Non-technical Summary

The fossil record of the Pacific Northwest records millions of years of changing climate and evolving organisms, shedding light not only on life of the past, but also giving us the tools to better predict how future environmental change might play out. A site near Pendleton, Oregon is especially important to understanding ancient ecosystems because it preserves a complete community of vertebrates, from bats and shrews to rhinos and saber-toothed cats. In 2017 and 2021, we returned to this site to collect new fossils. We also visited museum collections that contain fossils from the site to open as clear a window as possible into this 5–6 million year old world. We identified many species new to the site, many of which are also new to the Northwest. These include a bone-crushing dog; camels, both giant and llama-like; an extinct animal that looked like a deer, but that has no modern relatives; and at least two types of ancient horse. We also compiled a complete, up-to-date list of all the mammals ever found at the site. Besides giving us a better idea of what lived in the Pendleton area in the Miocene Epoch, this work will serve as a jumping-off point for later studies focused on how these organisms behaved, functioned, and interacted with each other and with their environments.

Introduction

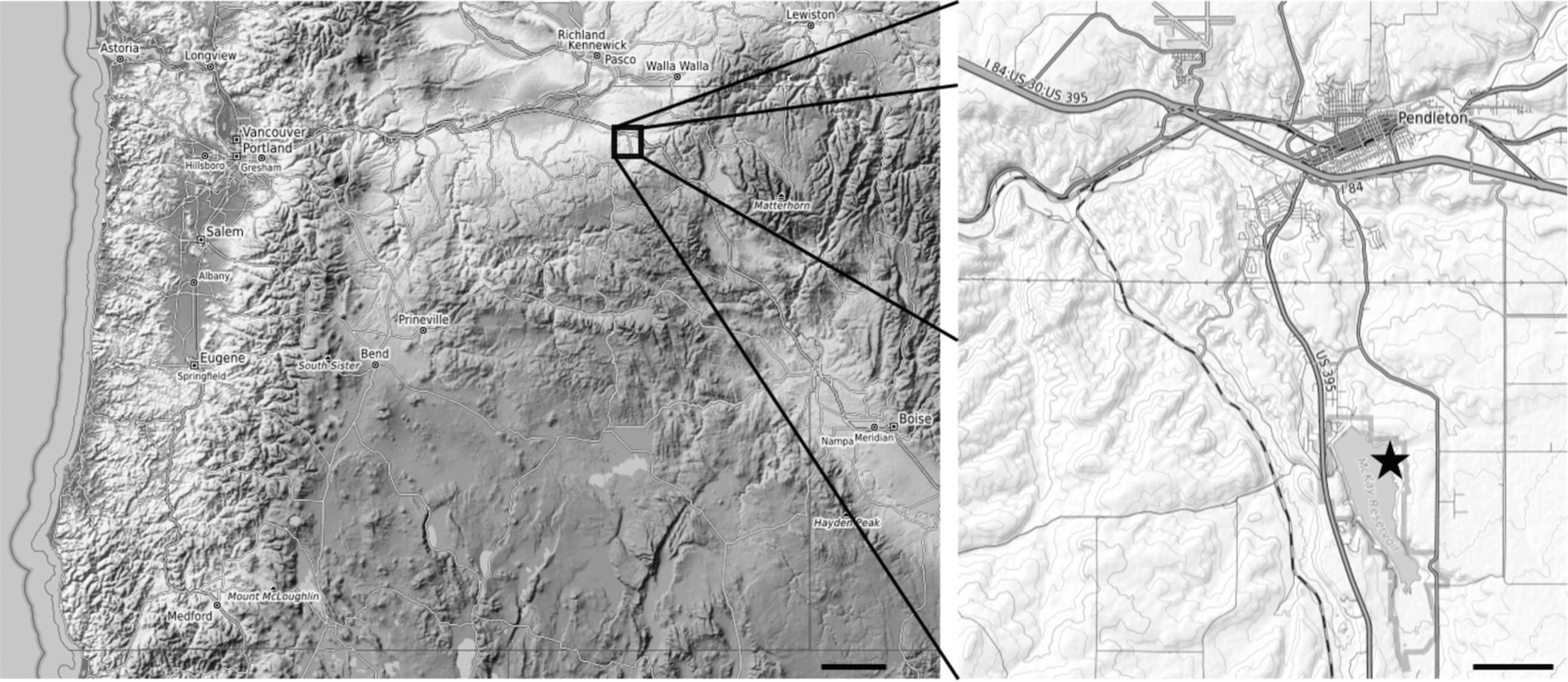

The Hemphillian North American Land Mammal Age (NALMA; Miocene, 9–4.9 Ma; Bell et al., Reference Bell, Lundelius, Barnosky, Graham, Lindsay, Ruez, Semken, Webb, Zakrewski and Woodburne2004; Tedford et al., Reference Tedford, Albright, Barnosky, Ferrusquia-Villafranca, Hunt and Woodburne2004; May et al., Reference May, Sarna-Wojcicki, Lindsay, Woodburne, Opdyke, Wan, Wahl and Olson2014) spans an interval of profound ecological change, encompassing climatic cooling, the continued spread of grasslands, and the migration of new taxa from Eurasia and South America (Woodburne, Reference Woodburne and Woodburne2004). The McKay Reservoir locality near Pendleton, Oregon (Fig. 1) offers a rare opportunity to study the effects of large-scale change on an ecosystem scale. The site preserves an important Hemphillian-aged vertebrate fauna (Shotwell, Reference Shotwell1956). It is especially remarkable for its diversity of small vertebrates, including birds (Brodkorb, Reference Brodkorb1958), rodents (Martin, Reference Martin2008), turtles, eulipotyphlans, bats, and lagomorphs (Shotwell, Reference Shotwell1956). Larger mammal fossils are also common at the site. The rhinocerotid Teleoceras Hatcher, Reference Hatcher1894 is particularly abundant (Shotwell, Reference Shotwell1956) and the site has also yielded a diversity of carnivoran fossils, including borophagine (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Tedford and Taylor1999) and canine canids (Tedford et al., Reference Tedford, Wang and Taylor2009) and the giant felid Machairodus lahayishupup Orcutt and Calede, Reference Orcutt and Calede2021 (Orcutt and Calede, Reference Orcutt and Calede2021). The exceptional completeness of the fossil record from McKay Reservoir has made it a major focus of paleobiological research. Shotwell (Reference Shotwell1955a) argued that the taphonomy of the McKay Reservoir fossils indicated a pond-bank environment and built on this by including the McKay Reservoir fauna in a pioneering analysis of landscape paleoecology in the Columbia River Basin (Shotwell, Reference Shotwell1958). The site's continuing importance as a paleobiological study system is underscored by the many subsequent studies incorporating McKay Reservoir fossils to address questions regarding mammalian body-size evolution (Orcutt and Hopkins, Reference Orcutt and Hopkins2013, Reference Orcutt and Hopkins2016), morphological variation in mylagaulid rodents (Calede and Hopkins, Reference Calede and Hopkins2012), the biogeography of arvicoline rodents (Martin, Reference Martin2010), the origin of sigmodontine rodents (Ronez et al., Reference Ronez, Martin, Kelly, Barbiere and Pardiñas2021), rhinocerotid paleopathology (Stilson et al., Reference Stilson, Hopkins and Davis2016), and felid functional morphology and systematics (Orcutt and Calede, Reference Orcutt and Calede2021). As extensively and intensely as it has been studied, the McKay Reservoir faunal list continues to grow, due to taxonomic revisions, to previously described taxa, and to new collections made by Gonzaga University field crews in 2017 and 2021. Here, we present the occurrence of several mammalian taxa not previously identified from McKay Reservoir and revisit prior identifications by Shotwell (Reference Shotwell1956), providing a more complete assessment of diversity in this paleoecosystem and laying the foundation for future paleobiological analyses.

