You can jog with earphones and a hoodie on, and no car is going to drive up on you and perform a citizen’s arrest or shoot you. Nobody is going to bust in your house performing a raid and shoot you while you’re asleep. Roll up that yoga mat up [sic] and get to business.

—Alicia Garza to Stacy Patton, Washington Post, June 2, 2020

A good way to explain to kids #blacklivesmatter: “You like this black lady right? … You would be sad if a police officer hurt her right? Well this is the current country we live in where someone you like can be hurt by the color of their skin and people in charge aren’t doing a fucking … thing about it … Raise kids who give a fuck and you gotta give a fuck.

—Nicole Byer, Instagram, June 2, 2020As protests against police killings swept across the United States in 2020, white Americans appeared to support Black Lives Matter (BLM) at higher rates than in the past, measured both through opinion polls and movement attendance (Cohn and Quealey Reference Cohn and Quealey2020; Harmon and Tavernise Reference Harmon and Tavernise2020). Speaking to this trend, many BLM leaders, including movement co-founder Alicia Garza, called upon white Americans to engage in sustained political work (Patton Reference Patton2020). This included encouraging white people to think about how they engage their children in movement efforts. With viral social media posts explaining “the talk” Black parents have with their children about police, celebrity host Nicole Byer, for instance, urged white parents to explicitly discuss race in conversations with their children instead of remaining silent on the issue (Guerrasio Reference Guerrasio2020; MacIsaac Reference MacIsaac2020).

Both the explicit call upon white people to fight white supremacy and the linkage of race to parenting during this moment suggest the normative demands of the BLM movement may have spurred at least some white people to change their parenting regarding race. This could be of great political consequence considering the importance of parents as socializing agents (Jennings and Niemi Reference Jennings and Niemi1974; Niemi and Jennings Reference Niemi and Jennings1991; Oxley Reference Oxley, Bos and Schneider2017) and the necessity of building multiracial support for BLM (Bonilla and Tillery Reference Bonilla and Tillery2020; Corral Reference Corral2020; Holt and Sweitzer Reference Holt and Sweitzer2020; Merseth Reference Merseth2018). But little is known about what white parents say or do in this domain or how they respond to minority-led social movements. Did movement activity create a focusing event that pushed progressive concepts onto the parenting agenda or did it induce backlash among the majority group? Either way, the choices that white parents make about how to introduce their children to racial politics are political acts, we argue, with both political causes and consequences that require scholarly attention. The latter half of 2020 is an especially important moment to examine regarding these political choices, not only because of widespread protest, but because the COVID-19 pandemic had forced many children into the singular care of their parents, making them arguably the primary socializing agent during this period.

We examine both whether the BLM protests in 2020 were a focusing event that connected race concepts to parenting and how these concepts manifested in white parenting practices during this period. Drawing on Google Trends and Facebook data, we show that Google searches for “how to talk to kids about race” increased by 400% in June 2020 as protest activity spiked, compared to the highest points in the preceding seven years. Further, conversations about race on Facebook parenting pages increased twelve-fold compared to the first months of 2020. These results provide clear evidence that the summer 2020 BLM protests were a focusing event that increased information-seeking on both racially progressive and reactionary dimensions, and connected race politics to parenting.

After identifying the summer 2020 BLM protests as a focusing event that connected race politics to parenting, we turn to how white parenting practices around race manifested during this unique moment in time. We surveyed a nationally diverse sample of non-Hispanic white parents with school-age children to assess the prevalence of a variety of race-related parenting choices during this period. We find that most white parents talked with their children about race in the six months following George Floyd’s murder and the majority engaged in some behavior to increase racial diversity in their children’s environment or introduce them to racial politics. But white parenting practices related to race are also rife with contradiction, implementation gaps, and divisions (see Schuman et al. Reference Schuman, Steeh, Bobo and Krysan1997; Krysan and Moberg Reference Krysan and Moberg2021; Sullivan, Eberhardt and Roberts Reference Sullivan, Eberhardt and Roberts2021). White parents often focus only on egalitarian discussion without committing to more concrete or costly actions, or display a mix of racially progressive and racially hostile behaviors in their approach. Further, the data reveal parenting practices are deeply divided by party, gender, and socioeconomic status and suggest that COVID-19 pandemic-induced increases in time spent with children likely produced unique amounts of race-related talk and practices.

Scholars often debate whether social movements matter for political outcomes, focusing on immediate, substantive policy changes (Enos, Kaufman, and Sands Reference Enos, Kaufman and Sands2019; Gillion Reference Gillion2013; Wasow Reference Wasow2020; Gause Reference Gause2022) or the impact on activists or communities heavily involved in movements (Parker and Barreto Reference Parker and Barreto2013; Pedraza, Segura, and Bowler Reference Pedraza, Segura, Bowler, Bloemraad and Voss2011; Wallace, Zepeda-Millán, and Jones-Correa Reference Wallace, Zepeda-Millán and Jones-Correa2014; Zepeda-Millán and Wallace Reference Zepeda-Millán and Wallace2014). Fewer have considered how social movements might achieve broader changes by reshaping public opinion (but see Lee Reference Lee2002; Mazumder Reference Mazumder2018; Gillion Reference Gillion2020; Reny and Newman Reference Reny and Newman2021) or by influencing how parents talk to their children about politics. Our findings clearly show that BLM forced race onto the U.S. parenting agenda in summer 2020. That some white parents engaged their children in racial politics during this period further represents a profound departure from previous findings (Abaied and Perry Reference Abaied and Perry2021; Hagerman Reference Hagerman2018; Underhill Reference Underhill2018). Still, an implementation gap in white race parenting reflects Alicia Garza’s frustrations—the racial hierarchy in the United States is robust—but generational change may be a way forward for race-based social movements.

