Introduction: Assessing Value from a Societal Perspective

In assessing value of new medicines to guide decisions about reimbursement and funding which ultimately affect resource allocation, it is important to remember that individuals have varying preferences for health technologies just as they do for other economic goods (Reference Garrison, Pauly, Willke and Neumann1) and will, thus, vary in their valuations. Current assessments of value by health technology assessment (HTA) organizations tend to take a “healthcare sector” perspective, and in doing so, may not comprehensively capture all treatment benefits and costs that matter to patients and their families (Reference Garrison, Mansley, Abbott, Bresnahan, Hay and Smeeding2;Reference Kim, Silver, Kunst, Cohen, Ollendorf and Neumann3).

HTA agencies recognize that this perspective can be narrow. The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER), and the U.S. Second Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine all recommend conducting a parallel “societal” perspective for “reference case” cost-effectiveness analyses (CEAs) for improved comprehensiveness, consistency, and comparability (4–Reference Gold, Siegel, Russell and Weinstein6). A broader societal perspective ideally considers time costs, social opportunity costs of resources, and community preferences (Reference Garrison, Mansley, Abbott, Bresnahan, Hay and Smeeding2). In a CEA conducted from a societal perspective, “the analyst considers all parties affected by the intervention and counts all significant outcomes and costs that flow from it, regardless of who experiences the outcomes or bears the cost” (Reference Sanders, Neumann, Basu, Brock, Feeny and Krahn7).

In economic evaluation of health technologies, value is often assessed using CEA to measure and compare incremental costs and benefits of these health innovations; the comparative efficacy, safety, and costs between two interventions are assessed to inform reimbursement decisions. Incremental health benefits are often quantified in terms of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) that summarize both the expected quantity and quality of life gained from the innovation. The net cost impact reflects the price of the innovation minus any cost savings, referred to as “cost-offsets.” Unfortunately, QALYs may “capture only a subset of benefits … and neglect numerous alternative aspects of benefits that should also be considered” (Reference Oortwijn, Sampietro-Colom and Habens8). Here, we consider the omission of benefits and disutility to family members, also referred to as “family spillovers” by the U.S. Second Panel (Reference Sanders, Neumann, Basu, Brock, Feeny and Krahn7), in current evaluations of Alzheimer's Disease (AD) medications as a case example.

