GETTING THE JOKE

I remember this joke. Someone at school told it to me in my schooldays in Westphalia, West Germany. The memory is both distinct and vague. I suppose it happened in the early 1980s, when I was around ten years old. I had all but forgotten about the joke until a few years ago. It popped into my mind again like a ghostly apparition after I had begun to study the cultural meaning of the Volkswagen during the 1950s in West Germany.Footnote 1

“To study social life, one must confront the ghostly aspects of it” writes the sociologist Avery Gordon. “This confrontation requires (or produces) a fundamental change in the way we know and make knowledge.”Footnote 2 Gordon contends that an uncanny feeling stirred by a surprising encounter in the archive should be taken seriously as important information and therefore should be followed up. Ghostly matters, the title of Gordon's book, are ghostly because they arise insisting that they encapsulate something difficult, painful, and essential to what we study, yet they cannot be captured adequately with any of the conceptual frameworks that we have at our disposal. Confronting the ghostly means starting “with the marginal, with what we normally exclude or banish, or … never even notice.”Footnote 3How many Jews fit in a Volkswagen?

There is a historiographical tradition which has taken its clues, just as Gordon does, from anthropological insights about the importance of the marginal and of the odd detail as a starting point for studying hidden cultural structures and codes.Footnote 4 Robert Darnton illuminated eighteenth-century print culture in Paris by attempting to “get the joke” of “the great cat massacre.”Footnote 5 In such studies, the importance of starting with the odd detail derives in part from the fact that the cultural reality studied is quite far away from the historian's own reality and therefore requires such a method to make sense of it.Footnote 6 But where does it lead us if we try to “get” the Volkswagen joke in a similar way? Where does it lead us if we take the joke seriously as that marginal element possibly holding the key to “know” differently, and maybe better, an aspect of contemporary history that is all too well known. A contemporary historian who decides to start exploring a culture “where it seems to be most opaque”Footnote 7 enters a particularly strange terrain. The most opaque may turn out to be the most familiar, the most familiar may turn out to be the most obscure.

We usually assume that bizarre phenomena are either rare in contemporary European history or merely exist on the “margins” of society.Footnote 8 In that respect “our” extended present often begins shortly after 1945, closely linked to the establishment of “the West” as the dominant political and geographical framework of thinking. It is no coincidence that scholars of postcolonial history have been attuned to the dimensions of estrangement in contemporary history, to the difficulty of recognizing the familiar when it bears the traces of that which society does not want to know about itself. Ann L. Stoler has coined the term “colonial aphasia” to grasp how widespread insights about colonial and postcolonial history become systematically forgotten again, dissociated from the national histories and excluded from the prevalent narratives.Footnote 9 The Volkswagen's symbolic meaning in contemporary Germany is, as I want to argue, an example of a similar phenomenon.

The Volkswagen started out in 1938 as one of the Third Reich's most heavily propagated people's products. Hitler promised a “people's car” to every family within the racially defined Volksgemeinschaft and the German population received this promise with overwhelming enthusiasm. For years, the car was omnipresent in propaganda publications, various exhibitions, and press coverage. Yet, it was never produced in large numbers in the newly built factory east of Hannover. From 1939 onward, the Volkswagen factory, relying on forced labor, produced weapons instead, as well as around fifty thousand Kübelwagen, a military version of the Volkswagen delivered to the German Wehrmacht. When the production started again in 1946 and increased after 1948, it was the first time that the car as it was originally conceived became a mass-produced reality, populating German streets. Through its enormous success, both in Germany and abroad, the Volkswagen developed into a symbol of the “economic miracle,” of West Germany's new beginning. Eventually it became “one of West Germany's few largely uncontested collective symbols.”Footnote 10

The latter, post-1945 part of this story constitutes the basis of the established Volkswagen narrative in Germany. This narrative rests on the assumption of a clear-cut cultural dissociation between the post- and the pre-1945 Volkswagen. Yet, how could the Volkswagen in the 1950s so successfully come to symbolize the new, post-fascist Germany, while it started out being so closely connected to the Germany of the Third Reich? Within the framework of interpretations developed in recent decades to better understand postwar West German history, it is far from obvious how to address this question. Neither the rise of consumer culture and the efforts to establish a viable democracy, nor the persistent reality of Nazi penchants, Volksgemeinschaft mentality, and the dominant memory culture of German victimhood suffice as interpretive schemes to grapple with the challenges this question raises.Footnote 11 Few scholars have brought up the problem lurking behind this question, namely the relationship between the political meanings of mass consumption under Nazism and during the early Federal Republic.Footnote 12

As an iconic commodity, the Volkswagen epitomizes this problem in a unique way. Until this day, it embodies Germany's successful transformation from the rubble of the Third Reich into a consumer-democratic model of the West. Yet, how did this transformation from the Volkswagen's meanings during the Third Reich to its postwar status as political symbol take place? The success of this transformation entailed burning down the bridges which we would need to properly see its genesis. Making a genesis invisible in turn is how “miracles” come into being. Material from the margins is needed to better understand the historical emergence of Germany's “miracles.” Trying to get the Volkswagen joke means confronting the ghosts lurking behind the trope of “miracles” that worked to make them invisible.Footnote 13

How many Jews fit in a Volkswagen? In her introduction to the volume Miracle Years, historian Hanna Schissler mentions that she and other historians of her age remember a version of the joke from their childhoods in 1950s West Germany.Footnote 14 In the early 1980s the American anthropologist Alan Dundes and the German ethnologist Thomas Hauschild collected the Volkswagen joke together with other so-called Auschwitz jokes in the city of Mainz and published their findings in an English journal.Footnote 15 To publish these anti-Semitic jokes in German they had to overcome their own reluctance as well as their tendency to minimize the scope of what they first thought to be “a marginal phenomenon” but eventually identified as a common linguistic practice in Germans’ daily lives.Footnote 16

In 1983, the theater-maker George Tabori gave the Volkswagen joke a central function in his play Jubiläum (“Jubilee”), which premiered in Bochum on 31 January 1983, the fiftieth anniversary of Hitler's rise to power to which the title “Jubilee” refers. The main characters are ghosts of dead people who are all either victims of the Nazi regime or of postwar National Socialist attitudes.Footnote 17 As they talk about their suffering, they expose the ways in which the Nazi past and its afterlife still haunt German society. The Volkswagen joke is uttered three times during the play, tormenting three of those characters.Footnote 18 It is a central motif that serves to enact on stage the presence of the Nazi past in West German everyday life. George Tabori was born in 1914 into an assimilated Jewish family in Budapest and had lived in Germany since 1968. His father had died in Auschwitz.

