Introduction

Clinical trials yield the vast majority of discoveries that are translated into practice. The importance of the rigor of the research and scientific integrity of data collected necessitate regulatory processes and a highly trained workforce to conduct research in accordance with these processes. Although these processes are clearly laid out for drug, device, and biologic clinical trials, the same is not always true for behavioral intervention studies. Behavioral intervention studies have not typically been held to the same intensity of regulation as drug, device, or biologic trials and thus the processes to conduct high-quality behavioral research have not been well specified. This may be because behavioral intervention studies tend to involve low risk to participants. In addition, any deliverables that result from these behavioral studies, such as specific behavioral intervention protocols, usually do not require regulation by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which is required for drugs and certain devices.

Recently, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) revised their definition of clinical trials to include behavioral research. Clinical trials are defined as “a research study in which one or more human subjects are prospectively assigned to one or more interventions (which may include placebo or other control) to evaluate the effects of those interventions on health-related biomedical or behavioral outcomes” [1]. This new definition in which behavioral intervention studies are being called “clinical trials” is a paradigm shift in social and behavioral research. This shift demands competence in new professional domains for research teams. Thus, the need for competency-based training for investigators and clinical research coordinators (hereafter referred to as coordinators) of behavioral clinical trials is urgent. When engaging in drug, device, or biologic clinical trials, investigators and coordinators require training in Good Clinical Practice (GCP). This type of training is based on an international standard to ensure participant safety and data integrity, as well as to ensure consistency in reporting and regulation. Investigators and coordinators of behavioral clinical trials have not typically been required to undergo this training, as evidenced by a recent review from the GCP Training Project by the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative [Reference Arango2]. Because GCP training was designed for drug, device, and biologic trials, a need was identified to examine how GCP training relates to social and behavioral research and particularly in the conduct of behavioral trials.

Other papers in this issue have discussed the background of the Enhancing Clinical Research Professionals’ Training and Qualifications (ECRPTQ) project, recommendations for training, and the process for defining competencies for study investigators and coordinators. This paper will present the process the Social and Behavioral Work Group undertook to determine how GCP relates to the conduct of behavioral clinical trials. This was done for the purposes of developing an e-learning course for best practices training in social and behavioral interventional research.

Materials and Methods

Formation of Social and Behavioral Work Group

The initial ECRPTQ meeting was held in Chicago to bring representatives of all 62 Clinical Translational Science Award (CTSA) hubs and key stakeholders in the human subject clinical research area together to adopt a standardized approach to GCP training for clinical trials. The attendees determined that an equivalent training for GCP in behavioral clinical trials was vital. The Social and Behavioral Work Group was formed with the primary purpose of ensuring that a core set of competencies and training in GCP would be relevant to behavioral trials. The work group was composed of 25 members including an administrative and faculty lead (online Supplementary Material). The members represented many CTSA-funded hubs nationwide and included both study investigators and coordinators who had experience in behavioral trials. The primary mode of interaction of this work group was through biweekly conference calls. A central web storage site was used to share materials. The group co-leads reported, advised, and determined strategic direction from the ECRPTQ leadership through direct participation on the project steering committee.

Preliminary Discussions and Consensus Building

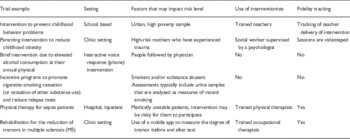

After the Social and Behavioral Work Group was formed, it was first necessary to orient the group to the NIH’s revised definition of clinical trials and to discuss how the definition related to behavioral interventions. Some group members had not conceptualized their intervention studies as clinical trials, and there was a need to operationalize what was considered a “behavioral” intervention. The group members and leads provided examples from their own work as well as relevant materials from the literature which were uploaded onto a central web storage site. Consequently, the group discussed various types of interventions that could be defined as behavioral in nature and tested through clinical trials. This discussion was important for the group to begin thinking about key differences between design and conduct of behavioral clinical trials compared with drug, device, or biologic trials. Examples of behavioral trials discussed are provided in Table 1. Differences between behavioral trials compared with drug and device trials included variety of research settings (such as clinics, schools, home), the tendency of these trials to be of lower risk to participants, and the increased complexity of these trials through the use of people who provide interventions (referred to as interventionists) and the fidelity tracking necessary to ensure integrity of the delivery and receipt of the intervention.

