Introduction

The dramatic expanse of the Covid-19 pandemic has disrupted lives, livelihoods and communities and was described as ‘the once-in-a-century pathogen’.Footnote 1 The epidemic disease is not only a public health crisis; it has also harshly affected the global economy and financial market by significantly increasing the rate of unemployment, and causing severe disorders in the transportation, service, and manufacturing businesses in many countries. As a result, European policymakers have advanced the idea that ‘all stakeholders, especially global business, must urgently come together to minimise its impact on public health and limit its potential for further disruption to lives and economies around the world’.Footnote 2 Accordingly, corporations are required to engage in stakeholder-supportive actions to endure a durable viability of the company and to preserve a sustainable society and economy.Footnote 3 One prominent manifestation of a potential mismatch between the interests of insiders and outsiders in corporate governance that may affect long-term growth of national economies is the conflicts of interests between controlling and minority shareholders.Footnote 4 In particular, controlling shareholders may abuse corporate resources by transferring assets out of the firms via transfer pricing, subsidising personal loans, or higher compensation for executives control to the disadvantage of minority shareholders. Another form of extracting private benefits of control is manifested through tunnelling, which can be carried out more easily under different legal arrangements, such as dual-class shares, stock pyramids, and cross-holdings.Footnote 5 Consequently, different legal systems employ legal strategies to mitigate agency costs between controlling and minority shareholders. For instance, the design of the composition of the board of directors is carried out in a manner that enhances the ability of minority shareholders to voice their opinion in the decision-making process of the company. Alternatively, the law may protect minority shareholders by increasing their direct decision rights over fundamental corporate resolutions, such as supermajority approval requirements.Footnote 6 This study is devoted to exploring another primary strategy –that of imposing loyalty and care obligations on the controlling shareholder towards the corporation, which implicitly extends to minority shareholders as well.

A systematic review of the transnational law on the loyalty and care obligations of controlling shareholders reveals different doctrinal approaches in this subject. According to the American approach, the controlling shareholder is subjected to an ex ante equitable fiduciary obligation, which involves the subordination of his interests to those of minority shareholders and the company. In contrast, English law does not consider controlling shareholders as fiduciaries, and they are not subjected to fiduciary duties towards minority shareholders or the company. Instead, the relationship between controlling and minority shareholders is regulated through ex post equitable judicial review of the unfair prejudice remedy. Under the civil law's approach, the relationship between controlling and minority shareholders is governed by a contract or by quasi-contractual mechanisms, and is an extension of the traditional duty of good faith embodied in obligations law.

This study aims to uncover the evolution of divergent doctrinal choices for regulating the loyalty obligations of controlling shareholders, by employing a law-in-context methodology.Footnote 7 This approach seeks to explain the similarities and differences of governance choices by exploring the cultural, historical and socio-economic backgrounds of a given legal system in which organisations and decisions are implanted.Footnote 8 Moreover, ‘[p]utting law in context aims at understanding the law, as a foreigner to that legal system and, hence, explaining why the law is as it is’ by examining various institutional contexts.Footnote 9 Therefore, I conduct a macro-level inquiry which focuses on the cultural environment and business history developments in Anglo-American and civil legal systems to understand the different doctrinal designs of the obligations of controlling shareholders towards minority shareholders and the company. Specifically, I argue that those dissimilarities are a result of different cultural-non-formal norms of corporate governance regarding the protection provided to shareholders in relation to the interests of other constituencies. Moreover, the different doctrinal choices are the result of historical developments of the law of corporate groups, which is perceived as alternative formal legislative arrangements to court-made loyalty obligations of controlling shareholders.

This study is structured as follows. In Section 1, I discuss the policy considerations for and against imposing strict loyalty and care obligations on controlling shareholders in the form of fiduciary duties. Section 2 is devoted to explaining how the cultural norms of corporate governance systems have affected the doctrinal design of the loyalty and care obligations of controlling shareholders. In particular, I argue that jurisdictions which have adopted the shareholder value maximisation norm in its extreme form have subjected controlling shareholders to broader fiduciary duties, in order to prevent them from utilising the preferable protection provided to shareholders’ interests to deprive private benefits of control. In Section 3, I examine the business history of corporate groups in the United States, Germany and the UK. I argue that imposing fiduciary obligations on controlling shareholders was partly motivated by the need to eliminate this concentrated ownership structure, as it was determinant to economic growth. Section 4 briefly discusses the policy implications of the macro-level investigation for the debate over global convergence of corporate governance and norms. Section 5 summarises my conclusions.

1. Controlling shareholders’ fiduciary duties: purposes and basic concepts

(a) Controlling shareholders as fiduciaries: policy considerations

Generally, imposing fiduciary duties on controlling shareholders is perceived as an ex ante mechanism for preventing the extraction of private benefit of control at the expense of minority shareholders in concentrated ownership structures of public companies.Footnote 10 Since controlling shareholders are provided with significant powers to direct the company's decision-making process, there is a concern that such powers will be applied not in accordance with the best interests of the company.Footnote 11 The broad authority given to controlling shareholders to direct the company's affairs can affect the wellbeing of various constituents involved in the company's operations. For instance, a controlling shareholder may act to alter the provisions of the charters and by-laws, approve significant transactions such as freeze-outs, and liquidate the company assets. Such actions could be employed to advance his sole benefit at the expense of the company and stakeholders’ interest.Footnote 12 Moreover, because very often the senior management and board of directors are dominated by the controlling shareholder, there is a concern that they hold valuable information regarding the company's operations that is not shared with minority shareholders and other stakeholders. Without access to such information, minority shareholders do not hold the necessary means to assess the conduct of the controlling shareholder and directors and to determine whether their actions were carried out solely for the benefit of the corporation.Footnote 13 Given the fact that it is impossible to predict every potential conflict of interest between the company and the controlling shareholders, and to constrain them by specific ex ante arrangements to comprehensively secure the interests of minority shareholders, the law may obligate the controlling shareholder to employ his general powers with loyalty and due care.Footnote 14 Therefore, when such duties are introduced, they are generally directed towards minority shareholders and the company.Footnote 15

