Introduction

Much has been written about the politics of social policy retrenchment and restructuring since the publication of Paul Pierson's book Dismantling the Welfare State? in 1994 (Pierson, Reference Pierson1994). A central aspect of this literature concerns how self-reinforcing policy feedback from existing social policies have complicated efforts by right-wing governments to launch successful attempts at retrenching and restructuring social programming and welfare state spending. Comparative welfare state research has generally focused on the protagonists of welfare state expansion—left-wing parties—while neglecting the purported antagonists of the welfare state, right-wing parties (Jensen, Reference Jensen2014). In this article, we draw on the concept of policy feedback and related analytical tools from the relevant policy and political science literature to address the following puzzle: How do political parties located on the right of the political spectrum adapt to electoral constrains and global crises affecting the welfare state?

To answer this question, we turn to the politics of social policy in the province of Quebec, which has the highest level of social spending in Canada and features social democratic elements absent from the other jurisdictions of a country typically classified as a low social-spending liberal welfare regime (Bernard and Saint-Arnaud, Reference Bernard and Sébastien2004; van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, Plante, Raiq, Proulx and Faustmann2017). More specifically, focusing on three policy areas, we analyze the politics of social policy in Quebec under the centre-right Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) government (2018–) both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. We show that the CAQ, despite its right-wing identity, preserved and expanded key elements of the welfare state since its election in 2018.

We explore the reasons that have pushed the CAQ to favour a centrist social policy agenda. We suggest that existing policy legacies stemming from self-reinforcing effects combined with negative popular reactions to previous retrenchment contributed to the CAQ government embracing a more centrist electoral strategy than its right-wing identity would suggest. By appealing to the median voter through a rejection of welfare retrenchment—and even expansion in some policy areas—the CAQ indicated a departure from the austerity measures imposed by the previous Liberal government, thereby increasing its electoral appeal and allowing CAQ leader François Legault to depict himself as a “pragmatist” (Latraverse, Reference Latraverse2018).

Three main sections constitute the remainder of this article. In the first section, we discuss the literature on policy feedback and welfare state reform in order to outline the framework that guides the empirical analysis and then briefly discuss case selection and our methodological approach. In the second section, we discuss the evolution of the general fiscal policy framework during the CAQ's tenure and then review three policy areas: income support, childcare and early childhood education, and long-term care. These cases have been selected because they represent a wide range of social policy sectors associated with core and salient electoral promises made by the CAQ. In the last main section, we directly compare these policy areas, considering the theoretical framework, before offering general conclusions and highlighting the limits of the study.

Background, Puzzle and Framework

In Quebec, the CAQ is widely perceived as a right-of-centre political party tied to the conservative movement (Boily, Reference Boily2018). As its name suggests (“Coalition for Quebec's Future”), the CAQ is a coalition of Quebec nationalists and is the heir of the Action démocratique du Québec (ADQ), a party it merged with in 2012. The ADQ was a right-wing nationalist party that advocated for health care privatization, personal responsibility, major tax cuts, and welfare state retrenchment. Since its creation, the CAQ has also gathered businesspeople (including leader François Legault) and politicians previously associated with the Conservative Party of Canada (CPC), including Finance Minister Eric Girard. The CAQ formed the government after winning the 2018 provincial elections handily (74 seats out of 125 in Quebec's National Assembly). Its popularity remains particularly strong, as evidenced by its re-election in 2022 with 90 seats.

On two cleavages that divide the Quebec electorate—the role of the state in the economy and the management of ethno-cultural diversity—CAQ supporters tend to be more on the right of the political spectrum than the electorate of other parties. Moreover, at each provincial election from 2012 to 2018, the probability that a citizen voted for the CAQ was considerably higher for respondents on the right on these two dimensions, which suggests that the party's positions reflected their preferences (Bélanger and Godbout, Reference Bélanger and Godbout2022). This is partly why Quebec's labour unions reacted so negatively to the formation of a CAQ majority government, as they had strongly criticized the party's platform on issues such as the minimum wage, tax cuts and reducing the size of the province's public service (Lévesque, Reference Lévesque2018).

The CAQ is also a nationalist party that promotes secularism, additional protection for the French language, and greater provincial autonomy, while opposing the separation of Quebec from the rest of Canada. Particularistic positions on issues dealing with ethno-cultural diversity and a push to reduce immigration levels illustrate this political stance, a situation that has consolidated its image as a genuine right-wing party. In the 2018 election, the CAQ benefited from the fragmentation of the vote for the Parti Québécois (PQ), and whereas the CAQ appealed to conservative nationalist voters, progressive nationalists migrated to the left-wing party Québec solidaire.

Considering the above, one would expect that a CAQ-led government would have embraced and implemented social policy retrenchment. However, we show this is not the case. The question is how to explain the fact that despite its right-wing political identity, the CAQ government has preserved and even expanded key elements of the provincial welfare state. This study explores potential explanations and argues that the CAQ's behaviour can be better accounted for by policy feedback analysis in a way that is congruent with the median voter model.

A possible explanation for this situation is the fact that the “exogenous shock” (Pierson, Reference Pierson2000) of the COVID-19 pandemic, which hit Quebec particularly strongly starting in March 2020, forced the CAQ to expand social programming. There is ample evidence in the international policy literature that global crises such as COVID-19 can compel left- and right-wing governments to adopt expansionary social policy responses (Lipsmeyer, Reference Lipsmeyer2011; Jacques Reference Jacques2020). From this perspective, the COVID-19 crisis would have pushed the CAQ government to adopt expansive social policies to mitigate the negative economic and social impacts of the pandemic.

