1 Introduction

The end of the third millennium bc was a time of considerable changes in Egypt and the Near East. The previous centuries had seen the consolidation of large polities based on a complex bureaucratic structure both in the Nile Valley and Mesopotamia. In the case of Egypt, the administrative organization of the kingdom expanded and diversified after the construction of the great pyramids at Giza (roughly after 2500 bc): more governmental departments, more officials and scribes, tighter control of the provinces and their resources, and a plethora of rank and function titles. As for the Near East, large supra-regional polities unified Mesopotamia and, occasionally, adjacent areas as well. The old city-state system was replaced by new political forms, more encompassing and, apparently, more intensive in their exercise of power over an incomparable more extended territory. Perhaps not by chance, these transformations coincided with the expansion of trading and exchange networks over vast areas in the second half of the third millennium bc, with Egyptians involved in the Levant and north-eastern Africa (Nubia, Punt and beyond). At the same time, Mesopotamian activities extended toward Anatolia, the Middle East, Arabia, and India. Both spheres were connected through major trading cities like Byblos and Ebla.

Then, these early “imperial” formations experienced a transformation into lesser-scale polities, a process that overlapped only partially in both regions. When the Egyptian monarchy disintegrated around 2160 bc, more or less at the same time as the Akkadian Empire, this was hardly the traumatic process imagined by earlier scholars. Some regions of Egypt thrived, particularly in the north, now organized as the regional Heracleopolitan kingdom, encompassing part of the Delta, the Fayum and most of Middle Egypt. In the case of Mesopotamia, the process was more gradual. The relatively short-lived Ur III monarchy still managed to control part of the former Akkadian Empire, but it disintegrated by 2004 bc and was replaced by several competing kingdoms. Meanwhile, Egypt was reunified again around 2050 bc or slightly afterward. However, the newly restored monarchy faced considerable opposition in some regions, had to cope with regional lords who held their own political and economic agendas and failed to create a tax system capable of capturing resources at the same scale as in the third millennium bc. After two centuries of unification, the country entered again into a long period of political fragmentation shortly after 1800 bc.

Whereas both regions remained distinctive and direct contact between them – diplomatic or economic – was marginal, they experienced similar vicissitudes despite differences in their political organization and socio-economic relations. This opens a fascinating window for comparative research that may help place both regions and their respective societies in a broader perspective and help us to understand early political dynamics: How did these state societies react to the increase and extension of exchange networks? Did specific urban sectors influence decision-making, even limit royal agency? Was centralization more apparent than real, such that other social forces had the potential of shaping power and limiting royal agency? What was the role of mobile and “marginal” people in these transformations? Which mechanisms favored the accumulation and circulation of wealth, and to what extent did kings succeed in capturing, even monopolizing, critical resources and depriving potential rivals of doing the same? Did the palatial sphere impose its cultural values and normative codes easily outside the narrow circle of the court, or, on the contrary, were they challenged by alternative practices deeply rooted in society?

Thus, by comparing ancient Mesopotamia (Seth Richardson) and Egypt (Juan Carlos Moreno García) during a specific period – the late third and early second millennia bc – we analyze the possibilities, challenges, and limits in the construction of power experienced by two Near Eastern societies (see also the inspiring work by Baines and Yoffee Reference Baines, Yoffee, Feinman and Marcus1998). Behind a façade of robust kingship and centralized authority, it may be possible to grasp other realities in which power, wealth and status were negotiated and distributed between different actors and through various channels. From this perspective, what appears, superficially, to be highly idiosyncratic societies may reveal unexpectedly shared features and structural differences that can open helpful venues for comparative analysis of statehood in the ancient Near East. In the following sections, “comparison” means exactly that: an assessment of disparities as well as similarities. We do not find that the cultures under study were either essentially the same or too different to compare. What these societies may have had most in common were challenges of similar kinds: finding balances of state, civic, and private power, overcoming barriers of distance, and using both material wealth and ideological persuasion to produce a coherent and organized sense of governance.

2 The Organization of Power in Babylonia: Problems and Prospects

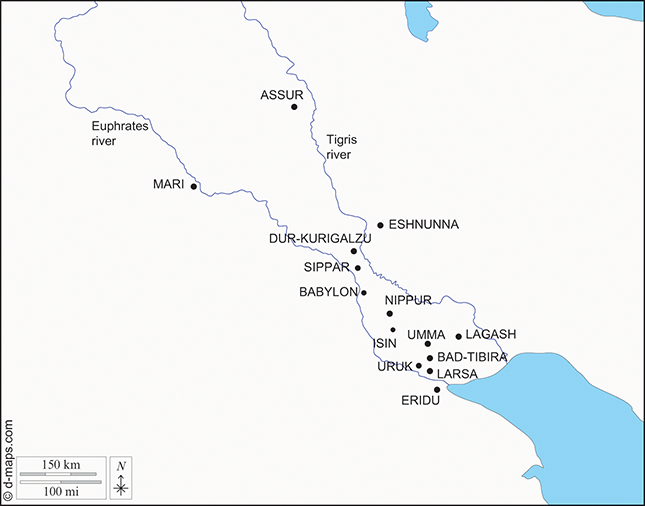

The “organization of power” is no new topic for comparative scholarship on ancient Mesopotamia (Figure 1).Footnote 1 The conflicts and cooperations between different nodes and levels of political authority that lay at the center of early state-building projects have long attracted the attention of historians working in both history and archaeology. Mesopotamia, as one of the earliest known state societies, obviously plays an important role in such studies. Attempts to define how power “worked” in early Mesopotamian society have emerged from two general directions: First, from studies of archaeology and economic-administrative texts – essentially social-science approaches, focusing on material goods in the formation of cities, institutions, and agricultural production – and second, from literary approaches, humanities approaches forefronting themes such as kingship, temple religion, and social orders.Footnote 2 From these two lines of attack, we have derived two rather divergent pictures of Mesopotamian political culture: one which was almost obsessively committed to administration as a language of control; and another which was preoccupied with lofty theological and ideological notions of kingship and cosmos.

Figure 1 Map of Mesopotamia

Whether this culture ran from earth to heaven, or heaven to earth, it was an emphatically urban and political one. But it was one of profoundly heterodox makeup; a world in which power did not have any single defining look, feel, or obvious linguistic, religious, or ethnic self-conception. Across thousands of years of political culture in the Babylonian south – to say nothing here of the Assyrian north, which was a substantially separate cultural formation – Mesopotamian state authority was shaped by such a variety of conditions as to defy general characterization. This political variegation is reflected in the iconographic, linguistic, and even literary-generic diversity of Mesopotamian culture, forms which rarely seemed to jell or sit still long enough to achieve the iconic “look” of power seemingly characteristic (if deceptively so) of Egypt.

This lays down multiple challenges for anyone wanting to make synthetic and general statements. To address “Mesopotamia” as a socio-political whole, we would have to lump together in a single cultural framework the experiences of city-states, territorial states, larger conquest and “national” states, and empires spanning multiple ethnolinguistic regions, all across three thousand years. Thus to speak of a singular or distinctive way in which Mesopotamian power was organized across the longue durée will always be somewhat reductive.

My approach will be twofold. First, the reader should be prepared that I will make relatively brief general statements about early state organization as points of departure for more detailed descriptions of the many deviations from those norms. It is important to forefront diversity and heteropraxy as the norms of Mesopotamian power, because the exceptions are simply too numerous to be exceptions. Second, I will use the Old Babylonian period (hereafter, “OB”) as a template for Mesopotamian state society, though noting differences with other periods along the way. There are good reasons to choose the OB. For one thing, it is the period I know the best; for another, it is roughly contemporary to the time discussed here by Moreno García for Egypt. More substantially, it is the period by which states had had more than a millennium to coalesce their portfolio of claimed powers into forms coherent and well-documented enough to work as an object of analysis. These claims still fell demonstrably short of reality, but they illustrate the early state’s fundamentally “presumptive” nature. This is not just to say that states didn’t have all the powers they claimed – this observation by itself would be banal – but that the desire for those claims to be(come) true was the discursive motor generative of their eventual realization.

