1. INTRODUCTION

Defining and categorising sound installations raises several challenges given their wide range of approaches, practices and contexts. Furthermore, few sound artists identify with established disciplinary fields such as music or visual arts, and rather define themselves in-between fields (Canonne and Fryberger Reference Canonne and Fryberger2020). As such, it is difficult to compare and position sound installations within existing frameworks. However, many sound installations share common features including considerations of space and time. This article aims to propose a conceptual framework for describing and comparing sound installations based on similarities and differences in terms of design from a neutral point of view.

Sound installation is defined here as ‘a place, which has been articulated spatially with sounding elements for the purpose of listening over a long-time span’ (Bandt Reference Bandt2006: 353). Sound installations are closely related to an approach for sound art as an aesthetic category, allowing the introduction of any sound as potential material (LaBelle Reference LaBelle2006; Landy Reference Landy2007). Sound installation art emerged along with the development of sound art, performance and installation art as artistic mediums in the mid-century (LaBelle Reference LaBelle2006). According to Kihm (Reference Kihm2020), the appearance of sound installations as its own artistic field and its democratisation to broader audiences started in the 1980s. Since the 2000s, the number of gallery exhibitions devoted to sound art rapidly increased in galleries and museums (Džuverović Reference Džuverović2020).

Sound installations differ from more linear musical performances and concerts in multiple aspects, including their relationship with time and space. Temporally unlimited, they seldom have a clear beginning or an end, the duration of the engagement being defined by the visitor (Tittel Reference Tittel2009). On the other hand, space is a crucial element for sound installation design and composition. As the pioneer of sound installation art Max Neuhaus suggested, music differs from sound installations as in the latter sounds are ‘placed in space rather than in time’ (quoted in Ouzounian Reference Ouzounian2008: 115). Unlike a traditional concert situation with a predefined temporality and often dedicated spatial arrangements, listeners can mould their relationship with a sound installation over time and space and can experience it individually or collectively (Bandt Reference Bandt2006: 353). These specificities of sound installation require dedicated documentation frameworks.

Our research builds upon previous theoretical frameworks and formal reviews of sound art and other relevant sound-based practices. Landy established a thorough theoretical framework for describing sound-based artworks (Landy Reference Landy2007). Together with the Electro-Acoustic Resource Site project (EARS 2020), it aims at providing an extensive bibliographical tool for positioning various aspects of electroacoustic composition. Concerning sound installations specifically, Bandt reviewed various installations in Australia and proposed guidelines for public sound installation design (Bandt Reference Bandt2005). Following an inductive analysis across several publicly situated sound installations, Lacey proposed a conceptual framework for approaching sound installations (Lacey Reference Lacey2016). Brost proposed a documentation framework for sound in time-based media installation art (Brost Reference Brost2018). More recently, Goudarzi presented a taxonomy for situating participatory sound art (Goudarzi Reference Goudarzi2021) while Fraisse, Wanderley and Guastavino proposed a framework for describing interactive sound installations based on a systematic review of academic publications (Fraisse, Wanderley and Guastavino Reference Fraisse, Wanderley and Guastavino2021). Efforts to document sound installations are also present outside the academic realm. For instance, Cerwén created a detailed webpage listing various outdoor sound installations across the world (Cerwén Reference Cerwén2018). Furthermore, in a musical context, Birnbaum and colleagues defined a dimension space to characterise musical devices (Birnbaum, Fiebrink, Malloch and Wanderley Reference Birnbaum, Fiebrink, Malloch and Wanderley2005), and other frameworks have been proposed to situate collaborative musical devices and feedback musical systems (e.g., Blaine and Fels Reference Blaine and Fels2003; Hattwick and Wanderley Reference Hattwick and Wanderley2012; Sanfilippo and Valle Reference Sanfilippo and Valle2013; Morreale, De Angeli and Modhrain Reference Morreale, De Angeli and Modhrain2014). While these frameworks do not address sound installations directly, they describe interaction processes also found in the context of sound art and provide a basis for characterising interaction within the proposed taxonomy. Reconciling previous endeavours and extending the investigation to contemporary sound installations in Quebec, we developed a conceptual framework dedicated to an in-depth description of sound installations, in terms of the proposed categories of sound sources, sound design approaches and visiting modalities, each of which will be examined in the subsequent sections of this article.

The present work is part of the Sound Art Documentation: Spatial Audio and Significant Knowledge (SAD-SASK) research project. The documentation of new media art is a notoriously complex issue if we are to preserve it, where, according to Laurenson and Noordegraaf, a core challenge is to keep the balance ‘between allowing for evolution while still paying attention to the integrity of the work’, which impacts the model of documentation (Laurenson and Noordegraaf Reference Laurenson, Noordegraaf, Noordegraaf, Saba, Le Maïtre and Hediger2013: 285). The goal of the project is to investigate new means to document the sensory experience of sound installations with spatial audio technology and to identify the significant elements of these experiences for multiple stakeholders (sound artists, curators, conservators and sound engineers; see Boutard et al. Reference Boutard, Guastavino, Bernier, Gauthier, Fraisse, Giannini and Champagne2022 for further description). As part of the first phase of this project, we propose to reconcile and extend previous attempts, in relation to a visitor’s point of view, to systematically describe sound installations along multiple perspectives in the form of a taxonomy. Together with a review of contemporary sound installations in Quebec in a forthcoming publication (Boutard et al. Reference Boutard, Guastavino, Bernier, Gauthier, Fraisse, Giannini and Champagne2022), the taxonomy will serve as a conceptual framework to provide an overview of current practices and to inform the selection of a subset of sound installations for further investigation. This article is focused on a description of the framework and an illustration of its applications.