Value Assessment and Economic Impact

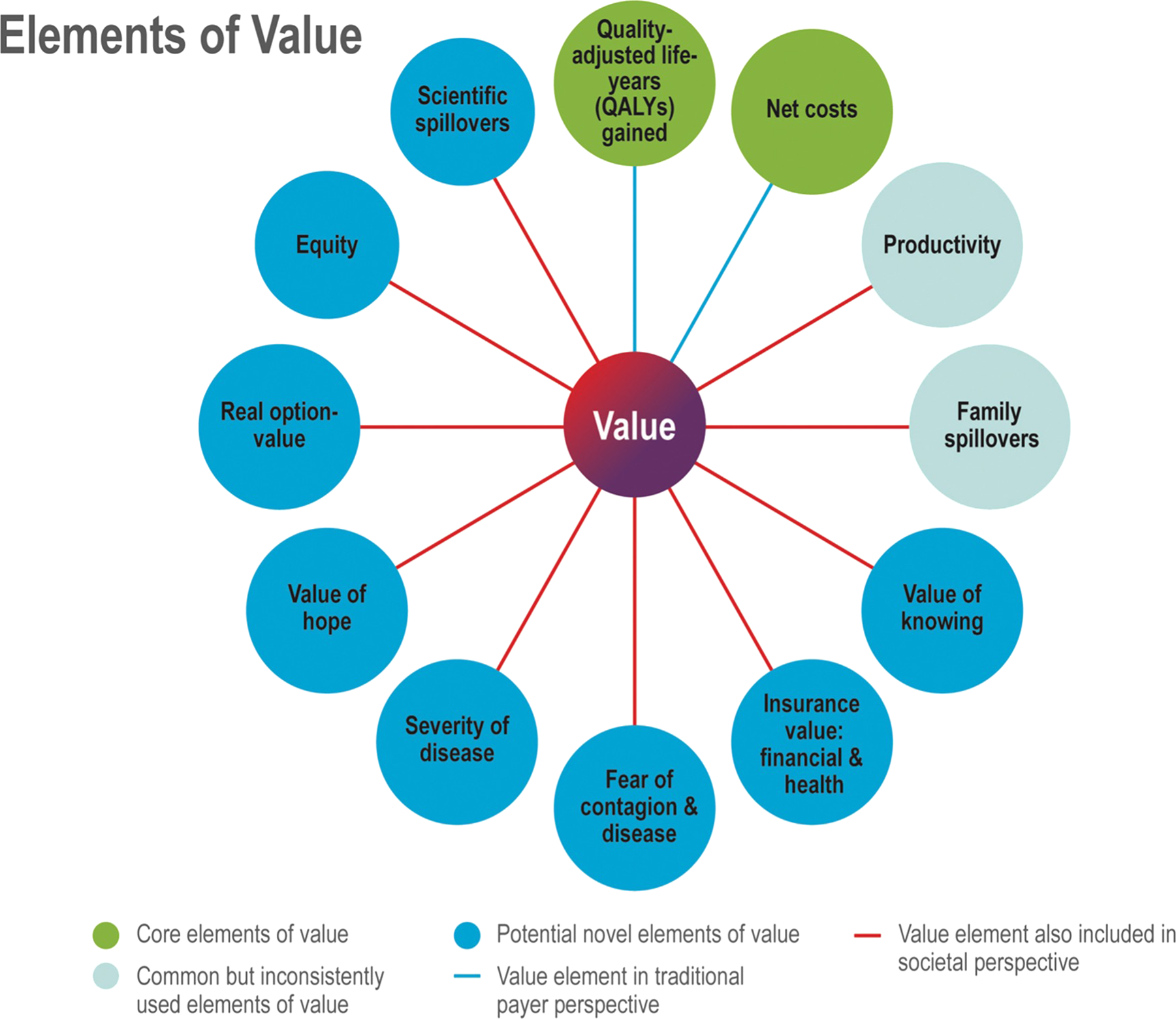

In support of efforts to holistically assess the value of health innovations, specialty societies, policy analysts, health economists, and other stakeholders have proposed several broadened value frameworks both within and across various therapeutic areas and with special attention to pharmaceuticals (Reference Oortwijn, Sampietro-Colom and Habens8;Reference Neumann, Willke and Garrison9). A recent ISPOR task force comprehensively reviewed several value frameworks and identified “elements of value”—both conventional and novel—that might come into play in the decision to add coverage of a new technology in a health plan or to add a new drug to a plan formulary. The task force categorized these elements and presented them as a “Value Flower” depicted in Figure 1 (Reference Lakdawalla, Doshi, Garrison, Phelps, Basu and Danzon10;Reference Baumgart, Garrison, Hayek and Leibman11). The elements in green, light blue, and dark blue, respectively, represent core, common, and novel value concepts. The blue lines indicate elements of value typically incorporated in evaluations from the traditional payer or healthcare sector perspectives, whereas the red lines indicate those included in the broader societal perspective. Family spillovers, an element of value evidently critical in AD, is noted as a common element typically lacking in CEAs from the payer or health plan perspectives (Reference Lin, D'Cruz, Leech, Neumann, Aigbogun and Oberdhan12).

Figure 1. The adapted ISPOR value flower (Reference Lakdawalla, Doshi, Garrison, Phelps, Basu and Danzon10;Reference Baumgart, Garrison, Hayek and Leibman11).

The Economic Burden of Alzheimer's Disease

Current value assessments of novel medicines—particularly, for inclusion in a health plan's benefit package—tend to focus on the incremental impact on the individual patient level—and for a typical patient with a specific health condition. This is understandable given that the supporting clinical trials are powered to assess clinical efficacy in patients with the condition. However, health plans and other decision makers also seek a more comprehensive view of impact, and manufacturers often prepare a companion study of existing or predicted “economic burden” of disease performed in parallel with such value assessments to estimate the total burden as well as the “unmet need” of a particular disease to society. Although widely used, the term “economic burden” is not always consistently defined or measured. “Cost of illness” (COI) (Reference Rice13) or “burden of disease” (BOD) (14;15) are related metrics.

