Panama as a topic in US popular music

During the first two decades of the twentieth century, Panama was a fairly common topic in US popular music. Of the numerous subjects covered in early Tin Pan Alley songs, Panama is certainly not among the top ones. Nevertheless, the forty-seven songs identified thus far that refer to the Latin American country constitute a corpus that, despite its manageable size, is both relevant and of important historical interest. This article takes the Panama Songs as a starting point for exploring the following questions: How is Panama, as one of the first Latin American countries to be thematized in US popular song, represented in this medium? How are the different components of a Tin Pan Alley song – music, lyrics, sheet cover, performance, and recording – aligned with the representation of Panama? And what social and political context do these productions fit into and what kind of statement do they make? The answers attempted are underpinned by the thesis that the way the producers dealt with the topic was no coincidence. At this particular point in time, the United States was in the midst of a nation-building process that began after the Reconstruction era and set it on course to becoming an imperial world power. This process included redefining its relationship to neighbouring states in Latin America and demanding the construction and strengthening of its own normatively defined identity as male, white, and Protestant Christian. This required the devaluation or hegemonic subjugation of the ‘Other’, the different, the foreign, defined in terms of gender, race, and culture. The racist policies that the United States had already perpetrated on its Black and Native American populations, the ‘making of race’ through the construction of segregating ‘colour lines’ as Frederick Douglass and W. E. B. Du Bois called them,Footnote 1 processes that literally filled every sphere of life with different sorts of ‘racial terror’,Footnote 2 were now being revisited in relation to Latin America in general and Panama in particular for reasons that are discussed later. This is precisely the process underlying the production and successful reception of the Panama Songs, which at first glance might seem harmless and even joyful, but upon further scrutiny reveal deeper, more problematic aspects that will be studied and commented on in greater detail later.

So how did Panama come to be the subject of Tin Pan Alley? The songs form part of a wider phenomenon responding to the construction of the Panama Canal – ‘no other topic of popular concern in the period 1903–1915 prompted so great a volume of printed material as that generated by the events on the isthmus’.Footnote 3 The songs on the one hand join a much larger song repertoire that reflects and operates an ‘extreme exoticism’,Footnote 4 a common racial imagination in music which ‘during this same period – the early to mid-twentieth century – was … even more widespread in popular culture than in new works for concert hall and opera house’.Footnote 5 On the other hand, Panama was able to offer the early music industry and its consumers an attractive, hybrid mix arising from the general political situation, with the Canal standing as a meaningful symbol of the rise of the United States to a modern, imperialistic, globally acting state, as will be analysed in more detail later. From the perspective of the US government, Panama was another tropical Latin American country, but its most important part, the Canal Zone, belonged to the United States.Footnote 6 The foreign Other had thus been incorporated into the United States itself, and accordingly descriptions of and ascriptions to both Self and Other meet and mingle here. Unsurprisingly, the songs usually interpret these ascriptions in a way that casts the United States, its expansion and aspirations to power in a positive light.

For the relevant period of the first two decades of the twentieth century, diverse catalogues, most prominently the ones of the Library of Congress (Historic Sheet Music Collection, 1800 to 1922), university library archives (e.g., Frances G. Spencer Collection of American Popular Music, Baylor University; The Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Johns Hopkins University; Historic US Sheet Music Collection, University of Illinois; Charles Templeton Sheet Music Collection, Mississippi State University),Footnote 7 and exhibition cataloguesFootnote 8 contain at least forty-seven pieces of music from the United States that refer explicitly to Panama. We see that Panama starts to attract attention in US popular music shortly after 1900. From 1903 onwards, following Panama's independence and the intervention of the United States in its territory, the country becomes a regular topic of music (Table 1).

Table 1 List of songs, marches, and dances referring to Panama between 1880 and 1922

There is a marked rise in the number of songs between 1913 and 1915 around the Canal's completion, not least in connection with the Panama–Pacific Expositions in San Diego and San Francisco in 1915. These exhibitions focused exclusively upon Panama; after all, the building of the Panama Canal was ‘one of the largest (if not the largest) imperial projects in US history’.Footnote 9 The United States thus used the expositions both to celebrate the opening of the Canal on US soil, after the original celebrations had to be cancelled due to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, and to highlight the achievements of the nation as a strong new actor on the global stage. Among other things, the exhibitions featured gigantic models of the Panama Canal (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Model of the Panama Canal at the 1915 Panama–Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. Photo: Charles Caldwell Moore. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

It was not only these expositions that staged the Panama Canal for entertainment purposes, however. Broadway's musical theatres turned it into a stage sensation, as in the case of the show America. A Musical Spectacle from the 1913/14 season (Hippodrome Theatre, music and lyrics by Manuel Klein), which presented several historical events and key locations in the United States, from the landing of Columbus to the opening of the Panama Canal. The Panama episode depicted the first passage of a ship through the Canal, framed by musical numbers such as ‘Tango’ (native dancers) and ‘Grand Celebration Parade’ (company), and was, according to the newspaper critics, the ‘most jaw-dropping moment’ of the evening.Footnote 10

After 1916, interest in Panama dropped off sharply. Entry of the United States into the First World War in 1917 now became the new centre of attention, including where the formation of a national identity was concerned.

The Panama Songs themselves do not constitute an extraordinary, atypical corpus of music that would have to be approached using a special method of analysis. On the contrary, in terms of genre, songwriters, publishers, performers, and cover artists associated with the marketing, the music moves within the realm of the classic Tin Pan Alley productions of the period. The Panama topic fits into the Alley's ‘general devotion to stereotyped ethnic and racial representation’.Footnote 11 The composers and lyricists include familiar names such as Gus Edwards, Edward Madden, Alexander Rogers, Vincent Bryan, William Tyers, John Philip Sousa, Julius Johnson, and J. Bodewalt Lampe. The firms of Jerome H. Remick, Leo Feist, C. H. Ditson, Shapiro, Bernstein & Co., and Whitney Warner Publishing in New York, Chicago, Boston, and Detroit represent the publishing heart of Tin Pan Alley. Cover artists such as Bert Cobb, Frank W. Starmer, and Edward H. Pfeiffer illustrated countless editions of sheet music, and singers such as Tom Brown, Maurice Hayes, Arthur Collins, Billy Murray, or Nat M. Wills, who had some of the songs in their repertoire and also recorded them for the Edison Phonograph and Victor Talking Machine Companies, were popular stars whose image on the sheet covers was a further incentive to buy the songs. The Panama Songs were not just typical Tin Pan Alley productions, but also circulated widely. The quintet song ‘Lola, the Fairest Daughter of Panama’ (No. 18), for example, was part of the most successful show on Broadway in 1913/14, the abovementioned America. A Musical Spectacle, which ran for an entire year and was shown 360 times.Footnote 12 Before exploring this music (mostly songs) and the means through which it seeks to represent Panama, as well as investigating the question of the extent to which this music was employed to shape the US perception of the country, I would first like to take a closer look at the historical political background in order to then introduce the repertoire, its music, lyrics, the design of its cover illustrations, and the performances on recordings.

