CLINICIAN'S CAPSULE

What is known about the topic?

Despite a growing global interest in community paramedicine, there is poor understanding of the program types and training for each.

What did this study ask?

What are the different types of community paramedicine programs and the training for each type?

What did this study find?

Community paramedicine programs were diverse and collaborative, often serving 911 callers and in-home visits, and training emphasized technical skills.

Why does this study matter to clinicians?

Understanding programs and training informs areas of interest, including for emergency medicine providers, such as programming, education, and regulation.

INTRODUCTION

Community paramedicine is an emerging form of health services delivery with the potential to reduce emergency department (ED) visits among high user groups while making use of existing paramedic resources.Reference Jensen, Marshall and Carter1–Reference Everden, Eardley, Lorgelly and Howe3 There is growing interest in community paramedicine and its expansion across Canada, Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom.Reference Iezzoni, Dorner and Ajayi4 Community paramedicine extends traditional paramedic care and is staffed by emergency medical services (EMS) professionals often with additional training.Reference Pang, Liao and Litzau5 Programs can be tailored to community needs by providing a range of services, including disease management, home assessments, and referral to community services.Reference Agarwal, McDonough and Angeles6, Reference Brice, Overby, Hawkins and Fihe7

Community paramedicine programs may lead to more effective use of paramedic resources. In some programs, paramedics on accommodated duty have adopted the community paramedic role while awaiting return to regular duties.Reference Agarwal, McDonough and Angeles6 Community paramedicine responsibilities have also been incorporated into the downtime between emergency calls.Reference Smeby8 Community paramedicine may support more efficient use of healthcare resources by increasing collaboration between different healthcare providersReference Abrashkin, Washko and Margolis2 and facilitating patients’ access to appropriate home and community services.Reference Agarwal, McDonough and Angeles6

Despite expanding upon the paramedicine role, many countries have no professional education standard for community paramedicine – Canada being one of them. Training for community paramedicine usually varies by program or region. In Ontario, the provincial government regulates the qualifications and roles of only paramedics providing ambulance services, not those of community paramedics. Furthermore, provincial legislation in Alberta, Saskatchewan, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick has allowed paramedics to be a self-regulated profession.9, 10 Identification of common services and roles across community paramedicine programs will inform future discussions on community paramedicine education standards and professional regulation. The Canadian Standards Association's (CSA) community paramedicine framework for program development, which details types of community paramedicine programs, is a start.11 Discussion on the future of community paramedicine in Canada is also informed by recommendations on paramedicine scope of practice and direction from leading organizations in the paramedicine sector, including the EMS Chiefs of Canada and the Canadian Organization of Paramedic Regulators. In 2006, the EMS Chiefs of Canada published The White Paper, which outlined the strategic direction for EMS in Canada, including a focus on interprofessional collaboration.12 The Canadian Organization of Paramedic Regulators aims to be a collective voice for paramedic regulators and to support the development of paramedicine in Canada. Key pillars in sector development identified by the organization include intersectoral collaboration and leveraging evidence to assess and further paramedics’ professional competencies.13

Despite community paramedicine growth, the current community paramedicine landscape, types of programs and their purpose, and the training required for each program type remain poorly understood.Reference Bigham, Kennedy, Drennan and Morrison14, Reference Choi, Blumberg and Williams15 This information may guide development and evaluation of new programs, facilitate resource pooling between jurisdictions, and support regional planning for community paramedicine programs. Knowledge of community paramedicine training required to support different types of programming may also inform the direction of the community paramedic profession. A systematic review was conducted to 1) identify the key differences between community paramedicine programs for program classification, and 2) describe the training required for each program type.

METHODS

Study type

A systematic review was conducted according to Cochrane methodology. The full methodology is available on PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42017051774)Reference Chan and Agarwal16 and is summarized below. Systematic review methods were chosen because the research questions were specific and well defined, and the included studies could be assessed for quality.Reference Arksey and O'Malley17 In contrast, scoping reviews generally have broader research questions, and quality assessment of included studies is often not done.18

Research questions

1) What are the key differences between community paramedicine programs for program classification?

2) What is the training required for each type of community paramedicine program?

