We start with a book (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Latin Manuscript 2123.

The book has no title of its own. It now bears the prosaic one assigned it by the library that currently owns it: Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Latin Manuscript 2123 (BNF ms. lat. 2123 for short). The book is not large; closed it measures roughly 6 inches wide by 11 inches high (15.5 × 28 cm), and just over 2 inches (c. 5 cm) thick. Looking up at my office bookshelf, it seems comparable in size to my old Webster’s Collegiate Thesaurus. It is handwritten, and contains a mixed group of texts on a variety of subjects, on which more below. It was copied out at the very beginning of the ninth century in Burgundy, almost certainly by monks at the monastery of Saints Peter and Praiectus in what is now the town of Flavigny-sur-Ozerain.

Flavigny is a very small town (see Figure 1.2). It sits atop a hill in east-central France, on a rocky spur overlooking three streams: the Ozerain, the Recluse, and the Verpant. Today it has a permanent population of around 300. Its only claims to fame are a candy factory that produces the well-known Anis de Flavigny, and the fact that it served as the setting for the 2000 film Chocolat.Footnote 1

At the time our book was written, however, Flavigny was significantly more important. It was located right in the middle of the empire created by the Frankish king and emperor Charlemagne (r. 768–814).

This empire stretched from the borders of Spain, the Atlantic Ocean, the English Channel and the North Sea to the Elbe River, and southwards across the Alps deep into Italy (see Figure 1.3). Its ruler, Charlemagne, was a Carolingian, a member of the family that in the person of Charlemagne’s father Pippin had usurped the title of King of the Franks from his Merovingian predecessors. It was the greatest political entity in Europe since the West Roman Empire had dissolved roughly three centuries before. It was also Rome’s ideological successor; its leaders and propagandists regarded it as the equal of the surviving East Roman or Byzantine Empire centered in Constantinople. Charlemagne staked his personal claim to Rome’s inheritance on Christmas Day of the year 800 by accepting, in St. Peter’s church in Rome and from the hands of Pope Leo III, the crown of Emperor of the Romans.Footnote 2

Figure 1.3 Europe at the death of Charlemagne in 814.

The monastery at Flavigny occupied an important position in the empire’s cultural and political landscape. Ostensibly, monasteries were supposed to be separate from the world. The communities of Christian monks they enclosed were supposed to live lives of isolation and poverty, pursuing both individual and collective closeness to God through tightly scripted routines of communal worship and prayer carried out under the watchful eye of their abbot. In reality, they were anything but isolated. As houses of professional prayers, they naturally attracted the attention and support of laypeople living around them who wanted monks to intercede for them with God. They received gifts, both of goods but more importantly of land, from benefactors who asked in return that the monks pray for them and remember them in prayer after their deaths. They also received gifts of people, in the form of members of local families who became monks themselves in order to burnish their family’s religious bona fides, and in the form of the unfree or semi-free laborers who lived on and worked the land they were given. As a consequence, many monasteries became religious and economic powerhouses. They owned large estates scattered across the empire. They were thoroughly tied into local and regional agricultural economies and networks of trade. The very wealthiest attracted the attention of kings. Kings too wanted to be prayed for, by the very best, and they granted favors in exchange. The favors they granted – royal protection, grants of immunity from royal jurisdiction or exemption from that of their local bishop, freedom from tolls on trade – also brought with them the expectation that kings could draw on “their” monasteries’ economic and military resources (read supplies and manpower) as well as on their prayers and on the political support of their abbots (whom they frequently appointed).Footnote 3

Monasteries also offered the Frankish kings trained administrators and writers, and institutionally organized education. Abbots knew how to manage complex organizations whose often far-flung properties and economic interests required a good deal of record keeping. Monks had to learn to read the religious texts on which their spiritual education depended, to learn the Latin in which they were written, and absorb something of the history necessary to understand them. They therefore needed to acquire and copy out works of history and grammar as well as religious texts, and teachers had to write texts or commentaries explaining them for their students. Monks were by no means the only ones who could read and write. Nevertheless, they, along with the clerics who served the bishops’ churches and who lived in similarly organized and regulated communities, were particularly practiced at it, and had institutions for teaching other people how to do it.Footnote 4 For Charlemagne in particular, who was trying to pull and hold together an empire of enormous scope without the bureaucratic machinery available to the Roman emperors, monasteries offered resources useful for a government and administration that required an unprecedented degree of written communication and record keeping. They also offered him a springboard for his wide-ranging efforts to regularize and improve the standards of Christian worship throughout his empire, an effort that was necessary (from his perspective) both to maintain God’s support for the Franks and to maintain his image as the divinely ordained steward of God’s church and God’s people.Footnote 5

The monastery at Flavigny was one such “royal” monastery.Footnote 6 It was founded at the beginning of the eighth century by a wealthy landowner named Widerad. Widerad himself had family links to the Carolingians; his father had been a sworn follower of Charlemagne’s grandfather Charles Martel. Widerad endowed his new foundation with properties scattered throughout an area of roughly 80 × 130 miles (130 × 210 km) around it.Footnote 7 Within a few decades the foundation was flourishing. It began receiving gifts from other laymen. Among them was Charlemagne’s father Pippin. Sometime between 741 and 751 Pippin gave the monastery a grant of fishing rights on the river Saône enclosed in a pair of precious ivory tablets. In exchange, he asked the monks of Flavigny to pray for him and his descendants.Footnote 8 Pippin included Flavigny’s abbots in his inner circle. Two of them went with him on military campaigns.Footnote 9 Charlemagne kept up the relationship. In 775, he freed the monks of Flavigny from having to pay a variety of tolls.Footnote 10 That same year or the following one, he granted Flavigny perpetual authority over a subsidiary monastery along with a silver reliquary that contained relics of St. James the Apostle and the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. In return, he asked for prayers for himself and his sons.Footnote 11 Sometime around 797, Charlemagne gave the office of abbot at Flavigny to one of the most prominent members of his own inner circle, the Northumbrian scholar Alcuin of York.Footnote 12

Along the way, Flavigny developed an active writing center, or scriptorium, as witnessed by a number of surviving manuscripts written in a characteristic Flavigny script.Footnote 13 Among the products of this scriptorium is our book. I have singled this book out because it opens a door into the world around Flavigny – and into the early Middle Ages as a whole – that most other surviving books or records from the period do not. As the above sketch of the monastery’s history suggests, this world was profoundly different from our own. Religion, specifically Roman Catholic Christianity, was inextricably intertwined with what we would call “secular” society. Priests and bishops, abbots and monks, often came from the same families as lay aristocrats and office holders. Charlemagne and his successors acted as the stewards of the Christian church and Christian people at the same time as they acted as secular rulers, politicians, and military leaders. Each role served the purposes of the others. At the same time, however, religious and secular were not the same. Monks and priests, abbots and bishops, by virtue of the roles that they played in society, were different than peasants, counts, or kings. Written texts distinguish clearly between clerics and laypeople, between those who held church or monastic office and those who did not.