At the same time, several arguments can be presented against perceiving controlling shareholders as fiduciaries. First, imposing fiduciary duties on the controlling shareholder by subordinating his interests to those of minority shareholders will undermine his ability to carry out his idiosyncratic business vision regarding the company's actions.Footnote 16 For example, Goshen and Hamdani have argued that controlling shareholders will bear costs involved in concentrated ownership structures, such as the costs of monitoring management conduct, not necessarily because they want to divert private benefits of control but because such an ownership structure allows them to realise their vision of the company's long-term interests.Footnote 17 Controlling shareholders will bear these costs because they believe that such an ownership structure will enable them to carry out long-term visions for the company's business activities that will provide future profits for the benefit of all stockholders.Footnote 18 Moreover, even if the concern about extracting private benefit of control at the expense of minority shareholder is indisputable, imposing fiduciary duties on the controlling shareholder is not, fundamentally, appropriate. This is mainly because eliminating the extraction of any private benefits that the controlling shareholder may obtain reduces his commitment to act in favour of advancing long-term interests.Footnote 19 Therefore, rather than adopting a policy that completely negates the use of legal measures that entrench the controlling shareholder, a more lenient policy should be adopted that allows the controlling shareholder to derive optimal private benefits to ensure the fulfilment of the company's long-term goals.Footnote 20

Secondly, it is questionable whether the mere existence of information asymmetry between controlling and minority shareholders can justify subordinating the controlling shareholder to comprehensive fiduciary duties. In particular, the perils of any potential information asymmetry between different groups of shareholders are dependent on the exact power relation between controlling and minority shareholders as manifested in their equity shares and voting rights. It can be assumed that the larger the capital and voting rights of minority shareholders, the more substantial their access to valuable information shared in the discussions of the board of directors.Footnote 21 Hence, the sharing of valuable information between controlling and minority shareholders is justified mainly when the latter can significantly contribute to the decision-making process of the company.Footnote 22 Accordingly, a clear distinction is in order between information rights provided through securities law to retail investors who generally do not participate in the decision making process of the company,Footnote 23 and information rights provided to sophisticated and informed shareholders, who can use the information to enhance effective corporate performance practices.Footnote 24

Thirdly, even if the entire factual instances which may involve conflict of interests between controlling and minority shareholder cannot be predicted, this does not necessarily justify imposing fiduciary duties on the controlling shareholder. The reason for this is that it is not the intention of the law to eliminate all conflicts of interests. Rather it aims to ensure that the benefit to the company is protected when conflicts are present. For instance, the law stops short of annulling related party transactions as such,Footnote 25 because they do not specifically entail the tunnelling of resources.Footnote 26 In some cases those transactions can advance the company's businesses for the benefit of all stakeholders involved in the company's operations.Footnote 27 Alternatively, in some instances, allowing the company to engage in related party transactions is a sort of a compensation that has to be conveyed to the controlling shareholder for the monitoring activities carried out by him for the benefit of all constituencies.Footnote 28 Therefore, while the divergent interests of controlling and minority shareholders are well recognised,Footnote 29 there is disagreement about how to police the possible misbehaviour of a controlling shareholder.Footnote 30 The following part discusses different doctrinal positions across various legal systems.

(b) Doctrinal strategies for monitoring controlling shareholder's misconduct: an international survey

(i) American law: ex ante equitable obligation

Delaware law constrains the potential misbehaviour of controlling shareholders by subjecting them to fiduciary obligations.Footnote 31 Under Delaware law, a controlling shareholder is a stockholder who either: (1) controls a majority of the company's voting rights;Footnote 32 or (2) exercises ‘a combination of potent voting power and management control such that the stockholder could be deemed to have effective control of the board without actually owning a majority of stock’;Footnote 33 and (3) a group of otherwise unaffiliated shareholders may be considered a controlling shareholder if those shareholders establish a group by signing a contract, voting trust, or other agreement that provides them controlling voting power.Footnote 34 While stockholders do not generally owe fiduciary duties, a controlling stockholder assumes fiduciary duties similar to those directors.Footnote 35 Accordingly, a controlling shareholder holds duties of loyalty and care that require him to act in the best interests of the company and its stockholders.Footnote 36

Moreover, transactions involving controlling stockholders are generally subject to the standard of review of entire fairness rather than the default business judgment rule, which prevents second-guessing the judgement of the board.Footnote 37 Under the entire fairness standard, the controlling shareholder has to establish that the transaction is fair from a commercial perspective (‘fair price’) and it was negotiated, structured and disclosed justly and reasonably (‘fair dealing’). Still, that burden may shift to the plaintiffs if the controlling shareholder can prove that the conflict transaction was approved by a ‘well-functioning committee of independent directors’, with ‘no compulsion’ to reach an agreement.Footnote 38 Recently, in the seminal MFW case,Footnote 39 the Delaware Supreme Court adopted a solution that incentivises the corporation to seek prior approval from both an independent director committee and a majority of minority shareholders.Footnote 40 According to this ruling, freeze-out transactions will be subjected to deferential business judgement review rather than the entire fairness standard if the merger is structured to include certain procedural safeguards for minority shareholders.Footnote 41

(ii) English law: ex post equitable judicial review

The UK differs from other countries in its laws to constrain the misbehaviour of controlling shareholders.Footnote 42 English law does not accept that shareholders should be perceived as fiduciaries, and thus refrains from imposing fiduciary duties on controlling shareholders towards minority shareholders or the company.Footnote 43 Moreover, it is essential to bear in mind that – unlike the United States’ position – in the UK, ‘a trustee's duty to exercise reasonable care, though equitable, is not specifically a fiduciary duty’.Footnote 44 Controlling shareholders are not compelled by the rigorous duties that the law imposes on directors, such as the duty not to make a profit out of their trust and to avoid all circumstances where their personal interest may differ from the interests of the company. Accordingly, ‘when a shareholder is voting for or against a particular resolution he is voting as a person owing no fiduciary duty to the company and who is exercising his own right of property, to vote as he thinks fit’.Footnote 45 While the English case law acknowledges the general equitable principle demanding shareholders to act in the best interest of the company when amending the company's articles of association,Footnote 46 the relationship between controlling and minority shareholders is mainly regulated by the ex post unfair prejudice remedy, according to section 994 of the Companies Act 2006.Footnote 47 This remedy generally applies to small, quasi-partnership companies and is not necessarily appropriate for regulating the relationship between different shareholders in large listed companies.Footnote 48 Although this remedy has been practised mostly in private companies, where a minority shareholder can demonstrate his legitimate expectations when he entered the company, English legislation does not include any statement preventing a specific shareholder in public company from bringing an action based on unfair prejudice.Footnote 49