Black Lives Matter and the Connection Between Politics and Parenting

Black feminist theorists have argued that raising a child in a nation hostile to their existence is a radical political act; it links group survival and empowerment to instilling these traits in individual children (Collins Reference Collins1990, Reference Collins, Glenn, Chang and Forcey1994). Raising a white child to adopt an antiracist approach in a world that otherwise immerses them in racial privilege may reflect a similarly deliberate political choice. Alternatively, raising a white child to perpetuate the racially unequal status quo is also political in nature. Easton and Dennis (Reference Easton and Dennis1969, 18) explain in their foundational work that theories of political socialization must have the “objective … to demonstrate the relevance of socializing phenomena for the operations of political systems.” The choices that (white) parents make about whether and how to talk to their children about race, the products they buy, and the social environment they choose to construct are precisely these types of phenomena.

The latter half of 2020 offers a unique period to consider these choices among America’s white parents for two reasons. First, this period saw unusually high levels of protest aimed at clarifying white people’s role in perpetuating racial hierarchy. On May 26, 2020, a video was released of white police officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on the neck of George Floyd, a Black man, for more than nine minutes, ultimately killing him. The video evidence of Floyd’s murder came shortly after Breonna Taylor was killed by Louisville police in her own apartment and Ahmaud Arbery was chased and killed by three white men while jogging in Georgia—events alluded to in Garza’s opening epigraph. In the wake, Black-led protests swept the country under the organizing banner, Black Lives Matter, with an estimated 15–26 million people attending and substantively high levels of white involvement (Buchanan, Bui, and Patel Reference Buchanan, Bui and Patel2020; Burch et al. Reference Burch, Cai, Gianordoli, McCarthy and Patel2020; Harmon and Tavernise Reference Harmon and Tavernise2020).

At the same time, the emergence of COVID-19 meant that America’s children were spending unusually large amounts of time with one socializing agent: their parents. Across the nation, schools, day cares, and summer camps closed as the pandemic raged, decreasing the care-taking of children by individuals other than parents, and cutting off social interactions between young people and their peers—another important source of social learning (Jennings and Niemi Reference Jennings and Niemi1974; Pietryka et al. Reference Pietryka, Reilly, Maliniak, Miller, Huckfeldt and Rapoport2018; Settle, Bond, and Levitt Reference Settle, Bond and Levitt2011; Raychaudhuri Reference Raychaudhuri2020). Others have suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic allowed BLM protests in the summer of 2020 to reach their unprecedented scale by reducing work, travel, and social obligations (Arora Reference Arora2020); it too may have meant that parents were children’s primary source in interpreting the racial politics of the moment. Large, salient incidents, like protests involving millions of people, can shape attitudes for entire cohorts of Americans (Lee Reference Lee2002; Biggs and Andrews Reference Biggs and Andrews2015; Wasow Reference Wasow2020; Reny and Newman Reference Reny and Newman2021) by promoting both recognition of a problem and the necessity of public involvement to solve it (Enos, Kaufman, and Sands Reference Enos, Kaufman and Sands2019; Kingdon Reference Kingdon1984). Even fleeting events that children and teenagers experience can offer them lifelong bases to understand the world (Sears and Valentino Reference Sears and Valentino1997; Schuman and Corning Reference Schuman and Corning2012; Sears Reference Sears and Renwick2004), aided by the interpretation of their parents (Campbell and Wolbrecht Reference Campbell and Wolbrecht2006; Valentino and Sears Reference Valentino and Sears1998).

As a result, the choices parents made about whether and how to talk to or involve their children in racial politics are important, but to date, white people’s racialized parenting choices have not been an object of sustained study. Work in other social sciences details how non-white parents prepare their children to navigate the American racial hierarchy (e.g., Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Rodriguez, Smith, Johnson, Stevenson and Spicer2006; Lesane-Brown Reference Lesane-Brown2006; Thomas and Speight Reference Thomas and Speight1999). A few recent studies use qualitative data and convenience samples to show that whites’ attitudes about race predict those of their children’s (Pahlke, Bigler and Suizzo Reference Pahlke, Bigler and Suizzo2012) and that white kids themselves engage in an interpretive process to understand race in America (Hagerman Reference Hagerman2018). But within political science, the study of parenting has focused on the dissemination of orientations like partisanship or the value of political participation (Jennings and Niemi Reference Jennings and Niemi1974; Krupnikov and Ryan Reference Krupnikov and Ryan2022; Oxley Reference Oxley, Bos and Schneider2017), and more recently, on how adults are shaped politically by their role as parents (Elder and Greene Reference Elder and Greene2007, Reference Elder and Greene2012; Glynn and Sen Reference Glynn and Sen2015; Greenlee Reference Greenlee2010; Sharrow et al. Reference Sharrow, Rhodes, Nteta and Greenlee2018; Swerdlow Reference Swerdlow1993; Washington Reference Washington2008).Footnote 1

This lacuna may reflect both the gendered nature of parenting and the traditional “invisibility” of whiteness to white people. Parenting has long been considered women’s work, with American families exhibiting durable gendered patterns in parenting labor, even as fathers begin to spend more time with their children (Bianchi, Robinson, and Milkie Reference Bianchi, Robinson and Milkie2006; Blair-Loy et al. Reference Blair-Loy, Hochschild, Pugh, Williams and Hartmann2015; Hochschild Reference Hochschild1989; Ladd-Taylor Reference Ladd-Taylor1995; Robinson and Godbey Reference Robinson and Godbey1999). This pattern may produce the belief that parenting is apolitical (cf. Oxley Reference Oxley, Bos and Schneider2017), as labor traditionally done by women is frequently relegated to the private rather than the public sphere and viewed as outside the scope of politics (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001; Cowan Reference Cowan1983; Ladd-Taylor Reference Ladd-Taylor1995).Footnote 2