How did the joke work and what can it tell us about the Volkswagen? The joke takes the car that has become a symbol of postwar West Germany and links it to the group of Jews, the very people that the Federal Republic's predecessor polity, the Third Reich, had set out to annihilate. How many Jews fit in a Volkswagen? Why ask this question? Would Jews fit differently in the car than other people? The first part of the answer is a surprise, the number of Jews is much higher than the spatial dimensions of the Volkswagen would allow. The second part of the answer resolves the surprise by, first, reducing the number to the usual five and by, second, transforming the remaining Jews from living human passengers into the dead material of ashes that perfectly fits in the car's ashtray.

From a psychological perspective one could say that the joke manages anti-Semitic aggression and feelings of superiority as well as a German consciousness of the Holocaust—possibly accompanied by feelings of shame. Following psychological and sociological theories of humor, it seems appropriate to assume that the Volkswagen joke, when it “works,” releases those impulses and feelings, which are usually repressed due to a social taboo, into their expression in the form of laughter.Footnote 19 But this effect requires that the joke builds and dissolves a tension through some form of witty joke-work. In this case, the joke-work is constructed around the Volkswagen. The Volkswagen joke, as any joke, uses the tension between the normal and the forbidden. It evokes something that was well-known and recognizable and at the same time unspeakable. The joke does not only connect the mass murder of the Holocaust directly to the object of this specific car. More importantly, it expresses the broken relationship between Germans and Jews through the object of the Volkswagen.

Such a reading, however, seems to contradict the existing Volkswagen historiography as well as all those stories about and images of the car that were widespread in West Germany after 1948. We are used to detecting in these images and stories the following messages: The production and export success of the Volkswagen turned Germany into a once again accepted, even respected member of the Western world. Its ubiquity on West German streets marked the end of postwar misery and the beginning of economic recovery. For millions, the car represented the promise of a better life. It epitomized feelings of freedom and the joy of driving through West Germany's rebuilt cities and idyllic landscapes, of going on a weekend trip with the family, or even of traveling to foreign countries. The Volkswagen imaginary, in short, made Germany a radiant modern society, for which the past of the lost war became almost as elusive as a bad dream, or as unoffending as a challenge that was successfully overcome.

How do all those well-known meanings of the postwar Volkswagen relate to the past of a Germany re-modelled as a racial community? How do they relate to the past of a greater German Reich that, as Alon Confino has convincingly argued, was imagined in many ways as “a world without Jews” long before it put this imagination into the practice of mass murder?Footnote 20 The postwar success of the Volkswagen represents, both in collective memory and in historiography, the development of West Germany into a Western, consumer-oriented society.Footnote 21 But something is missing from this story that has never been seriously addressed.Footnote 22

By using the joke and an advertisement as my entry points to follow the traces of the ghostly in texts and images about the Volkswagen, a different meaning of the car during the years between 1945 and 1960 has come to the surface. This meaning was both obvious and not obvious at the same time, similar to what Michael Taussig has named a “public secret,” defining it as “that which is generally known but cannot be articulated.”Footnote 23 Although “public secrets” can emerge in many forms, their characteristics match what scholars of material culture have claimed about the specific ways in which material objects become culturally significant. Due to their durability in time and their physical presence in space, material objects can be invested with a highly affective quality that differs from the significance of immaterial symbols. Concrete objects derive their meanings both from linguistic and visual discourses about them just as well as from the bodily interactions between people, places, and objects.Footnote 24 In this way a material object can incorporate conflicting and contradictory meanings without difficulty.Footnote 25 In other words, it lends itself to creating a silent presence of that which is generally known but cannot be articulated, next to, and possibly contradicting, that which is generally known and can be articulated. The Volkswagen, this mass-produced material object, was the vehicle in which millions of postwar Germans imagined driving away from their past. But they were also driving “debris” from the Nazi empire.Footnote 26 The presence of this “imperial debris” was made invisible and transformed into ghostliness through the postwar trope of (consumer) miracles, inviting us to further explore the post-fascist and postcolonial cultural conditions of postwar Western dreamscapes of consumption.

GENEALOGY OF AN ADVERTISEMENT

A Volkswagen advertisement was published in August 1960 in the high-brow cultural magazine magnum (image 1) The text says: “Young people—‘critical generation’—chrome-sparkling catchwords and mere promises have ceased to impress them already long ago. They try to find the meaning behind the things, they ask—and expect clear answers, they calculate—and expect a reasonable, reliable value. Young people (of every age) examine the Volkswagen—and then drive Volkswagen again and again.”Footnote 27 The photo shows a group of young people inspecting the Volkswagen from different angles. The text presents the young generation as rational consumers who choose the Volkswagen for its reliable value for money. The ad gives the already existing meaning of the Volkswagen as a symbol of West Germany's economic recovery a twist by associating it with an informed approach to things that is necessary for a functioning democracy. It shows the Volkswagen as a central element of the new, economically successful, and democratic West German society. Germans’ capability to dispassionately scrutinize and subsequently choose the Volkswagen becomes proof of the vehicle's good quality. Or is it the other way around? Does the ad promote the quality of the car, or does it promote the quality of the German people?

Image 1. Volkswagen advertisement, published in Magnum 31 (Aug. 1960). © Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft.

These young people are different than people used to be, the text tells us, because “chrome sparkling catchwords and mere promises have ceased to impress them already long ago [my emphasis].” This sentence clearly evokes a change of mentality. The “long ago” leaves the earlier mentality in a foggy past, but in order to make sense the reader probably had to assume that this past was situated prior to May 1945. The text therefore conveys the idea that choosing the Volkswagen implies choosing a different Germany than the Germany of the Nazi past.Footnote 28 The image, however, seems completely situated in the timeless presence of a rational modernity. Or does it? This effect appears in a different light when we juxtapose the photo with a series of other photos from 1938 and from the following years of the Nazi regime's intensive propaganda for the Volkswagen, or “KdF-car” as it was also called after the Nazi leisure time organization “Strength through Joy” (Kraft durch Freude).Footnote 29 A group of people surrounding and examining the Volkswagen was a standard motif of that campaign, starting with the presentation of the first small model to Hitler by Ferdinand Porsche in 1938 (image 2), and continuing with photos of the public presentation of test cars all over Germany in the subsequent years (image 3). These are the images of a German people that was developing a “KdF-car psychosis,” as the Social Democratic opposition put it in one of their clandestine reports in 1939.Footnote 30

Image 2. Adolf Hitler receives a Volkswagen model for his forty-ninth birthday. © bpk/Heinrich Hoffmann.

Image 3. Volkswagen in front of Sanssouci palace in Potsdam, 1938, photographer: Scherl, 28 Sept. 1938. © Süddeutsche Zeitung/HH.