Our analysis rejects this potential explanation by showing that although the pandemic did push the CAQ government to increase social spending, both the party's 2018 electoral platform and its first two budgets, which preceded the pandemic, point to a rejection of welfare state retrenchment. We argue that this sequencing of decisions is important. In our view, the government's choices during a period of economic expansion are particularly revealing. During periods of expansion, governments have the room to manoeuvre to implement their preferred policies, leading to larger differences between the policy choices of the Left and the Right. Right-wing governments generally prefer to cut taxes, while left-wing governments tend to prioritize higher social spending. In contrast, during crises, differences in policy outputs between the Left and Right are smaller, as the Right must refrain from cutting taxes as popular demand for state protection grows, while the Left cannot easily expand expenditures because crises heighten fiscal pressures (Lipsmeyer, Reference Lipsmeyer2011; Jacques Reference Jacques2020). We argue that the fact that the CAQ refrained from tax cuts in the first two years of its mandate, which were characterized by an unparalleled period of economic expansion and an improved fiscal situation, is a particularly clear indicator of its reorientation toward the centre.

A key contributing factor to the CAQ's centrist social policy orientations before the pandemic is voters’ negative reactions to the austerity measures enacted by the provincial Liberal government of Philippe Couillard (2014–2018). Such measures triggered major street protests and strong criticisms from opposition politicians, a situation that did not prevent Premier Couillard from moving forward with his austerity agenda (Authier, Reference Authier2015). With looming elections in 2018, the Couillard government changed course and supported higher spending levels, but this inconsistent messaging reduced the vote intentions for the government (Montigny and Grégoire, Reference Montigny, Grégoire, Pétry and Birch2018). In reaction to this context, the CAQ decided to steer away from austerity to distinguish itself from Couillard's unpopular policies (Bélanger and Chassé, Reference Bélanger and Chassé2021).

Policy feedback theory helps to explain negative reactions to social policy austerity during the Couillard years and the CAQ's decision to move away from this type of policy agenda. Self-reinforcing policy feedback is a mechanism by which the endogenous features of a policy can gradually make it stronger (Jacobs and Weaver, Reference Jacobs and Kent Weaver2015). There are different types of self-reinforcing feedback effects, and here we focus on how existing policies create constituencies over time through greater public support, interest group formation and overall institutional stickiness. First, policies may stimulate the creation of vested interests both within and outside government. Second, policies can generate growing public support over time because of the sheer number of people who benefit from them and the fact citizens come to see them as necessary. Finally, existing policies can become institutionally sticky because the cost of replacing them is likely to increase over time, at least in the case of self-reinforcing dynamics. These realities are likely to make it harder for politicians to dismantle or even simply retrench such popular and well-entrenched policies (Pierson, Reference Pierson1994, Reference Pierson2000; Béland and Schlager, Reference Béland and Schlager2019).

In this paper, we provide evidence of how policy feedback theory sheds light on the CAQ's move toward the centre. Because Quebec has developed a particularly extensive provincial welfare state (van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, Plante, Raiq, Proulx and Faustmann2017), powerful vested interests associated with social programs such as public sector unions and civil society organizations have emerged in recent decades to support such programs (Béland and Lecours, Reference Béland and Lecours2008). Simultaneously, as our analysis suggests, there is evidence that residents of the province are attached to what is known as the Quebec Model of economic and social development, which emphasizes the primacy of higher public spending at the expense of tax cuts (Daigneault et al., Reference Daigneault, Birch, Béland and Bélanger2021). Our case studies provide some evidence that the CAQ adapted to this model by adopting policies that seem palatable to most voters, beyond the party's right-wing base.

While some may argue our puzzle can be solved by the concept of the median voter, we insist this is not an alternative to policy feedback analysis but an analytical tool compatible with it. In fact, the public's interaction with government programs shapes their beliefs and shifts their views (Béland and Schlager, Reference Béland and Schlager2019). Policy feedback research contends that citizens accustomed to a relatively generous welfare state, such as the Quebec Model, will either develop preferences in support of an even more encompassing welfare state or will at least prefer to maintain spending levels, as they cherish the current institutions (Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, Abrassart and Nezi2021). Consequently, it is possible that the Quebec Model shapes the long-term equilibrium of public opinion about preferred levels of spending and constrains government policy choices. Thus, the path to power, even for a right-wing government, features the preservation of the welfare state (Pierson, Reference Pierson1994; Jensen, Reference Jensen2014).