Yet because of the way that our sources from the early Middle Ages have come down to us, we know a great deal more about the former than we do about the latter. Any attempt to explore the lives of any kind of person below the highest elites in this period depends on what we would call archival records: documents or letters that record business transactions or legal matters carried out by people as they went about the business of managing their lives. Put starkly, no one was writing chronicles about the lives of ordinary people, even wealthy ordinary people, unless they became saints or impinged in some other way on the affairs of the great. Most archival records that survive, however, were written and kept by churches and monasteries, or they were issued by kings and kept by churches or monasteries because they somehow affected clerical or monastic interests. The reason for this is quite simple: churches and monasteries as institutions lasted long enough to transmit their archives and libraries to the modern period, where early medieval lay families, even wealthy and powerful families, did not. It is not that laypeople did not use or keep written documents. Far from it. A culture of record keeping and letter writing, inherited from the Romans, which embraced both clerics and laypeople, persisted in western Europe throughout the early Middle Ages.Footnote 14 In the early Carolingian period, however, churches and monasteries, in response both to the upheavals that accompanied the Carolingians’ rise to power and to the Carolingians’ general interest in having everyone keep written track of their rights and resources, began to assemble their documents into organized archives whose contents reflected their institutional interests: records of property transactions and property holdings, disputes over property (which they had won; they had no interest in keeping records of those that they had lost), and grants of rights or privileges from kings. Many of them also copied their documents, or at least some of their documents, into books called cartularies (from the Latin charta = written document or charter). They did so not only for the king’s sake but also for their own, to secure property claims that could be threatened in a rapidly changing landscape of power. Many of these churches and monasteries survived for centuries. Some were destroyed in the wake of the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century, or during the revolutionary ferment of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Nevertheless, they survived long enough that their records and books were either absorbed by newly created national libraries, drawn into personal collections, or copied by people interested in studying the medieval past. Not so for lay families, whose documents were dispersed or discarded as the families themselves died out, or as their interests changed in ways that made older documents no longer important. That early medieval laypeople kept archives at all we know only from hints left, for example, by dossiers of documents concerning lay properties that ended up in a church or monastery archive when the church or monastery acquired the properties, or in records of disputes between a church or monastery and a layperson that describe the layperson producing a document as evidence. As a result of this pattern of source survival, we know about the early medieval laity for the most part only insofar as they interacted with churches or monasteries, or with secular authority figures in contexts that affected churches and monasteries.

Early medieval laypeople did do things, however, that did not affect or even involve churches or monasteries. The problem is how to get at this aspect of their lives. Here is where our book from Flavigny opens a door. This book appears to have a been a compendium of different kinds of texts that would be useful at a monastery. Most of it is devoted to works on theology and church law. It also contains some short texts on weights and measures, calculation, and other things useful for farming and trade.Footnote 15 About two-thirds of the way into it we find our gateway into the lives of the laity: a collection of formulas for documents and letters (see Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 Paris, BNF, ms. lat. 2123, ff. 105v–106r. Flavigny formula collection, prologue and beginning of the table of contents.

These comprise examples or models that were used as templates for actual documents and letters, as sources for language, or as models for teaching students how to draft documents and write letters.Footnote 16 Figure 1.5 shows one example. It represents a document by which one man sells property to another.Footnote 17 The placeholder “N” represents the Latin pronoun ille (or illa in the feminine), which scribes used in place of names to render the text generic:

A Sale

To the magnificent brother N I N. It is agreeable to me to have sold, and thus I have sold, property that I own, situated in the district (pagus) N, in the place called N, with its lands, buildings, tenants (acolabus [sic]), unfree persons (mancipiis), bondservants (servis), freed persons (libertis),Footnote 18 vineyards, meadows, fields cultivated and uncultivated, lakes and streams, moveable and immovable property; I give [this property] entirely and completely, with all of its appurtenances and dependencies and all additions, just as are seen at the present time to be possessed by me, from my right into your power and dominion; whereupon I have accepted a price from you, that is well acceptable to me, in the presence of those, who[se names] have been inserted below, worth so-and-so many shillings (solidi); so that from this day forward, you may have free power to do [with the property] whatever you wish. And if there should be [anyone], I myself or any of my heirs, [or any person, who shall presume to bring any false charge or claim against this sale, let him not win that which he claims, and moreover let him pay so-and-so many shillings to him against whom he raised the quarrel, and let this sale remain firm].

Just under half of the 120 such texts preserved in our book deal with the affairs of clerics and monks. We know this because they explicitly identify the actors involved as clerics or monks. They talk about what clerics and monks did in ways and in language that is entirely consistent with the documents that survive from church and monastery archives. The rest, however, deal with transactions or other matters that only involve members of the laity.Footnote 19 Sometimes they tell us directly that the actors involved were laypeople, with adjectives such as laicus, or by giving them honorific or official titles that belonged only to laypeople. In other cases, however, as in the example above, they simply fail to use any identifying label at all, beyond the term “brother” (frater), which was a polite way to address a fellow Christian.Footnote 20 That these too are “lay” we can surmise from texts covering similar transactions, some of which specify clerical actors and some of which do not. In short, if a given formula text was intended to apply to clergy, it generally says so. If it does not, we can assume that it deals with members of the laity.Footnote 21

Many of these lay formulas represent document types that have not been preserved in church and monastery archives and have thus been lost to us.Footnote 22 Through them we get images of some things that laypeople did, of their activities, concerns, or attitudes. These images are limited. They record only things that laypeople did or were concerned with that produced documents. What they can tell us might be analogous to what we would get if we pulled a modern legal formbook from a lawyer’s bookshelf and derived a picture of our own society from it. Nevertheless, given how few other sources we have from the period, the formulas offer us a great deal. They provide us with a view of the world beyond the monastery walls that we can find nowhere else.

The Laity

When I say that we are going to explore the lives of the laity in Carolingian Europe, I have first to explain what I mean by “laity.”Footnote 23 I use the term to talk about a category of people distinct from those holding an office of some kind within the Christian church, that is, “clergy.” Lay is not, however, a term whose meaning is self-evident or static. It derives from the Greek laos, which originally meant simply “the people” as opposed to their rulers. The word is used in the New Testament in several senses: to refer to simple people, to refer to crowds, or to refer to the people of Israel. In a few cases it denotes Christian communities in opposition to nonbelievers.

