The human race is challenged more than ever before to demonstrate our mastery, not over nature but of ourselves. Footnote 1

—Rachel Carson (Reference Carson1962)The issue in this case—and many others—is how best to limit the use of natural resources so as to ensure their long-term economic viability.

—Elinor Ostrom (Reference Ostrom1990, 1)[The Paris Accord’s] pledge-and-review system … transformed climate diplomacy from past gridlock by creating flexibility …[A] realistic crash program to cut emissions will blow through 2 degrees; 1.5 degrees is ridiculous. New goals are needed.

—David Victor (Reference Victor2015, 1)A growing chorus of political scientists operating from multiple subdisciplines has called for greater attention to problem-relevant research in general (Isaac Reference Isaac2015; Shapiro Reference Shapiro2007), and the catastrophic environmental crises of climate change and mass species extinctions in particular (Green Reference Green2018; Skocpol Reference Skocpol2013; Neville and Hoffmann Reference Neville, Hoffmann, Dauvergne and Alger2018). In this journal alone, Javeline (Reference Javeline2014) has lamented inattention to climate adaptation challenges facing humans, while Falkner (Reference Falkner2016) calls for the design of “minilateral” “climate clubs” to reduce “free-riding” under the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. Economists have made similar appeals (Sachs et al. Reference Sachs, Stiglitz, Mazzucato, Brown, Dutta-Gupta, Reich and Zucman2020; Nordhaus Reference Nordhaus1991).

We offer the opposite conclusion: that political science has profoundly influenced the development of adjudicating frameworks across the social sciences about how to best address environmental problems. Specifically, we argue that the ideas and approach championed by former APSA president Elinor Ostrom in Governing the Commons (1990; hereafter GTC) reinforced and accelerated two trends: turning to the discipline of economics to champion deductive and generalizable theories about politics, policies, and institutions (Shapiro and Green Reference Shapiro and Green1994; Simon Reference Simon1955; Elster Reference Elster1986); and careful interrogation of a clearly specified sustainability challenge—in Ostrom’s case a particular type of “collective action” dilemma known metaphorically as the “tragedy of the commons”—in order to inform and justify inductively generated policy and institutional analysis (Green and Shapiro Reference Green and Shapiro1995). Fresh insights from these somewhat paradoxical approaches were instrumental in Ostrom winning the Nobel prize in economics.

We argue that GTC’s most important contribution to sustainability studies was the way it demonstrated how careful attention to a particular kind of problem can yield innovative solutions. However, its greatest impact was to reinforce the quest for universal analytical frameworks to adjudicate any type of sustainability challenge. This bias occurred directly by those championing economic utility maximization as the overarching goal of policy analysis rather than, as most scholars had assumed in the 1960s and 1970s, as the primary cause of ecological degradation (Meadows et al. Reference Meadows, Meadows, Randers and Behrens1972). It also occurred indirectly, by those who turned instead to rich literatures in political science on deliberative governance to offer competing universalist approaches also disconnected from problem structure. As a result, today’s sustainability-focused political scientists overwhelmingly engage in analysis that shifts attention from understanding how domestic and global environmental policy innovations and institutions might emerge and be designed to avert the negative impacts of humans on the environment (Paehlke Reference Paehlke1989; Speth Reference Speth2004) to assessing whether, given human material interests, it is economically “rational” or feasible to do so. Those political scientists who maintain a focus on problem structure overwhelmingly reinforce GTC’s economic utility enhancing concerns, which are the mirror opposite of environmental tragedies.

The implications of our review are profound. Political scientists’ quest to explain the limited effectiveness of today’s environmental policies that turn to the relative influence of powerful corporations, environmental groups, and marginalized communities, or broader institutional and historical factors that shape class, inequality, and distributional outcomes, need to expand to assess the role of the discipline itself: that is, whether our frameworks and sub-disciplinary debates have, through reinforcing certain metaphors over others, championed conceptions of sustainability that have contributed towards the acceleration of environmental decline. Ironically, Ostrom herself expressed concern about these influences: “[m]any policy prescriptions are themselves no more than metaphors” that “can be harmful,” producing outcomes “substantially different from those presumed to be likely” (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990, 22-23).

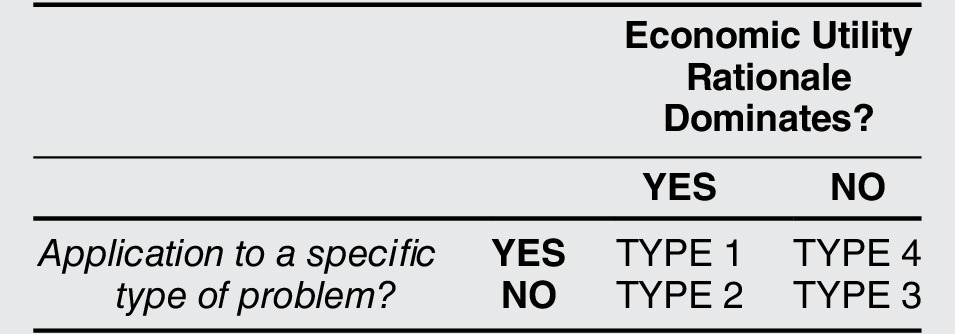

We elaborate our argument in the following analytical steps. First, we identify four “ideal types” of problems based on their consistency or inconsistency with GTC’s emphasis on problem structure and economic utility. Second, we identify and review how four leading schools of sustainability reinforce each type. Third, we show how each school’s moral foundations produce distinct “prescriptive projects” that require, for instrumental reasons, expertise in different kinds of research methods and analytical skills. Fourth, we review the contribution of these schools to assess a startling trend: the drift away from treating climate and mass species extinction crises as Type 4 problems. We conclude by offering suggestions for how political science might bring the environment back in.

Four Problem Types and Four Reinforcing Schools

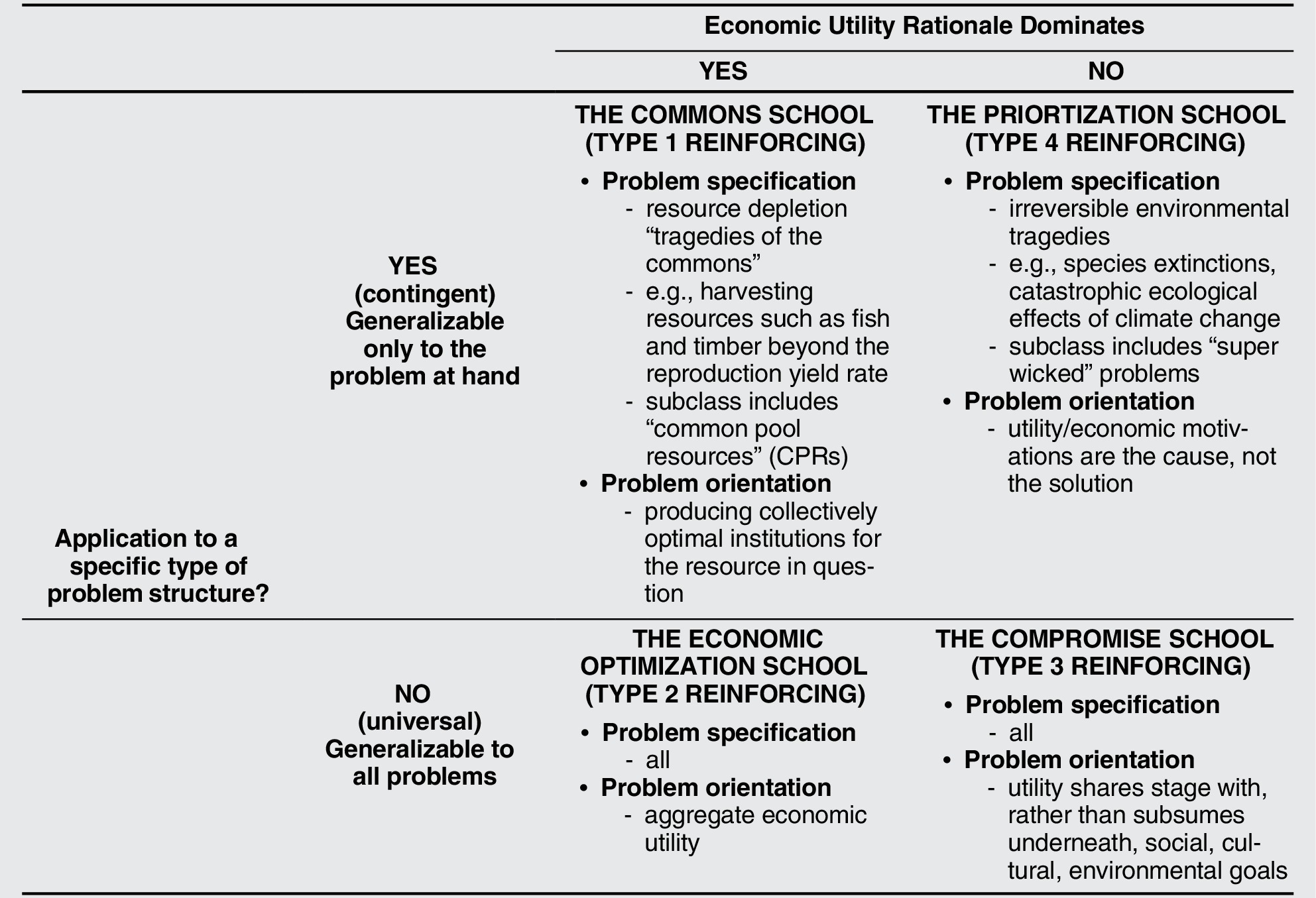

Types 1 and 2 correspond to GTC’s emphasis on economic utility while Types 1 and 4 embrace GTC’s careful attention to problem structure (Table 1). Types 2 and 3 champion universal frameworks to adjudicate any challenge. Each of the four sustainability schools’ moral underpinnings bias each type in two distinct, but related, ways: how they conceive of sustainability challenges, and, as a result, the empirical data and evidence they target.Footnote 2 These biases are reinforced by very different ways to treat “whack-a-mole”Footnote 3 effects: that is, those cases in which solving one problem makes another worse. The commons, economic optimization, and compromise schools narrow consideration of policy options for ameliorating Type 4 environmental problems to those that are synergistic with Type 1, 2, or 3, which are biased toward human material interests.

Table 1 The four faces of sustainability

The Commons School (Type 1 Reinforcing)

The commons school derives its moral foundations and theoretical roots from concerns about how to understand and resolve “collective action” dilemmas (Olson Reference Olson1965) in which, owing to absent or weak governance institutions, individuals make “rational” decisions to engage in behaviours that produce suboptimal outcomes (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990, 3). In the classic “prisoner’s dilemma” metaphorical example, a thief interrogated in a different cell and unable to coordinate and create compliance mechanisms with an accomplice will make the utility chasing “rational” choice to confess (Nash Reference Nash1953) because this avoids the risk of an expected higher prison term from remaining silent if the accomplice confessed—even though the thief is aware that that collective silence would have produced lower aggregate prison terms.