A different interpretation of the advertisement now becomes plausible. The advertisement stages the car as an object that manifestly ensures the transformation of a society into a democracy by latently calling to mind its totalitarian past. The iconographic effect thus appears powerful not although there is this second layer of meaning, but precisely because of it. The question is: If the Volkswagen's success in the early Federal Republic had all been about leaving behind the Nazi past, why would the Volkswagen company in the year 1960 have had any interest in publishing an advertisement whose text, even if implicitly, conjured up precisely this past?

The car had obtained a sacrosanct status as a national symbol in the course of the 1950s. This status reached a peak three months after the Allied occupation of West Germany officially ended, when the production of the millionth Volkswagen was celebrated with great pomp at the factory in Wolfsburg on 5 August 1955. Yet, in 1957 and in 1959 a curious thing happened. The Volkswagen was attacked in prominent periodicals. Less than a year before the magnum ad, Der Spiegel, the most important political magazine in West Germany, started a full-blown offensive against this popular German symbol.Footnote 31 The magazine's cover story consisted of a long interview with Heinrich Nordhoff, director of the Volkswagen plant.Footnote 32 Under the headline “Is the VW outdated?” the interviewers confronted Nordhoff with their conviction that the existing Volkswagen model, with its streamlined body and bug shape, was decidedly behind the times. Nordhoff pointed to the commercial success of the Volkswagen as his main argument against such critique.

As the interview goes on endlessly about technical details, there is a mismatch between this matter-of-fact content and the journalists’ aggressive expressions of dissatisfaction with the car. But then, there is one short moment, appearing out of the blue, like the “strange accidents” that can be associated with instances of defacement,Footnote 33 when the journalists of Der Spiegel articulate a very different form of discontent: “DER SPIEGEL: The automobile, as it is now, is, one could say, a homunculus, an artificial creation after a socio-political model, we all know after which one.”Footnote 34 Nordhoff agrees with the claim, but pushes it away by saying, “This is not important in this context,” that it is “history,” that they should stay “with the matter itself.”Footnote 35

In this passage, a problem comes to the surface that was obviously difficult to express openly, namely the perception that, together with the Volkswagen, something of the spirit out of which it was born remained present. The Volkswagen embodied a “homunculus,” an artificially created human being stemming from the Nazi past. As they try to argue that this past is still relevant, and problematically so, for the present Volkswagen, the journalists break an unwritten rule. Nordhoff strives to reestablish the threatened division between past and present. The public secret—“we all know after which one”—is not to be spoken about.

It had, however, already been written about. In 1957, the illustrated magazine Der Stern published an article by Alexander Spoerl, also under the title “Is the VW outdated?”Footnote 36 “The Volkswagen,” the author stated, “has long ceased to be an automobile. It is a catchword. Yet, in everything that has to do with “Volk,” concepts are dangerous.” By complaining about how difficult it had become to say anything critical about it, Spoerl denounces the sacred status of the car. He formulates his own critique by presenting the Volkswagen as having an unusual “father”: “His mother was a very sound construction idea. His father was faith,” namely the “unflinching faith” of the Germans who believed the promises of the Third Reich. The words “unflinching faith” are put in quotation marks to identify them as Nazi language.Footnote 37

In order to capture the true Nazi meaning of the car, a joke is told about a worker in the Volkswagen factory of the Third Reich who stole all the pieces of the KdF-Car to put them together at home. When his friend asks why he still hasn't assembled the car, he answers: “However I screw together the parts, it never becomes a car, but always a cannon.” These cannons, Spoerl claims, were in reality Volkswagen, namely the military Volkswagen-Kübel which is then presented as an anthropomorphic entity living through recent German history: “The VW-Kübel became the most loyal comrade of the German soldier. Afterwards he was the first ‘war criminal’ to be de-Nazified. He put on the Limousine again, the occupying soldiers fell in love with him, Wolfsburg received steel and the license for reconstruction. His off-road construction and the front-line experience made him well-suited for the slightly uneven postwar Germany. That is how he acquired his steadfast reputation.”Footnote 38 Spoerl crossed the line of the usually unsaid by identifying the Volkswagen and the enthusiasm attached to it with the Germans’ “faith” in the Nazi movement and its promises. The article apparently caused a great stir, as references to it in automobile magazines indicate. Yet, the resulting discussion focused solely on the technical aspects and left the political dimension in the realm of the unsaid.Footnote 39

This is the context in which we must read the cover story interview in Der Spiegel. It is also the context in which we should place the magnum advertisement. In 1957, Spoerl had exposed the public secret in an explicit and witty effort to desecrate the holy status of the Volkswagen. In 1959, the interview in Der Spiegel showed both a consciousness of the exposed secret and the impossibility of consistently naming it. Yet, in 1960 it was apparently sufficiently exposed to publish an advertisement which both evoked it and at the same time covered it up with another layer of meaning in order to make it disappear again.

These three examples are the most outspoken ones among occasional expressions of discomfort about the car and the unmanageable presence of its Nazi past, occurring often in the form of humor and irony, both in journalistic writings and in some of the advertisings for the Volkswagen during the 1950s.Footnote 40 In 1952, a Volkswagen advertisement stated: “What has made [the Volkswagen] well-known and popular, what has made it the top-selling and much sought-after German car is not its history of origins, but the harmony of its technical and economical features its value as a utility vehicle without unnecessary and expensive freight [my emphasis].”Footnote 41

The Volkswagen's history of origins that this ad explicitly tried to push away consisted first and foremost of the massive propaganda campaign which the National Socialists had organized to promote the Volkswagen and which had continued even during the war. According to historian Paul Kluke, writing in 1960, the Nazi Volkswagenpropaganda had a “magic effect” and the success of that campaign “nearly” turned the Volkswagen into a “symbol of National Socialist propaganda technique” and “of the blind confidence of all German social classes.”Footnote 42 This campaign had produced the “chrome-sparkling catchwords and mere promises” that resonated so deeply into the postwar era that the postwar “critical generation” had to be declared immune to them in the magnum advertisement that was published in the same year as Kluke's analysis.