At the end of the first century, the term first shows up in something like its later meaning. In a letter attributed to Clement of Rome and addressed to the Christian community in Corinth, the author declares that in sacrifices and services different duties are assigned to the High Priest, to priests, to deacons (Levites), and to members of the laity.Footnote 24 By the turn of the third century, in Christian literature written in Latin, the word laicus is clearly being used to refer to those who did not hold ecclesiastical office: bishops, priests, and deacons together made up a clerical order that was distinct from the laity.

The legalization of Christianity by the Roman emperor Constantine in 313 further reinforced the distinction. Decades of persecution by the Roman authorities had forced clerics and laypeople to think of themselves primarily as common members of threatened Christian communities. With the lid off, different roles played by different members of those communities came to the fore. Constantine himself, and his Christian imperial successors, accentuated the differences dramatically by granting members of the clergy legal privileges, reinforcing their administrative authority within their churches (for example by granting bishops the right to adjudicate disputes among Christians), and drawing clergy into imperial government.

Monks and nuns had no official status within the early church. They were simply Christians who had chosen to lead rigorously Christian lives apart from everyone else. As far as the church as a developing institution was concerned, therefore, they were still laypeople. They were not destined to remain lay, however. Their status as especially holy men and women necessarily created a gulf between them and the broader population of ordinary believers. In Europe, by the time we reach the Carolingian period, monks in their monasteries had become their own order within the clergy: the “regular” clergy (i.e., clergy who followed a regula or rule) as opposed to the “secular” clergy (i.e., who worked in the world, or saeculum). The regular and secular clergy sat on one side of the scale, the laity on the other. The laity defended the realm of the Franks against external enemies, the clergy of both stripes prayed for the salvation of the Christian people. The belief that both priests and monks were clergy persisted throughout the Carolingian period and beyond, when medieval social theorists began to divide their society into three orders: those who prayed, those who fought, and those who worked. Here it was not the religious who were divided, but rather the laity, into those who defended society, namely the warrior aristocracy, and those who supported everyone else: the peasantry. There are hints of this tripartite division of society visible already in the later ninth century, but it only emerges in the sources with any force in the early eleventh.Footnote 25 For the period with which we are concerned, therefore, I will treat the laity as a unity: “lay” means not a priest or any other holder of church office, and not a monk.

Lay society in Carolingian Europe, like that of the church, was hierarchically organized.Footnote 26 At the top were the members of the landholding aristocracy: those that owned property outright and/or held it from the king. The very highest aristocrats owned properties throughout the empire, and they held royal offices, such as count (responsible for justice and military command in defined regions) or royal missi (legates or agents whose missions could vary but that included periodic oversight over counts). Below them were what we might call the middling aristocracy, whose landholdings were smaller. Some of these held local offices such as vicarius (a count’s deputy), centenarius (“hundredman” – a local official), or iudex (judge). They also frequently appear as the “good men” (boni homines) standing alongside the heads of judicial assemblies and rendering judgments. Below them, the ordinary free generally lived under the patronage or protection of someone more powerful. Finally, the unfree were those bound to the land and to their lords by ties of dependence that can be frustratingly difficult to pin down. They included both dependent tenant farmers and household servants whose condition bordered on what we would call slavery. There were laypeople who did not fit into this structure, but they appear in our sources relatively infrequently. Sometimes we read about merchants, and more rarely about Jews, who themselves often appear as merchants, artisans, or physicians.

This lay hierarchy was interwoven with that of the church. Bishops and abbots generally came from aristocratic families and were counted among the great. They headed judicial assemblies alongside counts or served the kings as royal missi. Lay aristocrats were frequently rewarded for their service to kings with the office of abbot of an important monastery – earning them the title “lay abbots” from modern scholars.Footnote 27 Many if not most members of the landholding aristocracy held the use rights to property owned by churches and monasteries, as what were called “benefices” (beneficia, from the Latin for “good deed” – i.e., a “favor” done by the church or monastery to the recipient).Footnote 28 No less important than these material relations were spiritual ones. Monasteries in particular offered members of lay families spiritual support and legitimacy. Individual landholders, or couples, or families donated property in exchange for prayers, and sometimes entry into the books of the dead (necrologies) that guaranteed prayers – and hence their memory – in perpetuity. Holy men or women who founded monasteries on family property or served as abbots or abbesses only strengthened the power of such prayers and provided the family with a closer link to God.

It is the written evidence generated by these constant and close, even symbiotic relationships and interactions between laypeople and members of the clergy that gives us most of the information that we have about the Carolingian laity. Propertied laypeople donated or sold property to churches and monasteries. They exchanged property or worked out benefice arrangements with churches and monasteries (often called “praecarial” or “praestarial” arrangements from the Latin words for “request” and “grant” that appear in the records in which the arrangements are sought and granted).Footnote 29 These transactions generated documents. Through these documents we can see members of the laity connecting themselves to churches and monasteries through property transactions and through the requests for prayers and remembrance that they made on behalf of themselves and their kin. Benefice arrangements could extend for generations through repeated renewals. The people involved enjoyed not only the benefits of continuous prayer, but also the de facto use and inheritance of what they patently regarded as “their” property, and the protection against claims on that property by others that the church or monastery’s de iure ownership provided. By following the history of particular properties through successive charters and observing particular names or naming patterns associated with them, social historians have assembled pictures of kindreds defined by their relationships with individual churches or monasteries, or more extensive kinship networks associated with several. They have exposed the major role played by churches and monasteries in shaping landed families’ sense of their own identity and importance both in this world and the next, and in helping families control and pass on the properties on which their status and power depended.Footnote 30

This last was necessary because property rights were a perennial source of conflict. Factions within kin groups tried to shut their competitors out of inheritances by giving property to churches and monasteries, often with an agreement to get the same property back as a benefice. One of the most common types of dispute recorded in early medieval charters concerns someone suing to stop or overturn a gift of family property to a church or monastery by a relative. Laypeople who felt that their inheritance rights had been violated by a kinsman’s gift sued the church or monastery involved. Churches and monasteries sued those who had seized or refused to relinquish property that someone else had given them. Written records of these disputes ended up in the archives of the church or monastery concerned. These records of conflict tell us a great deal about what happened when people got into disputes either directly with churches or monasteries or with each other when a church or monastery’s property rights were serving one side as a defense. Sometimes cases went before judicial courts, headed at the highest levels by counts, bishops, royal missi, or even the king himself, and at lower levels by vicarii or judges. At other times the parties involved worked out extrajudicial settlements that reflected the balance of power between the parties or pressure from the larger community, sometimes after a formal judgment in a court and with the participation of the judge.Footnote 31