Further, the institutionalization of power around whiteness has led some to claim that white people typically do not observe how whiteness shapes their lived experience (Haney López Reference Haney López2006). In political science, this often leads to the view that research on race is about understanding the identities and choices of non-white peoples or considering attitudes toward people of color rather than how white people themselves construct and reify whiteness (Segura and Rodrigues Reference Segura and Rodrigues2006, cf. Jardina Reference Jardina2019; Sides, Tesler, and Vavreck Reference Sides, Tesler and Vavreck2019). As a result, studies of how non-white people talk to their children about race are prolific (e.g., Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Rodriguez, Smith, Johnson, Stevenson and Spicer2006; Lesane-Brown Reference Lesane-Brown2006; Seaton et al. Reference Seaton, Gee, Neblett and Spanierman2018; Thomas and Speight Reference Thomas and Speight1999), with much less attention paid to white parents (Abaied and Perry Reference Abaied and Perry2021; Hagerman Reference Hagerman2018; Sullivan, Eberhardt, and Roberts Reference Sullivan, Eberhardt and Roberts2021).Footnote 3

What might white parents have done or said to their children in the summer of 2020 amid BLM activism and in the months that followed? One branch of research on the racial attitudes of adults suggests precisely nothing. White Americans’ position at the top of the racial hierarchy allows many white people to benefit from their racial identity without requiring recognition of how race affects their daily lives (Haney López Reference Haney López2006; Waters Reference Waters1990). Embracing colorblind notions of egalitarianism, many white people reason that talking about race is itself part of the problem (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2006; Engelhardt Reference Engelhardt2021c). This may lead white parents to shy away from any discussion about race with their children (Sullivan, Eberhardt and Roberts Reference Sullivan, Eberhardt and Roberts2021). Indeed, the relatively few studies of white parental discussion around race in the early 2000s use convenience samples and qualitative interviews to argue that this is the default style among America’s white parents (Abaied and Perry Reference Abaied and Perry2021; Hagerman Reference Hagerman2018; Underhill Reference Underhill2018). And yet a “race-mute” or colorblind approach to parenting is in itself a political choice that reproduces the status quo racial hierarchy (Apfelbaum et al. Reference Apfelbaum, Pauker, Sommers and Ambady2010; Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2006; Bonilla-Silva, Goar, and Embrick Reference Bonilla-Silva, Goar and Embrick2006).

Others argue that changes in the demographic landscape of the United States and demands for racial equality have renewed whiteness’ salience, leading to backlash and modern links between resentment and old-fashioned racism (Craig and Richeson Reference Craig and Richeson2014; DeSante and Smith Reference DeSante and Smith2020; Jardina Reference Jardina2019; Tesler Reference Tesler2013; Parker and Barreto Reference Parker and Barreto2013; Johnson Reference Johnson2018). Wasow (Reference Wasow2020) shows, for instance, that riots or protests where even a small number of people use violent tactics may increase white hostility. More generally, white Americans have typically organized to thwart—often violently—the advancement of racial justice (Anderson Reference Anderson2016; Johnson Reference Johnson2018; Klarman Reference Klarman1994; McRae Reference McRae2018; Valelly Reference Valelly2004; Weaver Reference Weaver2007). Such backlash may manifest in some white people’s parenting choices. They may, for instance, discuss race by emphasizing that others do not uphold (white) American values (Kinder and Sanders Reference Kinder and Sanders1996; Parker and Barreto Reference Parker and Barreto2013).

A final literature on white racial attitudes suggests the demography of America has already changed enough that a new coalition-building politics exists between white people and racial minorities (Pérez Reference Pérez2021). Many white Americans report feeling sympathy for racial minorities (Chudy Reference Chudy2021) and guilt about discrimination their group has engaged in (Chudy, Piston, and Shipper Reference Chudy, Piston and Shipper2019); each is associated with support for restorative policies (see also Lee Reference Lee2002). Alongside these affective responses, an increasing share of whites acknowledge structural discrimination (Engelhardt Reference Engelhardt2021b), and many on the political left express concern with group-based experiences and value multiculturalism and diversity (Citrin and Sears Reference Citrin and Sears2014; Engelhardt Reference Engelhardt2021c). Black-led movement activism may stimulate this branch of concerns among some white Americans, facilitating coalition-building around race progressivism (Benjamin Reference Benjamin2017; Cortland et al. Reference Cortland, Craig, Shapiro, Richeson, Neel and Goldstein2017; Thurston Reference Thurston2018).

Further, social movements often work by changing norms about what is acceptable, good, and right in society (Omi and Winant Reference Omi and Winant1994), with the American civil rights movement, for instance, leading most white people to endorse explicit racial egalitarianism (Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001). BLM has argued that in addition to racial egalitarianism, Americans need to confront systemic racism and challenge white supremacy if racial justice for Black people is to be achieved. This includes white Americans embracing the concept of antiracism, a term popularized by Ibram Kendi but one reflecting a larger and longer tradition in scholarly work on race (e.g., Haney López Reference Haney López2006; Kendi Reference Kendi2016, Reference Kendi2019; Lipsitz Reference Lipsitz2006). For white Americans, this means consciously unlearning racism, acknowledging bias and privilege, and dismantling white supremacy. Like past social movements (Andrews and Biggs Reference Andrews and Biggs2006; Biggs and Andrews Reference Biggs and Andrews2015; Gillion Reference Gillion2020; Lee Reference Lee2002; Mazumder Reference Mazumder2018; Thurston Reference Thurston2018; Wasow Reference Wasow2020), BLM can act as a teacher, introducing concepts to which the public responds (Sullivan, Eberhardt, and Roberts Reference Sullivan, Eberhardt and Roberts2021). If parents want their children to be good and moral, they may alter their parenting practices as norms change.

