You're the first to arrive at the archaeological site, just as the sun is rising. You see, with a mixture of delight and sorrow, that most of the artifacts that were stolen have indeed been returned. Some are in the trenches, and some are wrapped in newspaper and loosely packed into old wine boxes.

The Venus mosaic once again rests on the floor of your archaeological trench, but it has been sawed into jagged pieces, each one roughly sized to be framed and put up on someone's living room wall.

As you open one of the boxes and begin to take out the hastily packed items, you find some in good shape, but others appear to have been intentionally broken – perhaps because they're easier to smuggle or sell that way. You carefully consider your response to Dr. Forza and the Carabinieri. You think of the importance of preserving dig sites, knowledge, and artifacts; you think, too, about your promise to Fede and what could happen to her, as well as to her father.

You realise there is no easy answer. In the end, you decide to:

(a) tell Dr. Forza and the Carabinieri that you showed Fede the dig site the night before the tombaroli (tomb robbers) raided.

(b) tell Dr. Forza and the Carabinieri that, unfortunately, you don't have any helpful information for them.

(c) evade Dr. Forza and the Carabinieri, at least for now, and immediately confront Fede yourself.

The above passage comes from the last chapter of the online, game-based course, Rome: The Game, cross-listed in the History of Art & Architecture Department and the Writing Program at the University of California, Santa Barbara. In the game, which features a choose-your-own-adventure-style interactive narrative, undergraduate students play the role of a graduate student who is sent to Rome by a Getty Museum curator in order to solve a mystery involving an ancient statue found in the museum's storeroom. Along the way, the student (or player) visits local museums and areas of cultural interest, gives tours of ancient Roman monuments and sites, becomes a trench supervisor on an archaeological excavation, and encounters the shadowy world of the tombaroli (tomb robbers) and the mafia-run black market for antiquities. Rome: The Game is a fully online course presented as an adventure game; it is organised in chapters (nine chapters total, covering the ten-week quarter) with all course materials (e.g., readings, videos, podcasts, etc.) and assessments embedded within the world of the game.

In the following discussion of Rome: The Game, we explain the rationale and methods for creating a class in this style, the mechanics of the course itself, the research that informed the design of the course, student experiences, and learning outcomes. Citing relevant research in several fields – such as game studies, educational psychology, and communication studies – we argue that creating an online course in the style of an interactive, narrative digital game presents a model for immersive and effective active learning in an online environment.

Choose-your-own-adventure

In the passage quoted at the beginning of this article, the student has – in the game – just finished working at an archaeological site and has witnessed first-hand the looting and destruction of artifacts from the excavated site. The student realises that a close friend named Federica (nicknamed Fede) tipped off the tombaroli (tomb robbers).Footnote 1 The choice the student makes involving how to deal with Fede leads to one of several paths in the story, each with its own set of specific consequences.

Player choices like this one are at the core of Rome: The Game. Footnote 2 The branching narrative of Rome: The Game is similar to that of the Choose Your Own Adventure books, a popular and influential series of interactive books first published in the 1970s by Bantam Books.Footnote 3 This style features a narrative crafted in the second-person point of view, allowing the reader to step into the role of protagonist and assume a measure of control over the shape of the narrative.

Choices the student makes in Rome: The Game can be seen as assessments. Some choices are related to embedded readings, testing students' knowledge and memory of the information presented, much like a multiple-choice question after an assignment; other choices are related to images of art and architecture or to city maps, asking students to choose a route, for example, in order to demonstrate their knowledge of the topography of Rome. Choices may also involve the information presented in an embedded video that students have just watched, with students formulating questions to ask a character in the story to learn more about the city. Or choices can, as in the passage at the beginning of this article, ask the student to reflect on the consequences of the illicit looting of cultural property through participation in a realistic scenario. In all these cases, when the student makes a choice, the narrative takes a turn down one of several branches, presenting a specific storyline and consequences. If the student's choice is based on a misunderstanding of the material, the game responds with relevant information, as well as new chances to make different choices, offering the student the opportunity to learn from past ‘mistakes’.

Course rationale: why the game format?