The United States and Panama: a history of mutual dependence

Panama occupies a special position in the history of Latin America.Footnote 13 Central America's southernmost country is small and somewhat inconspicuous, without any significant mineral resources. Panama is tropical, which means that the dry season lasts only from January to March and some regions see continuous rainfall for the rest of the year. It is always hot, and there is a risk of malaria, cholera, and yellow fever. Parts of the country are made up of swamps and rain forests so impenetrable that even the world's longest highway, the Pan-American Highway from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, has a gap of about sixty-five miles at this point. Panama has another ‘treasure’, however. Between Colón and Panama City, the country is only about fifty miles wide, forming a narrow isthmus that separates the world's two oceans, the Atlantic and the Pacific. For this reason, Panama has always been of interest for East–West trade, as circumnavigating South America around Cape Horn means a journey of 9,500 miles. A shipping route at Panama's narrowest point makes faster, less risky trade between East and West possible. The idea to build a canal there already arose shortly after Christopher Columbus set foot on the Antilles and the early conquistadores began to ‘discover’ and conquer the continent in the name of the Portuguese and Spanish crowns. However, it took until the second half of the nineteenth century before a first attempt was made to put this idea into practice. This project, led by the French architect Ferdinand de Lesseps, ended in failure in 1889 due to disease and the challenges posed by Panama's climate and geography. De Lesseps had previously built the Egyptian Suez Canal (a parallel colonial project designed to reduce the distance between Europe and the ‘Orient’ and thus facilitate the expansion of Western power). The collapse of the Panama Canal project was a financial disaster that plunged not only the specially founded Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interocéanique and many of its financiers, but also the French government into major crisis. It also initially dashed the hopes for Panamanian economic and political independence that had been associated with the Canal's construction. Panama had declared its independence several times over the course of the nineteenth century: in 1821 from Spain, in 1830 from Gran Colombia, and in 1840 from New Granada, a declaration that was to be sealed by a separate constitution of the Estado del Istmo (as the country then called itself). However, this independence was short-lived, for in 1841, Panama was re-integrated into the República de la Nueva Granada – albeit now with autonomous rights. This state of affairs continued by and large until 1903, a period marked by experiments ranging from self-government to the downgrading of the country to a mere department.

The United States became aware of Panama's attractiveness in the mid-nineteenth century, increasing its efforts to win the contract for a canal construction project in direct competition with France and Great Britain.Footnote 14 After adopting a policy of expansion, the United States had emerged victorious from the Mexican–American War in 1847, and now its territory extended west of the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific, including Oregon and California, where gold had been discovered. The gold rush led to a mass migration through Panama, mostly of US citizens. The trans-isthmic railway was built in this context. Its completion in 1855 led to the establishment of large commercial markets in Colón and Panama City. Panama became a US protectorate.Footnote 15 Racial and social conflicts arose alongside this flourishing trade, however, as illustrated by the riots over a piece of watermelon that became known as the ‘Watermelon War’.Footnote 16 The waning of the gold rush after 1854 led to a corresponding economic decline in Panama. Despite this, the United States's economic interest in the Canal continued unabated. Moreover, Panama's military importance became clear at the latest with the 1898 Spanish–American War, as the US war fleet needed to get from the west coast of the United States to the Caribbean, something that could only be accomplished by sea, not by rail. After the warship USS Oregon had taken sixty-eight days to travel from San Francisco to Cuba via Cape Horn, the military put further pressure on the government to commit itself to the construction of the Canal. Accordingly, around 1900 the United States had a considerable economic and military interest in acquiring Panama's ‘treasure’ itself after de Lesseps's failure, that is, in building and operating a canal there. In order to do so, they needed to control the country, which by this time was on the road to independence. The Roosevelt administration (1901–9) pursued this aim single-mindedly. In 1902, it decided against the initially preferred Nicaragua Canal option in favour of Panama, entering into negotiations with Colombia. These talks ultimately failed as Bogotá continued to vacillate and demanded major compensation. So, the US government instead pledged its military support to Panama's insurgent movement, and on 3 November 1903 Panama once again declared its independence, backed by the US navy. Panama was immediately recognized internationally as a state. But instead of gaining true emancipation, the country once again became trapped in a state of pseudo-independence or postcolonial dependence:

The Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty [18 November 1903Footnote 17] … provided for the de facto division of the country by a zone [ten miles wide] of exclusive foreign administrative sovereignty. In this zone, the United States was given all the freedoms and powers it deemed necessary with regard to construction, maintenance, operation, health care and the protection of the canal, which it was allowed to exercise ‘as if it were the sovereign[’].Footnote 18

Thus, at a sensitive point in the nation-building of both states, a de facto colonial relationship existed between the expanding United States, which was soon to challenge the European powers in the capitalist value system, and Panama, which was unable to establish autonomy on its own. This state of affairs in principle lasted until 1979, insofar as US governors were appointed in Panama until that year, when the Carter administration ‘returned’ the Canal Zone to its former owner. This relationship is captured by Aníbal Quijano's concept of coloniality (colonialidad),Footnote 19 which seeks to describe that ‘historical paradox of independence under the control of the same groups that had ruled in colonial times’.Footnote 20

