Introduction

Co-morbidity in mental health diagnoses, defined here as the presence of features in an individual’s experiences that could result in the person’s presentation meeting the diagnostic criteria for more than one psychiatric diagnosis at any given time, is a matter of increasing interest in the research and treatment of mental health conditions. Whilst theoretical models of co-morbidity exist, they are limited in the range of presentations they are applicable to and are typically presented in a complex manner inappropriate for use in clinical practice with service users and colleagues unfamiliar with psychological constructs. The current paper presents a novel formulation model for use in clinical practice, which is grounded in empirical evidence and is uniquely applicable across mood, psychotic and eating presentations. Furthermore, the formulation offers explanation as to how behavioural change has the potential to cause harm in the delivery of psychological therapy unless transdiagnostic behaviours are attended to in treatment.

Psychological treatment of co-morbidity

As part of a national co-morbidity study conducted in the USA, Kessler et al. (Reference Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas and Walters2005) found that whilst 55% of those meeting criteria for a mental health diagnosis only held a single diagnosis, 23% held more than three. Evidence of frequent co-morbidity has further been demonstrated in an online study by Al-Asadi et al. (Reference Al-Asadi, Klein and Meyer2015), in which diagnostic criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edn, text rev., DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) were assessed in 12,665 participants. The study found rates of co-morbidity inclusive of both males and females as high as 83.7%. The study not only offers further evidence of high rates of co-morbidity but also posits support for the use of a transdiagnostic approach to the assessment and treatment of mental health presentations.

Despite the evidenced frequency of co-morbid presentations, cognitive behavioural conceptualisations of mental health presentations on which talking therapies are based have traditionally developed diagnosis-specific models: theoretical conceptualisations that differentiate mental health presentations on the premise that there are distinctive features that maintain each. For example, there exist different cognitive models for depression (e.g. Westbrook et al., Reference Westbrook, Kennerley and Kirk2007), panic disorder (Clark, Reference Clark1986), bipolar disorder (Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Mansella, Morrison, Reid, Lowens and Tai2007), generalised anxiety disorder (Wells, Reference Wells1997), and persecutory delusions (Freeman, Reference Freeman2016) to name a few. Whilst there is evidence that diagnosis-specific cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) is an effective treatment for a variety of presentations (Hofman et al., 2012), rates of remission (50% in people with a diagnosis of anxiety disorder: Springer et al., Reference Springer, Levy and Tolin2018) and relapse (53%: Ali et al., Reference Ali, Rhodes, Moreea, McMillan, Gilbody, Leach, Lucock, Lutz and Delgadillo2017) suggest there are triggering or maintaining factors that are not addressed sufficiently in diagnosis-specific approaches. Furthermore, the evidence for these talking therapies has been criticised for the exclusion of co-morbidities in many randomised controlled trials (RCTs; Fortin et al., Reference Fortin, Dionne, Pinho, Gignac, Almirall and Lapointe2006) despite high levels of co-morbidity being evidenced, although recent guidelines for managing this threat to external validity in trials have emerged (O’Hara et al., Reference O’Hara, Beaudreau, Gould, Froehlich and Kraemer2017). It is therefore arguable that conceptualisations offering explanation of how these co-morbidities interact and maintain one another are necessary to effectively understand and treat the distress experienced by people with co-morbid presentations. Furthermore, evidence from trials investigating diagnosis-specific CBT interventions have shown that there are sometimes secondary improvements in co-morbid symptoms (Kiropoulos et al., Reference Kiropoulos, Klein, Austin, Gilson, Pier, Mitchell and Ciechomski2008; Sensky et al., Reference Sensky, Turkington, Kingdon, Scott, Scott, Siddle, O’Carroll and Barnes2000). One explanation for secondary gains from diagnosis-specific interventions is that there may be a common underlying mechanism that is being treated, thus improvement in both presentations is evident from a targeted intervention. However, this finding is not consistent, with others reporting no improvement in secondary outcome measures (e.g. Stjerneklar et al., Reference Stjerneklar, Hougaard, McLellan and Thastum2019).

Transdiagnostic processes

Alongside the evidence for the high incidence of co-morbidity and evidence demonstrating improvement in secondary outcomes is literature demonstrating the presence and relevance of processes that are evident across a variety of presentations. Transdiagnostic processes have been described as ‘the cognitive behavioural processes identified as important across the different psychological disorders’ (Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Watkins, Mansell and Shafran2004; p. 1), and may comprise cognitive, emotional and/or behavioural factors. For example, there is evidence to suggest that emotion regulation (Sloan et al., Reference Sloan, Hall, Moulding, Bryce, Mildred and Staiger2017), repetitive negative thinking (McEvoy et al., Reference McEvoy, Watson, Watkins and Nathan2013; Wahl et al., Reference Wahl, Ehring, Kley, Lieb, Meyer, Kordon, Heinzel, Mazanec and Schonfeld2019), psychotic experiences (van Os and Reininghaus, Reference van Os and Reininghaus2016) and experiential avoidance (Fernández-Rodríguez et al., Reference Fernández-Rodríguez, Paz-Caballero, González-Fernández and Pérez-Álvarez2018) are all processes that may be implicated in a range of diagnostic presentations. Consequently, the very concept of diagnostic specificity itself has been called into question in recent literature (Dalgleish et al., Reference Dalgleish, Black, Johnston and Bevan2020).

Two transdiagnostic behaviours that have been implicated across presentations and subject to substantial investigation are rumination and avoidance. Rumination has been conceptualised as a broader concept than repetitive negative thinking, encompassing any repetitive thought regardless of emotional valence: ‘Obsessional thinking involving excessive, repetitive thoughts or themes that interfere with other forms of mental activity’ (American Psychiatric Association, 2019). Rumination has been implicated across mental health presentations, typically in relation to rumination on negatively valenced self or situational thought-content (e.g. Hartley et al., Reference Hartley, Bucci and Morrison2017; Teo and Collinson, Reference Teo and Collinson2019), which has consequently been shown to be one psychological factor, along with self-blame and avoidant coping, to mediate the relationship between other known risk factors and mental health (Kinderman et al., Reference Kinderman, Schwannauer, Pontin and Tai2013). It follows logically then, that time spent ruminating on negatively valanced content would limit the opportunity for engaging in positively valenced or self-compassionate thinking, both of which have been shown to have a beneficial effect on measures of mental health symptoms (Bennetts et al., Reference Bennetts, Stopa and Newman-Taylor2020; Sommers-Spijkerman et al., Reference Sommers-Spijkerman, Trompetter, Schreurs and Bohlmeijer2018). More recently, rumination on positively valenced content and the occurrence of elevated mood states has emerged. Gruber et al. (Reference Gruber, Harvey and Johnson2009) found rumination on a pleasant memory increased positive affect, positive thoughts, and heart rate in both people with a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder and those without, although positive affect was greater in the group with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Hanssen et al. (Reference Hanssen, Regeer, Schut and Boelen2018) found people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder were more likely to ruminate on positive affect when compared with a sample with a diagnosis of unipolar depression, suggesting the transdiagnostic behaviour of rumination is implicated in the onset and maintenance of pleasant, high-arousal mood states as well as states of low arousal typically associated with mental health presentations.