There are two elements to the requirement of unfair prejudice. Both must be presented to succeed in a claim: (1) the conduct must be prejudicial, thereby causing harm to the relevant interest of the members or some part of the members of the company (ie shareholders); and (2) it must be unfair.Footnote 50 The unfair prejudice is based on an objective test which provides that the petitioning shareholder does not need to demonstrate that the controlling shareholder acted in bad faith or intended to cause prejudice. The courts will regard the prejudice as unfair if a hypothetical reasonable bystander believes it to be dishonest. Accordingly, the court will examine whether the conduct of which the shareholder complains is compatible with the contractual terms included in the Articles of Association of the company and any shareholders’ agreement.Footnote 51 Several other common law countries followed the English approach by extending the authorised parties who are entitled to plead oppression.Footnote 52 For example, Canadian law does not limit the remedy solely to shareholders and allows the granting of similar relief to other stakeholders, including creditors and employees.Footnote 53

(iii) Civil law: bona fide obligation

Various scholars have pointed out that civil law countries impose general duties of loyalty and care on controlling shareholders and directors similar to the position under US law.Footnote 54 For instance, in recent decades, German courts have enlarged the duty of loyalty from directors to controlling shareholders, which is directed towards the company and minority shareholders.Footnote 55 In a 1988 decision, the Federal Supreme Court concluded that a controlling shareholder has a duty of loyalty to the minority shareholders.Footnote 56 In a subsequent 1995 case, the court ruled that a minority shareholder that had de facto veto power over a transaction critical to the company's survival due to a supermajority requirement is also subject to an ad hoc duty of loyalty.Footnote 57 Civil law does not recognise a special concept of a fiduciary, and relationships deemed ‘fiduciary’ are governed by contract or quasi-contractual mechanisms.Footnote 58

While US and civil law may share similar terminology or rhetoric concerning the fiduciary duties of corporate organs, there are at the same time significant differences in how those obligations are perceived.Footnote 59 The US law view provides that fiduciary relationship should not be identified with contractual dealings.Footnote 60 In particular, while contractual parties define their rights and obligations at the drafting stage, parties to fiduciary relationships represent a selection of a pre-existing governance framework.Footnote 61 This framework involves several norms that define the fiduciary relationship which fiduciaries are obligated to comply with. These norms are needed to mitigate the risk of betrayal and to prevent the principal from constantly monitoring other people's conduct. For instance, because a fiduciary voluntarily undertakes to subordinate his interests to those of the principal, the latter can be optimistic that the former will not only be competent but also be committed to doing what he trusted him to do for the right reasons.Footnote 62 While contractual parties are expected to bargain on a self-interested basis bounded by the terms of their contract, fiduciaries are obligated to advance the principals’ interests within the scope of the fiduciary relationship.Footnote 63 Thus, the precise nature of fiduciary duties under German law is far from clear. As Gelter and Helleringer clarify:

These [fiduciary] duties are not necessarily considered categorically different from the contractual obligations described so far; rather, they exist on a continuum. A possible distinction should, however, be noted: whereas in most contracts, loyalty obligations are merely accessory to the main duty to perform, in cases analogous to fiduciary relationships, the duty of loyalty is the main contractual duty. For example, German scholarship appears to be divided on the precise nature of these duties. According to one view, the duty of loyalty under corporate law should be understood as rooted in the ‘good faith’ provision of the law of obligations, and thus essentially constitute a more demanding version of it … Other scholars argue that the duty of loyalty is categorically different from good faith because the former is one of the essential obligations in relationships where it applies, whereas the latter is merely a generally applicable incidental duty.Footnote 64 (emphasis added)

As the common law's sharp distinction between status, contract and fiduciary relationship is not recognised in the civil law,Footnote 65 the conception of the fiduciary is generally understood in contractual terms.Footnote 66 The duty of the fiduciary is perceived as a specific instance of the general good faith requirement of the law of obligations. For example, France has regulated the loyalty duties of controlling shareholders by employing the doctrine of abuse of majority powers (abus de majorité), which restricts majority shareholders’ freedom to vote as they wish at general meetings.Footnote 67 Accordingly, a controlling shareholder cannot use its voting rights in a manner that inflicts damages on the company and minority shareholders.Footnote 68 Furthermore, the loyalty duties are not confined solely to majority shareholders but also apply to minority shareholders through the court-made doctrine of abuse of minority.Footnote 69 This doctrine suggests that minority shareholders may incur civil liability when they exercise their voting power to prevent a project necessary to the corporation's business and success.Footnote 70 Imposing similar loyalty duties on minority shareholders to those of controlling shareholders also implies that the duty of loyalty in the civil law is just an extended expression of the general duty of good faith stemming from the law of obligations.Footnote 71

2. The cultural norms of corporate governance systems

This section is devoted to exploring how the fundamental non-formal norms of corporate governance in the Anglo-American and civil legal systems explain the transatlantic divergence of doctrinal views regarding controlling shareholders’ duties. Specifically, I show that the development of those regulatory approaches is highly associated with the cultural controversy on corporate purpose and the division of powers between managements, shareholders and stakeholders.Footnote 72 In a nutshell, the shareholder primacy model suggests that the company's decision-making process should assign first priority to the interests of shareholders relative to all other corporate stakeholders and those interests must exclusively govern the conduct of executives and directors.Footnote 73 In contrast, the stakeholders primacy model provides that the company and its organs must promote the interests of all corporate participants, including shareholders, customers, employees, suppliers, and communities alike.Footnote 74 Consequently, the difference in the dominant norms of corporate governance affects the manner in which the loyalty duty of controlling shareholders is designed. In particular, when extended protection is afforded to shareholders’ interests by a specific legal system, further powerful doctrinal measures are required to limit the ability of those shareholders to advance their interests at the expense of the company's well-being.

(a) Reconsidering the global debate on shareholder primacy versus stakeholder capitalism

The fundamental debate regarding the cultural norms that should govern the conduct of a company's insiders is often characterised as one between those who argue that management should focus primarily on advancing the interests of shareholders, and others who favour considering also the interests of a wider group of stakeholders as part of the decision-making process.Footnote 75 The shareholder primacy model justifies assigning priority to shareholders’ interests because it is a manifestation of an ‘ideal’ nexus of contract that most participants would adopt,Footnote 76 saving the participants from the transaction costs of developing such understandings on their own.Footnote 77 In addition, the contracts between the company and various stakeholders detail precisely the rights and obligations of the parties and thus there is no justification for imposing additional duties on insiders outside the framework of contractual provisions. Accordingly, the ‘fiduciary duties owed to shareholders are the only gap-filling device available to protect shareholders’ investments, whereas other claimants enjoy the gap-filling that courts routinely supply when interpreting the terms of their contracts with the firm’.Footnote 78 Thus, the contracts between the company and stakeholders are remarkably different from the agreements between the company and shareholders who are entitled to returns against their investments only after stakeholders’ contractual demands are satisfied.Footnote 79 As shareholders are considered to be the corporate residual claimants,Footnote 80 maximising their returns will enable the fulfilment of the contractual obligations towards all other constituents.Footnote 81