Finally, some laypeople were themselves property: the unfree who worked the land or served in the households of the propertied. Inventories of property written up in records of property transactions, as well as a few surviving estate registers and accounts compiled by monasteries, tell us that these people existed. They and their families appear, however, only as units of economic production, or as property to be transferred along with land. We can, therefore, only learn things about them in aggregate, such as where they lived, what kind of family or household groups they assembled, the way they organized their farmsteads and households, or the sorts of dues that they owed their lords.Footnote 32

Virtually all of this information about the Carolingian laity derives from documents generated by churches and monasteries, which churches and monasteries had an interest in preserving, and which recorded transactions, disputes, or other matters in which churches and monasteries were somehow involved. We could add texts written by clerics and monks that tell stories about laypeople, especially the lives of saints. Early medieval saints’ lives can include among their characters both the great and the not-so-great. They can give us idealized images of the Christian laity both good and bad, but their authors fit these images within religious agendas, that is, making laypeople look saintly or using them as foils to make someone else look saintly.Footnote 33

Nevertheless, laypeople did things and had concerns that did not involve churches and monasteries or their agendas. The question is how to find out about them.Footnote 34 Getting at the activities and thoughts of the great is relatively easy. The most powerful laypeople, namely kings, wrote letters and issued decrees. While most of the royal letters and decrees that survive concern the affairs of religious institutions, not all of them do. However, those that deal with purely lay affairs tell us mostly about the concerns and powers of kings and the concerns and needs of those who had access to kings. Just below the kings, members of the highest elites could be highly educated and become quite learned. They wrote letters, and sometimes histories or other narrative texts that illuminate their doings and those of royal or imperial courts. Prominent among these, for example, are the account of the civil wars among Charlemagne’s grandsons by Nithard, himself a grandson of Charlemagne through a daughter, or the advice manual written by the noblewoman Dhuoda for her son William.Footnote 35

For people lower down the ladder of power and status, however, the task gets much harder. Documents and letters from the early Middle Ages in which the principal actors are lay and in which no clerical actors are involved are scarce. As noted above, some dossiers of lay documents found their way into church or monastic archives because the properties that they deal with were later gifted to or otherwise acquired by the church or monastery. A prime example is the dossier of charters concerning the dealings of one Folcwin, a rather hard-nosed and acquisitive minor official in Rhaetia (in modern-day Switzerland and western Austria), which ended up in the archive of the nearby monastery of St. Gall (which now lies in northern Switzerland near Lake Constance).Footnote 36 Clerical documents or narratives sometimes refer to lay documents that do not survive per se, as for example when a dispute record tells us that a layperson in a property dispute with a monastery produced a document to defend his rights.Footnote 37

These texts or references are sparse and scattered widely across time and space. Because they are apparently so isolated, and because the relevant specialists were generally unaware of what others had, they were for some time either ignored or regarded as the exception that proved the traditional rule, namely that after the Western Roman Empire had dissolved it was clerics and monks who preserved written culture and dominated the production, use, and storage of documents. Members of the laity, so went the narrative, transacted their business orally. They depended on ritual to validate their transactions, and on the memories of witnesses to secure and “store” records of them. The few textual witnesses to lay documents that do survive do not allow us to derive much in the way of useful and especially general conclusions about the lives of the early medieval laity when they were not interacting with clergy or religious institutions. We would have to wait until the twelfth century, when economic growth prompted merchants and other businessmen, driven by the demands of business and trade for accounting, record keeping, and long-distance communication, to adopt writing on a large scale. Only a few specialists in early medieval written culture – most notably Rosamond McKitterick, who famously in the late 1980s worked with the charters from St. Gall – suggested that these traces of a lay documentary culture in fact represented the tip of an iceberg, that is, that they are relics of a once-thriving culture of document use among the laity for which most of the evidence has been lost.Footnote 38

When these relics are put together and studied as a whole rather than in isolation, however, they turn out to be just that: evidence that both laypeople and clergy in Europe, including the lower free and even the unfree, participated in a common documentary culture throughout the early Middle Ages. Students of early medieval documentary culture have recently started looking at the evidence comprehensively and examining the various pieces of evidence in relation to one another. A consensus is building that members of the laity, from all social strata, did in fact continue to use documents from the late Roman period all the way through the early Middle Ages and beyond.Footnote 39 Lay participation in document use did not necessarily involve literacy as it is generally understood today (i.e., the ability to read and write in a given language, in this case Latin). One does not need to be able to read documents, or perhaps more than a few key words, to know what documents were, in what situations they were important, whether or not they needed to be kept and where to store them. Seeing the evidence this way allows us to take it seriously, that is, not as exceptional, but perhaps as representative – as a significant source of information that might tell us something about the larger lay society behind it.

What Are – and Why Are – Formulas?

This brings us back to our starting point. The richest source of evidence for this common documentary culture, and for the lives and concerns of the early medieval laity, are collections of document and letter formulas like that contained in our book from Flavigny.Footnote 40 The Flavigny formula collection contains over one hundred models for documents and letters, or pieces of documents and letters, of varying length. Like the one I gave as an example above, roughly half of these reproduce documents that would only have been of use to laypeople.

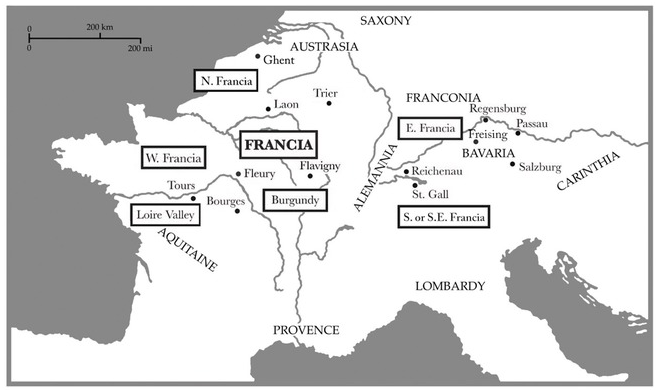

This collection is not unique. Others like it survive in roughly forty manuscripts.Footnote 41 The manuscripts are all Carolingian. They date from the late eighth through the tenth centuries, with the overwhelming majority of them coming from the ninth. Most are west Frankish (i.e., from the regions roughly overlapping with old Roman Gaul that became the core of modern-day France), and especially from the regions on or north of the Loire River. Not all of them are, however. A significant number come from east of the Rhine, namely Alemannia and Bavaria, which encompassed areas that are now in Switzerland, southern Germany, and western Austria (see Figure 1.6).Footnote 42

Figure 1.6 The geographical distribution of extant formula manuscripts. Place names mark manuscripts for which specific origins have been determined or suggested. The rectangles enclosing regional names mark manuscripts that have been assigned to a general region. The big, bold “Francia” in the middle tells us that many of the manuscripts show up in modern library catalogues simply as “Francia, ninth century.”