In a world before Covid-19, just before many institutions were forced into the hasty adoption of remote learning, we designed Rome: The Game to function as a more accessible and engaging alternative to traditional large lecture courses.Footnote 4 At our home university, physical classroom space was growing tighter every year as student enrollments were increasing – an added incentive. But most importantly, we felt this course could take advantage of a number of the unique attributes offered by the digital medium. When we first starting designing this course, Zoom had yet to become the default virtual classroom; flipped classrooms were concepts that were generally not implemented at scale within our university, especially outside the STEM fields.Footnote 5 But the Covid-19 pandemic shaped (and continues to shape) higher education's experience with online teaching, as both students and educators have become increasingly familiar with the disadvantages and the advantages that come with different implementations of online learning (D'Agostino, Reference D'Agostino2022; Müller and Mildenberger, Reference Müller and Mildenberger2021; Peters et al., Reference Peters, Rizvi, Mcculloch, Gibbs, Goror and Hong2020; Saichaie, Reference Saichaie2020). In this continually changing educational landscape, we argue that Rome: The Game goes beyond conventional virtual learning to offer an engaging and effective model for online teaching.

As in a flipped classroom, the course content and materials in Rome: The Game – its ‘extra-curricular instruction’ (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Lin and Hwang2019) – are all delivered asynchronously. Students play through the interactive narrative, which includes responding to the embedded readings and other course material, on their own schedules throughout the week. Students then meet once a week in a synchronous, 25-person, TA-led, 50-minute Zoom section to engage in group activities based on that week's course content.Footnote 6

In addition to the method of content delivery and to the allocation of course time and course materials, Rome: The Game, in shifting the paradigm from teacher-centred toward student-centred learning, incorporates the most essential aspect of the flipped classroom: active learning.Footnote 7 Here we follow Prince's definition (Reference Prince2004, 1) of active learning as ‘any instruction method that engages students in the learning process…[it] requires students to do meaningful learning activities and think about what they are doing.’Footnote 8 While some proponents of active learning prioritise in-class activities and discussions (for example Bonwell and Eison, Reference Bonwell and Eison1991; Prince, Reference Prince2004),Footnote 9 we argue that the independent, interactive narrative for our course is the activity that most promotes student engagement.Footnote 10 Furthermore, the game format offers a novel way to put students at the centre of the experience in which they can actively engage in ‘meaningful learning activities and think about what they are doing’, by considering the choices they make as well as the consequences of those choices (Bonwell and Eison, Reference Bonwell and Eison1991, 2). And putting the student in charge of the direction of the narrative helps develop ‘an emotional commitment… to integrate new knowledge’ (Drake, Reference Drake2012, 43).

Course style and mechanics

Not only the choices but also the range of media – videos, podcasts and other audial experiences, mini-games, images, interactive websites, texts – embedded in Rome: The Game fosters active learning. (A sample passage from the game with branching paths is accessible here.Footnote 11) Students are highly motivated to complete the course readings – which include excerpts from textbooks about archaeology, current newspaper articles about the antiquities trade, historical fiction, essays about the art and architecture of Rome, passages from ancient Latin literature (in translation), or descriptions of antiquities on auction-house websites – as they occur in the interactive narrative, because successful choices can only be made with knowledge gleaned from the readings and other course materials.

Other course materials include embedded videos, which are also tied to choices in the narrative, and are filmed from the first-person perspective, so students feel that they are actually walking through these sites or museums. The videos include tours of ancient Roman monuments and museums, such as the Roman Forum, the Colosseum, the Pantheon, and the Montemartini Museum. There are also interactive videos in which students, for example, decide which statues they wish to learn more about in the Getty Villa Museum; other interactive vidoes allow students to choose different paths leading to specific ancient monuments as they race through the streets of Rome on a Vespa.