The commons school has applied the collective action metaphor in sustainability studies most notably to analyses designed to avoid, or ameliorate, “tragedies of the commons” (Hardin Reference Hardin1968) in which “open access” situations lead to depletion of “subtractable” resources: that is, when an individual’s use of a specific good reduces the ability of someone else to use it. This school holds that in the absence of coordinating institutions it is entirely “rational” for individuals to participate in overharvesting to realize short-term economic benefits, because, in the absence of collective controls, long-term resource collapse is inevitable. This school’s moral duty to avert commons tragedies, including their devastating effects on local communities, was behind Ostrom’s exhortation in her presidential address to the American Political Science Association that developing a well-articulated theory of collective action ought to be “the central subject of political science” (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1998, 1).

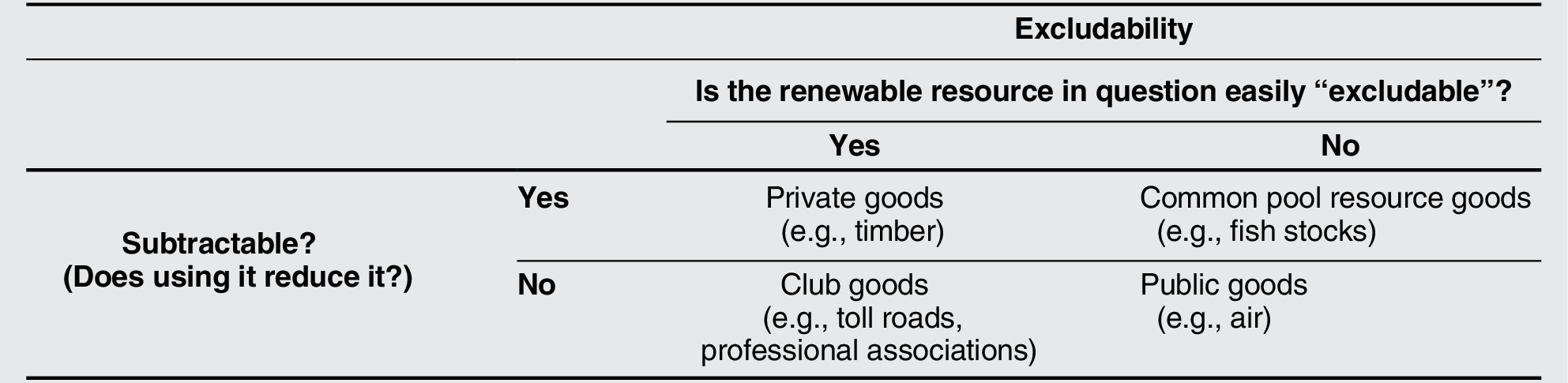

GTC’s contribution to these questions was, through careful attention to the problem structure of commons challenges, the conceptual and empirical discovery that—for either biophysical reasons (such as the ability of fish to swim long distances) or traditional community practices—excluding access was not a viable solution (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990, 183). This distinction created two ways to classify subtractable resource challenges: excludable “private goods” that characterized most analyses of commons tragedies until GTC and non-excludable “common pool resources” (CPR) on which GTC focused attention. These distinctions also led to utility reinforcing conceptions of “non-subtractable resources” as either excludable “club goods” or non-excludable “public goods” (table 2).

Table 2 GTC’s contribution to Type 1 Tragedy of Commons conception of resource goods: Non-excludable common pool resources

Note: Examples of goods in each cell are illustrative. Commons and sustainability scholars continue to differ on whether to treat trees, fish, and ecosystems as “private goods,” “common pool resources,” and, in some cases, as “public” or “club” goods. These debates can be traced back, in part, to different ways in which categories and corresponding solutions are constructed (Young 2007, 3-4). For example, following GTC, some view institutions, depending on their design, as causing or solving a particular resource depletion tragedy (i.e., they constitute the “independent” variable). However, others view institutional arrangements, not simply biophysical features, as playing a role in making excludability difficult (i.e., they constitute part of the “dependent” variable). It follows that if a researcher deems institutions to have played a role in making excludability difficult, it is equally plausible, in contrast to GTC’s inferences, to consider designing institutional innovations to make exclusion possible. This ambivalence in treating excludability as fixed and hence a “common pool resource”, or as changeable, and hence a “private good,” is reflected in GTC’s conclusions that resource quotas that exclude access are useful for managing, rather than converting, CPRs.

Source: Adapted from V. and E. Ostrom Reference Ostrom, Ostrom, Hardin and Baden1972 and Gibson, Mckean, and Ostrom Reference Gibson, McKean and Ostrom2000.

Ostrom was clear in her beliefs that the tool of privatization, rather than coercive state control, was the most optimal for managing “strictly” private goods (Ostrom Reference Ostrom2003, 259; Gibson, McKean, and Ostrom Reference Gibson, McKean and Ostrom2000, 7). GTC’s concern was that applying privatization as a solution to non-excludable CPR tragedies could produce even more tragic outcomes than if nothing had been done at all (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990, 13-14) such as the expropriation of communal forests that had historically avoided resource collapse (Bartley et al. Reference Bartley, Andersson, Jagger and Van Laerhoven2008; Gibson, McKean, and Ostrom Reference Gibson, McKean and Ostrom2000). Instead, GTC posited that local communal governance institutions, including “groups of individuals,” rather than “distant” central authorities, were best poised to avoid or reverse many types of unsustainable CPR practices (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990, 21-23, 60-61, 183-185). Somewhat ironically, similar inductive reasoning led the commons school, guided by the “polycentric” metaphor, to advocate for the “scaling up” of its rationalist design principles to ameliorate (economically sub-optimal) “global commons” resource challenges that cut across multiple jurisdictions.

Whack-a-mole. Since GTC’s publication, commons school scholars are keenly aware of the need to avoid internal “whack-a-mole” effects that can occur when treating all commons tragedies as excludable. Less attention has been placed on three external whack-a-mole effects that fall outside its moral, theoretical, and conceptual foundations. First, its emphasis on improving the sustainability of a specified resource, such as fish or timber, does not directly address whether the depletion of that good might lead to an economically more optimal outcome—such as forest land use clearing to promote lucrative mineral, extractive, manufacturing, real estate, or tourism activities. Second, while it pays attention to cultural practices that can foster collective long-term economic sustainability in the absence of formal institutions (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990, 149, 166; Sethi and Somanathan Reference Sethi and Somanathan1996), it did not formally incorporate into its model “suboptimal” historical cultural traditions that are degraded by an emphasis on economic utility (Buck Reference Buck, Conca, Alberty and Dabelko1998). Third, as we will detail, ecosystems are almost always degraded in some way by successful Type 1 solutions and institutions.

The Economic Optimization School (Type 2 Reinforcing)

Whereas the commons school champions economic utility to address a clearly specified collective action problem, the economic optimization school advances the moral belief, drawing on welfare economics, that the ability to solve any kind of problem is conditional upon finding policy solutions that enhance aggregate economic utility for society as a whole (Kenny Reference Kenny2011; Sen Reference Sen1979; Luke Reference Luke and Dahms2009).

Within sustainability studies, this school’s moral framework provides the rationale for most post-World War II development agencies, most notably the World Bank, and many specialized UN agencies, such as the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), as well as the creation of forestry, agriculture, and resource schools in Europe and North America that followed utilitarian principles to achieve “the greatest good for the greatest number in the long run” (Pinchot Reference Pinchot1987). It also underpins the field of environmental economics, which advances the causal belief that the rational and feasible way to address environmental challenges is to convert them into economic values (Stavins Reference Stavins1995; Sachs et al. Reference Sachs, Stiglitz, Mazzucato, Brown, Dutta-Gupta, Reich and Zucman2020; Thomas and Chindarkar Reference Thomas and Chindarkar2019). These moral frames, in turn, are reinforced through micro level metaphors including “externalities” that treats environmental degradation as economically suboptimal and “payment for ecosystem services” by those who believe that valuing nature economically will provide ancillary environmental benefits (Sell et al. Reference Sell, Koellner, Weber, Proctor, Pedroni and Scholz2007). This morality is also behind the “polluter pays” metaphor (OECD 1972) which holds that firms can choose to make economic payments to offset, rather than stop, environmentally degrading behaviour.

This school also includes neo-utilitarian international relations sustainability scholarship on cooperation and rational institutional design (e.g., Keohane and Victor Reference Keohane and Victor2016; Ovodenko and Keohane Reference Ovodenko and Keohane2012) whose analytical frameworks do not directly incorporate, nor are they derived from, the structural features of the environmental problem at hand, but on efficient institutions and utility enhancement. Scholars from this community created the “Oslo-Potsdam” approach to environmental effectiveness, which measures policy options against their “collectively optimal” utility enhancing human benefits (Hovi, Sprinz, and Underdal Reference Hovi, Sprinz and Underdal2003). For these reasons its application can result in an international regime being assessed as “effective” even when the ecological problem at hand continues to worsen (Kütting Reference Kütting2000; Young Reference Young2003a). In the most extreme cases, some treat Type 2 human satisfying outcomes not only as synergistic but as synonymous with Type 4 environmental concerns (e.g., Lomborg Reference Lomborg2001). Although GTC was initially justified based on a Type 1 problem conception, its rationalist project meant that the research program, and that of those who built upon it, were sympathetic to the economic optimization school’s moral philosophy (Ostrom Reference Ostrom2005).

Whack-a-mole. This school’s internal approach to whack-a-mole effects by assessing society-wide economic welfare-enhancing or -reducing impacts of a proposed policy option, leads them to and requires incorporating as many moles as possible—a process adherents refer to as “internalizing externalities.” However, this approach can create several external moles. At a broad level, its economic growth-biased policy solutions have played a role in fostering industrialization processes that have contributed to the homogenization of previously diverse local cultures while severely stressing the earth’s environmental “carrying capacity.” In addition, its emphasis on converting environmental values into economic utility comparators undermines reflexive considerations of a morality promoting the intrinsic value of ecological systems qua ecological systems.

The Compromise School (Type 3 Reinforcing)

The compromise school draws its moral foundations from a rich literature devoted to assessing how democracy, pluralism, legitimacy, trust, and authority might advance policymaking at multiple scales (Dahl Reference Dahl1961; Rosenbluth and Shapiro Reference Rosenbluth and Shapiro2018; Bodansky Reference Bodansky1999; Habermas Reference Habermas1973; March and Olsen Reference March and Olsen1998; Scharpf Reference Scharpf1999). Its adherents tend to be united around the promotion of “human dignity” rather than economic utility (Farr, Hacker, and Kazee Reference Farr, Hacker and Kazee2006).

Within sustainability studies, attention has been placed on assessing how inclusionary processes and deliberative spaces might foster meaningful involvement of disempowered environmental and social interests and values (Dryzek Reference Dryzek1990; Hoberg Reference Hoberg1992; Pinkerton Reference Pinkerton1993; Aklin and Mildenberger Reference Aklin and Mildenberger2017). Its moral philosophy is reinforced by significant evidence that, if well designed, the participatory processes can enhance legitimacy, trust, and authority to meaningfully affect policy outcomes (Barry and Eckersley Reference Barry and Eckersley2005).