I begin with a general and somewhat idealized description of the ways in which power was organized in the OB period – about how it worked (“Paradigms and Models”). I will then turn to some theoretical problems with those archetypes, not only because they impose some limits on our knowledge (as they do), but also because they present opportunities to reinterpret what those limits on knowledge themselves can tell us (“Problems into Possibilities”). In the following sections, I will consider organized power in different sectors: the central role that cities played in state formation; the attempts of states to territorialize or provincialize the land over which they held sway; the durable presence of nonurban and non-state bases of political power; and the networks of merchants, wealthy households, and temple estates which interacted with but remained autonomous of state power. I am on the watch for structural elements which both furthered and limited the powers of central states. My discussion of the “organization of power” necessarily engages a review of more sectors of society than just royal/state power, but I do limit my interest to the political role of other actors, not to their economic or social power. The word “organization” is therefore as important as “power”: Where I discuss merchants, scribes, priests, and judges, it is to assess the roles they played in constructing and exercising political power embodied within the state system.

2.1 Paradigms and Models

I am dubious about descriptions of how states work; my view is that they often don’t, at least not fully or according to plan. But the ways they don’t work have the potential to be as informative about political cultures as the ways that they do.

Whatever the approach, I begin with a sense of the main lines along which power was organized in the OB period. Following the demise of the centralized Ur III state, Babylonia was divided between small territorial kingdoms centered on five major cities: Isin, Larsa, Uruk, Babylon, and Ešnunna. (Mari, to the northwest on the Euphrates, was another important peer state, but at a substantial geopolitical distance.) The fortunes of these cities waxed and waned within the period, but none was regionally dominant for more than a generation or two. Alongside these states, dozens of petty kingships sprang up in smaller cities; in some cases, we do not even know where those cities were, or when exactly their kings ruled. The OB is commonly described as one of incessant warfare, but this characterization should be tempered somewhat: Violent interstate competition in lower Mesopotamia was concentrated in the 180 years from 1915–1735 bc, less than half of the 400-year period. Still, the quest to militarily reassert a single hegemon over the lower alluvium following the fall of Ur was the single most important effort to “organize” power, and warfare and conquest remained important to the state project.

Within their local orbit, these Babylonian kingdoms relied on methods of governance used in many other periods. Dynastic palace organizations used subjugation by force to effect rule, but also power-sharing with the cities, temples, and local elites they recruited as clients. Many cities and temples had preexisting traditions and identities, and came equipped with their own lands, clients, and representative bodies (priests, judges, assemblies, etc.). These substructures of power could be co-opted or colonized by ruling dynasties, but they could not be wholly erased or subsumed. Studies of OB Sippar (Harris Reference Harris1975), Nippur (Stone Reference Stone1987), and Ur (Van De Mieroop Reference Van De Mieroop1992) provide important accounts of these dynamic urban environments and the interlocking communities inhabiting them. As Andrea Seri showed in her 2005 survey of local power, the everyday contact people had with officialdom was with mayors, canal-inspectors, city gatekeepers, and elders, not the viziers, generals, and governors whom those men served (Figure 2). It is thus important to begin with the sense that kings and palaces headed up umbrella organizations under which other subsidiary bureaus maintained their own discrete local authority. It would be too much to call this a “federal” structure of kingship, but it is important to recognize from the first that distributed sovereignty was the rule.

Figure 2 Early Dynastic limestone statue of Ur-Ešlila, a city elder (ab-ba uru) of Adab, dedicated to the god Ninšubur in honor of a local king of Adab named Bara-ḫenidu, ca. 25th/24th bc. Statues like these marked the allegiance of city officials who managed everyday affairs to rulers who were more remote from the populace.

Outside and beyond the “organelles” of local institutions, Babylonian states built wealth, subjects, and power in much the same way other Mesopotamian states had, both before and afterward: through their control of land (Renger Reference Renger1995). State land (presumably appropriated) was doled out to clients in exchange for service and in-kind taxes. This practice bound many people at every level of society to the palaces, from individual sharecroppers, to soldiers and workers ready for war and work, to grandees and governors ruling whole districts. Even cities and temples with their own lands were sometimes required to tithe up to the Crown based on the political fiction that their lands were held at the pleasure of the king. Land was thus the foundation of state wealth, far and away its most important asset and source of revenue. Yet palace lands never included all the land of any kingdom. We are aware of many private landholders, as well as transhumant and tribally organized groups living outside of or loosely affiliated with state control, and there clearly were significant sedentary rural populations not living under the rule of states at all. To these points, I will return in in what follows.

Particularly interesting is the use by OB states of officers and private factors to convert in-kind taxes – from the agricultural sector (i.e., crops and animals), through loans and sales – into storable institutional wealth in the form of silver. Credit sales and productive loans appear in contracts between private actors, but often the profits went to the palaces as a system of state finance. We do have evidence for similar mechanisms from other periods, but the OB case looks uniquely “privatized.” Certainly, the fiscal problem itself was not unique: Mesopotamian states of all periods – indeed every pre-modern state with an agricultural economy – faced the same challenge: There was only so much barley, cheese, meat, and beer any palace could ever store; conversion into non-spoilable wealth was the goal.

Babylonian palaces also built revenue and economic power through secondary production, operating breweries, workshops producing textiles and crafts, harvesting wool and sheepskins, baking bricks, and leasing out draft animals; they operated productive “bureaus” wherever resources and opportunities arose. Many such areas of production were leased out to concessionaires, some of them endowed with titles reflecting rights to produce and collect. States also collected taxes on trade goods, often through “Overseers of the Merchants” stationed in city “harbor” districts (kārums). Imposts were collected on products brought from afar (sometimes paid in gold, the possession of which may have been a state prerogative) just as readily as on local products sold in bulk. The effectiveness of states to capitalize on commercial activities, however, was limited.

The OB has been characterized as an epoch of decentralized power, where state business was largely outsourced to local units, entrepreneurs, agents, and traders. These states were administratively laissez-faire, through what has been called the Palastgeschäft (“palace business”) model (Yoffee Reference Yoffee1977). Against this image of detached state control, socioeconomic life outside the state sector seems to have been more robust in this time than it ever had been (and would not be again until the Neo-Babylonian period). Long-distance private trade is documented between Ur and the Persian Gulf (thus connecting Mesopotamia, secondarily, to the Indus River Valley and even central Asia); between Sippar and northern Syria; between Babylonia and the Assyrian trade system running up into Anatolia. The reach, volume, and sheer value of the trade goods (silver, tin, copper, textiles, wine, etc.) are arresting, especially considering that the trading agents in these systems operated privately, mostly outside of state purview.

Closer to home, everyday archival texts paint a picture of a relatively well-to-do private citizenry. Householders in many cities bought and sold land (Figure 3), extended credit, owned slaves and cattle, and passed their estates on to their children through inheritance and into other families through marriage. These practices are reflected in the textual genres that arose to support their increasing autonomy, especially contracts and letters. We see law and epistolary expression reaching much higher degrees of sophistication than in previous ages, and something like an emerging burgher-class sensibility. This was also the age in which we find some of the best evidence for political life and power at the local level. City assemblies, town judges, and local notables acting as witnesses show us a citizenry participating in community decision-making. Literary production, too, was in a golden age of sorts, with some of the best-known works in Sumerian copied extensively even as new epics, stories, and scientific literature were being composed in Akkadian. Altogether, we see a powerful palace sector, a vigorous commercial world, an emerging civil society, and a landscape full of non-state tribes and villages. Altogether, this cast of characters must call into question any presumption that states were exclusively in control of “organizing power.”

Figure 3 Plan and measurements of three adjacent private houses belonging to men named Kilari, Ḫululḫulul, and Šara-zida. From the Ur III city of Umma (ca. 2050 bc). Alongside the “great households” of palaces and temples, private households became increasingly important nodes of power from the Middle Bronze Age onward. VAT 07026 (Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin).