Figure 1. Maps showing location of McKay Reservoir within Oregon (left) and of fossil bearing outcrops along reservoir shoreline (right). Scale bars = 50 km (left); 2 km (right). star, site of fossil bearing outcrops.

Geologic setting

The McKay Formation, from which the specimens described here were collected, is a component of the late Miocene Dalles Group, previously referred to as the ‘Shutler Formation’ (Farooqui et al., Reference Farooqui, Beaulieu, Bunker, Stensland and Thoms1981). The fossil-bearing units of the formation outcrop only along a 0.3 km section of shoreline on a peninsula on the northeast shore of McKay Reservoir (Fig. 1). The sediments at the locality range from siltstone to conglomerate (Farooqui et al., Reference Farooqui, Beaulieu, Bunker, Stensland and Thoms1981), with most fossils preserved in the siltstone and sandstone units (Shotwell, Reference Shotwell1956). Most McKay Reservoir fossils are found in float along the lake shore, exposed by wave erosion during periods of high water, making it impossible to assign these specimens to a particular stratigraphic unit. As first noted by Shotwell (Reference Shotwell1956), McKay Reservoir fossils show minimal evidence of abrasion or any other extensive alteration prior to burial. Although some specimens show signs of weathering and breakage, these appear fresh and are likely the result of changing water levels in the reservoir and a strongly seasonal modern climate. However, a detailed taphonomic analysis of the site has not yet been undertaken.

The fossils uncovered from McKay Reservoir are characteristic of the early late Hemphillian (Hh3) NALMA and allow a biochronologic age estimate of 6.7–5.9 Ma (Tedford et al., Reference Tedford, Albright, Barnosky, Ferrusquia-Villafranca, Hunt and Woodburne2004). Two tephras are interbedded within the fossiliferous layers of the McKay Formation at McKay Reservoir with 40Ar/39Ar dates of 5.95 ± 0.30 Ma and 5.51 ± 1.22 Ma (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Hargrave and Ball2018). Most fossil sites are between the two tephras but there are rare fossil specimens below the lower ash including possible material of Megatylopus Matthew and Cook, Reference Matthew and Cook1909. There are abundant fossils in the unit immediately above the upper tephra (Shotwell, Reference Shotwell1956; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Hargrave and Ball2018). However, all of these specimens remain consistent with the Hh3 NALMA (Tedford et al., Reference Tedford, Albright, Barnosky, Ferrusquia-Villafranca, Hunt and Woodburne2004) and therefore are unlikely to significantly pre- or postdate the tephras.

Materials and methods

Many specimens were collected at McKay Reservoir (University of Oregon Locality UO 2222) by field crews from Gonzaga University in July of 2017 and 2021. The reservoir is part of McKay Creek National Wildlife Refuge and collection was carried out under Permits for Paleontological Investigations issued by the US Bureau of Reclamation (CCAO:U17-001 and CCAO:U21-004) and Special Use Permits issued by the US Fish and Wildlife Service (FF01RMCC00-17-021 and FF01RMCC00-21-005). Measurements of specimens were made to the nearest tenth of a millimeter using Mitutoyo Digimatic calipers with an accuracy of ± 0.02 mm. In the text and tables, upper dentition is indicated by uppercase letters, lower dentition indicated by lowercase letters.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

Specimens from McKay Reservoir are reposited in the following collections: the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology (SDSM; SDSM V for locality numbers), the University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP, UCMP V for locality numbers), the University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History (UOMNH F, UO for locality numbers) and the University of Washington Burke Museum (UWBM VP, UWBM C for locality numbers). Another cited repository is American Museum of Natural History, New York (AMNH).

Systematic paleontology

Order Carnivora Bowdich, Reference Bowdich1821

Family Canidae Fischer De Waldheim, Reference Fischer de Waldheim1817

Subfamily Borophaginae Simpson, Reference Simpson1945

Tribe Borophagini Wang et al., Reference Wang, Tedford and Taylor1999

Subtribe Borophagina Wang et al., Reference Wang, Tedford and Taylor1999

Genus Borophagus Cope, Reference Cope1892

Type species

Borophagus diversidens Cope, Reference Cope1892 from the Blancan Blanco Formation at Mt. Blanco, Texas, USA, by original designation.

Borophagus secundus (Matthew and Cook, Reference Matthew and Cook1909)

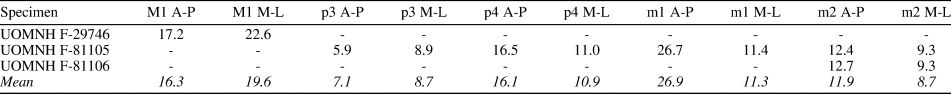

Figure 2; Table 1

Holotype

Left ramus (AMNH 13831) from the Hemphillian Johnson Member of the Snake Creek Formation at Sioux County, Nebraska, USA.

Figure 2. Borophagus secundus (Matthew and Cook, Reference Matthew and Cook1909) from McKay Reservoir: (1, 2) right dentary (UOMNH F-81105): (1) occlusal view; (2) lateral view; (3) right lower m2 (UOMNH F-81106); (4) left upper M1 in occlusal view (UOMNH F-29746). Scale bar = 1 cm.

Table 1. Measurements of Borophagus secundus (Matthew and Cook, Reference Matthew and Cook1909) from McKay Reservoir. Anteroposterior (A-P) and mediolateral (M-L) measurements (in mm) shown for upper molars (M), lower premolars (p), and lower molars (m). Mean values for Borophagus secundus dental measurements shown in italics (n = 250; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Tedford and Taylor1999). -, not available.

Description

Large size of teeth and presence of small m2 on UOMNH F-81105 and F-81106 suggest that specimens can be attributed to a borophagine canid (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Tedford and Taylor1999). Weakly developed mandibular boss below symphysis and smaller width of m1 trigonid than of p4 are all characteristic of Borophagus as opposed to Epicyon Leidy, Reference Leidy1858. Specimens have several traits characteristic of Borophagus secundus: tip of the main cusp of the p4 is higher than the m1 paraconid. P4 is very strongly posteriorly sloped, compressing posterior accessory cusplet; p4 has a triangular shape in occlusal view and overhangs labial face of ramus; roots of p4 are visible on labial side as it is significantly laterally displaced; m1 talonid is reduced; m2 is relatively unreduced; and m2 metaconid is higher than protoconid. Size of UOMNH F-29746 and presence of strong labial cingulum on M1 are consistent with Borophagus secundus (Table 1).