It is not always possible to say exactly where a given manuscript came from. Handwriting, decoration, or other manuscript characteristics might point to a general region, such as Francia (which covered roughly what is now northern France), and idiosyncrasies in language might do the same. But in many cases it is impossible to say more than that. However, roughly half of the formula manuscripts contain evidence that points quite clearly to churches or monasteries as the places where they were compiled and/or stored, and to or from which they traveled: handwriting and other physical features of a manuscript’s construction, the kinds of texts that the manuscript includes, and/or specific references to particular institutions, places, or people in formula texts or elsewhere in the manuscript. This suggests that many (if not most) of the other formula manuscripts that we cannot anchor in any particular context also originated in a clerical or monastic milieu.Footnote 43 Why were churches and monasteries during the Carolingian period copying and keeping models for lay documents, and what effect do their motives have on the information we can get out of these models about the laity?

Observing when and where the manuscripts were written can help us answer this question. Though we know that some scribes kept and used dossiers of formulas earlier,Footnote 44 from the evidence of the surviving manuscripts it appears that formulas began to be copied and formula collections to be compiled in a big way starting in the eighth century. They continued to be produced throughout the ninth century. The last books containing significant formula collections date from the tenth. While some formula collections have almost certainly been lost,Footnote 45 the sheer number of formula manuscripts from the Carolingian period suggests that it was in this period that churches and monasteries were especially interested in having and keeping them.

This interest coincides with changes in policy at the royal and imperial levels. As noted above, from the middle of the eighth century on successive Carolingian rulers increasingly used writing and written documents as a tool of communication, legislation, and record keeping to help them hold together and manage an ever-growing empire.Footnote 46 At the same time, they patronized monasteries in order to gain access both to their sacred and economic power and resources (e.g., to add an aura of sacred legitimacy to their rule and support followers by encouraging – or pressuring – monasteries to give them benefices), and they drew on monks and clerics both at their courts and in the localities to help them with the business of governing. All of this required reform of religious and administrative practice, as well as education. Our sources reveal a notable interest by Carolingian rulers and their advisors in reforming and standardizing everything from schooling and clerical training to liturgy and religious chants to the scripts used in writing.Footnote 47

At the same time, the character of the scribes writing documents appears to have changed. There is no evidence that this change came in response to a top-down directive, but it does seem from its timing to have followed at least indirectly from the general expansion in the use of writing. In the early eighth century, the people producing documents appear to have included lay scribes as well as local priests, with varying levels of education and skill. From the mid-eighth century on, however, more and more – and eventually all – of the scribes that we know about came from churches and monasteries. In other words, they were trained professionals. They wrote documents for their own institutions and for people who had business with their institutions. They apparently also produced documents that the laity in their areas needed in order to carry out transactions of their own.Footnote 48

The formula manuscripts fit neatly into this context.Footnote 49 They appear just as the Carolingian reforms were getting underway. Moreover, insofar as they can be localized, they stem from areas closest to the centers of Carolingian power, what is now France from the Loire northwards, the Low Countries, and northwestern and west-central Germany, as well as two regions conquered in the course of the eighth century and brought firmly into the Carolingian orbit: Alemannia and Bavaria. The earliest in fact come from the zone on or near the Loire River and northern Burgundy, where Frankish power, and political and religious culture, were strong and overlapped with areas that had been thoroughly Romanized. Here there were still ongoing traditions and memories of Roman legal and documentary practices for the churches, monasteries, and government to build on as they ramped up their use of writing. Farther south, in Aquitaine, Provence, and Italy itself, the stamp of Roman civilization was so strong that a lay notariate persisted with its own practices and traditions of producing documents. There was little need here for churches and monasteries to produce formula collections to guide their scribes and to train their students.Footnote 50 From these beginnings, the practice of creating and maintaining formula collections appears to have spread (if my impression is not a trick of the light caused by the accidents of source survival)Footnote 51 to the east, following the expansion of Carolingian power. Here too, manuscripts containing formulas show up in areas that had formed the northern boundaries of the Western Roman Empire: Flanders and the Rhineland, Alemannia, and Bavaria. None has survived from the Germanic-speaking areas farther north that had never been under direct Roman rule, such as Thuringia or Saxony (which was only firmly brought within the Frankish orbit in the ninth century) and where the habit of using documents had to be implanted from the ground up.Footnote 52

The formula collections appear at the very time when the process of producing documents, and preserving the knowledge of how to produce them and what they were needed for, was becoming the preserve of churches and monasteries and their trained scribes. Apparently, the people who compiled or copied them were reacting to these broader changes. They felt that they needed to have models or sources for language in order to produce the documents needed by the people around them, whether the transactions concerned directly involved their institution or not. They wanted to know how to draft their documents following more or less similar forms and with a more or less similar vocabulary. The formula collections seem to reflect a new interest in keeping copies of forms that would help scribes make their documents more consistent with documentary practice in other parts of the Carolingian Empire, as well as more consistent with each other across time.

The scribes who compiled the formula collections often cast a wide net for their material. Our collection from Flavigny is typical. It draws its models from three sources.Footnote 53 The first is the one major collection of formulas from Frankish Europe that we can be certain predates the Carolingians.Footnote 54 Sometime towards the end of the seventh century and somewhere near Paris (most likely – the date and location are impossible to identify precisely and are still debated), an elderly monk by the name of Marculf put together a quite extensive collection of formulas.Footnote 55 He also, helpfully, wrote a prologue, in which he not only tells us how old he was (70 years or more) but also why he copied out the formulas: at the request of a bishop named Landeric, for the instruction of students learning to write documents:

… I have taken care, according to the simplicity and ignorance of my nature, to include in these pages not only the things which you ordered, but also many others, royal charters as well as private documents. And I know that there will be many, both yourself and other most knowledgeable men and eloquent orators, skilled at rhetoric, who, if they read these things, will rate them as absurd, and of little worth in comparison with their own wisdom, or who will certainly disdain to read them. But I wrote openly and simply, as best I could, not for such men, but to guide the first efforts of youths.Footnote 56

Marculf’s formulas, in their use of language and in their assumptions about the political and legal structure of their universe, undeniably reflect the world of the Merovingian kings, who ruled, or at least reigned, over the Franks and the peoples subject to them from the end of the fifth century through the first half of the eighth. Some, for example, assume a king ruling in tandem with his mayor of the palace, an office which disappeared when the final mayor, the Carolingian Pippin III, deposed the last Merovingian and took the crown of the Franks in his stead.Footnote 57 At the same time, Marculf’s formulas incorporate even older material. Some of the language and descriptions of legal procedure in them go back to late Rome. Several, for example, refer to some characteristic pillars of late Roman civic government, such as a city’s chief magistrate (defensor) and city council (curia).Footnote 58 Despite its older language, however, Marculf’s collection proved to be extremely popular in the Carolingian period. It survives only in Carolingian-era manuscripts. The collection, or pieces of it, or modified versions of texts from it, are in fact among the dominant sources of formulas in the surviving collections. In our Flavigny book, Marculf formulas make up roughly half of the formulas it contains.

