The level of development of different countries determines the reliability of the available data record on twinning rates and whether studies about twinning have been done or not (Smits & Monden, Reference Smits and Monden2011). This issue is better known across the developed world with analyses of national representative data (e.g., Pison et al., Reference Pison, Monden and Smits2015). There is no background of analytical studies of twins in Uruguay, and therefore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first work focused on describing and analyzing Uruguayan twinning rates.

Twinning is rare among humans, but there is much variability among populations. In Asia and Latin America, on average, there are 6–9 deliveries of twins per 1000, but in Africa twin rates are above 18 deliveries per 1000 (Smits & Monden, Reference Smits and Monden2011). Several studies indicate that between 13 and 15 twin deliveries per 1000 are African Americans; however, in Europe, the rate varies between 10 and 20 deliveries per 1000 (Eriksson et al., Reference Eriksson, Abbott, Kostense and Fellman1995; Pison et al., Reference Pison, Couvert and Wasserman2004; Pison & D’Addato, Reference Pison and D’Addato2006; Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Schieve, Martin, Jeng and Macaluso2003).

Several studies show that certain demographic and socioeconomic factors, such as maternal age, mother’s educational level and income, influence the twinning rate (Beemsterboer et al., Reference Beemsterboer, Homburg, Gorter, Schats, Hompes and Lambalk2006; Bortolus et al., Reference Bortolus, Parazzini, Chatenoud, Benzi, Bianchi and Marini1999; Hoekstra et al., Reference Hoekstra, Zhao, Lambalk, Willemsen, Martin, Boomsma and Montgomery2008; Lummaa et al., Reference Lummaa, Haukioja, Lemmetyinen and Pikkola1998).

A family’s income determines the resources they can count on. An example of how resources affect twinning rates is a study by Lummaa et al. (Reference Lummaa, Haukioja, Lemmetyinen and Pikkola1998). Using data available from the pre-industrial (1752–1850) Finland, they compared the lifetime reproductive success of mothers of singletons and twins in the archipelago and mainland sites, two ecologically different areas. In the archipelago, the amount of food was relatively high and constant, whereas in poor mainland areas, crop failures and famines had been common. They found that on the archipelago, reproductive success was maximized by having twins, whereas on the mainland, reproductive success was maximized by having singletons, suggesting that a difference in twinning rate could be maintained by natural selection in historically relatively isolated human populations.

Twinning rates have changed around the world, and they have become greater since the 1980s, probably due to women delaying pregnancy until their 30s or 40s and the use of assisted reproduction techniques (ARTs). In the work carried out by Otta et al. (Reference Otta, Fernandes, Acquaviva, Lucci, Kiehl, Varella and Valentova2016) in Sao Paulo, Brazil, they found that the twin birth rate rose from over 10.19% to 13.33% from 2003 to 2014. Moreover, in agreement with a study carried out by Bortolus et al. (Reference Bortolus, Parazzini, Chatenoud, Benzi, Bianchi and Marini1999), they determined that the most predictive factor for the twin rate is maternal age. They also found that dizygotic twinning was strongly positively predicted by maternal age and, to a smaller degree, by time period (2003–2014), whereas monozygotic twinning increased marginally only with higher maternal age. In England, Wales, France, Sweden and the USA, there is an increase from one-quarter to one-third in the twin rate as maternal age increases (Bergh et al., Reference Bergh, Ericson, Hillensjö, Nygren and Wennerholm1999; Blondel et al., Reference Blondel, Norton, Du Mazaubrun and Breart2001; Blondel & Kaminski, Reference Blondel and Kaminski2002; Guignon-Back, Reference Guignon-Back1979; Sandra & Yip, Reference Sandra and Yip1995; Wood, Reference Wood1997). A similar result was found in Japan (Imaizumi, Reference Imaizumi1992).

Bulmer (Reference Bulmer1970) found that, even before ARTs, twinning rates increased by 300% between the ages of 15 and 37. Current findings strongly support the hypothesis that a higher chance of twin pregnancy in older mothers is due to an increased tendency toward multiple follicular development (Beemsterboer et al., Reference Beemsterboer, Homburg, Gorter, Schats, Hompes and Lambalk2006).