Data sources and search strategy

MEDLINE and Embase databases were searched to identify all relevant articles published up until January 22, 2018. Keywords from frequently cited community paramedicine articles were used with advice from experts and research librarians. The keywords reflect the most preliminary conceptualization of community paramedicine, that is, it involves paramedics providing services in a community setting. The strategy combined terms from three themes: 1) paramedicine and paramedics, 2) community setting, and 3) synonyms for community paramedicine such as CP and Mobile Integrated Healthcare (MIH). The MEDLINE search strategy [((theme 1 terms combined with OR) Emergency care practitioner*.mp., Paramedic*.mp., Paramedical personnel.mp., Para medical personnel.mp.) AND ((theme 2 terms combined with OR) Community care.mp., Community.mp., Communities.mp.)] OR [(theme 3 terms combined with OR) Community paramedic*.mp., Mobile integrated healthcare.mp., Mobile integrated health care.mp., MIH-CP.mp., Community paramedicine program*.mp.] – was mirrored for Embase. Additional articles were identified by hand-searching bibliographies and grey literature searches for programs identified in included articles, and by community paramedicine experts.

MEDLINE and Embase databases were selected because, through preliminary searching of the literature, it seemed that most of the published literature would be captured in these databases. Recognizing that a lot of programs are described in the grey literature, additional hand-searching of bibliographies and grey literature searching were completed. Grey literature searching was done through a targeted Google search using the names of community paramedicine programs and any other identifying information (e.g., location of program) referenced in the screened articles. The types of grey literature materials included government and community reports, newspaper articles, and poster presentations.

Inclusion criteria and selection process

All articles describing community paramedicine programming were included regardless of study design, setting, population, or outcomes. Non-English articles were excluded. Title and abstract (Level 1) and full-text (Level 2) screening of the published articles were completed in duplicate by two independent reviewers (JC, GA). Grey literature sources were also screened in duplicate by two independent reviewers (JC, GA). Cohen's kappa coefficient (κ) was used to measure inter-rater agreement. Data extraction for the published and grey literature sources was completed in duplicate by independent reviewers JC and GA. All discrepancies were resolved by discussion or consultation with a third reviewer (AC or LG).

Primary outcomes extracted for the published and grey literature sources were locations of community paramedicine visits (e.g., home visit), patient populations (e.g., 911 callers), target conditions addressed (e.g., diabetes), method of patient enrolment (e.g., referral from healthcare provider), interprofessional team members (i.e., who work with the community paramedic), community paramedicine services provided (e.g., acute care), health outcomes assessed (e.g., transport to ED), and community paramedicine training, including training subjects, provider, and duration. Excel spreadsheets were used to organize the screening and data extracted from studies identified in the published and grey literatures.

Study quality assessment

The 2011 version of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used to evaluate the methodological quality of included studies with one of five study designs (qualitative, quantitative randomized controlled, quantitative non-randomized, quantitative descriptive, and mixed methods). The MMAT has been used in over 50 systematic reviews worldwide and is reliable and content validated.Reference Pluye, Robert and Cargo19 Other study designs (e.g., literature reviews) and articles with no study design (e.g., only described the program) or results (e.g., protocol) could not be assessed by the MMAT.