Table 1 Examples of behavioral clinical trials

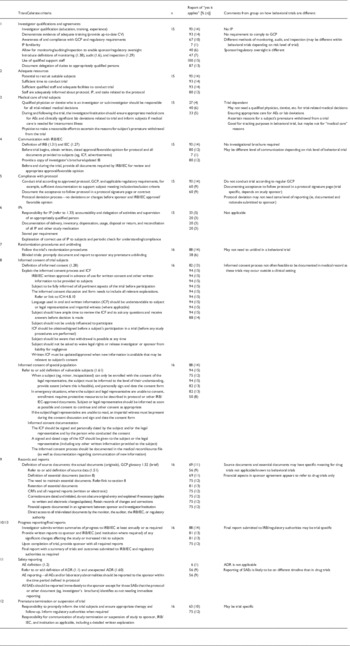

Once the group came to consensus regarding what was considered a behavioral clinical trial, they were oriented to the concept of GCP. The term GCP was not familiar to many members in the work group as most social and behavioral researchers do not undergo this training unless they are involved in a drug or device clinical trial. Relevant materials about GCP, its origins, and rationale for training were uploaded to the central web storage site for members to read and discuss on initial conference calls. The group reviewed the Minimum Criteria for GCP training of investigators and site personnel from TransCelerate BioPharma (based upon the document from the International Committee on Harmonization [ICH]) [3] and its criteria for relevancy to behavioral trials are listed in Table 2. This was done by sending an electronic survey to group members and asking them if they felt that each criterion was relevant, maybe relevant, or not relevant to behavioral clinical trials. The survey responses were tabulated and discussed in the group.

Table 2 TransCelerate criteria: results of survey and group discussion regarding behavioral trial differences

GCP, Good Clinical Practice; IP, investigational product; AE, adverse event; ICF, informed consent form; SAE, serious adverse event; ADR, adverse drug reaction.

Building on these foundational activities, the group was asked to review existing training for GCP and to identify gaps specific to behavioral research. Pairs of reviewers were assigned to submit a written review of each of the programs. Individually they accessed the training and completed the course. Reviewers were asked to evaluate the effectiveness of the content for best practices training for social and behavioral researchers. They also reviewed the courses for design features and were asked to describe what they liked and did not like about the experience of taking the course. During conference calls, reviews were discussed, compared, and synthesized. Pairs of group members were assigned different GCP training courses and their ratings were compared and discussed in conference calls.

Participation in Research Competency Adaptation for Social and Behavioral Trials

Representatives of the Social and Behavioral Work Group participated in the face-to-face meeting at the ECRPTQ conference in Dallas in February 2015 as described in the paper by Calvin-Naylor et al. [Reference Calvin-Naylor5]. These work group members helped to evaluate and refine research competencies that were part of a larger framework developed by the Joint Task Force for Clinical Trial Competency [Reference Sonstein4]. The work group offered recommendations which resulted in some adaptations to competencies shown in the appendix of that paper. The competencies served as a foundation for conceptualizing GCP training for social and behavioral researchers.

Results

Table 2 shows the results of the relevance of the GCP criteria to behavioral clinical trials. There were 15–16 responses for each criterion and the results were presented and discussed on a conference call with the group for clarity. The areas thought to be least relevant to behavioral trials included investigational products, medical care, safety reporting, and premature suspension of trials. Investigational products is an area clearly not relevant to behavioral trials, as having an investigational product would classify the trial as a drug, device, or biologic for regulation through the FDA. As behavioral trials typically pose minimal risks to participants and may not be conducted in a clinical setting, medical care of a qualified physician was considered to be only necessary in specific situations, such as behavioral trials with ill or medically unstable participants. This same line of reasoning applied to safety reporting as the reporting would be different for minimal risk trials. In addition, the group felt that unblinding or premature suspension of a trial would be a rare occurrence in behavioral trials.