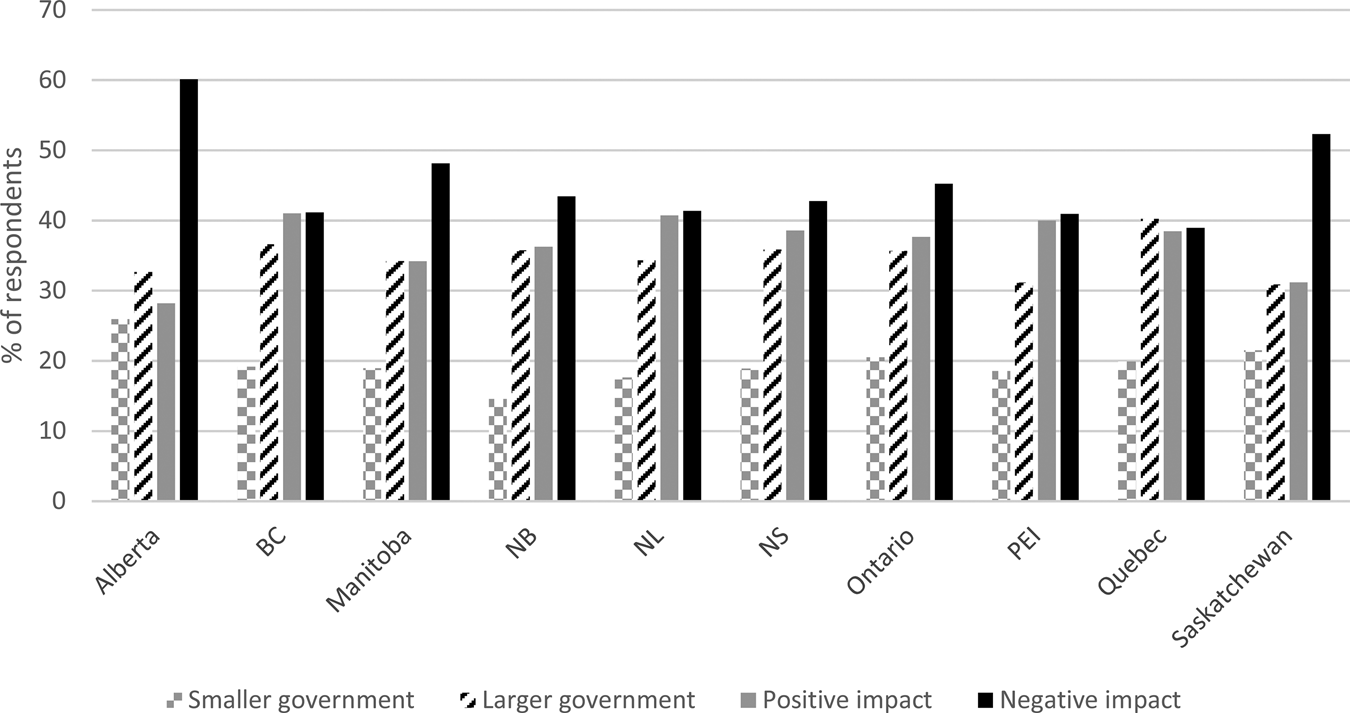

Unfortunately, there are very few publicly available surveys that compare support for provincial governments’ intervention in specific policy areas across provinces. To provide evidence of the leftward orientation of the median voter in Quebec, we use the Confederation of Tomorrow survey conducted annually by Environics over almost 5,000 respondents from 2019 to 2022 (Environics Institute, 2022). In contrast to most surveys asking similar questions, the Confederation of Tomorrow has large samples for each province, allowing us to compare Quebec with the others. We use two questions posed in the 2019, 2021 and 2022 surveys. The first asks whether respondents prefer a larger government with more services, a smaller government with fewer services, or neither in particular. The second asks whether the government has a positive or negative impact in respondents’ lives or whether it doesn't have much impact. Figure 1 reveals the distribution of answers in the 10 provinces, on average, for the three years (N ranges from 555 in Prince Edward Island to 2,758 in Ontario, with 2,666 valid answers in Quebec).

Figure 1. Average support by province for larger (smaller) government and average perception that government has a positive (negative) impact, Confederation of Tomorrow survey, 2019, 2021 and 2022

Quebec has the largest proportion of respondents who support a larger government with more services (40.25 per cent, against an average of 34.13 per cent outside Quebec). Quebec clearly has the smallest proportion of respondents who think the government has a negative impact on people's lives (38.96 per cent against an average of 46.17 per cent outside Quebec), and the proportion of respondents who think government's impact is positive is above average (38.5 per cent in contrast to 36.4 per cent). Hence, the CAQ government had to contend with an electorate that is comparatively more attached to government intervention than elsewhere in Canada.

This public opinion data is consistent with the historical and comparative research on the relationship between social policy and substate nationalism, which emphasizes how social programs, which are tied to the idea of national solidarity, have become an integral part of Quebec's identity and political culture since the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s (Béland and Lecours, Reference Béland and Lecours2008). The current existence of a strong political and ideological tie between Quebec's identity and social policy is evidenced in recent scholarship about the expansion of the Quebec Pension Plan, which suggests that generous social benefits remain a distinctive feature of that provincial and national identity (Béland and Weaver, Reference Béland and Kent Weaver2019).

In the following analysis, we discuss the impact of policy feedback effects as they relate to interest groups and public opinion, using a qualitative case study design that allows for a systematic comparison of three main policy areas within Quebec's provincial welfare state: income support, childcare, and long-term care. These areas were selected because they represent central components of the provincial welfare state. Generous income support, particularly for families, is a distinctive feature of the Quebec Model (Godbout and St-Cerny, Reference Godbout and St-Cerny2008), while childcare has long become a core aspect of Quebec's social programming, which is strongly shaped by social investment principles (van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, Plante, Raiq, Proulx and Faustmann2017; Arsenault et al. Reference Arsenault, Jacques and Maioni2018). We also study these policy areas because they proved central to the CAQ's electoral commitments. Indeed, “putting money back into families’ pockets,” which concerns income support as well as early childhood education and care, represents one of the two most important promises made by this government, according to the CAQ itself (the other was to eliminate the wealth gap between Quebec and Ontario) (Birch et al., Reference Birch, Dufresne, Duval, Tremblay-Antoine, Birch, Dufresne, Duval and Tremblay-Antoine2022). We study long-term care for older people for two reasons. First, it requires a stand-alone treatment in part because of its centrality during the pandemic. Second, it represents the only other social policy, excluding those concerning health care, considered to be an important promise both by the CAQ and by experts evaluating the salience of the CAQ's promises (Birch et al., Reference Birch, Dufresne, Duval, Tremblay-Antoine, Birch, Dufresne, Duval and Tremblay-Antoine2022). These three case studies are preceded by an analysis of the Quebec government's general fiscal framework, paying particular attention to health care expenditures, which is by far the largest source of public spending in the province.

In the following section, drawing on the 2018 CAQ platform, government documents, media stories, and public opinion data, we discuss each of the three policy areas in turn. To increase the analytical coherence of our case study approach, the discussion of each will begin with existing policy legacies, what happened during the Couillard years, what the CAQ stated in its 2018 platform, what measures were enacted during their first two budgets characterized by a period of economic expansion, and the impact of the pandemic on provincial social policy.

General Budget and Health Expenditures

Three main features characterize Quebec's budgetary framework. First, it maintains the highest levels of taxes and spending expressed as a proportion of gross domestic product (GDP) of any subnational jurisdiction in North America, which generates strong feedback effects (van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, Plante, Raiq, Proulx and Faustmann2017). Second, growing health care costs, which represent more than 40 per cent of program expenditures, generate structural pressures on the provincial budget and must be considered in this analysis of the CAQ's management of the general fiscal framework. Third, until 2020, Quebec maintained the highest public debt among Canadian provinces, despite having a balanced budget act since 1996. To force governments to adopt prudent fiscal management and to meet ambitious debt reduction goals, the Generations Fund was created in 2006. It compels governments to allocate a significant proportion of their expenditures to a wealth fund, which is invested in financial markets until it is used to repay public debt.