RESULTS

Part I. Search yield

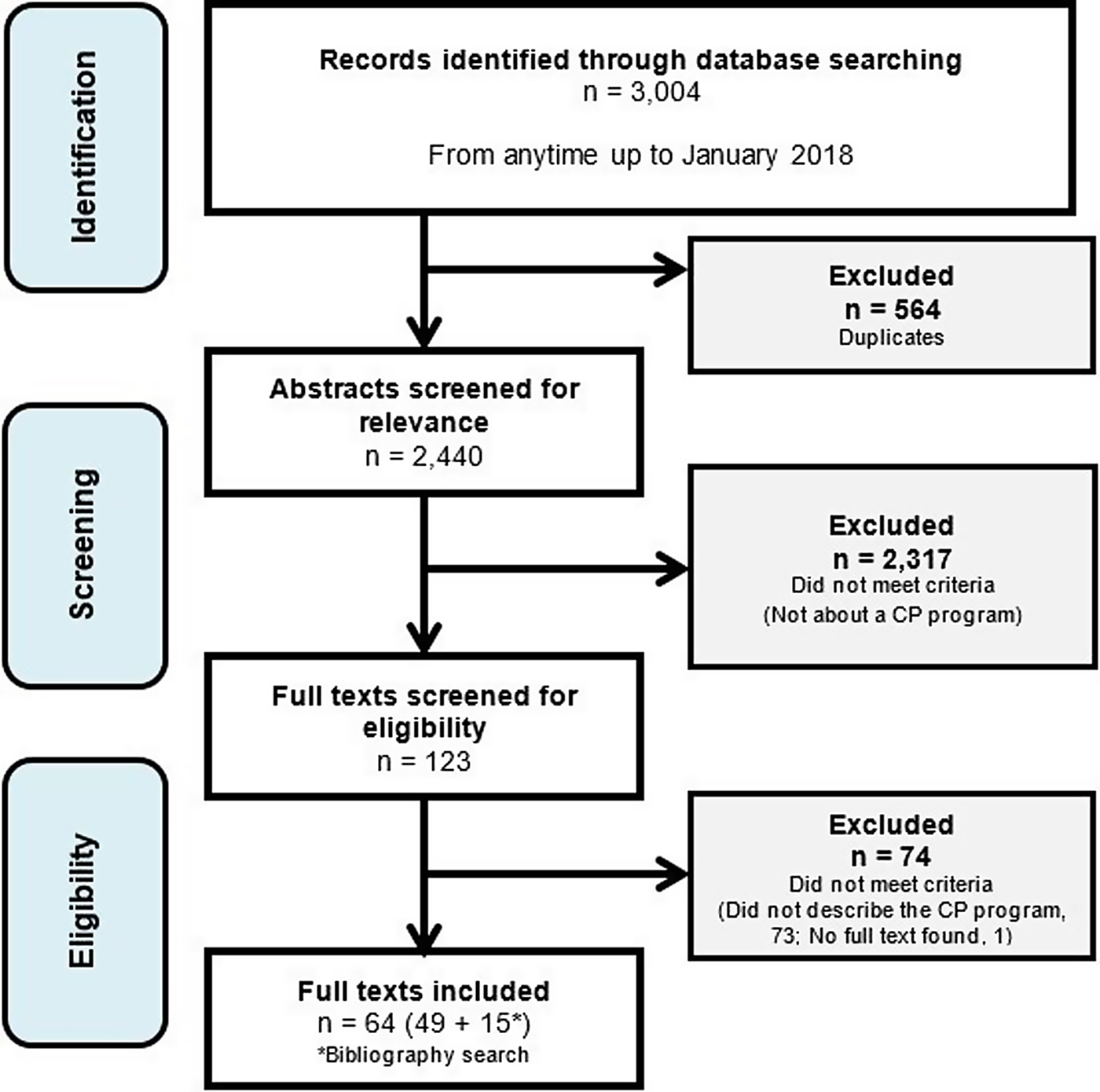

The search identified 3,004 articles, and, after screening and searching bibliographies of included articles, a total of 64 studies representing 58 unique community paramedicine programs were included (Figure 1).Reference Jensen, Marshall and Carter1,Reference Abrashkin, Washko and Margolis2, Reference Everden, Eardley, Lorgelly and Howe3, Reference Agarwal, McDonough and Angeles6, Reference Brice, Overby, Hawkins and Fihe7, Reference Abrashkin, Washko and Zhang20–Reference Harrison78

There were 15 (23.4%) of the 64 studies identified by hand-searching the bibliographies of included studies and by follow-up grey literature searching, and 14 (24.1%) of 58 community paramedicine programs captured were identified through the grey literature (see online Appendix for the table of included studies and grey literature sources).

Figure 1.

Of the 64 studies, 29 (45.3%) studies had a defined study design and 35 (54.7%) described the program only. Of those with a study design that could be appraised using the MMAT, 6 were quantitative randomized controlled studies (e.g., randomized controlled trial [RCT]), 11 were quantitative non-randomized (e.g., case-control, cohort), 8 were quantitative descriptive studies (e.g., incidence/prevalence study without comparator), and 4 were mixed methods studies (e.g., cluster RCT with qualitative interviews). The MMAT was applied to the 26 studies (3 studies were protocol only); the median score was three stars, or three of four criteria met, suggesting moderate quality. Levels 1 and 2 screening were completed in duplicate. The raw agreement and kappa coefficient for L1 pilot (n = 200) were 94% and 0.78, respectively, and 95% and 0.42 for L1 total (n = 2,804). For L2 pilot (n = 11), they were 73% and 0.42, respectively, and 100% and 1.00 for L2 total (n = 112).

Part II. Features of the 58 community paramedicine programs captured

Location of community paramedicine visits

All 58 programs stated the community paramedicine visit location, with most operating through home visits only (70.7%). There were 46 (79.3%) urban area programs and 7 (12.1%) in rural areas only (Table 1).

Table 1. Location of community paramedicine visits*

* Categories are non-exclusive (i.e., a program can have more than one visit location).