Nevertheless, those arguments involve several difficulties. For instance, the contractarian argument that describes the preferences of hypothetical stakeholders does not necessarily reflect the preferences of real constituents regarding the actual governance norm that should direct the activities of the company and its insiders’ conduct.Footnote 82 Hence, we cannot easily identify agreements between shareholders or stakeholders and management which explicitly require them to advance primarily shareholders’ interests.Footnote 83 Moreover, the perception that shareholders are the sole residual claimants in the firm is an additional inaccurate description of the relationship between various participants and the company. Because corporations are separate and independent legal persons the profits and assets are the property of the company entity and are not the property of shareholders.Footnote 84 Also, similar to shareholders, the value of stakeholders’ demands is heavily affected by many business resolutions that the company makes along its lifecycle. For instance, the occupational stability of employees who provide human capital to the company is dependent on the firm's performance and its financial results.Footnote 85 This is especially prevalent when the relationship between the company and employees is characterised by investment idiosyncrasy.Footnote 86 Under such a pattern, the company may induce stakeholders to invest specialised capital which cannot be traded at the same value elsewhere. As a result, stakeholders are regarded as being effectively ‘locked into’ the company's operations and prone to be damaged by the opportunistic behaviours of insiders.Footnote 87

Other scholars argue that even proponents of shareholder primacy should accept the proposition that shareholders should not necessarily pursue maximisation of profits exclusively.Footnote 88 Since shareholders may have social preferences besides maximisation of profits, their welfare would be maximised only if those preferences were also considered by management and the board of directors.Footnote 89 Thus, maximisation of shareholder welfare may involve the promotion of social objectives at the expense of profits.Footnote 90 Recent evidence suggest that shareholders rather than management are the parties who advocate progressive values, such as environmental and social agendas.Footnote 91

Considering the problematic assumptions of the traditional shareholder primacy model, many have embraced the stakeholder approach, which calls for the board of directors to directly address the interests of different stakeholders beside those of the shareholders.Footnote 92 Under this pluralist view, ‘the board must act in the interest of the company and its enterprise, understood as acting in the interest of all stakeholders and to a more or less clear extent including an interest of the enterprise in itself’.Footnote 93 Accordingly, several authors have suggested allocating board seats to a broader group of stakeholders, primarily employees,Footnote 94 as means of mitigating agency costs in corporations.Footnote 95 Others have proposed to extend the fiduciary duty of board members beyond shareholders to encompass a wider constituency of stakeholders, such as consumers and suppliers.Footnote 96

In August 2019, the Business Roundtable which includes the CEOs of nearly 200 major US companies released a statement advancing the stakeholder idea.Footnote 97 According to this statement, corporations should protect not only shareholders’ interests, but also those of employees, suppliers, and community members in general.Footnote 98 The Business Roundtable statement (BRT statement) prompted a lengthy commentary from legal scholars and practitioners, who discussed whether the statement indicated a dramatic shift in the cultural governance norm of the American law of corporations.Footnote 99 For example, Lucian Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita argued that there are conceptual difficulties with implementing pluralistic stakeholder theory because there is no clear guidance on how to aggregate or balance the interests of different constituencies in the face of trade-offs between the interests of stakeholders and long-term shareholder value.Footnote 100 Moreover, adopting stakeholder theory would be detrimental to shareholders, stakeholders, and society because it will protect corporate leaders from the pressures of hedge fund activists and institutional investors and make them less accountable.Footnote 101 As a result, those leaders could easily promote their private interests at the expense of shareholders and the economy more widely. Therefore, they concluded that the BRT statement was mostly a rhetorical public relations exercise rather than an expression of a meaningful change.Footnote 102

A radically opposite view was proposed in the UK by Oxford University Professor Colin Mayer in his famous book, Prosperity: Better Business Makes the Greater Good (2018). Mayer rejects the idea that ‘the purpose of business is exclusively to make money for the owners of the business, while sticking to the letter of the law and the spirit of social conventions’.Footnote 103 Instead, ‘the corporation should be reconsidered for what it is – a rich mosaic of different purposes and values’.Footnote 104 The traditional view that constrains the firm to a single narrow objective resulted in vast economic, environmental, political, and social damages.Footnote 105

Nevertheless, he rejects the view that regulation is an appropriate response to firm misbehaviour.Footnote 106 Rather, private ordering should be employed to include in the corporate contract a specific purpose which refers to stakeholders and general social interests beyond maximising shareholders’ value.Footnote 107 In Mayer's opinion, ‘enlightened corporations’ balance and integrate six components of capital that involve business activities: human, intellectual, material, natural, social, and financial capital’.Footnote 108 Accordingly, directors have a fiduciary duty to maintain those public purposes and ‘if they fail to do so then shareholders can seek injunctive relief to prevent them abusing the corporation's purposes’.Footnote 109 A recent large EU report adopts similar views to those of Mayer and suggests that possible future EU action in the area of company law and corporate governance should pursue the general objective of fostering more sustainable corporate governance and contributing to more accountability for companies’ boards of directors for sustainable value creation.Footnote 110 As will be clarified below, the different approaches regarding the importance that should be assigned in the company's decision-making process to the interests of shareholders on the one hand and stakeholders on the other hand, have a direct impact on the doctrinal design of the controlling shareholders’ duty of loyalty.