ARTs increase the likelihood of a multiple pregnancy (Wilcox et al., Reference Wilcox, Kiely, Melvin and Martin1996). The Latin American Network of Assisted Reproduction (REDLARA, 2015) reported in 2013 that transferring three or more embryos increases the likelihood of a multiple pregnancy (44.01% and 47.06%, respectively, for heterologous embryo transfers).

It is reasonable that twinning rates stay well below singleton rates because giving birth to twins or multiple offspring can be very costly for mothers’ energy, not only during gestation but also during the lactation period (Gomendio, Reference Gomendio, Pryce, Martin and Skuse1995). In addition, perinatal mortality is higher in twins (Olusanya, Reference Olusanya2011). In Latin America, twin mortality is almost as high as in Africa and is influenced by socioeconomic variables such as the social and economic development of the country and the parents’ educational level (Guo & Grummer-Strawn, Reference Guo and Grummer-Strawn1993).

Multiple pregnancy increases the risk of maternal and infant mortality, suggesting that humans are adapted to having only one offspring per gestation (Robson & Smith, Reference Robson and Smith2011). In nonhuman primates, multiple births rarely occur (Kishimoto et al., Reference Kishimoto, Ando, Tatara, Yamada, Konishi, Fukumori and Tomonaga2014; Matsumoto-Oda, Reference Matsumoto-Oda1995; Rosen, Reference Rosen1972). In chimpanzees, the monozygotic twinning rate (0.43%) is equal to the average human monozygotic rate (0.48%), but the dizygotic twinning rate (2.36%) is over twice the human average (Ely et al., Reference Ely, Frels, Howell, Izard, Keeling and Lee2006).

The present work, conducted from a human evolutionary perspective, intends to analyze different factors that could determine the twinning rate in Uruguay and to study its variation between 1999 and 2015. If Uruguay exhibits the same behavior as other countries reviewed in the literature, it would contribute to finding reliable predictors and establishing related public policies.

Materials and Methods

In this research, the twinning rates in Uruguay were analyzed over a period of 17 years (1999–2015). Uruguay is an emerging country located in the southeastern region of South America, bordered by Brazil to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the south and Argentina to the west, with an area of 176,215 sq km and a population of 3.4 million (Llambi et al., Reference Llambi, Rius, Carbajal, Carrasco and Cazulo2018; Winters & Martin, Reference Winters and Martin1995). Uruguay is divided into 19 departments, Montevideo being the capital of the country and having the highest population density (43%). The birth rate is lower in South America, but the life expectancy is higher, with an average of 72 years for men and 74 years for women (Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE], 2018). According to the World Bank, Uruguay stands out in Latin America for being an egalitarian society and for its high income level per capita, low level of inequality and poverty and the almost complete absence of extreme poverty. The Uruguayan society is one of the most developed societies in Latin America. The evolution of its development between 2005 and 2015 was significant, after the setback imposed by the economic crisis of 2002. Uruguay presents an open economy; its main exports are primary products, and there is a new trend in positioning service components (INE, 2018). The Uruguayan population is mainly of European descent, with negligible Native American or African contributions (Bertoni et al., Reference Bertoni, Jin, Chakraborty and Sans2005).

The birth data were collected from the website of the Ministry of Public Health, Uruguay, through the software REDATAM, created by Comisión Económica para América Latina y del Caribe (CELADE; http://colo1.msp.gub.uy/redbin/RpWebEngine.exe/Portal?BASE=VITAL_NAC&lang=es). The aim of this software is to transmit organized information of the associated countries. The variables used were multiples in pregnancy, place of maternal residence, maternal age and mother’s educational level. The data provided did not allow for zygocity determination. The database offers information for the 1995–2015 period, but it was decided to exclude the first 4 years because of incomplete information.

In order to establish an association between twinning rates and economic factors in the population (income per capita in the urban area and income in the household), the data were obtained from the INE’s website for the period 2001–2013, since these variables are defined specifically for that period of time.

The database did not include information about deaths, although it is recognized that it would be important to consider them as they would allow a better and more complete analysis of the Uruguayan population.

Due to the nature of the data, the different statistical analyses were carried out within the time periods the data allowed. The statistical software R (The R Project for Statistical Computing) was used.