But even antiracism efforts can fail to seriously address discrimination if white people prioritize their emotional needs rather than engage in more costly activism work that seeks political, social, or economic change (Hughey Reference Hughey2012). Support for colorblind ideology and a denial of systemic discrimination may further intersect with the more empathetic and affective responses, leading to ambiguity and conflict in white racial attitudes and their manifestation in explicit race-focused parenting. While the summer 2020 protests may have set an agenda that forced white parents to introduce racial politics to their children, parents still needed to navigate how, exactly, to do this. As a result, we may observe implementation gaps between discussion of race progressive concepts and more costly follow-through.

With these themes in mind, we investigate three interrelated research questions: was the BLM activism in the summer of 2020 a focusing event that pushed racial politics onto the agenda of (white) parents? What did race-related parenting choices look like among white people with school-aged children during this unique moment? And which characteristics of white parents associate with different types of parenting responses? Collectively, these questions help us establish what race-related parenting looked like at a consequential moment for the nation’s ongoing racial project.

Protests in Summer 2020 as a Focusing Event

We turn first to determining whether the deaths of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd and the subsequent BLM protests constitute a focusing event that drew Americans’ attention to race and connected race-related topics to parenting. We use data from Google Trends and Facebook parenting groups to explore if public interest in racialized concepts changed during this period and whether this information seeking was tied to parenting. Increased interest would suggest the occurrences in late spring and summer 2020 were indeed focusing events that oriented public attention toward race and created a unique period for considering white people’s racial parenting choices.

Using publicly available Google Trends data, we examine the search incidence in the United States of seven terms: “Black Lives Matter,” “racism,” “antiracism,” “white privilege,” “looting,” “rioting,” and “how to talk to kids about race.” The first two search terms encompass general themes from the protests in summer 2020; the second two (antiracism, white privilege) focus on white in-group responsibility for racial inequality; the next two (looting, rioting) are concepts shown by others to be racialized and tied to backlash responses to minority-led movements (Jacobs Reference Jacobs2000; Johnson, Dolan, and Sonnett Reference Johnson, Dolan and Sonnett2011; Wasow Reference Wasow2020); and finally, the last topic (how to talk to kids about race) allows us to look for the coupling of race themes with parenting.

We do not view these terms as definitive of all possible race-related topics, but rather suggestive of information seeking on various race-related dimensions. We use these terms in the same way scholars studying race-related speech employ key words: terms that are more likely than not linked with race explicitly or implicitly (Engelhardt Reference Engelhardt2021c; Gillion Reference Gillion2016; Reny and Newman Reference Reny and Newman2021). Although we are unable to determine the valence of search intention from these words and certainly cannot include the universe of all possible terms, the selected phrases allow us to explore how information seeking on various race subjects changed over time in conjunction with movement activism.

We explore the popularity of these search terms in the United States from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2020. This eight-year period encompasses the creation of the BLM hashtag in July 2013 and continues for seven months following Floyd’s murder on May 25, 2020. Figure 1 shows our results, displaying changes in the popularity of each search term over the seven-year period. The x-axis shows time in months and the y-axis represents popularity of searches for each term. A score of 100 denotes peak search term popularity during the period and 0 represents points with insufficient searches for the term to produce a data point.

Figure 1 Google search term popularity in the United States

The top panel of figure 1 displays results for the search term, “Black Lives Matter.” The time trend shows that Americans’ interest in the term peaked in June 2020, shortly after the death of George Floyd and amidst thousands of protests nationwide. Compared to this high point, search incidence was much less frequent in the preceding period despite important movement activism. For instance, July 2016 was the second most frequent search period, likely induced by police officers killing Alton Sterling and Philando Castile and the ensuing discussion about whether BLM caused gunmen to kill police officers in Dallas and Baton Rouge. Still, search incidence during this period was only 31% of what it was in July of 2020, four years later.

The general pattern of searches for “Black Lives Matter” is mirrored in the remaining panels, which all show large increases in public interest around racialized concepts during this period. Race-progressive concepts central to movement rhetoric like “racism,” “antiracism,” and “white privilege” all peak in June 2020 with popularity remaining higher throughout the summer months than in the preceding seven years.Footnote 4 But the two terms associated with racial backlash, “looting” and “rioting,” also follow a parallel trend. This suggests that as Americans sought out information about race-progressive concepts, they also were engaging with reactionary interpretations of movement activity (e.g., Engelhardt Reference Engelhardt2021c; Parker and Barreto Reference Parker and Barreto2013; Wasow Reference Wasow2020). Collectively, the findings suggest that the events of summer 2020 were indeed a focusing event that stimulated information-seeking in both progressive and reactionary directions.

In the last panel in figure 1’s second row, we turn to examining explicitly whether this focusing event tied race to parenting. The data offer a similar pattern for the search term, “how to talk to kids about race.” Popularity peaks in June 2020 with scores rarely rising above twenty in the preceding period.Footnote 5 We explore this connection further by examining the incidence of race-related posts on Facebook’s public parenting pages using CrowdTangle. CrowdTangle describes itself as a Facebook-owned tool to track content and interactions on public Facebook pages and profiles. CrowdTangle creates and maintains lists of public pages by topic such as business news, beauty brands, and health and fitness. From CrowdTangle’s preconstructed list of 225 public parenting pages, we searched for posts including at least one of the following six search terms: black lives matter, racism, diversity, antiracism, antiracist, and privilege. We do so for a period covering the three months before and after George Floyd’s murder on May 25, 2020.Footnote 6 Again, we do not view this list as exhaustive but rather suggestive of the types of posts potentially connected to (white) race-related parenting choices and their variation over time.