The Flavigny collection also draws on two other sources: first, a group of just over thirty formulas from the Loire River city of Tours datable to the middle of the eighth century; although a few of these appear to draw on, or at least share significant language with formulas from Marculf, as a group they are products of the Carolingian period itself.Footnote 59 Second are a few records from Flavigny’s own archives. Notable among the latter are two that tie the collection unequivocally to Flavigny: models for testaments that were derived from the ones by which the monastery’s founder Widerad, in the second decade of the eighth century, endowed his new foundation.Footnote 60

To produce a set of formulas that they thought met their needs, the Flavigny monks selected, wove together, modified, and ordered this material. The result reflects their sense of the possible in the world around them at the time they compiled the collection – that is, it contains images both of their present and possible future needs. These images represent the monks’ view of the possible situations in which they might have to produce documents, or interesting or instructive examples drawn from actual practice, or sources for useful language. And they include situations in which laypeople interacted only with each other. Sometimes this interaction was peaceful:

Agreement between kinsmen

When relatives agree between them concerning the portion justly owed to each out of the inheritance of their relatives without being compelled by a judiciary power, but voluntarily, through constant affection, this is not to be counted as damaging to the property, but rather as being to its advantage, and therefore it is necessary that their [agreement] made between them be recorded in a written document, so that it may not be thwarted by anyone in the future. Thus it was agreed and decided with good will between N and his brother N, through constant affection, that they should divide and share the inheritance of their parents between them, which they did in this manner…Footnote 61

And sometimes it was less so:

To the lord brother N [I] N. Now at the instigation of the adversary [i.e., the devil], you were seen to have killed our brother N, which you should not have done, and because of this you came in danger of your life. But priests and magnificent men intervened, whose names are attached below, and they recalled us in this matter to the concord of peace, such that for this matter, by mutual agreement, you were to give to me so-and-so many shillings …Footnote 62

The Flavigny formula collection went on to have a history of its own. A few decades after it was first compiled, it was copied, perhaps with some additions, into our book. We know that this copy of the collection is not the original, because we have another copy, this one in a manuscript that was written out somewhere in Francia in the middle of the ninth century and is now kept in Copenhagen.Footnote 63 Differences between the two copies (on which more in Chapter 2) indicate that both stemmed from a common exemplar, rather than one from the other. Neither our version nor the Copenhagen version can be the original, though the scholarship has tended to see ours as closer to what it must have looked like (as do I).Footnote 64

When taken as a group, the Carolingian formula collections offer us pictures of society over a lengthy period of time, namely the eighth through the tenth centuries. This period fits into a commonly used historical periodization that is widely regarded, for all of the inevitable blurring at the edges, as a social, political, and cultural unity. But they also offer us more than this. Like the Flavigny collection, the other formula collections also frequently contain older material that reaches back through the Merovingian period as far back as late antiquity. In these embedded layers of time, therefore, we can catch glimpses of societies that preceded those under Carolingian rule and see how the compilers of the Carolingian formula collections processed and made use of the past for their present purposes.

The images we gain from the formulas are necessarily constrained, in their own way as constrained as those we gain from the documents that were kept in church and monastic archives: they reflect only those situations or transactions in which laypeople might be involved that the scribes behind the collection thought were likely to produce documents. Nevertheless, the formulas offer us a different set of images, one that adds a great deal to our understanding of early medieval society, and in particular gives us lively images of laypeople. Despite their generic nature, the formulas even occasionally provide hints of laypeople’s feelings:

To my lord not the sweetest, but rather most offensive and most contemptible husband N, I [the woman] N. As it is not [unknown] how, God having divided us and made us into enemies, we cannot be together, we therefore agreed before good men, that we ought to renounce [i.e., divorce] each other, which thus we have done …Footnote 65

The formulas offer us one other major advantage. The richest tranches of actual archival documents that survive from the Carolingian world come from the eastern parts of the empire, that is, the regions east of the Rhine River, such as Alemannia, Alsace, Bavaria, and the Rhine–Main region, that were on the periphery of the Merovingian kingdoms and that fell under Carolingian domination in the course of the eighth century.Footnote 66 These include, most notably, the ninth-century cartularies from the monasteries at Weissenburg and Fulda and from the cathedral church at Freising, as well as the original charters from the monastery of St. Gall, whose harrowing trip from the early Middle Ages through the religious conflicts of the early modern period to the present was little short of miraculous. In contrast, the documentary survivals from the west are, with rare exceptions (such as the cartulary from the monastery at Redon in eastern Brittany and the earliest surviving originals from the tenth-century monastery at Cluny), sparse.Footnote 67 They consist primarily of handfuls of Carolingian-era documents included in cartularies that were put together much later – from the eleventh century onwards. Flavigny’s own cartulary is a good example. It was begun in the first part of the eleventh century and completed in the early twelfth. It contains some sixty document texts in total. Of these, roughly thirty (depending on how some of them are dated) are from before the year 1000.Footnote 68 Contrast this with the over seven hundred documents from the period 744–848 preserved in the earliest cartulary of Freising in Bavaria alone.Footnote 69 The whys and wherefores of this difference in the source landscape are still debated. Current explanations focus on the strategies chosen by the younger churches and monasteries of the east for organizing and accessing their property and other records in response to the threats and opportunities posed by Carolingian expansion and the “Carolingianization” of the east that followed. St. Gall, as a collection of originals, is an outlier. The story of its archives serves above all to tell us what happened to those originals from other institutions that have disappeared.Footnote 70 Whatever the case, scholars who have wanted to explore regional and local societies in Carolingian Europe in any kind of depth have (with the notable exception of Wendy Davies’ work on Brittany)Footnote 71 been forced to work largely from the east Frankish charter collections. Much of the picture of Carolingian society sketched above in fact is derived from them.