The behaviour of avoidance, defined as ‘Any act or series of actions that enables an individual to avoid or anticipate unpleasant or painful situations, stimuli, or events, including conditioned aversive stimuli’ (American Psychiatric Association, 2020), has been implicated in samples comprising mood presentations (Holahan et al., Reference Holahan, Moos, Holahan, Brennan and Schutte2005), eating presentations (MacLeod et al., Reference MacLeod, MacLeod, Dondzilo and Bell2019), psychotic presentations (Tully et al., Reference Tully, Wells and Morrison2017) and anxious presentations (Hofmann and Hay, Reference Hofmann and Hay2018). As such, the act of avoidance is well accepted as a behavioural treatment target across transdiagnostic treatment protocols (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda and Lillis2006; Wilamowska et al., Reference Wilamowska, Thompson-Hollands, Fairholme, Ellard, Farchione and Barlow2010).

Transdiagnostic models

To this end, various models attempting to account for transdiagnostic processes and their mechanism in co-morbidity have been presented in recent years, primarily focusing on anxiety and depression. Clark and Beck (Reference Clark and Beck2010) propose a cognitive neurophysiological model in which the features of cognitive theory converge with neurobiological correlates to explain the emergence of both anxious and depressive symptoms. The model presents specific brain activations accompanying negative schema activation in response to environmental triggers and enduring vulnerabilities. These activations are proposed to drive inhibited cognitive control (and associated specific neurobiological correlates), which in turn drive ineffective coping and avoidance, and consequent anxious/depressive symptomology. A strength of the model is the convergence of multidisciplinary research evidence; however, this theory is limited by a lack of distinction between episodes of anxiety and depression and thus does not explain how one may move between a presentation characterised by a dominant depression to a dominant anxiety state and vice versa. Furthermore, the inclusion of complex neurobiological terminology renders the model inappropriate for use as an explanatory tool for a lay person attending therapy.

Barlow et al. (Reference Barlow, Sauer-Zavala, Carl, Bullis and Ellard2013) present a further theory concerning the emotional disorders. Positioning neuroticism, or ‘the tendency to experience frequent and intense negative emotions in response to various sources of stress’ (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Sauer-Zavala, Carl, Bullis and Ellard2013; p. 344) as the core underpinning presentation of emotional disorders, the authors also acknowledge an interactive effect with other transdiagnostic components such as negative interpretations of emotional reactions, experiential and situational avoidance, and suppressive and ruminative coping. The theory emphasises the importance of emotional reactions being experienced as aversive, and a treatment protocol derived from the theory (the Unified Protocol, UP; Wilamowska et al., Reference Wilamowska, Thompson-Hollands, Fairholme, Ellard, Farchione and Barlow2010) has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of both anxious (Farchione et al., Reference Farchione, Fairholme, Ellard, Boisseau, Thompson Hollands, Carl, Gallagher and Barlow2012) and depressive symptomology (Sauer-Zavala et al., Reference Sauer-Zavala, Bentley, Steele, Tirpak, Ametaj, Nauphal, Cardona, Wang, Farchione and Barlow2020), offering tentative empirical support. However, the theory lacks explanation as to (a) why an anxious or depressive character may dominate the presentation at any given time point and (b) how one may move between a primarily anxious to a primarily depressive presentation (or vice versa). Furthermore, as with the model proposed by Clark and Beck (Reference Clark and Beck2010), the emphasis on emotional distress does not account for how anxious or depressive episodes may interact with presentations characterised by more pleasant emotional experiences, such as hypomania in bipolar disorder. Additionally, from the point of clinical utility, there is no clearly articulated presentation of the model on which to map clinical presentations.

Other Axis I presentations

Further theories have been developed to account for the transdiagnostic processes seen within subtype categories of the DSM manuals, for example eating disorders (Fairburn et al., Reference Fairburn, Cooper and Shafran2003), bipolar affective disorder (Mansell et al., Reference Mansell, Mansella, Morrison, Reid, Lowens and Tai2007), and psychosis (van Os and Reininghaus, Reference van Os and Reininghaus2016). However, these models lack any explanation as to co-morbidities that span more than one diagnostic category, for example, both an eating and anxiety disorder, despite evidence that co-morbidities often span more than one diagnostic category (Achim et al., Reference Achim, Maziade, Raymond, Olivier, Mérette and Ray2011; Braun et al., Reference Braun, Sunday and Halmi1994; Simon et al., Reference Simon, Otto, Wisniewski, Fossey, Sagduyu, Frank, Sachs, Nierenberg, Thase and Pollack2004). Furthermore, these models are subject to a similar critique to the models by Barlow et al. (Reference Barlow, Sauer-Zavala, Carl, Bullis and Ellard2013) and Clark and Beck (Reference Clark and Beck2010), in that they are complex and academic in their presentation and thus unsuitable for use in direct clinical practice with service users.

In summary, there are a number of limitations to existing cognitive behavioural models that aim to explain co-morbidity. The transdiagnostic models of mood presentations, although spanning more than one diagnostic category, do not offer explanation as to co-morbidity with the non-affective presentations (e.g. eating or psychotic presentations) and do not account for positively valenced affective states (e.g. elated mood). Transdiagnostic models concerned with presentations other than mood are similarly limited in their ability to account for co-morbidity spanning more than one diagnostic category, and it has been suggested elsewhere that the theoretical underpinning for transdiagnostic interventions continues to require further development (Dalgleish et al., Reference Dalgleish, Black, Johnston and Bevan2020).Furthermore, whilst offering explanatory power from a theoretical perspective, each of the models considered are complex and academic in their presentations and lack an appropriate formulation template for use in clinical practice.