The first panel of figure 2 shows the count of daily mentions for these terms, pooled together, during this six-month period. Race-related terms spike considerably on Facebook parenting pages in June 2020, mimicking the Google Trends data. There are twelve times as many mentions of racial topics in the three months after Floyd’s death compared to the three months prior. Even as relevant posts decline after this initial peak, mentions of race-related terms remain higher than before Floyd’s death. This pattern replicates for each term individually. For example, prior to Floyd’s death on May 25 our data contain one instance of the term “antiracist” and none for “antiracism” (refer to online appendix A for disaggregated plots).

Figure 2 Mentions of race-related topics in public Facebook parenting groups

Note: Left-hand plot shows mentions of antiracism, antiracist, black lives matter, diversity, privilege, and racism. Right-hand plot shows mentions of sleep, bedtime, nap, wake, crib, bed.

Data source: CrowdTangle 2021.

In the second panel of figure 2 we provide the distribution for a placebo topic: sleep. This plot shows mentions of the words: sleep, bed, bedtime, crib, wake, and nap—important topics for parents—from the same 225 public parenting pages. The comparison provides a test of the relative magnitude of race-related topics during the periods before and after Floyd’s murder and the emergence of widespread protest. We find that throughout April, sleep-related posts were much more frequent than race-related posts. There was an average of 11.3 posts per day about sleep compared to 1.1 posts per day about race. In June, the frequency of sleep topics remains stable at 10.8 per day, but race-related posts increase substantially to 32.6 posts per day. This suggests the increased number of posts in our race topics category does not reflect a broader change in the volume of activity on these pages during the summer, but rather is indicative of increased attention specifically to race on parenting pages.Footnote 7

Although exploring only a small set of terms, our Google Trends and Facebook data suggest that the 2020 protests were focusing events that increased attention to race in both progressive and reactionary directions. More specifically, the summer activism pushed these ideas onto the parenting agenda, appearing on ostensibly race-neutral parenting pages. This discussion included concepts that explicitly implicate white people, reflecting the rhetoric of Black activists and suggesting that these ideas might appear in white parents’ choices during this period. Considering this, we next turn to examining what, exactly, explicit race socialization looked like among white parents during this unique moment in time.

White Race-Parenting in the Latter Half of 2020

Does the increased interest in race and parenting we find online manifest in observable actions among white parents? To examine this question we conducted an original survey in December 2020 using the online platform Lucid. Participants were parents who identified as only non-Hispanic white and indicated they had at least one only-white child between the ages of 5 and 17—a critical period for racial attitude development (Aboud Reference Aboud1988; Goldman and Hopkins Reference Goldman and Hopkins2020).Footnote 8 We quota sampled on the dimensions of gender, age, and geographic region to create a sample approximating the white parenting population in the United States.Footnote 9 Our final sample includes 1,083 respondents. We refer to this study here as the Racial Parenting Survey (RPS).

The RPS included four batteries designed to assess whether and how white parents talked with their school-age children about race in the latter half of 2020 and actions they might have taken to expose their children to diversity, racial politics, and concepts of white privilege. RPS respondents were asked to consider their parenting choices “since May 2020,” capturing race-related talk and behaviors for a roughly seven-month window encompassing the emergence of wide-scale BLM protests in late-spring and summer of 2020. We include a specific time bound for this task to facilitate recall (Krosnick and Presser Reference Krosnick, Presser, Wright and Marsden2010).Footnote 10

The first battery of questions in the RPS focuses on discussion topics. Our measures capture three possible responses to movement demands in 2020: colorblindness, backlash, and racial progressivism. We draw from existing work on racial socialization, colorblindness, resentment, and white privilege (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2006; Hagerman Reference Hagerman2018; Hughes and Chen Reference Hughes and Chen1997; Kinder and Sanders Reference Kinder and Sanders1996; Pahlke, Bigler and Suizzo Reference Pahlke, Bigler and Suizzo2012) to build measures capturing discussion about both ingroup and outgroup experiences regarding racial bias, privilege, work ethic, multiculturalism, and egalitarianism. This battery captures both right-leaning rhetoric about the socio-cultural status of Black Americans in the United States today, more moderate concepts of egalitarianism, and left-leaning beliefs about white privilege. This thematic breadth not only reflects diversity in public opinion research, it captures variation in how political elites discuss race (Engelhardt Reference Engelhardt2021c), which should have implications for parenting conversations.

Presented in randomized order, respondents were asked to report, “how often, if at all, you talked with your child(ren) about the following topics since May 2020:”

-

1. People are equal, regardless of their race or ethnic background.

-

2. About important people in the history of other racial or ethnic groups.

-

3. People from other racial or ethnic groups are sometimes still discriminated against because of their race or ethnicity.

-

4. About the rewards or special privileges that might come from being white.

-

5. White people get ahead because they work harder than other groups.

-

6. If Black people were more respectful to the police, things would go better for them.

-

7. About the possibility that some people might treat him or her badly or unfairly because of our race or ethnicity.

Response options ranged from “never” to “several times (4+)” with two options in between.