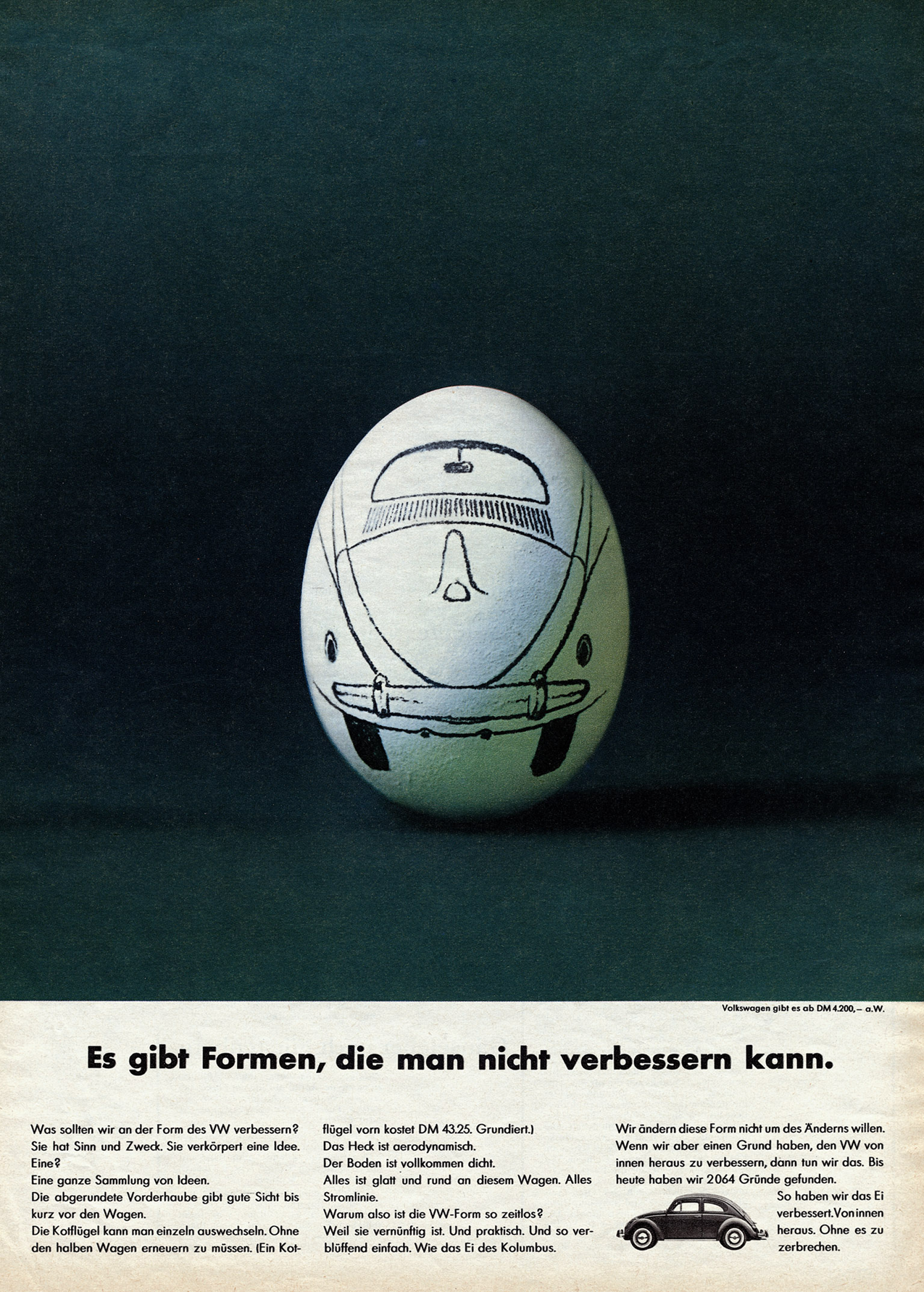

Taken together, the three examples discussed above make it possible to expose to a certain extent the workings of the public secret. Spoerl and the journalists of Der Spiegel expressed an uneasiness with what the Volkswagen silently embodied in the German public sphere and thereby tried to expose the secret and undermine its untouchable status. The 1960 ad implicitly referred to this uneasiness in a way that arguably paved the way for a conversion of the postwar public secret into something ungraspable for the younger generation. In 1962, Volkswagen started its first big ad campaign in the postwar German press with the German branch of the New York agency “Doyle Dane Bernbach” that had promoted the VW in the United States since 1959.Footnote 43 Against the background of the growing discomfort about the Volkswagen at the end of the 1950s, the DDB campaign of the early 1960s can be interpreted as implicitly addressing the criticism that the car would be outdated (image 4).

Image 4. Volkswagen advertisement, “Es gibt Formen, die man nicht verbessern kann” (Some shapes are hard to improve on), published in Der Spiegel and Hörzu, 16 Dec. 1962. © Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft.

The brilliant irony and humor of the campaign broke with the dominant forms in which the car had been promoted during the 1950s. It thereby prepared the car's appropriation by a younger generation. The campaign brought about what the magnum ad of 1960 had already attempted, namely lifting the perception of the car out of its still present but usually subliminal implication in the Nazi project. It thus managed to transform the car's public secret of the 1950s into a different form of secret, one that encapsulated information about the early postwar period that was henceforth not “generally known” anymore. It thereby arguably generated a cultural condition of aphasia for younger Germans. The public secret and the attempts to unveil it during the 1950s spoke above all to the older generation. Younger Germans who had never directly been exposed to Nazi propaganda, Volkswagen or otherwise, were less able to properly “get” such coded messages.Footnote 44 The 1962 campaign then started a process of rebranding that was largely successful given the subsequent absence of critical discussions about the postwar symbol's relationship with the Nazi era.Footnote 45 What this process eventually left in its wake were ghostly matters in the form of nearly unreadable traces in the archive.

DRIVING THE VOLKSWAGEN THROUGH SPACE AND TIME

What were the narratives, metaphors, and images used in the postwar period that may have incited such expressions of discomfort about the Volkswagen? And what can those cultural scripts tell us about the hidden meanings of the car that eventually transformed into ghostly apparitions? When Spoerl identified the car with the German man in Der Stern, he took up an existing narrative. Already in 1949, the car magazine Motor-Rundschau presented the vicissitude of the Volkswagen since 1938 as the story of a young man named “Vinzenz.” This identification of the car and the German man through the change of times implied a physical continuity of both that included as one and the same car the Wehrmacht's Volkswagen, the Kübelwagen. During the war, Vinzenz the Volkswagen “proved himself as a loyal comrade and served in France, Russia, and Africa. Neither the cold in the east nor the heat in the desert sand harmed his primordially healthy constitution.”Footnote 46 The Kübel seemed to enable the idea of a continuous existence of the Volkswagen through the change of times and, eight years later, Spoerl ironically criticized exactly this idea and its implications.

