Common mental disorders (CMDs) such as depression, anxiety disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are more prevalent among individuals who have a history of childhood maltreatment.Reference Chapman, Whitfield, Felitti, Dube, Edwards and Anda1,Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart and Mikton2 This includes physical, sexual and emotional abuse, as well as neglect. There is also a dose–response relationship, meaning that the more severe and frequent the child maltreatment, the greater the risk of developing mental health issues.Reference Chapman, Whitfield, Felitti, Dube, Edwards and Anda1,Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart and Mikton2 However, most evidence comes from cross-sectional studies, in which people with a history of neglect or of sexual, physical and/or emotional abuse were more likely to experience mental health problems.Reference Chapman, Whitfield, Felitti, Dube, Edwards and Anda1,Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart and Mikton2 Such retrospective data are reliant on memories of past events that may alter over time depending on resilience, recovery or the severity of child maltreatment, and these studies cannot eliminate the possibility that child maltreatment might be both a cause and an effect.Reference Widom, Raphael and DuMont3

Longitudinal studies offer more robust evidence, and several have extended for up to 40 years of follow-up. However, these studies are often limited in scope. Examples include studies of particular types of child maltreatment,Reference Gilbert, Widom, Browne, Fergusson, Webb and Janson4,Reference Spataro, Mullen, Burgess, Wells and Moss5 as well as studies in certain populations such as females,Reference Trickett, Noll and Putnam6 individuals receiving treatment or those identified as being at high risk.Reference Norman, Byambaa, De, Butchart, Scott and Vos7 Where prospective data are available, a limitation of previous research is that only overall child maltreatment has been considered, without comparisons between different subtypes.Reference Sidebotham and Heron8–Reference Scott, Smith and Ellis10 Our previous work with a prospective birth cohort who were followed up to the age of 30 years old attempted to address some of these issues.Reference Kisely, Strathearn, Najman, Martin, Preedy and Patel11,Reference Strathearn, Giannotti, Mills, Kisely, Najman and Abajobir12 This was the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy (MUSP) cohort. There were 7223 participants, of whom 7214 had records that were potentially linkable to notifications of child maltreatment reported to Queensland-wide statutory agencies up until 16 years of age. We identified that agency-reported and/or substantiated cases of neglect or emotional, sexual and physical abuse were associated with affective symptoms in both adolescents and young adults, including internalising behaviours, depression and anxiety at both 21 and 30 years old.Reference Kisely, Abajobir, Mills, Strathearn, Clavarino and Najman13,Reference Kisely, Strathearn and Najman14 The association was particularly strong for PTSD.Reference Kisely, Abajobir, Mills, Strathearn, Clavarino and Najman13,Reference Kisely, Strathearn and Najman14 However, to date, there has been no information from later years on this cohort and a significant drawback has been the impact of attrition. Of the initial group of 7214 participants, only 33.6% (2427 individuals) remained in the study after 30 years. Those who were not followed up were more likely to come from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, which may have introduced bias.

The Childhood Adversity and Lifetime Morbidity (CALM) study was intended to alleviate the impact of attrition by linking administrative health data to the MUSP birth cohort.Reference Kisely, Leske, Arnautovska, Siskind, Warren and Northwood15,Reference Kisely, Arnautovska, Siskind, Warren and Najman16 The aim of the present study was therefore to examine the associations of child maltreatment with emergency department presentations and in-patient admissions for CMDs in individuals up to 40 years old.

Method

Ethics statement

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects were approved by both The University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) (2021/HE001925) and the Metro South Health HREC (HREC/2022/QMS/83690). A waiver of consent was received by both HRECs relative to the inability to obtain consent from all participants whose data were used in this study. As in other work, we prospectively registered a pre-trial protocol with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12622000870752).Reference Kisely, Leske, Arnautovska, Siskind, Warren and Northwood15,Reference Kisely, Arnautovska, Siskind, Warren and Najman16 We followed the STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology) guidelineReference von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke17 and the RECORD (REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data) statement.Reference Benchimol, Smeeth, Guttmann, Harron, Moher and Petersen18

S.K. affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and registered) have been explained.