Third-wave models and formulations

Third-wave transdiagnostic approaches to treatment such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and compassion-focused therapy (CFT) are concerned with addressing transdiagnostic processes as opposed to the diagnosis-specific cognitive content targeted in the diagnosis-orientated CBT interventions. Although adopting a transdiagnostic approach to mental health presentations, much of the research into these interventions involves traditional symptom-based outcome methodologies. As such, these approaches are evidenced in improving symptoms in specific diagnostic populations as well as those presenting with co-morbidity (ACT: Arch et al., Reference Arch, Eifert, Davies, Vilardaga, Rose and Craske2012; Thesiko et al., Reference Thesiko, Murphy, Milnes, Lambe, Curtin and Farren2015; CFT: Frostadottir and Dorjee, Reference Frostadottir and Dorjee2019; McManus et al., Reference McManus, Tsivos, Woodward, Fraser and Hartwell2018), further supporting the concept of transdiagnostic processes as primary treatment targets. These models stipulate differing transdiagnostic maintenance factors, with ACT hypothesising psychological inflexibility as a primary maintenance and treatment target (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda and Lillis2006), and CFT hypothesising an imbalance in affect regulation systems with self-criticism and shame primary factors in maintaining a threat response (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2009).

The Hexaflex model (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda and Lillis2006) underpinning ACT incorporates a variety of internal psychological processes but also employs a systemic approach to psychopathology, with context as a key concept in this approach. However, the Hexaflex model does not explain how the component parts relate to one another or if they are equally weighted in the onset and maintenance of mental health presentations. Thus, as a theoretical model there is limited scope for testable hypotheses and empirical evaluation of the theory, outside predicting that higher levels of psychological inflexibility should result in higher psychopathology. The affect regulation model in CFT (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2009) draws on a considerable history of evidence for the relevance of biopsychosocial factors in psychopathology, and thus incorporates cognitive, biological and behavioural features, and appropriately acknowledges the simplification of complex interactions in the service of clinical accessibility. However, the theoretical underpinnings and case conceptualisations employed in these therapies arguably have drawbacks when attempting to engage service users in a collaborative case conceptualisation in clinical practice. For example, in ACT, the case conceptualisation (Bach and Moran, Reference Bach and Moran2007) and Hexaflex and Triflex worksheets (Harris, Reference Harris2019) do not demonstrate how differing features of the presentation serve to maintain each other and uses academic language that, whilst it may be clear and understandable to a therapist with the relevant theoretical knowledge, may not be easily accessible to someone not trained in psychological theory and experiencing high levels of distress. Whilst the CFT case formulation worksheet (Kolts, Reference Kolts2016) clearly cites fear and behaviours as contributing maintaining factors, and uses a diagrammatic format with explanatory arrows as to how different components relate to one another, some concepts are not intuitively worded and thus the untrained audience may struggle to identify with how, for example, ‘self to other relating’ may serve to maintain ‘internal defensive behaviours’.

The Infinity Formulation: Rationale

There are a range of models in the literature that seek to offer a theoretical explanation of co-morbidity and of transdiagnostic processes in the maintenance of mental health presentations. Additionally, there is growing evidence for the effectiveness of transdiagnostic approaches to treating these presentations. However, these models do not offer explanatory power as to how and why there is movement between primary presenting states in co-morbidity such as, for example, why anxiety may be more prominent at one time and depression more prominent 6 months later in the same individual. Furthermore, the models are complex in their presentation and are not suited for use as an explanatory tool in clinical settings due to the use of academic language that requires background theoretical knowledge inaccessible to most audiences without psychological training. Similarly, the case conceptualisation worksheets developed in transdiagnostic approaches to treatment employ complex concepts and language requiring considerable translation to a lay audience, and do not easily offer explanation of how a presentation may both shift between primary problems and yet be maintained by over-arching transdiagnostic processes.

The Infinity Formulation aims to overcome the limitations of the models described by extending these approaches through an emphasis on transdiagnostic behaviours as both maintaining factors and trigger points for co-morbidity, providing a framework that is applicable both to and beyond presentations characterised by negatively valenced mood. The formulation is novel in offering explanation as to how attempts to intervene or break the maintaining cycles in bipolar presentations can serve to trigger not only manic states but also those characterised by anxiety and paranoia.

The model was developed intuitively through working with service users with whom the use of a single diagnostic nosology was not appropriate. Drawing on the existing evidence-based models described, and incorporating recent research implicating transdiagnostic behaviours in the experience of pleasant as well as unpleasant emotional states, the model is intended to offer an easily accessible yet theoretically sound case conceptualisation of how transdiagnostic behaviours function in the movement between and across a range of mental health presentations. With clinical use the primary function, the level of detail displayed is intentionally sparse and the entirety of evidence into the biological, social, psychological and behavioural features of mental health presentations is not incorporated in the framework. It is assumed that the practitioner has a pre-existing understanding of how these factors influence the components of the Infinity Formulation without the need for these to be articulated on the diagram. The model has been employed in clinical practice and is suited to those approaching mental health problems from both a diagnostic and transdiagnostic perspective. Four exemplar formulations are provided to supplement the model presentation.