Referred material

UOMNH F-81105, right dentary with p3–m2; UOMNH F-81106, right lower m2; UOMNH F-29746, left upper M1; all specimens from McKay Reservoir (UO 2222).

Remarks

Although Borophagus secundus has been reported from many Hemphillian-aged sites elsewhere in North America, these specimens represent a northward range extension (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Tedford and Taylor1999). Although some fossils described by Shotwell (Reference Shotwell1963) from the Drewsey Formation of southeaster Oregon could be attributable to Borophagus secundus, UOMNH F-81105 marks the first definitive occurrence of the species in Oregon and in the Pacific Northwest more broadly.

Order Artiodactyla Owen, Reference Owen1848

Family Camelidae Gray, Reference Gray1821

Tribe Camelini Webb, Reference Webb1965

Genus Megatylopus Matthew and Cook, Reference Matthew and Cook1909

Type species

Megatylopus gigas Matthew and Cook, Reference Matthew and Cook1909 from the Snake Creek Formation at Nebraska, USA, by original designation.

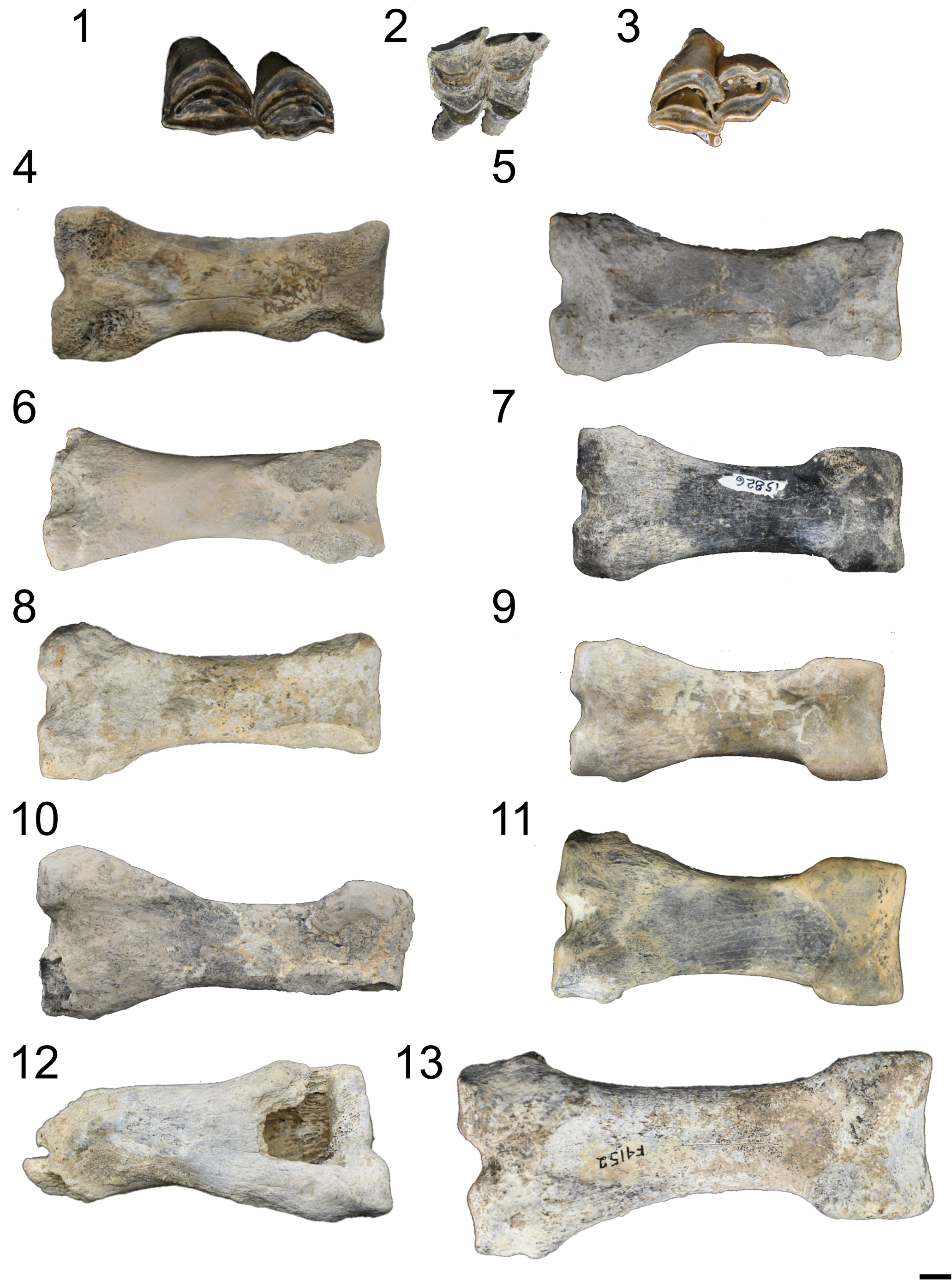

Description

Large size (Table 2), relatively low crowns, and lack of cement in fossettes of cheek teeth are characteristic of Megatylopus (Jiménez-Hidalgo and Carranza-Castañeda, Reference Jiménez-Hidalgo and Carranza-Castañeda2010). Phalanges are intermediate in robusticity (Table 2), as in Titanotylopus Barbour and Schultz, Reference Barbour and Schultz1934, Megatylopus, and Camelops Leidy, Reference Leidy1854; are consistent in size with Megatylopus and Camelops; and have a W-shaped suspensory ligament scar, as in Titanotylopus and Megatylopus (Voorhies and Corner, Reference Voorhies and Corner1986).

Figure 3. Megatylopus sp. indet. from McKay Reservoir: (1) left m1 or m2 in occlusal view (UWBM 61682); (2) left M1 or M2 in occlusal view (UOMNH F-81109); (3) right M3 (SDSM 51260); (4–13) proximal phalanges in plantar view: (4) UOMNH F-81111; (5) UOMNH F-81110; (6) UCMP 113536; (7) SDSM 15826; (8) UOMNH F-4153; (9) SDSM 28013; (10) SDSM 12812; (11) UMNH F-3843; (12) UOMNH F-71508; (13) UOMNH F-4152. Scale bar = 1 cm.