Participants

The MUSP study recruited participants who were born at the Mater Mothers’ Hospital, Brisbane's principal obstetrics unit, between 1981 and 1983.Reference Kisely, Leske, Arnautovska, Siskind, Warren and Northwood15,Reference Kisely, Arnautovska, Siskind, Warren and Najman16 In September 2000, agency-reported notifications of child maltreatment made to the Department of Families, Youth and Community Care were accessed and linked to the longitudinal database (n = 7214).Reference Strathearn, Giannotti, Mills, Kisely, Najman and Abajobir12 Child maltreatment reports were substantiated if, after investigation, there was reasonable belief that child maltreatment had occurred. There were four subtypes of child maltreatment, comprising neglect and physical, sexual and emotional abuse.

Health data sources

As previously outlined,Reference Kisely, Leske, Arnautovska, Siskind, Warren and Northwood15 we used encrypted identifiers to anonymously link the MUSP cohort to the two relevant Queensland Health administrative databases. One was the Queensland Hospital Admitted Patients Data Collection (QHAPDC), comprising psychiatric admissions to both public (from 1 January 2000) and private (from 1 July 2007) facilities throughout Queensland. The other was the Emergency Data Collection (EDC), comprising all emergency department presentations state-wide (from 2008). As a result, participants were at least 16 years old on admission or presentation. We used the most recent episode to identify cases of CMDs in each database. A case of CMD was defined as any admission or emergency department presentation with a primary diagnosis of depression, anxiety, PTSD or other non-psychotic disorders (ICD-10-AM codes F32–F45.9). This is consistent with the definition of CMD used by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the UK.19 Bipolar affective disorder was excluded (ICD-10-AM codes F30–F31.9), as this is generally considered to be a persistent or severe mental illness, although there is no standard definition of either term.Reference Gonzales, Kois, Chen, López-Aybar, McCullough and McLaughlin20

Data linkage and quality

The published protocol provides full details of the data linkage, which was performed by the Statistical Services Branch (SSB) of Queensland Health.Reference Kisely, Leske, Arnautovska, Siskind, Warren and Northwood15 The MUSP data custodian provided a data-set containing only the names, birth dates and sex of the birth cohort participants to the SSB. Within the SSB, these details were matched using the Queensland Health Master Linkage File (MLF). The SSB subsequently assigned a unique key to each linked record and shared this with the three data custodians, who used it as an identifier for the de-identified records that were sent to the researchers (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Illustration of emergency department presentations, in-patient admissions and Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy (MUSP) birth cohort database linkages.

The accuracy of linkages was optimised through a comprehensive review of all potential matches, with each linkage process undergoing cross-verification by the Project Linkage team manager. The MLF utilised various custom ChoiceMaker ‘models’ to establish the linkage map, using weighted tests to compute a match probability for pairs of records and incorporating machine learning. Identifying information pairs were manually examined to validate their accuracy. Error rates were consistently low, with 99.5% for false positives and 98% for false negatives. Further details about data quality are available in the Queensland Data Linkage Framework.21

Subsequent steps included cleaning and standardisation of identifying variables, accompanied by quality assurance checks for missing or duplicate data. When cross-referenced with other sources, sociodemographic characteristics such as Indigenous status were accurately identified in 89% of cases.Reference Kisely and Pais22

Statistical analysis

We measured bivariate associations between the overall category of child maltreatment (agency-reported versus substantiated) and emergency department presentations or psychiatric admissions for CMDs. Hospital admissions and emergency department presentations were strongly skewed to the right. As a result, both were dichotomised into ‘never occurred’ versus ‘ever occurred’. We initially examined the association of CMD health service use with agency-reported and substantiated child maltreatment.

Logistic regression models, adjusted for covariates that had been identified in prior research as possibly confounding the relationship between child maltreatment and adverse psychological outcomes at follow-up, were also used. Covariates included baseline participant gender, parental racial origin, parental relationship status and low family income. Adjustment for marital status at the time of the most recent record in either QHAPDC or EDC was also undertaken. This was the sole sociodemographic variable consistently documented in the administrative data, apart from age and gender. We used the most recent record regardless of diagnosis (psychiatric or non-psychiatric), giving preference to QHAPDC data as these were the most complete. Single status was defined as having never been married or in a de facto relationship.