With a projected deficit increase to Can$7.6 billion in 2015 (7.9 per cent of total government expenditures) (Tellier, Reference Tellier, Pétry and Birch2018), the Quebec Liberal Party (QLP) government (2014–2018) implemented significant budget consolidation measures in the first two years of its mandate. The speed at which the structural adjustment took place surprised many experts, as the government limited the growth of expenditures to 1.4 per cent in 2014 and 1.1 per cent in 2015, well below cost inflation, and generated surpluses as early as 2016.

Although this fiscal consolidation put Quebec on a fiscally sustainable path, austerity has been identified as one of the decisive factors explaining the defeat of the Couillard government, as the government's disapproval jumped from 51 per cent in the fall of 2014 to 65 per cent in October 2017, and only a third of citizens approved of austerity (Bélanger and Chassé, Reference Bélanger and Chassé2021). Moreover, in its 2017–2018 budget, the government increased public expenditures by 6.5 per cent, a year before the election (Tellier, Reference Tellier, Pétry and Birch2018). This was viewed as pure electioneering by voters and pundits and contributed to a drop in the government's popularity (Montigny and Grégoire, Reference Montigny, Grégoire, Pétry and Birch2018).

As a centre-right party, the CAQ could have suggested reducing public spending to allow for tax cuts. Instead, during the 2018 election, the CAQ's platform criticized the previous government's austerity measures and refrained from proposing any further expenditure cuts, following a blame avoidance strategy (Weaver, Reference Weaver1986). The CAQ promised to maintain public services and increase health expenditures by 4.1 per cent annually. It also proposed ambitious increases in child transfers (see the section below on income support) while maintaining budgetary balance (CAQ, 2018a). Although the CAQ often laments the level of taxation in the province and has promised not to raise taxes, their commitment to maintain expenditure growth while balancing the budget prevented the party from proposing tax cuts beyond a marginal reduction of school taxes during their first term in office.

In government, the CAQ quickly realized that a 4.1 per cent health spending growth rate would be insufficient, considering the demand for reinvestments in health care after a period of austerity. Its first two budgets proposed an annual growth in health spending of 6.5 per cent and 5.3 per cent, respectively, and a 6 per cent annual overall increase in the province's total expenditures (Government of Quebec, 2020a). At the same time, tax revenues were stable from 2018 to 2020 at 38.8 per cent of GDP, which remains significantly above the Canadian provincial average of 33.5 per cent of GDP. The CAQ reduced school taxes, as promised, but the revenue losses were compensated by an increase in pension contributions (implemented by the previous government) as well as income and consumption tax revenue growth in a period of strong economic expansion (Gagné Dubé, Reference Gagné-Dubé2022).

The CAQ's first two budgets, implemented during a period of economic expansion (the March 2020 budget makes little reference to COVID-19), reveal that this government chose to move toward the centre by spending the surplus it inherited from its predecessor in additional expenditures, whereas a traditional right-wing government would be expected to cut taxes. Constrained by a balanced budget act and the large annual payments to the Generations Fund, as well as the growth of health care costs and citizens’ demands for additional investments in public services, the government had to refrain from tax cuts, instead pursuing significant increases in public expenditures even before the start of the pandemic.

After that, the “exogenous shock” (Pierson, Reference Pierson2000) of the pandemic pushed public expenditures even further upward, leading the Legault government to suspend the Balanced Budget Act (Dinan and Tellier, Reference Dinan, Tellier, Birch, Dufresne, Duval and Tremblay-Antoine2022). Although the federal government, led by Justin Trudeau and the Liberal Party of Canada, implemented most of the expensive COVID-related income support measures and increased transfers to provinces temporarily, the Quebec government also spent $21 billion on COVID-related relief and support measures in 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 (about 8.4 per cent of the province's total expenditures in the period) (Government of Quebec, 2022). Of this provincial spending, more than two-thirds ($14.7 billion) were allocated to the health and social services budgets.

Furthermore, the pandemic exposed health care sector vulnerabilities in a province characterized by labour shortages, a public health agency that suffered from a 30 per cent cutback in 2015, and among the lowest number of hospital beds per capita of all Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (Bertrand et al., Reference Bertrand, Jacques, Maioni, Birch, Dufresne, Duval and Tremblay-Antoine2022). In this context, the pandemic generated a consensus toward a significant reinvestment in health care expenditures: after a growth in recurrent spending of 8.1 per cent in 2021–2022, the health care budget is projected to increase from $44.8 billion before the pandemic to $59.2 billion in 2024–2025, an average annual growth of 6.4 per cent (Government of Quebec, 2022).

Driven by record high inflation, the total amount of recurrent program expenditures expressed in nominal dollars increased by 15 per cent in each of the 2021 and 2022 budgets (Government of Quebec, 2022). The significant increase of expenditures in the 2022–2023 budget postpones the return to balanced budgets to 2027–2028, whereas the government could have achieved surpluses four years earlier had it chosen to maintain spending growth to projected budget levels (Dinan and Tellier, Reference Dinan, Tellier, Birch, Dufresne, Duval and Tremblay-Antoine2022). Not only did the CAQ government follow a shift in public opinion that has become more tolerant of deficits over time (Jacques and Bélanger, Reference Jacques and Bélanger2022), it also consciously decided to move toward the centre to satisfy public demand for social spending.

Income Support

Quebec is known within Canada's liberal welfare regime for its exceptionalism in poverty reduction. Scholars argue that this is the result of generous income support policies emphasizing labour market participation and of social investment policies targeting families with young children (van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, Plante, Raiq, Proulx and Faustmann2017). Modern income support programs in the province were spearheaded by PQ governments in the mid to late 1990s, distinguishing Quebec from other Canadian provinces by establishing comparatively generous social assistance schemes and giving stakeholders an important role.