We need to bear this in mind over the course of the following remarks, which will focus on the dominant image of Panama in the United States between 1900 and 1920, an image that also found expression in forms of popular music. The major power's explicitly and inevitably neocolonial perspective on its smaller counterpart is itself an expression of power aspirations and therefore necessarily is one-sided. US nation-building is inseparably linked to the United States's dealings with Latin America. While the United States's political relations with and foreign policy on Latin America served mainly to stimulate its political, economic, and finally military expansion into a world power, its cultural interest was and is also characterized by a fascination with the Latin American ‘Other’, which promised to both reflect and enrich expressions of the United States's own culture. The United States's quest for a cultural identity of its own was characterized particularly by strategies for negotiating processes of appropriation and dissociation. The history of the United States – like that of all other American territories – begins with its emancipation from its colonial status and thus represents a process of postcolonial self-discovery. In addition to the dissociation from and appropriation of elements of the European ‘mother cultures’, there has also been a dissociation from and appropriation of aspects of Latin America. This development set in at the latest in the mid-nineteenth century, when the initially pan-American, anti-European Monroe Doctrine (1823) was increasingly abandoned in favour of asserting the United States's own interests in the two Americas. After winning the Spanish–American War in 1898, Cuba was granted its independence and the United States gained the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, and Hawaii was annexed. In the United States, an image of the Latin American world thus emerged that initially represented it as an Other of the United States – and thus a part of the United States – well into the twentieth century. According to Walter Mignolo, it was here that the defining idea of Latin America was first constructed.Footnote 21 Following increased migration from Mexico, the Caribbean (especially Puerto Rico), and the states of Central and South America to the United States, these aspects of the Other gradually involuntarily became part of the United States's own identity. Today, we can speak of a Hispanization or Latin Americanization of the United States as part of globalization, a development the Mexican poet Carlos Fuentes has called ‘reconquista’.Footnote 22 The beginning of this process, its first step so to speak, is the United States's more or less colonial perception of Latin America at the beginning of the twentieth century. The present article aims to investigate this perception in greater depth, using the example of US popular music referring to Panama to do so. It explores the ways in which the United States, as a colonial power, constructed its pseudo-colony or postcolony Panama as an Other in order to exercise a certain form of influence there and in doing so continue to shape its own national identity. It enquires into the discourses taking place within the cultural practice of popular music rather than focusing primarily on the political and economic conditions outlined earlier, although these of course form the historical context for the music examined.

Musical representations of Panama

The Panama Songs were written at a time when US popular music had turned its attention to Latin American music, adopting a ‘Latin tinge’Footnote 23 to provide its tunes with a touch of exotic interest. The nature of the music stemming from the diverse Latin American cultures, however, had not yet been subject to scholarly investigation, neither in the United States nor in Europe.Footnote 24 Pioneering ethnomusicological studies such as Carlos Vega's reconstruction of pre-Columbian musical systems and instrumentsFootnote 25 or Narciso Garay's investigation of Panamanian musical styles such as the Tamborito or the MejoranaFootnote 26 date from the early 1930s. A few years earlier, during the 1920s, German ethnomusicologists Theodor Koch-Grünberg and Erich von Hornbostel published their Vom Roroima zum Orinoco: Ergebnisse einer Reise in Nordbrasilien und Venezuela in den Jahren 1911–1913,Footnote 27 which include analyses of recordings that date back to 1903. But around 1910, a mere ‘Latin tinge was well established in a wide range of US popular styles, and that tinge itself ranged from the more or less overt presence of Mexican melodies to an underlying Cuban rhythmic strain. On Tin Pan Alley, these Latinisms were still only a seasoning, hardly more important than Italian music and much less so than Irish’.Footnote 28 But even though – or perhaps precisely because – the musical references functioned merely as ‘seasoning’, they allow us to identify numerous traces of neocolonial discourse in the Panama Songs. As in other ‘exotic’ songs, no specific extended musical idioms are used here; rather, exoticizing musical cuesFootnote 29 are given through specific rhythms, references to dance forms, or melodic inflections. As a consequence, the songs do not function as audible representations of Panama itself but serve as examples of one of the earliest Latin waves in US popular music, and as a trace of how both the United States as a nation and its fast-growing cultural industry defined the dominant role of the United States in the relation to its southern neighbour, here through the means of musical entertainment.

The corpus essentially is made up of three musical genres that correspond with this period's most popular musical forms. The individual pieces’ reference to Panama does not always go beyond their title (e.g. the ‘Panama Route Waltz’ by Arthur Maylath, Table 1, No. 1). However, the specific references can be characterized as follows for the different genres:

1. Marches or music for brass bands full of patriotic fervour with speaking titles such as ‘Hero of the Isthmus’ (No. 10), ‘Salute to Panama’ (No. 37), or ‘The Pathfinder of Panama’ (No. 39) celebrated the construction of the Canal as both a military and a technical achievement.Footnote 30

2. Songs with diverse aims. They often cast the Canal in a positive light as connecting two lovers in a romantic, exotic idyll. The Canal serves as a symbol for the linking of opposites such as East and West, North and Latin America, man and woman, technology and nature, civilization and supposedly uncivilized cultures. They also express the romantic utopian longing to merge with the Other, with nature, with the simple. By contrast, some of the songs caricature and criticize the national and hegemonic canal-building enterprise in a satirical manner.

3. Finally, dances or dance songs were keen to give the fashionable dances already widespread in the United States a foreign, ‘Panama-esque’ touch, sometimes with a satirical undertone.

J. Louis von der Mehden's musical journey in his descriptive fantasy ‘Through the Panama Canal’

Our first example comes from the genre of music for brass bands. It is tempting, of course, to see the dominance of the march that characterizes this musical homage to the canal project as confirming the endeavour's military, politically aggressive character. Marches such as ‘Salute to Panama’ by Julius K. Johnson, written in 1907, or ‘Hero of the Isthmus’, which J. Bodewalt Lampe composed in 1912 for Colonel Goethals, the chief engineer of the Panama Canal and later first governor of the Canal Zone, as well as John Philip Sousa's 1915 ‘The Pathfinder of Panama’ all carry their mission in their titles. However, we should bear in mind that the march was generally widespread during this period insofar as the genre can be regarded as the core of popular music in general. Marches by Johann Strauss Jr, Edward Elgar, and Sousa were played in concert halls and on roadsides, there were scarcely any ceremonies that did not feature a marching brass band, and marching music provided key impulses for ragtime and jazz in the form of Dixieland. Incidentally, marches were already adopting elements of Latin American music; for example, the Cuban habanera rhythm in the bridge of W. C. Handy's ‘St. Louis Blues’ (1914). Accordingly, the negotiation of the Panama theme in marches is a completely normal process, especially as the music itself remains unspecific despite the differences in quality between the various pieces. ‘Through the Panama Canal’ (No. 14) of 1913 stands out particularly, however. The name says it all. The composer J. Louis von der Mehden (1873–1954)Footnote 31 imagined the first ship passing through the Canal, writing at a time when the Canal had not yet been completed. The subtitle ‘A Descriptive Fantasy’ refers to ‘descriptive music’, a subgenre of marching band music that had gained popularity especially with Sousa. Its typical features were, first, its inclusion of sounds of the environment, especially technical objects (e.g., clocks, gunshots, sirens, signals, locomotives), and, second, its combination of familiar melodies from other pieces of music (e.g., opera, operetta, marches, popular and church songs) into a potpourri, the arrangement of which often encouraged a narrative interpretation – in the programmatic sense.Footnote 32 Von der Mehden's Fantasy accordingly employs topical musical gestures, the sounds of a ship's bell and foghorn, to create the atmosphere of a journey by boat. It culminates in a sequence of patriotic songs and national anthems whose selection is anything but random. The piece follows the programmatic design typical of the genre: the first half is concerned with presenting naval sounds interspersed with some musical transitions. This acoustically represents the ship's voyage through the Canal. The second half, however, turns the acoustic ‘description’ into a symbolic interpretation using pre-existing music – songs and anthems – in order to give deeper meaning to the journey. The following description is based on a historical recording made by the Victor Military Band.Footnote 33 The whole passage consists of six episodes, each of which is linked to one popular melody. First (a), we hear a Latin- or Spanish-tinged section, the source of which has not yet been identified. It could be a dance or march/rag tune famous at the time, a melody from an opera or operetta, or a song; it could also be an original invention by the composer. What is important here is the Spanish or Latin flair created by the use of castanets and a habanera/tango-like rhythm. The ‘Spanish/Latin’ passage is followed by (b) a British one, in fact the most British one possible, featuring a short excerpt from ‘Rule Britannia’. After this we hear a few bars of the French national anthem ‘Marseillaise’ (c), which leads directly to the patriotic German nineteenth-century song ‘Wacht am Rhein’ (‘Watch on the Rhine’) (d). Significantly, three patriotic and nationalistic US tunes form the conclusion: (e) ‘Columbia, Gem of the Ocean’ with some material taken from (f) ‘Yankee Doodle’ in the piccolo, and finally (g) ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’, which later was to become the US national anthem. The sequence of national songs and anthems translates the spatial idea of the ship's passage into the chronological, historical domain, marking different stages in the Canal's history.