(b) The cultural norm of corporate governance and controlling shareholders’ fiduciary duty

In this part, I want to demonstrate that the doctrinal choice regarding controlling shareholders’ loyalty obligation is derived from the magnitude of protection given to shareholders’ interests in a given legal system. In principle, we can distinguish between three approaches in comparative corporate governance regarding the primary purpose of the corporation.Footnote 111 According to Delaware law, the primary purpose of the corporation is to make profits for shareholders.Footnote 112 Thus, management should put shareholders and their returns first, and avoid considering the interests of other corporate constituencies, such as creditors, suppliers, customers, employees, and the communities in which the company operates.Footnote 113

UK law affords considerable protection to stakeholders’ interests by obligating directors to act in good faith, in a manner that will promote the success of the company for the benefit of shareholders.Footnote 114 Directors are required to have regard to several factors when doing this, including the interests of various stakeholders, such as employees and customers.Footnote 115 While Enlightened Shareholder Value (ESV) does not embrace stakeholder theory (ie a company should be run in the best interests of all of its stakeholders) it certainly does consider their interests as a means to promoting the company's wellbeing. Thus, ‘whilst ESV does not oblige directors to act on the basis of stakeholder interests, it nonetheless endorses a multi-stakeholder decision-making rule and makes management at least indirectly accountable to stakeholders’.Footnote 116

The civil legal systems have adopted the stakeholder theory, under which the company's interests are not limited to those of shareholders and they encompass also the interests of creditors, employees, consumers, and society as well.Footnote 117 German corporate governance is considered to be a prototype of stakeholder orientation.Footnote 118 This is also manifested by the employee co-determination regime, which reserves up to half the seats on the supervisory board of listed firms for employees and union representatives.Footnote 119 As a result, employees have a significant voice in monitoring and advising relevant strategic and governance resolutions.Footnote 120

These three views of the goal of corporations postulate distinctive protection to the interests of shareholders vis-à-vis the interests of the stakeholders and how the wellbeing of the company should be perceived, considering the interests of different constituencies.Footnote 121 Moreover, these approaches correspond to the scale of loyalty obligations imposed on controlling shareholders towards the company and fellow shareholders. Accordingly, the larger the protection provided to shareholders’ interests in a given legal system, the more profound is the inclination to assign an equitable fiduciary quality to the loyalty duties of a controlling shareholder.

For instance, since the United States provides rigorous protection to shareholders’ interests, there is a concern that such protection combined with control devices will be employed by controlling shareholders to unduly accrue private benefit at the expense of minority shareholders and the company. In particular, because shareholder primacy calls for providing a preference for shareholders’ interests and entrusting them with further decision rights over different business resolutions,Footnote 122 broad authority coupled with ownership structures that secure shareholders’ control can impair the minority shareholders’ and the company's interests as a separate legal entity. For example, the United States adopts a permissive approach to dual-class shares structures that allows for a ‘wedge’ to be formed between a company's cashflows and voting rights.Footnote 123 Accordingly, founders can maintain such voting control of the company and its board without owning a majority of the company's common stock outstanding. Thus, enlarging shareholders’ rights and assigning them additional authority over the decision-making process of the business could have adverse outcomes when such powers are carried out under ownership devices that entrench controlling shareholders or founders.

To tackle this concern, the American legal system has designed loyalty obligations under the framework of the fiduciary relationship which subordinate the interests of controlling shareholders to those of the company.Footnote 124 At this stage, one could argue that the causal link between shareholders’ primacy and the extent and nature of loyalty obligations of a controlling shareholder could be satisfied only empirically. I acknowledge this criticism. However, if we accept the assumption that shareholder primacy involves assigning additional powers to all shareholders indifferently, the main issue that is left to be explored empirically, ceteris paribus, is whether concentrated ownership structure, as such, involves expropriation of minority shareholders’ rights.Footnote 125

In contrast, the UK provides some protection to stakeholders’ interests as part of the core obligation of company's organs to formulate and advance company wellbeing and shareholder value.Footnote 126 Since the cultural norm of the English corporate governance system deviates from providing sole protection to shareholders’ interests, the conduct obligations imposed on controlling shareholders are to some extent less restricting. Thus, rather than imposing an ex ante fiduciary obligation on controlling shareholders, English law ensures fairness between shareholders by subjecting controlling shareholders’ conduct to ex post equitable judicial review.

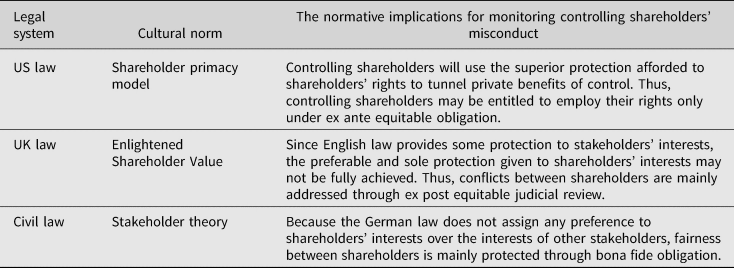

Lastly, German law has adopted the stakeholder theory, which identifies the benefit of the company with the aggregate interests of all stakeholders involved in its operation.Footnote 127 Under this framework, the law does not assign any superior protection to shareholders’ interests in relation to the interests of other stakeholders, and the company's welfare as a separate legal entity incorporates the interests of creditors, employees, consumers, and society as well. Since the interests of controlling shareholders are not given preferable protection in relation to the interests of other constituents, there is no normative justification to subject the relationship between shareholders to the traditional (and far-reaching) common law fiduciary setting. The following chart describes the association between the cultural norm and the scale of loyalty obligations.

Table 1. The cultural norms of corporate governance systems and the scale of controlling shareholders’ loyalty obligations

3. The historical development of the law of business groups

In this part, I argue that the doctrinal design of controlling shareholders’ loyalty obligations is related to the historical development of the law of business groups (BGs) in various legal systems. Specifically, I hypothesise that the formal legislative arrangements of BGs’ activities and the court-made loyalty obligations of controlling shareholders are considered to be alternative strategies for policing potential misconduct.

(a) The theoretical background of business groups

BGs are multi-business entities whose structure is described as ‘an economic coordination mechanism in which legally independent companies, bound together with formal and informal ties, utilise collaborative arrangements to enhance their collective economic welfare’.Footnote 128 BGs are a set of legally independent firms, operating in multiple industries, whose economic activity is controlled and coordinated thorough equity investments, superior controlling rights, and interlocking directorates.Footnote 129 The extensive management studies on the phenomenon of BGs has identified two major (and opposite) implications for firm performance and national economic development.Footnote 130

From an institutional perspective, BGs emerge as an efficient internal organisational form to inefficient or missing external market by using capital, labour and managerial markets to create and grow effective affiliates.Footnote 131 BGs are formed to fill voids in the infrastructures provided by the markets and to allow purchasing resources that would be unobtainable thorough arm's length contracting.Footnote 132 Further, companies that are included in a BG may enjoy superior competitive capabilities and can raise capital more quickly, especially in times of financial distress.Footnote 133 As a result, BGs will be prevalent as long as the market and other institutions are weak.Footnote 134 However, when market-based transactions become increasingly efficient and cheaper providers of required resources are common, BGs will tend to dissolve.Footnote 135