The model

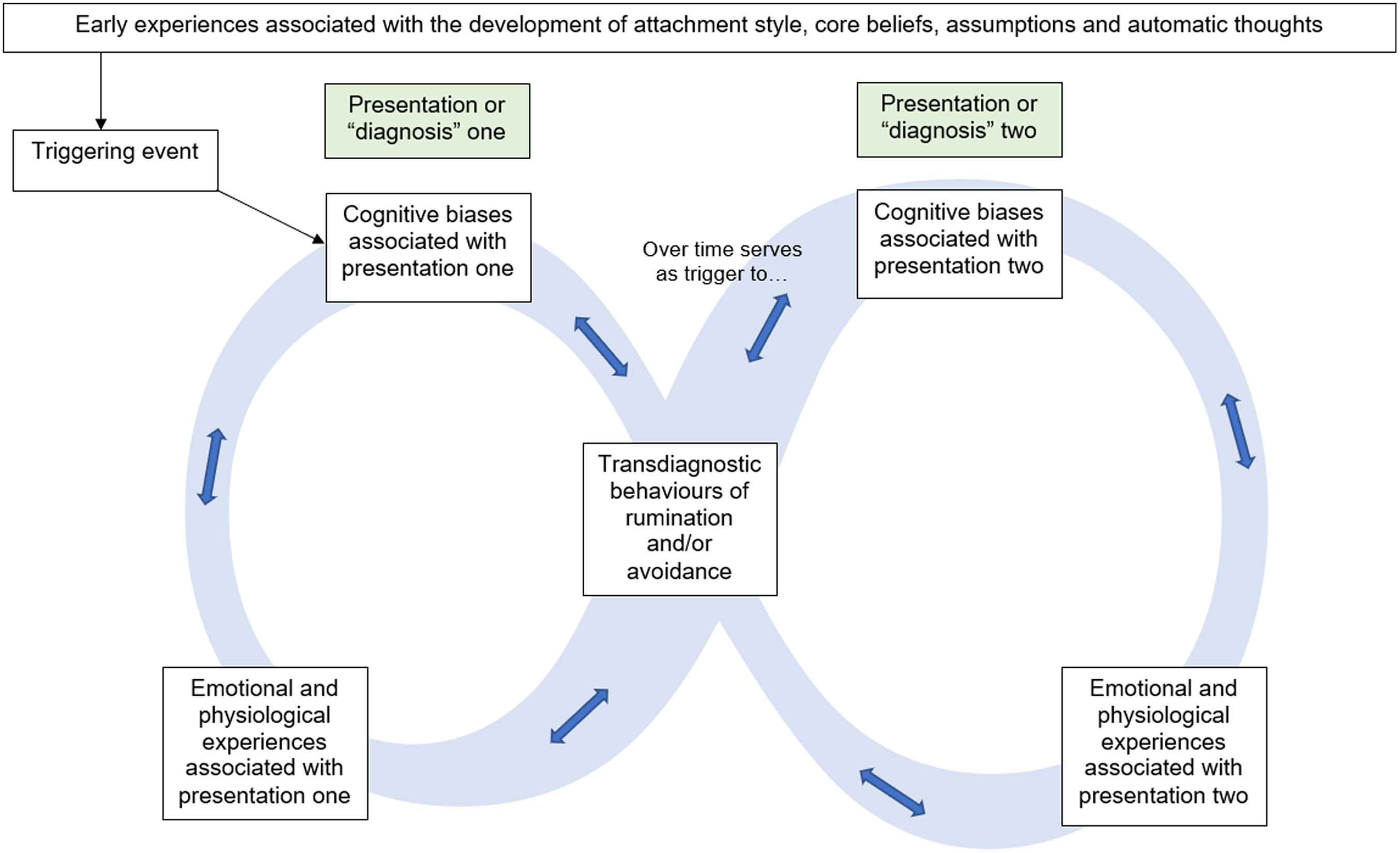

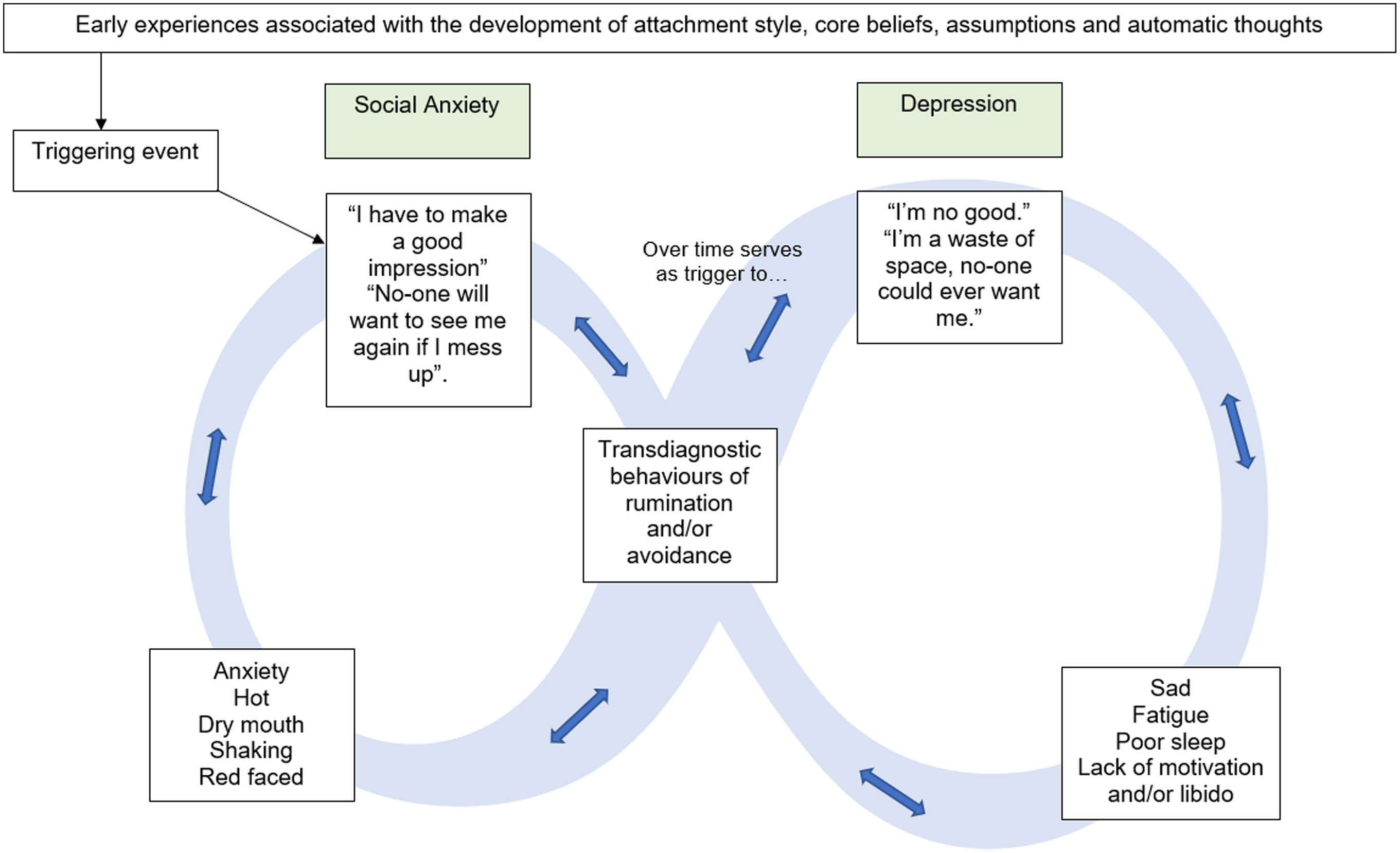

The model posits that the initial onset of mental health difficulties is influenced by early experiences such as attachment style and biopsychosocial experiences during development, and is preceded by a triggering event as per existing cognitive behavioural theories and mental health research evidence (Beck, Reference Beck2011; Kolts, Reference Kolts2016; Mortazavizadeh and Forstmeier, Reference Mortazavizadeh and Forstmeier2018). As can be seen in Fig. 1, this triggers core, intermediate and/or automatic thoughts typically associated with one of the diagnosis-specific presentations (Beck, Reference Beck2011), such as worry in anxiety (Wells, Reference Wells1997), depressive cognitive content in depression (Beck and Perkins, Reference Beck and Perkins2001), over-valuation of eating, weight or shape in eating disorders (Fairburn et al., Reference Fairburn, Cooper and Shafran2003) or threat beliefs in paranoia (Freeman, Reference Freeman2016). This in turn develops into a cycle in which rumination and/or avoidance serve to maintain the initial presentation in any one of the presentations in which one of these behaviours has been implicated [avoidance: psychosis (Tully et al., Reference Tully, Wells and Morrison2017), eating pathology (MacLeod et al., Reference MacLeod, MacLeod, Dondzilo and Bell2019), depression (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Chen and Tseng2019), anxiety disorders (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Smith and Dymond2020); rumination: mood disorders (Wahl et al., Reference Wahl, Ehring, Kley, Lieb, Meyer, Kordon, Heinzel, Mazanec and Schonfeld2019), BPAD (Hanssen et al., Reference Hanssen, Regeer, Schut and Boelen2018), eating disorders (Cowdrey and Park, Reference Cowdrey and Park2012), psychosis (Hartley et al., Reference Hartley, Haddock, e Sa, Emsley and Barrowclough2014)]. The consequences of these behaviours (e.g. limited social engagement, perceived lack of attainment, etc.) then become the subject of rumination which in itself then serves to trigger the cognitive biases associated with the secondary presentation, which then develops in turn to a maintenance of this presentation via the continued use of the transdiagnostic