This common conflation of Volkswagen, Kübelwagen, and the German man directly counteracts the notion that the Volkswagen was a symbol of a new beginning and harks back to an heroic image of the Nazi war, an image closely associated with the conquering of geographic space.Footnote 47 The postwar habit of describing the Volkswagen Kübel as a “loyal comrade,” of insisting that it was essentially the same car as the civilian Volkswagen and of conflating it with the German soldier, stemmed directly from Nazi propaganda. From May 1941 onwards, the magazine Arbeitertum, the nationwide organ of the German Labor Front, used the name “KdF-Car” or “Volkswagen” interchangeably for the military Kübelwagen that had just demonstrated its quality through its successful services for the German Africa corps.Footnote 48 In an article from March 1942 car and driver merged into one: “Quickly advancing to the enemy, versatile in combat,” the Volkswagen was even more resilient than the German soldier. He conquered “the wide snow fields of Russia” and “the stony deserts of destroyed Soviet cities” as well as he resisted “North Africa's glittering sun.”Footnote 49

Already in December 1940, an Arbeitertum cover article reiterated the promise that after the war “every German worker will own his Volkswagen and drive on German highways from Klagenfurt to Narvik. […] the German worker will not have to deal with time and space—due to his social status he will own the world!”Footnote 50 This Nazi propaganda envisioned the postwar experience of owning and driving a Volkswagen as a form of conquering time and space. The promise that the “Volkswagen” would be available for every “German worker” came with the promise of a new (European) order under German leadership, including greater social equality within the racially defined “Volk.” The car functioned as a medium to imagine this future world in a concrete way: The German worker would drive his Volkswagen on the German Autobahn through the expanded German Reich, from the Austrian Klagenfurt to the Norwegian Narvik. Driving the car meant belonging to the German people, being part of the “people's body,” and—dominating the world.Footnote 51

Traces of this envisioned future were still alive in the postwar imagination. The car transported the past's dream of the future into the postwar present. Yet, as the previously discussed articulations of discomfort indicate, the transition of these Nazi fantasies about the Volkswagen into the postwar presence was not self-evident. Indeed, it required a mythology. Such a mythology was delivered in 1951 when the young author Horst Mönnich published his first novel, Die Autostadt. It became an immediate success, selling more than a hundred thousand copies.Footnote 52 Mönnich's novel is the most sophisticated and explicit postwar attempt to re-narrate the story of the Volkswagen. In 1968, Mönnich, a former Hitler youth and soldier during the war, summarized his 1945 moment of disillusionment with the question: “But where […], if this, in which we had wrongly believed, had never been Germany—where had Germany then been?”Footnote 53 His novel's answer was: the real Germany had been contained, and had survived, in the form of the Volkswagen and in the form of the city and factory that produced it.Footnote 54 Volkswagen director Heinrich Nordhoff praised the book in his foreword to the first edition as uncovering “truths” that “lie deeper than the visible, that touch the true core of events.”Footnote 55

The text orchestrates the experiences of the German population during the Third Reich, the war, and its aftermath by looking through the prism of the Volkswagen, the factory, and the city. Like a force of nature, the machines, the factory, the streets, and the buildings of Wolfsburg form the glue that binds together all the different German characters from all regions of the former German Reich, many of them refugees. Large parts of the novel use organic metaphors to describe a mystic link between the people, the place, the factory, and the car: the organization of the city is compared to a human organism, the factory is “a being that has an autonomous life” which, together with the German workers, engenders another living being: the Volkswagen.Footnote 56

The novel's transcendental worldview of organic wholeness ties in with many elements of Nazi culture and is reminiscent of what Jeffrey Herf has called “reactionary modernism.”Footnote 57 It is the dream of a society without social differences, a redeemed organic entity realized through the workings of a soulful and animated technology embodied miraculously in the Volkswagen. Die Autostadt is, at its core, a founding myth that makes sense of Germany's historical rupture by presenting the Volkswagen as an object with magical qualities. The car that is repeatedly referred to as “the miracle” ensures the postwar resurrection of a West Germany rising from the ashes and ready to bring about its postwar economic recovery.Footnote 58 The military Volkswagen Kübel plays a key role in enabling this mythical transformation.

The section dedicated to the Kübel's war exploits marks the transition from the car's and the city's Third Reich history to their new postwar life. While the car is depicted as a living being with superhuman capacities, the identity of the Kübelwagen, the Volkswagen, and the German soldier becomes an important element of the Volkswagen's transfer to the postwar world.Footnote 59 The object of a rotating globe frames scenes that gradually display the various theaters of the German war of expansion. The moment of defeat is captured in the form of a burnt down Volkswagen followed by the standstill of the globe. This zero moment of standstill contains the seed of rebirth: The sun shines its light exactly on the place which will induce the car's and the people's resurgence, namely the city in the North of Germany where the Kübelwagen was produced and where the civilian Volkswagen will follow in its military brother's footsteps, conquering the world once again, this time as a commodity. The novel presents the beginning postwar mass production and export of the car as filling a void created at the dark hour of Germany's war defeat. The “miracle car” enables German superiority, seemingly destined for the dustbin of history in 1945, to transform itself from its military manifestations into its civilian form of international trade relations.Footnote 60 The text thus uses the notion of a “zero hour” in combination with the Volkswagen as an enchanted commodity to create a myth that was meant to ensure cultural continuity.

How did this novel relate to the Volkswagen imaginary available in the German public sphere? The official Volkswagen advertising in West Germany, limited in general, was characterized by a lack of innovative elements that could have clearly separated the meaning of the car from its Nazi legacy.Footnote 61 Volkswagen's most important advertising activity during the decade after 1949 consisted of producing and disseminating promotional films.Footnote 62 Most of these films, especially until the middle of the decade, used an audio-visual language that continued the aesthetics of the Weimar and the Nazi Kulturfilme. Footnote 63 If the Nazi educational films “infused” the avant-garde cinema of the 1920s “with new ideological meanings,” these Volkswagen films in turn transported many elements of this Nazified aesthetics into the postwar era.Footnote 64 The most important of them, “Aus eigener Kraft” (“From one's own strength”) from 1954, is a symphonic film in Agfacolor that stages city life, factory buildings, assembly line production, and industrious workers as a natural, flowing process of matter and bodies that magically engenders this hugely successful car “from” the people's “own strength.”Footnote 65

The film performs an identification of the Volkswagen and Germany through two maneuvers: On the explicit level, the Volkswagen appears as a phenomenon floating in the timeless space of an ideal modernity, disconnected from both its Nazi past and the concrete conditions of its early postwar relaunch. On the implicit level, the film stages the transfiguration of the car's industrial production into a constitutive element of an organicist model of society, thereby continuing a connection of the Volkswagen to National Socialist fantasies of social harmony, racial exclusivity, and German superiority. This combination of the outspoken and the silent generates, again, the mythical character of this miracle story about the people's and the car's regeneration.Footnote 66

While the film celebrates the expansion of Volkswagen's export, the images and the language used to tell this civilian story call to mind the imperial tropes used by the Nazi campaign for the Kübelwagen. At the end of the film, the finished car rolls from the assembly line onto the streets and the narrator captures the moment with pathos: “Here, finally, he can touch the earth. The earth has him and he has the earth, the whole wide earth for himself.” Earlier postwar Volkswagen films had staged how the car conquers the globe in a similarly emphatic way. The ending of the 1949 film “Symphony of a car” showed Volkswagen rolling out of the factory followed by rows of VWs on a train and then a shot from a highway bridge on an endless line of VWs on the autobahn (image 5). In the last—animated—sequence, the viewer sees a globe from afar with Germany roughly in the middle, while an endless number of Volkswagen cars are streaming out of Germany, toward the viewer and into outer space (image 6).Footnote 67

Image 5. Screenshot, “Sinfonie eines Autos,” Germany 1949, UKA Film-Produktion, directed by Ulrich Kayser and Werner Liesfeld, © Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft.