Results

From the collected data, two groups of results are recognized: descriptive results that were ordered, graphed or tabulated to improve their understanding, but used directly from the source, and the results that were used as raw material for a set of statistical analyses, which allowed answering questions of greater complexity.

Descriptive Statistics

In the studied period, 18,297 twins were born out of a total of 834,673 births. The twin rate was calculated from the number of twin births according to the total deliveries in a ratio per 1000, and the triplet rate was calculated in a ratio per 10,000 (there is no data of triplets for the first 3 years; Table 1). Figure 1 displays temporal trends during the period of 1999–2015 for singleton and twin rates and 2002–2015 for triplet rate.

Table 1. Number of births per year classified according to the type of pregnancy, twin rate, triplet rate and hellin ratio (HR) values

Fig. 1. Temporal trends of singleton rates, twin rates and triplet rates in Uruguay.

Moreover, with twin and triplet rates, the Hellin ratio (HR) was estimated. This ratio is usually used in the literature (Fellman & Eriksson, Reference Fellman and Eriksson2009), and according to Hellin law, values greater than 1 represent an excess of triplets, while values below 1 indicate a deficit of triplets. The results indicate mathematically acceptable parameters, since the HR values are close to 1.

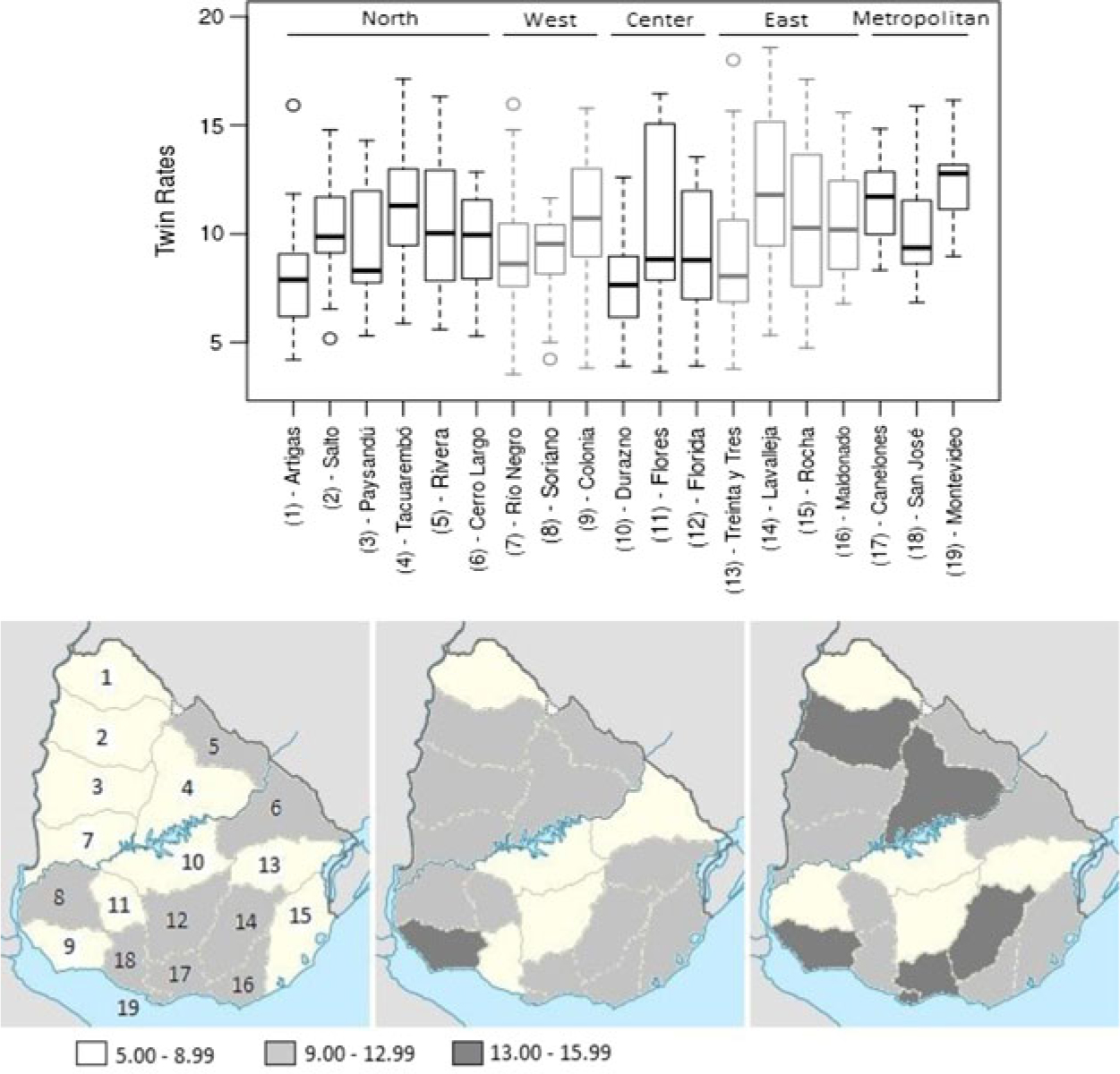

Figure 2 shows the boxplot for each department where it is possible to observe some important statistical values for data analysis such as minimum, maximum and quartiles. It is notable that Montevideo has the highest median and the smallest variability in comparison with other Uruguayan departments. Durazno has the lowest median, and Flores has the highest rate dispersion. It is worth noting that 43.7% of all twins were born in Montevideo. Figure 2 also shows the political division of Uruguay and the evolution through time periods of the medians for each department. Some departments of the North and Metropolitan regions exhibit an increase in medians over time.

Fig. 2. Boxplot of twinning rates by department from 1999 to 2015 and map of Uruguay showing the evolution of the medians through time periods (left: 1999–2004; middle: 2005–2010 and right: 2011–2015).

The literature establishes a positive correlation between maternal age and twinning (e.g., Beemsterboer et al., Reference Beemsterboer, Homburg, Gorter, Schats, Hompes and Lambalk2006; Cardoso-dos-Santos et al., Reference Cardoso-dos-Santos, Boquett, de Oliveira, Callegari-Jacques, Barbian, Sanseverino and Schuler-Faccini2018). Figure 3 shows that in Uruguay (1999–2015), the highest twinning rate (28.94%) was found in women aged 45 and older. This value is caused by a very small sample of twins (0.17% of all born twins) within this age group. It is possible that additional data could change the rates, making them similar to the results obtained in previous studies.