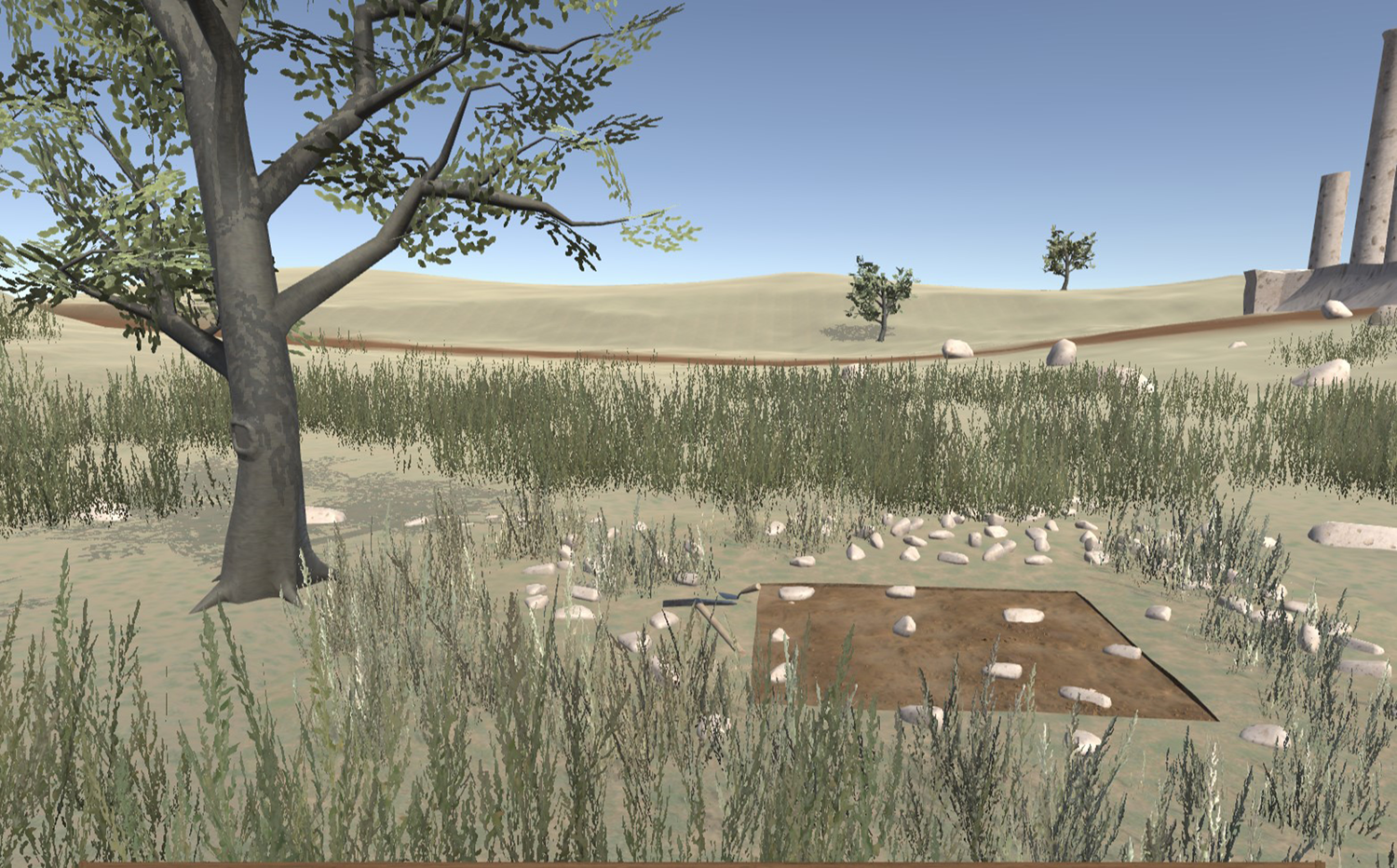

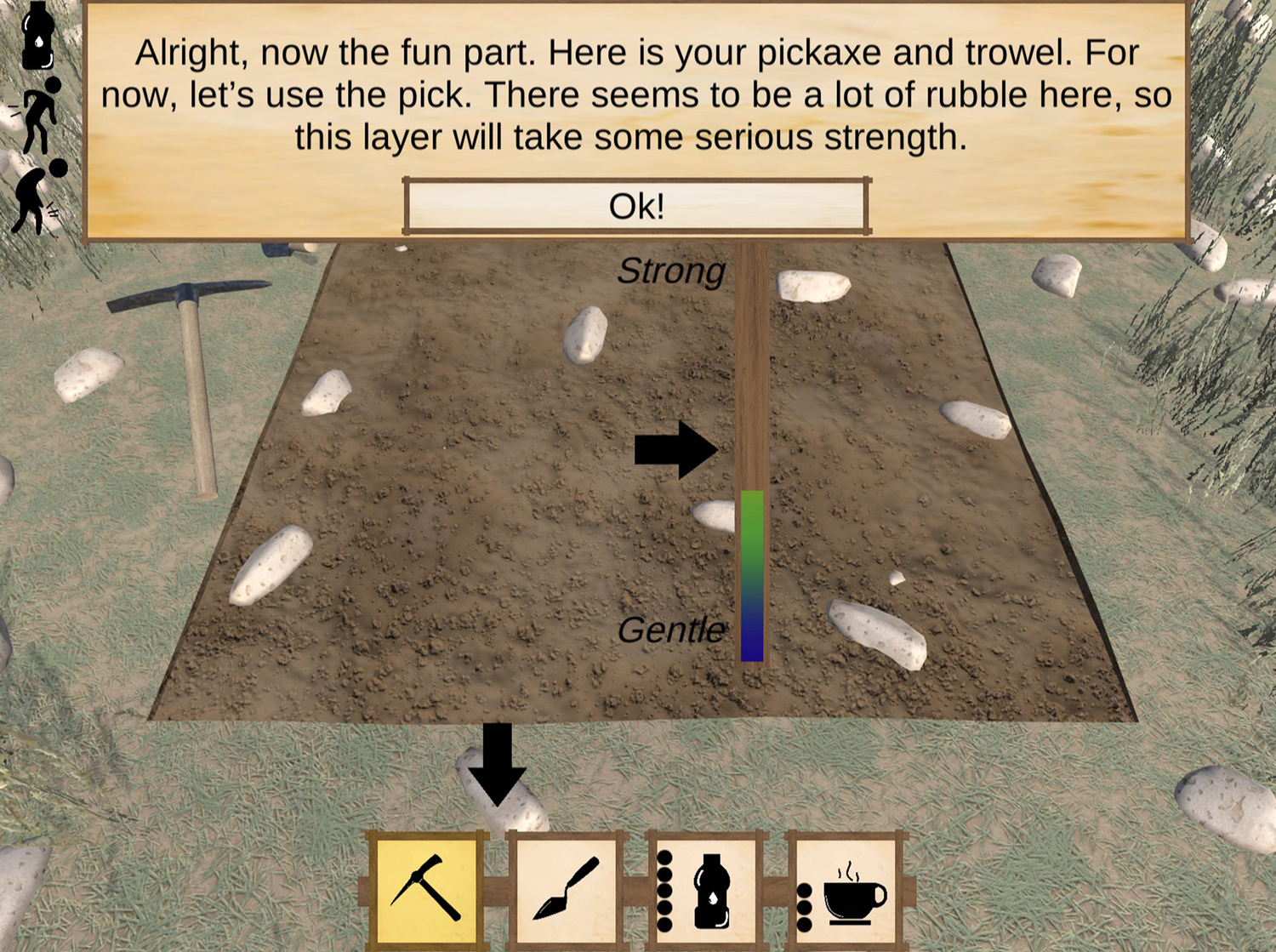

The embedded digital archaeological dig mini-game (created by a team of expert designers and programmersFootnote 12) looks and plays more like a traditional 3D video game than does the main interactive narrative created in Twine. It allows students to participate in all steps of the archaeological process – from staking out a trench (with a ruined Roman temple in the background) (Figure 1), to selecting a pick or trowel to excavate, to determining the force with which to wield the chosen tool (Figure 2), to documenting the site and recording different layers, or strata, excavated and the artifacts found (with photographs and context sheets). Students learn the importance of stratigraphy through the game. Additional aspects of an archaeological excavation – the need for water (and coffee!) breaks, back pain and knee pain while digging in the hot Italian summer sun – are also elements of the game. Along the way, students uncover roof tiles, coins, fragments of frescoes and amphorae, bones, and at the deepest layer, a well-preserved mosaic of the goddess Venus and her son Cupid (who bears a striking resemblance to the mystery statue!) (Figure 3). The first-hand experience of (virtually) excavating an archaeological trench allows students to apply what they have learned through the readings, videos, podcasts, site visits, and interactive conversations with characters in the narrative.

Figure 1. Site of Casavenere, excavation mini game.

Figure 2. Tool selection from excavation mini game.

Figure 3. Mosaic of Venus.

Assessments

Just as course materials (such as readings, videos, and the archaeological mini-game) are embedded within the interactive narrative, so too are the assessments. The course is cross-listed between the History and Art & Architecture Department and the Writing Program, and each assessment is designed to meet learning goals of each discipline. The midterm exam is delivered as four video questions (with transcripts) asked by the archaeological ‘soprintendente’ (in the story her name is Dr. Forza, the character in charge of granting excavation permissions in the area in which the student hopes to excavate). In the 'interview’ with Dr. Forza (which again, takes the form of video midterm questions) the student needs to impress the soprintendente in order to get permission to excavate. The intention here was to include an emotionally resonant aspect of the story to encourage students to engage in a heightened way with the course material during the midterm.

In addition to the midterm exam, weekly writing assignments also take place within the world of the game, and are presented at the end of each chapter. Each writing assignment focuses on a different genre of writing – blog post, podcast script, travel magazine article, museum catalogue entry, historical fiction, academic essay, excavation journal entry, and social media post. In TA-led sections preceding each assignment, students study the particular genre of writing that they will need to produce the following week, analysing, for example, the genre conventions, target audience, purpose, and larger context of a sample blog or sample Instagram post.