2. METHOD

2.1. Review of sound installations in Quebec

As part of the SAD-SASK project, we reviewed 75 contemporary sound installations deployed in Quebec, through written and audiovisual information publicly available on the web (Boutard et al. Reference Boutard, Guastavino, Bernier, Gauthier, Fraisse, Giannini and Champagne2022). Documentation included artists’ statements, personal web pages, galleries archives and promotional material. The aim of the review was to study a limited yet diverse selection of contrasting works to develop a taxonomy describing the many perspectives of sound installations relevant to the documentation process, with a focus on their relationship with space. The selection process relied on theoretical sampling from grounded theory: works were retrieved according to emerging categories of the taxonomy to cover a wide range of practices.

We used the following inclusion criteria: sounds installations presented in Quebec over the past ten years, with publicly available documentation, in the form of textual information, pictures, audio excerpts and/or video clips. The review of practices is presented and described in detail in (Boutard et al. Reference Boutard, Guastavino, Bernier, Gauthier, Fraisse, Giannini and Champagne2022). We report here on a taxonomy for describing sound installations, used as a conceptual framework along with the review to account for the diversity of practices.

2.2. Analysis method

The conception of the present conceptual framework was two-sided and involved a combination of deductive and inductive analyses. The deductive analysis was informed by the literature review on conceptual and theoretical frameworks related to sound art and sound installations presented in the introduction. The inductive analysis was based on a review of contemporary sound art installations in Quebec in the context of the SAD-SASK project (Boutard et al. Reference Boutard, Guastavino, Bernier, Gauthier, Fraisse, Giannini and Champagne2022). While the taxonomy builds upon existing theoretical and conceptual frameworks and guidelines on sound art and sound installations, new perspectives emerged from the inductive analysis of the documents. These additional features were integrated to provide a comprehensive framework for describing significant features from a visitor’s point of view, such as those related to visiting modalities and visual aspects.

In the first phase, although research results were shared regularly, two independent taxonomies were developed by the first two authors from the deductive and inductive analyses, respectively. In an attempt to identify relevant categories for spatial audio documentation, aspects that may influence a visitor’s experience of the works were considered. How does one physically access the work? Are there visible aspects that indicate the presence of the work? Do the sound sources envelop the visitor, or is it more of a frontal auditory display? The coding process started with a small set of installations and categories defined by the research members. For each of these categories, information regarding the associated installation was coded. As the works went through review, new categories were added to the taxonomy to account for the features of each installation. New installations were selected and added to cover a wide range of practices and reach a stable coding scheme. In a second phase, a single shared taxonomy was created, integrating the results of the inductive method into the analytical framework of the deductive approach. The resulting merged taxonomy was reviewed and refined with the researchers of SAD-SASK and then used to re-categorise systematically all the works previously coded inductively.

3. A TAXONOMY FOR SITUATING SOUND INSTALLATIONS

A taxonomy in the sense of Bailey’s definition was elaborated to situate sound installations (Bailey Reference Bailey1994), with an emphasis on the visitor’s perspective, as opposed to a conservation perspective. As such, it does not emphasise work production processes such as sound recording and medium (Brost Reference Brost2018) or a thorough analysis of the works (Landy Reference Landy2007). Rather, it focuses on the documentation of installations from the point of view of the visitor by identifying features that shape the relationship with the sound installation. While the taxonomy derives from the identification of features that appear significant from the visitor’s stance, we did not make inferences on the way works may be received or on the creative process. Rather, the taxonomy provides a neutral reference point for further analysis and documentation. The taxonomy was developed in the context of the SAD-SASK project, in which the documentation process is characterised by the use of spatial audio recording and the absence of visual materials. Particular attention is therefore given to aspects related to spatial auditory perception, while information related to visual aspects remains concise.

The taxonomy is ordered hierarchically, from general to specific. Specific categories were first identified and later grouped into more general, broader themes. At the more abstract level of the taxonomy, perspectives relate to general aspects for enduring sound installations, such as sound design approaches or visiting modalities. At an intermediary level of abstraction, themes situate specific aspects from the perspectives in which they are embedded, such as material and process related to sound design approaches. At the most concrete level, taxa describe specific features and applications of the installation, such as the use of sonification. Most of the taxa are not mutually exclusive, meaning that several taxa from a single theme can be associated with a given work.

