Cross-clamp ischemia during carotid endarterectomy (CEA) might be entirely preventable, either by using a carotid bypass shunt during arterial repair in all patients or by selective use of a shunt in patients who require one based on some highly reliable test or measurement of collateral blood flow and ipsilateral cerebral perfusion during cross-clamp. This test could be direct patient examination if the procedure is performed under regional anesthesia, or stump pressure measurement, transcranial cerebral oximetry (TCO), electroencephalography, somatosensory potentials, or transcranial Doppler under general anesthesia.Reference O’Kelly, Butcher and Marchak 1 - Reference Radak, Sotirovic and Obradovic 7 To date, no monitoring technique or shunt practice during CEA has been proven superior to another; indeed, shunting has not yet been proven to improve outcome from CEA.Reference Chongruksut, Vaniyapong and Rerkasem 8 Cerebral monitoring and shunt use for CEA is, currently, subject to technology available in the operating room as well as anesthetist and surgeon preference.

Our approach to avoid cross-clamp ischemia has been selective shunting based on monitoring during general anesthesia. When TCO became readily available in our operating room, we set out to prospectively compare it with traditional stump pressure measurement. We wished to compare these two relatively simple measurements with predetermined criteria for shunting, the clinical endpoint being symptomatic cross-clamp ischemia. Our hope was that strong concordance between the two would allow us to forego invasive stump pressure measurement.

Methods

All patients in the study received a general anesthetic. A balanced technique using volatile agents, muscle relaxant, and short-acting narcotics was most commonly used. Use of specific drugs and agents was not restricted by protocol and left to the discretion of the attending neuroanesthesiologist. Blood pressure (BP) was invasively monitored via radial arterial catheter. Heparin (100 U/kg body weight) was administered 3 minutes before carotid clamping. BP during carotid cross-clamping was maintained within the range of preclamp BP to 20% greater than preclamp BP. Vasoactive agents were used as required. Following carotid artery declamping, protamine was administered for heparin reversal.

Our microsurgical endarterectomy technique has already been described.Reference O’Kelly, Butcher and Marchak 1 This was a prospective study, data were collected for each individual patient at the time of surgery and with predetermined criteria for shunt insertion as described in the following section.

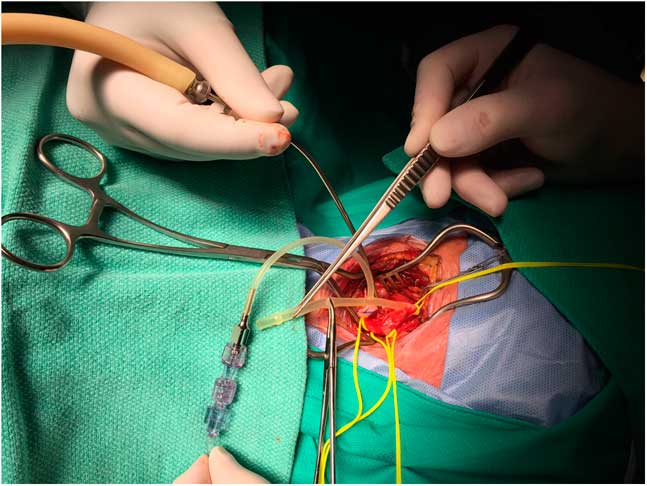

TCO using near-infrared spectroscopy technology was monitored continuously throughout all procedures with probes placed on either side of midline of the high forehead (Philips, Somanetics, INOVS-OXIMETER, IntelliVue G5-M1019A).“Stump pressures” were measured after cross-clamp and arteriotomy using a Bard Brener carotid bypass shunt, which has a “T” design. The proximal limb of the shunt was clamped with a mosquito clamp, the distal limb inserted into the internal carotid artery (ICA) beyond the stenosis, and the T arm of the shunt connected to saline filled tubing, which was attached to a pressure transducer (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Method of stump pressure measurement using a Bard Brenner carotid bypass shunt (see text for details).