This school has been prominent at the international level since the 1987 Brundtland Commission (WCED 1987), which famously called for “meeting the needs of the current generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” In doing so, it directly confronted the economic optimization school’s belief that future economic impacts ought to be discounted and that social and environmental outcomes could be assessed on their economic values. It also engaged a conversation with the prioritization school by incorporating concerns about the impacts of humans on the natural environment (Wang Reference Wang2004).

Whack-a-mole. The internal approach to moles of balancing economic, environmental and social goals, risks several external moles. First, stakeholder engagement at domestic and global levels often produce “incremental” approaches that rarely veer far from the status quo, in part owing to the role of powerful economic interests (Coglianese Reference Coglianese1997). Mitchell and Carpenter (Reference Mitchell and Carpenter2019, 5) found, for example, that C02-emitting business interests have acted as “veto-players” in international climate deliberations when they deem “the costs of climate action as excessive.” Second, the application of deliberative governance principles can result in disastrous consequences for the problem at hand. For example, Type 3 multistakeholder engagement in the Newfoundland cod fishery resulted in a compromise decision to allow harvesting at levels higher than what scientists found were required for species to reproduce (Berrill Reference Berrill1997). The result was that the Type 1 fisheries economy collapsed, further degrading the Type 4 marine ecology from what commercial fishing had already caused.

The Prioritization School (Type 4 Reinforcing)

The prioritization school advances a moral philosophy in which analysts must distinguish, and give priority to, “first order” principles and problems (see, for example, Rawls Reference Rawls1971). The classic example concerns the eradication of slavery in which the very application of economic optimization or compromise approaches that turn attention to assessing whether or to what extent slavery might be allowed undermines the problem conception and outcome itself: that is, that no one, for any reason, ought to be allowed to own another human being. This school incorporates three central analytical tasks: overcoming Types 2 and 3 and “commensurability biases” to rank or prioritize problems; developing—just like GTC—inductively generated solutions based on the key features of the problem at hand; and engaging in lexical or sequential policy analysis in which addressing lower-ranked problems are limited to solutions that do not undermine higher-ranked problems.

Within sustainability studies, the prioritization school targets attention to the attributes of key social and environmental problems that usually result from, or are exacerbated by, those very policies that embrace Types 3, 2, and 1 conceptions (Sinden, Kysar, and Driesen Reference Sinden, Kysar and Driesen2009; Zeckhauser and Schaefer Reference Zeckhauser, Schaefer, Bauer and Gergen1968; Ackerman and Heinzerling Reference Ackerman and Heinzerling2004; Taylor Reference Taylor1992; Meadows et al. Reference Meadows, Meadows, Randers and Behrens1972). This school’s heyday was during the “first wave of environmentalism” in the 1960s and 1970s that was sparked, in part, by Rachel Carson’s (Reference Carson1962) warning that “[T]he human race is challenged more than ever before to demonstrate our mastery, not over nature but of ourselves.” Tribe (Reference Tribe1972, 95) famously reinforced this ethical frame by arguing- in direct confrontation with the economic optimization school’s morality—that “[it does not] seem peculiar to insist … that a lower limit be established on especially cruel treatment of animals, whatever the economic gains this cruelty brings to persons in general” (Tribe Reference Tribe1972, 96). Tribe argued that leading contenders for Type 4 status included “vulnerable or ‘fragile’” problems, especially “ecological balance, unspoiled wilderness, species diversity, and the like … [that are] … intrinsically incommensurable, in at least some of their salient dimensions, with the human satisfactions” (Tribe Reference Tribe1972, 96).

Just like the slavery case, the prioritization school’s approach is usually required to achieve “fit for purpose” environmental solutions (Tribe Reference Tribe1972, 95, 96, 99). This is because failure to grant the climate and species extinction crises as Type 4 challenges risks adopting policy and institutional solutions that are inconsistent with, or gloss over, ecological knowledge: that is, producing Newfoundland-esque outcomes for the world’s most important ecological challenges (IPCC 2018; IPBES 2019).

Whack-a-mole. The prioritization school recognizes that its sequentialist morality can create “collateral damage” moles. Its ranking of environmental problems as highest on the pecking order has been criticized as “elitist” (Farrell Reference Farrell2020) that ignores the plight of the world’s most poor and vulnerable populations, including indigenous and rural communities. However, prioritization school scholars respond that granting lexical ordering to the environment can, indeed, subsequently ameliorate social and cultural challenges (Clapp and Dauvergne Reference Clapp and Dauvergne2005), just not in the way envisioned by economic optimization or compromise schools that in so many cases result in “lose/lose” undermining outcomes for ecosystems and local cultural traditions (McAfee Reference McAfee1999).

While proponents of the prioritization school within sustainability studies have thought carefully about how to handle external moles, the school has largely failed to explicitly assess the problem of internal moles: that is, how to conceive of and research the range of Type 4 environmental problems with which to grant lexical status. Intriguingly, Ostrom called for such thinking, arguing that while biological and ecological systems were different from those covered in GTC, they, too, could be enhanced by similar inductive attention to the features of the problem at hand (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990, 25-26).

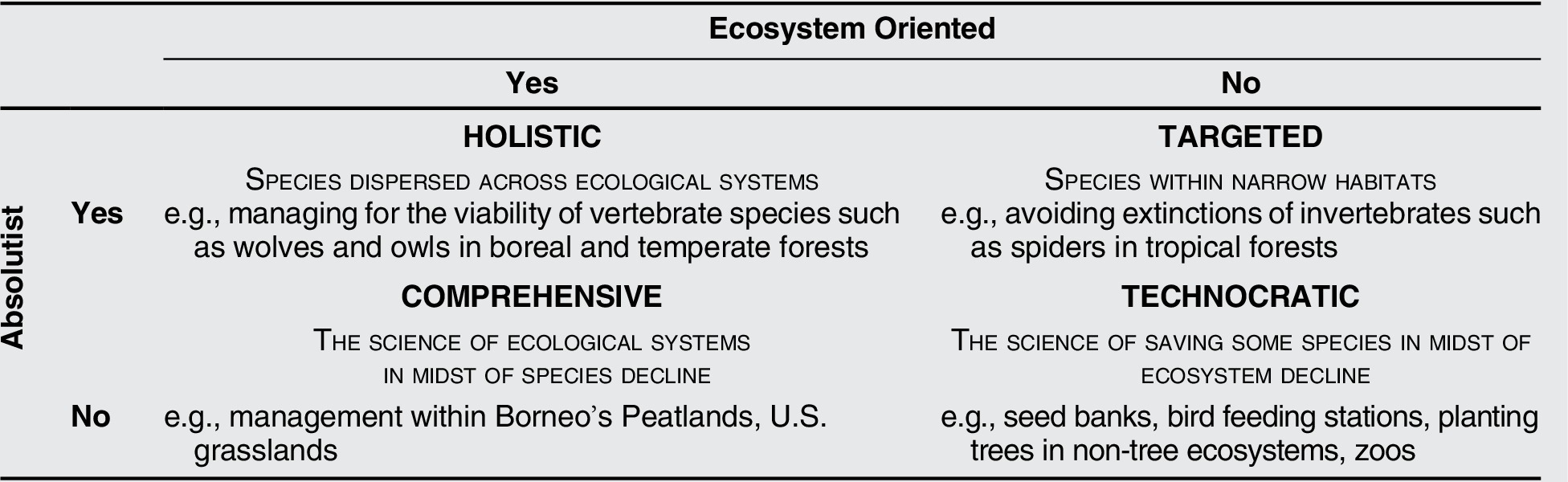

Attention to this task reveals four implicit approaches to prioritizing environmental challenges (table 3). The holistic approach is motivated by scientific evidence that, in some cases, the structure and function of an entire ecosystem is required to maintain the viability of an individual species. The end point for lexical ordering means that both the species and eco-system must be granted first order status if each of them is to be effectively addressed. In these cases, data are collected to assess what amount of extractive activity, including eco-friendly logging practices, might be permitted without compromising either individual species or the broader ecological systems (Lindenmayer and Franklin Reference Lindenmayer and Franklin2003). Intriguingly, GTC appeared to favour this approach when advocating for the identification of relevant proxy species with which to guide inductive policy and institutional solutions for advancing ecosystem sustainability (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990, 25-26). In contrast, the targeted approach draws on scientific evidence—especially but not exclusively from tropical and subtropical climates—that some species, including non-charismatic invertebrates, live on such small parcels of land that any act of extraction will almost certainly result in their extinction (Grove Reference Grove2002; Wijedasa et al. Reference Wijedasa, Jauhiainen, Könönen, Lampela, Vasander, Leblanc and Evers2017; Nair Reference Nair2007).

Table 3 Four approaches to the tragedy of Type 4 species extinctions

The comprehensive approach targets maintaining ecosystem structure and function in the face of some degree of “inevitable” species loss given human disruptive practices. The overarching concern is to identify the “limits” or “carrying capacity” of natural systems. This approach is behind the Paris Accord’s 1.5°C goal—which, drawing in the IPCC’s scientific review, explicitly accepts some degree of ecological degradation caused by greenhouse gases, but at a level that is expected to avoid catastrophic changes in ecosystem structure and function.

The technocratic approach is motivated by the scientific evidence concerning species decline given inevitable ecosystem degradation. This approach has resulted in policy innovations from the creation of seed banks to store genetic material from degraded or destroyed ecosystems, the strategic placing of feeding sites for migratory birds, and even the creation of zoos and wildlife conservation areas. It also captures the motivations of those political and policy scientists who, working with engineers and businesses, focus attention on developing low-carbon technologies that are not derived based on, or are deemed unlikely to meet, the 1.5/2°C imperative.

These distinctions help qualify contradictory findings and arguments in sustainability studies and science. First, scholarly declarations of utility and environment synergies ignore or bypass empirical evidence from the targeted approach because any human-satisfying activity will result in extinction. Second, the holistic approach narrows consideration of synergies to those utility-enhancing activities that, following scientific evidence, are deemed not likely to threaten the viability of ecosystems and their species. Third, while the technocratic orientation has the most synergies across problem types, its acceptance of an ecologically degraded world is hardly the outcome that most Type 4 environmental sustainability scholars would find celebratory.