An overview of the taxonomy’s perspectives and themes is provided in the following sections. For each perspective, a hypertree visualisation is proposed to represent the various taxa and their hierarchical relation. On these visualisations, the hierarchy between sections is emphasised by the colour of the sections from black (top-level categories, perspectives) to white (bottom-level categories, taxa) as well as the size of the link between nodes, proportional to the hierarchy level. Nodes are of different sizes only to provide adequate room for the categories’ names. A detailed definition of every taxon is provided in the Appendix.

3.1. Sound Source

Sound Source relates to a sound installation’s sound source(s), as shown in Figure 1. It is inspired by Lacey’s three approaches to creating sound installations (Lacey Reference Lacey2016): electro-acoustic (loudspeakers/playback), resonant (use of resonant properties of tubes/pipes or structural vibrations; not architecturalFootnote 1 ) and elemental (installations driven by the elements, or those that use elements to generate sounds such as aeolian harps). However, speakers are considered in a separate taxon due to their common occurrence.

Figure 1. Sound Sources.

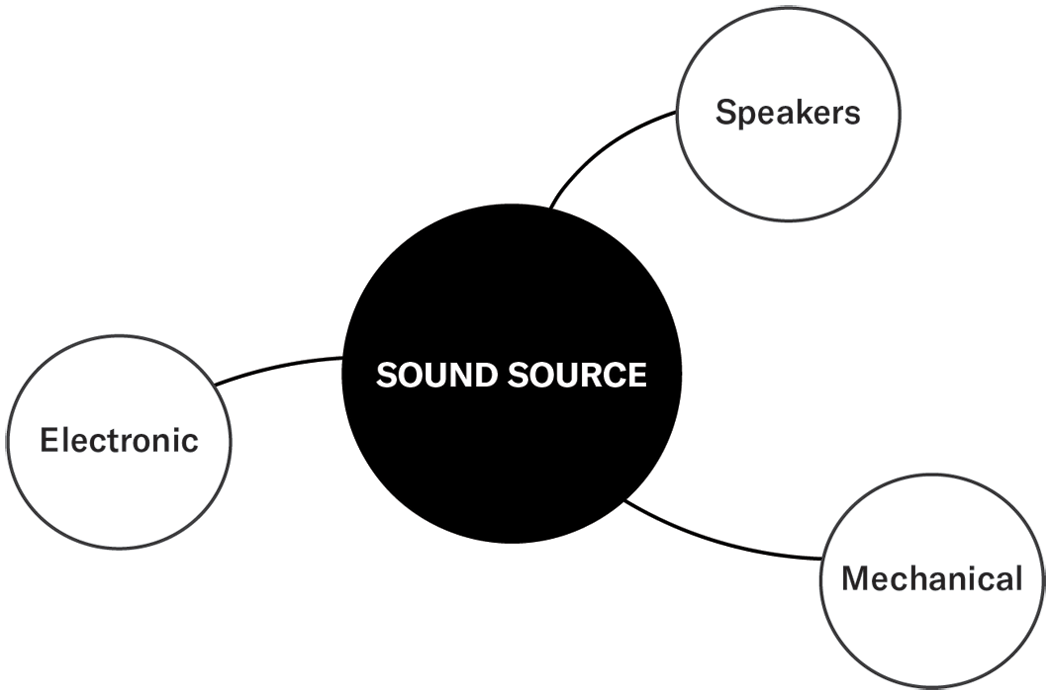

3.2. Sound Design Approaches

The Sound Design Approaches perspective relates to all the contextual and system design features related to the sound environment generated or transformed by the installation (Figure 2). It concerns both the generated sound contents in terms of materials and involved processes and the diffusion features such as spatialisation and site-specific imperatives.

Figure 2. Sound Design Approaches.

3.2.1. Material and Process

While Material refers to the source and properties of the contents that constitute the broadcasted sound extracts, Process refers to all the processes involved by the installation to generate or alter sound contents. Most of the taxa related to Material and Process come from Landy’s framework for sound-based Art and associated Electro Acoustic Resource Site project (Landy Reference Landy2007; EARS 2020). Across this typology, a division of sound objects through an abstract/referential dichotomy is proposed: abstract sounds cannot be ascribed to any real or imaginary provenance whereas referential sounds are recorded sounds that ‘suggest or at least do not hide the source to which they belong’ (EARS 2020). Pre-existing materials are also included in the EARS typology as samples, as well as sonification. It also occurs to creators to make use of recordings from the surrounding environment (Tittel Reference Tittel2009), artificial feedback generation (van Eck Reference van Eck2013), or almost unnoticeable sounds (Roads Reference Roads2004).

3.2.2. Spatialisation

With the development of sound installations and the free motion of participants, space became the centre of perception, and installations required a contextualisation that goes beyond the mere spatial characteristics such as acoustics or architectonics (Klein Reference Klein2009; Kihm Reference Kihm2020). Hence, sound artists and designers carefully consider the intersection between space and time through the intentional placement of the sound sources, and spatialisation features are compulsory for situating sound installations (Bandt Reference Bandt2006). Spatialisation relates to the number, position, orientation and diffusion parameters of an installation’s sound sources. Motion and paths accessible to a visitor are described in the Visiting Modalities perspective.