behaviours. The reliance on the use of these strategies can again serve to trigger the original presentation when faced with a similar triggering context to the original presentation. Movement between alternative states can also be triggered by attempts to break a cycle, the consequences of which then become the subject of rumination that over time triggers the cognitive biases of the secondary (or tertiary) presentation. Although each exemplar presented here begins with one presentation, the entry into the interplaying cycles could be initiated by any of the co-morbid presentation states.

Figure 1. The Infinity Formulation Model.

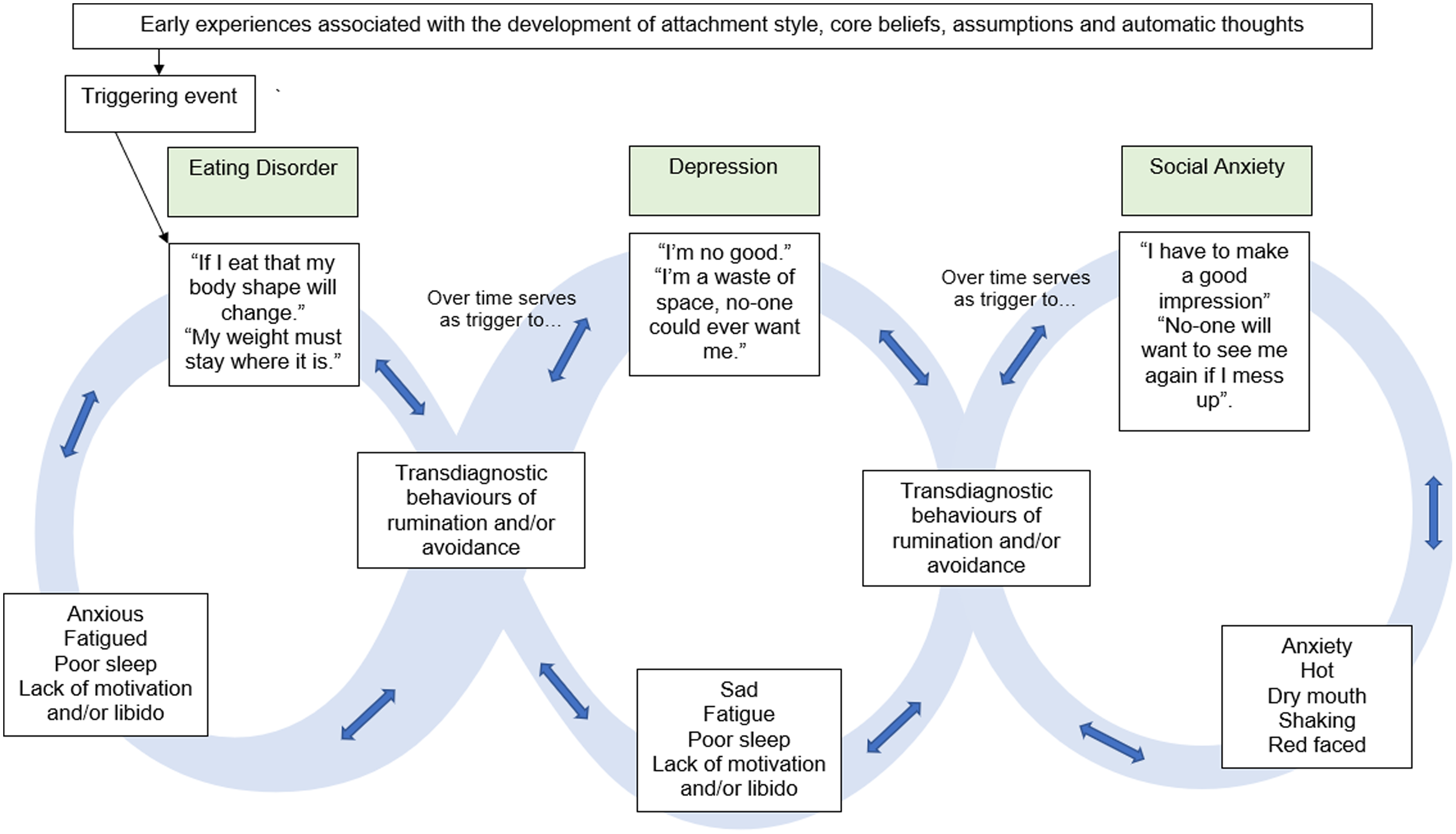

Figure 2 displays a worked example of the interplay between social anxiety and depression. In this example, the initial social anxiety is maintained through avoidance of social situations and ruminative post-event processing (Ishu Ishiyama, Reference Ishu Ishiyama2009; Kocovski et al., Reference Kocovski, Endler, Rector and Flett2005). Over time, the content of this rumination shifts from specific social situations to the lack of valued living and serves to trigger the negative-self beliefs indicated in depression (Abela et al., Reference Abela, Auerbach, Sarin and Lakdawalla2008), a cycle that is further maintained by rumination (Papageorgiou and Wells, Reference Papageorgiou and Wells2001). Behavioural activation is a recommended treatment for depression (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2009), and probably serves to place the person in social contexts as a means of re-engaging with valued living. Thus, as an attempt to break this depressive cycle through behavioural activation, the initial cognitive biases associated with social anxiety are re-triggered. This pattern, in which the transdiagnostic behaviours employed in response to one presentation serve to trigger the cognitive biases associated with the other, co-morbid presentation, may continue indefinitely until the transdiagnostic behaviours are addressed in treatment. As such, over a period of potentially years, the individual may appear to ‘switch between’ multiple primary diagnostic presentations. Figure 3 presents an example of how the model can be extended to explain tripartite presentations above and beyond the mood presentations.