These weekly low-stakes assignments are designed to increase students' genre awareness and writing skills, and also to prepare them for the course's final paper. By the end of Chapter 1, students know what the final, and main, assignment for the course will be: they will report back to the Getty Museum, making an argument built on evidence culled from the game, related to what they believe is the original context, provenance, and purpose of the mystery statue. Students also must argue whether the statue should stay at the Getty Museum or be returned to Italy. Students can choose to compose this final report in any of the nine genres that they have studied and practised working in throughout the course. In their writing, students are asked to pay particular attention to context, purpose, and the use of genre conventions, but they have the freedom to explore crafting their report in something other than the traditional academic essay format as long as their writing meets the requirements of the assignment: a visual analysis of the mystery statue; a comparison to other statues and contexts seen in the story; a discussion of one monument or site visited; a theory about the original placement and function of the mystery statue; and an argument addressing whether or not the statue should be returned to Italy.

Do learning games work?

Autonomy, choice, and game design

The final paper assignment, mentioned above, was designed to give students a high degree of autonomy by allowing them to write in any of nine different genres they study in the course. Choice is, of course, also one of the main components of the overarching narrative of the game, as students are able to decide what their character says or does at important moments, which then spins the narrative off into different directions. But while many educators may be convinced of the effectiveness of offering choice as a way to support student empowerment and active learning, some may wonder whether the context we're working with – that of digital games – can effectively promote learning.

The body of research that addresses this question is large and complex, but a comprehensive meta-analysis on digital games and learning (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Tanner-Smith and Killingsworth2016) provides an overview. With data accumulated from a large number of studies over a period of several years on digital games used in learning contexts, Clark et al. (Reference Clark, Tanner-Smith and Killingsworth2016) concluded that games were, on average, significantly more effective than traditional teaching methods (e.g., lectures, readings, ‘drill and practice’ exercises) at enhancing students' cognitive processes and strategies, knowledge, and creativity. Digital games used in learning contexts were also found to significantly increase students' motivation, intellectual openness, work ethic, conscientiousness, and positive ‘core self-evaluation’.Footnote 13

The game elements we focused on in Rome: The Game are the narrative and choices which afford students significant control over what their character says and does. One study noted that course designers often shy away from including the extra content that choices require (although we believe that using a choose-your-own-adventure-style format can make course design compelling for both instructor and learner!) and therefore experimented with a ‘feigned choice’ option (Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Nebel, Beege and Rey2018). The feigned choice appeared to offer students the option to read a text on ‘social science’ or ‘natural science’. In reality, regardless of what students chose, they were led to the exact same text, which incorporated equal amounts of social and natural science. Students involved in the study appear to have believed the choice had a real effect, as no participants who were offered the feigned choice reported dissatisfaction with the content of the learning text or choice. The study's authors concluded that even these feigned choices enhanced retention of knowledge and transfer performance (learning scores), as long as the choices were relevant to learning goals.Footnote 14

Game narratives

Alongside choices, narrative, too, can be a powerful educational tool. As Armstrong and Landers (Reference Armstrong and Landers2017) state, narrative used in games has been linked to increases in knowledge and motivation.Footnote 15 However, Armstrong and Landers (Reference Armstrong and Landers2017) are careful to point out that studies which are able to truly isolate narratives in games are rare. This may be because a well-crafted game narrative is usually deeply entwined with other game elements (as we hope we have accomplished in our design of Rome: The Game), and when game elements are working intimately together, it can be difficult to accurately pinpoint the effects of individual components.

There is another reason to believe that the basic design of Rome: The Game – with its emphasis on narrative and choices that allow the student to have a measure of control over the main character's actions and the plot – is effective for learning. A study of the choose-your-own-adventure style book, The Brewsters (which uses narrative and choices to teach ethics and professionalism to students preparing to become health care providers), showed that students increased their knowledge significantly by reading/playing The Brewsters, while also rating the activity positively (Rozmus et al., Reference Rozmus, Carlin, Polczynski, Spike and Buday2015).