The main contours of Quebec's income support were not modified during the CAQ's first term in office. Income support in the province broadly distinguishes between persons deemed able and unable to work. Since 2005, Social Solidarity is provided to individuals and families with severe employment limitations and the less generous Social Assistance provided to individuals and families without these limitations. This portrayal of deservingness coincides with public opinion data showing that Quebeckers use the ability to work as a key criterion for social assistance generosity (Landry et al., Reference Landry, Blanchet, Rocheleau, Gagné, Caidor and Caneva2021).

Whereas work remains a key criterion for benefit types and levels, income support programs in the province have also long emphasized families. We argue that this is critical to understanding the CAQ's behaviour in office, because these policies have created strong electoral constituencies. An analysis of social spending in 2019 shows that nearly 42 per cent is destined to go to families with children (Provencher et al., 2020: 5). Moreover, although welfare incomes have increased across household types in the province, they remain highest for households with children, particularly couples with two children (Laidley and Tabbara, Reference Laidley and Tabbara2021: 119–20). In addition to the creation of childcare programs, explained in the next section of this article, Quebec enacted its own Parental Insurance Plan in 2006, which is more generous than the federal Employment Insurance (Noël, Reference Noël and Hemerijck2017: 268).

Despite these broad trends in income support, QLP governments between 2003–2012 and 2014–2018 reduced program generosity and reinforced employment status as a criterion for social assistance. This has taken the form of stricter criteria to access social assistance, rather than increased activation funding (Dinan and Noël, Reference Dinan and Noël2020). Observers further argue that the Couillard Liberal government adopted a series of reforms associated with punitive policies targeted against groups not considered to be “deserving poor” in the province (Larocque, Reference Larocque, Pétry and Birch2018), which stymied progressive reforms (Noël, Reference Noël, Goodyear-Grant, Johnston, Kymlicka and Myles2018). The Couillard government did not solely raise conditionality for income assistance; it also made policies more generous for groups it deemed deserving of income support, namely people with severe employment limitations, older adults, low-income families, and persons with severe disabilities (Larocque, Reference Larocque, Pétry and Birch2018).

Changes to social assistance were not at the forefront of the 2018 electoral campaign, with only the left-wing party Québec solidaire proposing increases to it. Indeed, as part of the opposition, the CAQ resoundingly voted in favour of 2016 reforms to social assistance that drastically reduced benefits for new claimants refusing to participate in employment reintegration activities (Quebec, National Assembly, 2016). Yet if increases to social spending were not a significant debate during the election, income assistance for families has been a clear priority for the CAQ both during the electoral campaign and throughout its mandate. This has included minor changes to social assistance for low-income families, the creation of a more generous child transfer, and the promise to increase financial support for children with disabilities. Through such changes, the CAQ maintains the distinction between the deserving and undeserving poor in ways that coincide with a key part of the electorate. These campaign promises were quickly adopted during the CAQ's first two years in government. This continuity with minor expansion characterizes the CAQ's social assistance policy prior to the exogenous shock of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Continuing its electoral strategy of emphasizing families, the CAQ created a flagship policy, the Family Allowance in 2019. In part a fulfillment of campaign promises to reinvest in families, the allowance is a nontaxable universal benefit for families with children under the age of 18. Not a novel concept in a province known for its generosity toward families (Godbout and St-Cerny, Reference Godbout and St-Cerny2008), this policy merges existing family transfers last modified by the QLP in 2005. The CAQ's emphasis on child transfers is typical of socially conservative parties aiming to boost family income without altering traditional gender roles (Hieda, Reference Hieda2013). This new policy repackages and increases existing family supports. For instance, while the financial support provided to families is graduated based on income, the amount given per child was increased and made constant. This is a change from the previous policy, which provided less support for families with multiple children. According to the Finance Ministry (2020, 2021) reports, these changes cost approximately $2,655 billion in 2019 and $3,231 billion in 2020. When compared with spending by the previous government in 2018, this is an $830.3 million increase (Quebec, Finance Ministry, 2019, 2021). This, in addition to the childcare policies discussed in the next section, has allowed the CAQ to distance itself from previous unpopular reforms under Liberal governments and claim credit for these electorally popular policies that are known to be a key part of the province's welfare heritage.

In addition to these new expenses, income support for families continued to be a priority for the Legault government, which took advantage of favourable economic circumstances before the pandemic to reinvest in family programs. This reinvestment included changes to the Quebec Parental Insurance Plan (QPIP), a popular program with take-up of nearly 90 per cent (Government of Quebec, 2020b). The new law, introduced in 2019 and adopted in 2020, extended the benefit period, allowed for more flexibility in the division of benefits between parents, and made it easier for mothers to adopt a gradual pace back to work. Further changes were made in response to criticisms about inequality within the QPIP, enabling single and adoptive parents to gain access to this form of income assistance, which was already the most generous and accessible in the country (Mathieu, Reference Mathieu2021b). These changes were largely possible due to record programmatic surpluses in 2019 and to popular support. Continuing these trends, additional support was given to families during the pandemic. This change can be partly attributed as a response to criticism from Québec solidaire during the pandemic. Finally, these new expenses coincide with a reduction in employee contributions to the program. This could create a deficit situation for the program by 2024 (Larin, Reference Larin2021) and lead to the possibility of increased contributions in the future.

We argue that changes to income support for families adopted during the CAQ's first two years in office align with the Quebec Model, which has long supported families with young children. Furthermore, the possibility of programmatic deficits demonstrates that the Legault government preferred to increase spending for families rather than reduce expenses. Finally, aligning with the median voter model, these changes show this government's willingness to change tracks when faced with opposition on family issues.