For our purposes, “economic burden” will include direct medical costs and nonmedical costs as well as indirect costs. In other words, the health impacts (lost life-years or impaired quality of life) and time costs are also converted to monetary terms.

The 2015 World Alzheimer Report (WAR) (Reference Prince, Wimo, Guerchet, Ali, Wu and Prina16) estimated that the total worldwide economic burden of dementia was USD 818 billion in 2015, representing over 46 million patients. Direct medical costs including outpatient costs, expenses for health care, and medications accounted for 19.5 percent. Direct social care costs consisting of paid professional home care and residential or nursing home care accounted for 40.1 percent. Costs of informal care valued using an “opportunity cost approach” incorporating time and productivity loss based on the average hourly wage of each country accounted for 40.4 percent of the total costs.

In a recent U.S. study, the Alzheimer's Association used data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS), Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and the Congressional Budget Office to estimate that the costs of care for 6.2 million Americans with AD, excluding costs of unpaid informal care, were USD 267 billion in 2020 (17). The study also incorporated data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey, the National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC)/AARP, and the US Census Bureau as inputs into their U.S. caregiving model, estimating that 11.2 million unpaid dementia caregivers provided an estimated 15.3 billion hours of care in 2020; and using state minimum wages to calculate opportunity costs, the net economic value of unpaid caregiving in 2020 was estimated to be USD 256.7 billion (18). Combined, the total U.S. economic burden of dementia in 2020 was estimated to be USD 523.7 billion; this equates to almost USD 85,000 per patient with AD.