The first stage symbolizes the former traditional colonial relations: the Latin American country Panama ‘sounds’ like a Spanish colony. Spain was also a rival to the United States in its striving for global power, a rival finally defeated in the war of 1898. After ‘Spain’ we hear ‘Britain’ and ‘France’, the two other major colonizing countries in the Americas and the United States's early competitors in the run-up to the building of the Canal. Moreover, the ‘Marseillaise’ is a musical symbol of civil rights revolutions, of past struggles for freedom, which in the case of the wars of independence of both the United States and Panama led to their liberation from British and Spanish colonization respectively. (In an act of adopting and transferring the colonizer's identity to that of the colonized people, the melody of ‘Rule Britannia’ was also used for the US revolutionary patriotic song ‘Hail, Columbia’.) However, the ‘Marseillaise’ also stands for the one other nation that had failed in its first attempt to build a canal in 1889.

This fact explains the next borrowed tune and the symbolism of the next stage. The melody of the German composer Carl Wilhelm (who, like von der Mehden, was a freemason) for a setting of Max Schneckenburger's poem ‘Wacht am Rhein’ is inseparably linked with the idea of a German Reich, and, especially since the Germans’ victory in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71, with the containment of the French Empire. The text explicitly calls for the military protection of the banks of the Rhine from annexation by French troops. It defines France as the enemy and a threat to the order of the European empires since the middle of nineteenth century. Von der Mehden, who had studied music at the Leipzig Conservatory between 1892 and 1894, must have been acquainted with the political significance of this tune, which functioned as the unofficial national anthem of the Kaiserreich alongside ‘Heil dir im Siegerkranz’. Its use in the context of celebrating the United States's successful construction of the Panama Canal not only points directly to France's failure some decades previously, but also celebrates this failure and calls for the protection of the shores of the Canal, that is, the formation of a US-controlled Canal Zone.

This episode gives way to the next and final stage, which demonstrates the United States's power and claim to global leadership. Significantly, following a short passage from ‘Columbia, Gem of the Ocean’ – another patriotic song that was one of the unofficial anthems of the United States during the nineteenth and early twentieth century – ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ forms the conclusion to the piece. Following the principle Finis Coronat Opus, this ending both crowns and dominates the piece – not only in musical, but also in ideological terms. The message is clear: Panama's glorious future begins with the supremacy of the United States, which planned and executed the construction of the Canal. It will operate and control the Canal by establishing a US territory. The three historical stages thus come together to form a three-step historical development towards US hegemony. The music propagandizes and legitimizes the United States's imperial, colonizing actions through its historical perspective.

The colonial gaze: cover illustrations

Three illustrations used on the covers of sheet music editions of Tin Pan Alley songs serve as examples of the United States's perception of Panama. Cover art in general was highly important, since its appeal ‘was recognized as a link in the success of selling sheet music … [Thus] from the mid-1890s on, publishers took great care with their covers’,Footnote 34 and the work of artists (such as Bert Cobb or Frank W. Starmer) was crucial for the promotion of the songs. Moreover, the illustrations studied here show ideas about Panama that were widespread in the United States, although they employ different codes and symbols of colonial discourse to do so, such as racism, exotic othering, and military suppression. These cover pages thus reveal constructions of alterity, of colonial and neocolonial relations of power and domination.