Fig. 3. Twinning rates per thousand deliveries according to maternal age.

Statistical Analysis

To determine the existence of an association between the twinning rate and the economic condition of the mother, a statistical correlation analysis was conducted, which included income per capita in the urban area and income in the household for the period 2001–2013. Figure 4 displays that in both variables the correlations were positive, but for several years statistically not significant.

Fig. 4. Correlation between income per capita and twinning rate and between household income and twinning rate.

It was possible to find a relationship between twinning birth rates and other socioeconomic variables, for example, the mother’s educational level. The analyzed period for this was 2011–2015. A chi-square test of independence was used, and the contingency table is shown in Table 2. The result of the test was χ2 = 16.25, for which the p value for a 95% confidence level is 9.4877. Therefore, the hypothesis of independence between the variables is rejected, indicating that there may be hints of a relationship between them. This result is mainly based on the great positive difference between the cases of twins that occurred and those expected under the hypothesis of independence in the case of mothers with at least 12 years of formal education.

Table 2. Statistical values resulting from the chi-square test of independence for 2011–2015, between the multiplicity in pregnancy and the educational level of the mother

As a first approach to the temporal analysis of birth rates throughout Uruguay, the number of twin births was compared between 1999 and 2015. The result of the comparison test of mean values was −1.76, which was significant at a 95% confidence level. However, when observing the data from each department for 1999–2015, there was an increased trend in the rate for some. The departments were grouped into political regions, and the time series were analyzed using autocorrelation functions and partial autocorrelation functions. The purpose of this analysis was to identify whether there is a relationship in the series themselves that give indications as to whether it is appropriate to establish randomness in the data or to model the series through autoregressive processes. The results were different in the regions that were analyzed. In three regions of the country (West, Center and East), twin rates show a random pattern, as indicated in Figure 5, in which the autocorrelation value for past lags falls within the confidence interval in the hypothesis test, which indicates that there is no relationship. On the other hand, in the two other regions (North and Metropolitan), there is an increasing trend in the number of twins over time. When analyzing the autocorrelation and partial autocorrelation functions in Figure 6, it is shown that the first lag of the series affects the behavior of this.