If cerebral saturations fell 10% or more and/or the mean ICA stump pressure was found to be less than 40 mmHg, the proximal limb of the shunt was inserted into the common carotid artery proximal to the stenosis, the mosquito clamp occluding the shunt removed, and the patient was “shunted.”

The TCO response to shunting and the cross-clamp time was recorded. The presence or absence of angiographic “collateral” supply to the ipsilateral hemisphere was recorded when it was clearly seen on computed tomographic angiography (CTA). This was defined as a visible either anterior or posterior communicating artery, and, in the case of the former, a visible first segment of the anterior cerebral artery as well.

The patient’s neurological condition upon awakening was recorded, and a cross-clamp ischemic deficit determined by the presence of a hemispheric neurological deficit detected immediately upon awakening.

Results

Three hundred consecutive patients operated on by a single surgeonReference Findlay, Marchak and Pelz 9 between 2009 and 2016 were included in this study. During this period, five patients were excluded because TCO was not available or failed during surgery, and another five patients were excluded because the shunt catheter could not be safely passed into the distal ICA (for stump pressure measurement) because of complex anatomy, namely a vascular loop, a very high exposure or resistance felt on attempted catheter placement. Our hospital Ethics Committee reviewed this study and concluded it was a quality assurance project not requiring either patient consent or Committee oversight.

The mean patient age was 69 years and 73% were men (Table 1). The indication for surgery was transient ischemic attack in 141 (47%), nondisabling stroke in 75 (25%), and asymptomatic stenosis in 84 (28%). The degree of stenosis as reported by the neuroradiologist on CTA was 50% to 69% in 27 (9%), 70% to 80% in 156 (52%), 81% to 90% in 78 (26%), and 91% to 99% in 39 (13%).

Table 1 Patient characteristics

* Student t test.

† Fisher exact test.

The mean baseline cerebral oxygen saturation was 73%, and there was either no change or an increase in saturations after cross-clamp in 89 patients (30%). A drop of less than 5% occurred in 90 patients (30%), 6% to 9% in 72 (24%), a drop of 10% to 14% in 28 (9%), a drop of 15% to 19% in 12 (4%), and a drop of 20% or greater in nine (3%). A total of 49 patients had what we classified a potentially dangerous desaturation of 10% or greater (16%) (Table 2).

Table 2 Transcerebral oximetry (rS02)

The mean stump pressure (in mmHg) was 50 or greater in 156 patients (52%), 40 to 49 in 80 (27%), 30 to 39 in 36 (12%), 20 to 29 in 23 (8%), and less than 20 in five patients (2%). A total of 64 patients (21%) had what we classified a potentially dangerous stump pressure of less than 40 mmHg (Table 3).

Table 3 Mean ICA stump pressures (mmHg)

Seventy-five patients, 25% of the study population, were shunted (Table 4). The indication was a combined low saturation and stump pressure in 38 (50% of the shunted group). Desaturation alone (i.e. stump pressure 40 or greater) prompted shunt insertion in 11 patients (15% of the shunted group), and a low stump pressure alone (i.e. no concomitant significant change in saturations) led to shunt insertion in 26 patients (35% of the shunted group). As shown in Table 1, there were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between those patients who were shunted versus those who were not, with the exception of collateral blood supply. In the 160 patients in whom the presence or absence of collateral supply could be clearly seen on CTA, 97% not shunted had collateral flow versus 77% of those shunted (p<0.005).

Table 4 Shunted patients: n=75 (25%)

Of the 49 patients who were shunted on the basis of cerebral oxygen desaturation, all but seven recovered to saturation within 10% of their baseline following shunting.

The mean cross-clamp time in the whole study population was 25 minutes, 25 minutes in the patients not shunted, and 23 minutes in those that were shunted.