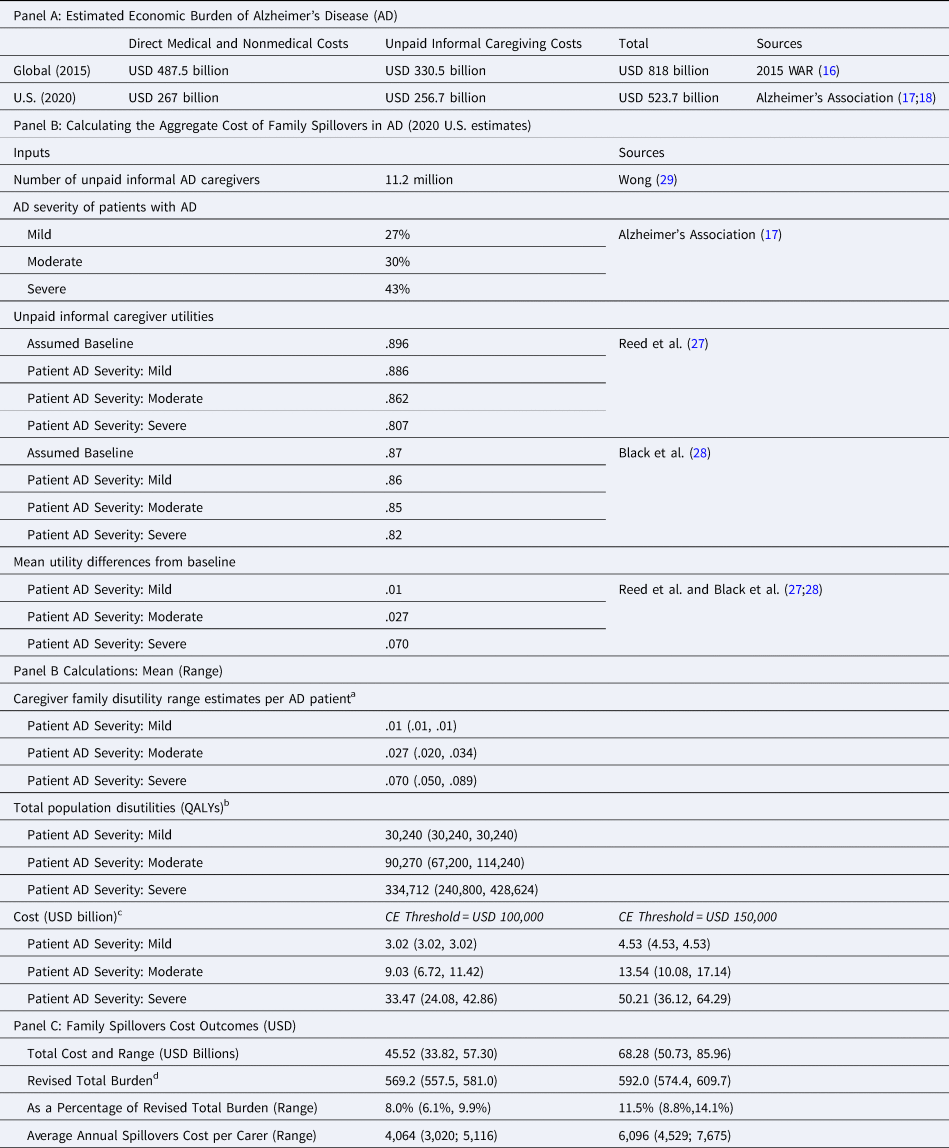

As reflected in Table 1, global estimates from the 2015 WAR and 2020 U.S. estimates by the Alzheimer's Association reveal that costs of unpaid informal care account for 40 to 49 percent of the total economic burden of AD.

Table 1. Estimating the Aggregate Cost of Family Spillover in AD

a Caregiver family disutility range estimate = mean (utility − baseline utility).

b Total population disutilities = caregiver disutility × % of AD patients within severity × total number of unpaid informal caregivers.

c Cost = CE Threshold × Total population disutilities.

d Revised Total Burden = USD $523.7 Billions (from Alzheimer's Association) + Family Spillovers (Mean and Range).

With an aging population, the AD caseload is expected to increase dramatically to 13.5 million patients in the USA and 115.4 million worldwide by 2050 (17–19). In parallel, the total global economic burden of dementia is expected to exceed USD 2 trillion by 2030 (Reference Rice13).

Although already high, prior estimates of the economic burden of dementia fail to capture a number of hidden costs and may significantly underestimate the true economic burden of dementia. For example, the impact on caregiver quality of life and their own increased healthcare resource use secondary to depression, anxiety, and physical ailments were not included in the 2015 WAR and Alzheimer's Association estimates.

The Impact of AD on Caregivers: Burden and Family Spillovers

AD is a neurodegenerative disease that leaves patients increasingly dependent on caregivers for assistance with their activities of daily living and health maintenance. As such, the Green Park Collaborative recognized early on that increasing caregiver burden was linked to patient outcomes and recommended that caregiver burden and AD patient outcomes be assessed in the same trial to better assess their relationships (20).

Considering that approximately 85 percent of all informal (unpaid) caregivers are family members (21), the impact of AD on family members is an important consideration for a holistic value assessment of AD medicines. Family spillovers in AD are especially important considering caregivers of people with AD have higher levels of burden compared with caregivers of patients with other health conditions (Reference Gonzalez-Salvador, Arango, Lyketos and Barba22–Reference Brodaty and Donkin24).

Although caregiver burden has traditionally been measured as indirect time costs to caregivers, caregivers clearly experience additional challenges in regard to their physical and emotional well-being. The Alzheimer's Association reports that twice as many caregivers of those with dementia compared with caregivers of people without dementia indicate substantial emotional and physical difficulties (18). In fact, 66.7 percent of caregivers evaluated in the What Matters Most (WMM) study reported that their physical health had suffered (Reference DiBenedetti, Slota, Wronski, Vradenburg, Comer and Callahan25). Caregivers of people with dementia also have a higher prevalence of anxiety and depression (anxiety: 44%, depression: 30–40%) compared with caregivers of individuals with stroke (anxiety: 31%, depression: 19%) (18). Such health impacts were also associated with more frequent doctor visits, outpatient tests and procedures, and use of over-the-counter and prescription medications (18).

Caregiving often affects not only the caregiver's health but also their work and finances. Among employed caregivers (who are 60% of all dementia caregivers), 57 percent reported needing to go in to work later or leave earlier and 18 percent reduced their work hours due to care responsibilities (18). Furthermore, dementia caregivers bore almost twice the average out-of-pocket costs of nondementia caregivers (USD 11,535 vs. USD 6,209) in 2020. Overall, caregivers of patients with AD experience “high rates of burden and psychological morbidity as well as social isolation, physical ill-health, and financial hardship” (Reference Brodaty and Donkin24) that result in more caregiver workdays missed, decreased caregiver productivity, and increased caregiver healthcare resource utilization (26).