Where there were sufficient numbers, we conducted subgroup analyses examining the associations of child maltreatment with emergency department presentations and admissions for depression and anxiety/stress related disorders separately. As in previous work, we also conducted two sensitivity analyses.Reference Kisely, Arnautovska, Siskind, Warren and Najman16 The first was a propensity score analysis to examine the impact of adding a variable representing potential baseline confounders across the entire MUSP cohort. This was done in case specific sociodemographic characteristics were associated with difficulties in successfully linking the MUSP participants to Queensland health data. We opted for this approach over multiple imputation because it was not possible to assume that the data were missing at random. The second was to measure the effects of including marital status following imputation in the regression models. We only did this as a sensitivity analysis given that, as before, we could not assume that the missing data followed a random pattern.

Results

Of the 7214 participants, 121 died over the study period. Of those who remained, 1006 (14.4%) had insufficient details (e.g. no first name) to link to the Queensland Health databases (Fig. 2). As previously reported, individuals with missing details were significantly more likely to be from an Indigenous background (odds ratio 2.26; 95% CI = 1.80–2.83), to have had parents who were living apart (odds ratio 1.57; 95% CI = 1.32–1.87) or to have been on a low income at baseline (odds ratio 1.67; 95% CI = 1.46–1.92).Reference Kisely, Arnautovska, Siskind, Warren and Najman16 These findings suggest that data were not missing at random. Of the 6087 participants whose records could be linked, just over half were male (n = 3143), and 5% (n = 326) were Indigenous Australians. Details on relationships at the time of the most recent emergency department presentation or hospital admission were available for 4610 of the 6087 individuals (76%), of whom 1660 (27.3%) were single.

Fig. 2 Illustration of how the final study sample size was derived. MUSP, Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy.

Child maltreatment

There were 609 participants (10.1%) who had been the subject of at least one agency-reported notification to child protection services. In 309 cases, this had involved two or more child maltreatment subtypes. Reports were most commonly for neglect (n = 364), followed by physical abuse (n = 359), emotional abuse (n = 333) and sexual abuse (n = 197).

There were 389 participants (6.4%) whose child maltreatment was substantiated, physical abuse being the most frequent (n = 204). This was followed by emotional abuse (n = 199), neglect (n = 192) and sexual abuse (n = 109). Notifications were more common in participants who were female (52.2% v. 47.9%; odds ratio 1.20; 95% CI = 1.02–1.42) or Indigenous (10.2% v. 4.8%; odds ratio 2.27; 95% CI = 1.69–3.03), as well as in those whose parents were not living together (26.4% v. 11.3%; odds ratio 2.83; 95% CI = 2.32–3.45) or had a low family income at baseline (46.0% v. 28.5%; odds ratio 2.14; 95% CI = 1.80–2.53). Of the 4160 individuals with details on relationships at the time of the most recent emergency department presentation or hospital admission, child maltreatment notifications were more common in those of single status (41.1% v. 35.4%; odds ratio 1.27; 95% CI = 1.05–1.54).

Emergency department presentations

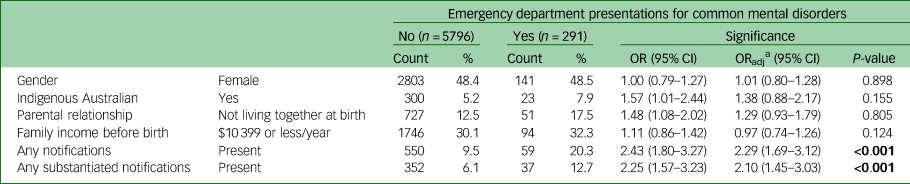

There were 291 participants who presented to an emergency department at least once for CMDs. Of these, 75 (25.8%) presented with depression at their last contact and 216 (74%) with anxiety. In unadjusted and adjusted analysis, both agency-reported and substantiated notifications for child maltreatment were associated with emergency department presentations for CMDs (Table 1). As shown in Table 2, after adjustment for baseline variables, all subtypes of agency-reported and substantiated child maltreatment were significantly associated with emergency department presentations for CMDs. Significant associations were also evident where two or more agency-reported notifications were reported.