Image 6. Screenshot, “Sinfonie eines Autos,” Germany 1949, UKA Film-Produktion, directed by Ulrich Kayser and Werner Liesfeld, © Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft.

GENESIS OF A MIRACLE

The connection between the Volkswagen and a National Socialist body politic was a cultural phenomenon that left many traces in the archive. They can be found on the margins, on those occasions when an uneasiness about this connection was expressed. They can also be found in the way rhetoric and aesthetic patterns were continued after 1945. The mismatch between these findings and the meaning of the Volkswagen as symbolizing a West Germany that was defined away from its own past must have created an interpretive void, or, psychologically speaking, a cognitive dissonance. The concept of the “miraculous” seems to have filled this void by smoothing over the intrinsic cultural contradictions of how Germany's Western reconstruction happened.Footnote 68

Mönnich's novel about the “miracle car” was published in 1951. Around 1952, West Germans began to agree that the term “German miracle” (initially more rarely “economic miracle”) was suitable to describe the development of their country after the currency reform.Footnote 69 As a phrase that encapsulated the whole process of West Germany's postwar reconstitution, the “German miracle” redirected attention away from the concrete occurrence of cultural transformation, especially from those dissonant parts which undermined the coherence of the narrative. Referring to the economic boom and the Volkswagen's as well as other German commodities’ success as a “miracle” both acknowledged and brushed aside the unlikeliness of a new West German identity built on these phenomena.Footnote 70

In order to understand the genesis of the Volkswagen as this kind of “miracle,” we have to revisit the postwar process of cultural transformation from a different angle. As Peter Fritzsche put it, “the idea of Germany had been covertly Nazified as well as Aryanized” after January 1933.Footnote 71 National Socialism's total war defeat and the loss of state sovereignty resulted in a deep crisis of identity, a collectively shattered “unconscious self-confidence.”Footnote 72 This experience followed a twelve-year period of extreme collective self-aggrandizement at the expense of the Third Reich's proclaimed enemies and the racial community's “others.” Before the war, an excess of national symbols, rituals, and other aesthetic materializations constantly provided the presence, and thereby an experienced reality, of these ideas in the public sphere. After the war, the state of Germany's national non-existence was reflected in the destruction of some of these symbols by the allies and their subsequent absence from the public sphere in which a different sovereignty ruled.Footnote 73

A crisis of identity, a world view in shambles, and the resulting disorientation play out above all on the level of affects and emotions. In the German case, this crisis was necessarily intensified by the allies’ efforts to de-Nazify the population by confronting them with their collective responsibility for the mass murder committed in their name.Footnote 74 Collectivities need narratives and symbols to make sense of themselves. An individual's sense of self also depends on the acknowledgment he or she receives from other human beings. On the level of a society this entails being recognized by other countries. After Germans had embarked on coercing such “recognition” or “respect” from other nations through the brutal force of war and mass crime, they suddenly found themselves at the mercy of how the world in general and the occupation forces, in particular, looked at them. The gradual genesis of the Volkswagen as a national symbol of West Germany is inextricably entwined with such dynamics of real or imagined external perceptions and the affects evoked by them.

To get a better grip on how the Volkswagen became the symbol of the postwar “economic miracle,” it is useful to pay attention to the affective sensibilities emerging around this object in journalistic discourses from the years of allied occupation onward. Any object's symbolic power derives from the affects it is able to provoke, affects which may spring from more complex narratives and interpretations and at the same time contain these (possibly contradictory) narratives in a condensed form.Footnote 75 If we follow the car in this way through its random occurrences in the press, the emotional reactions around the Volkswagen can roughly be summarized as a journey from resentment to pride.Footnote 76 Focusing on the expression of these kinds of emotions throws a sharp light on how the object of the Volkswagen served to mediate and embody the changing relationship between (West) Germans and the occupation forces as well as the Western world outside of Germany.

The first Volkswagen to come off the assembly line in 1946 and 1947 were not available for Germans, but were nearly exclusively delivered to the occupation forces.Footnote 77 Thus, in the initial period, the car that the Nazis had previously made into a symbol of the imperial German postwar order of affluence had fallen into the hands of Germany's former enemies. The earliest appearances of the Volkswagen in the press testify to a complicated constellation of sensibilities linked to this situation. In August 1947, Der Spiegel reported on the preparation of the export exhibition in Hannover, mentioning twenty-five new Volkswagen deployed as official taxis. The road traffic department had issued a special decree for this occasion in order to prevent “that the taxis would only be entered by foreigners full of calories and nicotine.”Footnote 78 In January 1948, Jan Molitor wrote in Die Zeit about the celebration of the twenty thousandth Volkswagen. The disappointment of the workers that the car is only available to the occupation forces is a central theme of the article. Summing up their frustration, Molitor reports: “‘The Volkswagen?’ the workers say. ‘The car runs and the people watch from the outside.’”Footnote 79 The mood is not celebratory due to the workers’ bitterness about the war defeat caused by Hitler, and to their disappointment about the foreign sovereignty over, as well as exclusive use of, the newly fabricated Volkswagen.

The currency reform, however, marks a clear break with this early period of heightened resentment surrounding the postwar status of the car. After the production of the Volkswagen had increased and the car became available both for export and for German customers,Footnote 80 the most dominant theme in the press became the success of the car outside of Germany. In October 1948, Quick printed a photo of a Volkswagen on the Dam square in Amsterdam with a caption stating that “our small Volkswagen” could be found on every street corner in Holland. Two weeks later another photo showed American workers at the port of Hamburg admiring a Volkswagen as a “nice little car.” This tendency culminated in May 1949, right after the founding of the Federal Republic, with a headline on the big success of the German Industry fair in New York and a photo of the Volkswagen surrounded by admiring visitors.Footnote 81

That the specter of national shame could still loom large behind the new spectacle of national pride became apparent in a report on the same event in the magazine Neue Illustrierte. Here, the photo of the admired Volkswagen was placed beneath an equally large one showing a picket line of protesters in New York carrying banners with slogans such as “We don't want soap manufactured from Jewish bodies,” and “Boycott this Nazi show.” In the caption the magazine informed its readers about another slogan, namely “Today People's Car—Tomorrow Death Car.”Footnote 82 The reader was thus confronted with the fact that presenting German commodities, and especially the Volkswagen, in a city with a large Jewish community was not self-evidently generating enthusiasm, but rather brought to the surface a reminder of the close connection between German industrial production, in particular of this car, and the mass murder of Jews.Footnote 83