The CAQ government also announced new spending measures during its 2021 fall economic update in response to rising inflation, which at the time had reached its highest point since 1991. During its March 2022 budget, the government further announced a one-time refundable tax credit, with the amount being gradually reduced for individuals making up to $105,000 a year. This policy, which will cost approximately $3.2 billion (Government of Quebec, 2022), shows the CAQ's willingness to increase expenditures in electorally strategic ways. Although certainly designed to please the median voter in a context of an inflation crisis, this spending cannot be explained by existing policy legacies, as the policies are ad hoc measures not directly tied to existing policy legacies. Rather, it demonstrates how the CAQ government continues to adjust its policies to the prevailing electoral mood and economic context.

During four years in government, the CAQ government did not, as some may have expected given its right-wing identity, retrench income support. Rather, it maintained existing supports with minor adjustments. Moreover, fulfilling campaign promises, the CAQ significantly expanded income supports for families and corrected policy flaws. These changes highlight the important role this target group plays for the CAQ government and the feedback effects resulting from existing family policies.

Childcare

Canada remains among the OECD countries with the least developed public childcare services. In 2013, public expenditures in childcare reached an average of only 0.2 per cent of GDP in provinces outside Quebec, among the lowest of all OECD countries. In contrast, in 1997 the PQ invested in an ambitious family policy under the Bouchard government that led to the creation of public Centres de la Petite Enfance (CPE) that have an important educational component. By the end of the PQ government's tenure, childcare public expenditures were close to the OECD average, with public expenditures reaching 0.7 per cent of GDP in 2013 (Arsenault et al., Reference Arsenault, Jacques and Maioni2018).

The QLP defeated the PQ in 2003 but had little political incentive to dismantle Quebec's childcare network, given its massive popularity. The PQ's childcare reform strongly benefited the middle and upper middle classes, which helped draw broad popular support. Such a universal program benefiting a large segment of the population is more likely to be widely popular and resilient to retrenchment than targeted programs for the poor (Jordan, Reference Jordan2014). Following the election of Jean Charest's government in 2003, unions and community groups formed a “vigilance network” to oppose any “neoliberal threats,” including to childcare (Boismenu et al., Reference Boismenu, Dufour and Saint-Martin2004).

Unable to retrench the program but unwilling to expand public childcare, QLP governments decided to support the creation of private childcare centres to satisfy the demand for additional childcare, notably by increasing tax credits for private childcare (Mathieu, Reference Mathieu2019). This policy aimed to increase parents’ “freedom of choice” and to reduce the cost of childcare for the public treasury (Fortin, Reference Fortin2018). As a result, Quebec's “universal” childcare system is a patchwork of public CPEs, representing less than two-thirds of childcare places, and for-profit private childcare centres, some of which are partially financed through public funding (Mathieu, Reference Mathieu2019). It should also be noted that the network remains incomplete, with waiting lists for CPEs growing and reaching 51,000 children by 2019 (Quebec, Auditor General, 2020).

The development of CPEs was not a priority for the CAQ when the party was in opposition. Geneviève Guilbault, the party's family policy critic, fully supported the private daycare management model, and the party promoted the implementation of kindergartens for four-year-olds within the regular elementary school system (Pilon-Larose, Reference Pilon-Larose2017). Moreover, as discussed in the previous section, the CAQ prioritized family allowances rather than public childcare.

Despite the intent to create kindergartens for four-year-olds, past institutional arrangements significantly constrained the government's ability to do so. The government promised 5,000 kindergarten classes but revised this to 2,600 two years after the initial deadline it set. This change can be explained by how the growth of kindergartens was perceived as a zero-sum tradeoff with the development of childcare spaces in the existing system, which was supported by unions, academics and the educational sector. Additional structural obstacles include a shortage of qualified teachers and a lack of infrastructure in existing schools. The latter increased the cost per new kindergarten class from a projected $120,000 to $1.2 million (Lajoie, Reference Lajoie2022). Thus, institutional stickiness is one factor that forced the government to change course and to focus instead on the improvement of the childcare network.

During the 2018 election campaign, the CAQ promised to create 28,000 spaces in CPEs, improve their management and quality standards, make their schedules more flexible, and reduce waiting lists. To distinguish itself from the Couillard government that increased childcare fees for parents with higher incomes, the CAQ promised, and quickly implemented, a return to flat fees for public childcare (CAQ, 2018a).

During the first two years of the CAQ government, not much attention was put into childcare until the Auditor General published a devastating report in October 2020. The report highlighted the slow pace of the creation of new spaces promised by the government, the poor quality of private childcare services, opaque and long waiting lists, and inequities in access (Quebec, Auditor General, 2020). The report, along with the COVID-19 pandemic, contributed to putting childcare back on the government's agenda.

In its April 2021 federal budget, the Trudeau government proposed a massive federal investment in childcare, recognizing that the pandemic-induced recession was particularly detrimental to mothers’ labour market participation and convinced of the importance of an expansionary fiscal policy to create a sustainable economic recovery. This investment is crucial for other Canadian provinces, whose low levels of public investment result in particularly high childcare fees.

In Quebec, these federal investments, which were directly inspired by the Quebec Model, allowed the Legault government to propose a particularly ambitious reform of childcare services contained in Bill 1, as the federal transfers represented an additional transfer of $6 billion over five years. Tabled in the fall of 2021, and described by the Family Minister Mathieu Lacombe as “the most important reform since the creation of the network,” this bill provides for the allocation of at least $3 billion until 2024–2025 to create 37,000 additional spaces in the network, notably by simplifying the bureaucratic process for creating new spaces. It also implements a one-stop waiting list system and makes childcare centres’ schedules more flexible (Pilon-Larose, Reference Pilon-Larose2021). In addition to building upon existing policies, these investments deviate from the CAQ's 2018 strategy, which emphasized a new model: kindergartens for four-year-olds within the regular elementary school system.

The pandemic increased demand for social programming and for additional childcare places, prompting the Legault government to invest a substantial portion of the federal transfer in improving the childcare system. Moreover, the lack of spaces in the suburbs of Montreal (Quebec, Auditor General, 2020), which includes ridings crucial to the CAQ's re-election, motivated the Legault government to take advantage of federal investments to expand this network rather than allocating the transfer to other priorities such as tax reductions. Indeed, the Quebec government could have redirected all the transfer to its general budget, as its childcare program is more developed than that of any other Canadian province. Several interest groups— including unions and childcare associations but also business groups such as the Fédérations des chambres de commerce du Québec—have pushed the government to use the federal transfer to substantially invest in the childcare network (Milliard, Reference Milliard2021).