The GERAS study, a prospective observational study of 1,497 informal caregivers of patients with AD, and the Adelphi Real World Dementia Disease Specific Programme assess the progression of caregiver burden and its impact on caregiver quality of life (Reference Reed, Barrett, Lebrec, Dodel, Jones and Vellas27;Reference Black, Ritchie, Khandker, Wood, Jones and Hu28). Although the EQ-5D—as a utility measure with a stronger focus on physical health—may be less sensitive in capturing the impact of caregiving on caregiver mental health, the results of the GERAS study and Adelphi Real World Dementia Disease-Specific Programme were used to estimate the aggregate cost of family spillovers.

A straightforward calculation of the aggregate and per carer cost of family spillovers is summarized in Table 1: the estimated aggregate cost of family spillover secondary to caregiver utility losses would be on the order of USD 57 billion (range: USD 45–68 billion). Omitting the aggregate cost of family spillovers secondary to caregiver utility losses would, thus, lead to over a 10 percent (range: 8–13%) underestimation of the economic burden of AD. With the increasing AD caseload, we expect more caregivers to be affected and the aggregate cost of family spillovers to also increase substantially. The estimated annual cost of family spillovers per carer would range from USD 3019 to USD 7675.

Because unpaid caregiving can affect both caregiver productivity and health, caution must be taken to avoid double-counting the disutility of unpaid caregivers and the monetary value of their caregiving time (Reference Grosse, Pike, Soelaeman and Tilford30). Our calculation minimizes double-counting by utilizing EQ-5D inputs, a health-related quality of life measure also commonly used to assess health utility of patients.

Implications for AD Care and Policy Making

The physical, emotional, social, and financial consequences of AD affect not only patients with AD but also their family members who provide care. As such, economic evaluations from the societal perspective encompassing benefits and disutility for all individuals affected are better suited for more holistic value assessments of AD medications and other interventions. Decision makers would then have the option to incorporate fit-for-purpose information to inform their assessment and ultimate appraisal decisions regarding coverage and reimbursement.

The EQ-5D utility survey instrument may not be ideal to measure the impact of caregiving on dementia caregivers given its primary focus on physical health. Other utility measures such as the Short-Form 6D (SF-6D) should be evaluated for better measurement of the mental health of dementia caregivers and potential improved accuracy in capturing caregiver health utilities.

Rewarding pharmaceutical companies for developing AD medications that not only preserve cognitive function but also significantly reduce family spillovers will require adjustments to the conception and application of cost-effectiveness (CE) thresholds. Methods to incentivize innovations yielding higher value to society must also be developed alongside broadening value frameworks.

Incorporating broader value frameworks in technology assessments would not be feasible without the upstream availability of evidence from clinical trials. Although clinical trials have traditionally been designed to achieve regulatory approval based on clinical efficacy for patients, studies should proactively be designed by, for example, “core outcomes sets” to assess other elements of value important to patients, carers, and society (31).

Policy Forum and HTAi Board members identified several reasons for the recent proliferation of novel value frameworks: rising healthcare costs, more complex health technologies, perceived disconnects between price and value, changes in societal values, as well as additional considerations such as ethical issues and the greater empowerment of clinicians and patients in defining and utilizing value frameworks (Reference Oortwijn, Sampietro-Colom and Habens8). For optimal use of limited healthcare resources, it is imperative for the HTA community to also develop “systematic, explicit, timely, and transparent” decision-making processes (Reference Oortwijn, Sampietro-Colom and Habens8) to ensure patient access to high-value medications. Failure to incorporate family spillover effects in CEAs will likely lead to an underestimation of the true burden of AD and true incremental value of new and existing AD medications. More comprehensive value assessments would ideally support better societal resource allocation and incentivize innovation that improves patient and societal outcomes.

Key Questions

• Would broadening value frameworks increase the budget impact or would willingness-to-pay thresholds simply increase?

• Would including other elements of value disproportionately benefit some therapeutic areas, while disadvantaging others?

• How would broadening value frameworks affect the overall HTA process? Will the process take longer? Will there be ad hoc approaches?

• What would be the repercussions in the reimbursement process?