Child safeguarding has never been as starkly topical as now, following the media's indignation at the failures of various professionals to protect vulnerable children (e.g. Baby Peter and Khyra Ishaq), despite the apparent lessons from the tragic case of Victoria Climbié. This media focus on safeguarding children and the multitude of subsequent reports and guidelines are changing the perspective of adult mental health services about their responsibilities to their patients’ children. It is estimated that 30% of adults with a mental illness have dependent children and that about a third of children who live with a parent who has a mental illness ‘will themselves develop significant psychological problems or disorders’.Reference Mayes, Diggins and Falkov1 Although in the majority of cases of child abuse there is no known history of parental mental health problems, professionals are often judged in retrospect following serious adverse outcomes. Because of this there is a growing recognition of the importance of screening for child protection issues in adult psychiatry patients, and some mental health trusts have made it mandatory to record the details of all children in close contact with all psychiatric patients.

There have been studies investigating parenting and child safeguarding for adult patients with a variety of disorders, most notably borderline personality disorderReference O'Daly2 and intellectual disability,Reference Dowdney and Skuse3 but also schizophrenia,Reference Ramsay, Howard and Kumar4 bipolar affective disorderReference Venkataraman and Ackerson5 and depression.Reference Famularo, Barnum and Stone6 Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a developmental psychiatric disorder typified by a constellation of symptoms starting in childhood and frequently continuing into adult life.Reference Murphy and Barkley7 We acknowledge that the concept of adult ADHD has been criticised on nosological and pharmacological grounds.Reference Moncrieff and Timimi8 The DSM-IV-TR criteria for ADHD include symptoms from the classic triad of inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity.9 Symptoms that may specifically affect parenting skills include anger management difficulties, distractibility, and problems with concentration, memory and organisation. Furthermore, significant impairment of educational, relationship and occupational functioning is associated with ADHD.Reference Murphy and Barkley7 We consider the effect of parental ADHD on children, and examine how to apply UK national guidelines on child safeguarding to adult psychiatry.

Adults with ADHD and safeguarding children

The following characteristics of ADHD provide the justification for an increased interest in child protection issues.

Prevalence

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder is a common disorder that begins in childhood. Childhood prevalence rates of 3–7% have been reportedReference Barkley and Barkley10 and research evidence estimates a prevalence in adulthood of 2.5–4.4%.Reference Simon, Czobor, Bàlint, Mészáros and Bitter11,Reference Kessler, Adler, Barkley, Biederman, Conners and Demler12 The increased demands of adult life can expose ADHD-related impairments, such as occupational and social difficulties and mood lability, which were not obvious or relevant in childhood. The disorder often remains unrecognised in women as the symptoms can be less overt than in men.Reference Quinn13 Also, females with adult ADHD may present with greater levels of emotional dysregulation, affective symptoms, sleep problems and past DSM-IV Axis I disorders than their male counterparts.Reference Robison, Reimherr, Marchant, Faraone, Adler and West14

Heritability

With heritability estimates of around 76%,Reference Faraone, Perlis, Doyle, Smoller, Goralnick and Holmgren15 the offspring of people with ADHD are likely to have ADHD themselves, and therefore be more challenging to parent effectively. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines state: ‘Because of the increased rates of ADHD among close family members, many have children with ADHD, and need additional help to provide effective support for their children’ (p. 34).16

Children with the symptoms of ADHD – even those with asymptomatic parents – are at greater risk than their peers of abuse (physical, neglectful and sexual). The severity of the reported abuse has been found to be proportionate to the number of specifically inattentive symptoms that such children exhibit.Reference Ouyang, Fang, Mercy, Perou and Grosse17

Treatability

Once recognised and diagnosed, ADHD is a highly treatable condition. Treatments include pharmacotherapy and psychosocial interventions.16

Comorbidity

Antisocial personality disorder, conduct disorder, anxiety disorders and affective disorders have all been shown to be more frequent in adults with ADHD.Reference Biederman, Faraone, Spencer, Wilens, Norman and Lapey18,Reference McGough, Smalley, McCracken, Yang, Del'Homme and Lynn19 Affective disorders with greater incidence in adults with ADHD include: major depressive disorder (67%), dysthymia (23%) and bipolar disorder (17%).Reference Millstein, Wilens, Biederman and Spencer20 Drug misuse in parents is another factor increasing the risks to children,21,22 making the higher rates of substance use disorders found in adults with ADHD germane to child safeguarding.Reference Murphy and Barkley7,Reference Biederman, Faraone, Spencer, Wilens, Norman and Lapey18,Reference McGough, Smalley, McCracken, Yang, Del'Homme and Lynn19

Finally, comorbidity with other neurodevelopmental disorders carries obvious additional child protection-related risks. Autism traits often coexist with hyperkinetic symptoms, and it is estimated that 0.5% of young adults would show the combination of ADHD and autism-spectrum disorders.Reference Gillberg, Gillberg, Anckarsäter, Råstam, Buitelaar, Kan and Asherson23 With regard to comorbidity of ADHD with intellectual disability, prevalence rates of 15% have been reported.Reference Xenitidis, Paliokosta, Pappas, Bramham, Buitelaar, Kan and Asherson24

Forensic issues and domestic violence

The high prevalence of childhood (50%)Reference Young, Gudjonsson, Wells, Asherson, Theobald and Oliver25 and ongoing adult (21.7%)Reference Retz, Retz-Junginger, Hengesch, Schneider, Thome and Pajonk26 ADHD in prison populations, taken together with greater recidivism and violent behaviour in offenders who have ADHD,Reference Satterfield and Schell27 might suggest a causal link between ADHD and criminality – perhaps because of high impulsivity. However, the association between childhood ADHD and later criminality is thought to be entirely dependent on the presence of comorbid childhood conduct disorder.Reference Satterfield, Faller, Crinella, Schell, Swanson and Homer28,Reference Mannuzza, Klein, Konig and Giampino29 Despite this, it remains important to carefully consider past criminal and conduct problems in adults with ADHD.