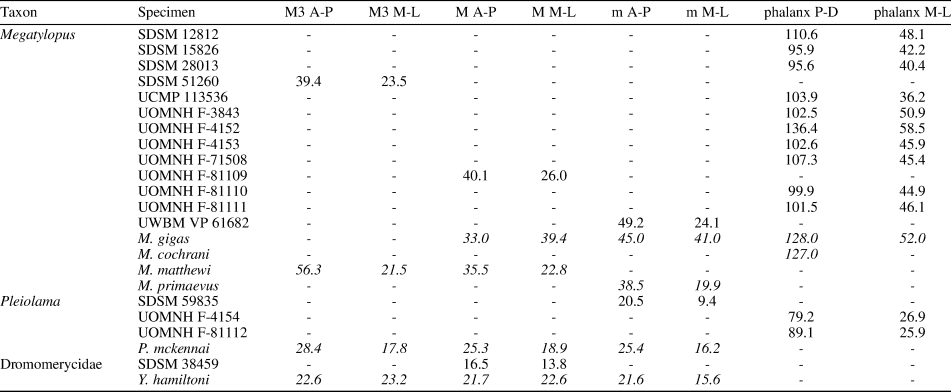

Table 2. Measurements of artiodactyls from McKay Reservoir. Mediolateral (M-L) measurements (in mm) shown for upper molars (M), lower molars (m), and proximal phalanges. Length measured anteroposteriorly (A-P) for molars and proximodistally (P-D) for phalanges. Mediolateral measurements of phalanges made at the proximal end of the bone. Mean values for the upper molars from the species description of multiple camelid and dromomerycid species shown in italics, including Megatylopus gigas Matthew and Cook, Reference Matthew and Cook1909 (n = 1), Megatylopus cochrani (Hibbard and Riggs, Reference Hibbard and Riggs1949) (n = 1), Megatylopus matthewi Webb, Reference Webb1965 (n = 2), Megatylopus primaevus Patton, Reference Patton1969 (n = 1), Pleiolama mckennai Webb and Meachen, Reference Webb and Meachen2004 (n = 5), and Yumaceras hamiltoni (Webb, Reference Webb1983) (n = 5 M3, 10 M, 16 m).

Referred material

SDSM 12812, proximal phalanx; SDSM 15826, proximal phalanx; SDSM 28013, proximal phalanx; SDSM 51260, right M3; UCMP 113536, proximal phalanx; UOMNH F-3843, proximal phalanx; UOMNH F-4152, proximal phalanx; UOMNH F-4153, proximal phalanx; UOMNH F-71508, proximal phalanx; UOMNH F-81109, left M1 or M2; UOMNH F-81110, proximal phalanx; UOMNH F-81111, proximal phalanx; UWBM VP 61682, left m1 or m2; all specimens from McKay Reservoir (SDSM V802, UCMP V74163, UO 2222, UWBM C0128).

Remarks

Shotwell (Reference Shotwell1956) indicated the presence of a large and small camelid at McKay Reservoir but did not identify these camelids to genus. The larger material described above is referable to Megatylopus, the first definitive identification of this genus at McKay Reservoir, although Martin et al. (Reference Martin2010) indicated the presence of the genus at the site without assigning specific specimens to it. Many of the specimens are smaller than those found at sites elsewhere in North America (Table 2; Voorhies and Corner, Reference Voorhies and Corner1986; Jiménez-Hidalgo and Carranza-Castañeda, Reference Jiménez-Hidalgo and Carranza-Castañeda2010) although UOMNH F-4152 is extremely large, indicating a wide range of body sizes (Table 2). Whether this is the result of sexual dimorphism, the presence of multiple species, or simply normal variation within Megatylopus cannot be ascertained based on the sample size currently available.

Tribe Lamini Webb, Reference Webb1965

Genus Pleiolama Webb and Meachen, Reference Webb and Meachen2004

Type species

Pleiolama mckennai Webb and Meachen, Reference Webb and Meachen2004 from the Clarendonian Merritt Dam Member of the Ash Hollow Formation at Kat Quarry, Nebraska, USA, by original designation.