The formulas, in contrast, span the entire Carolingian world. As noted above, many of the richest are concentrated in the west. They therefore give us the chance to explore their compilers’ assumptions about the sorts of things laypeople did in the areas that had been under Frankish domination the longest, and to compare what we learn from them to what we have already learned from the rich documentary survivals from the east – as well as what we can add from the eastern formula collections.

Anchoring the Formulas in the Past

The picture provided by the formulas is not, however, transparent or self-evident. As sources, the formulas come with their own set of problems that for a long time kept them from being fully exploited. Legal and letter formulas are by definition disconnected from a real-life context. They contain in general no names, no dates, and no references to places (though there are a few that preserve some; these will crop up periodically in our discussion). They are also conservative. They may well, and in some cases clearly do, fossilize older ways of doing or recording things. In some cases, this can be extreme. As noted above, a good number of formulas, including but not restricted to those derived from Marculf’s collection, contain language or describe procedures that go back to late Rome. The suspicion lies near at hand that they were preserved not as practical models but rather out of antiquarian interest. The suspicion is only heightened by the fact that they were copied into the surviving manuscripts in a Carolingian period well known for its ruling elite’s interest in drawing on the Roman past both for practical and for ideological purposes.Footnote 72 So when we look at a given formula or group of formulas, are we seeing an image of something that has any connection to something that anyone actually did at the time it was copied down, or just a disembodied anachronism? If the former, then when do the images they present apply?

It is these problems that for a long time kept the formulas mostly – though not entirely – off the radar screen.Footnote 73 In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, legal historians, trained in the scientific, positivist traditions of the period (according to which medieval texts served as sources of facts that could be assembled to reconstruct an objective reality) regarded them as normative sources. That is, they provided prescriptions for how things should be done. A formula like the following told us what was supposed to happen, and therefore what likely happened regularly, when two men got into a dispute over a field (here I have labelled the principals as “A” and “B” rather than “N” to make it easier to follow the action):

Notice, how a man named A came to the judicial assembly (mallus) N before the count’s deputy (vicarius) N and other good men, who were gathered there in their presence, and coming there the man named A was seen to sue another man named B. He laid an accusation against him, in which he said, that he [B] had seized his field in the place named N, in the district N, in the hundred N, in an evil manner and unjustly held it; and that B was present. He was asked by those men, what he wished to say against this, if it was thus true or not; but that B in [their] presence was in no way able to give a response, by which he had lawfully taken possession of that field for himself or ought henceforward to take it; and he in [their] presence made his confession. Then so it was done: it was judged for that B, that he reinvest the abovenamed A with that field through his pledge of 30 shillings according to the law; which he did. Then it was fitting for that A, that he ought then to accept a written notice of this kind of [the decision of the] good men, affirmed by the hand of that deputy; which thus he did.Footnote 74

Formulas like this describing legal procedures, along with law codes and royal legislation, helped legal scholars to construct abstract models of formal legal systems with identifiable and consistent rules. These models, however, better reflected the bureaucratic European monarchies in which these scholars lived or in which they had grown up than the messy and inconsistent nature of early medieval law and legal practice. As positivism fell out of favor in the course of the twentieth century, as medievalists began to approach legal texts as constructions with their own purposes, biases, and agendas and turned their attention to social practice rather than legal abstractions, the formulas attracted less attention. Social historians turned above all to the actual charters that survive from church and monastery archives. They drew precisely on the detailed and contextualized information about people and their property that charters contain and that formulas lack, in order to learn the things about early medieval society both clerical and lay summarized above. Formulas were too distant from actual practice to be of much use.

The apparent distance between the formulas and reality has been exacerbated by the way in which the formulas have been edited and published. The standard edition of the formulas was done by Karl Zeumer in the 1880s for the Monumenta Germaniae Historica (the MGH for short), a nationalist project to publish all of the available sources for medieval German history.Footnote 75 Zeumer approached the formulas in a way typical of his age: he looked through manuscripts that contained the same or related groups of formulas, peeled away differences, textual variants, altered language, scribal mistakes, and so on, to reconstruct as best as possible what he thought were the original form, contents, and origins of the formula collections.Footnote 76 As a result, many if not most of the collections he published are disconnected from the manuscripts in which they actually survive (although if one is willing to put in the effort, one can follow the individual manuscript variants in the footnotes), and hence appear even more disconnected from reality. Sometimes Zeumer’s conclusions and his reconstructed “original” formula collections are perfectly sound, particularly when he is dealing with formulas that appear in only one manuscript. Moreover, Zeumer did the scholarship an enormous service by collecting virtually all of the surviving formula texts in one place and making them readily accessible.Footnote 77 One simply cannot do without Zeumer, and I will be referring repeatedly to his edition throughout this book. But Zeumer’s texts and reconstructed collections are often speculative. They were put together according to Zeumer’s own often idiosyncratic sense of what texts ought to go together and what constituted a “correct” text. They are lifeless: disconnected from their original context, artificially fixed according to Zeumer’s conclusions about the Ur-texts and Ur-collections, and given Latin titles that create for them a fictive reality. For all of their authoritative presentation, therefore, one runs great risks if one treats the formula collections and texts as they appear in the MGH uncritically as something that actually existed, rather than as scholarly creations.Footnote 78

It is in the manuscripts themselves that the formulas and formula collections come alive. They appear not as fixed, but rather in constant flux. We can see scribes selecting their material from both older and contemporary models, and constantly ordering and reordering it into new arrangements in new contexts. Older document texts or formulas were changed, sometimes to make older expressions fit Carolingian realities. Some formulas were plundered for useful phrases, which were then combined from phrases from other formulas to make completely new formulas. Sometimes words or phrases were misunderstood or copied incorrectly, but in many cases such mistakes were identified and carefully corrected. Antique and obsolete language was abandoned or altered but sometimes deliberately kept, both because it lent documents the authority of tradition and because some antique language still had legal meaning. All of this was done by scribes who consciously strove to create collections of model documents and letters that met their current and possible future needs.

It is their efforts, and more particularly the traces they left in the manuscripts, that let us link our disembodied, anonymized texts to a real world. As they stand in the manuscripts, the formula collections mirror the social realities, or possibilities, of the world around the scribes’ institutions as the scribes saw them. In the case of our book from Flavigny, the world is that of northern Burgundy around the year 800. When the other extant formula collections are included, the world expands to encompass the entire Carolingian realm, from its beginnings in the eighth century to its waning in the tenth.