Standalone narratives, without any interactivity, have also been studied in great depth from a number of different perspectives. Of particular consideration in our design of the narrative in Rome: The Game is Green and Brock's (Reference Green and Brock2000) study which argues that narratives have a unique ability to speak to audiences because of their similarity to direct personal experience, and because narratives elicit strong emotions toward characters.Footnote 16 Green and Brock (Reference Green, Brock, Green, Strange and Brock2002) also suggest that narratives which immerse, or transport, audiences can promote belief change.Footnote 17 Researchers have also argued that immersive stories might be particularly helpful learning tools in that they are capable of reducing resistance, aiding with the processing of new, complex information, and provide social connections and role models for behaviour change (Green, Reference Green2006; Kreuter et al., Reference Kreuter, Green, Cappella, Slater, Wise, Storey and Woolley2007; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Frank, Chatterjee and Baezconde-Garbanati2013). For example, Murphy et al. (Reference Murphy, Frank, Chatterjee and Baezconde-Garbanati2013) showed that a fictional narrative film had greater impact on knowledge, attitudes, and behavioural intention in audiences than information presented in a non-fiction, non-narrative format. The authors found that transportation (immersion), identification with characters, and emotion contributed to knowledge and to positive changes in attitude and behavioural intention; the authors also note that their findings support the argument made in recent years by an increasing number of researchers (see, for example, Houston et al., Reference Houston, Allison, Sussman, Horn, Holt, Trobaugh, Salas, Pisu, Cuffee, Larkin, Person, Barton, Kiefe and Hullett2011; Larkey and Hecht, Reference Larkey and Hecht2010; McQueen et al., Reference McQueen, Kreuter, Kalesan and Alcaraz2011; Robillard and Larkey, Reference Robillard and Larkey2009; Unger et al., Reference Unger, Cabassa, Molina, Contreras and Baron2013) that ‘narratives and storytelling may be particularly effective for minority populations and racial/ethnic groups with a rich tradition of storytelling’ (Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Frank, Chatterjee and Baezconde-Garbanati2013). Our home university is a Hispanic-serving institution with a large number of first-generation students: one of our expectations for Rome: The Game is that the featured narrative format might speak to these students.

Furthermore, the format of the game allows students, in effect, to be instructors. The idea here is to have students learn, in part, through teaching. Research has shown that teaching others is itself an effective learning strategy, since preparing to teach, and then engaging in the act of explaining, leads to large gains in short and long-term learning (Fiorella and Mayer, Reference Fiorella and Mayer2014).Footnote 18 In Rome: The Game, in their role as graduate student supervisors, students instruct characters (undergraduates) in the narrative working under their supervision on the archaeological dig; they teach these characters about archaeological methods and about the issues surrounding looting. We hope that this type of roleplayingFootnote 19 will also have the effect of demystifying graduate school, convincing first-generation students and others who may feel that graduate school is too unfamiliar or unattainable, that it is indeed within their reach.

Emotions and learning

Eliciting emotions through a narrative can also aid learning, as the health-related narrative study detailed above shows (Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Frank, Chatterjee and Baezconde-Garbanati2013). Tyng et al. (Reference Tyng, Amin, Saad and Malik2017) echo this finding, adding that it is specifically the increased attentional and motivational components of emotion that have been linked with heightened learning and memory.

Providing an emotional experience for students, then, became one of our main goals when we were designing the narrative for Rome: The Game. We also wanted to make sure that the narrative's focus stayed squarely on the learning goals, attempting to use emotional moments to punctuate the most important of those goals. In order to do this, we decided to begin the interactive narrative by presenting students with a mystery that would rouse their curiosity: in Chapter 1, players are asked to go to the Getty Villa Museum to inspect a mysterious ancient Roman statue – which looks like a sleeping boy – that has been locked away in the museum's storeroom for decades (Figure 4). Students then (in the game) travel to Rome to investigate the provenance and function of the statue. As students explore the city of Rome and visit sites (e.g., temples, bath complexes, villas, gardens, tombs) where different types of statues were used for different purposes, students begin to form theories as to where, and for what purpose, the mystery statue was originally created.Footnote 20 Each site visit is accompanied by descriptive texts, maps, images, audio files, and videos. This rich context is designed to aid with immersion; and immersion or transportation can increase the impact of the narrative (see Green, Reference Green2006 for a discussion of immersion and narrative impact).

Figure 4. Mystery Statue from Getty Villa Museum.

Once we felt our students were hooked with a compelling reason (i.e., to solve the mystery) to pay attention to statues and their contexts, our next step was to infuse the interactive story with emotional character relationships and situations. In this attempt, we took inspiration from the process that the writers and designers at the renowned video game studio, Telltale Games, went through when creating the popular narrative-driven game The Wolf Among Us (2014). At the time The Wolf Among Us was created, Telltale Games was just coming off the success of The Walking Dead: A Telltale Games Series (2012), which won the BAFTA Games Award for Story, as well as several other awards, and was known for its intensely emotional storytelling. According to Ryan Kaufman, who was creative lead on The Wolf Among Us, the first iteration of the game was plot-heavy, focusing largely on a mystery, but people who play-tested this version did not respond to it emotionally (Thomas, Reference Thomas2021). This was a disappointment to the writers and designers, who were seeking to elicit the same kind of intense emotions that their previous game, The Walking Dead: A Telltale Games Series (2012), had done. So, the writers and designers at Telltale Games started over, retaining the mystery component, but this time, giving it a secondary role. The main goal of the new iteration of The Wolf Among Us became the characters: the gut-wrenching problems they faced, and perhaps most importantly, the way the characters treated, or mistreated each other – an aspect of the game that was intended to elicit intense emotions in players.Footnote 21