Description

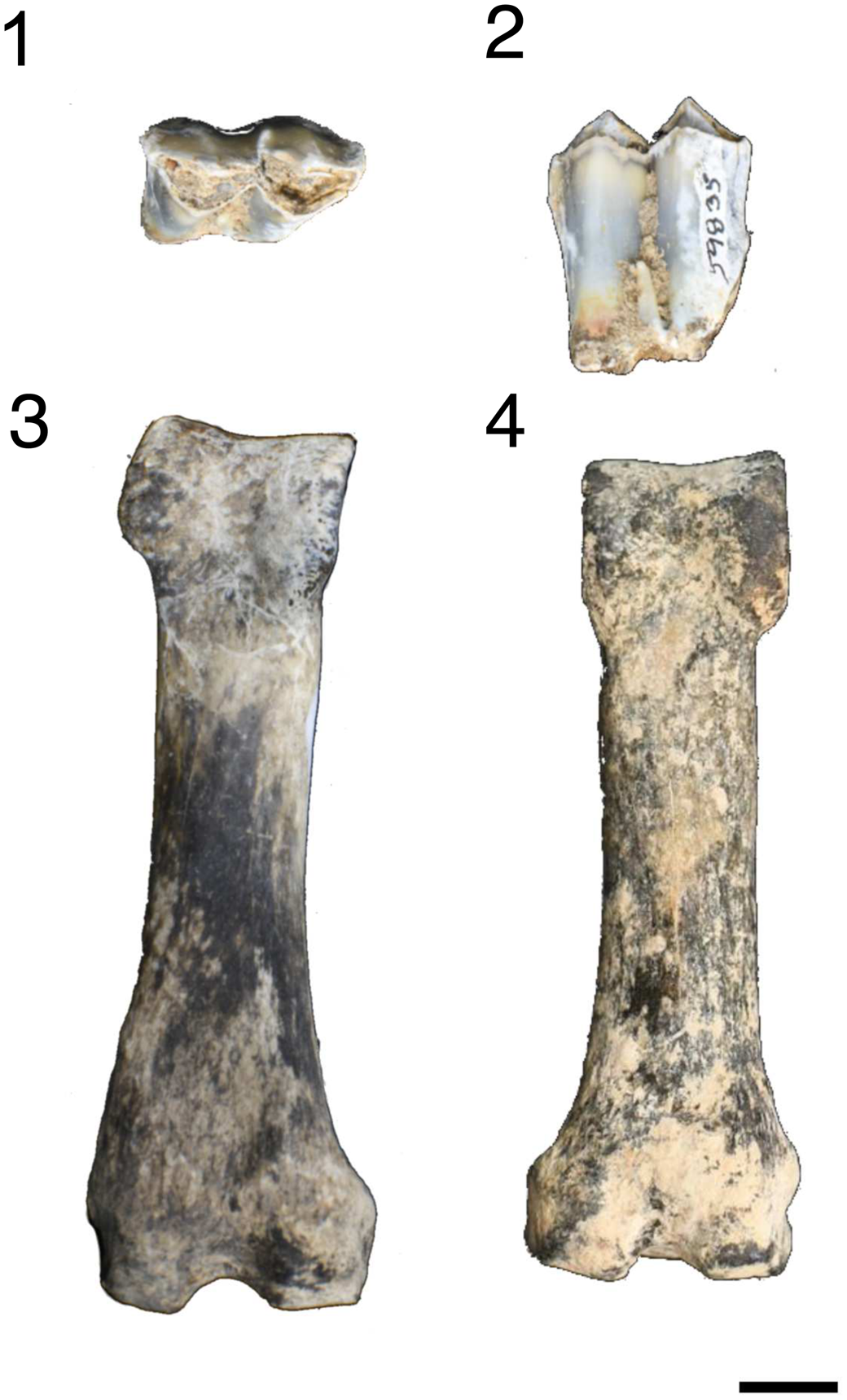

Small size of molar is consistent with Pleiolama, particularly with the small species Pleiolama vera (Matthew, Reference Matthew1909); although Pleiolama and Alforjas Harrison, Reference Harrison1979 are similar in size, lower degree of hypsodonty is consistent with Pleiolama (Webb and Meachen, Reference Webb and Meachen2004). Elongated, gracile phalanx indicates that UOMNH F-4154 and UOMNH F-81112 are referable to Lamini (Harrison, Reference Harrison1979). Presence of W-shaped suspensory ligament scar that does not extend far down the phalangeal shaft indicates that the specimens can be referred to the lamins Alforjas or Hemiauchenia Gervais and Ameghino, Reference Gervais and Ameghino1880 (sensu Harrison, Reference Harrison1979, equivalent to Pleiolama; Webb and Meachen, Reference Webb and Meachen2004). Relatively narrow proximal end of phalanx is inconsistent with Alforjas (Table 2).

Figure 4. Pleiolama sp. indet. from McKay Reservoir: (1, 2) right m1 or m2 (SDSM 59835): (1) occlusal view; (2) lateral view; (3, 4) proximal phalanges in plantar view: (3) UOMNH F-81112; (4) UOMNH F-4154. Scale bar = 1 cm.

Referred material

SDSM 59835, right m1 or m2; UOMNH F-4154, proximal phalanx; UOMNH F-81112, proximal phalanx; both from McKay Reservoir (SDSM V802, UO 2222).

Remarks

The small camelid described by Shotwell (Reference Shotwell1956) is referable to Pleiolama. Although lamins, including Pleiolama, are known from regional Hemphillian-aged sites in Oregon's Rattlesnake Formation (Fremd, Reference Fremd2010) and Washington's Ellensburg Formation (Martin and Pagnac, Reference Martin and Pagnac2009), this is the first identification of the genus from McKay Reservoir.

Family Dromomerycidae Frick, Reference Frick1937

Dromomerycidae gen. indet. sp. indet.

Figure 5; Table 2

Description

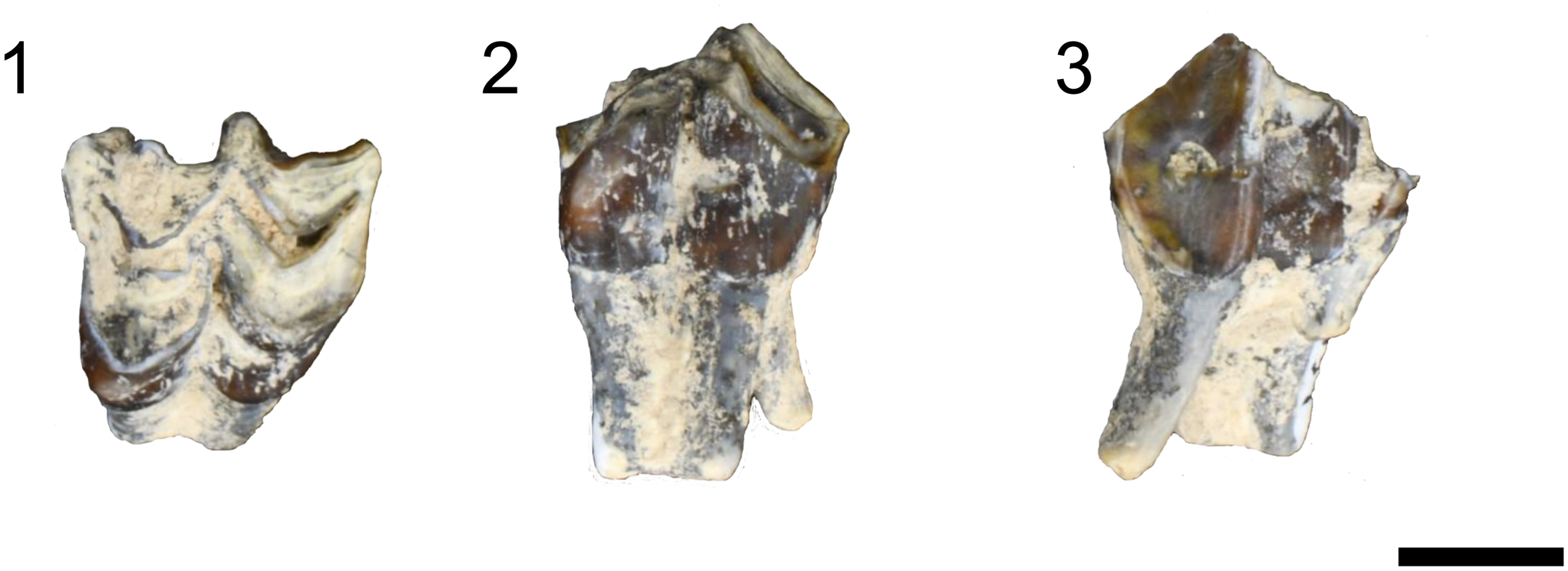

Relatively small selenodont and brachydont molar that is consistent with both Cervidae and Dromomerycidae. However, the lack of complex folding on the protoconal and metaconule crests is inconsistent with Bretzia Fry and Gustafson, Reference Fry and Gustafson1974 and other cervids (Gustafson, Reference Gustafson2015). Of the two unequivocally Hemphillian-aged dromomerycid genera (Frick, Reference Frick1937; Janis and Manning, Reference Janis, Manning, Janis, Scott and Jacobs1998), the brachydonty of the McKay Reservoir specimen is consistent with Yumaceras Frick, Reference Frick1937, but the small size of the tooth might be more consistent with Pediomeryx Stirton, Reference Stirton1936 (Table 2; Prothero and Leiter, Reference Prothero and Liter2008).

Figure 5. Dromomerycidae gen. indet. sp. indet. from McKay Reservoir, left M1 or M2 (SDSM 38459): (1) occlusal view; (2) medial view; (3) lateral view. Scale bar = 1 cm.

Referred material

SDSM 38459, left M1 or M2, from McKay Reservoir (SDSM V802).

Remarks

Isolated upper molars such as SDSM 38459 are generally not diagnostic for dromomerycids, in which lower dentition and ossicones are of predominant importance. Pediomeryx is the most common and widespread dromomerycid of the late Hemphillian, but SDSM 38459 bears a stronger resemblance to Yumaceras in its brachydonty (Prothero and Liter, Reference Prothero and Liter2008). However, its size falls well below the range reported by Webb (Reference Webb1983) in his description of Yumaceras hamiltoni (Table 2). Pediomeryx hemphillensis is smaller in size than Yumaceras hamiltoni (Webb, Reference Webb1983; Prothero and Liter, Reference Prothero and Liter2008), but a paucity of published measurements of upper dentition for this species hinders quantitative comparisons. If SDSM 38459 does represent Yumaceras, its occurrence at McKay Reservoir would be a slight range extension; it has previously only been reported in the Pacific Northwest from the earlier Hemphillian-aged Drewsey Formation of southeastern Oregon (Prothero and Liter, Reference Prothero and Liter2008). Pediomeryx has not previously been reported from the region.