Table 1 Variables associated with emergency department presentations for common mental disorders

OR, odds ratio; ORadj, adjusted odds ratio.

Bold is to highlight statistical significance where present.

a. Variables used in adjustment included baseline gender, parental race, parental relationship, family income. Covariates were not included in the adjusted model they were the predictor variable of interest.

Table 2 Association between child maltreatment and emergency department presentations for common mental disorders by 40 years old

OR, odds ratio; ORadj, adjusted odds ratio.

Bold is to highlight statistical significance where present.

a. Variables used in adjustment: gender, parental race, parental relationship and family income at baseline.

b. Variable used in adjustment: single marital status at most recent admission.

Admissions

One hundred and eighty-nine individuals (3.1%) had been admitted at least once for a CMD, either for depression (n = 86) or for anxiety, stress and/or adjustment disorders (n = 103). In both unadjusted and adjusted analysis, agency-reported notifications and substantiated notifications of child maltreatment were significantly associated with in-patient treatment for CMD (Table 3). As shown in Table 4, after adjustment, there were significant associations between admissions for CMDs and agency-reported physical, emotional and sexual abuse. There were also significant associations between admissions and substantiated notifications of neglect and physical abuse on adjusted analyses. Significant associations were also evident where two or more agency-reported notifications were reported.

Table 3 Variables associated with admissions for common mental disorders

OR, odds ratio; ORadj, adjusted odds ratio.

Bold is to highlight statistical significance where present.

a. Covariates were not included in the adjusted model if they were the predictor variable of interest. Variables used in adjustment: baseline gender, parental race, parental relationship and family income.

Table 4 Association between child maltreatment and admissions for common mental disorders by 40 years old

OR, odds ratio; ORadj, adjusted odds ratio.

Bold is to highlight statistical significance where present.

a. Variables used in adjustment: gender, parental race, parental relationship and family income at baseline.

b. Variable used in adjustment: single marital status at most recent admission.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

Sufficient numbers to undertake subgroup analyses were available only for the associations of anxiety/stress and depression with child maltreatment notifications overall. In the case of anxiety, there were significant associations for emergency department presentations (adjusted odds ratio (ORadj) = 2.23; 95% CI = 1.62–3.26; P ≤ 0.001) and admissions (ORadj = 2.73; 95% CI = 1.68–4.43; P ≤ 0.001). However, for depression, the association with child maltreatment notification was significant only for emergency department presentations (ORadj = 2.10; 95% CI = 1.15–3.84; P = 0.016), not for admissions (ORadj = 1.34; 95% CI = 0.70–2.58; P = 0.374).

Single status showed significant associations of agency-reported and substantiated child maltreatment notifications with admissions for CMDs (odds ratio 1.34; 95% CI = 1.002–1.80) and emergency department presentations for CMDs (odds ratio 1.46; 95% CI = 1.15–1.85). Including this variable did not alter the significance of associations for any of the child maltreatment subtypes (Tables 2 and 4). Similar results were found when propensity score weighting was applied (Tables 2 and 4).

Discussion

Most previous studies on the association between child maltreatment and CMDs in adulthood have relied on participants reporting past child maltreatment experiences. By contrast, this study gathered information on child maltreatment as it was reported to statutory authorities, with these reports being linked to subsequent administrative health data. Use of state-wide databases minimised attrition and enabled the examination of associations of different child maltreatment subtypes with emergency department presentations and hospital admissions for CMDs. By using administrative health records, it was possible to reduce the effects of attrition and reporting bias that may have limited the generalisability of findings from previous studies involving the MUSP cohort.Reference Kisely, Strathearn, Najman, Martin, Preedy and Patel11,Reference Strathearn, Giannotti, Mills, Kisely, Najman and Abajobir12