As noted above, just around half of the formula texts in the Flavigny book deal solely with the affairs of the laity. When all of the extant formula collections are taken together, that proportion rises to a narrow majority. Plainly the scribes who put the collections together were interested in knowing how to produce documents that members of the laity around them, of a variety of conditions, might need. The picture of the Carolingian laity we will derive from them is still idiosyncratic and limited. It consists of clerics’ or monks’ views of the documents that members of the laity might need, in those situations that might require documents. Nevertheless, these clerics and monks were very much aware of and connected to the outside world for which they wrote documents.

Opening the Gate

The first part of our journey through the formulas will be devoted to backing up my claims that despite all of their difficulties as a source, we can in fact use the formulas to illuminate the lives of the Carolingian laity. Starting with our Flavigny book and comparing it to others, I will focus on the manuscripts, the form in which the formulas appear in them, and the language in which they were written. These were not collections of old texts put together out of antiquarian interest. Their compilers drew material from the past and assembled it in their presents into collections meant to meet the imagined needs of their possible futures. They intended their collections to be used, whether as models for imitation, sources of language, examples for students, or collections of interesting case studies – or all of the above – and for the documents produced from them to be understood, at least at a basic level. I will be treating the formulas therefore as documents of practice, but in a different way than historians have treated the surviving charters and letters. Unlike actual charters, whose context is generally derived from the specific information they contain, the formulas’ contexts emerge from the ways that they were assembled, selected, altered, and so on, and copied into the manuscripts in which they actually survive. Anchoring the formulas in reality this way allows us then to explore lay society as they envision it with reasonable confidence that we are at least looking at images of the possible as understood by their compilers.

The second part forms the heart of the project. Here we will explore lay society in the Carolingian period as the formulas project it. At the center again will be the formulas in the Flavigny collection. The way that this manuscript combines formulas from several traditions into a single collection both allows us to explore lay society in the area around Flavigny as the compilers of the Flavigny collection imagined it and to link what we find to formulas from other parts of the Carolingian world. I will move thematically, first covering the evidence in the formulas that laypeople actually used the kinds of documents that they represent, then moving through the following subjects: laypeople and their property; lay families and kinship; laypeople in conflict; the vertical relationships between those people who had more power and those who had less, such as lordship and patronage, which structured lay society; ideas both legal and practical among the laity about freedom and unfreedom. These themes largely reflect the preoccupations and interests of the formula collections themselves, that is, the elements of lay life that the compilers of the collections thought required (or were likely to require) documents. There will be overlaps. Many formulas contain information that illuminates several aspects of lay society, and some formula texts as a result will show up in more than one chapter. I freely admit that other readers will almost certainly see things in the formulas that I have missed and that deserve attention. But that is part of the point. As a source on Carolingian social history and on the Carolingian laity in particular, the formulas are virtually inexhaustible. I hope here simply to open the door.

A Readers’ Guide

To perhaps state the obvious, the formulas we will be exploring are written in Latin, the language inherited from Rome that remained the vehicle of written communication, legislation, and record keeping not only for the western church but also among the laity. Since I would like this book to be read by people who do not read Latin as well as by those who do, I will continue to do what I have done in this chapter, namely provide English translations of the formula texts that are relevant to whatever it is I am talking about. The generic Latin pronouns that stand in for the names of people and places I will for the most part represent with the letter N (as indeed some formula collections do, notably the largest one from St. Gall – N standing for the Latin nomen, or “name”).Footnote 79 Only in cases where sticking strictly to “N” would make it hard for readers to follow who is doing what will I resort to giving the individual actors their own letters, that is, “A,” “B,” “C,” and so on.

Occasionally I will italicize words or phrases within a translation. Sometimes, to make it clear what Latin word(s) I am translating, or to give readers a chance to question my translations, I will put the Latin original in italics in parentheses. However, I will also use italics in the English translations themselves to flag points where a scribe inserted language into a formula text that does not, strictly speaking, belong to the text itself. Our scribes quite often set up their formulas to apply to a range of possible actors or scenarios. For example, a transaction could be carried out by a man acting alone, or by a man and his wife. It could involve landed property or an unfree person. It could benefit the man (or the couple’s) son, or daughter, or grandchildren. One man could be charged with killing another man’s brother, or son, or nephew. Whenever a scribe included options such as these, and inserted an “or” in between them, I will place the “or” in italics, to make it clear that we are being presented with a range of possibilities. In addition, some scribes, to save space, abbreviated their formulas by subsuming common and apparently well-understood phrases within abbreviations such as “and the rest” (et reliqua) or “and so forth” (et cetera). These abbreviations too I will translate and italicize. Finally, a number of scribes included in their formulas instructions for how to use them or added comments about them. Whenever such a scribal instruction or comment appears in one of the formulas I have chosen to present, I will likewise translate it and put it in italics.

To avoid boring readers with complete translations of texts that tend to reproduce the same kind of language over and over, I will often translate only the parts of a given formula that I think are relevant. Where I have left off a beginning or an ending, or text in the middle, I will place ellipses. If a beginning, ending, or part in the middle was missing in the original, I will say so in brackets. I will also use brackets to insert words that do not appear in the original Latin, but that need supplying in order to have the translation make sense in English.

Finally, some notes about my texts and translations. First, given the length of some of the formulas, I have not provided the complete Latin texts in the notes. I have instead referred to the manuscripts and to the relevant pages of Zeumer’s MGH edition of the formulas (or others, when relevant), where the Latin originals can be found. Second, Latin syntax, especially early medieval Latin syntax, and very especially early medieval legal or documentary Latin syntax, can be quite different from that of modern English. I have therefore been forced every once in a while to depart from a literal translation of the formula texts, both in order to make the translation accurately reflect the sense of the original and to make it comprehensible to readers. When the departure is significant enough to require explanation, I have put the Latin original in the notes. Third, I have occasionally borrowed from, or adapted to my preferences, English translations done by other people – especially the excellent translations of the Marculf and Angers formulas published in 2008 by Alice Rio. I acknowledge in the notes (and with profound thanks here) my debts to these brave translators of what are often difficult and obscure texts.

Finally, as I have noted repeatedly in this chapter, at the heart of this project lies one particular manuscript: our book from Flavigny. This book combines formulas from different sources, two of which (the formulas of Marculf and the formulas from Tours) also survive in other manuscripts. For those in my audience who may be reading with the MGH edition to hand, every time I translate a formula from our manuscript, the translation follows the text as it stands in this manuscript. Since no two versions of these hand-copied texts are exactly alike, and can in fact differ from each other quite substantially (see Chapter 2), my translations will therefore occasionally depart from the Latin texts of the corresponding Marculf or Tours formulas as they are published in the MGH, as well as, in the case of Marculf, from Rio’s translations. When I translate formulas from other manuscripts that similarly survive in several copies, I will say which manuscript I am using as my basis in the notes.