3.2.3. Site-specific

Unlike conventional music that can theoretically be displayed everywhere or at least at any performance hall, sound installations are often significantly connected to the site on which they are standing, and their design is commonly considered with respect to the architectonic, sociological, historical and other contextual information, gathered under the term site-specificity (Tittel Reference Tittel2009), or situations (Groth and Samson Reference Groth and Samson2017). Overall, it is reasonable to claim that the musicality of an urban sound installation emerges from a creator’s thought to form a site-specific listening relationship, such that a sound installation feels like a natural expression of the site. Further, architectural understandings can be pervasive in the approach to sound art and urban design (Lacey Reference Lacey2016).

The present theme combines contextual features related to those aspects. Of course, the relation to the site is radically different between a publicly situated sound installation and a gallery installation, and most of the present theme’s taxa are not pertinent for gallery installations. For example, Lacey evokes the imperative for an urban installation to be non-disruptive, as well as the depersonalisation of the sound artist, both features that may not apply in museum settings (Lacey Reference Lacey2016), although it is argued that the requirement for non-disruptivity may also be applied in gallery settings (Seay Reference Seay2014).

Livingston introduced a taxonomic division of introduced sounds that are borrowed in the present taxonomy: integrated/site-specific/background where added sounds subtly merge with the existing sound environment, versus oppositional/borrowed/foreground where added sounds clearly distinguish themselves from the sound environment (Livingston Reference Livingston2016).