In earlier studies of the MUSP cohort, the presence of CMDs including depression, anxiety and PTSD was measured at 21- and 30-year follow-ups using standardised instruments such as the Centre for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI).Reference Kisely, Strathearn, Najman, Martin, Preedy and Patel11,Reference Strathearn, Giannotti, Mills, Kisely, Najman and Abajobir12 Both studies reported significant associations between PTSD and agency-reported and/or substantiated child maltreatment. The strength of findings for depression and other forms of anxiety varied by standardised instrument and time of follow-up. For instance, depressive symptoms on the CES-D at 21-year follow-up were strongly associated with substantiated abuse, but there was no such association for the CIDI results. This was possibly because the CES-D is a screening rather than a diagnostic tool.Reference Vilagut, Forero, Barbaglia and Alonso23 In addition, the CES-D results had greater statistical power, as the instrument was completed by 3778 participants, as opposed to the 2508 who completed the CIDI interview.Reference Kisely, Abajobir, Mills, Strathearn, Clavarino and Najman13 By contrast, results for anxiety using the CIDI were significant even given the smaller number of participants completing the interview.Reference Kisely, Abajobir, Mills, Strathearn, Clavarino and Najman13 At 30-year follow-up, however, the results for CIDI-defined depression were significant, but those for anxiety were not. In terms of child maltreatment subtypes, the most consistent associations were for emotional or sexual abuse and neglect.Reference Kisely, Strathearn, Najman, Martin, Preedy and Patel11 Significant findings for sexual abuse were limited to PTSD at 21-year follow-up.Reference Strathearn, Giannotti, Mills, Kisely, Najman and Abajobir12 However, comparatively few agency-notified participants were followed up at each time interval, which could have meant that these studies had insufficient numbers to achieve statistically significant results for all relevant outcomes such as sexual abuse.

An advantage of the CALM project is the greater sample size from both the birth cohort and administrative health data.Reference Kisely, Leske, Arnautovska, Siskind, Warren and Northwood15,Reference Kisely, Arnautovska, Siskind, Warren and Najman16 This allowed us to examine and confirm that almost all child maltreatment types had significant associations with CMDs of sufficient severity to result in an emergency department presentation or hospital admission. In addition, longer follow-up allowed a more accurate assessment of any associations with CMD, given that the peak age of onset of many CMDs is between 25 and 30 years of age.Reference Kessler, Amminger, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Lee and Ustün24 We only considered admissions from 2000 onwards to minimise the possibility that they occurred before any child maltreatment notification.

Explanations for our findings involve complex interactions between neurobiology, experience-dependent development and the wider social context, although there is still much to understand in the area. For instance, maltreatment during childhood can have direct neurobiological effects leading to long-lasting changes in brain neural structure and function, such as reduced grey matter volume in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, both of which have an important role in emotional regulation and memory processing.Reference Paquola, Bennett and Lagopoulos25 For instance, chronic stress experienced during childhood can dysregulate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, which plays a part in stress response, and may increase susceptibility to depression and other CMDs.Reference Shea, Walsh, MacMillan and Steiner26 In terms of psychological factors, child maltreatment can result in negative self-perceptions, low self-esteem, feelings of helplessness or hopelessness, and distorted beliefs about oneself and the world.Reference Mann, Hosman, Schaalma and de Vries27 Moreover, individuals who experience child maltreatment may also develop maladaptive coping mechanisms, such as substance misuse or self-harm, to deal with their emotional pain.Reference Kisely, Strathearn and Najman28,Reference Kisely, Strathearn and Najman29 These coping strategies can further exacerbate mental health problems.

In terms of social factors, child maltreatment is often accompanied by other disruptions in the social environment, such as unstable family relationships, social isolation or a lack of social support, which in turn can contribute to the development of mental health issues.Reference Frederick and Goddard30 Subsequently, child maltreatment may impair an individual's ability to form secure attachments and maintain healthy relationships. For instance, adults who have experienced child maltreatment may struggle with trust issues, social isolation, and difficulties in establishing and maintaining supportive social connections. In addition, individuals who have experienced child maltreatment may be at increased risk of re-victimisation in adulthood. This can include experiencing further abusive relationships or engaging in high-risk behaviours that increase the likelihood of adverse life events.