Order Perissodactyla Owen, Reference Owen1848

Family Equidae Gray, Reference Gray1821

Subfamily Equinae Steinmann and Döderlein, Reference Steinmann and Döderlein1890

Equinae gen. indet. sp. indet.

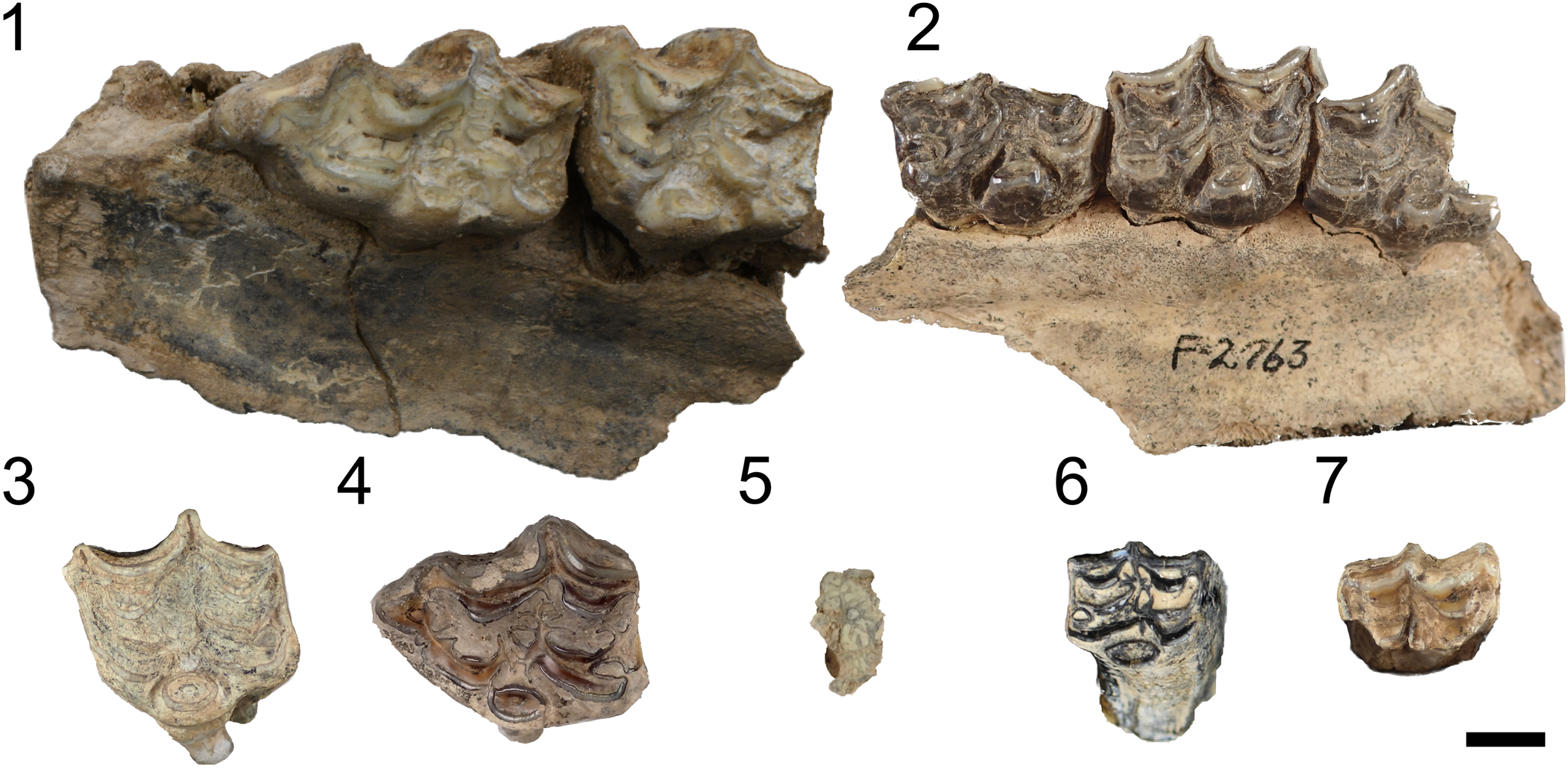

Figure 6.7; Table 3

Referred material

UOMNH F-4444, buccal half of an upper cheek tooth other than P2 or M3, from McKay Reservoir (UO 2222).

Figure 6. Equids from McKay Reservoir: (1–5) Cormohipparion sp. indet., upper dentition: (1) left maxilla fragment with P2–P3 in occlusal view (UWBM VP 61653); (2) right maxilla fragment with P2–P4 in occlusal view (UOMNH F-2763); (3) left upper cheek tooth other than P2 or M3 in occlusal view (UOMNH F-2787); (4) left upper cheek tooth other than P2 or M3 in occlusal view (UWBM VP 61573); (5) left upper cheek tooth fragment in occlusal view (UOMNH F-4156); (6) Pseudhipparion sp. indet., right upper cheek tooth other than P2 or M3 in occlusal view (UOMNH F-29959); (7) Equinae gen. indet. sp. indet., buccal half of upper cheek tooth other than P2 or M3 in occlusal view previously assigned to Neohipparion (UOMNH F-4444). Scale bar = 1 cm.