However, Bill 1 does not directly address the substandard quality of private education services. The government could have offered commercial daycare centres the possibility to become CPEs or forced them to maintain higher quality standards (Mathieu, Reference Mathieu2021a). Faced with an already highly developed private network, the government decided instead to increase the tax credit for nonsubsidized daycare centres. In fact, Mathieu Lacombe stated that his goal was to prioritize public childcare but that the government must consider the existing network of private providers (Pilon-Larose, Reference Pilon-Larose2021). In this case, path dependence works against the expansion of the public network.

In short, the Legault government's position on childcare policy suggests that the strength of policy feedback generated by existing policy legacies and the public demand for additional spending may have pushed the government to significantly expand childcare spaces. We consider this as a move toward the centre, away from the position advocated by the CAQ while in the opposition.

Long-term care

As in other Canadian provinces, Quebec does not offer generous and accessible long-term care (LTC) services. The policy area is highly fragmented, with limited government support centred strongly on medical needs and with informal caregivers and community groups providing most support. There is no mandatory contributory LTC scheme, as in France and South Korea, and no elaborate cash transfers to municipalities, as in Scandinavian countries. In terms of LTC spending as a percentage of GDP, Canada stands at 1.3 below the OECD average of 1.7 and is comparable to the United Kingdom (1.4) and Ireland (1.3) (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2019: 239). Hence, contrary to other policy areas, long-term care in Quebec—and in the other provinces—is clearly aligned with expectations of a liberal welfare regime, due to Canada's hospital-centric health care system (Marier, Reference Marier2021).

Across Canada, long-term care is embedded within health care departments (with the noticeable exception of New Brunswick), and it is considered an “extended service” in the Canada Health Act. This further contributes to the marginalization of long-term care, since it is not subjected to the federal framework regulating transfers between the federal government and the provinces. Consequently, the provinces have developed different governance models of long-term care, with the most distinctive feature being the vast difference in privatization. Private operators represent a small portion in provinces such as Quebec and Manitoba but the majority in Ontario (Marier, Reference Marier2021: 145–46). Still, with little variation across Canada, 82 per cent of the LTC budget is devoted to nursing homes, a figure that has been stable since the 1970s (Grignon and Spencer, Reference Grignon and Spencer2018).

In Quebec, the previous Liberal government (2014–2018) faced growing calls to improve LTC policies, in response to limited access to nursing homes (known as CHSLD), public reports on the declining quality of services within these institutions, and stagnant home care support despite its priority as a policy goal in long-term care. One illustration of the impact of austerity measures put in place by successive Liberal governments is that the number of beds per 1,000 in CHSLD for individuals aged 75 and above declined by 17 per cent between 2010–2011 and 2016–2017 (Quebec, Commissioner of Health and Welfare, 2017). The government sought to defend its record throughout its mandate; in one instance, the Minister of Health invited Members of Parliament to a dinner in a CHSLD, in order to vouch for the quality of the food—a media event that ended up drawing widespread criticism (Lacoursière, Reference Lacoursière2016).

In the wake of prolonged austerity measures, the CAQ developed an electoral platform promising additional funding in home care, the renovation of existing CHSLDs, and the creation of the Maisons des aînés offering better living quarters than the old CHSLD. Illustrative of policy feedbacks in long-term care, the creation of the Maisons des aînés was the CAQ leader's first electoral promise on the campaign trail and was presented as a generational project (CAQ, 2018b), even though policy orientations and popular opinions strongly favour a shift toward home care (Marier, Reference Marier2021: 163–64). Following the 2018 election victory, the government announced $2.6 billion in new spending to develop 2,600 LTC spaces within the Maisons des aînés and the modernization of 2,500 existing places in CHSLD (Quebec, MSSS, 2019). Most criticism of the new plan centred on the projected costs of the Maisons des aînés, as well as on the plan's limited impact on current waiting lists for home care services and on access to a space in CHSLDs.

Interestingly, once in power, the CAQ government introduced a trio of health ministers, with the most noticeable surprise being the Minister Responsible for Seniors and Caregivers (Marguerite Blais). Blais occupied a similar position in the early 2010s while with the Liberal Party, but the seniors portfolio was part of the Ministry for Families, essentially to convey the message that aging is not a pathology. During her ministerial mandate with the Liberals (2007–2012), she led the growth of the Ministry for Families and put in place multiple social initiatives targeting seniors. Her nomination within the Ministry of Health and Social Services in 2018, along with the transfer of the Secretariat, illustrates the power and reach of policy feedbacks in the field of long-term care. As in the case of most other Canadian provinces regardless of political orientation, Quebec brought back the senior portfolio within the health ministry with a hospital-centric view, making it increasingly improbable to move beyond an institutionalized model of long-term care, since the dominant problem definition centres on the number of alternative level of care (ALC) beds occupied by seniors in hospitals (Marier, Reference Marier2021).

While a government should have expected some positive responses when adding resources in long-term care, the COVID-19 pandemic accentuated current shortcomings. As in other industrialized countries, older adults have represented the bulk of COVID-19 related deaths. As of March 23, 2022, 43.7 per cent of COVID-19 fatalities have occurred in CHSLD (and LTC units within hospitals) (Quebec, INSPQ, 2022). While COVID-19 has been particularly prone to trigger high levels of casualties in LTC residences (Gardner et al., Reference Gardner, States and Bagley2020), the governmental decision to focus primarily on hospitals without adequate planning for CHLSD led to a firestorm of criticism. The government faced highly critical assessments and inquiries from public authorities, such as the Office of the Coroner and the Ombud office (Duchaine, Reference Duchaine2022; Quebec, Ombudsman, 2021), for its (in)actions, whose conclusions have prompted opposition parties to request an independent and in-depth inquiry into the governmental response to COVID-19. The CAQ government has clearly sought to escape blame further by actively opposing this request. During the vote in the National Assembly in April 2022, the defeat of this motion even featured a standing ovation from governmental Members of Parliament. A few days later, the government announced that the Minister Responsible for Seniors and Caregivers, as well as the Minister of Health during the first wave of the pandemic, would not seek re-election.