2.2 Problems into Possibilities

One difficulty in analyzing any Mesopotamian state has to do with our own terminology: How easily we assume, from the words in Sumerian and Akkadian for “king” (lugal/šarru) and “kingship” (nam-lugal/šarrūtu), that an extrapolated term for “kingdoms”Footnote 3 – that is, states – must also have existed. But (importantly) neither language extended the semantic sense to a substantive categorical noun “kingdom,” or developed a workable term on any other semantic basis to mean “state,” “nation,” “country,” and so on.Footnote 4 I am not making a claim that because the word “kingdom” was absent from the lexicon that the idea did not exist; territorialized states were an important aspiration of Mesopotamian polities even if as yet unrealized. But a Mesopotamian state was something substantially organized around a person and an office, not a territory. Babylonian kingship was a political formation in which no political or legal-juristic identity was ever made between royal power, territory, and the things and people “contained” within it. This was largely true for most states even up through the early modern period. To the extent that we (sometimes necessarily) speak about ancient states in these ways is largely a framework imported from assumptions about what countries are and do by the standards of post-1789 ad nation-states. So any talk about “parts” and “wholes” working together for Babylonian antiquities must begin by shedding the erroneous premise that “states” existed as territorialized “wholes”: bounded territories within which there were regularized relations of law, political membership, and common markets.

The theoretical work to be done, then, is to try to understand what kingship states which were not “kingdoms” might be. Mesopotamian states were palatial estates, great households with assets in the form of clients and properties scattered irregularly throughout the land. These households were preeminent in scale but not in kind, asymmetrically rather than categorically more powerful than the other institutions to which we might compare them (i.e., temples and cities), merely stronger in some functions than in others. The challenge is to examine the interplay of parts without presupposing the totalities we expect of modern nation-states.

Despite the fact that states varied over time, many institutional issues reappeared across periods. The division and distribution of resources and authorities perennially created alliances and tensions between different groups of actors. Mesopotamian politics included relations between palaces, temples, and private households; the king and his court; officials and scribes (noting some overlap); ruling and subject cities; markets and institutions; locals and colonists; herders and farmers; and administrators and dependents. The successful establishment, distribution, and exercise of power required to manage all these groups, resources, and people involved the manipulation of political traditions which all had their own long histories. Thus, although there was almost limitless innovation, the discourse of traditionalism invited the emulation of many recurrent forms and arrangements. This produced much of the same “invented tradition” language about the restoration of authority and order as we find in Egypt.

Royal language tells us much about not only ideals but also shortcomings and practical politics. As my co-author points out, there are ineluctable distinctions to be made between the official historical accounts written by central states – in rhetoric simulating a world of total and frictionless authority – and the realities of governance, which demanded a politics of negotiation: political buy-in, compliance, and persuasion. The “command rhetoric” used by Mesopotamian kings in their narratives, as in Egypt, was designed to suggest that they exercised complete control over virtually all aspects of state capacity (in warfare, religion, production, knowledge, etc.). But this is deceptive of both fact and even voice. The voice of certainty deliberately obscured not only matters of fact but also the mechanics that made kingdoms function. There is therefore a comparison to be made not just between fiction and fact when reading royal literature, but also between the totalizing ideologies of states and the realities of delegation, power-sharing, and elite settlements. Royal literature routinely magnified the authority of individual rulers to the purpose of symbolically investing a discourse of state functionality in the sole figure of the king as an ideal person. But these symbolic absolutes, reified at the state center, were in reality at variance with the tools and roles of everyday governance which were (necessarily) distributed spatially and socio-politically. It must interest us not only that these major disparities existed but also why this was so consistently the case.

Some of the most durable aspects of the organization of power are in evidence, then, not where the king commanded and his state obeyed, but where the Crown as an institution had to negotiate with temples, civic bodies,Footnote 5 and merchants in order to effect its authority. We tend to think of such groups as if royal power was held over them de jure, but it is better to think in terms of the integration, co-option, or de facto recognition by states of the pre-existing authorities of other power-holders. The management of “elites”Footnote 6 involved the delicate art of balancing entrenched local networks with meritocracies (both “closed-rank” and “open-rank” systems); controlling competition within and between bureaus and centers; harnessing and crosschecking the flow of information and intelligence from different administrative units through separate chains of command; both permitting and restraining independent action; and, of course, maintaining accountability. To these purposes, there were many tools in the Crown’s toolkit: offices and concessions to confer and take away; tax obligations to impose or remit; whole fields of activity to regulate, from animal-skinning to gold-smithing to legal practice; and, of course, the state’s recourse of “legitimate” violence.

Meantime, elite groups had their own internal dynamics of power to navigate: maintaining systems of patronage,Footnote 7 nepotism, and inherited position; expanding power through intermarriage and business alliances; buttressing social authority through displays of wealth and prestige. There was the matter of working out pecking orders between elites whose power was based in different institutions. Would a royal tax-collector outrank a city judge in a dispute? Was a priest superior to a mayor? Who would decide? Such things were not spelled out in black and white. There were subtle shades of social surveillance to define and maintain elite status and individual reputation; to police in-group coherence without succumbing to excessive gossip, jealousy, or denunciation. And colonized elites had to balance the authenticity that underwrote their local authority (as judges, priests, mayors, etc.) with duties to the (non-local) political center which could require them to act publicly against the local interests they supposedly represented.

This then raises the question of how autonomous of states were any of the significant political actors or sectors. It is clear that there were always some resources, people, and spheres of activity – and therefore some politics – which lay outside of state control; the question is only how much of this activity is visible to us. The OB was not the first period in which non-state activity is attested, but it is perhaps the first with plentiful evidence in the form of letters, sales, and loans, although in some cases apparently, private merchants worked in tandem with palaces to resell state resources.Footnote 8 Thus we see not a sharp divide between Babylonian state and non-state sectors, but two arenas of overlapping action. By contrast, to the north in the contemporaneous Old Assyrian period, a centuries-long overland trade between the city of Aššur and trade colonies in Anatolia shows us a more emphatic dichotomy of state/private activity.

What really makes the OB stand out is not only the explosion of legal contracts forming the core apparatus of private business, but also the distinct cultures of householders, businessmen, and officials that emerge in the voice of their letters, where nonstate competition was worked out. There can be little dispute as to the self-awareness and existence of this group: As in Egypt, it entailed the management of households whose members ranged from pater familias down to the sheep; a robust epistolary community; and a terminology of status interaction, including the “influential” (kabtu), “gentleman” (awīlum), “servant” (ṣuḫaru), the “great” and the “small” (rabû and ṣiḫru), all knit together by a language of friendship, fraternity, and favor. In their letters, we can see class identities being developed and worked out, often with much squabbling.

Social power was perennially under revision, horizontally as much as vertically. Networks of social and economic power existed outside of the state sphere, and this generated its own kind of politics. But this hardly means that elite identity was secure, stable, or teleologically emergent toward success (quite the contrary: a class of “businessmen” does not re-emerge until the first millennium). I am struck by the difference here with the Egyptian case: The collective elite identity so confidently on display in the Tale of Sinuhe cannot be summoned forth from the Mesopotamian literary landscape. Elite identity was very real for individuals, but it remained highly atomistic in political terms, and not part of a “common culture.”

Two spatial features both empowered and constrained palatial estates as political institutions trying to emerge into states: concentrated urban nodes and a territorially diffused wealth of arable land. The combination of cities – dynamic social and economic engines – and a nearly limitless amount of agriculturally productive countryside – making “pockets of power” possible almost everywhere in the alluvium – provided kings with unparalleled resources with which to build state power. However, the same conditions permitted a ubiquity of competitors to and emulators of state form and function to flourish, from institutions to individuals. These power constraints acted politically, symbolically, and infrastructurally. It is with this sense of interaction at and between different scales that I go forward to think about power’s spatial and social organization, and with some sympathy for states: As in any culture, there was enough competition and comparison at all levels of state society as to make the Crown’s task of “organizing” it a plate-spinning act from beginning to end.