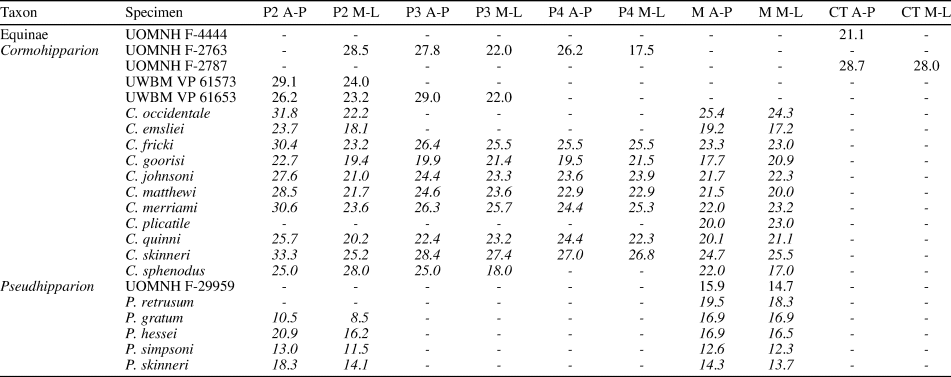

Table 3. Measurements of equids from McKay Reservoir. Anteroposterior (A-P) and mediolateral (M-L) measurements (in mm) are shown for upper premolars (P), upper molars (M), and upper cheek teeth (CT). Due to its fragmentary nature, measurements of UOMNH F-4156 (Cormohipparion sp. indet.) are not included. Mean values for the upper molars from the species description of multiple Cormohipparion and Pseudhipparion species are shown in italics, including Cormohipparion occidentale (Leidy, Reference Leidy1856) (n = 1), Cormohipparion emsliei Hulbert, Reference Hulbert1988 (n = 5 P2, 24 M), Cormohipparion fricki Woodburne, Reference Woodburne2007 (n = 6), Cormohipparion goorisi MacFadden and Skinner, Reference MacFadden and Skinner1981 (n = 4), Cormohipparion johnsoni Woodburne, Reference Woodburne2007 (n = 2), Cormohipparion matthewi Woodburne, Reference Woodburne2007 (n = 4), Cormohipparion merriami Woodburne, Reference Woodburne2007 (n = 4), Cormohipparion plicatile (Leidy, Reference Leidy1887) (n = 1), Cormohipparion quinni Woodburne, Reference Woodburne1996 (n = 14), Cormohipparion skinneri Woodburne, Reference Woodburne2007 (n = 2), Cormohipparion sphenodus (Cope, Reference Cope1889) (n = 2), Pseudhipparion retrusum (Cope, Reference Cope1889) (n = 2), Pseudhipparion gratum (Leidy, Reference Leidy1869) (n = 2), Pseudhipparion hessei Webb and Hulbert, Reference Webb and Hulbert1986 (n = 43 P2, 24 M), Pseudhipparion simpsoni Webb and Hulbert, Reference Webb and Hulbert1986 (n = 5 P2, 24 M), and Pseudhipparion skinneri Webb and Hulbert, Reference Webb and Hulbert1986 (n = 11 P2, 44 M). -, not available.

Remarks

UOMNH F-4444 is the only specimen in any collection that we could find that was identified in collections as Neohipparion. Shotwell (Reference Shotwell1955a, Reference Shotwell1956, Reference Shotwell1958) reported one occurrence of Neohipparion but never identified the specimen. This specimen is broken so that the lingual half is missing, thus removing any of the diagnostic characteristics for any more specific identification. As such, we are removing the occurrence of Neohipparion from the faunal list for McKay Reservoir.

Tribe Hipparionini Quinn, Reference Quinn1955

Genus Cormohipparion Skinner and MacFadden, Reference Skinner and MacFadden1977

Type species

Cormohipparion (= Hipparion) occidentale (Leidy, Reference Leidy1856) from the Neogene at Little White River, South Dakota, USA, by original designation.

Cormohipparion sp. indet.

Figure 6.1–6.5; Table 3

Description

Large teeth (Table 3). Protocone small and isolated; complex plications on the pre- and post-fossettes; well-developed pli caballins. More specific identification is difficult with isolated teeth because they lack a majority of diagnostic characters (Famoso and Davis, Reference Famoso and Davis2014).

Referred material

UOMNH F-2763, right maxilla fragment with P2–P4; UOMNH F-2787, left upper cheek tooth other than P2 or M3; UOMNH F-4156, left upper check tooth fragment; UWBM VP 61573, left P2; UWBM VP 61653, left maxilla fragment with P2 – P3; all from McKay Reservoir (UO 2222, UWBM C0128).

Remarks

UOMNH F-2763, F-2757, F- 4156, and UWBM VP 61653 and VP 61573 mark the first definitive occurrences of Cormohipparion in Oregon. It is likely that specimens identified as Hipparion by Shotwell (Reference Shotwell1955a, Reference Shotwell1956, Reference Shotwell1958) are Cormohipparion, because he never identified the specific specimens that he assigned to Hipparion. Additionally, Skinner and MacFadden (Reference Skinner and MacFadden1977) named Cormohipparion from material previously identified as Hipparion in North America well after Shotwell's original work. We have reviewed all of the relevant specimens and have not found any that meet the diagnosis for Hipparion and suggest removing it from the faunal list and replacing it with Cormohipparion. Measurements of these referred specimens are not consistent with the species means of previously described species (Table 3). Furthermore, for specimens with multiple teeth, the most similar species varied with tooth position. UOMNH F-2787 is most comparable in size to Cormohipparion skinneri but is still fairly far off. The dimensions of UOMNH F-2763, and UWBM VP 61573 and VP 61653 are not consistent with those of any other species of Cormophipparion. Because the numerical data are not conclusive and there are no qualitative characteristics on each of these teeth that can definitively place these specimens into a specific species, we leave these specimens identified to the level of genus.

Genus Pseudhipparion Ameghino, Reference Ameghino1904

Type species

Pseudhipparion (= Hipparion) retrusum (Cope, Reference Cope1889) from the Neogene Ogallala Formation at Phillips County, Kansas, USA, by original designation.

Pseudhipparion sp. indet.

Figure 6.6; Table 3

Description

Small tooth (Table 3). Protocone large, elliptical, and isolated in early wear stages but appears to connect in later wear stages (estimated from observance on the exterior of the tooth); simple plications on both fossettes; prominent hypoconal lake. More specific identification is difficult with isolated teeth because they lack a majority of diagnostic characters (Famoso and Davis, Reference Famoso and Davis2014).

Referred material

UOMNH F-29959, right upper cheek tooth other than P2 or M3, from McKay Reservoir (UO 2222).

Remarks

UOMNH F-29959 marks the first published occurrence of the genus in Oregon and the Pacific Northwest, as well as west of the Rocky Mountains. When the length and width of the specimen are compared to mean values for previously described species (Table 3), this tooth is not consistent with Pseudhipparion skinneri Webb and Hulbert, Reference Webb and Hulbert1986, Pseudhipparion gratum (Leidy, Reference Leidy1869), or Pseudhipparion hessei Webb and Hulbert, Reference Webb and Hulbert1986. There are no other qualitative or quantitative diagnostic features on this tooth that can be used to differentiate among the three species, therefore we leave the specimen identified to the genus level.