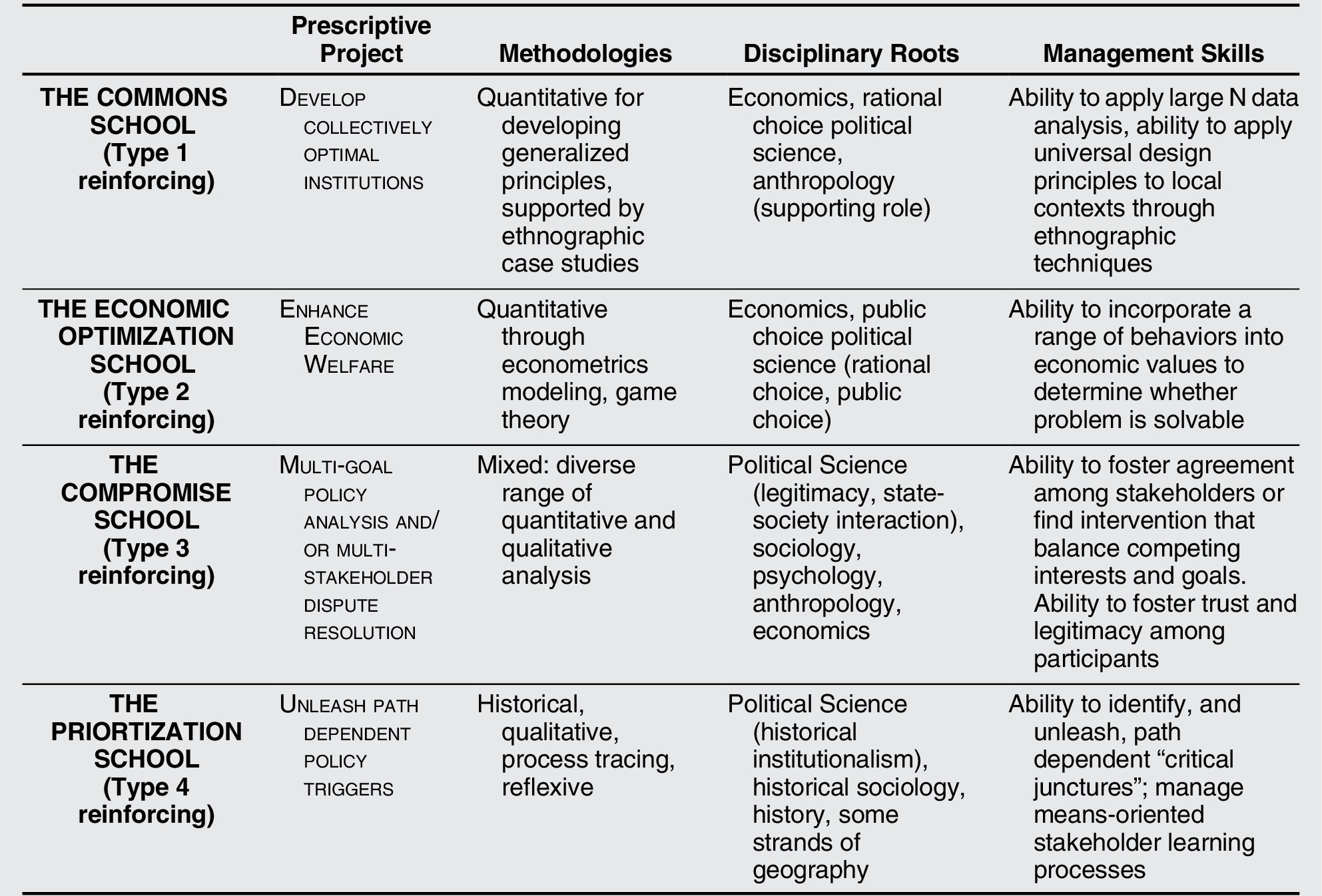

Table 4 Four sustainability schools

Four Prescriptive Projects

The moral and analytical foundations that shape each school’s adjudicating frameworks (Table 4) result in four prescriptive projects—successful implementation of which requires turning to and gaining expertise in distinct sub-disciplines and research methods (Table 5).

The Commons School

Design principles. GTC was clear that “better policies” (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990, 29) for averting or avoiding depleting water, fish, timber, and other goods that contribute to human food and resource production systems required “arranging for the supply of new institutions” (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990, 14) that must be placed on “how best to limit the use of natural resources so as to ensure their long-term economic viability” (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990, 1). Ostrom offered that getting the utility enhancing “institutions right” requires identifying and granting “user rights,” reducing “free-riding” risks, and “commitment problems.” She cautioned that successful efforts in “monitoring individual compliance with sets of rules” (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990, 27) would be “a difficult, time-consuming, conflict-invoking process” (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990, 14).

Methods. The search for theories to inform particular Type 1 challenges—in GTC’s case, CPR tragedies—helps explain the commons school’s embrace of game theoretic models and quantitative methods required to build them. Qualitative ethnographic methods play a supporting role in so far as their insights help improve model building (Brondizio, Ostrom, and Young Reference Brondizio, Ostrom and Young2009; Araral Reference Araral2014, 12; Andersson, Evans, and Richards Reference Andersson, Evans and Richards2009).

The Economic-Optimization School

Design principles. The dominant prescriptive project advocated by the economic optimization school is to engage in some type of “cost-benefit” analysis (Adler and Posner Reference Adler and Posner2009; Arrow et al. Reference Arrow, Cropper, Eads, Hahn, Lave, Noll and Portney1996) in which disparate social, environmental, cultural and economic goals are given comparable economic utility values. This approach, which underpins the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s policy to value each statistical human life at $9.47 million USD (Environmental Protection Agency 2020) involves modelling across a range of outcomes, as well as discounting future economic impacts, to identify the “best” or most “rational” policy options. Internal debates—including whether policies must be avoided that increase inequality (Kaldor Reference Kaldor1939) whether operationalized as widening gaps in relative gains (Piketty Reference Piketty2015) or Pareto losses (Awan Reference Awan2013)—reinforce the school’s overarching emphasis on utility enhancing orientations by narrowing measurements of inequality to economic outcomes.

Methods. The economic optimization school requires application of quantitative and modelling techniques, including agent-based modelling and econometrics, to project future outcomes, and the production of quantitative surveys of consumers and the public’s “willingness to pay” so that concerns about species extinctions, wilderness, and the catastrophic ecological effects of climate change can be converted into economic values (Turner et al. Reference Turner, Paavola, Cooper, Farber, Jessamy and Georgiou2003).

The Compromise School

Design principles. The compromise school’s prescriptive project turns to applying some type of “multi-goal” policy analysis (Weimer and Vining Reference Weimer and Vining1992) and stakeholder deliberations to achieve consensus or “dispute resolution.” They specifically incorporate research on the ways in which different interests or values might be incorporated to avoid Type 2 drift (Raymond and DeNardis Reference Raymond and DeNardis2015; Clémençon Reference Clémençon2012).

Methods. Decisions over methods turn to “multi-disciplinary” or “interdisciplinary” knowledge generation owing to causal and moral beliefs that integrating a diversity of perspectives will yield the most legitimate and effective policy responses (Nilsson and Weitz Reference Nilsson and Weitz2019; Saez and Requena Reference Saez and Requena2007; Clark and Wallace Reference Clark and Wallace2011). Special attention has been placed on applying comparative qualitative case studies, reinforced by quantitative methods, to understand how environment and development “advocacy coalitions” might reach policy consensus (Sabatier Reference Sabatier1988).

The Prioritization School

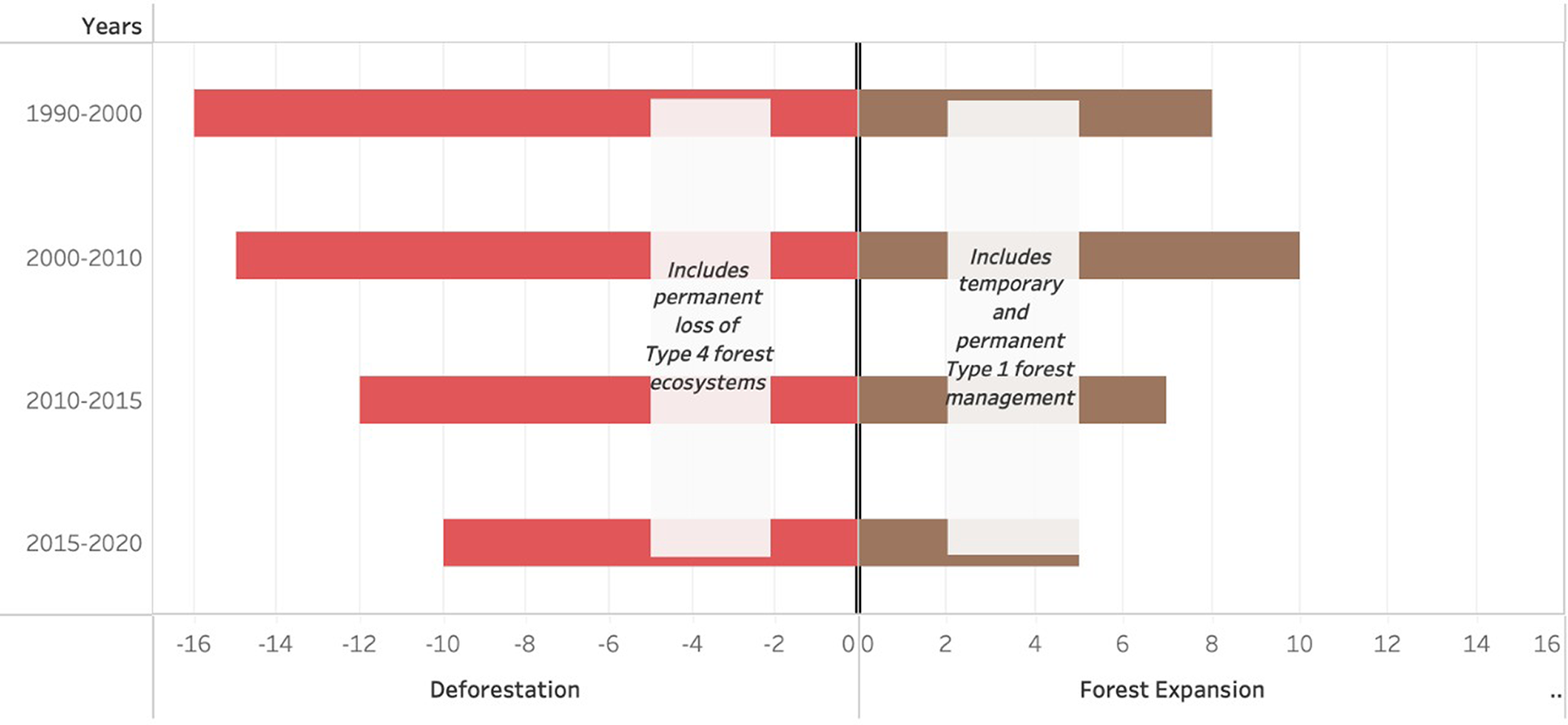

Design principles. The prioritization school is motivated by data produced from the biological, natural, and physical sciences about the startling decline of species and ecosystems (Kütting Reference Kütting2000). It places careful attention on what scientific evidence indicates is required to avoid or reverse the effects of human activity in general, and commodification of nature in particular, on terrestrial, marine, and atmospheric ecological systems. This task requires, for example, understanding and disentangling scientific evidence about the shorter “shelf life” of land use-caused climate change emissions that also threatens biodiversity from longer-term emissions caused by carbon-dependent industrialization processes. Members of this school are keenly aware of the need to avoid conflating environmental and economic outcomes, such as measures of decreases and increases in “forest cover,” since the former often results from permanent decline of Type 4 primary forest ecosystems, while the latter includes temporary and permanent increases in Type 1 forest management (figure 1).