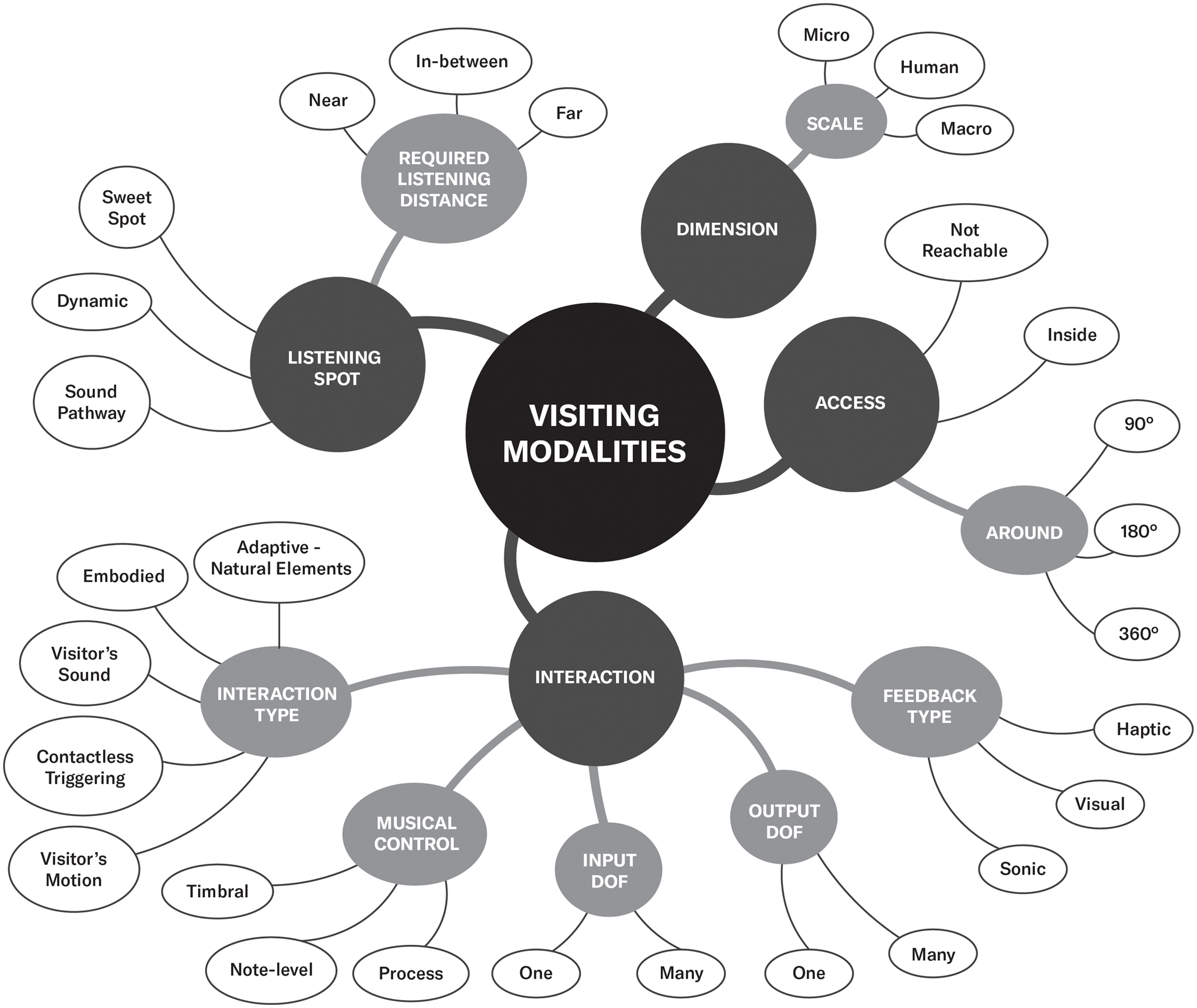

3.3. Visiting Modalities

Unlike other listening experiences, which are usually from a fixed point, sound installations invite visitors to move in and around them and to define their own path of listening (Bandt Reference Bandt2006). Installations may additionally require interaction with visitors, which may significantly affect their experience (Mugnier and Ho Reference Mugnier and Ho2012; Fraisse et al. Reference Fraisse, Wanderley and Guastavino2021). Overall, cases range from situations in which visitors have frontal access to the work to situations in which the visitor can walk around the work or enter inside it. The Visiting Modalities perspective aims at situating this relationship between a visitor and a sound installation, through themes related to spatial features and physical accessibility (access, dimension and listening position) and interaction (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Visiting Modalities.

3.3.1. Dimension, Access and Listening Spot

All three themes, Dimension, Access and Listening Spot, relate to the spatial relationship a visitor can mould with an installation through its own motion. Dimension refers to the scale of an installation relative to the human scale. Access relates to the modalities of approach to the work, whether inside or around. The Listening Spot refers to the available motion to the visitor, corresponding either to a specified pathway, an ideal, or a dynamic listening spot, as well as the required distance for the installation to be audible, that is, the minimal distance at which the listener can hear it as intended by its creator. Notably, Bandt’s introduced notion of sound pathway is applied where visitors are intended to follow a specific path (Bandt Reference Bandt2006).

3.3.2. Interaction

In museal settings, installations can sometimes require interaction with visitors to generate audio, visual or even haptic feedback. Interaction is understood here as ‘a reciprocal action between several actors of the same system … resulting in a modification of the state of the implied actors’ (Mugnier and Ho Reference Mugnier and Ho2012). To classify those interactive installations, the typology includes a categorisation derived from Birnbaum’s dimension space for musical devices (Birnbaum et al. Reference Birnbaum, Fiebrink, Malloch and Wanderley2005) and is also informed by a theoretical framework proposed by Fraisse and colleagues for describing interactive sound installations (Fraisse et al. Reference Fraisse, Wanderley and Guastavino2021). It aims both at characterising the type of interaction and control a user or the surrounding environment can have as well as the type of feedback provided by the installation.

3.4. Visual Aspects

Sound installations situate themselves at the intersection of artistic practices by bridging the visual arts with the sonic arts (LaBelle Reference LaBelle2006). As such, and while the present taxonomy is focused on sound, the perspective Visual Aspects is proposed to situate a sound installation according to its visible properties (Figure 4). Intervention Visibility describes the extent to which an installation is made visible to the visitor. Visibility relates to the amount of luminance that is available to the visitor. Finally, Static depicts the presence of still visual features, and Dynamic the presence of evolving visual features.

Figure 4. Visual Aspects.

4. COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF SELECTED WORKS

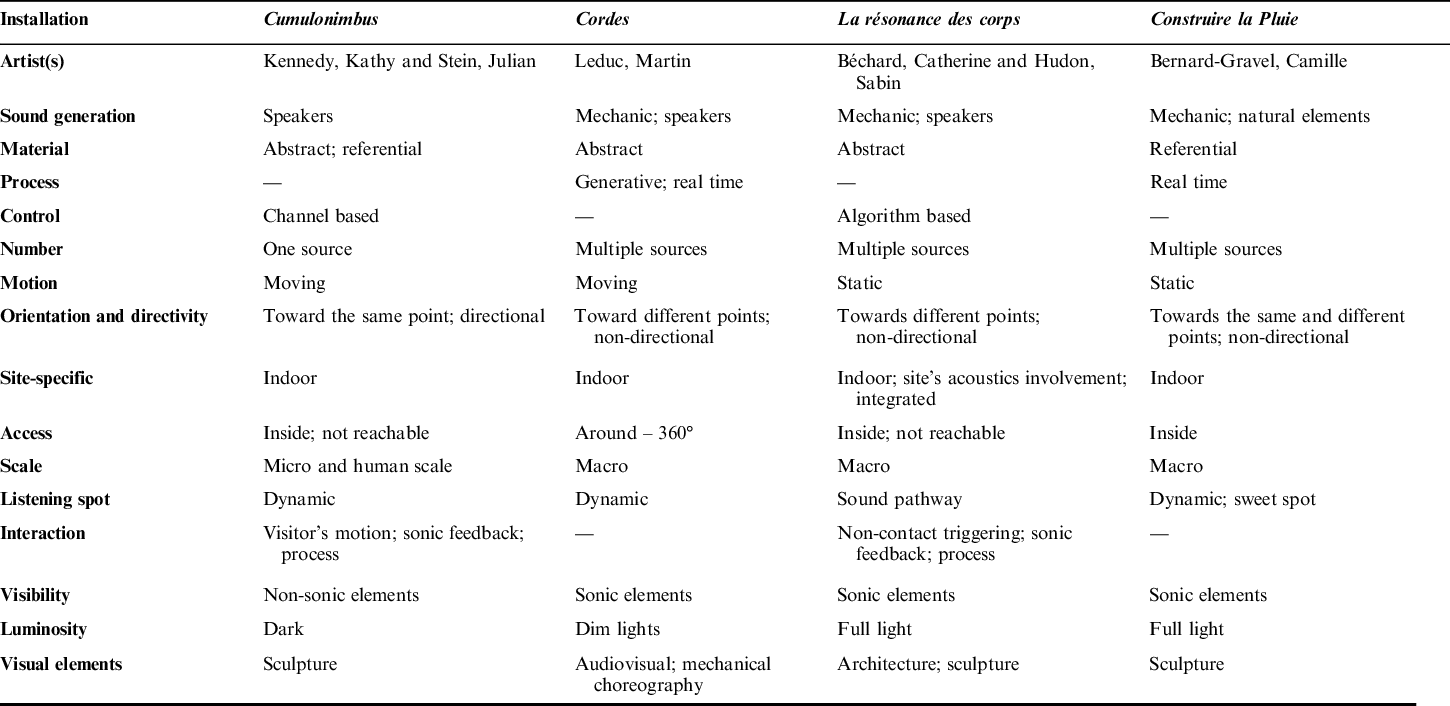

The proposed taxonomy was designed as a versatile tool for sound installation description and comparison so that the greatest diversity of installations could be embedded into it. To illustrate its potential benefits, four installations selected from the SAD-SASK project’s review will be described along with a sample of selected themes for each perspective. The aforementioned description is presented in Table 1 and described in the following section.

Table 1. Comparative analysis of selected works across the taxonomy

Note: — = non-applicable taxa.

Cumulonimbus is a sound installation designed by Kathy Kennedy and Julian Stein (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2021). It consists of an interactive environment in which visitors are followed by a rotative, ultrasonic speaker (Figure 5). The composition is based on a background layer of rain and wind on top of which voices whispering excerpts from Shakespeare’s Macbeth are added. The installation includes two sculptures: bowls filled with money and water.

Figure 5. Cumulonimbus. Photo courtesy of Kathy Kennedy.