2.3 The Cities

From the earliest point when we can identify political entities in Mesopotamia and in every period going forward, they were based in cities. The historical states that ruled the lower alluvium were without exception urban kingships. It is almost impossible to overstate the role of cities in the configuration of social, political, and economic power. Indeed, when Uruk’s urban magnitude sprawled across the meadows and marshlands of southern Iraq in the mid-fourth millennium bc, we have no clear evidence of kings or palaces; as far as we can see, there were cities before there were states. But there were temples, and these had priests, officers, staff, dependents, grain reserves, and land, not to mention ideological power and control over the writing technology by which these assets are known to us. It is likely that these temples had some political authority over at least part of the urban community. Urban form and culture would remain the most durable elements of the political landscape, more durable even than dynasties themselves. The city of Uruk, for instance, would outlive not only the five local dynasties that sporadically ruled from it between ca. 2600–1800 bc, but another dozen other states that laid claim to it through the millennia. As a rule, cities both preexisted and outlived kingships.

But if cities were durable, they were also highly protean. If Mesopotamian urbanism was “bigger” than its Egyptian counterpart, it was also more volatile. Cities could attain vast sizes and then shrink back to much smaller footprints. The same city names endured, but the political primacy of one city could be easily replaced by another. For instance, the city of Lagaš in the third millennium was an unrivaled power; by the first millennium, it was barely remembered. Akkad’s unification of lower Mesopotamia in the 24th century bc was a feat that kings tried to emulate for centuries, but soon after the dynasty’s demise, Akkad was abandoned and referenced only by historical tales and antiquarian restoration projects. Babylon’s first dynasty began around 1890 bc, ruled lower Mesopotamia by 1750 bc, and then became the preeminent city of the region for the next 1,500 years; yet we are not even sure it existed before 2000 bc. Thus, though we recognize that cities were engines of social, economic, and political power, and some showed incredible resilience, their political preeminence could be ephemeral.

The symbolic preeminence and relative predominance of cities can also distract us from their variability over time. Mesopotamian cities were much smaller across the second and into the early first millennium than they had been in the third millennium. It is also worth remembering that the majority of Babylonians in all periods did not live in cities; our impression that this was an urban culture is largely shaped by the fact that virtually all of our sources come from cities. If Babylonian cities seem therefore not so “elusive” as their Egyptian counterparts, they also run the risk of overdetermining how we tell the story of Mesopotamian social power.Footnote 9

Still, cities were the centers from which much rural production was administered, on which markets were focused, and where political, religious, and cultural forms and tastes took shape. This leads us to focus on the activities of the administrators, scribes, and businessmen whose names populate the cuneiform contracts, letters, and literature, all drafted, archived, and found in cities. For example, one thinks of successful OB long-distance traders like Ea-nāṣir of Ur, bringing copper ingots across the Persian Gulf; merchants like Šēp-Sîn, who in his letters arranged orders for tin, juniper, and aromatics, running business from Larsa to faraway Susa and collecting kilo upon kilo of silver;Footnote 10 or the slavers and wine importers working northern Syria and the Diyala from the Sippar kārum (“market district”). There were the high administrators working locally, assigning farmland and converting in-kind taxes into durable silver for the states: Balmunamḫe in Larsa, Šamaš-ḫazir in Jaḫrurum-šaplum, and Utul-Ištar in Sippar and Babylon. And there were the learned (as opposed to, say, administrative or military) scribes, such as Sin-nada of 19th-century Ur, training students in his house on everything from elementary texts to Sumerian laments; Nabi-Enlil of 18th-century Nippur, boasting of the superiority of scribal training in his city; or Ipiq-Aya of Sippar of 17th-century Sippar, copying lexical lists, Atra-ḫasis, and Naram-Sin and the Enemy Hordes.Footnote 11 In these same historical milieux, we find other men bearing a dizzying array of state titles such as estate “farmer” (ensi2), tax-collector (šu.i), overseer of merchants (ugula dam.gar3), and herd supervisor (sipa); civic titles like head of assembly (gal.ukkin.na), mayor (ḫazannu), and headman (rabiānu); temple titles such as high priest (sanga), administrator (ša3.tam), and cleric (gudu4); and military ranks such as general (ugula mar.tu), captain (nu.banda3), and colonel (pa.pa) – among many others. Some of these offices were sinecures or prebends, with designated incomes or rights-to-collect attached to them; some were assigned by merit or inherited.

But many wealthy householders carried out their business without any titles at all – simply called so-and-so, son of so-and-so – private actors without institutional identity or authority. Often, roles depended on the needs of the moment: OB society was one in which flexibility between private and institutional roles were central to how things worked. Also significant: There is much evidence for the collective rights, properties, and obligations of professional and official groups – merchants, soldiers, judges, plantation managers, votaresses, farmers, diviners; occupational classes like bakers, carpenters, millers, and basketmakers; and communities of ethnic, foreign, or metic residents (Isinites, Kassites, Elamites). Most of these individuals and groups, with identities autonomous of states, were documented in cities. Anything like “class consciousness” was at best incipient and inchoate, but what group identities there were, semi-independent of state authority, were all realized in urban venues of decision-making: in city assemblies, collegia of judges, district councils, city wards, temple courts, the “cloisters” in which votary women lived, and harbor districts. All these bodies exercised some internal legal and administrative powers over their members and properties.

These powers were never neatly or clearly “nested” à la Weber within rational structures of state law and administration. So we are left with a terribly messy picture of “how power worked,” because the combination or bases of authority behind decisions seem as numerous and protean as the actors. The same kinds of functions could be performed by different officials in different ways, with little obvious reason for doing things differently. To take but a single (but significant) example, the measurement of fields, important for ownership and taxation, is known to have been performed by (among others): surveyors (abi ašli), clerks (šà.tam), accountants (sag.du5), “gentlemen” (awīlū), city elders (šib ālim), the “old men” (awīlū lābirutê), military scribes (dub.sar zag.ga), supervisors (šāpirū), administrators (rābiṣū), judges (di.ku5), military governors (šakkanakkū), and captains (pa.pa).Footnote 12 It is never made clear why certain officers rather than others were called on to perform this specific action. In many cases, not only did more than one type of official preside over acts of measuring, but it was done under the “supervision” of a (non-human) divine emblem.

If one takes field-measuring and extends it as a metaphor for other types of governmental or collective action – judging, taxing, mobilizing manpower, maintenance of infrastructure, and so on – it seems simply impossible to draw a coherent flow-chart of power. I do not mean to imply that sense and order cannot be found: often enough, judging was done by judges, messages were brought by messengers, and city matters were deliberated by assemblies. I mean to say that governance was not only handled heterogeneously, but also that Mesopotamians themselves rarely expressed the idea that any particular officer was exclusively appropriate to perform any particular task.

One way we might make sense of this seemingly chaotic picture is to try to understand the system’s complexity as its virtue; to see what is seemingly asystematic as … flexible. What Mesopotamian state society displays is a laboratory in which a diversity of resources and infrastructural powers allowed equally diverse pathways for the allocation of labor, resources, and talent. A wide array of actors and institutions permitted and diffused the inevitable pressures of ambition and competition. Institutions limited risk and overuse, and regulated community goods; private households allowed for the realization of opportunities; and both interacted in the same markets and other public arenas. This environment of complexity never emerged or resolved toward any perfect equilibrium – many letters tell us how often ambitions were thwarted, resources were wasted, officials quarreled, and power was misused – but it arguably created systemic resilience. And indeed those same letters are suffused with expectations that these things should work: if only person X hadn’t been greedy, or person Y so lazy, everything would have worked out fine. These potentialities, hopes, and ambitions that urban elites had for stability were real, even if problems and failures are better attested in the record. It is the existence of expectations that gives more reasonable testimony for the “organization of power” than their satisfaction. Mesopotamian cities were, in their most abstract sense, the formal expression of a desire for order, places where one could hope to find “truth and justice” (kitti u mīšari), while the dangerous and disordered world outside the city walls – in the steppes, meadows, and mountains – was kept at bay. It is not only that cities were where one might to find power; cities were the only places where organization was possible.