Der Spiegel's first cover story on the Volkswagen, from May 1950, established the image of the car as an epitome of West Germany's regained power and authority as well as an important source of national pride. The first paragraph set the tone by citing a Life magazine story in which the Volkswagen was presented as a “symbol of German ‘Reconstruction’ [English in the original]: Symbol of the sturdy German proficiency.”Footnote 84 American experts in New York, American soldiers in Hamburg, Dutch customers in Amsterdam, and many more foreigners enter the stage in 1948, 1949, and 1950 to affirm again and again to German readers that there are good reasons to be proud—of the Volkswagen in particular, and of West Germany's steps toward economic and political recovery in general. Taken together, these examples indicate that the perception of how Germany was seen from the outside fulfilled a crucial, if not decisive role for the Volkswagen to emerge as the quintessential object of postwar national pride and as the symbolic center of the evolving miracle narrative.

What kind of perceptions from the outside were available to Germans in this period? Der Spiegel's remark about Life referred clearly to the latter magazine's photo report on West Germany from 1949 entitled “Recovery in the West.” The report gave special attention to the Volkswagen with a full-page photo showing rows of Volkswagens in front of the factory in Wolfsburg.Footnote 85 This story, however, is merely one reflection of a much larger effort from the outside to reinterpret Germany's position in the world. Between 1948 and 1952, the Marshall Plan propaganda campaign, “the largest international propaganda operation ever seen in peacetime,”Footnote 86 accompanied the European Recovery Program (ERP) all over Europe. This campaign in many ways established the most important features of the new postwar political imaginary of the West. As Sheryl Kroen's recent work makes clear, the campaign staged the event of Western Europe's “recovery” based on the principles of free trade, productivity, and international cooperation.Footnote 87 In the context of this endeavor Germany, the author of Europe's postwar crisis, was rebranded as a West Germany without history, a new entity rising out of the rubble, a model country of Western production and export whose inhabitants were praised for their “almost fanatical reverence for toil.”Footnote 88 This process of rebranding culminated on the occasion of the 1950 Berlin Industries Fair, which was broadcast around the world.Footnote 89 In the exhibition, Germany's official appearance as national entity happened in the form of a hand-drawn figure named “Herr X.” The exhibition showed “the transformation of Herr X—from a soldier in uniform, marching, producing destruction, annihilation and extermination all over Europe, into a hard-working, vital participant in the recovery, wearing a new suit.”Footnote 90

West Germans appropriated this Marshall Plan story of Germany's recovery and turned it into a popular narrative of national regeneration. In the emerging West German version, the Western Allies were relegated to the sidelines, from where they were acknowledged as shouting approving remarks that confirmed a recuperated German self-confidence. Even before the term “German miracle” came into use, the 1948 currency reform was already labeled “the great miracle.”Footnote 91 But it was not only the abundance of commodities suddenly filling German stores that were perceived as a “miracle.” The greatest miracle for postwar West Germans was the recognition of their country as a vital member of the Western community in the context of the emerging Cold War.

“One should not accuse a person of the bad manners of his past,” wrote the magazine Motor-Rundschau in 1949 about the Volkswagen. “Now, after the currency reform, the great miracle, he appears spick and span, with really good manners and therefore: young man from a good family.”Footnote 92 Herr X, and his anthropomorphized mirror-image, the German Volkswagen, were not marching any more. Although the war was mentioned in this article as an experience that had shaped the Volkswagen's—or the German soldier's—character in a positive way, the Western framework of “the recovery” instilled a different meaning into the same narrative, one that could eclipse the fact that the “good family” the article evoked may have been uncomfortably interwoven with the Third Reich's racial community.

HAUNTING MIRACLES

In the course of this article I have spun together the different knots of the marginal and uncanny popping up in the archive around the Volkswagen and I have tried to knit them into a connected, but necessarily not altogether coherent, web of readings. A physical activity like knitting is perhaps a fitting metaphor for the work needed to understand “the ‘unexpected capacity of objects to fade out of focus’ as they ‘remain peripheral to our vision’ and yet potent in marking partitioned lives.” Stoler aptly uses Daniel Miller's words to get to the core of what the study of “imperial debris” means. “Imperial formations,” she writes, are defined by racialized relations of force. Their “political forms … endure beyond the formal exclusions.” After the imperial formation has officially ended, much of its “rot” remains, which defies the clear demarcation between before and after. Material objects become the carriers, “peripheral to our vision,” of the still ongoing past. “Imperial debris” disobey a totalizing notion of continuity and rupture. They can only be “debris” because something has become past. They can only assert their power because something is still present. But they remain also, in spite of all their cultural force, a fragile phenomenon, an “ungraspable moment.” Or rather, their force is in part due to the very fact that they “fade out of focus.”Footnote 93

Between 1946 and 1962, the Volkswagen became a sacrosanct national symbol of Germany's postwar “miracles” through its capacity to silently transcend the 1945 divide. That capacity derived from the fact that it was not merely a symbol. The Volkswagen became a mass-produced material object that could be perceived and experienced as an embodiment of an organic German body politic. The car was associated with dreams of a harmonious and superior racial community, it was linked to the desire and experience of belonging to an invincible people's body, and it combined promises of timelessness with imperialist fantasies of conquering and dominating exoticized geographical space. The Volkswagen could keep something alive that was supposed to be dead. It could bridge the gap between the Germany before and after 1945. It could do all this, not although, but because it could simultaneously be the opposite, namely an innocent technical commodity, driving into the future and fading out of the political observer's focus.

How many Jews fit in a Volkswagen? Was the question meant as a provocation when it was asked during the 1950s? At the very least, the question must have reminded Germans of the fact that the postwar Volkswagen was different from the Volkswagen promised before 1945. Jews were now allowed to enter and drive it, something that was certainly never intended by the Nazi regime.Footnote 94 Telling the joke, in any case, assumed a laughing audience of Aryan Germans. It thereby performed, and repeated, a cultural practice of exclusion and dehumanization. As a speech act the joke painfully gives linguistic presence to the mass murder that had been the result of precisely the kind of body politic that the Volkswagen had silently continued to manifest after the war.