From an entrenchment perspective, the pyramidal structure of BGs can increase the agency costs between controlling and minority shareholders. This conclusion is based on several arguments.Footnote 136 First, the pyramidal structure allows controlling shareholders to control a significant number of firms with relatively small investment of equity thereby reinforcing the separation between ownership and control. Thus, owners can secure control rights without holding commensurate cash flow rights.Footnote 137 Secondly, controlling shareholders can reinforce their political influence relative to their actual wealth, and use their networks to restrict competition, and gain monopoly control over critical resources and sectors.Footnote 138 Thirdly, the ownership structure of BGs, which is depicted by small cash flow rights and large controlling rights, provides owners with the incentive to tunnel funds out of subsidiaries and into firms near the pyramid's apex – or even into their personal pockets.Footnote 139 Tunnelling by owners of BGs is carried out by shifting value between controlled firms via transfer pricing, the stipulation of capital at unreal prices; or via inflated payments for intangibles assets.Footnote 140 Furthermore, very often in groups, there is a central cash management where the funds of the subsidiaries are pooled.Footnote 141 Owners may transfer money from the resources pool to projects which may yield them significant profits at the expense of other projects that primarily improve the welfare of minority shareholders.Footnote 142 Fourthly, the ownership features of BGs expose creditors and other stakeholders of the subsidiaries to the opportunism of controlling shareholders mainly due to their small incentive to act in the sole interest of the subsidiary, by considering his interests in other companies in the group.Footnote 143 Lastly, the concentration of power in the hands of a few rent-seeking owners who extract value from minority shareholders and stakeholders may have negative consequences for national economic development and growth.Footnote 144

(b) The rise and fall of business groups in various jurisdictions

As previously discussed, the emergence of BGs is related to the immaturity of markets and institutions which provide established firms with ‘free cash flow in intra-group capital markets to exploit product-market opportunities’.Footnote 145 However, as market and economic institutions mature, BGs complete their positive role and their negative effects become more apparent. Thus, the pendulum movement between BGs’ positive and negative effects on economic development corresponds to their historical prevalence in different countries.Footnote 146 The rise of BGs in several western countries is associated with the industrialising economies experienced in the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries. At that time, BGs enhanced their technological abilities by establishing research and development plants and marketing new products and processes. These enterprises were supported by banking institutions, who injected the debt or equity finance required for those industries to flourish.Footnote 147 For instance, from the start of the German Industrial Revolution in the mid-nineteenth century, banks supported manufacturing and railway companies by taking an active part in the ownership and control of commercial corporations and overseeing the financial aspects of their activities.Footnote 148 By owning a substantial part of the cash flow rights in addition to providing operating credits, universal banks had a decisive say in how those business should be managed, and the banks themselves became BGs.Footnote 149

Another pattern that supports the prevalence of BGs in the German economy is the concept of ‘Deutschland AG’ which refers to the close cooperation between various corporations in different economic sectors – to the extent that in some instances these corporations appeared to be different arms of a single company.Footnote 150 This was also expressed in the network of cross-ownership between the large banks and commercial companies which, at its peak, involved of more than 168 different cross-ownership connections between the hundred largest corporations in Germany.Footnote 151 Therefore, the German economy has operated as one particularly large corporation with mutual cooperation and supervision that allowed it to grow over time.Footnote 152 However, in the 1990s central banks in Germany suffered a severe crisis following the entry of international competitors into the national banking system.Footnote 153 In response, many financial institutions decided to diversify their portfolio by reducing their holdings in the share capital of German corporations.Footnote 154 These developments have to some extent moderated the dominance of the concept of ‘Deutschland AG’ in Germany.Footnote 155 Nevertheless, other forms of BGs, such as those owned and controlled by elite families or the state are still prevalent. Specifically, a number of German entrepreneurial families hold numerous enterprises through a holding-company type of BG.Footnote 156 One of the most well-known examples of family-owned BGs with prominent influence on the German economy is the Porsche-Piëch family, which controls the Porsche Automobil Holding SE. The latter is the controlling shareholder of the Volkswagen Group.Footnote 157 Moreover, a number of BGs, such as Preussag, Veba, and Viag were established by the state at the beginning of twentieth century to engage in mining, glassmaking, transport facilities, and the distribution of energy and were eventually privatised during the neo-liberalism wave of 1990s.Footnote 158

In the United States, BGs existed as early as the turn of the twentieth century and became a common corporate form between 1930 and 1940, mostly in public utilities (eg electricity, gas and transportation) and in manufacturing.Footnote 159 In the last third of the nineteenth century, the US economy encountered a notable industrial transformation that involved significant technological changes, such as the introduction of electric power, which produced a variety of business opportunities. These changes created a transformation in corporate structure, which resulted in many industries, such as transportation and chemicals, becoming dominated by a small number of massive centrally-controlled enterprises.Footnote 160 Moreover, even in the United States, significant parts of BGs were owned and controlled by major investment banks such as Morgan, who were involved in directing the financial and strategic aspects of the industrial enterprises’ operations. This ownership structure was further reinforced in the 1920s when the presidential administration advanced the ideology of the free market and enacted the Revenue Act of 1918. This Act provided an incentive for the increase in the number of holding companies and BGs because it made inter-corporate dividends fully tax-deductible.Footnote 161 However, between the 1940s and early 1950s, comprehensive regulation was adopted, with the aim of eliminating BGS as an ownership structure, as they were perceived to damage competition in the national economy. Legal reforms in the fields of infrastructure, taxation and protection of investors allowed the removal of the concentrated ownership structure and the adoption of a diffuse one. As explained by Kandel, et al:

Until the middle of the 20th century, business groups, often pyramidal in structure, were as important in the United States as they are in present-day emerging markets. Their decline began in the second half of the 1930s and gathered force in the 1940s following a sequence of reforms, some of which explicitly targeting the groups, perceived as wielding excessive economic and political influence. We posit that an array of reforms, not a single silver bullet, combined with a long-term shift in U.S. politics, ultimately brought about the demise of U.S. business groups.Footnote 162 (emphasis added)

In contrast, in Britain, the pattern of BGs owned and controlled by the banking system was not part of the early industrialisation processes and the capital demands of the industry were mainly fulfilled through ‘re-invested profits, stock market issues, private placements with stockbrokers and insurance companies, and family’.Footnote 163 Accordingly, Britain's domestic banking system did not provide adequate drivers for forming domestic BGs and instead focused on the provision of short-term finance. Thus, BGs as an organisational form were found much less frequently in British domestic business.Footnote 164 Nevertheless, British firms established BGs in colonial territories or post-colonial countries, utilising the underdeveloped product markets in those economies with the support of capital markets in London.Footnote 165 These BGs have gradually declined due to changes in the political environment in those foreign countries and changes of perception in British capital markets, which became hostile to this phenomenon.Footnote 166 After World War II, and especially between the 1970s and 1990s, large diversified conglomerates began to flourish. Their growth is mainly attributed to the fluid market for corporate control that encouraged a range of funding opportunities for acquisitions and sell-offs of enterprises. However, since the 1990s, the British economy has witnessed a decline of those conglomerates due to market pressures to refocus on a narrow range of products or markets rather than creating diversified international businesses.Footnote 167

As will be illustrated below, the present persistence of family and state-owned BGs in Germany, alongside the diminishing prevalence of them in the United States (and their complete absence in the UK) is compatible with current legal arrangements that specifically address the unique agency conflicts in such ownership structures. Consequently, in countries where there is a particular normative framework for regulating these conflicts in the BGs setting, there is no need to subject owners to obligations derived from fiduciary law.