2.4 Provinces and the Territorialized State

Because cities were such dominant communities, the provincialization of Mesopotamia emerged only slowly. Areal units never really took on the conceptual importance that nodal cities had, as the denomination of territory makes clear. From the earliest writings of the Uruk period, we can reconstruct a toponymic repertoire composed entirely of city names and devoid of regional ones (as far as we can read them; see Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Englund and Krebernik1998: 92–94). It was not until the Early Dynastic period – not earlier than ca. 2500 bc – that any city controlled enough land to require specific names for ex-urban territory or terms for boundaries.Footnote 13 Only one royal inscription from this time describes anything like a systematic provincialization of territory. Giša-kidu of Umma (ca. 2400 bc) described the frontier of his state as it was supposedly given on an already-existing “monument of the god Šara”:

The breaks in the text do not permit a full reconstruction of the boundaries Giša-kidu describes, but the perimeter may have been something like 67 kilometers, giving us an area for the Umma state of about 357 km².Footnote 15 What is remarkable is not so much the information given by such an inscription, but that no other king would offer any similar “cadastral” description of his state for another 300 years.Footnote 16 Simply put, where kings were interested in conveying geographic information, it was overwhelmingly about loci that had been conquered, not areas under control.

The process of formal territorialization was not much advanced in the Akkadian dynasty. Under Sargon of Akkad and his successors, a few parts of the state were named for the individual people, elite households, and cities that controlled them, rather than as toponyms in their own right. However, despite this dearth of areal nomenclature, Akkadian state practices do show a sense of territorial awareness: large tracts of land were routinely reassigned from one city to another, new administrative units were created far from city centers, and the titles of some urban grandees were recoded to mean something less like “city lord” and more like “provincial governor.” Notwithstanding, when an enormous revolt was organized against the Akkadian state, the leaders of the uprising were all called kings of cities and not heads of provinces; the centers of power remained firmly urban.

In later Mesopotamian states, there was more emphasis on the organization of territory into provinces, but the process never really came to completion. In Ur III times, the land was organized under “governors” (ensi2) and “generals” (šagina) appointed to cities, and peripheral conquered areas were termed “the lands” (ma-da). That the cities could be understood as the “capitals” of whole provinces is suggested by the structure of the formerly independent state of Lagaš, which was now divided into three districts (Girsu, Lagaš, and the gu2-ab-ba, lit. “bank of the sea”). For a period of about half a century, deliveries of in-kind goods and livestock to the state (in Sumerian called bala, lit., a “turn[ing]”) were organized by province, but the role of provinces is somewhat obscured by the fact that the governors delivered but sometimes also received bala-payments. It is thus not clear whether the provincial system enabled what was fundamentally a “tax” paid to a center, a structure of entitlements for elite persons, or a redistributive arrangement benefiting the cultic economy of the city temples rather than for provinces as such.Footnote 17

In the OB period, the evidence for territorial administration is even less regular. This is unsurprising given the division of the alluvium between multiple warring city-states with differing governance and accounting systems. But we do get some glimpses of territorial administration. The documents of the Larsa state, for instance, show that enormous tracts of agricultural lands were organized under its authority. Hammurabi’s Babylonian state divided its southern territory into “lower” (šaplûmFootnote 18) and “upper” (an.ta) regions and recognized other regional districts (halṣum).Footnote 19 Some “governors” (šāpirū and gir3.nita2) presided over cities (Sippar, Kiš, Dilbat, Rapiqum, etc.), but others over terminologically indistinct (but nevertheless specific) regions called “the lands” and “the river district.” The greatest amount of textual specificity about production and taxation, however, was still produced at the city level, where local watering districts (ugārū) were responsible for payment of taxes and corvée labor, even down to the individual level as specified in field-rental contracts. Rural lands were represented as administrative categories from an urban perspective, not neutral geographic facts. Thus, city identities remained at the fore while regional-provincial ones were always relatively weak.

Provincialization increased in the Kassite and Middle Babylonian periods, when as many as fifteen provinces (piḫatū) were administered by a central government at Babylon through governors called šandabakkū.Footnote 20 This may reflect the long period of low urbanization from the Middle Bronze through Iron II period – more a sign of weak cities than of strong provincial identities. The administration of the city-province of Nippur is well known, but its texts constitute about 90 percent of all documentation for the period, most from only about half the time span of the dynasty (ca. 1360–1225 bc), so it is unclear how representative the corpus is. Some lands remained under the direct administration of the king and semi-independent grandees called “manor lords” (bēl bīti, lit. “master of households”), but it is unclear if these estates were really “provinces.” Notwithstanding, a larger number of territories were now named for tribes or regions rather than cities, and this seems to reflect state structure as more regionally defined.

Despite the low profile of provincialization, the lands were important to states: The majority of people and productive wealth in Babylonia in all periods were in rural territory rather than in cities. Nor did cities administer all the territory in their hinterlands – beyond their immediate arable fields and second-/third-tier villages lay vast swaths of unorganized land.Footnote 21 In virtually all periods, our texts mention places that could not have been much further than the farming villages under urban administration but were clearly not directly exploited. We know these places existed, but we cannot say much about them. In effect, the enormous substrate land wealth that lay outside the scope of states remains hidden from us. This again reflects on state ontology. The absence of provincial identities and the preponderance of urban power reflects just how referential the state project really was: states documented what they administered, not everything that existed. Babylonian state ideology was content to sound as if it governed all the places or nodes that “counted” – that is, that kings held kingship over a collection of individual cities rather than over a single, unified “land.” But we should avoid thinking that what was left unexplained was unimportant.

Structurally, Babylonia as a “state” thus perennially appears to have been a galaxy of cities with orbital towns; beyond and between, there was unadministered interstitial territory which was never clearly demarcated or denominated. How “provincialized” Mesopotamian states were may depend on whether one interprets the administrative divisions named for cities as implicating (some? most? all?) of their associated ex-urban territories. But at no point was a single system to organize all state land into administrative units either achieved or sought. In contrast to a retrospective reconstruction of territoriality in the Egyptian case, the hard evidence for administration by territory in Mesopotamia remains wanting, despite our modern analytic preferences to define states (ancient and otherwise) as structured on familiar principles of regularly divided land.

The corollary is that the constraint which limited kingship as an urban institution also kept in check the ambitions of local elites who might have tried to establish provincial power bases, as they sometimes could do in Egypt. As much as Babylonian states were unsuccessful at creating isomorphic spatial entities called “provinces,” setting a lower boundary on their power, that same boundary fixed a ceiling on the aspirations of governors and city lords. It remained difficult for local peers, powerful though they might be in local towns, to cobble together clear, heritable, and reproducible political identities in the same way states could. Until the Neo-Babylonian period, elites were not a class with political ambitions (in either the Marxist or Weberian sense), a coherent cultural habitus (Bourdieu), or “autonomous” of imperial power (Eisenstadt). And to the extent that they did achieve such definition and consciousness, they remained rooted in cities, not in provinces. The elite networks of power that undergirded the historical states superimposed on Babylonia’s landscape were not based on regional or provincial identities.

