sixth, broader input for consensus across organisations could have been helpful, and a qualitative, small-group interview approach with experts, using a semi-structured guide, could have discovered more information. Seventh, the review falls short of covering all psychiatric disorders (e.g. bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, developmental and other childhood disorders). Eighth, the review has some specific findings, yet points out generalised themes and questions; it is not a conclusive data analysis like a systematic review. Lastly, it is important to recognise the digital divide in social media use across different youth and sociodemographic populations, particularly for low-income, equity-seeking and deserving populations and populations in Latin America, Asia, Africa and Oceania.

In conclusion, research is moving forward on evaluation, intervention, monitoring and outcomes of social media use in youth related to clinical disorders, challenges like suicide and cyberbullying, and psychological well-being. Families, teachers and providers can use current data to engage youth with non-judgemental questioning about social media use and be aware of preventive/risk factors. Longitudinal comparison designs, effectiveness approaches, artificial intelligence and biomarking/digital phenotyping may provide a foundation for future interventions to examine causal relationships between social media use and behavioural health. Research opportunities and challenges can be broadly organised into the following categories: clinical outcomes from a functional perspective on a health continuum; diverse youth and sociodemographic populations, with age stratification by consensus, if possible (e.g. early adulthood to age 25, 30 or 34 years); methodology, models and data analytic approaches; development of consensus by ‘youth experts’ to provide input on the results and suggest youth-led and other intervention initiatives; study of human-computer-human interaction and privacy issues that inform policy. Whether effectiveness research on social media use can lead to better overall health outcomes and reduced disease burden is still unknown. Analysing large amounts of data will require close collaboration between partners from diverse areas of expertise, such as researchers, providers, statisticians, software developers and engineers. Health systems need to explore competencies for providers to place the person's/patient's needs first and embrace social media technology within healthcare reform, and this will require adjustment of clinical, training, professional development and administrative missions and workflow.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.523

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the American Telemedicine Association and its Telemental Health Interest Group, as well as the Departments of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and Pediatrics at the University of California, Davis School of Medicine, and the Veterans Affairs Northern California Health Care System Mental Health Service. They also thank the Expert Opinion Panel from behavioural health, technology, education and professional development, as well as researchers, authors, editors and editorial board members of journals. The help provided assisted with the recruitment of the expert panel, looked at the data and provided staff support for the authors.

Author contributions

All authors met the three criteria (substantial contribution, drafting, final approval) and agree to be accountable for the work.

Funding

None.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.