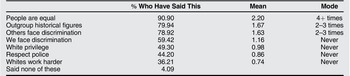

Table 1 presents the percentage of parents who report that they spoke with their children about each topic at least once, along with the mean frequency and modal response category. The most common discussion topics concern egalitarianism and outgroup experiences (see also Sullivan, Eberhardt, and Roberts Reference Sullivan, Eberhardt and Roberts2021). Ninety percent of white parents report telling their children at least once during this period that all people are equal with the modal response situated at four or more times.

Table 1 Conversations with children since May 2020

Close behind egalitarianism in prevalence are discussion topics related to explicitly out-group themes. Nearly eight in ten white parents (80%) report talking with their children about important people in history who are not white during this period and 79% said they discussed how people from other racial and ethnic groups still face discrimination. A smaller but still substantial number of parents report explicitly discussing in-group white privilege with their kids during this period (49%).

Qualitative and convenience samples on race talk preceding this period suggest that white parents are typically race-mute or race-neutral when it comes to discussing race with their children, even when the broader political environment focuses on race (Abaied and Perry Reference Abaied and Perry2021; Underhill Reference Underhill2018).Footnote 11 With over three-quarters of white parents reporting engaging in egalitarian and outgroup focused discussion, and half proposing the existence of white privilege to their children, our data suggest the latter half of 2020 may have indeed marked a unique moment in time for race-progressive talk among white parents.

Still, the data reveal evidence of widespread racial backlash talk among white parents during this period as well. The majority of respondents (59%) report telling their children that they, themselves, may face racial or ethnic discrimination. Close to half of respondents (44%) told their kids that if Black people were more respectful of police, “things would go better for them,” and over one-third reported telling their children that white people get ahead because they work harder. Although discussion of these topics was less frequent than egalitarianism and outgroup experiences with discrimination, between one-third and one-half of our sample engaged in these discussions with their children.

The relatively common discussion of both racially progressive and regressive concepts suggest widespread ambivalence may have manifested in white parenting practices during this period. For instance, 39% of respondents report talking with their children about how non-white people continue to face discrimination in the United States and also that Black people should show more respect to the police. Similarly, 32% report proposing the existence of white privilege to their children while also mentioning that white people get ahead because they work harder. This type of conflict is consistent with political behavior research showing more uncertainty than consistency among the public (Gonzalez Reference Gonzalez2020; Alvarez and Brehm Reference Alvarez and Brehm2002). The data suggest that as some white parents moved from “race mute” to engaging in more explicit racially progressive talk, their discussions demonstrated both progressive concepts advanced by the BLM movement and racially regressive language.

Talk is not the only option white parents had to teach their children about race during this time period. Alongside discussion topics, we examine race-related parenting choices around entertainment, social environment, and racial politics. Over three batteries, RPS respondents reported whether they had completed various acts since May 2020. This included: choices made to diversify children’s environments; purchases made with race in mind; and attending educational or political events related to race, such as bringing one’s child to a BLM protest.Footnote 12 Our measures capture a range of high- and low-cost behaviors that allow us to assess the degree to which racial talk themes align with follow-up actions. Reflecting Garza’s opening call upon white people to “get to business,” we assess the degree to which white parents changed their children’s exposure to racial diversity, themes of discrimination, and racial political actions directed at change away from the status quo. We note that in this battery of questions, our measures are focused primarily on race-progressive action. Taking a child to a Proud Boys rally, for instance, would also represent a form of racial socialization, but it is not one that our measures capture.

Table 2 shows the percentage of parents who report engaging in each of these twelve actions. Of our twelve measures, the most common is watching a movie or television show with one’s child because it featured non-white characters—but less than half of parents (41%) report doing this. Buying or borrowing toys or books with non-white characters or that focus on important figures in history who are not white is next, with about one-third of white parents reporting this. Less than one-fifth of parents report more costly actions like: acquiring books to teach them how to discuss racism; bringing their child to community meetings about policing or to a BLM protest; attending antiracism workshops with their child or alone focused on antiracist parenting; or changing their child’s school or daycare to place them in a more racially diverse environment. The results suggest that as the costliness of the behavior rises, fewer parents report engaging in it.

Table 2 Parenting behaviors since May 2020

Compared to race talk, explicit behaviors around racial parenting are less common. While only 4% of parents reported engaging in zero of our racial discussion measures, nearly 30% of parents say they took none of the actions we measured. This finding reveals a possible implementation gap. Even as white Americans professed egalitarian values to their children, many did not act on these beliefs (Schuman et al. Reference Schuman, Steeh, Bobo and Krysan1997; Krysan and Moberg Reference Krysan and Moberg2021). This is especially the case as actions got more costly, contentious, or inconvenient. This implementation gap may reflect, in part, the ambiguity we observed in talk themes; as conflict in individuals’ attitudes increases, paralysis in action is likely to follow (Alvarez and Brehm Reference Alvarez and Brehm2002). Still, a meaningful minority of white parents engaged in multiple race-progressive actions during this period. We find a little more than one-quarter (27%) of white parents report engaging in least five behavioral choices directed at race-progressive parenting in the latter half of 2020.

Dimensions of Variation in White Racial Parenting

Among white parents, who was more likely to engage in costly race-parenting? Who discussed antiracism with their children and who suggested that Black Americans were responsible for their own plight? We consider how three types of variables help us predict variation in white parenting choices like these: demographics including social context, characteristics of family structure, and political attitudes.Footnote 13 These variables represent important sources of cleavage in American society within and across racial group and may help us disaggregate white parents into more telling sub-populations.

For demographics, we examine respondent age, sex, education, and income. We also consider zip-code level demographics: the proportion of a respondent’s zip code that is white, is Black, has at least a four-year college degree, and its median income.Footnote 14 For family characteristics, we examine whether respondents have multiple children, the age of their oldest child, whether they are a stay-at-home parent, and how much time respondents devote to child care responsibilities daily (ranging from under 1 hour to over 12 hours). We also include measures for whether respondents reported reduced work hours or leaving the workforce due to the COVID-19 pandemic. For political attitudes, we examine partisanship and ideological self-identification. All predictors are scaled from 0–1.