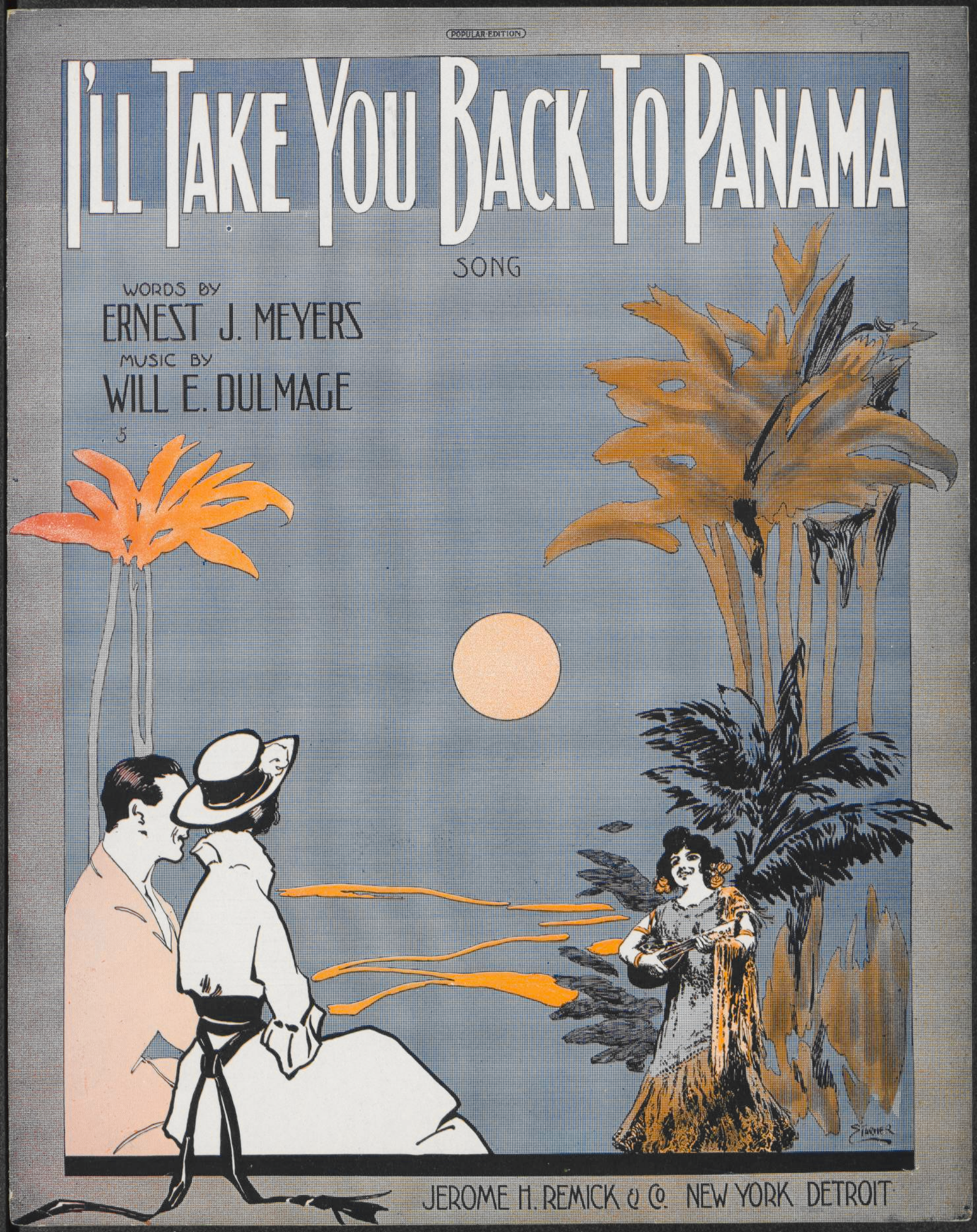

The cover of the romantic song ‘I'll Take You Back to Panama’ (1914, No. 24) depicts a (as far as one can tell) white, supposedly US-American couple, the ‘we’ of the lyrics, seated in a tropical setting under palm trees at night (Figure 2). A woman dressed in an exotic folk costume sings and plays a serenade (on a guitar instrument).Footnote 35 Here, Panama is portrayed as a romantic, sultry idyll full of foreign music, far away from the economic burdens and worries of everyday life. The song constructs a tropical ‘paradise’, staging the exotic Other as a place of longing. For ‘most of all, it was popular song that, during the early and mid-twentieth century, served as a vehicle of vicarious travel to Other places’.Footnote 36 The newly acquired territory in Panama appears as an attractive tourist destination, an asset for consumers in the United States whose attention and curiosity were beginning to be directed to different world locations by various media products, such as the National Geographic Magazine (founded in 1888) or songs. Here, we can observe how a culture recognizes itself through the projection of an Otherness as different as it is fascinating.Footnote 37 For longing for the Other is always also one's own longing and thus part of the Self.

Figure 2 Cover illustration of ‘I'll Take You Back to Panama’ by Ernest J. Myers and Will E. Dulmage. Source: University of Maine, DigitalCommons@UMaine.

A very different musical genre, namely the march, is promoted by the cover of the ‘Hero of the Isthmus’ (1912, No. 10) (Figure 3). The title refers to the Panamanian isthmus, and the music celebrates the US-born civil engineer in charge of building the Panama Canal, Major General George Washington Goethals (1858–1928), as a heroic military commander, a new type of hero, a soldier-engineerFootnote 38 in a challenging mission. The cover thus presents his portrait photograph between a guard of honour made up of two uniformed soldiers bearing sabres. Between 1909 and 1916, Goethals ran the Canal's affairs ‘as a virtual dictator’,Footnote 39 and the march illustrates the essentially military dominance of the United States over Panama, the construction and justification of North American power. This reveals an essential goal of neocolonial discourse, namely ‘to construe the colonized as a population of degenerate types on the basis of racial origin, in order to justify conquest and to establish systems of administration and instruction’.Footnote 40

Figure 3 Cover illustration of ‘Hero of the Isthmus’ by J. Bodewalt Lampe (1912). Source: Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Johns Hopkins University (Box 171, Item 009).

The cover of the ‘Panama Rag’ (1904, No. 4) once more presents a tropical landscape. Additionally, it shows a Black man wearing a Panama hat (Figure 4). There is no song from the period studied that associates the wearing of this item of clothing, which became increasingly fashionable from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, with a white person. The Panama hat, of Ecuadorian origin, got its name because of the lively trade in Panama and the customs stamp associated with it. Furthermore, it is linked to the construction of the Canal in a range of different ways. The workers, most of them Black women and men from the Caribbean, namely from the British-ruled sugar plantations on Barbados,Footnote 41 wore it as a sunshade, which is evident in photographic documentations of the construction site.Footnote 42 Moreover, there is a famous 1906 photo showing President Roosevelt, among several others, wearing it during his visits to the site as well;Footnote 43 a sign, therefore, of the appropriation of an originally local product – a product that represents a centuries-old tradition of craftsmanship as a filigree handmade from bleached fibres of the toquilla straw – by an imperial power, which ultimately transformed it into a best-selling high-society accessory. The cover image's combination of stereotyped African and Latin American elements confronts the North American consumer with a twofold Other, a combination of ethnic differences that is particularly characteristic of Latin America as a sphere of transcultural encounter, a hybrid cultural area. Above all, however, the cover of the ‘Panama Rag’ draws on an extremely popular and openly racist model of US song, namely the so-called ‘coon song’ as a subgenre in general and the 1902 song ‘The Coon with the Panama’ (No. 2) by Alexander Rogers, Jim Vaughn, and Tom Lemonier in particular. Likewise composed as a ragtime, ‘The Coon with the Panama’ formed part of the repertoire of singer and actor Tom Brown, depicted on the song's cover as an African American dandy, the minstrel show's ‘Black Dandy’ character (such as Zip Coon), wearing a Panama hat (Figure 5) and aiming to live above his ‘standards’ by mimicking white, ‘upper-class’ dress. As a ‘coon song’, ‘The Coon with the Panama’ comes from a tradition of racist songs that were created in minstrel shows and became a real fad between 1880 and 1910. Authors and performers of coon songs included both white and Black people, not seldom singers in blackface; for African Americans, minstrel shows, and coon songs were often the only way to work in the music business at the height of racial segregation. Tom Brown was one of these vaudeville and minstrel artists specializing in the presentation of hybrid cultures. In the famous show A Trip to Coontown, he also played a Chinese character in an example of an African American doing ‘yellowface’.Footnote 44 ‘Panama Rag’ and the coon songs ‘The Coon with the Panama’ and ‘Under a Panama’ (No. 3) all demonstrate a strong link between the topic of Panama (or, more generally, the influence of Latinness represented by the fashionable hat from Ecuador), Blackness (the so-called ‘coon’) and racism. Here, stereotypes of Blackness and Latinness are combined, which may even have served as a functioning (racist) representation of Panama itself, given the historical importance of its Afro-Latin cultures. The historical background to this combination of stereotypes is the fact, not necessarily known to the songs’ contemporary audiences, that the majority of African American inhabitants of the United States (and the former colonies respectively) had not reached the country directly from Africa but were kidnapped and then enslaved on the Caribbean sugar plantations before being sold on to the North American territories. And like the Caribbean, Panama was an Afro-diasporic site in the history of enslavement and ethnic migration. But as the critical analysis of the covers shows, to the US imagination, Panama with all its mixed cultural elements was not really a place of racial ambiguity or affirmed difference. Rather, the possible racial hybridity between categories such as ‘Hispanic’, ‘Spanish’, ‘Black’, ‘Latin’, ‘Black-Latin’, ‘creole’, or ‘mulatto’ was more commonly used to ascribe the same set of stereotypes to these diverse groups of people, who were simply marked as ‘ethnic’ and ‘exotic’.Footnote 45