2.5 Cities and Their Others

Although kingship was a fundamentally urban form of power, cities themselves were semi-autonomous of royal power. Moreno García’s observation that Egyptian cities grew in the early second millennium as older crown centers were abandoned (see p. 50) excites an important question on the Mesopotamian side: given the centrality of royal authority and cities to Mesopotamian political power, why were they so uneasily integrated into one another? Kings styled themselves as kings of specific cities (Ur, Akkad, Ur again, Babylon) and their main palaces were built there, but the cities were not “theirs”; they did not, as a rule, found or own those cities, acts which were prerogatives of the gods. Babylonian kings founded all kinds of new settlements, often eponymously named, as “fortresses” and “harbors” – purpose-built military and trade centers – but these were generally not capital cities. For instance, Paul-Alain Beaulieu (Reference Beaulieu2017: 7) writes of a new Kassite royal city, “there is no evidence that the Kassite rulers intended to replace Babylon with Dūr-Kurigalzu as capital of their kingdom. Indeed, they continued to claim the title of ‘king of Babylon’.” Conversely, although many Babylonian cities developed kingship traditions,Footnote 22 others never claimed to be the centers of royal states at all, or only briefly flirted with ephemeral local kingships: Fara, Abu Ṣalabikh, Zabalam, Nippur, Sippar, and so on, even when they were economically or ideologically important.Footnote 23

This underscores a fundamental distinction between kingship and cities as distinct loci of political power. Babylonian kingship was an inextricably urban form and yet unable to independently reproduce itself as that form, whereas cities could carry on, autonomously and quite successfully, without needing to assert or brand their identity with dynastic kingship. Even the etiological Sumerian King List, profoundly inaccurate in factual terms, correctly acknowledges this difference through its narrative structure: cities pre-existed (and survived) kingship – beginning as it does: “When kingship descended from heaven, the kingship was in Eridu … ” – but kingships were transient and very mortal. This principle is exemplified in Sumerian city laments, which make clear that kingship was dependent on the well-being of tutelary gods and the patronized cities.

I will return to discuss non-royal city institutions: wards, assemblies, merchants, temples, cloisters, guilds, and so on. But first I will make a distinction of royal from urban power on territorial grounds, to give a sense of the nonurban settlements founded and funded by the Crown. If the Crown built few cities, it did build other kinds of places – fortresses, storage-and-distribution centers, palace-(town)s, manors, military colonies, brick-firing plants, caravanserais, and threshing centers. The social lives of these places are nowhere nearly as well-studied (or, admittedly, represented by evidence) as proper cities, but they provide nevertheless a glimpse of nonurban state power.

In the Early Dynastic period, royal building work was almost exclusively within cities; nonurban royal settlements are sparsely attested.Footnote 24 But the Akkadian kings made extensive use of redistricting and purchases to carve off some productive hinterlands from city control, appointing new governors and deploying gangs of workers in the countryside. Few nonurban places were ever mentioned in the royal inscriptions of the Akkadian kings, but we can see that a great deal of administrative energy was focused there.

The ensuing Ur III period saw the Crown’s construction of distribution centers like Puzriš-Dagan and agricultural estates like Garšana (see Owen ed. Reference Owen2010). The Old Babylonian period provides sources for fortresses as diverse as Ḫaradum, a small desert fort on the middle-Euphrates with a modest civic life, and Dūr-Abi-ešuḫ, a multi-site complex that cycled equipment, provisions, and troops to and from other fortresses. The names of many fortresses are evocative of loyalism (“Fort {Royal Name}” was a common form), military ethos (“Claw of the God”; “Circle Fort”; “Watchpost”), and rural location (“Sandbank”; “Ox- Drover-Town”). Larsa in the Old Babylonian period and the narû-monuments of the Kassite period attest to the vibrant life of “manors,” the towns of powerful individuals who ruled them as personal domains. Many such places were simply called Āl-PN, “Town of so-and-so.” Thus, although Babylonian kings ruled as city lords through patronage and protection, they exercised more direct power outside of cities, where they acted as the masters of estates. This model is heuristically useful, allowing us to understand that every king was simultaneously a king of different places in different ways. It also hints at how royal power was perpetually constrained by the institutional power of socioeconomic elites in cities on the one hand and the diffusion of territorial power in a larger number of smaller places of the countryside. Babylonian royal power was a balancing act between these two realms of governance (or: “governmentalities”). We are looking not so much at a “two-sector” state as we are at two different kinds of kingship operating simultaneously.

We know much less of the many rural places and populations outside of royal emplacements: in trading posts, farming towns, and herding camps. These were little places that looked to towns rather than cities as their central places; where no state officer was stationed, no Crown property documented, and no taxes paid. No account of the “organization of power” could be complete without modeling these “unorganized” communities or the chieftains and elders who ran them (Selz Reference Selz, Charvát and Vlcková2010). We know these places were out there based on often single mentions in state texts: border towns, lonely farmsteads, and fishing camps; sheepfolds in the meadowlands, mudhifs in the marshes, watchtowers in the steppe; and Kassite outfits, Elamite camps, a “region of the tents.” One OB letter mentions a dispute adjudicated by city judges in a village called Laliya, which had a mayor and village elders (AbB IX 268); another mentions an expensive field located in Bitutu (AbB II 114); and a third orders a worker from Tell-Ištazri to report for duty at the palace gate (AbB II 17). None of these three places is mentioned in any other cuneiform text, but well-known enough for the letter-writers not to have to specify their location. But where were these places? How were they related to nearby states? Were they under their control, barely known, or torn between states? We cannot know. The problem is not small: most OB toponyms are attested only a few times. The relationship between poorly attested toponyms and state centers remains an intriguing macro-level historical question; our continued focus on better-attested places obscures how extensive undocumented toponyms really are.

Urban states and their associated settlements might thus be represented as flickers of light in a vast, dark space, where only a portion of the landscape was illuminated by the symbols and actors who made state power apparent. Another kind of power pertained in other places – the Places Where the State Was Not – a great “unorganized” part of the landscape that minimized its interactions with the rapacious men who styled themselves “kings” in sometimes nearby towns; an ancient lifeway not defined by kingship or cities.

If life outside of state society was actually the more typical experience for any given Babylonian person, this casts a different light on state claims. Take for example the repeated declarations of OB kings to have “gathered in the scattered people” and “settled them in peaceful abodes.” Given that few kings claimed control over territory (rather, over peer cities) – it seems likely that these in-gatherings were not forced population movements, but attempts to persuade, recruit, and maintain political clientele. Some significant portion of the rural population belonged to different states at different times; others remained unaligned with any state. There seems always to have been a broad and entropic landscape ready to absorb populations back into (as it must have appeared from the perspective of state ontology) a non-state “nothingness.” This unexpectedly inspires some sympathy for states: Their claims to control people were not confident, factual descriptions, but desperate attempts to sound as if this control might become real.

Non-state populations, whether they posed security risks or unrealized sources of income for states, were of varying importance across Mesopotamian history. Although cities were dominant in all periods, their size and number, relative to other kinds of settlements, varied dramatically from century to century. In the Early Dynastic period, 88 percent of the occupational area surveyed was located in settlements 100 hectares or larger: a thoroughly urbanized population. By the Kassite period, sites of this size made up only about 31 percent of all settled areas: a thoroughly ruralized population. Cities only returned as a majority form by the Neo-Babylonian period (Adams Reference Adams1981). There was also regional variation within periods. For instance, the region around Nippur perennially had more than twice as many small villages (2 ha. or less) as Uruk (Richardson Reference Richardson and Leick2007: 16). There was thus wide variation in the urban:rural populations from time to time and place to place. Accordingly, different cities had sometimes widely disparate experiences trying to regulate their control of hinterlands.

States we might think of as basically similar illustrate this variability. The OB kingdoms of Larsa and Babylon, for instance, were contemporary rivals and near-equals in terms of political and military power. But Larsa harnessed vast productive areas in its hinterlands: from Bad-Tibira in the west to Lagaš in the east, hundreds of surveyed fields were annually plowed, planted, and harvested in dozens of agricultural towns and estates. The kingdom had at least 8,223 hectares (82.2 km²) of arable land under state production in any given year; one single account text from Larsa (YBC 7238) alone documents more than 1,200 hectares of farmland. Babylon, by contrast, had a radically lower footprint in its rural hinterlands: despite a similar density of text types, the largest single register from Sippar (the best documented of Babylon’s subject cities) accounts for only 222.9 hectares of land (MHET II 6 894), a sixth the size of the land in the YBC 7238 account. The kingdom of Larsa appeared to exercise more power over a wider area than Babylon did; its officials, resources, administrative apparatus, encumbered persons, tax yields, and so on, reflect this.