To understand whether and how these factors contributed to parenting decisions in the latter half of 2020, we estimate linear models regressing the racial parenting behaviors from the previous section on our demographic, family characteristic, and political attitude predictors. This specification allows us to investigate patterns across parenting practices and whether certain correlates are consistently relevant. To facilitate these comparisons, we present the results visually in figure 3, and report full parameter estimates in online appendix D. In the plot, the columns show the relationship between each predictor and a single outcome measure, while the rows show patterns across outcomes for a given correlate. We shade the cells according to the magnitude and direction of the estimated regression coefficients. Darker cells with black outlines (coded orange in color copies) denote larger, negative coefficient estimates. Darker cells without outlines (coded purple in color copies) denote larger, positive coefficient estimates. Weak shading indicates smaller effects, with white cells denoting effects near 0. Finally, we report whether the estimates are statistically significant (p < .05) with stars.

Figure 3 Correlates of parenting decisions

Note: *p < .05. Bolded black boxes indicate negative coefficient estimates.

Considering individual demographics first, gender and education are most consistently related to parenting choices. Education predicts both higher levels of backlash talk and discussion of white privilege, along with many race-progressive actions. That is, more educated white Americans are more likely to suggest to their children that white people get ahead because they work harder and that things would go better for Black Americans if they showed more respect to the police. At the same time, they tell their children that white people experience special rewards and privileges because of their race and were more likely to accompany their children to a BLM protest and even change their child’s social environment for one with more racial diversity.

Like education, gender has statistically significant relationships with most parenting choices. White women are less likely than white men to engage in racially regressive talk where themes dwell on how Black Americans might do better if they acted more like white people and how white people are discriminated against (Kinder and Sanders Reference Kinder and Sanders1996; Kendi Reference Kendi2016). But white mothers are also significantly less likely than fathers to engage in most parenting actions. For instance, fathers are more likely than mothers to take their child to a BLM protest, attend a community meeting about race or policing, and help their children make a BLM sign.

This gender division in parenting choices may reflect both the gendered nature of the political sphere—where politics remains predominantly “men’s work”—and patterns in child-rearing responsibilities. When mothers spend time with their children, this time is disproportionately consumed by routine tasks such as bathing and feeding that meet children’s immediate daily needs. In contrast, fathers spend proportionately more time on what they view as fun types of child care, such as teaching and playing (Robinson and Godbey Reference Robinson and Godbey1999; Bianchi, Robinson, and Milkie Reference Bianchi, Robinson and Milkie2006). Talking about race, providing children with diverse entertainment, and bringing children to activism events may fall into this latter category, meaning fathers may devote more time to race-related parenting, despite spending less time with their children overall. So, while the regression adjusts for differences in self-reported child care time, we find the content of that time entails different actions for men and women in our sample.Footnote 15

The results also show relatively few significant relationships between geographic context and parenting practices. Respondents in more predominately white zip codes were less likely to attend a BLM protest with their child or assist them in making a yard sign supporting the movement. This reverses for parents living in neighborhoods with higher on-average education levels. Respondents in more homogeneously Black zip codes were more likely to purchase books featuring non-white people or change their child’s school, daycare provider, or regular place of play for one with more non-white people.

Within family structure, age of oldest child has a positive and statistically significant association with discussion around discrimination—both experienced by the ingroup and outgroup—and purchasing or borrowing books about discrimination. Parents with older children were also more likely to attend an antiracism workshop with their child and accompany their child to a BLM protest. Hours spent on child care, further, has statistically significant relationships with almost all outcomes. White parents who reported spending more time with their children were, on average, more likely to talk about egalitarianism and important individuals in history who are non-white; engage in racially resentful and backlash talk; and take actions to expose their children to diversity, multiculturalism, and racial politics.Footnote 16

Collectively, these relationships suggest widespread uncertainty in white Americans’ parenting choices (Alvarez and Brehm Reference Alvarez and Brehm2002). Variables that predict more progressive race talk and actions also commonly relate to higher levels of racially resentful or backlash talk. Our data suggest that white parenting on race during this period was marked by complex and often conflicting choices among many who chose to engage in race talk at all.

The results also suggest that racial parenting practices may have looked very different if not for the pandemic. Parents who reduced their work hours or left the workforce due to COVID-19 were more likely than those whose employment situations were unaffected to report engaging in race-focused parenting. While differences for those who left the workforce are only reliably different from zero when considering out-group focused talk, those with reduced work hours have statistically significant increases on most talk and behaviors. This includes both resentful and in-group talk, as well as purchasing products with diverse characters and attending anti-racist parenting workshops, BLM protests, and community meetings. With many children out of school and without organized activities during this time period, parents were often forced to spend significantly more time with their children. This increase in parenting hours induced by COVID-19 appears to have increased the frequency of active race socialization.

Our last set of covariates focus on political attitudes, which show clear divides in race socialization practices depending on white parents’ partisan and ideological affinities. Republican parents are less likely than Democrats to talk with their kids about white privilege and self-identified conservatives are less likely to talk about how non-white people continue to experience discrimination or about important historical figures who are non-white. Right-leaning partisanship and ideology also predict lower levels of engagement in a host of race-progressive parenting activities including attending a BLM protest with a child or community event about race or policing, changing a child’s social environment for one with more diversity, or reading books about outgroup history or experiences with discrimination. Racially polarized party politics appears to extend beyond electoral politics and public opinion to reported parenting choices.