Figure 4 Cover illustration of ‘Panama Rag’ (1904) by Cy Seymour. Source: Charles H. Templeton, Sr sheet music collection. Special Collections, Mississippi State University Libraries (Box 145; Folder 1; Piece 25).

Figure 5 Cover illustration of ‘The Coon with the Panama’ (1902) by Alex Rogers, Jim Vaughn, and Tom Lemonier. Source: Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Johns Hopkins University (Box 145, Item 162).

A host of further illustrations could show that these constructions and stagings of the Other and the incorporation of these constructions into an unequal, asymmetrical exercising of authority and power are topics through which the United States negotiated its relationship to Panama in early twentieth-century popular culture. This relationship was characterized precisely by the neocolonial structures through which the United States was able to strengthen its own national identity as a ruling power, ultimately casting itself as a future hegemonic global force.

The ‘sonic color line’: sound recordings

Some of the musical pieces related to Panama have survived not only as sheet music and corresponding cover illustrations, but also in the form of sound documents. Early recordings of popular music give us another complementary insight into the processes of exchange and negotiation between different cultures or cultural groupings. Lisa Gitelman speaks of the fact that

American culture, economy, and law in the years around the turn of the century demonstrate that mechanical reproduction at home remained decisively charged with the complexities of that intercultural nexus, a site for participating in experiences of self, identity, and difference. Not only could consumers purchase the recorded hits that ‘everybody’ liked but also they could negotiate difference in the varying cultural valences of Italian opera, ‘classical music’, ‘exotic’ records from around the world, ethnic records for immigrant niche markets, Simon Legree, coon songs, and burlesques. Differences of class, nation, and race were maintained: phonographs became instruments of ‘sacralization’, helping to distinguish culture as such, and they also became instruments for the maintenance of ethnic identity in the face of assimilationist pressure.Footnote 46

Listening to early recordings of music with a Panamanian reference underlines the thesis posited on the basis of the illustrations that with Panama another ethnic connection enters the negotiation process, but not in order to achieve greater differentiation or hybridization, but ultimately in order to preserve US identity in the confrontation with the Other.

In the recording of von der Mehden's ‘Descriptive Fantasy’ by the Victor Military Band, the ‘Panama episode’ stands out clearly thanks to the sound of the castanets and its habanera rhythm. However, it merely forms a middle step in the ‘journey’ from the fragmented ambient sounds of the opening to the radiant ‘Star-Spangled Banner’ concluding the work. The explicitly ‘exotic’ Spanish sound is neither the starting point nor the destination of the undertaking, but a transitional stage; a sound, therefore, that stands out by virtue of its appeal but is not intended to be the final outcome of the teleologically conceived process. The listener is thus made sonically aware of the hierarchical imbalance that determines the political and cultural negotiation process between the nations associated with the construction of the Panama Canal – a process that ultimately culminates in the sound of the ‘US anthem’, the kind of sound associated most strongly with the performance of a military band. The piece uses the sound ascribed to the neighbouring Panama at most as a means to an end, as a station on its way.

When it comes to Panamanian coon songs, the goal to maintain white Anglo-Saxon supremacy by establishing sonic markers becomes equally obvious. In contrast to live performances of these songs, white singers did not have to dye their skin colour black for the recording; instead, they strove to endow their voices with those characteristics that were considered ‘Black’ according to the prevailing constructed notions: ‘Invisible coon-song performers were supposed to “sound black”, according to long-lived, raucous, and racist norms of seeing, sounding, and blackness.’Footnote 47 Their representations contributed significantly to the construction of a ‘sonic color line’Footnote 48 analogous to the visual one. At the turn of the century, the sonic colour line explicitly localized the ‘coon’ elements in the realm of Latin America as well. Thus, these songs show a projection of the Panama fashion into the standard musical ‘coon-isms’ of the day. ‘Sounding black’ is, of course, a vague and inherently racist-essentialist attribution that runs the risk of entrenching stereotypes when one attempts to apply it analytically today. Around 1900, it could refer to certain racial markers, such as the ragtime song setting, a deep, sonorous voice, or singing practices that had been handed down on the minstrel stage, such as ‘a southern accent making “correct” and pure vowel sounds more malleable; using the lower, speaking register of the … voice as the general tessitura; an expressive flexibility of tone enhanced by the closeness of the speaking with the singing voice’.Footnote 49 ‘Under a Panama’ has survived in two different recordings. They date from the same period, 1903 and 1904 respectively, when coon songs were at the height of their popularity. The lyrics recount a conversation between Bill and Lulu. Bill is said to sing a song about an ‘African Coon’ and to paint a picture of a carefree life together in Africa, on the Congo, under a bamboo tree. This is probably a reference to the well-known coon song ‘Under the Bamboo Tree’, which had been very successful in 1902, the previous year. Lulu, however, brusquely rejects the idea of such a ‘primitive’ life as something for ‘Zulus’. She wants a husband who acts as if he were civilized and sophisticated and has a city apartment, an automobile, and, last but not least, a Panama hat: ‘No coon can win out Lulu, unless he's under a Panama’, she states in the chorus. The recorded singers are Arthur CollinsFootnote 50 and Billy Murray,Footnote 51 two stars of early song recordings. The baritone Collins ‘was one of the greatest performers of coon songs, and one of the half dozen most popular singers on record’.Footnote 52 He was especially popular for his rendition of what was considered and parodied as ‘Black dialect’ among white consumers. Unfortunately, his recording of ‘Under a Panama’ could not be accessed, but the following press release from 1905 ‘Mr. Collins is Not a Negro’ suggests that he was particularly effective in meeting the requirements for ‘sounding black’: ‘Possibly because of his great success in singing coon and rag-time songs for the Edison Phonograph some people seem to have gained the impression that Arthur Collins is a colored man. Such an impression is naturally amusing to Mr. Collins. It is complimentary, however, to imitate the colored race so closely as to be mistaken for the real article.’Footnote 53 Billy Murray's background likewise was the minstrel show, where he performed in blackface for Al G. Field's Greater Minstrels. The voice we hear in his recording is not sonorous and deep but sharp and nasal. He noticeably emphasizes certain words such as ‘moon’, ‘coon’, ‘Lulu’, ‘Zulu’, ‘Congo’, and ‘canoe’ by elongating the vowels and pronouncing them in a particularly nasal manner. Furthermore, some words in the refrain (‘auto’) and in Lulu's direct speech in the second verse are spoken rather than sung, enhancing ‘the closeness of the speaking with the singing voice’ and thus underlining the racist content and the effect as a parody of African Americans.