Figure 1 Global forest expansion and deforestation, 1990-2020 (million hectares per year)

Source: FAO stat

Methods. Prioritization scholars recognize that Type 4 environmental problems such as the species extinctions and climate crises are overwhelmed in political and policy processes that emphasize Types 3, 2, and 1 short-term or material interests (Lockwood et al. Reference Lockwood, Kuzemko, Mitchell and Hoggett2017; Levin et al. Reference Levin, Cashore, Bernstein and Auld2012). They therefore devote much methodological attention to identifying “critical juncture” policy levers with which to create “path dependent” transformative pathways (Jordan and Moore Reference Jordan and Moore2020). In contrast to the economic optimization school’s negative view of path dependency as utility undermining (North Reference North1990), prioritization scholars assess how such processes can, and do, change policy outcomes, values, and feasibility calculations (Lockwood et al. Reference Lockwood, Kuzemko, Mitchell and Hoggett2017; Pierson Reference Pierson1993).

This school recognizes that critical junctures are not only triggered by societal and stakeholder conflict (Skocpol Reference Skocpol2013)Footnote 4 but through the creation of innovative “policy mixes” (Howlett Reference Howlett2019). The latter turns analytic attention not only to the goals and tools of policy, but to the causal impact of choices over calibrations that dictate resources and approaches to compliance, and policy settings that specify behavioural requirements (Hall Reference Hall1993). This approach was integral to the multi-faceted design of Germany’s successful and widely diffused “feed-in-tariffs” policy aimed at accelerating uptake of low carbon energy sources (Meckling Reference Meckling2019). Its unfolding effects over a decade and a half not only reduced the price of solar panels owing to increasing economies of scale, but also caused changes to behavioural norms and beliefs that dramatically altered political feasibility and willingness to pay calculations (Schmid, Sewerin, and Schmidt Reference Schmid, Sewerin and Schmidt2019).

For these reasons, the prioritization school places a premium on developing and applying sophisticated qualitative methods necessary for producing reflexive thinking for deliberating over the thousands of policy design possibilities, as well as for choosing specific mixes based on their “plausible causal logics” for generating multiple-step trajectories capable of ameliorating the problem at hand. Specific techniques include “applied forward reasoning” (Bernstein et al. Reference Bernstein, Lebow, Stein and Weber2000) and “process tracing” associated with historical institutionalist methodologies.

Table 5 The four sustainability school’s prescriptive projects: Methodological, disciplinary, and training biases

Drifting Away from Type 4: Political Science’s Contribution to Sustainability Studies