Figure 2. Exemplar of Movement Between States of Mood Disorder using the Infinity Formulation Model.

Figure 3. Exemplar of Movement Between States of Co-Morbid Eating Pathology and Mood Disorders using the Infinity Formulation Model.

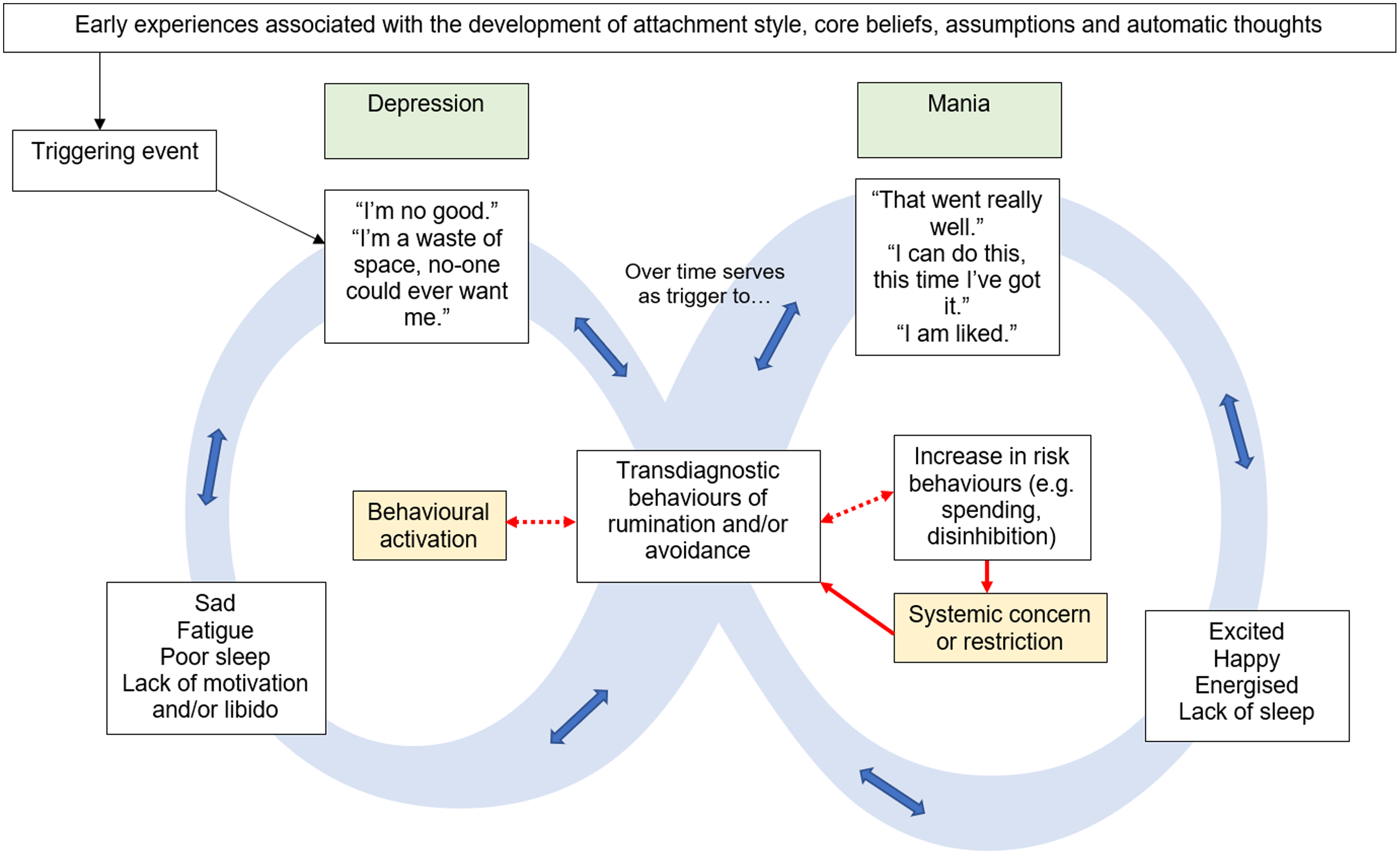

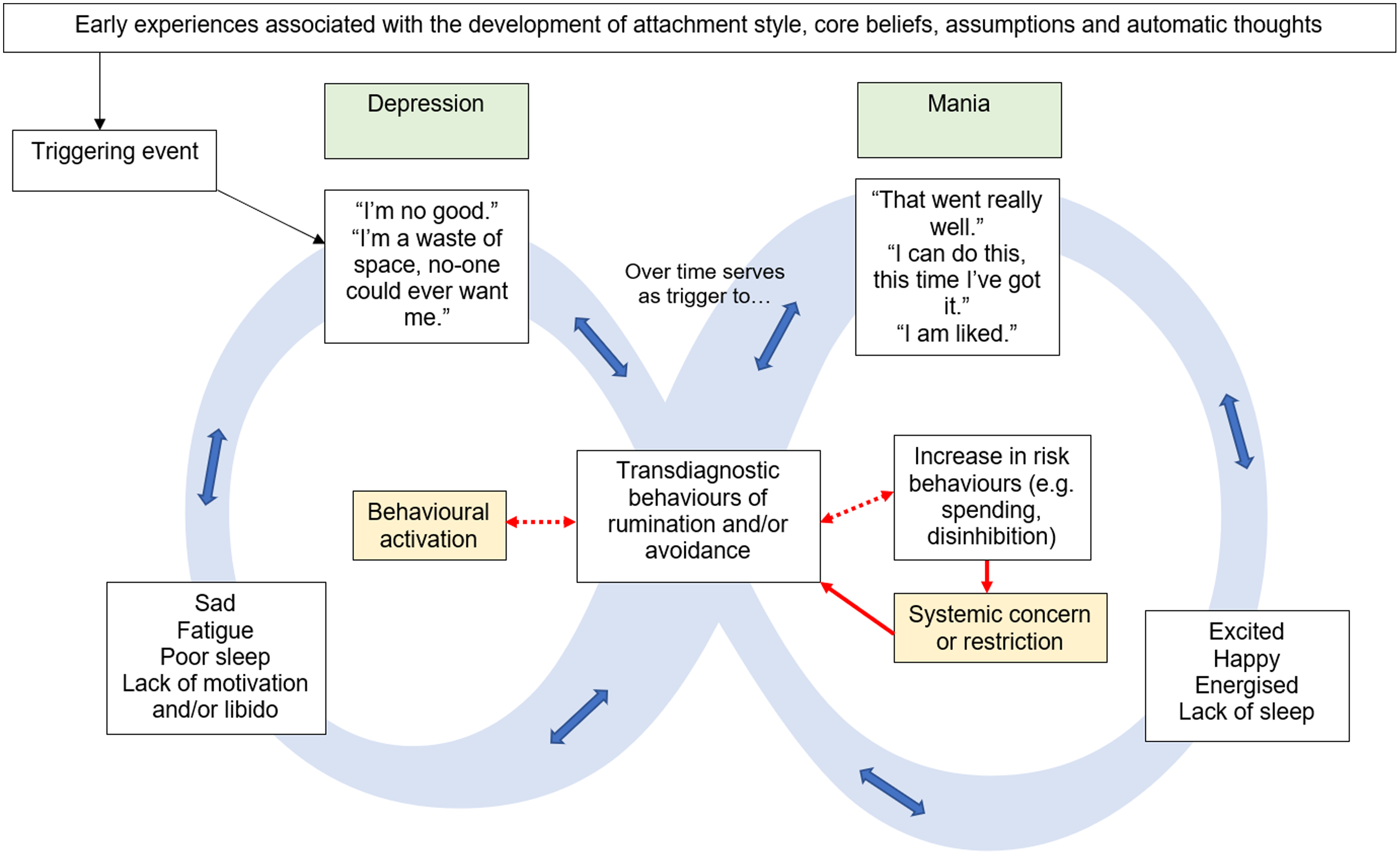

The application of the model to explaining movement between positively and negatively valenced states is displayed in Fig. 4. In a similar manner to previous demonstrations, attempts to break one cycle become the subject of rumination that triggers the alternate state, in this case, the positive outcomes of behavioural activation and the associated emotions become the subject of rumination which initiates the cycle of mania. However, in pleasant states, the motivation to break the cycle is often situated in the system surrounding the person (e.g. family or services’ concern) and often results in restrictive practices such as hospital admission (Karamustafalioğlu et al., Reference Karamustafalioğlu, Reif, Atmaca, Gonzalez, Moreno-Manzanaro, Gonzalez, Medina and Bellomo2014). These attempts to resolve the difficulty, which are hypothesised to ultimately be mechanistic in the triggering of the alternate state, are presented as interacting factors with the transdiagnostic behaviours (shaded in yellow). In this example, increased services input and/or medication may alleviate the manic state; however, should the person then engage in further rumination on the need for this support and/or any risk behaviours engaged in during the elevated state, a further episode of depression would be initiated.

Figure 4. Exemplar of Movement Between Co-Morbid Depressive and Manic States using the Infinity Formulation Model.