In all periods, cities were centers of administration, organizing and exploiting agricultural wealth. Mesopotamian state power was always a mediation between centers and distributed bases of wealth. But wide variations in practice by period and area inflected the nature of rule in individual states, with results as diverse as the royal work camps of the Akkadian period, the state-run redistribution system of the Ur III bala, and the decentered manorial system of the Kassite period. Small differences of degree in the algorithms of production resulted in political-economic forms that were substantially different in kind.

2.6 Semi- and Informal Networks of Power

There were other networks of power-holders partly or wholly based in cities whose affinities did not lie primarily with state. The interests of local officials, family lineages, private households, and temple communities sometimes intersected or overlapped with those of royal households, but sometimes diverged from them. Competing cadres of officers, private entrepreneurs with goods to protect from taxation, and priests with prebends to pass on within their families all had assets worth withholding from state control.

One might object that “officers” do not belong on this list – that their very institutional titles mean they did not belong to “informal” networks. But titles were often given in de-facto recognition of an individual’s already-existing private economic and social power. Officials often bore titles that had little to do with the actual functions they performed. This is a well-known problem in Assyriology: “fishermen” sometimes turn out to be soldiers, “farmers” were county supervisors, “barbers” and “inn-keepers” were tax-collectors, “temple sweepers” and “shepherds” were only the supervisors of men who did the actual work, and the “Great One of the Assembly” was responsible for mobilizing field labor. The royal official called a rakbû appears most often as a messenger, but is also attested witnessing sales, collecting barley, and receiving taxes. Officials called “Overseers of the Merchants” dealt with credit and financing, but also acted as judges and transacted their own personal business. The responsibilities of officials to one another appear to be haphazardly individual and occasional, by title, type of action, and city. We cannot therefore always be certain whether in any given instance an official was acting in his capacity as an official, as a private person merely noted by/with his title, or whether titles inherently conferred broad powers to act in ways beyond what the titles described.

An example: Sin-nādin-šumi was a 17th century “diviner” (barû) by title and a servant of the King of Babylon. But his dozens of texts documenting activities over approximately twenty-five years have little to do with either divination or royal service. He mostly extended short-term loans of silver and grain and provided cultic sheep to the Šamaš temple in Sippar. He built up a regular circle of contract witnesses and partners as his personal business associates. He lived as a local grandee in the fortress town of Kullizu (“Ox-Drover Town”), and not as a functionary in a large city. This “official” was much more a financier and sometime state/temple factor than a mantic ritualist.Footnote 25

Of course, sometimes titles are clearly related to area of responsibility. Šamaš-ḫāzir, for instance, was the “registrar” (sag-dun3) for the farmlands of the conquered Larsa province; accordingly, he made field assignments to tenant farmers. Utu-šumundab, the “Overseer of the Merchants” at Sippar, mostly arranged credit sales to convert crops into taxable silver. City elders deliberated in the assemblies, judges judged, and tax-collectors assessed the dues owed on fields. Sometimes people did exactly what their job titles describe.

But even when we have a clear picture of what officials were supposed to do, it can be hard to understand how their job worked within an administrative system. There are few titles for which we can establish clear chains of command, either within or between branches of civil, military, or institutional administration. It can therefore be hard to say who anyone reported to, on whose authority they acted, or to whom the silver they collected would get kicked up. Nor can we in most cases know how or why people were selected as officeholders in the first place. Their first appearance in a text as an official is typically the first time they are attested at all; officials thus seem to materialize out of thin air. Career promotion is likewise difficult to track. We can point to a few instances in which a specific individual held first one title and then another. From the Late OB, the best-known cases are those of Utu-šumundab and Utul-Ištar, who were titled judge and scribe (respectively) in the 1640s, and then identified as Overseer of Merchants and Foreman of the Workers in the 1630s. But we do not know the reason for the title changes. One is left to assume these were promotions, but even this is unclear. As isolated cases, they cannot be held up as models of any tenure-track system.

However, states were successful at grafting a stratum of officialdom onto the class of landholders and merchants who were truly at the core of OB society. Official positions were really not specific jobs with specific duties answerable to a specific bureaucracy; they de facto identified individuals as palace clients, scattered throughout the kingdom and acting as royal agents on an as-needed basis, with broad latitude to act. While state businesses relied on authority delegated to them, their agency was used to build relationships and manage resources for their own personal affairs. This required local political alliances and business contacts in various sectors of the economy: in production, transport, storage, finance, and so on. One might better think of Babylonian officials as concessionaires, men – and they were almost always men – holding grants to command and collect, with basic obligations to deliver annual quotas of wealth to the state center.

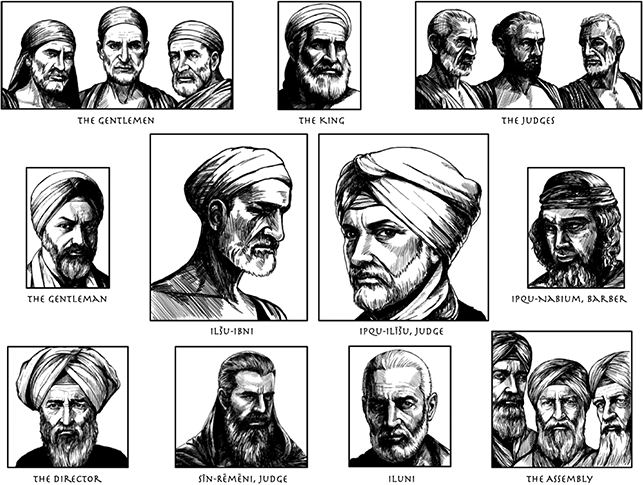

This environment led to local networks of officials who worked to meet Crown demands for taxes.Footnote 26 Some of these networks were formalized, such as judges in collegium (di.ku5.meš) or merchants incorporated as the kārum. Other groups were ad hoc, only visible to us when we can identify the repeated appearance of specific people in separate texts. These networks had clear advantages in that states did not need to invest much financial or political capital in running systems of government: granted titles were incentive enough. Officials, meanwhile, were free to operate as they liked through their “circle of acquaintances.”Footnote 27 The disadvantages, unsurprisingly, came when individuals used offices for personal gain and where official cliques formed, leading to competition and conflict. The delegation of authority was a slippery slope; as Moreno García felicitously puts it, it created a spectrum of administrative ethos ranging from “collaboration, negotiation, co-opting, favoritism, patronage [to] bribery.” The letters between OB officials include mutual accusations of hiding information, stealing money, working behind each other’s back, allying with rivals, snitching, or full-on denunciations to the king (e.g., AbB 12 93). A single lawsuit between individuals, like the one described here between one Ilšu-ibni and a judge named Ipqu-ilīšu, could entangle numerous officers and adjudicating bodies (in boldface; Figure 4):

Concerning what you wrote to me (Iluni), this is what you (Ilšu-ibni) said: “Ipqu-ilīšu the judge has spoken at length against me in the assembly. May a written order be issued that my complaint must be investigated.” … I have spoken to the gentleman and I have sent a strongly worded letter on the gentleman’s behalf for the director to Ipqu-Nabium the barber, a letter to Sîn-rēmēni the judge for his information, and a letter of the assembly to the honorable judges. Do not spare this Ipqu-ilīšu during the litigation in the assembly! In accordance with the words that you and he speak against each other in the assembly, the gentlemen will reprimand Ipqu-ilīšu the judge, and they will send me a copy of their tablets. The gentleman will inform the king according to the litigation that he will hear. (AbB XII 2).Footnote 28

Figure 4 The litigants and various officials adjudicating or intervening in the dispute between Ilšu-ibni and Ipqu-ilīšu the judge mentioned in the Old Babylonian letter AbB XII 2. Disputes between individual officials could entangle whole networks of public and private power.