Patient populations

The target population of 28 (48.3%) programs was emergency callers (e.g., called 911 or were frequent 911 callers), and there were 24 (41.4%) programs for individuals at risk for ED admission or readmission, or hospitalization. Overall, seven (12.1%) programs were solely for older adults living in the community or long-term care (LTC) homes (Table 2).

Target conditions and patient enrolment

The majority of community paramedicine programs (n = 39; 67.2%) did not target a specific health condition. Among those that did, diabetes mellitus was common (n = 6; 10.3%), followed by heart failure (n = 5; 8.6%) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n = 5; 8.6%). An emergency call initiated patient enrolment in 22 (37.9%) programs; in 11 (19.0%) programs, clients were referred (e.g., by a provider, social worker, family); and clients voluntarily enrolled in 6 (10.3%) after receiving an invitation or hearing about the program.

Interprofessional collaboration

In 45 (77.6%) programs, community paramedics collaborated with at least one other professional: nurses, including nurse practitioners (n = 11; 19.0%), family doctors only (n = 3; 5.2%), primary care teams, which may have included family doctors (n = 4; 6.9%), pharmacists (n = 4; 6.9%), and social workers (n = 7; 12.1%).

Services provided

The types of services provided included assessment and screening, acute care and treatment, transport and referral, education and patient support, communication, and other (Table 3). Most common were physical assessment (n = 27; 46.6%), medication management (n = 23; 39.7%), and assessment, referral, and/or transport to community services (n = 22; 37.9%).

Health outcomes assessed

Health outcomes were extracted per study instead of per community paramedicine program because different studies of the same program evaluated different health outcomes. Of the 64 studies, 13 (20.3%) did not report any health outcomes. The most commonly reported health outcomes included transport to ED (n = 23; 35.9%), hospital admission (n = 21; 32.8%), and 911 calls (n = 12; 18.8%). Other patient outcomes assessed were adverse outcomes (n = 7; 10.9%), clinical improvements or changes (n = 10; 15.6%), healthcare utilization (non-ED, n = 8; 12.5%), medication adherence (n = 3; 4.7%), non-healthcare resources utilization (n = 3; 4.7%), patient satisfaction (n = 11; 17.2%), and treated on-scene (n = 4; 6.3%).

Part III. Features of community paramedicine training: Subjects, providers, and duration

Training components of the 58 community paramedicine programs were acute care, assessment and screening, care of specific populations, education and health promotion, special knowledge, as well as communication and leadership. Training components were not described by 25 programs (43.1%, Table 4). There were 25 (43.1%) programs that described the training provider(s), where 6 (10.3%) involved a university (e.g., school of medicine), 9 (15.5%) involved healthcare professionals (e.g., care of elderly specialists), and 4 (6.9%) involved a college (e.g., technical college). Community services and representatives, hospitals, and public health departments were involved in two programs (3.4%) each. Only 22 (37.9%) community paramedicine programs provided clear information about the training duration; the median training time was 240 hours per trainee per program with a range of 3.5 to 2,080 hours.

Part IV. Additional analyses: Community paramedicine services and training subjects by population

Among the 28 community paramedicine programs that targeted 911 callers, the most common services provided were physical assessments (n = 15; 53.6%), acute care (n = 12; 42.9%), and transport to ED or urgent care centres (n = 10; 35.7%). The most common training subjects for these 28 programs were acute care (n = 7; 25.0%), intervention-specific materials (n = 7; 25.0%), health management (n = 6; 21.4%), comprehensive health assessment (n = 6; 21.4%), and knowledge of community services (n = 5; 17.9%).

Among the 24 community paramedicine programs for individuals at risk for ED admission, readmission or hospitalization, the most common services were medication management (n = 14; 58.3%), followed by physical assessment, acute care, education, and communicating with the patient's healthcare provider(s) in 9 (37.5%) programs each. For these 24 programs, the most common training subjects were health management (n = 8; 33.3%), providing acute care (n = 6; 25.0%), medication management (n = 6; 25.0%), knowledge of community services (n = 5; 20.8%), and how to care for seniors (n = 5; 20.8%).

Among the four community paramedicine programs for seniors living in the community (not facility), the most common services provided were physical assessments and assessing, referring, and/or transporting to community services with each provided by three (75.0%) programs. The training for these programs usually covered how to care for seniors; assessing the environment (e.g., home), health risks, and overall health; health promotion; and intervention-specific materials (n = 1 each; 25.0%).