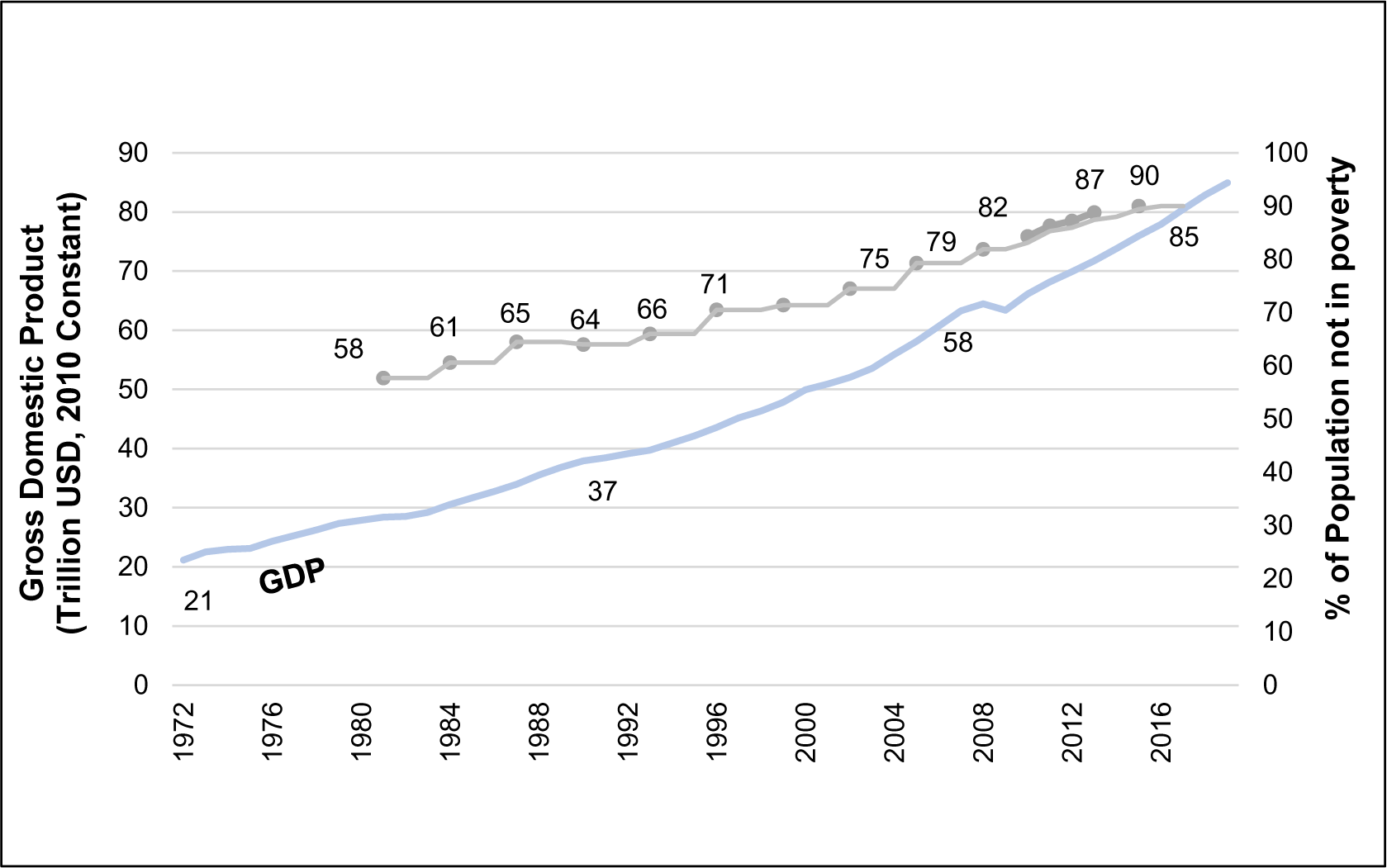

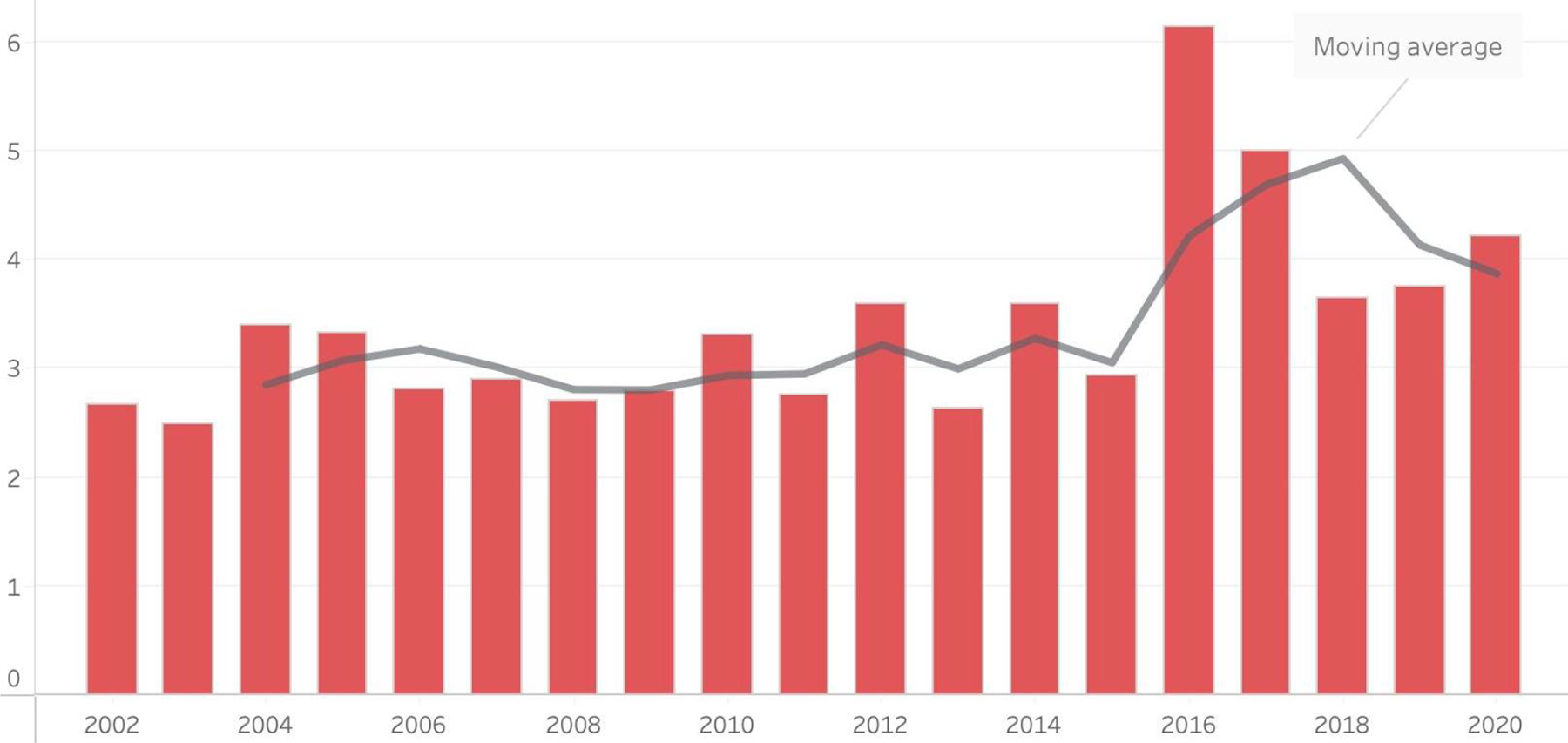

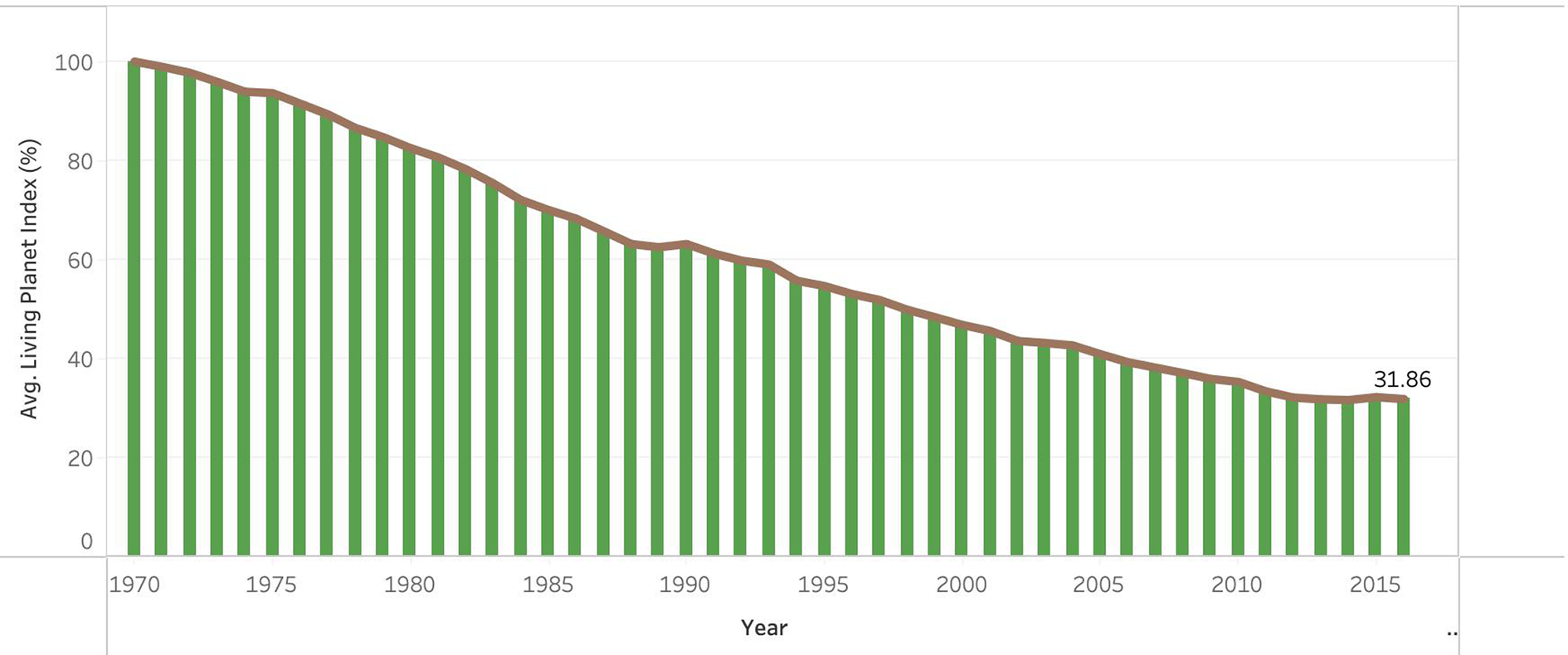

There is widespread recognition that the economic optimization school has helped advance the design of Type 2 development policies around the world, and that these have contributed to exponential economic growth since the 1970s that has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty (figure 2). There are also widespread concerns among all four schools about several unintended whack-a-mole effects including increases in greenhouse gases (figure 3), the decline of ecological systems exemplified by loss of tropical primary forests (figure 4) and the resulting decline in species abundance (figure 5) (McCauley Reference McCauley2006). While political science has provided several foundational approaches that turn to global social structures and mechanisms of class reproduction that influence societal and government conceptions of problems (Lukes Reference Lukes1974; Herman and Chomsky Reference Herman and Chomsky1988; Lindblom Reference Lindblom1977; Wendt Reference Wendt1987; Bachrach and Baratz Reference Bachrach and Baratz1962), less attention has been placed on our own culpability in causing these moles.

Figure 5 Species abundance (1970s baseline)

Source: Living Planet Index 2016; Our World in Data 2020

Domestic Policy Responses to Species Extinction Threats

Type 4. A generation ago the prioritization school played a central role in researching and drawing conclusions about the conditions through which environmental tragedies might be averted. Its contribution to Type 4 species extinction threats resulted in several explanatory and applied conclusions—almost all of which confront GTC’s design principles for CPR challenges. First, transnational political economy scholars found that economic interests promoted conceptions of sustainability that narrowed approaches to conservation to those consistent with economic optimization (Dauvergne Reference Dauvergne2001; Gale Reference Gale1998; Levy and Egan Reference Levy and Egan1998; Curran and Trigg Reference Curran and Trigg2006) and sought to incorporate concerns about the economic prosperity of forest- and resource-dependent communities into their Type 1 and 2 projects, even if doing so resulted in increasing extinction threats (Voigt et al. Reference Voigt, Wich, Ancrenaz, Wells, Wilson and Kuhl2018).

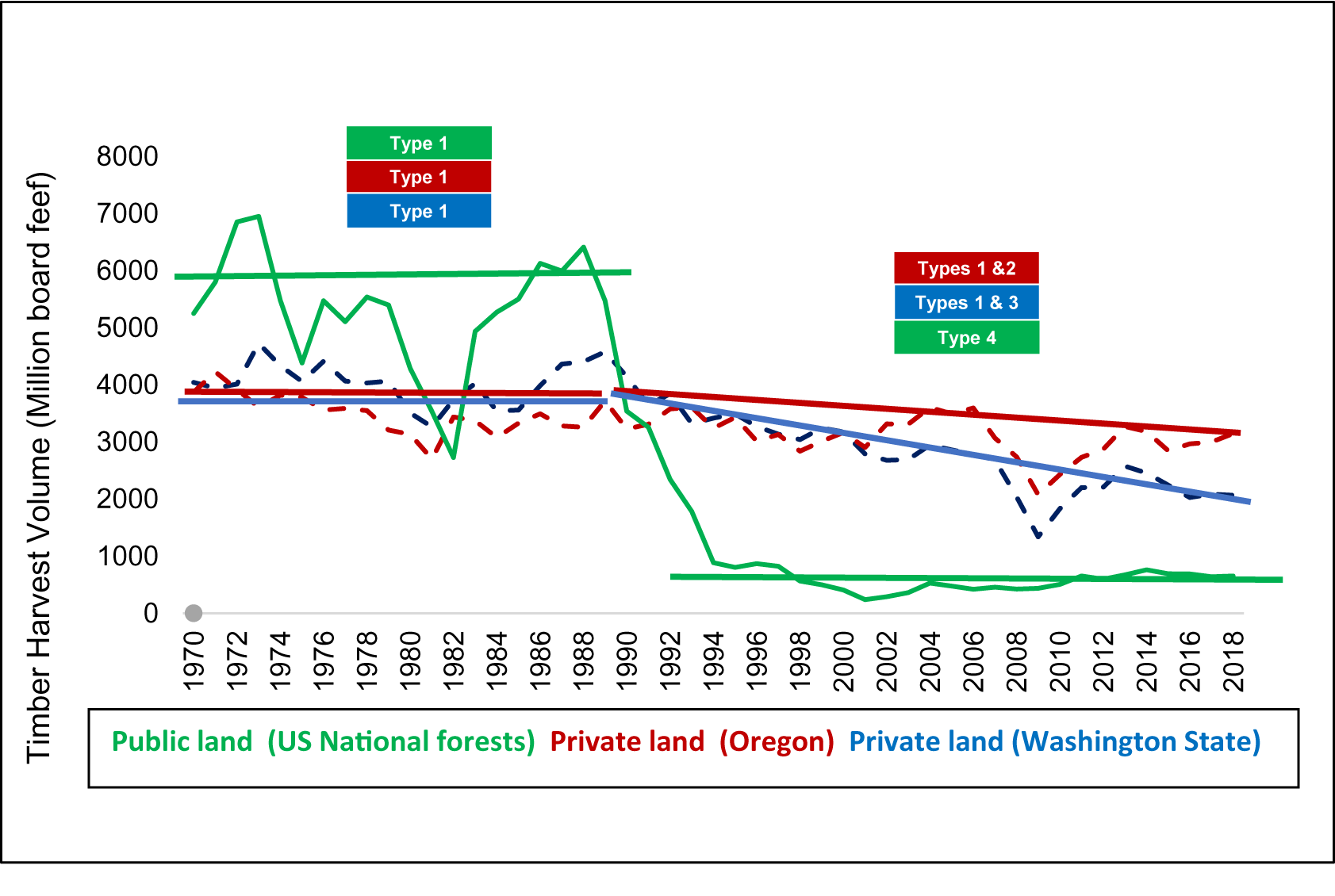

Second, specific wording of policy objectives, settings, and calibrations can create path-dependent Type 4 critical junctures. For example, political science research found that the conservation of old growth forests and restriction of logging practices in the U.S. Pacific Northwest was owing to the requirement that a lead agency develop a management plan to maintain the “viability” of a species listed as threatened or endangered (Cashore and Howlett Reference Cashore and Howlett2007). In this case, massive shifts toward Type 4 holistic ecosystem management (table 3) and away from Type 1 logging practices on national forest lands (figure 6) followed scientific evidence that the “Northern Spotted Owl” required old growth forests to survive (Kohm Reference Kohm1991; Franklin Reference Franklin1994; Spies et al. Reference Spies, Stine, Gravenmier, Long and Reilly2018).

Figure 6 Effects of Dominant Problem Types on Logging in the U.S. Pacific Northwest, 1970–2018

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station 2020

Third—and in contrast to the commons school’s emphasis on decentralization and “subsidiarity” (e.g., Wright et al. Reference Wright, Andersson, Gibson and Evans2016; Somanathan, Prabhakar, and Mehta Reference Somanathan, Prabhakar and Mehta2009)—national governments tend to give the most voice to environmental values, followed by state or provincial jurisdictions in federal systems, with the least voice within local governance systems denoted by strong economic dependence on resource extraction (Allin Reference Allin1982; Bishop, Phillips, and Warren Reference Bishop, Phillips and Warren1995; Leader-Williams, Harrison, and Green Reference Leader-Williams, Harrison and Green1990; Dunlap Reference Dunlap, Dunlap and Mertig1992).

Members of the prioritization school found that one reason for these trends is that citizens who live in urban areas are more likely to express higher levels of Type 4 environmental values (Czech and Krausman Reference Czech and Krausman1999; Inglehart Reference Inglehart1995), while rural and forest-dependent communities and commodity interests tended to view nature as providing utility enhancing benefits for humans (Paddle Reference Paddle2002; Laurance and Useche Reference Laurance and Useche2009) while holding negative views of endangered wild animals whose own foraging and predation undermine their Type 1 economic livelihoods (Vittersø, Kaltenborn, and Bjerke Reference Vittersø, Kaltenborn and Bjerke1998; Skogen Reference Skogen2015). The result is that environmental voices are often marginalized, or disempowered, when community governance initiatives are given the authority to manage specific resource challenges. These dynamics are illustrated in the case of the spotted owl, where president Bill Clinton successfully deployed vice president Al Gore to fend off the local congressional delegation efforts—strongly supported by forest-dependent communities—aimed at seeking relief from Type 4 statutory requirements (Yaffee Reference Yaffee1994; Sher and Stahl Reference Sher and Stahl1990; Gorte Reference Gorte1993; Lange Reference Lange1993).

Fourth, large scale national public land ownership—rather than privatization or local governance preferred by GTC—created the conditions through which lexical priority was granted to the owl (Giaari Reference Giaari1994). In contrast, logging on private land that applied Type 1, 2, or 3 conceptions, resulted in Newfoundland-esque responses that were inconsistent with the scientific evidence of owl conservation (figure 6).

Drift. What is critical for our analysis is that sustainability scholars wittingly and unwittingly played key roles in reinforcing the explicit project of powerful interests, including those from extractive industries, in fostering drift away from Type 4 conceptions dominant in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. In the owl case, the most immediate source of drift came from leading economic optimization school scholars who criticized ecosystem management as “irrational” because the decline in employment and incomes would cause significant Type 2 economic welfare reducing whack-a-mole effects (Lippke et al. Reference Lippke, Gilles, Lee and Sommers1990; Perez-Garcia Reference Perez-Garcia1993; Rawls and Laband Reference Rawls and Laband2004). These conclusions would be drawn on by several business interests who, worried that the owl case might set a precedent, funded Type 1 and 3 dialogues with environmental NGOs and forest-dependent communities (Forests Dialogue Reference Dialogue2018), and Type 2 “free market” resource and environment research think tanks strongly critical of (economic welfare reducing) environmental regulations (Simpson Reference Simpson2005).