Other letters about this same dispute vaguely mention a house, an ox, and a field. But we may never know what this quarrel was actually about, partly because the letters are preoccupied with specifying the relations between all the members of this network. The passage outlines a whole chain of prior communications, both extra-textual (“speaking against,” “complaint,” “investigation,” “litigation,” “reprimand”) and textual (a “written order,” “tablets,” three other letters, one of them “strongly worded”). None of these letters even hint at what the squabble was about. What we can divine from them is relatively abstract: the range/number of people, offices, and official bodies involved and a density of communications. We can see that nodes of semi-formal power could harden into factions or cliques, and that the affordances of the communicative system were themselves crucial to their creation. From the point of view of states, conflict needed to be channeled and controlled; from the local point of view, a circle of associates might align with a palace while also folding in private commercial, political, and even social goals and grievances.

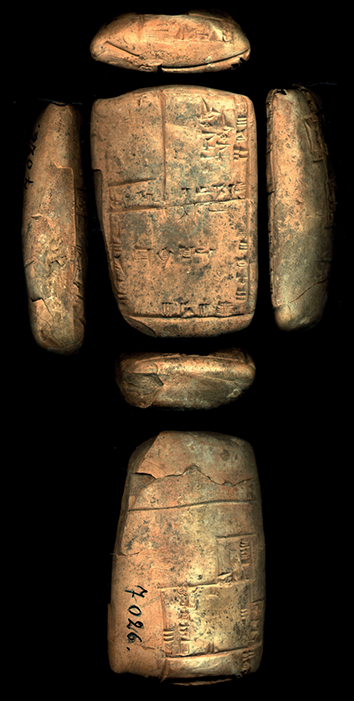

“Great households” were other sites of power formation. The term encompasses temples or any large establishments exceeding private households in size – with non-family dependents, properties, in-house accounting, and so on. Such organizations probably antedated states and writing altogether; it is not possible to overstate their importance across Mesopotamian history. Temples are our best examples: While serving as a locus for cult and sacrifice, they also provided close to the full portfolio of services that states offered with the possible exception of military defense. Temples were the social and sometimes residential homes for dependents; owned fields, animals, and slaves; ran mills, breweries, brick-making factories, bakeries, and workshops; conferred authority on civic and state proceedings; were staffed by priests, ritualists, gatekeepers, courtyard sweepers, snake-charmers, doctors, and scribes; collected taxes; financed caravans; appointed local notables as prebendiaries; accepted votary personnel into service; organized public labor; provided standards of weights and measures; held repositories of literary and scientific texts – the list could go on.Footnote 29 The larger temple communities of Ur III and Neo-Babylonian times commanded memberships and resources rivalling state capacity (Figure 5). While kings routinely laid claim to divine authority and temple patronage, temples were functionally isomorphic to states in many ways, sometimes even forming points of resistance to their authority.

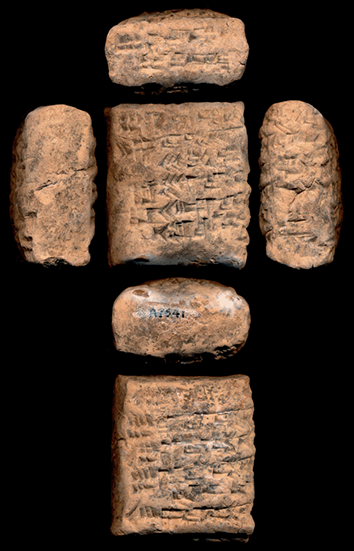

Figure 5 Old Babylonian cuneiform text from Nerebtum listing barley harvested from fields held by sanga-priests. Major temples sometimes held lands and resources rivalling those of the states in which they were situated.

Some collectives belonged to more than one orbit. For example, there were six orders of votary women in the OB whom we rather clumsily call “priestesses” (though we know little of their cultic obligations).Footnote 30 We can see that they functioned as entrepreneurs and heads-of-household, with special legal status and sometimes independent residences. These “religious” orders acted as franchises that allowed wealthy families to install daughters into tax-sheltered households from which paternal wealth could be expanded out of the reach of state taxation. Another example: Merchants’ collectives had clear obligations to deliver taxes and dues to the Crown, duties of civil administration, and even perform some ad hoc state diplomacy. But they did so by way of their primary local and long-distance trade and finance practices which enriched them as groups and individuals. Thus some classes of persons (metic citizens, soldiers, innkeepers, sailors, and judges) had special responsibilities to institutions, but also corresponding autonomies and privileges.

When it comes to informal networks of power, we may think of natal households as the most “natural” and bedrock form of social relations, with extended families controlling generational wealth. Descent is indeed indicated in Babylonian documents as the core of identity – one was named “So-and-so, son of So-and-so” – and some networks were centered on kinship ties. However it is very difficult to reconstruct most Babylonian family trees beyond a three-generation horizon, which seems to reflect the reality of families’ ephemeral nature. Indeed, the power of the most important people in OB documents cannot be tied to large families (just as they cannot consistently be tied to titles).

Principles of lineage and dynasticism were not even so clearly at the core of OB kingship as one might think. Although the First Dynasty of Babylon was comprised of a single line of descent over 300 years, the contemporary throne of Larsa was occupied by men from more than a half dozen lineages. Not once in any royal inscription, hymn, or year-name does any of the sixteen kings of the Isin I “dynasty” call himself the son of any previous ruler, even though we know that some were.Footnote 31 Descent and dynasticism were not forefronted ideologically, despite what we might suppose of the importance of lineage to the so-called “Amorite dynasties.” Other Mesopotamian states were different: Some Early Dynastic rulers propagated images of their families on plaquesFootnote 32; the Ur III royal family was exceptionally extensive; and the Assyrian King List took great pains to confabulate an unbroken line of descent across almost 2,000 years. The role of descent was thus emphasized to different degrees in different periods, but family networks were not always the “natural” sites of power formation that that we might expect them to be.

Important families, however, show up in almost every era. Several prominent families of merchants and landowners are known from Sargonic Nippur. Five generations of the Ur-Meme family held on to a clutch of titles as priests and governors in the same city under the kings of Ur (Figure 6).Footnote 33 In the former case, generational wealth proceeded from finance; in the latter, primarily from the incomes attached to prebendiary offices. At OB Sippar, we find prominent families such that of as Ilšu-ibni, Overseer of the Merchants, with four generations attested holding also judgeships; of Ipiq-Aya, with six generations attested, known as merchants, judges, and scribes mastering literary masterpieces;Footnote 34 of lamentation priests such as Inanna-mansum and Ur-Utu, with up to seven generations known, with significant interests in landholding, beer brewing, and the cultic economy of sacrifice. Some actors, such as some nadītu-women, accrued enough wealth to split away from their paternal households and begin their own lines of inheritance. The role of families seems to have grown in later periods. For instance, a majority of economic activity documented at 6th-century Uruk (once again a large city of ca. 12,500 persons) can be connected to about six dozen families,Footnote 35 and hundreds of texts from 5th-century Nippur detail the business of the wealthy Murašû family, with interests in landowning and finance.

Figure 6 Seal of Lugal-engardu, son of Enlil-amaḫ, prefect of the Inanna temple in Nippur and priest of Enlil (fl. ca. 2050 bc). Lugal-engardu was a third-generation member of the so-called “House of Ur-Meme,” a five-generation family which spanned the entire 21st century, perhaps outlasting even the Ur III dynasty itself. Members of this family held titles as scribes, provincial governors, and priests.

An important question for the study of ancient Mesopotamian families has been the extent to which kinship relations formed the basis for the accrual and generational transfer of wealth in state societies. Opinions diverged after a proposition by Soviet scholars that families lay behind most Mesopotamian economic and social formations. No clear answer ever emerged from this debate,Footnote 36 but it is undeniable that kinship structures played important roles in some times and places. For OB times, this has been studied in detail at Ur, at Nippur, and at Sippar, with especially clear results for the concentration of landholding, titles, and professions within single families.