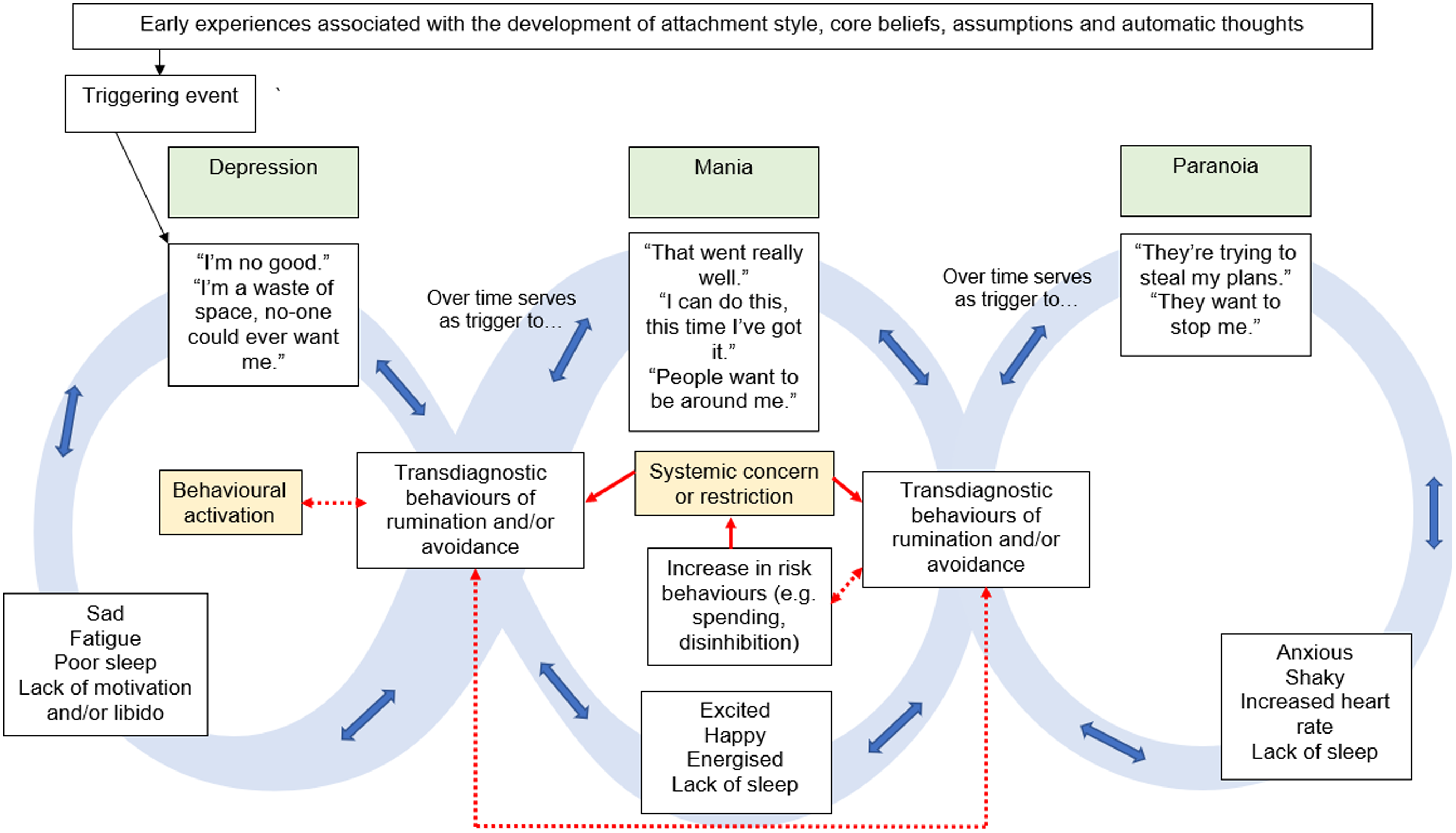

Figure 5 presents a further tripartite presentation in which features of psychosis are seen in combination with features of mood presentations. Mechanistic attempts to break these cycles are presented in yellow, with rumination on these attempts as the hypothesised trigger for the alternate state. The movement between the first and third cycles is depicted by the adjoining of the transdiagnostic behaviours boxes in illustration of how the interpretation of these ruminative and/or avoidant acts in response to paranoia can serve to re-trigger the depression OR mania cycles dependent on the interpretation of the acts. For example, when an individual has moved from depression to mania to paranoia and continues to ruminate, these ruminations may serve to keep the person in a cycle of paranoia and avoidant coping (in combination with the cognitive biases associated with paranoia; Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Dunn, Fowler, Bebbington, Kuipers, Emsley, Jolley and Garety2013). Alternatively, rumination on the paranoid content may lead the person to believe that others’ intention to harm indicates a reinforcement of their positive beliefs about themselves, e.g. ‘They are trying to stop me, which means I must be on to something!’, which may reignite a cycle of mania. On the other hand, in a similar manner to the exemplar in Fig. 2, the paranoid thought content and consequent avoidance may result in rumination over a lack of valued living, thus activating the cycle of depression.

Figure 5. Exemplar of Movement Between Co-Morbid Depressive, Manic and Paranoid States using the Infinity Formulation Model.

Strengths and limitations

The Infinity Formulation provides an evidence-based account of how transdiagnostic behaviours can serve to initiate co-morbidity across a wide range of mental health presentations. The model uniquely offers explanation as to the movement between diagnostic categories including positively and negatively valenced states and beyond an explanation of mood presentations in isolation. The model proposes intervention targets that offer potential to break cycles of co-morbidity in addition to single diagnoses, and additionally uniquely highlights how psychological intervention has the potential to cause harm rather than recovery in some individuals, should the transdiagnostic processes not be attended to in therapy; an important ethical consideration in the delivery of psychological therapies (Jarrett, Reference Jarrett2008). The formulation is simple and accessible to clients and colleagues, and provides a clear and intuitive explanation of repeating cycles for use with both individuals and families in receipt of therapy and multi-disciplinary colleagues involved in their care. To the best of the author’s knowledge, it is the only theoretical formulation that is applicable across diagnostic categories of mood disorders, eating disorders and paranoid states. The model is based on emerging evidence for the role of transdiagnostic processes across a variety of mental health presentations and incorporates these with evidence-based approaches to mental health. However, the precise role of these processes requires further investigation and the model is lacking empirical testing of the specific hypotheses of the role of rumination and avoidance in triggering co-morbid states.

The Infinity Formulation was developed to explain multiple diagnoses and movement between these presentations over time, in keeping with the key function of formulation being to facilitate the understanding of an individual’s presentation (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy, Clarke and Wilson2009). Although the epistemological orientation of the model is one of transdiagnostic processes being the key underlying mechanism of mental health difficulties, the use of diagnostic categories in the model is justified threefold. The reality is that mental health services (see National Health Service, 2019) and practice guidance (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2020) are structured by diagnosis, thus the inclusion of diagnostic categories makes