A much more subtle but arguably even more powerful contribution to this drift came from compromise school scholars within the United States and globally who sought to understand better the “science” of conflict avoidance and consensus (see, for example, Halbert and Lee Reference Halbert and Lee1990; Wondolleck Reference Wondolleck and Susskind1988; Crowfoot and Wondolleck Reference Crowfoot and Wondolleck1991; Bacow and Wheeler Reference Bacow and Wheeler1984; Coglianese Reference Coglianese1997; Brach et al. Reference Brach, Field, Susskind and Tilleman2002; Koontz and Thomas Reference Koontz and Thomas2006). This conceptual turn would lead scholarly claims that their scientific research found that sustainability solutions required compromise be reached among disparate groups (Jacobsen and Linnell Reference Jacobsen and John2016; Bryant and Jackson Reference Bryant and Jackson1999; Baker et al. Reference Baker, Grove, Forster, Bonham and Bashford2009). Practitioners and policy officials would draw on these conclusions to justify as “scientific” their quest to elaborate the “foundations” (Starik Reference Starik1995) of “multiple-use” land management (Shands Reference Shands1988) that treat ecological systems as part of, rather than degraded by, human systems (Schmitz Reference Schmitz2018; Reed et al. Reference Reed, Barlow, Carmenta, van Vianen and Sunderland2019; Matson, Clark, and Andersson Reference Matson, Clark and Andersson2016). The U.S. National Academy of Sciences subsequently institutionalized this Type 3 drift by defining “sustainability science” as “the interactions between natural and social systems, and with how those interactions affect the challenge of sustainability: meeting the needs of present and future generations while substantially reducing poverty and conserving the planet’s life support systems” (Kates Reference Kates2011, 19449).

Global Environmental Climate Governance

Type 4. A generation ago the prioritization school was dominant within international relations (Markham Reference Markham1996; Najam and Sagar Reference Najam and Sagar1998). Its adherents documented the role of global capitalism and associated consumption in both causing these challenges (Meadows et al. Reference Meadows, Meadows, Randers and Behrens1972; Conca, Princen, and Maniates Reference Conca, Princen and Maniates2001) but also supporting Type 3, 2, and 1 policy responses (Bernstein Reference Bernstein2001; Humphreys Reference Humphreys2006). This school also reinforced GTC’s emphasis on problem structure by turning to relevant proxies from the scientific community, highlighted by the 1.5/2°C imperative, for interrogating whether policy and institutional responses were consistent with the problem at hand (Young Reference Young2003b).

Drift. The championing of the “sustainable development” metaphor would subtly but powerfully crowd out the prioritization school by narrowing assessments of environmental problem solving to those synergistic with human material interests (Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Mooney, Agard, Capistrano, DeFries, Diaz and Dietz2009; Bernstein Reference Bernstein2001) most recently formalized under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Bowen et al. Reference Bowen, Cradock-Henry, Koch, Patterson, Häyhä, Vogt and Barbi2017; Clémençon Reference Clémençon2021). This, in turn, has reinforced drift within the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), which was created in 1972 as the lead international organization to deliberate over and orchestrate approaches to ameliorating Type 4 ecological crises (Ivanova Reference Ivanova2021). Following fifty years of frustrations over ecological decline, UNEP has reinvented itself subtly, but powerfully, now filling its ranks with economic optimization scholars and celebrating Type 2 conceptions of nature (UN Environment 2020b, 2020a).

This drift helps explain why, despite a half-century of empirical evidence of ongoing whack-a-mole effects between ecological challenges and human material interests (Nilsson and Weitz Reference Nilsson and Weitz2019; Independent Group of Scientists 2019) (figures 1–6), and the metaphorical spotted owl example, UN-sanctioned social science assessments have proclaimed with “high confidence” (IPCC 2018, sec. 2.5.3) that synergies among environmental, social, and economic goals “far exceeds the number of trade-offs” and that any whack-a-mole effects can be averted through careful design and management of “transition oriented portfolios” (IPCC 2018, 33). They have also declared—in direct conflict with Type 4 research on species extinctions but consistent with the Type 1 commons and Type 3 compromise school’s moral beliefs—that there was “high agreement,” “high confidence,” and “medium evidence” that local community governance is central to advancing these synergies.

A closer read reveals that these conclusions pivot away from drawing on evidence of Type 4 climate change or species extinctions to researching instead the ability of humans to adapt to, rather than avert, these ecological crises (IPCC 2018, sec. 2.5.3). Tragically, these conclusions have been drawn on to advocate for “scaling up” Type 3 local collaborative processes to meaningfully reverse Type 4 human impacts on species extinctions and the climate crisis (Díaz-Reviriego, Turnhout, and Beck Reference Díaz-Reviriego, Turnhout and Beck2019; Barkin and Shambaugh Reference Barkin, Shambaugh, Barkin and Shambaugh1999; Dietz, Ostrom, and Stern Reference Dietz, Ostrom and Stern2003; Andersson and Ostrom Reference Andersson and Ostrom2008; Andersson, Evans, and Richards Reference Andersson, Evans and Richards2009).

International climate negotiations. The effects of this drift are so strong that the majority of social scientists still conclude—despite mounting empirical evidence that these Type 2 reinforcing policies have failed to achieve Type 4 outcomes (Green Reference Green2021)—that attention to economically optimal outcomes are synergistic with addressing the climate crisis as an ecological problem (Tobin Reference Tobin2020).

This belief in synergies also appears to explain the gap between the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement’s Type 4 rhetoric that the scientific evidence requires limiting temperature increases no longer to 2°C but 1.5°C to avoid catastrophic ecological damage (IPCC 2018; Clémençon Reference Clémençon2016) while promoting Type 2 reinforcing carbon pricing mechanisms as “central to prompt mitigation scenarios compatible with 1.5°C pathways” (IPCC 2018, 153). The contradictions become evident when even Nobel Laureate Nordhaus (Reference Nordhaus2017) projects, when applying Type 2 reinforcing methods, that the economically optimal solution would produce (Type 4 undermining) warming of 3.1°C above pre-industrial levels.

Tragically, economic optimization scholars have addressed these contradictions through Type 2 reinforcing debates about the level of discount rates, rather than confronting their use for determining “rational” policy responses (Sprinz Reference Sprinz2009; Winkler Reference Winkler2006; Barkin Reference Barkin2006; Hepburn and Stern Reference Hepburn and Stern2008; Heal Reference Heal1997). Similar drift helps explain why political scientists such as Victor (Reference Victor2015, 1) hailed the 2015 Paris Agreement owing to its ability to foster Type 3 compromise among competing interests even when acknowledging that the (Type 4) 1.5/2°C goal was “ridiculous” and that new (Type 3) goals were needed (Victor Reference Victor2015, 4). These conclusions stood in contrast to Type 4 climate scientist James Hansen (Reference Milman2015) who, while accepting Victor’s impact assessment, reasoned that the agreement was “a fraud really, a fake … . Just worthless words” (Milman Reference Milman2015).

Finance and Market Driven (FMD) Policy Tools

Type 4. It was in part owing to the frustration of environmental activists and Type 4 prioritization scholars with domestic and international policy responses that they turned to study “finance and market driven” (FMD) transnational policy tools originally offered in the early 1990s as a way to design more efficient and effective solutions (Green Reference Green2010; Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Cameron, Green, Bakkenes, Beaumont, Collingham and Barend2004).

Drift. Political and social science research on these governance innovations contributed to drift in two ways. First, with notable exceptions, most scholars focused on understanding the conditions through which these Type 2 reinforcing tools might gain support. Second, they emphasized “lessons learned” for policy designers to create synergies with Type 4 problems, including how to best coordinate and “stack” the proliferations of Type 2 FMD tools (Cooley and Olander Reference Cooley and Olander2011). The drift away from Type 4 problem conceptions was often reinforced by the research questions political scientists tended to ask, the methods they employed, and the type of data they collected.

REDD+

Consider widely cited research conducted by Chhatre and Ostrom’s student Agrawal (Reference Chhatre and Agrawal2009) who applied a large-N statistical analysis to assess the synergistic potential of a public and private finance tool known as “reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation” (REDD+), which was formally institutionalized at the Bali Conference of the Parties for the UN climate change convention (COP) 13 in 2007 (Ebeling and Yasué Reference Ebeling and Yasué2008). Chhatre and Agrawal concluded that, if well designed, REDD+ can foster synergies among Type 1 forest-dependent communities, Type 2 economic development, and Type 4 problems including the climate crisis and biodiversity loss. Several social scientists have cited these findings as evidence that finance- and market-driven tools have strong potential to ameliorate Type 4 environmental problems (see, for example, Persha, Agrawal, and Chhatre Reference Persha, Agrawal and Chhatre2011; Porter-Bolland et al. Reference Porter-Bolland, Ellis, Guariguata, Ruiz-Mallén, Negrete-Yankelevich and Reyes-García2012; Schmitz Reference Schmitz2018; Tobin Reference Tobin2020).

However, micro level research design choices appear to have led to drifts in empirical attention away from Type 4 problems. For example, their emphasis on “deforestation”—the common approach applied by political scientists who work on forests and climate (Lambin, Geist, and Lepers Reference Lambin, Geist and Lepers2003)—often conflates or has difficulty distinguishing Type 1 logging and Type 4 forest conservation practices (figures 1 and 6). In addition, their decision to use readily available data on “basal area” of trees as a proxy for “above-ground carbon storage” was inconsistent with key biological features of complex forest carbon cycles (Bradford et al. Reference Bradford, Wieder, Bonan, Fierer, Raymond and Crowther2016; Allison, Wallenstein, and Bradford Reference Allison, Wallenstein and Bradford2010; Griscom et al. Reference Griscom, Ganz, Virgilio, Price, Hayward, Cortez and Dodge2009). This analytic choice meant that it was not possible to infer from the data with any certainty that the REDD+ projects in question would have reduced or increased carbon emissions, let alone at levels consistent with the 1.5/2°C imperative. Most important, their analytical frames were not inductively derived from the structural features of a Type 4 problem, but rather, whether REDD+ performed relatively “better,” when combined with Type 1 decentralization governance than with existing, rather than novel, inductively designed national government policies (see also Wright et al. Reference Wright, Andersson, Gibson and Evans2016). This methodological decision is consistent with widespread norms among “data driven” forest scientists who measure the “effectiveness” of FMD tools based not on their ability to avert deforestation, but simply in reducing the rate of forest decline (Kuijk, Putz, and Zagt Reference Kuijk, Putz and Zagt2010). Differences in micro-level research design decisions may explain why, in contrast to Chhatre and Agrawal’s recommending the stacking of local communal governance with REDD+ and other transnational FMD tools, Kill (Reference Kill2019) assessed REDD+ as a time-delaying approach—consistent with Dimitrov’s (Reference Dimitrov2019) concept of a “decoy institution”—while Milne et al. (Reference Milne, Mahantya, Toa, Dressler, Kanowski and Thavata2018) found REDD+ projects to be a “blunt tool for change,” whose “dissonance between … objectives and outcomes” rendered them unlikely to provide a solution in the global climate crisis.