While we see these results as informative about how parenting decisions associate with different individual characteristics, some may wonder whether this modeling strategy artificially downplays the contribution some correlates make. Our political attitudes may, for instance, channel some of the contribution demographics make, underselling the latter’s total influence. Likewise, one might ask whether the relationships between gender and parenting choices differ if family structure variables were excluded from our models. To examine this, we report results in online appendix D from a series of models sequentially adding predictor sets. The findings show little change in relationships between correlates and racial parenting when analyzed using this sequential approach.

Next Steps in the Study of Race and Parenting

The evidence suggests that the 2020 BLM protests served as a focusing event that drew national attention to racial concepts; we see substantial spikes in Google searches and Facebook parenting posts about race in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder. Our original survey shows that most white parents during this time period discussed race with their children and nearly three-quarters took some kind of race-progressive action to increase diversity in their child’s environment or expose them to racial politics. But our results are also rife with contradiction (Alvarez and Brehm Reference Alvarez and Brehm2002; Converse Reference Converse and Apter1964; Gonzalez 2021): many white parents engaged in both racially progressive and racially regressive talk during this period. Further, much of racial parenting appears expressive: as costliness of actions increased, behaviors consistent with beliefs declined.

Our findings in many ways support Garza’s opening claim that the majority of white Americans in the summer of 2020 engaged in actions that were low-cost, focused on moderate aims, or reflected ambivalence. Garza is not the first movement leader to be frustrated by such outcomes. In Reference King1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote from a Birmingham jail cell, “I must confess that over the last few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate … Shallow understanding from people of goodwill is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will.” While the BLM movement clearly pushed race onto the agenda of many white parents, “shallow understanding” was the behavioral expression that most passed along to their children. As with the American Civil War, the Civil Rights Movement, and Obama’s watershed election (Alexander Reference Alexander2010, Omi and Winant Reference Omi and Winant1994, Tesler Reference Tesler2016), BLM activity may have disrupted the American racial hierarchy but it did not obliterate it. The question of how race socialization may facilitate this disruption, though, and perpetuate change over generations demands more study.

Some may worry that demand effects and social desirability limit the precision of our findings. If respondents guess the survey’s purpose or are influenced by a sense of normative expectations, our estimates may incorrectly gauge the nature and variety of parenting decisions. For instance, our survey asks respondents to think of the period since May 2020. While facilitating recall (Krosnick and Presser Reference Krosnick, Presser, Wright and Marsden2010), this wording may also distort responses by priming the summer events and produce misreporting based on perceptions of what is thought of as normatively appropriate. Recent work offers little evidence for at least experimental demand effects around race (Mummolo and Peterson Reference Mummolo and Peterson2019) and white Americans continue to offer meaningful responses to explicit racial attitude items, suggesting minimal social desirability concerns (Axt Reference Axt2018; Engelhardt Reference Engelhardt2021a). Indeed, a significant portion of our respondents admit to backlash talk and few claim to have performed costly progressive actions, alleviating at least the largest concerns that our results are driven entirely by deliberate misreporting. Still, our data may highlight what whites see as socially acceptable—capturing changing racial norms more so than actual behavior. These norms, though, are themselves a vehicle for behavior change (Tankard and Paluck Reference Tankard and Paluck2016). From this perspective, there is virtue in virtue signaling, with recognition a first step to behavior modification (Zaki and Cikara Reference Zaki and Cikara2020).

We note, too, that our data do not allow us to measure how children interpret their parents’ behaviors. Children are themselves actors in the process of race learning, deciphering, asking questions, and observing their world in ways that our design cannot assess (Hagerman Reference Hagerman2018; Hatemi and Ojeda Reference Hatemi and Ojeda2021). While even brief events, if salient enough, can have long-term consequences on cohort attitudes (Sears and Valentino Reference Sears and Valentino1997; Schuman and Corning Reference Schuman and Corning2012; Sears Reference Sears and Renwick2004), it remains to be seen if this summer of protests will be such a long-term force. The attitudes of children are beyond the scope of this article, but future attention to the politics of parenting choices should consider how social movements, including Black Lives Matter, may shape the choices parents make and, in doing so, influence the political world over generations to come.

Omi and Winant (Reference Omi and Winant1994) argue that the racial project of the United States is always in flux, with forces working to uphold and others to challenge the racial order set in motion hundreds of years ago. Summer 2020 was a unique moment in time, marked by massive Black-led protests and coupled with a global pandemic, that likely affected the choices of white parents and encouraged them to talk about race at rates higher than in recent decades. And yet the next racial project—possibly represented by the rise in parental activism to strike “critical race theory” from school curricula—is likely right around the corner. Our Facebook and Google Trends analyses indicate that drop-off occurred in race discussion and information-seeking following their summer 2020 peaks. Did it emerge again in the summer of 2021 as white people flooded school board meetings with anti-critical race theory signs? We must continue to study how parents talk about race and create their children’s racial environments if we want to understand both the short-term and long-term effects social movements have on the American political landscape.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592722001050.

A. Crowd Tangle Data

B. Lucid Sample Information

C. Survey Questions

C.1 Filtering Questions

C.2 Racial Socialization Questions

C.3 Covariates

D. Model Results for Parenting Correlates

E. Family Structure’s Conditional Effect by Gender

Acknowledgement

The authors are are grateful to participants of the RIPS lab at Vanderbilt University, members of the Political Science Department at University of Pittsburgh, Cindy Kam, Efrén Pérez, anonymous reviewers, the special edition’s editor Christopher Parker, and the editors at Perspectives on Politics for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. Funding for the Racial Parenting Survey was provided by Vanderbilt University.