The CAQ government has also opted to accentuate the deployment of resources to construct the Maisons des aînés, modernize CHSLDs, and increase funding in home care services. Most notably, it has been taking steps to ensure that all private CHSLD operate within a signed agreement with the Ministry of Health and Social Services. As of March 2022, over 40 establishments continue to operate autonomously (Duchaine and Lacoursière, Reference Duchaine and Lacoursière2022). These establishments have been singled out on multiple occasions for the lack of care offered to residents prior to and during the pandemic.

So far, the CAQ's response in long-term care suggests measures consistent with policy feedbacks and institutional lock-in effects, as it perpetuates the stronghold of CHSLDs within this policy area. Documents from the leading organization representing seniors, FADOQ, also illustrate that the CAQ has focused on adjusting existing programs, with the notable exception of the Maisons des aînés. For instance, the January 2020 policy document submitted as part of budgetary consultations did not criticize a specific reform but rather focused on 36 long-standing FADOQ demands, such as the creation of a national aging policy, increasing budgets for home care, and enhancing various tax credits beneficial to seniors (FADOQ, 2020). The emphasis on modernizing CHSLD and building Maisons des aînés perpetuates the hospital-centric orientation of long-term care in the province; the dominant problem definition remains the lack of acute care beds and the use of ALC places by older adults in hospitals. As such, there is no indication that a major shift in long-term care is ongoing, even though home care spending benefited from added spending. Despite the overwhelming amount of criticism the government faced in the aftermath of COVID-19, recent surveys suggest that the CAQ remains dominant within Quebec's increasingly fragmented party system (Fournier, Reference Fournier2022). Part of the reason could be that the government has deflected blame on numerous occasions by emphasizing the impact the previous Liberal government had on health care and suggesting that those policies are the main source of current difficulties experienced in long-term care.

Discussion and Conclusion

How do political parties located on the right of the political spectrum adapt to electoral constraints both outside of and during global crises directly affecting the welfare state? Drawing on the literature on policy feedback and the case of the CAQ government in Quebec (2018–), we offer a tentative answer, highlighting the role of policy feedback.

First, our analysis suggests that in key social policy areas such as childcare, existing policy legacies stemming from self-reinforcing effects have shaped the political strategies and the policy offerings of the CAQ government, which has crafted policies that remain largely consistent with the Quebec Model of economic and social development. These policies reject the unpopular austerity measures adopted by the previous government while promoting changes to the welfare state that most Quebeckers deem acceptable. This centrist approach is grounded in a desire to avoid a political backlash from a majority of voters who support generous family benefits and subsidized childcare, a situation compatible with self-reinforcing policy feedback. We argue that the CAQ sought support from voters attached to existing policies by expanding existing family policies and revamping programs such as the Family Allowance. Once access to subsidized childcare was back on the policy agenda in 2020, the government changed its strategy to work within the system. It also took advantage of the federal government's willingness to fund childcare by announcing an expansion of the existing network of childcare spaces. To this analysis, we can add institutional inertia stemming from the potential costs of moving away from existing policies and the importance of interest groups such as strong labour unions that are closely associated with the Quebec Model and its embedded policy legacies. In other words, three types of self-reinforcing policy feedback help to explain the CAQ's centrist social policy orientation: feedback from vested interests, which focuses on interest groups; feedback from institutional inertia, which stresses the potential costs of path-departing change; and feedback about mass politics (Pierson, Reference Pierson2000).Footnote 1

Second, the pandemic does not explain the CAQ's centrist turn in terms of social policy. In other words, this “exogenous shock” (Pierson, Reference Pierson2000) is not behind the centrist reorientation of the CAQ in the field of social policy, which predates the pandemic. The pandemic's effect on the CAQ's social policy decisions can be found in health care and, even more dramatically, long-term care, in which the pandemic forced the CAQ government to respond to underfunding and staff shortages affecting popular social programs (Bertrand et al., Reference Bertrand, Jacques, Maioni, Birch, Dufresne, Duval and Tremblay-Antoine2022). Thus, although the pandemic does not explain the centrist approach to social policy, it did influence key political decisions in long-term care closely linked to existing policy legacies.

Three main limitations prevent us from pursuing a deeper process tracing of the cases under investigation to prove that policy feedbacks are causing the CAQ's centrist social policy agenda. First, we could not rely on interviews with decision makers, since, as of the writing of this article, most of the key actors are still in government. It is therefore unlikely that they would offer a neutral assessment of the situation. This lack of hindsight also prevents us from relying on biographies of these key actors. Second, it is difficult to find several situations where interest groups participated to lock in policy legacies, since interest groups have been quieter and less visible during the pandemic, which lasted for more than half of the CAQ's first tenure in government. Third, our argument on public opinion is constrained by the absence of comparative surveys of social policy preferences focused on Quebec and the other provinces. Thus, more remains to be done to demonstrate whether the Quebec Model feeds back into public opinion and leads to higher public support for social policies among citizens of the province.

Overall, this article suggests that policy legacies—in our case, self-reinforcing feedback effects about interest groups and public opinion—do shape the political strategies of right-wing political parties when they face popular and well-entrenched social programs. Yet the issue here is not only about preventing the dismantling of the welfare state or even simply retrenchment and austerity policies (Pierson, Reference Pierson1994). On the contrary, decisions by right-wing parties to pursue selective social policy expansion in some policy areas are also related to existing policy legacies, in the case of self-reinforcing feedback effects (Béland et al., Reference Béland, Prince and Kent Weaver2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Eric Montigny, Alain Noël and the anonymous reviewers for their useful comments and suggestions.