DISCUSSION

In this comprehensive systematic review, the 58 community paramedicine programs evaluated were very heterogeneous in the populations they served and their outcomes captured. The community paramedicine training required to implement these programs was often sparsely described, if at all. Among the handful of existing literature reviews about community paramedicine,Reference Pang, Liao and Litzau5, Reference Bigham, Kennedy, Drennan and Morrison14, Reference Choi, Blumberg and Williams15 none described the key differences between community paramedicine programs and the training for each. The present systematic review captured many community paramedicine programs and described program training and services by population.

The diversity of community paramedicine roles and services has allowed community paramedics to address a variety of health and related community needs, as recommended by the CSA standards.11 Services associated with paramedicine, including acute care, physical assessment, and transport to the ED or urgent care centre, were part of the services and training for many community paramedicine programs captured. Commonalities between paramedicine and community paramedicine services may indicate that paramedics are in a good position to adopt the community paramedicine role because they already have some of the relevant skills. Community paramedicine expanded upon traditional paramedic duties, clientele, and interprofessional collaboration. Community paramedicine programs also provided education, counselling, coaching, health promotion activities, and in-home visits. In addition to serving 911 callers, commonly paramedicine clientele, many community paramedicine programs served individuals at risk for ED admission or readmission or hospitalization. Working with clients before their need for ED or hospital care demonstrates the unique role of community paramedicine in providing preventive and upstream care. Diverse and expanding roles and services for paramedics, as observed in the community paramedicine programs captured, reflect a broader innovative approach by the paramedic sector to support community needs. The innovation and evolution of paramedicine models of care to better meet community needs align with the recommended direction for paramedicine in Canada developed by the EMS Chiefs of Canada.12

Only a handful of community paramedicine programs reported seniors as their sole target demographic and/or provided training on caring for senior populations. The number of community paramedicine programs serving seniors is likely underestimated because seniors are often present in other demographic groups targeted, including frequent 911 callers and ED users. For example, in a systematic review of ED use in the United States, frequent users were more likely to be between the ages of 25 and 44 or age 65 and up.Reference LaCalle and Rabin79

The general understanding of community paramedicine as being paramedics with additional training in health prevention and promotion did not capture the observed spectrum of community paramedicine services and training. As demonstrated in this review, community paramedicine expands upon traditional paramedicine training and services, in that paramedics receive additional training to provide services that address immediate and anticipated health, social, and other needs – not just acute and emergent needs. This definition of community paramedicine aligns with the standard on community paramedicine program planning developed by the CSA in 2017 where community paramedicine programs were described as providing a spectrum of immediate and scheduled care to vulnerable patients to improve equity in healthcare access.11 There is also alignment with the International Roundtable on Community Paramedicine which viewed community paramedicine as the application of paramedicine skills and training, often with an expanded scope of practice (i.e., outside emergency transport and response), in community settings.9

Adding to these definitions, community paramedicine is also shown here as a highly collaborative profession, because the majority of community paramedicine programs captured involved interprofessional collaboration and connected clients to other providers and community organizations. Interprofessional collaboration is not only a key characteristic of programs captured in the present review, but also, more broadly, may be contributing to overall improved community paramedicine program and sector outcomes. The EMS Chiefs of Canada propose that collaboration between EMS and community organizations (e.g., different healthcare providers and social services) enables the development of innovative initiatives that support improved healthcare in a community.12 Furthermore, the Canadian Organization of Paramedic Regulators identifies that collaboration enables the paramedicine sector to adapt more effectively to changes in scope of practice and regulation.13

The majority of community paramedicine training described in this review, however, seemed to be centred on technical skills such as acute care, assessment, and screening. The expanded activities, roles, and collaborations of community paramedics further underline the value of common and standardized community paramedicine training for relevant skills such as communication, teamwork, and leadership. Although standard paramedic training may already address skills such as communication, the diversity of community paramedicine services and roles emphasizes the value of more specialized community paramedicine training in the areas noted.

Despite this, the diversity of professional backgrounds captured among providers of community paramedicine training – such as public health, community services, and healthcare – may have contributed to community paramedics developing a more holistic understanding of community partners and services. Community paramedicine training may also have been a platform to clarify roles and interactions between community paramedics and other providers, and may have supported the day-to-day interprofessional collaboration observed in many community paramedicine programs. Role clarity has been shown to support optimized integration of providers into new healthcare settings and teams.Reference Brault, Kilpatrick and D'Amour80 Ensuring role clarity for community paramedics, such as scope of practice and responsibilities, within the interprofessional context may support integration of community paramedicine and effective interprofessional collaboration.