Paying attention to the uncanny has proved to be a helpful methodological tool for exposing rarely acknowledged meanings of this powerful icon of postwar West Germany and by extension postwar modernity. It has enabled me to identify as a “ghost” a personal memory of the joke and an archival encounter with an advertisement that seemed to make no sense. Experiencing the ghostly aspects of these apparitions has meant to recognize their unique characteristic of lingering in a limbo between past and present, disrupting the usually unproblematic separation between a “then” and a “now,” a disavowed and objectified past and a present that is owned as one's own. This is what makes the postwar Volkswagen an “imperial debris,” a manifestation of a disorienting and therefore haunting cultural formation.Footnote 95

Postcolonial studies scholars have started to resort to the notion of haunting in order to grasp the ongoing presence of the colonial past after the formal end of empire, the bewildering ways in which “the complex colonial legacy [is] still circulating in and between former imperialist centers and their peripheries.”Footnote 96 Homi Bhabha's text “The World and the Home” (1992) has played an influential role in these conversations. Bhabha declared the “unhomely” and the haunting “a paradigmatic post-colonial experience.”Footnote 97 Whereas the ghostly can also be approached as an object of study, in the context of postcolonial studies the concept is used in particular to reflect on how the confusion about the relationship between past and present bears on those who study the past.Footnote 98 The case of the Volkswagen as an “imperial debris” speaks to this latter dimension and encourages us to think about postwar West Germany as a postcolonial society shaped by the unruly presence of a double colonialist past.Footnote 99 The image of a Volkswagen whose “healthy constitution” could neither be “harmed” by “the cold in the east nor the heat in the desert sand” is a reminder of the manifold entanglements between Germany's earlier colonial presence outside of Europe and the Nazi version of a colonial project on European grounds, entanglements that are the object of recent academic debates and a growing body of historical scholarship.Footnote 100

While “imperial debris” have mostly been identified in former colonies, the concept applies here to a metropolitan culture after empire.Footnote 101 The Volkswagen as a postwar symbol emerged fully after, as Robert Young has put it, Europe's “own postcoloniality with respect to the Nazi empire was instituted.” The process to formally end the imperial regimes of the other European countries, however, took much longer, thereby producing a long-lasting “postcolonial condition” and carving out the terrain in which “imperial debris” can still haunt the present.Footnote 102 Yet, the “ruination” of social relations that the Volkswagen carried into the postwar present was hidden behind and within its “miraculous” existence as a timeless commodity.

This Volkswagen story, then, is not only about ghosts, but also about miracles. The car did not only haunt West German society as unspeakable debris of the Nazi empire, but it also enchanted postwar West German society as the symbol of the “economic miracle.” Ghostliness turns up in relation to that which society “knows and does not know”Footnote 103 about itself and which it therefore cannot articulate. The trope of the “economic miracle” can be defined as a collective myth, a story about an improbable and therefore wonderful occurrence that society willfully identifies with. In the case of the Volkswagen, the ghostly and the miraculous belong together. The Volkswagen and the miracle that it embodied exemplify an enchantment that is about un-seeing the ongoing presence of a disavowed past and turning it into something that is hidden in plain sight yet never properly graspable.

Is this configuration of the ghostly and the enchanted limited to the Volkswagen case and to the “economic miracle” of West Germany? The previous paragraph has indicated the extent to which the Volkswagen “miracle” was imagined as a global phenomenon by West Germans and how this imagination was enabled through a transnational, and especially transatlantic production of meaning. We should think of it, therefore, as a piece in a larger transformation of the political and cultural framework during the formative postwar years between 1945 and 1960. During these years the notion of the “West” as a cultural-geographic sphere binding together societies with a common history, a “modern” culture, and liberal political norms became dominant.Footnote 104 At the same time, free trade and a Taylorist emphasis on productivity were promoted intensely in the context of the Marshall Plan as the definitive formula to solve Western Europe's social, economic, and political problems. Part of this endeavor was to imbue the resulting consumer objects with a socially and politically redemptive, or miraculous, quality. Considering both of these newly established frameworks of meaning as well as their interdependence is important to understanding how the Nazi Volkswagen could reemerge as Germany's favorite “miracle car.”

The emergence of the idea of the “West” at the beginning of the twentieth century was closely and ambiguously intertwined with the history and legacy of European imperialism.Footnote 105 Both the focus on the Cold War framework and the acceptance of the 1945 divide, which usually accompanies it, have dominated scholarly interpretations and collective memory to such an extent that the ramifications of imperialism and colonialism on the postwar histories of Western societies are still far from being fully understood. This is particularly true regarding consumer culture and the postwar “modern.” The relationship between the political dimensions of postwar consumer cultures and the previous colonialist and fascist politicization of the commercial sphere—during high imperialism, the interwar period, and World War II—has only recently become a topic of historical scrutiny.Footnote 106 The same holds true for the racial dimensions of U.S. postwar consumerism as well as for the connections between the imaginaries of postwar European consumer cultures and the context of decolonization.Footnote 107

The influence of postcolonial studies is now felt strongly all across the discipline of history, not the least in the debates about “modernity” as a guiding concept.Footnote 108 An increasing awareness of the problems engrained in the concept of “modernity” and its naturalized connection to “the West” seems to open up a space to develop new perspectives also for the postwar period. Meanwhile, and on a par with the latter, scholars have begun to study different forms of “enchantment” as a significant, if not constitutive, part of not only non-Western but also Western cultures of modernity.Footnote 109

The enchantment of mass-produced commodities as markers of a modern and Western way of life formed an indispensable ingredient of postwar political imaginaries. French intellectuals, in particular, were puzzled and fascinated by what they saw as the overdetermination of consumer objects in their time.Footnote 110 Roland Barthes’ call to examine the “decorative display” in popular culture of the “what-goes-without-saying” strongly influenced the rise of cultural studies in the following decades. Although Barthes stated in his “Mythologies” that every myth “transforms history into nature,” he himself refrained from studying the myths of his own time historically by tracing their genesis back in time.Footnote 111 The ghostly aspects of the Volkswagen's meanings in West Germany teach us that if we are to expand our understanding of the powerful consumer myths and miracles of the postwar period in the West then we need to closely study their concrete emergence in time and in a—not yet—postcolonial space. To pursue this, we need genealogies that systematically bridge the 1945 threshold and we need to develop an awareness of the possible effects of haunting, including on us as scholars.Footnote 112

When Aimé Césaire reflected in 1955 about what the experience of Nazism meant for his contemporaries, he stated provocatively that Europe and the whole of “Western” civilization experienced it as a “choc en retour.”Footnote 113 According to Césaire, Europeans recognized an aspect of themselves in the horrors of the Nazi empire, an aspect which their own frameworks of perception had rendered invisible before, yet they simultaneously hid this realization from themselves. Césaire's insight invites us to ask how postwar societies may have developed and cultivated certain forms of “colonial aphasia” specifically in reaction to the Third Reich's “choc en retour.” This might enable us to get a better handle on how the postwar economic recovery, its accompanying dreamscapes, and the symbolic role of a rebranded West Germany produced their own subcutaneous spheres of haunting.