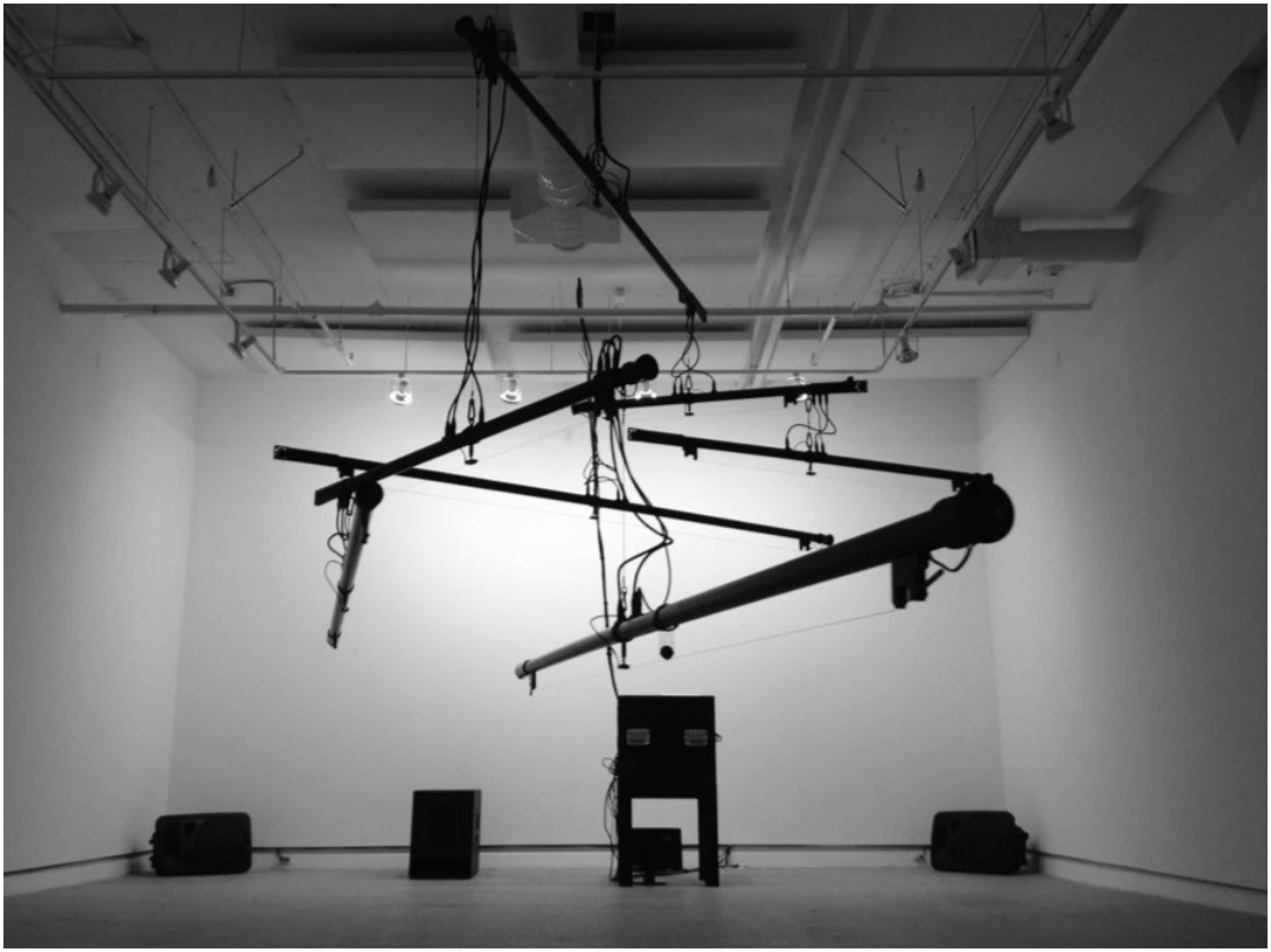

Cordes is a ‘kinetic instrument’ created by Martin Leduc (Mongeau Reference Mongeau2015). A mobile hangs in the space, based on multiple cylinders on the azimuth plane (Figure 6). On each cylinder is stretched a string, generating sounds thanks to a magnetic field controlled in a pseudo-random way by a stochastic algorithm. The cylinders’ motion is controlled by remote fans. Cordes is thought of as a continuously evolving sound installation, such that its sonic content is perpetually renewed in spite of its stochastic nature (Poirier Reference Poirier2016).

Figure 6. Cordes. Photo courtesy of Martin Leduc.

La résonance des corps is an in situ sound installation embedded into the steeple of Saint-Sauveur Church at the Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM) in Quebec, Canada (Béchard and Hudon Reference Béchard and Hudon2016). It consists of three aluminum sculptures that function as speakers, scattered throughout the height of the church’s bell tower (Figure 7). Vibro-tactile transducers transmit the composition through aluminum plates, creating an immersive sound environment thanks to the acoustics of the place. Visitors can move through sound and space within a dedicated pathway inside the steeple.

Figure 7. La résonance des corps. Photo courtesy of Béchard Hudon.

Construire la pluie is a gallery installation that aims at reproducing the sound of the rain, created by Camille Bernard-Gravel (Fortin Reference Fortin2016). A first room is a wide and tall hall containing a series of containers dripping water on successive pierced buckets (Figure 8). The multiple buckets in addition to the stochastic nature of the falling droplets create the first layer of a sound environment mimicking the rain. Inside a second, small room, a plastic bag in permanent rotation is embedded into a soundproof box. The sound contents generated by the two rooms are recorded and mixed together to recreate a rain environment, which can be listened to with the help of headphones made available to visitors.

Figure 8. Construire la pluie. Photo courtesy of Camille Bernard-Gravel.

While Cumulonimbus solely makes use of speakers, the three other installations combine two sound sources including speakers, mechanic sources (resonating strings in Cordes; structural vibrations in La résonance des corps; the sound of a plastic bag in Construire la pluie), and natural elements (falling water droplets in Construire la pluie).

A great variety of sound design approaches can be observed across all four installations. Regarding the involved material, all can be described across the abstract/referential dichotomy. Interestingly, Construire la pluie reproduces sounds referring to the rain, consisting as such in referential sounds of a synthetic origin (EARS 2020). Concerning the involved processes, both Cordes and Construire la pluie produce sound content in real-time, while Cordes involves a generative algorithm. About spatialisation, Cumulonimbus makes use of a single sound source while all others combine multiple sound sources. Cumulonimbus and Cordes involve moving sound source(s) while La résonance des corps and Construire la pluie dispose of static sources. Cumulonimbus makes use of a directional sound source that is oriented towards a unique, moving point (the visitor). All three other installations are diffusing sound towards multiple directions and do not imply any directional source. Regarding site-specificity, only La résonance des corps is a site-specific installation, being embedded in a church while exploiting its acoustical properties. The three other works are gallery installations.

The four installations are equally diverse while sharing similarities regarding the Visiting Modalities. Cordes can be accessed by moving around the installation while all three others require the visitor to get inside the installations. Cumulonimbus is of a relatively small scale compared with the others that are beyond the human scale. All four installations allow the visitor to move while listening to them. However, La résonance des corps implies a specific path, a sound pathway that must be undertaken by the visitor(s) to appreciate it. Ultimately, both Cumulonimbus and La résonance des corps take use of user interaction: the sound source in Cumulonimbus follows the visitor by capturing its motion while La résonance des corps is triggered by approaching visitors through a proximity sensor.