We took a similar approach in the design of Rome: The Game in that we created a mystery for students to solve, but we also leaned heavily on the student's relationship with other characters in order to elicit the most intense emotions. In Chapter 2, for example, the student meets a character who is an Italian graduate student named Federica (Fede, for short). Fede shows the student around the city of Rome, its museums and monuments, and is a friendly companion for conversations about Roman art, architecture, and culture, as well as theories involving the mystery statue. Fede also, the student comes to understand, has recently lost her brother and is struggling to support her father (who is grief-stricken and out of work) on the small stipend she receives from her university. Not long after learning this, the student invites Fede to visit the archaeological site where the student has found several artifacts, including a beautiful mosaic depicting the goddess Venus and her son Cupid. As seen in the passage at the start of this article, the morning after Fede's visit, the student returns to the dig site and finds that it has been pillaged by tombaroli (tomb robbers). Dr. Rosella Forza (another character previously mentioned in the discussion of the midterm exam) gives the player reason to believe that Fede told the tombaroli about the dig site: the student then is given a series of choices that involve trying to retrieve some of the artifacts, and deciding whether to help Fede, or turn her in.

Fede's betrayal and the loss of the mosaic (that the student personally excavated) are meant to elicit emotions in a part of the narrative that is focused on one of the main learning goals in Rome: The Game, which involves the looting of antiquities and destruction of sites that have archaeological and cultural importance. We wanted students not just to understand on an intellectual level the complex reasons behind the looting of antiquities and the horrific damage that looting causes to both the objects themselves and to archaeological contexts, but we also wanted students to feel the tragedy in a personal, visceral way such that, should the opportunity arise, students might choose to be active parts of the solution to this problem – or to be parts of the solution to other problems that are similar in ethical terms.

Alongside supporting learning goals, narratives can also help create a sense of social connectedness – which instructors sometimes struggle to do in the classroom, and perhaps even more so, in online learning environments. In ‘Using Imaginary Worlds for Real Social Benefits’, the authors give an overview of research into the way narratives impart a sense of belonging, partly because when people are immersed in story worlds, they have parasocial relationships with characters (Gabriel et al., Reference Gabriel, Green, Naidu and Paravati2022). These relationships create a real sense of belonging that protects against the effects of loneliness, rejection, and social isolation, and increases mood and life satisfaction.

Student experiences and outcome

In line with the research just discussed, the intention behind the design of the narrative and choices in Rome: The Game was to immerse students inside a rich interactive world that encourages students to engage with and retain information more effectively, to feel more invested in the course and its assessments, and to reflect meaningfully on course material. We have not conducted any experiments under laboratory conditions to try to determine how effective the evidence-based design of Rome: The Game is in promoting learning outcomes. We do, however, have student comments, which shed some light on student experiences with the game. The course has, to date, had four occasions on which students have anonymously evaluated the course: two midway through the quarters that we, as instructors, initiated, and final evaluation forms administered through the University at the end of the quarters. These evaluations help reveal how students experienced the connection between the narrative and the choice elements of the course and their own learning.

Narrative

In the anonymous evaluations, students frequently commented on their sense that the narrative structure of the game helped them remember material and enhanced their feeling of investment in their own learning. The charts below show the results (2022, 2023) of mid-quarter surveys with the questions: (1a, 2022; 126 responses) ‘Do you find the game/story format of this course to be effective?’ (Figure 5) and (1b, 2023; 49 responses): ‘Do you find the story format of this course to be effective? Why or why not? Does it have an effect on how you absorb course material?’ (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Chart 1a: Narrative-Game Format.

Figure 6. Chart 1b: Narrative-Story Format.

The following are examples of student comments from these two surveys on the course narrative, which echo research cited above regarding the affordances of narratives used in learning contexts (emphasis our own):

‘Because it is a story format, it makes me want to keep reading through and learn more about these concepts to follow along in the story, and makes learning easier’ (2022).

‘It's easier to remember story narrative than specific facts. I can make connections between the narrative and the information to help remember the information better’ (2022).

‘The story of the course kept me engaged which allowed me to remember and understand the topics more. So when it came to writing on the various artifacts and themes it was easier to start writing and thinking of ideas’ (2022).

‘The immersive nature of the story helped keep interest and fascination’ (2022).