The racist component of the behavioural patterns of the dominant white population in the United States, associated with the appropriation or de facto expropriation of cultural goods such as music (e.g., ragtime, certain singing styles) or forms of clothing (such as the Panama hat), is clearly evident in the coon songs referring to the hat and the recorded performances of these songs by former minstrel artists. These recordings associated the white people's lifestyle item ‘Panama hat’ with the Black population's striving for recognition without any prospect of success, and at the same time ridiculed them with their vocal performance style.

Music and lyrics

In the lyrics set to music (as in politics), the Panama Canal, built by the United States between 1904 and 1914 using Black Caribbean labour, forms the main subject matter, the major focus of interest wherever Panama is concerned. In the words of Alexander Missal, ‘the Panama Canal was a construction site, filled not only with mud and water but with meanings as well’.Footnote 54 Analogously to the ‘Panama authors’Footnote 55 writing popular books and articles for magazines, the ‘Panama songwriters’, as I call them, took up the task of formulating images and interpretations of the ‘miracle’ of the construction of the Canal in a tropical environment for the new middle class (the employed national consumer) emerging at some point between the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. The Canal and its construction were repeatedly promoted as humanity's greatest technical achievement and a significant milestone of human progress. President Roosevelt even gave a philanthropic twist to this mainstay of US expansion, speaking of the ‘civilization’ of chaotic and weak governments and claiming to act ‘in the interests of humanity’.Footnote 56 These proto-missionary justifications tie in with a topos that forms an integral part of colonial discourse, according to which the colonizing power, as the superior civilization, rises above the supposedly ‘barbaric’ or at least ‘primitive’ colonized with the aim of nurturing and supporting the latter according to the colonizer's own ideas and values.Footnote 57 However, the colonialist structure of this undertaking did not go unnoticed by politics, journalism, and entertainment culture, and thus the construction of the Panama Canal repeatedly became the subject of satire. The hegemonic thrust of North American politics was openly caricatured. The popular music documenting this political satire comes less from the time of the opening of the Canal and more from the Roosevelt era, that is, the era of the president who not only propagated the mental attitude described earlier, but also set an example of it himself. He thus constituted an excellent target, for example in the song ‘Theodore’ (No. 5), which Vincent Bryan, who also wrote coon-song lyrics such as ‘Under a Panama’, composed in 1907. The song's lyrics portray the president as a pompous potentate, a power-conscious presence on the world stage who tries to solve foreign policy problems with ‘big stick’ diplomacy, true to his motto ‘Speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far.’Footnote 58 The construction of the Panama Canal is a key element of this policy and thus also of the song. Verse 5 and the following chorus interpret the Canal's significance for Roosevelt in the context of US relations with Japan. In 1906, Roosevelt had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts in the settlement of the Russo-Japanese War. The song's choruses thus refer to him as ‘Our Theodore, the peaceful Theodore’. The Canal, by contrast, would provide him with a strategic means of taking quick, efficient military action in the event of an armed conflict with the Japanese, here referred to by the racist term ‘Japs’:

The text is concerned with the imperialistic aggression behind Roosevelt's foreign policy and military strategies, revealing the true aims of the Nobel Peace Prize winner's words and actions – that is, establishing and defending white US supremacy. The parodist's music emphasizes this by striking an official, nationalistic tone: a march-like idiom, a hymn-like sound and the ‘Hurray!’ shouts declaimed by a male background choir in the chorus provide a weighty, statesman-like, meaning-laden musical framework for the song's overtly pejorative and racist language. This caricature of the politician speaking not all softly gains its effectiveness from the contrast between this tone and the implicit contradictions of the travestied images in the lyrics, such as ‘our peaceful Theodore’ ‘will wipe the Jap’.Footnote 59

In order to counter this pressure, the construction of the Canal needed to be officially legitimized, defended, and staged in a positive way. The cultural scene was harnessed for this aim, too. The following remarks examine how this negotiation of the Panama Canal between satire and propaganda took place in popular lyrics and music, and which images of Panama and the United States were conveyed in the process.

The dance song ‘The Panamala’ of 1914 (No. 25) seems to combine satire and exoticism. It presents an allegedly new dance, the Panamala, as a ‘better’ alternative to ‘fandango, ragtime, and tango’, as the lyrics say. The whole world could become both happier and better under the guidance of the United States if everyone danced the Panamala. This exaggerated message could also be read as satirizing the imperial, colonialist policies of the US government. The music is not so much interested in using genuine Panamanian dances such as the congo or the tamborito or even inventing a new one, but it adopts a ‘Tempo di Habanera’ and its characteristic rhythms draw on this famous Afro-Cuban dance (Example 1). Again, the Caribbean workers had brought the habanera to Panama as early as the nineteenth century, and its broad cultural dissemination means it is specific enough to function as typically Panamanian. It appears fundamentally Latin American and exotic. And it is precisely the supposed superficiality of this kind of exoticization that makes it so interesting. By only roughly approximating its subject, this exoticization reveals what its producers and recipients in the United States considered foreign yet familiar enough to fulfil the stereotype. According to Ralph P. Locke, exoticism is a ‘process of evoking a place (people, social milieu) that is perceived as different from home by the people who created the exoticist cultural product and by the people who receive it’.Footnote 60 Furthermore, the use of the habanera in ‘The Panamala’ goes beyond a merely superficial exoticization, revealing that we are dealing with the musical construction of an exotic Other, a construction that implicitly transcends Panama, referring to the manifold colonial interrelations and links across the entire Latin-Caribbean area. On the level of music history, we see these interrelations in the development of the habanera idiom from European models, especially counter-dances,Footnote 61 and on the level of politics they are evident in the recruitment of cheap labour from the Caribbean for hard planation work or large-scale projects such as the construction of canals.