the model directly applicable for use in current clinical contexts. Secondly, formulation is designed not only to guide treatment and validate the service user experience, but also to educate and encourage psychological thinking within multi-disciplinary teams and colleagues who are trained to approach mental health using a diagnostic framework. Clinicians have acknowledged the difficulty in providing a single diagnosis when there appear to be overlapping symptoms (Perkins et al., Reference Perkins, Ridler, Browes, Peryer, Notley and Hackmann2018), and evidence suggests that service users find changing diagnoses distressing (Perkins et al., Reference Perkins, Ridler, Browes, Peryer, Notley and Hackmann2018). The use of diagnostic categories in the model provides a validating explanation as to why these shifts in categorisation may occur, and why transdiagnostic behaviours should be a target for treatment. Finally, the use of diagnostic categories in the model reflects the substantial evidence for some biopsychosocial specificity in mental health research (e.g. cognitive content), making the Infinity Formulation a model based on both clinical expertise and a sound scientific evidence base.

Whilst the simplicity of the presentation can be considered a strength of the model, this should concurrently be held as a possible limitation, as the emphasis on transdiagnostic behaviours is at the expense of crucial diagnosis-specific behaviours such as risky actions in mania (Mind, 2020) and other biopsychosocial and transdiagnostic factors such as emotion regulation. The name ‘Infinity Formulation’ could be seen to potentially provoke a sense of hopelessness; however, this was chosen to reflect the cyclical transition between presenting states rather than duration of the presenting problems, and the hypothesis that targeting transdiagnostic factors could resolve all elements of a co-morbidity is intended to evoke hope rather than hopelessness. Feedback on the service user and staff experience of the model should be sought.

Summary

The Infinity Formulation is a transdiagnostic conceptualisation of co-morbidity in mental health that stipulates rumination and avoidance as core treatment targets. The model draws on existing evidence and presents this in a simplistic way accessible to service users and staff teams. The model requires empirical testing and feedback from service users and staff teams.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge all the service users with whom collaborative working contributed to the inception of this work.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The author is employed at both the University of Southampton and Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust. This content is applicable to both employments and was conceived based on clinical experiences within the NHS role in addition to empirical understanding gained within the University employment. However, this paper was written in the context of the role at the University of Southampton.

Ethical statement

The author has abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. This paper is a theoretical article and thus no ethical approval was required for the project.

Key practice points

(1) A variety of transdiagnostic models are available for use; however, many are limited by the range of presentations they can be applied to, and are inappropriate for clinical use due to the complexity of the information presented.

(2) The Infinity Formulation offers a conceptualisation of co-morbidity that is simple and intuitive yet empirically grounded.

(3) Service user and staff feedback on the model is required.

(4) Empirical investigation of the hypotheses made by the model is required to evaluate the model for use in clinical practice.

Further reading

For further reading on transdiagnostic approaches, see Harvey et al. (2004)

For further information and resources on compassion-focused therapy, see The Compassionate Mind Foundation, available at www.compassionatemind.co.uk

For further reading on acceptance and commitment therapy, see Hayes et al. (2006).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.