(c) Regulatory models of business groups and controlling shareholders’ fiduciary duty

Since BGs involve special agency conflicts, several civil law countries regulate the relationship between controlling shareholders and the group's subsidiaries through a distinctive branch of law, known as the ‘law of groups’.Footnote 168 German jurisprudence recognised a special ‘group law’ (Organschaft) more than a century ago,Footnote 169 and in 1965 it was formally codified in the Stock Corporation Act (AktG). The main motivation behind the 1965 codification was to protect minority shareholders and creditors of controlled subsidiaries from the dangers inherent in the exertion of control by majority shareholders, whilst also preserving the ownership structure of BGs.Footnote 170 The normative regimes of BGs distinguish between contractual groups (Vertragskonzern) and de facto groups (Faktischer Konzern).Footnote 171 Under the contractual groups’ scheme, parent and subsidiary companies engage in a formal group agreement. This agreement enables the parent to influence the subsidiary's management, even in cases when it damages the subsidiary's interests. However, the agreement obligates the parent to account annually for the subsidiary's losses.Footnote 172 If the control connection between those entities does not involve a group agreement, the rules on de facto groups will apply. Accordingly, the parent company is not allowed to intervene in the subsidiary's management, unless the parent compensates for subsidiary's specific losses. General liability provisions and disclosure obligations accompany these rules.Footnote 173 In addition, the law of groups regulates related party transactions between the controlling shareholder and the subsidiary companies by subjecting them to an audited ‘dependency report’ as well as to rigorous liability rules for the controller and for directors. Accordingly, the executive board is required to submit to the supervisory board a special report that details all transactions between the subsidiary and the parent company or other companies in the BG – including all transactions initiated by the controlling shareholder that are in his interests. This report must be audited both by independent accountants and the supervisory board, who are required to submit their assessments at the shareholders’ general meeting.Footnote 174

In contrast, the Anglo-American legal system has relied on traditional corporate law mechanisms to regulate the relationship between controlling and minority shareholders.Footnote 175 Because there was no special branch of law devoted to curbing the potential misbehaviour of controlling shareholders in the context of BGs, agency conflicts were generally addressed in a manner similar to independent (one-tier) corporations.Footnote 176 Hence, since the beginning of the twentieth century, United States courts and prominent academic scholars have advanced the idea that powers granted to ‘any group within the corporation, whether derived from statute or charter or both, are necessarily and at all times exercisable only for the rateable benefit of all the shareholders as their interest appears’.Footnote 177 This view is nicely formulated in the early ruling of Jones v Missouri-Edison Electric Co.Footnote 178 In this case, the controlling shareholders of Corporation A owned all the stock of Corporation B. They voted for the merger of the two corporations to form Corporation C, based on grossly inequitable consideration for the minority stockholders of Corporation A. The minority shareholders of Corporation A initiated a derivative action and sought the dissolution of Corporation C and an accounting of all property owned by Corporation A in the hands of Corporation C. The court determined that the action of the controlling shareholder had been a fraud upon the minority stockholders, but Corporation A ‘was not so irrevocably dissolved that its rehabilitation is beyond the power of a court of chancery’.Footnote 179 The court of chancery maintained as follows:

A combination of the holders of a majority or of three-fifths of the stock of a corporation to elect directors… constitutes them actual, if not technical trustees for the holders of the minority of the stock…Any sale of the corporate property to themselves, any disposition by them of the corporation or of its property to deprive the minority holders of their just share of it or to get gain for themselves at the expense of the holders of the minority of the stock, becomes a breach of duty and a trust which invokes plenary relief from a court of chancery. Footnote 180 (emphasis added)

Moreover, the courts clarified the content of the fiduciary obligation imposed on controlling shareholder and stated that he is ‘bound to be wholeheartedly, earnestly and honestly faithful to his corporation and its best interests; his own selfish interests must be ignored’.Footnote 181 Thus, if the controlling shareholder votes ‘against the interest of his company, against the interest of the minority and in favor of his own interest, by such selfish action, by omission of fidelity to his own duty as a trustee, he forfeits approval in a court of equity’.Footnote 182 However, other rulings emphasised that only majority stockholders who do in fact direct the affairs of the corporation rather than just holding the power to appoint directors will be subjected to fiduciary duties.Footnote 183

These different legal strategies were designed because of dissimilar approaches to whether BGs were desirable for enhancing economic growth. Germany encouraged the formation of BGs because of efficiency considerations related to vertical integration of the value chain required to control quality and internalise profit.Footnote 184 While at the corporate level, such an ownership structure allows the reduction of costs by combining the entire manufacturing chain under one united frame,Footnote 185 at the shareholder level, it may involve risks to minority owners and creditors who are exposed to potential misappropriation of resources by controlling shareholders.Footnote 186 Thus, to maintain the wellbeing of shareholders and corporations integrated in the BGs’ organisational structure, formal detailed rules were required. In addition, considering the pervasiveness of these entities (especially until the 1990s) in the German economy, merely subjecting controlling shareholders to conduct standards derived from fiduciary law will not capture the complexity of managing subsidiaries’ businesses as well as shareholder relationships under such an ownership structure.