Example 1 ‘The Panamala’ by Edward Madden and Gus Edwards (1914), bb. 1–8. Source: Frances G. Spencer Collection of American Popular Music.

The romantic song ‘In Dreamy Panama’ (No. 29), likewise published in 1914, goes in a similar direction. The lyrics also describe Panama as a place of longing, the tropical paradise as which Latin America was usually imagined:Footnote 62 Panama is constructed as a place where ‘tropical calm’ reigns, only ‘the melody of soft guitars is wafted thro' the trees on balmy breezes near and far’ and ‘a maiden just as fair as the blossom of a flower rare is waiting for me there’. This tropical Arcadia, filled with ‘Spanish’ guitar music, offers scope for a whole pool of projections of Otherness.Footnote 63 In particular, the Other as defined by gender comes to the fore here, a stereotype of tropical, vegetative femininity, the virgin as a rare flower associated with Panama. According to Fredrick B. Pike, the combination of nature and femininity, whether positively or negatively connoted, has been a constant stereotype in the US view of Latin America as a whole, representing a continuation of the US perspective on Indigenous North American cultures.Footnote 64 Accordingly, we can observe that the combination of the two topoi ‘Spanish / Latin guitars’ and ‘tropical vegetative femininity’ also occurs in several other songs, such as the abovementioned ‘Lola, the Fairest Daughter of Panama’. The country again is connected with a female identity (Lola) whose beauty is praised and compared with or even put above the beauty of flowers (‘To me fairer than even the Rose or Lily are’). When in ‘Lola’ the former colonial power Spain is mentioned (‘Bright is the smile as the noonday of Spain’), the music seems to take on a subtly ‘Spanish’ musical colouring, consisting of an accompaniment in 6/8 time that evokes guitar arpeggios and a melody enriched with embellishments that could easily be associated with a Spanish (or Latin) tinge.

In musical terms, these romantic songs do not exhibit any genuinely Panamanian characteristics either, instead once again referring to Latin America more generally through the guitar allusion or, as in the cases of both ‘In Dreamy Panama’ and ‘The Panamala’, in its guise as a tango. These very basic, not very specific musical elements, guitars and tango, seem to be sufficient indicators of the intended Otherness of Panama. Giving the United States's Other a higher degree of ‘exotic authenticity’Footnote 65 was obviously neither intended nor considered necessary. As a point of reference, Panama finally remains an object of orientalism, an unknown variable on the United States's part, a blank space in the game of projection and construction. It functions as a reservoir in the colonial ‘discourse about … the facts of “absence,” “lack,” and “non-being,” of identity and difference, of negativeness – in short, of nothingness’, as the postcolonial philosopher Achille Mbembe puts it.Footnote 66 Or, in the words of Pramod Nayar: ‘For the white man, the native is always the negative, primitive Other: the very opposite of what he and his culture stand for’.Footnote 67

Conclusion and avenues for future research

These examples reveal how the United States's political exercising of imperial power in Panama was accompanied, critically negotiated, and propagated by popular music in the early twentieth century. The musicological analysis has drawn on three key areas of postcolonial studies: first, the description of alterity; second, the analysis of power structures; and third, the deconstructivist view of the constructed nature of cultural attributions. These Panama-themed examples can be understood as a kind of prelude to the numerous ‘Latin Numbers’Footnote 68 that became a fixed part of the inventory of popular culture particularly from the 1930s onwards as part of a new (cultural) political orientation in the United States. The ‘good neighbour’ policy of Franklin D. Roosevelt's administration replaced the ‘big stick’ policy, heralding a new phase in the discovery of the ‘other America’. Numerous offices and committees were set up to promote friendly exchange with the United States's southern neighbours, such as the Division of Cultural Relations of the State Department, founded in 1938, or the Office for Coordination of Commercial and Cultural Relations (1940), which was absorbed into the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs in 1941. In 1939, Ben Cherrington, the head of the DCR, outlined the aims of his office as follows:

It is desired that the channels be opened for the free flow of ideas and cultural production from this country abroad and from the other nations to the United States. … It is anticipated, therefore, that the Division may also contribute effectively to a knowledge of foreign cultures among our own people. One of the activities of the Division is the fulfilment of the obligation which the United States has assumed under the Convention for the Promotion of Inter-American Cultural Relations, approved at the Buenos Aires Conference in 1936.Footnote 69

The aim of both offices ‘was to formulate and execute a program to increase hemispheric solidarity and further the spirit of inter-American cooperation’.Footnote 70 In musical terms, this was reflected in countless waves, each characterized by different idioms, images, ascriptions, and definitions of differences between Latin or Hispanic America and the United States, which for a long time understood itself as essentially white, Anglo-Saxon, and Protestant – and in many areas concerning the exercise of power continues to do so to the present day. These waves include the various dance waves (e.g., tango, conga, mambo, bossa nova, macarena) in various genres (e.g., jazz, dance music, songs, easy listening, film) as well as the musicals Panama Hattie, which Cole Porter composed for Broadway in 1940 (it takes place in the Panama Canal zone in the navy and nightclub milieu, taking exotic notions of Latin America and its musical idioms more or less for granted), Wonderful Town (Comden, Green, Bernstein; 1953) with its central conga scene, and West Side Story (Robbins, Sondheim, Laurents, Bernstein; 1957), which deals with the conflict between the United States and immigrants from Puerto Rico.

These booms in Latin numbers are striking in that the postcolonial cultural transfer they represent has not changed fundamentally since the beginning of the century, although it is now significantly more intense (especially with regard to the use of details borrowed from specific musical styles). We see a mixture of curious, open-minded fascination with what appears new and exciting, its appropriation and transformation, and ethnic and racist stereotyping, as Brian Eugenio Herrera has shown.Footnote 71 These Latin waves continue to boom to the present day, showing that it is no longer possible to construct a ‘US identity’ without integrating the United States's largest and fastest-growing ethnic minority: the Latinas/os/xs.Footnote 72

As a consequence, this perspective on music can be extended beyond the topic of ‘Panama’ to other musicological issues: to other musical genres such as concert music, to musical negotiations from the perspective of the colonized or oppressed,Footnote 73 to comparable settings in other regions of the world, to the interweaving of cultural and gender identities in musical practices and discourses, and much more besides. Today, when definitions of ‘Self’ and ‘Other’ are becoming ever more charged – and not only in the United States – this analytical view will allow us to gain a better understanding of music and its socio-cultural relevance.