‘I feel that having a story that we can personalise with our input is great for keeping us engaged. This format is much more informative – because I am going through it with a first person point of view, I am retaining the information much better than when I am lectured at’ (2023).

‘I find that when I am in the mind of the grad-student and am actually picturing myself in Rome reading the texts, I absorb the information a lot better and take better notes. I like how personal it is and find the story format really engaging’ (2023).

Students frequently noted how the story elements made them feel personally invested in the course material, also echoing research cited in the above section:

‘It makes me pay attention because I feel like the story is centred around me’ (2022).

‘It makes it feel like the content has more real-life applications’ (2022).

‘Information resonates with me more because it feels more important to absorb and understand when I am actively playing the role of someone who is involved in this type of work’ (2022).

‘I feel like the story format of the course does help me feel more engaged personally. Rather than having to just read article after article for a class, it's a lot more fun and engaging to me when it connects to the story and I can then apply it in the game as well…feeling like I actually am playing a part in this story’ (2023).

‘I feel that having a story that we can personalise with our input is great for keeping us engaged’ (2023).

Choices

As discussed in the previous section, including choice within courses has been shown to enhance learning (see, for example, Patall et al., Reference Patall, Cooper and Robinson2008, Reference Patall, Vasquez, Steingut, Trimble and Pituch2017; Reynolds and Symons, Reference Reynolds and Symons2001), and is, for us, intrinsic to student-centred learning. Since choices are a key component of the format of the course, we wanted to see if students felt the interactivity of the story helped them to engage more deeply with the material and to absorb the information better.

The following charts show student responses in two mid-quarter surveys (2022, 2023) to the two questions: (1a, 2022; 126 responses) ‘How does learning through the game/story format affect how you absorb course material?’ (Figure 7) and (1b, 2023; 51 responses): ‘Does the interactivity (for example, choices and interactive videos) affect your learning? If so, how?’ (Figure 8).

Figure 7. Chart 1a: Retention of material.

Figure 8. Chart 1b: Interactivity.

Examples of student comments supporting the importance of choice for student retention, autonomy, and motivation include the following (emphasis our own):

‘I think that having the interactive choices make you think about what you have just read, heard, or seen so that you remember it for later’ (2022).

‘Choices within the story makes it so I feel invested with the character and my learning’ (2022).

‘I think the course allowed me to make a lot of decisions in regard to how I wanted to learn the information, which was really interesting and insightful!’ (2022)

‘I feel like being able to make choices makes me want to remember prior details and information more, which makes me therefore pay more attention’ (2023).

‘The interactivity helps keep me engaged in the topics and forces me to think before I answer. I honestly really appreciate my knowledge being challenged as it gives confirmation I know what learned or that I need to review’ (2023).

‘The interactive videos do affect my learning, as I feel encouraged to pick the choices that will result in me obtaining more knowledge. Also being asked questions keeps me active which is why I like when I have to answer questions about something I just read’ (2023).

In addition to the feeling of investment, students repeatedly commented on the ‘quiz’ aspect of some of the choices, as components that helped them pay attention and retain information more efficiently:

‘I think the dialogue choices at the end of a page allow me to recap and review information presented’ (2022)

‘… allowing me to make choices forces me to actively read’ (2022)

‘We can test what we actually know and remember when we click the answer’ (2022).

‘Some of the choices are based on if you read the readings and watched/listened to videos so it really makes me pay attention’ (2022).

‘I feel like the different choices are a unique way to test my knowledge or understanding of the texts since it will correct me if I'm wrong’ (2023)

‘The choices make me actually think and recall what I have read and the videos + allow for a more visual sense of what we are looking at’ (2023).

In these select student comments from mid-quarter and final evaluations, which are representative of the majority of student evaluations from the course as shown in the charts above, students repeatedly signal out narrative and interactivity as key components in their learning. It should be noted that student assessments too reflected this level of retention and investment, with high marks on the weekly writing assignments, midterm exam, and final papers and strong evidence of student commitment, creativity, and retention of knowledge.

Next steps and the future of game-based learning

If certain aspects of Rome: The Game can be considered essential to an effective model of online, game-based, active learning, what does this imply for the future possibilities for online, interactive learning? Our own university is increasing enrollments, with classroom space becoming ever more limited. Other universities are seeking to engage learners who prefer asynchronous, remote options. We argue that the game-based model offers an alternative not only to a large in-person lecture course but also to the flipped classroom model.

For course designers and instructors who are trying to reach students who come from cultures with traditions rich in storytelling (or if the instructors themselves enjoy using stories to teach), we have found this to be an exciting and provocative approach to online course design, a model in which both instructors and students literally play to teach and learn.