During the study period, there were two patients who awoke with hemispheric neurological deficits, and both demonstrated watershed infarcts on postoperative imaging. The first was a patient excluded from the study whose TCO showed a 20% desaturation after cross-clamp, but a shunt could not be inserted for either stump pressure measurement or shunting due to the high and distal stenosis and repair. This patient awoke slowly with a profound left-sided weakness and neglect. CTA showed the arterial repair patent but subsequent computed tomography scanning revealed a right frontoparietal watershed infarct. The patient was ambulatory but had permanent and disabling hemiparesis at 1-year follow up. The second was a patient included in the study whose fall in saturation was 15%, but then recovered to a 10% desaturation from baseline during cross-clamp, and whose stump pressure was 40 mmHg. His postoperative motor and speech deficit recovered to baseline (he had suffered a minor stroke) within 24 hours, but he had a new 1.5-cm subcortical parieto-occipital infarct on a computed tomography scan done before discharge home. No other patients in this series that awoke with unexpected global or focal hemispheric deficits.

Discussion

Cerebral ischemia as the result of carotid cross-clamping during CEA is a less common cause of stroke because most persons have sufficient collateral flow to sustain their cerebral hemisphere for as long as it takes to complete the procedure and restore flow.Reference Kretz, Abello and Kazandijian 10 When cross-clamp ischemia does occur, it is immediately apparent. Patients undergoing surgery under regional anesthesia become less responsive or agitated and develop contralateral weakness, which reverses with declamping. When significant cross-clamp ischemia occurs during general anesthesia, patients awaken slowly and demonstrate global contralateral weakness or paralysis, hemineglect, and often ipsilateral gaze paresis. Watershed distribution infarcts become apparent on follow-up brain imaging.

A more common cause of stroke complicating CEA is thromboembolism or delayed postoperative carotid occlusion at the repair site, often related to a technical flaw in the repair.Reference Ferguson, Eliasziw and Barr 11 , Reference Rothwell, Eliasziw and Gutnikov 12 This type of postoperative stroke differs from cross-clamp ischemia by having an onset hours after the procedure.Reference Rothwell, Eliasziw and Gutnikov 12 - Reference Sheehan, Baker and Littooy 14 Much of the literature on monitoring and shunt use examines a delayed and often 30-day stroke riskReference Chongruksut, Vaniyapong and Rerkasem 8 as an endpoint when the pertinent strokes related to cross-clamp are immediately apparent.

Arguments against routine shunt use include that it is clearly not required in a large number of patients, shunt placement is sometimes difficult (such as in patients with distal “high” carotid bifurcations or long atherosclerotic plaques) and shunt insertion itself might precipitate a stroke by causing plaque embolization, injuring the distal carotid or creating an arterial dissection. The presence of a temporary indwelling shunt makes the technical performance of CEA more demanding. For those reasons, some surgeons have a policy of never shunting, but a popular middle approach is selective shunt use based on some assessment of brain condition or hemispheric blood flow during cross-clamp.Reference O’Kelly, Butcher and Marchak 1 , Reference AbuRahma, Mousa and Stone 4 , Reference Bond, Rerkasem and Counsell 15 , Reference Rerkasem and Rothwell 16

We set out to compare stump pressures with what for us when this series began was a relatively new technology for carotid surgery, TCO. Simple and entirely noninvasive, we hoped TCO could replace the trouble, time, and potential danger of stump pressure measurement.

Stump pressure is the perfusion pressure transmitted around the circle of Willis and down the internal carotid beyond the cross-clamp. Aside from subjective impression of the degree of “back bleeding” down the ICA after cross-clamp, stump pressures were the first actual measurement used during CEA to help guide shunt placement.Reference Crawford, DeBakey and Blaisdell 17 - Reference Moore and Hall 19 A number of thresholds for stump pressure, ranging between 25 and 70 mmHg, have been proposed, below which shunting would be indicated.Reference Howell 2 , Reference Chongruksut, Vaniyapong and Rerkasem 8 , Reference Calligaro and Dougherty 20 Using direct neurological examination as the “gold standard” for cerebral ischemia in patients undergoing CEA under regional anesthesia, it was found that a stump pressures less than 40 mmHg had a sensitivity of 57% and specificity of 97% for predicting a neurological deficit.Reference Hans and Jareunpoon 21