Fig. 5. Autocorrelation function and partial autocorrelation function for East, Center and West regions.

Fig. 6. Autocorrelation function and partial autocorrelation function for Metropolitan and North regions.

Discussion

The average rate of twins and triplets within the period analyzed (1999–2015) were 10.9% and 1.5% per 10,000 deliveries, respectively. It is observed that the HR fluctuated between values less than 1 and values greater than 1 without showing any trend in the evolution of the ratio.

The results about the age of the mother show that the variable twinning rate has a positive correlation that coincides with those found in other studies. According to Beemsterboer et al. (Reference Beemsterboer, Homburg, Gorter, Schats, Hompes and Lambalk2006), there is a greater probability of poliovulation in fertile women of advanced age. Also, there is a negative correlation between maternal age and twin mortality rates. Mothers who are aged 22 or younger have four times more risk of death of their twins than older mothers (Guo & Grummer-Strawn, Reference Guo and Grummer-Strawn1993). This result can also be associated with the application of ARTs because at a regional level, REDLARA (2015) reports that 56.97% of women who have had embryo transfers between 2000 and 2014 were older than 35 years.

Studying the results obtained by the application of these techniques is relevant for this work to analyze the data in an integrated way. The literature has established that ARTs increase the probability of multiple pregnancies (Derom et al., Reference Derom, Derom, Vlietinck, Maes and Van den Berghe1993; Pison et al., Reference Pison, Monden and Smits2015; Westergaard et al., Reference Westergaard, Wohlfahrt, Aaby and Melbye1997), especially due to the association that exists between this type of pregnancy and the number of embryos that are implanted (Schwarze et al., Reference Schwarze, Zegers-Hosghild and Galdames2010). REDLARA (2015) reports that in the period 2000–2013, almost 29% of the births were twins.

According to the literature, there is a positive link between the income of the mother and the twinning rate, and some indicators in the current study were found to show this trend. In the chi-square hypothesis test, it was observed that there are more cases than expected of twins with mothers with a high level of education. This relationship also suggests that economic factors affect the birth rate positively.

During the studied period in Uruguay, women who agreed to the use of ART had to show some purchasing power (probably associated with their economic conditions) since not all women could afford it at private clinics. In the results, an increased tendency of the rate of twins is shown in two regions of the country where centers of assisted reproduction are located. Although it is not possible to ensure that this is the cause of this trend, the results are intriguing.

With the objective of generating universal access to ARTs, Uruguay promulgated a law in November 2013 (Recuero, Reference Recuero2014) that regulates this. The National Resources Fund (FNR) is responsible for all or part of the expenses, depending on the income of the interested families. This research was carried out considering all the births in the period in which the law was not implemented. It remains to be seen whether the new legislation in Uruguay will have a significant impact on the number of multiple pregnancies, since the first baby assisted by this law was born in March 2016 (Nació Valentino, el primer bebé cuya gestación financió el FNR, 2016).

In conclusion, this study recognizes social, economic and demographic factors that influence the rate of twin births in Uruguay. The age of the mother is a relevant variable in the twin rate as well as certain factors related to the economic condition of the mother: her educational level and the use of ARTs. The results obtained are in agreement with previous studies.

Although the results achieved were satisfactory, certain restrictions were found in the analysis. Is a fact that the analyzed variables are correlated; it would be important to know the individual impact on the twinning rate when all of these are taken into account. However, the database used does not allow this analysis. Moreover, it is important to clarify that the results refer to twin births and do not include triplets or quadruplets. The decision was made based on the literature consulted and on the amount of data that was provided by the available databases. The datasets have some discontinuities and lack of information regarding the temporal analysis; moreover, it was impossible to identify or differentiate monozygotic from dizygotic births, which implies not knowing whether the temporal differences observed and the determinations of certain socioeconomic and demographic factors are relevant to the type of zygocity.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the members of Painel USP de Gêmeos, Brazil, and the Centro de Pesquisa Aplicada em Bem-Estar e Comportamento Humano FAPESP-Natura, Brazil.

Financial Support

The authors would like to thank the support of the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico CNPq 304740/2017-9 to EO).

Conflict of Interest

None.