Limitations

As outlined in the protocol and previous work, there are limitations to this study.Reference Kisely, Leske, Arnautovska, Siskind, Warren and Northwood15,Reference Kisely, Arnautovska, Siskind, Warren and Najman16 First, the use of agency-reported notifications is likely to have led to significant underestimation of the true prevalence of child maltreatment, particularly as it reflects child protection policy in the 1980s and 1990s.Reference Gilbert, Widom, Browne, Fergusson, Webb and Janson4 Furthermore, there were even fewer substantiated reports. Second, CMDs were derived from administrative data that may be affected by potential recording bias. In addition, they do not encompass individuals with undiagnosed or untreated disorders, or those who received out-patient treatment. Moreover, about 14% of the MUSP cohort lacked sufficient information for linkage to administrative health data. On the other hand, associations were unaltered by adjustment for propensity scores that represented possible baseline confounders across the whole MUSP cohort. Missing information in the administrative data prevented adjustment for sociodemographic variables on admission other than marital status. Finally, there were insufficient numbers to analyse PTSD cases separately from other anxiety disorders.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our findings suggest that reducing child maltreatment might lower the risk of CMDs in later life. In terms of primary prevention, strategies could include home visiting by nurses, particularly for those families at greatest risk, as well as preschool enrichment, family engagement and parenting skill support.Reference Macmillan, Wathen, Barlow, Fergusson, Leventhal and Taussig31 Secondary prevention might include screening for maltreatment in people presenting with symptoms of CMD (particularly PTSD), as well as greater awareness that people who have experienced child maltreatment may be at higher risk of developing CMDs. Tertiary prevention could include enabling individuals who have experienced child maltreatment to gain easier access to clinical interventions such as cognitive–behavioural therapy and trauma-informed care.Reference Macmillan, Wathen, Barlow, Fergusson, Leventhal and Taussig31,Reference Cohen and Mannarino32 This does not necessarily mean direct treatment of childhood trauma from childhood. Rather, it suggests that clinicians should recognise that individuals seeking assistance may have encountered trauma during their youth, and that their current symptoms could be linked to that earlier trauma.Reference Knight33 Although trauma-informed care is increasingly available in specialist settings, it is also relevant to primary care, where most mental-health-related contacts occur.

At a systems level, there should be closer links between child protection and health services to improve the integration of prevention and early intervention initiatives through closer service partnerships between child protection and health systems.Reference Haslam, Mathews, Pacella, Scott, Finkelhor and Higgins34 A particular issue in Australia is fragmentation of care between levels of government. Initiatives to improve collaboration include the National Framework for Protecting Australia's Children and the National Strategy to Prevent and Respond to Child Sexual Abuse, as well as the National Office for Child Safety.Reference Haslam, Mathews, Pacella, Scott, Finkelhor and Higgins34

In conclusion, these findings underscore that child maltreatment may contribute to the development of CMDs. Yet again, these findings emphasise the significant public health implications of child maltreatment. Reducing child maltreatment could therefore play an important part in the primary, secondary and tertiary prevention of CMDs. The possibility of previous child maltreatment should be considered in individuals presenting to hospital with CMDs, whether as an emergency department presentation or admission.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the relevant data custodians and the Office of Research and Innovation of Queensland Health. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for this study. Contact details for Queensland Health custodians can be found at https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0034/843199/data_custodian_list.pdf. Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy data are available from a third party on reasonable request. Contact details can be found at https://social-science.uq.edu.au/mater-university-queensland-study-pregnancy?p=5#5. Analytic code is available from the corresponding author (S.K.) on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We thank the ALIVE National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation for their support in the conduct of this research.

Author contributions

S.K. formulated the research questions, designed the study, undertook data analysis and interpretation, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. C.B. and M.T. supported the interpretation of the results and critically reviewed the manuscript. U.A., D.S., N.W. and J.M.N. supported the design of the study and critically reviewed the manuscript. S.K., U.A., D.S., N.W. and J.M.N. obtained funding that supported this research. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the research.

Funding

This research was supported by Metro South Health Research Support Scheme (grant number RSS_2022_002). C.B. was funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Special Initiative in Mental Health Grant (GNT2002047) and D.S., in part, by an NHMRC Emerging Leadership Fellowship (GNT1194635).

Declaration of interest

S.K. and D.S. are both on the editorial board of the British Journal of Psychiatry. S.K. is also on the editorial board of BJPsych Open and BJPsych International.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.