Discussion

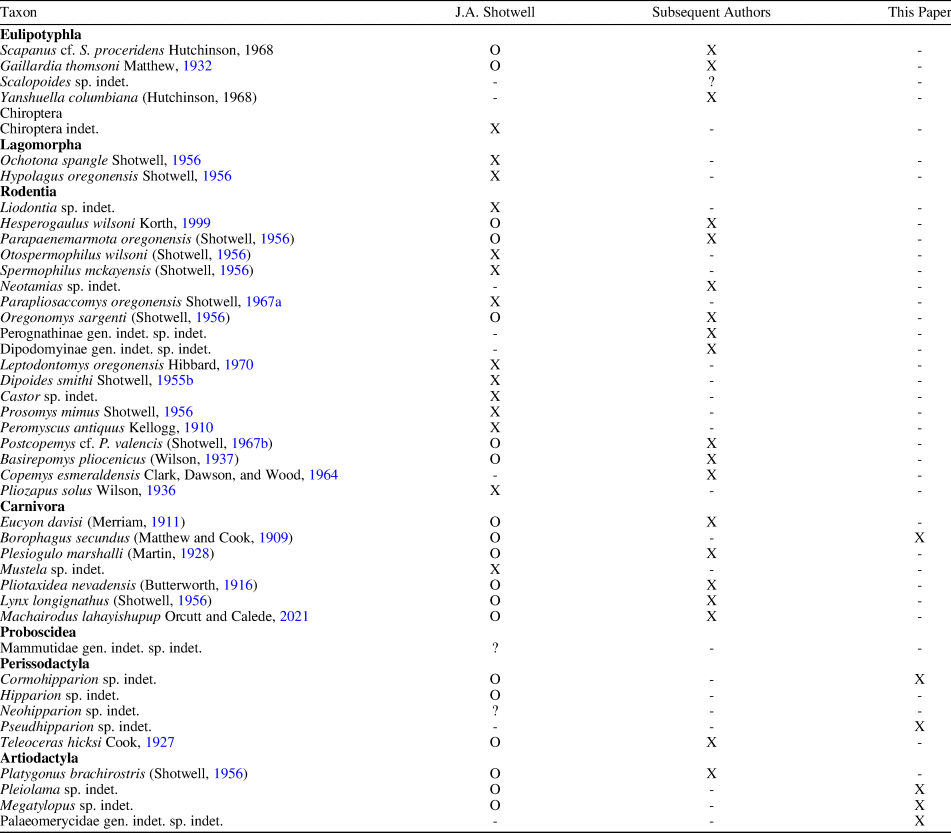

Besides adding to the McKay Reservoir faunal list, the specimens described above underscore the paleobiological significance of the site. Most importantly, these occurrences mark major geographic range extensions for three taxa (Borophagus secundus, Pseudhipparion sp. indet., and Cormohipparion sp. indet.), none of which had been definitively identified in Oregon and of which only Cormohipparion had previously been described from any sites in the Pacific Northwest (Rapp, Reference Rapp2006). Their presence at McKay Reservoir reflects the remarkable completeness of the paleocommunity and further solidifies the value of the site as a natural laboratory for Hemphillian paleoecology, a point that is illustrated by comparison with other geographically constrained Hemphillian-aged formations in the Pacific Northwest. Following this analysis, 40 mammalian taxa have been reported from McKay Reservoir (Table 4). By contrast, the Rattlesnake Formation of the John Day Basin has yielded 29 described mammalian taxa and the Thousand Creek Formation of northern Nevada has yielded 30 (https://paleobiodb.org/data1.2/occs/list.csv?datainfo&rowcount&base_name=Mammalia&strat=Thousand Creek, Rattlesnake, downloaded from the Paleobiology Database on 3 October 2023). Expanding these comparisons beyond the Pacific Northwest, McKay Reservoir's mammalian diversity is comparable to one of the sites from Texas’ Hemphill Beds for which the Hemphillian is named (Coffee Ranch, 45 taxa) and surpasses the other (Higgins Quarry, 30 taxa; https://paleobiodb.org/data1.2/occs/list.csv?datainfo&rowcount&base_name=Mammalia&interval=Hemphillian,Hemphillian&cc=US&state=Texas&county=Hemphill, Lipscomb, downloaded from the Paleobiology Database on 28 November 2023). Having better established the composition and completeness of the mammal fauna, a logical next step along with continuing field work would be reconstructing interactions between the members of that fauna through stable isotope analysis of mammal teeth. Fossils from the site could also inform broader quantitative taxonomic analyses of taxa such as Megatylopus, Cormohipparion, and Pseudhipparion, possibly allowing the identification of existing specimens to the species level.

Table 4. Updated faunal list for McKay Reservoir. Taxa first described by Shotwell (Reference Shotwell1956, Reference Shotwell1958, Reference Shotwell1967a, Reference Shotwellb) in his initial work on the locality, by subsequent authors (Lindsay, Reference Lindsay1962; Hutchison, Reference Hutchison1968; Wagner, Reference Wagner1976; Harrison, Reference Harrison1981; Martin, Reference Martin1984, Reference Martin1998; Korth, Reference Korth1999; Prothero, Reference Prothero2005; Orcutt and Calede, Reference Orcutt and Calede2021), and in this paper are shown. X, the original taxonomic assignment is still valid; O, taxonomy has been updated since its original description; ?, taxonomic assignment uncertain; -, not applicable.

The McKay paleocommunity consists of not only mammals but fish, amphibians, and an abundance of reptiles and birds, most of which have not been a focus of study since the original descriptions by Shotwell (Reference Shotwell1956) and Brodkorb (Reference Brodkorb1958). Note that, among the comparable regional formations mentioned above, the only description of any nonmammalian taxon is the turtle Clemmys hesperia Gray, Reference Gray1825 from the Rattlesnake Formation (Hay, Reference Hay1903). Given the importance of these taxa as environmental indicators, a revision of the ichthyofauna, herpetofauna, and avifauna of McKay Reservoir and other Dalles Group localities will provide a more complete paleoecological context. A clearer understanding of the physical environment of the McKay paleoecosystem is also crucial, particularly because Shotwell's (Reference Shotwell1955a) interpretation of the site as a pond-bank community is not consistent with the coarser-grained lithology of the bluff from which the fossils weather (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Hargrave and Ball2018). Along with sedimentology, stratigraphy, and paleopedology, ichnology could also provide valuable information about the McKay paleoenvironment, because burrows consistent in size with those of fossorial rodents were visible in some of the lower units of the McKay Formation. Establishing as clear as possible an environmental context would make it possible to undertake analyses not feasible in many paleoecosystems, e.g., reconstructing food webs or population-level morphological patterns in well-represented taxa including rhinocerotids, sciurids, and camelids. Additional fieldwork and the review of previously collected material is pivotal to our understanding of the McKay Formation and the Hemphillian of the Pacific Northwest, revealing a more complete picture of the fauna, providing increased sample sizes for paleobiological analyses, and allowing comparisons with coeval localities across North America.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the other members of the 2017 and 2021 field crews at McKay Reservoir: R. Delplanche, C. Vietri, E. Pratt, S. Schwartz, K. Gunther, D. Dillard, R. Gowen, R. Jessen, G. Retallack, W. McLaughlin, and J. Calede. Fieldwork was funded by the Paleontological Society's A.J. Boucot Award, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and by startup funds for JDO from Gonzaga University and the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust; thanks also to N. Staub and A. Hinz for administering these funds. E. Davis and S. Hopkins were instrumental in providing a repository for this and other McKay specimens at the University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History and facilitated access to previously collected material. K. Anderson (UWBM), P. Holroyd (UCMP), and N. Fox (SDSM) also provided collections access. Thanks to D. Pagnac (SDSM) for discussions relating to equids from McKay and the Pacific Northwest. B. MacFadden and an anonymous reviewer provided helpful reviews of early versions of this manuscript. The Paleontological Investigation Permits and Special Use Permits that allowed collection at McKay were issued by W. Hurley and M. Bovee (US Bureau of Reclamation) and L. Glass and K. Lopez (US Fish and Wildlife Service). The Kennedy family graciously allowed us access to the site through their property. McKay Reservoir is located on the traditional lands of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare none.