Review of Existing GCP Training

Four commercial e-learning courses as well as one course through the NIH were reviewed. Across all courses reviewed, significant gaps in training were identified. The topics, with the exception of the focus on regulatory processes related to GCP, were felt to be largely relevant. However, the content was not specific to behavioral trials and lacked examples or scenarios that arise in social and behavioral research. In courses that were geared toward social and behavioral researchers, there was discussion about the breadth and depth of content presented. Most of the training was thought to be either too general or too specific for a best practices course. Some course content seemed redundant with basic training in human subject protections that investigators and coordinators need to take at their institutions when engaging in research. Other course content was deemed to be appropriate but highly specialized, such as modules about working with prisoners or international research studies. With regard to the user experience with each course, aspects that reviewers mentioned as promoting their engagement included high visual appeal, good narration, and interactive features. One course included job aids and reference links that were deemed especially useful. Although some reviewers felt that quizzes or knowledge checks throughout the course were engaging, others liked the ability to test out of a course altogether by taking a quiz separate from the course itself.

Discussion

The activities of the Social and Behavioral Work Group identified a clear need for specifying the construct of GCP for social and behavioral researchers. The term GCP was largely unfamiliar to the content experts and required group discussion and consensus building to relate GCP to the design and conduct social and behavioral research. After thorough review, it was determined that existing GCP training was not applicable for researchers conducting behavioral trials. Therefore, the Social and Behavioral Work Group recommended to ECRPTQ leadership that a new training program be created, focusing on the specific needs and unique research processes of social and behavioral research teams.

Best Practices Training in Social and Behavioral Research

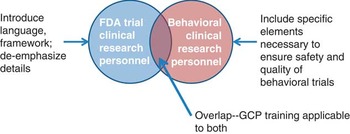

In order to develop appropriate training, it was necessary to better define the construct of GCP for social and behavioral researchers. Fig. 1 shows the conceptual model used. We felt that we should rename GCP to “best practices” as GCP in the traditional sense is not a term typically used in the context of social and behavioral research and has specific ties to regulation from FDA that is usually not applicable. Despite differences, there is an overlap in the competencies required for research personnel of FDA-regulated trials and behavioral trials. In order to create best practices training, it was necessary to address the overlap of what all research personnel need to know. Thus, the training requires an introduction to the context of GCP and definition of terms specific for behavioral research personnel. However, it is also important to de-emphasize areas not relevant to social and behavioral research. In addition, because behavioral trials often have additional complexity in design and implementation, specific content needed to be addressed, such as treatment fidelity. Content for best practices needed tailoring from GCP and needed to focus on specific job skills for both investigators and clinical research coordinators.

Fig. 1 Conceptual framework of how Good Clinical Practice (GCP) relates to behavioral clinical trials. FDA, Food and Drug Administration.

After receiving approval to move forward, a subset of volunteers from the Social and Behavioral Work Group were recruited to define content areas for a social and behavioral best practices training program. A mapping process was employed to identify potential topics and link them to competency domains defined by the ECRPTQ project. To do this, the work group team leads at the University of Michigan researched existing GCP and social and behavioral research training and provided information to the subgroup members. The Work Group leads reviewed several books on implementing GCP, examined educational materials on the principles of GCP from various sources, examined the results of the TransCelerate survey (shown in Table 2), and reviewed the current human subject training University of Michigan offers for social and behavioral research. Through a series of discussions via conference call, 8 topic areas were selected for inclusion as modules in a training program (see Table 3).

Table 3 Training modules for social and behavioral best practices course

GCP, Good Clinical Practice.

Content experts were identified for each training module topic. Working with an instructional designer, these experts defined learning objectives and outlined content for inclusion in the training modules. Learning objectives and content were thoroughly discussed by the entire work group and consensus was reached regarding the overall structure and learning objectives for a new social and behavioral training program. At this time, the course has been completed and available for download by interested institutions [6].

Conclusion

The goal of this project was to tailor competencies and the fundamental principles of GCP into what are deemed as best practices for social behavioral research and to translate those competencies into a framework for a series of e-learning modules. This project involved a high level of collaboration across CTSA hubs and codevelopment with benchmarking organizations such as The Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative that allowed for the opportunity to create a translational bridge between more traditional clinical trials and behavioral interventions. The training program is currently tailored to the specific needs and unique research processes of social and behavioral researchers and consequently will fill a critical training gap identified through the ECRPTQ process.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Research grant no. 3UL1TR000433-08S1 (Thomas Shanley, M.D.). The authors gratefully acknowledge the members of the Social and Behavioral Work Group as well as the numerous staff and faculty members from academic institutions nationally who graciously donated their time and expertise to this project.

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2016.3