In contrast, the United States embraced a different approach regarding the attractiveness of BGs in the national economy. In particular, jurists and policymakers were motivated to eliminate this ownership structure because of its severe consequences for economic growth. As a result, significant reforms were implemented to disincentivise entrepreneurs from incorporating business activities through the organisational structure of BGs.Footnote 187 For example, the Investment Company Act (ICA) of 1940 affected holding companies by subjecting them to regulation as closed-end mutual funds unless their ownership stakes in the firms they controlled exceeded 50%. The ICA imposed important constraints on the controlling shareholder's involvement in decision-making in the subsidiaries of BGs, and mandated detailed disclosure obligations.Footnote 188 Consequently, the ‘ICA would force the controlling shareholder to become a passive investor in her corporate empire’.Footnote 189

Between the 1940s and the 1950s, court rulings extended the traditional fiduciary duty imposed on controlling shareholders towards minority shareholders in independent corporations to majority shareholders of a parent company in its relationship with the minority shareholders of the subsidiary, thereby creating an additional chilling effect to maintaining BGs.Footnote 190 For instance, in the case of Mayflower Hotel Stockholders Protective Comm v Mayflower Hotel Corp,Footnote 191 minority shareholders of a subsidiary alleged that controlling shareholders sold their stock at a deliberately misrepresented price in order to decrease the price at which the minority could sell, as part of a conspiracy between the controlling shareholder and the purchaser. The Court of Appeals ruled that the relations between a parent company and its subsidiary are subject to a ‘strictest account and to the observance of the highest rectitude’.Footnote 192 Accordingly:

While the question in some of the cases cited arose between stockholders and the directors and officers of a company who, as such, held a position of trust as to the former, still where, as in this case, a majority of the stock is owned by a corporation or a combination of individuals, and it assumes the control of another company's business and affairs through its control of the officers and directors of the corporation, it would seem that, for all practical purposes, it becomes the corporation of which it holds a majority of stock, and assumes the same trust relation towards the minority stockholders that a corporation itself usually bears to its stockholders.Footnote 193

When comparing the state of affairs in Germany and the United States to the position in the UK, it is not surprising that English law has not adopted fiduciary duties to curb the power of controlling shareholders. Since BGs have never been prevalent in the British domestic business,Footnote 194 there was no need to address the unique agency conflicts involved in this ownership structure by designing special regulatory responses. Consequently, English law has long adhered to the traditional common law rule that controlling shareholders will not be considered as fiduciaries.Footnote 195 The following chart describes the association between the historical development of BGs and the scale of loyalty obligations of controlling shareholders.

Table 2. The historical development of BGs and the scale of controlling shareholders’ loyalty obligations

4. The policy implications of the macro-level investigation

In the last two decades, corporate law scholars have debated whether we should expect a clear convergence of corporate governance norms across different jurisdictions. In a provocative paper, Hansmann and Kraakman announced the end of the familiar corporate history in the sense that no dispute is expected to arise in relation to maximising shareholders’ value exclusively rather than any interests of other stakeholders.Footnote 196 Almost two decades after their theory was presented, there is some evidence that civil legal systems have reinforced the protection afforded to the interests of shareholders, following the Anglo-American tradition (even if there are still significant differences in the way these protections have been implemented).Footnote 197 One clear example is the adoption of amendment provisions in the European Directive on the Rights of Shareholders.Footnote 198 The stated purpose of the amendment provisions is to promote effective engagement of the shareholders in relation to the decision-making process in the company by improving the flow of information from the company to its shareholders. In addition, the amendment increased the oversight of remuneration paid to directors and subjected the validity of related party transactions to detailed approval mechanisms.Footnote 199 The global embracing of say-on-pay arrangements, even in civil law countries in which it can be usually assumed that the controlling shareholder has incentives to effectively monitor remuneration paid to executives, also indicates a move towards shareholder-centric thinking.Footnote 200 The strengthening of shareholder rights in respect of companies’ decision-making processes may ‘encourage investor interest in pan-European equity markets, therefore contributing to the much-needed European initiative to develop deep and liquid capital markets in order to provide corporate finance’.Footnote 201

The macro-level investigation of the fiduciary duties of controlling shareholders discussed in the previous parts of this study has taught us that the doctrinal choices made by different legal systems are very often the result of a unique cultural environment and changes in business history. This implies that jurists and policymakers should be careful before they decide to adopt doctrinal choices in different parts of corporate governance that will result in a global convergence of legal norms. Moreover, and essentially, the traditional doctrinal design created by a particular jurisdiction in certain areas of corporate law cannot be isolated from the broad cultural and sociological framework in which companies make business, which is subjected to national law and regulation. As the ‘rules of the game’ for regulating the relationship between insiders and outsiders are the product of delicate cultural and historical equilibrium, introducing imported arrangements from other jurisdictions may distort the specific balance that is in place and it may require significant additional modifications in other areas of law in order to restore the previous stability. In addition, since the design of any corporate governance rule is a product of a special historical evolutionary process, automatic implementation of foreign arrangements will not fit with the unique socio-economic conditions of a given legal system.

This observation is supported by empirical evidence as well. For example, a study by Black et al examined which corporate governance practices predict a higher firm value in Brazil, India, Korea, and Turkey.Footnote 202 Black et al constructed overall country-specific governance catalogues, comprised of indices for disclosure, board structure, ownership structure, shareholder rights, board procedure, and control of related party transactions. Their study reveals that board structure is a predictive firm value in Brazil, Korea, but not in India and Turkey. In addition, while board independence predicts market value in Brazil, Korea, and Turkey, there is weaker evidence that board committees can predict value. Once controls have been made for the effect of disclosure and board structure, there is no evidence that the other indices, such as board procedure, shareholder rights, ownership structure, and related-party transactions, predict a firm's value, either individually or together.Footnote 203 These results indicate that governance arrangements that are generally perceived as optimal for investor protection in one country may be suboptimal in another, once the institutional, political, economic and cultural environment of each country has been considered. Therefore, any national reform that aims to mechanically import corporate governance norms that were designed in other jurisdictions may impair the gradual establishment of national legal doctrines that are a result of cultural and historical processes.Footnote 204

Conclusions

This paper was devoted to exploring the similarities and discrepancies in regulating the conduct of controlling shareholders by employing a macro-level analysis of cultural and business historical developments in different legal systems. Our main contributions can be summarised as follows:

(1) The extent of controlling shareholders loyalty and care obligations imposed by a particular legal system is a result of the scope of protection provided to shareholders’ interests by the cultural norms of that country's corporate governance systems.

(2) The doctrinal design of controlling shareholders’ duties corresponds to the historical development of the law of BGs. Accordingly, formal legislative arrangements of BGs operations and court-made loyalty obligations are considered to be alternative methods for monitoring potential mischief.

(3) Comprehensive initiatives to converge corporate law and governance across nations should be carried out with caution, because they can undermine the normative equilibrium that exists in a given jurisdiction.