Among the programs that reported on training, most did not use regionally mandated standardized training, with the exception of programs based in Minnesota (United States) where community paramedicine certification followed a customizable state-wide curriculum.81 The overlap in subjects taught in community paramedicine training, especially among those programs serving the major community paramedicine target populations, may indicate core competencies for community paramedicine. The development of a common community paramedicine education framework could be informed by these core competencies.

A strength of community paramedicine programs was how roles and services were responsive to a variety of health and related community needs. The diversity of community paramedicine programs, however, has also made it challenging to develop a specific single role description for community paramedicine. As a result of community paramedicine serving diverse target populations and providing various services, community paramedicine training was often developed at the program-level and tailored to these factors, rather than standardized across programs. A standardized educational framework for community paramedicine would need to capture the core competencies required, but also allow for program-level customization to include a growing spectrum of community paramedicine competencies. The community paramedicine programs captured in this review often did not report training subjects and/or outcomes, and none described paramedics’ training success and confidence in becoming a community paramedic. The limited knowledge of what was effective and ineffective for community paramedicine training is a considerable barrier to developing an evidence-informed community paramedicine education framework.

In order to facilitate discussion around standardized training or certification of the community paramedicine profession, there needs to be an adequate information “bank” about community paramedicine programs and training. The resources and capacity must be available for community paramedicine programs to undertake rigorous evaluation of program and training outcomes and to disseminate findings. There must also be expert input, such as from established community paramedicine programs, education institutions, professional bodies, the public, and other stakeholders, when determining the core components of community paramedicine training to inform any community paramedicine education framework.

In the United Kingdom, for example, the Health and Care Professions Standard (HCPS) regulates the paramedicine profession and has developed standards to regulate and approve education programs; HCPS has not developed comparable standards and regulations for community paramedicine.9 In the United States, many states have passed a legislation to enable and define community paramedicine practice, and determine education or licensing.82 The regulatory and legislative work in other jurisdictions may guide similar efforts in Canada. By presenting an overview of community paramedicine program types and training for each, this review starts to clarify the information available about community paramedicine and provides a basis for further discussion on program development, training, and education. Particularly, for the Canadian context, valuable next steps include a sub-analysis of Canadian community paramedicine programs and identifying the differences in paramedicine competencies, training, and regulations between Canadian programs and those globally.

Strengths and limitations

Limitations include that not all community paramedicine programs were captured, although the review did cover grey literature. Not all community paramedicine programs are described in the published and grey literatures, and resource limitations prevented more extensive grey literature searching (e.g., running a full Google search using a defined search strategy instead of the targeted Google search of community paramedicine program names and identifiers). Study heterogeneity prevented the meta-analysis of the top three health outcomes (i.e., 911 calls, transport to ED, hospitalization). For example, community paramedicine programs that measured the same health outcomes had vastly different population groups or were protocol only. Comparing community paramedicine programs and training was further challenged by absent or inconsistent reporting. Fewer than half of the studies captured had a defined study design, and the other studies described only the program services and population, and generally without outcome measures. Varied data reporting and the limited ability to pool and compare studies may reflect the current state of community paramedicine. The field is growing and evolving to diverse community needs, as evidenced by the breadth of community paramedicine programs captured. Community paramedicine programs also have differing capacities to measure and report program descriptors and performance.

In the present study, the kappa coefficients suggested only moderate inter-rater reliability (κ = 0.41–0.60).Reference McHugh83 As κ is influenced by event prevalence,Reference Mandrekar84 the low κ observed could have been caused by low study inclusion during screening. Piloting screening and extraction forms, plus resolving discrepancies through discussion, supported inter-rater reliability. However, despite these limitations, this review is a comprehensive and up-to-date reflection of community paramedicine programs and reported training.

CONCLUSION

The systematic review identified 58 unique community paramedicine programs with a wide range of target populations and services. Community paramedicine training, although poorly reported, was equally diverse and included a variety of skills that were unique from the traditional paramedicine role. The highly collaborative nature of community paramedicine may warrant more training on related skills such as communication, leadership, and teamwork. Effective implementation and growth of community paramedicine may also be aided by clearer definitions of the community paramedicine role. Furthermore, enabling community paramedicine programs to gather and disseminate evidence on training and program outcomes may better inform community paramedicine education frameworks and support program growth.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2019.14

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the several librarians at McMaster University and St. Michael's Hospital who provided guidance on the systematic review search strategy.

Financial support

This work was supported by a graduate studies research stipend through the Master of Public Health Program at McMaster University. Otherwise, this research received no specific grant or award from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Competing interests

None declared.