Certification/Eco-Labelling

Similar drift has occurred in social science research on the emergence a quarter-century ago of supply chain efforts to certify consumer goods produced through environmentally friendly practices. Some of this occurred when Ostrom’s students and followers (Prakash and Potoski Reference Prakash and Potoski2006; Kolln and Prakash Reference Kolln and Prakash2002) applied GTC’s rationalist taxonomy to conceive of eco-labeling and voluntary programs not as institutions for solving environmental problems per se, but—through its treatment of them as “club goods” (table 2)—as the resource problem itself. This led to a research program that focused attention on why utility-enhancing firms might join, and implications for the ancillary environmental impacts that might result.

Similarly, compromise school political scientists would, by treating these eco-labeling efforts as new arenas of governance (Ruggie Reference Ruggie2002), reinforce Type 3 conceptions by developing analytical frameworks that were derived from different ways in which organizations might support these systems, rather than from problem structure (Cashore, Auld, and Newsom Reference Cashore, Auld and Newsom2004; Cashore Reference Cashore2002; Bernstein and Cashore Reference Bernstein and Cashore2007). Today, many of these scholars share widespread frustration about these supply-chain governance efforts’ limited effects in ameliorating Type 4 problems (Bartley Reference Bartley2018; Grabs Reference Grabs2020). Yet until recently (Judge-Lord, McDermott, and Cashore Reference Judge-Lord, McDermott and Cashore2020), most of these scholars—notably Cashore and collaborators—reinforced drift by conflating Type 1 and 4 problems when measuring, presenting, and characterizing what they referred to as environmental regulations (Cashore and Auld Reference Cashore and Auld2003; McDermott, Cashore, and Kanowski Reference McDermott, Cashore and Kanowski2010; van der Ven, Rothacker, and Cashore Reference van der Ven, Rothacker and Cashore2018).

Conclusion: Towards “Fit for Purpose” Policy Analysis

What is evident from our review is that prevailing sustainability scholarship has narrowed an ability to ameliorate Type 4 problems to those that reinforce the moral frames of the compromise, economic optimization, and commons schools. These trends pose a philosophical puzzle for those who believe, despite fifty years of evidence to the contrary, that better designed policies can convert Type 4 whack-a-mole effects into synergies with Types 3, 2, and 1 (Prakash and Gupta Reference Prakash, Gupta and Smith1996; Costanza Reference Costanza2006): if they are correct, then there is no harm in granting species extinctions and the climate crisis Type 4 prioritization status since subsequent thoughtful policy design will mean there are no economic moles to worry about. However, if they are incorrect, the dominance of the commons, economic optimization, and compromise schools will continue to contribute to environmental decline.

To be sure, Ostrom did deliberate over the problem-solving capacity of GTC’s original framework (Ostrom Reference Ostrom2007), going so far as to acknowledge “that humans have a more complex motivational structure … than posited in earlier rational-choice theory” (Ostrom Reference Ostrom2010), but still insisted that this complexity be incorporated into efforts to improve Type 1 “[utility undermining] collective action dilemmas.” By the time of her Nobel Prize lecture she went further, but in so doing drifted away from problem structure, by advocating for universal analytical frames aimed at bringing out “the best in humans” (Ostrom Reference Ostrom2010). However, none of these deliberations led to conceiving of the climate and species extinctions crises as Type 4 challenges, nor to giving the kind of systematic empirical attention to the collection of utility undermining environmental regulations (McDermott, Cashore, and Kanowski Reference McDermott, Cashore and Kanowski2010) that she gave to Type 1 utility enhancing rules (Ostrom Reference Ostrom2005).

How then might we reverse political science’s role in accelerating Type 4 environmental crises? This is an important question, especially given the creation of two different research associations dominated by political scientists that have been formed with the expressed rhetorical purpose to help improve responses to environmental challenges: the European-based Earth Systems Governance network created by Frank Biermann that strongly incorporates compromise and prioritization schools and rigorous qualitative methods; and the U.S. based Annual Environmental Politics and Governance Conference founded by Ostrom’s student Aseem Prakash, which emphasizes economic optimization and commons scholarship and sophisticated quantitative methods.

Key themes emerge to guide this exercise for bringing the environment back in. First, since all four schools draw on strong moral foundations, calls for greater attention to “ethics” for answers—especially when doing so biases Type 3 deliberative dialogues (Beauchamp Reference Beauchamp2007)—could undermine the prioritization school’s sequentialist moral underpinnings. Recognition of this also informs debates within political science about the problems for which rational choice approaches are “fit for purpose”—such as, say, efforts to reduce humans’ inefficient use of water consumption (Leong and Qian Reference Leong and Qian2018).

Second, following GTC, we must be careful to avoid having today’s prevailing research guiding metaphors—such as “data-driven,” “evidence based,” “experimentalist,” “scaling up,” “bottom up,” “nudging,” “catalytic,” “polycentric,” “climate clubs,” “free riding,” “subsidiarity,” “internalizing externalities,” “multi-scalar,” and even “intersectionality”—reinforce policy conception drift. Third, adopting methodological pluralism that characterized APSA’s response to the 1990s Perestroika movement (Isaac Reference Isaac2015) may work to reinforce a compromise school approach that is also disconnected from problem structure. Recognition of this, in turn, poses fundamental questions about whether, by recommending interdisciplinary conversations across competing “world views” (Clapp and Dauvergne Reference Clapp and Dauvergne2005) we reinforce Type 3 conceptions over Type 4 problem solving.

Fourth, “fit for purpose” policy analysis for averting catastrophic ecological effects of climate change will most certainly involve, as an increasing number of political and sustainability science scholars now recognize, much more careful assessments of the contribution of historical institutionalism with which to deliberate over and help design policy triggers capable of producing transformative change (Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Geels, Lockwood, Newell, Schmitz, Turnheim and Jordan2018; Rosenbloom, Meadowcroft, and Cashore Reference Rosenbloom, Meadowcroft and Cashore2019; Lockwood et al. Reference Lockwood, Kuzemko, Mitchell and Hoggett2017; Webster Reference Webster2008; Geels Reference Geels2005; Jordan and Moore Reference Jordan and Moore2020; Pahle et al. Reference Pahle, Burtraw, Flachsland, Kelsey, Biber, Meckling, Edenhofer and Zysman2018). However, this turn still requires, in the case of climate change, the difficult task of distinguishing proposed triggers capable of advancing rather than overshooting a 1.5 °C future (Auld et al. Reference Auld, Bernstein, Cashore and Levin2021, 11), as well as from those rationalist scholars who derive propositions about preference changing “norm cascades” (Hale Reference Hale2020) on their ability to advance polycentric “catalytic cooperation” rather than Type 4 problem solving (ibid., 91).

To be sure, as highlighted by the German government’s feed-in tariff program, prioritization school scholars will benefit from incorporating knowledge from other schools. For example, those trained in the economic optimization school designed a cost-effective “cap and trade” tool that helped companies meet, rather than avoid, Type 4 pollution regulations for whacking the Great Lake’s acid rain mole (Burtraw and Swift Reference Burtraw and Swift1996). Similarly, the compromise school has developed useful insights for designing stakeholder dialogues to co-generate knowledge surrounding complex Type 4 problems (Cashore et al. Reference Cashore, Bernstein, Humphreys, Visseren-Hamakers and Rietig2019; Díaz-Reviriego, Turnhout, and Beck Reference Díaz-Reviriego, Turnhout and Beck2019).

What is clear from this review is that our tendency to drop the problem structure anchor when developing analytical frameworks has led political science researchers to be less equipped to incorporate scientific and policy-relevant knowledge for ameliorating a myriad of environmental problems. It therefore seems reasonable to conclude that our discipline has a duty to be transparent about the moral frames that dictate our analytical approaches and methodological choices, and the implications of doing so for either exacerbating or averting climate and massive species extinctions as the two most pressing, and soon to be irreversible, environmental problems facing our planet.

Acknowledgements

Cashore presented previous versions of this paper, or its framework, to the Copenhagen Business School’s Department of Management, Society and Communication, January 2018; the International Studies Association’s 2018 annual conference; the Ostrom Workshop, Bloomington, IN, April 23, 2018; plenary Session 3, “Climate Disorder and Public Policy: Governing in Turbulent Times,” ICPP Montreal, June 28, 2019; the Copenhagen Business School’s conference, “From Global Goals to Local Impact: Implementing Corporate Sustainability,” June 20, 2019; the Jean Monnet Sustainable Development Goals Network’s Policy Dialogue, Collaborative Approaches to Implementing the United Nations SDG Agenda, Singapore, June 13, 2019; and to the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy’s Research Seminar, May 7, 2018.

Cashore is grateful to Jeremy Moon, whose recommendation in the fall of 2017 that he expand from three problem types into four profoundly influenced this paper and related research projects. Cashore thanks Ashwath Dasarathy, Christopher Skelton, Hari Krishna, Kendra Wong, Hui Qi and Jagil Mehtab Ahmed for research assistance, and LKYSPP students in his Spring 2021 environmental and policy challenges classes who applied, and gave feedback, on the framework.

The authors thank four anonymous reviewers whose comments greatly improved the analysis and argument, and for specific comments from Guy Peters, Jette Knudsen, Michael Fotos, Noel Semple, Ken Gillingham, Lee Alston, David Konisky, Jimmy Walker, Burney Fischer, Barbara Cherry, Daniel Cheng, Eduardo Brondizio, Martin Delaroche, Jessica Steinberg, Jon Eldon, Jessy O’Reilly, Ken Richard, Karen Seto, Detlef Sprinz, Cristina Y.A. Inoue, Dimitris Stevis, Michael Maniates, Tom Princen, Michael Albert, Clayton Dasilva, Yelda Erçandırlı, Sina Leipold, Steven Wolfe, Gus Speth, Amity Doolittle, Paul Edwards, Narasimha Rao, Mary Evelyn Tucker, John Grimm, Doug Kysar, Susan Clark, Paul Anastas, Anthony Leiserowitz, Emma Shortis, Bruce Wilson, Hamish Van Der Ven, Gabe Benoit, Indy Burke, Caroline Compton, Janina Grabs, Graeme Auld, Reuben Kline, Robyn Eckersley, Neil Gunningham, Raymond Clémençon, Adam Rome, Ishani Mukherjee, Lahiru Wijedasa, Craig Thomas, Peter Christoff, Devin Judge-Lord, Hongzhou Zhang, Joshua C. Gellers, Zeewan Lee, Dan Han, Liuyang He, Ingrid Visseren-Hamakers, Ed Araral, Vinod Thomas, Derk Loorbach, Pieter Vullers, Marcel Kok, Theresa Cashore, Donna Krejci, Kelly Levin, Charlotte Streck, Daniela Goehler, and Tom Pegram.

Support for this research was provided by a National University of Singapore Start Up Grant through the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. Open access was provided by the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy’s Academic Research Support Fund.