Transcranial cerebral oximetry with near infrared spectroscopy provides a value for regional cerebral oxygenation (rS02) beneath the scalp monitor, which is a composite of both arterial and venous oxygenation.Reference Waltzman, Kurth and Montenegro 22 , Reference Owen-Reece, Smith and Elwell 23 The signal may be contaminated by blood flow in extracranial tissues and TCO monitors placed for CEA detect frontal lobe blood flow, not necessarily reflecting middle cerebral arterial perfusion. As with stump pressure measurements, a TCO’s specificity has been shown to exceed its sensitivity.Reference Samra, Dy and Welch 24 Despite these limitations and that the cutoff point indicating definite cerebral ischemia is unclear, the simplicity of TCO makes it appealing as a cerebral perfusion monitor for CEA.Reference Pennekamp, Bots and Knappelle 25

A weakness of this study is that it could not generate sensitivity, specificity, or predictive values for TCO or stump pressure measurements because those calculations require values tested against a gold standard of cerebral ischemia. In the case of CEA, the best gold standard is the clinical status of patients being monitored under regional anesthesia, and for a number of reasons our operations were and are performed under general anesthesia. Our hope was to demonstrate that we could eliminate invasive stump pressure measurements, but we found there was not a good concordance between TCO and stump pressures, and a significant number of shunted patients had a shunt placed based on a low stump pressure alone (35%), or desaturation alone (15%). At the same time, a welcome finding in our study was that using this “dual monitoring” with TCO and stump pressure measurement virtually eliminated cross-clamp ischemia as a complication in a large series of CEA patients.

We did have one serious case of cross-clamp ischemia during the study period, but his local anatomy precluded shunt placement indicated by a 20% drop in ipsilateral rS02 (stump pressure could not be measured). A second patient and one included in the study suffered a small watershed infarct with borderline values in both TCO and stump pressure (down 10% and 40 mmHg, respectively), and our decision not to use a shunt when both monitors were “borderline” was a mistake that we have learned from.

As already mentioned, there is variability in TCO and stump pressure thresholds for shunt insertion reported in the literature, and the values we chose and (and considered conservative) remain unproved. A reasonable question was whether choice of a stump pressure below 50 mmHg as threshold would have captured the patients shunted based on TCO alone. Of the 80 patients whose stump pressure was between 40 and 49 mmHg, six were among the 11 patients were shunted because of a desaturation of greater than 10%. A stump threshold of 50 mmHg would therefore have resulted in 80 additional shunt insertions and still missed five patients with what we classified a “dangerous” cerebral desaturation. Conversely, if we had chosen a desaturation of 5% or greater as threshold for shunt insertion, we would have shunted an additional 72 patients, only 12 of whom were among the 26 patients shunted based on stump pressures alone. So adjusting to more conservative thresholds for either of the two monitoring techniques studied would have led to far greater shunt use but not the same patient population that we shunted in this study.

As stated at the outset, the ideal monitoring technique and optimal threshold for shunt is not yet known, but in our opinion the dual method described in this report appears additive, almost eliminating cross-clamp ischemia, providing a shunt can be inserted under the anatomical conditions imposed by the patient.

It is probable we shunted more patients than required. Shunt requirements when surgery is performed under regional anesthesia ranges from 10% to 20% of patients.Reference Stoneham, Stamou and Mason 26 Others, however, have raised the possibility that subtle neurocognitive decline following CEA (quite apart from the global hemispheric deficit evident upon awakening used as the endpoint in this analysis) might be related to cross-clamp hypoperfusion, an argument for routine shunt use.Reference Mocco, Wilson and Ducruet 27 , Reference Ghogawala, Westerveld and Amin-Hanjani 28

We did find that the presence of an anatomically intact circle of Willis predicts sufficient collateral flow and a reduced probability that a shunt will be required, consistent with the findings of others.Reference Wain, Veith and Berkowitz 29 , Reference AbuRahma, Stone and Mousa 30 In our experience, however, it is sometimes impossible to be certain of circle of Willis anatomy on CTA, which is known to be fully intact in only about 50% of the population.Reference Alpers, Berry and Paddison 31 Our results suggest that the combination of TCO and stump pressure measurement is a highly effective way of selecting patients for shunt insertion during CEA.

Disclosures

The authors do not have anything to disclose.