Concerning the Visual Aspects, Cumulonimbus disposes of non-sonic sculptures that are visible to the visitor(s) in a dark environment while all others allow the visitor(s) to see the sound sources in the form of sculptures with full light in La résonance des corps and Construire la pluie, and of a mechanical choreography with dim lights in Cordes. Cordes implies additional audiovisual content (video projections), while La résonance des corps is embedded into the surrounding church’s architecture.

As shown in Table 1, the proposed taxonomy allows for the identification of similarities and differences along different perspectives. It further highlights sound installations specificities such as, in the preceding examples, the peculiar interaction for Cumulonimbus and the site-specific configuration of La résonance des corps. This taxonomy can inform both researchers and artists in providing grounds for the identification of trends (e.g., all the preceding installations are located indoors and use of speakers and/or mechanic sound sources), and the exploration of a collection of works along multiple complementary perspectives, including aspects relevant to the visitor’s experience.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Based on a review of 75 contemporary sound installations in Quebec, we propose a taxonomy to describe and establish comparison across sound installations with an emphasis on the visitor’s perspective. Given the wide range of practices covered (see Boutard et al. Reference Boutard, Guastavino, Bernier, Gauthier, Fraisse, Giannini and Champagne2022 for further analysis), we believe that the taxonomy would be transferable, to some extent, to other geographical contexts. The perspectives should provide insights into comparative studies of sound installations in a variety of contexts, ranging from sound installations in public spaces to interactive multimedia environments in galleries.

The primary purpose of the present taxonomy is documentation, as it is meant to help identify significant properties, common practice and trends across sound installations’ design. The taxonomy remains as neutral as possible to allow for the identification and screening of works without a prior evaluation of the impact they may have on an audience nor on the rationale that led to their creation. It relies on a descriptive categorisation of sound installations’ features based on a neutral analysis of musical works, rather than poietic or esthesic analyses (Nattiez Reference Nattiez1974), that are beyond the scope of this article. Indeed, the present framework is not oriented towards a detailed analysis of the works, nor does it cover technical details (Landy Reference Landy2007; Malloch and Wanderley Reference Malloch, Wanderley, Lesaffre, Leman and Maes2017), or necessary information for curation such as sound production parameters and support (Brost Reference Brost2018). Instead, it focuses on documenting the installation from the underexplored yet critical perspective of the visitor. Documentation frameworks designed for curators such as Brost’s typically focus on technical specification and artistic intent (Brost Reference Brost2018). Here we propose instead to situate all features that may be relevant from a visitor’s point of view, regardless of situational and technical parameters. This approach allows a user of the taxonomy to freely explore themes of interest to them, within a broad range of perspectives. Further and as discussed earlier in the introduction, sound installations often have a peculiar relation with time, some of which may significantly evolve across time (such as environmentally adaptative installations, see, for instance, Paine Reference Paine2003). The taxonomy, however, only allows for the establishment of a fixed snapshot of installations and cannot account for their temporal evolutions. Ultimately, and given the focus on spatial audio, the description of the visual features is only used to contextualise the works considered. Future directions could extend this line of research to the audiovisual experience of the visitor.

The present work is grounded in the analysis of artists’ statements, auto-documentations, and alternative media that come from practical documentation. As such, it is a logical extension of the framework proposed by Fraisse, Wanderley and Guastavino based on a review of 195 sound installations presented in academic publications (Fraisse et al. Reference Fraisse, Wanderley and Guastavino2021). Together, these frameworks represent a broad range of practices and contexts, within and outside of the academic realm, in Quebec and beyond. The taxonomy should also be of interest to sound artists to stimulate discussions around sound installation practices.

The comparison of sound installations along the different perspectives of the taxonomy will be used to identify contrasting works for further investigation in a second phase of the SAD-SASK project, which will involve perceptual evaluations of sound installations. Beyond this project, the proposed framework represents a useful tool to describe and compare sound installations across meaningful perspectives from a visitor’s point of view. Indeed, this framework could be applied to other types of works in other contexts. For example, it could help consolidate previous lists of installations, such as the one compiled by Cerwén (Reference Cerwén2018), in an attempt to create a large-scale searchable database of sound installations. Future research is needed to develop visualisation tools for the taxonomy to facilitate database navigation and searching. Such a tool would allow researchers and artists to identify installations through associated keywords, to find related installations and to compare them along the multiple perspectives of the framework.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Julien Champagne for his help and participation in the elaboration of the taxonomy, as well as the members of the SAD-SASK project, Philippe-Aubert Gauthier and Nicolas Bernier, for their valuable input and feedback on the taxonomy. The SAD-SASK project is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). All the authors are affiliated with the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Music Media and Technology (CIRMMT), Montreal, Canada.

Appendix

Table App1 lists all taxa from the taxonomy.

Table App1. Description of the taxonomy: taxa definitions