There may be a higher rate of ADHD in perpetrators of domestic violence, but there is insufficient evidence to suggest that ADHD is responsible for this – other factors may confound.Reference Mandell30 Parents who have been either the perpetrators or recipients of violence may struggle to meet the needs of their children, and childhood exposure to domestic violence is associated with high risks for ‘developing emotional and behavioural problems’.21

Impact of ADHD on parenting capacity

By its nature, ADHD makes it difficult for parents to be organised, consistent and to maintain attention when supervising their children.Reference Weiss, Hechtman and Weiss31 In women, ADHD is associated with having more sexual partners and experiencing a pregnancy at a younger age.Reference Barkley and Barkley32 In general, adults with ADHD are more likely to experience divorce and separation,Reference Biederman, Faraone, Spencer, Wilens, Norman and Lapey18 as well as multiple marriages,Reference Murphy and Barkley7 and therefore their children will be exposed to greater instability in family structure. Such adults are also likely to have poorer academic qualifications, a greater likelihood of being an unskilled worker, have more unstable work records with more frequent changes in job, poorer occupational performance and a greater likelihood of impulsively leaving a job or being sacked.Reference Murphy and Barkley7,Reference McGough, Smalley, McCracken, Yang, Del'Homme and Lynn19 These social impairments are relevant because maternal youth, poverty, poor maternal education, poor marital quality, parental conflict, low paternal involvement, single parent status and low self-esteem have all been associated with neglectful parenting.Reference Brown, Cohan, Johnson and Salzinger33

The challenges to parenting from adult ADHD are present even before giving birth, with expectant mothers more likely to be unmarried, their pregnancy to be unplanned and their attendance at prenatal check-ups to be poorer.Reference Ninowski, Mash and Benzies34 Given that ‘even prior to any contact with their infant, women with ADHD symptoms have maladaptive cognitions regarding their expectations of motherhood and parenting abilities’ (p. 54),Reference Ninowski, Mash and Benzies34 it is hardly surprising that they develop ‘lower parenting self-esteem, a more external parenting locus of control, and less effective disciplinary styles’ (p. 28).Reference Banks, Ninowski, Mash and Semple35

Even adults without ADHD find being a parent of a child with ADHD very challenging. In general, parents of children with significant aggressive-hyperactive-impulsive-inattentive behaviours are likely to feel less satisfied, more stressed and less efficacious in their parental role than parents of children who do not have ADHD,Reference Shelton, Barkley, Crosswait, Moorehouse, Fletcher and Barret36 and report a lower quality of life than the general population.Reference Xiang, Luk and Lai37 Owing to the high heritability of the condition, parents with ADHD commonly have children with the condition, and this can be particularly challenging for families. In general, self-reported inattention in the parents of children with ADHD may be associated with lax parenting.Reference Harvey, Danforth, McKee, Ulaszek and Friedman38

There is evidence that mothers and fathers with ADHD interact with their children who also have ADHD in different ways.Reference Harvey, Danforth, McKee, Ulaszek and Friedman38–Reference Psychogiou, Daley, Thompson and Sonuga-Barke40 Mothers with ADHD tend to monitor their children with ADHD less, are less consistent in their parenting,Reference Murray and Johnson39 and show less ‘positive and involved’ parenting styles.Reference Psychogiou, Daley, Thompson and Sonuga-Barke40 There is some evidence, though, that ‘high levels of ADHD symptoms in mothers [ameliorate] the negative effects of child ADHD on parenting’, perhaps from having more ‘empathy or tolerance’ towards their child.Reference Psychogiou, Daley, Thompson and Sonuga-Barke40 However, it has been suggested that this empathy and tolerance might disguise a parenting style that lacks ‘consistent discipline’ and ‘clear boundaries’.Reference Psychogiou, Daley, Thompson and Sonuga-Barke40 Conversely, impulsive fathers may argue more with their children who have ADHD,Reference Harvey, Danforth, McKee, Ulaszek and Friedman38 and high levels of ADHD symptoms tend to have a more ‘negative’ effect on their parenting of children with serious ADHD.Reference Psychogiou, Daley, Thompson and Sonuga-Barke40 This could relate, as Psychogiou et al suggest,Reference Psychogiou, Daley, Thompson and Sonuga-Barke40 to fathers feeling ‘annoyed and/or overwhelmed’ by the combination of their children's ADHD and their own. Most children whose parents have ADHD are well cared for. However, a combination of the functional impairments of the disorder, as well as the commonly associated social impairments are considered by Mulsow et al Reference Mulsow, O'Neal and Murry41 to be potential risk factors for child maltreatment.

How can we help protect children and support parents?

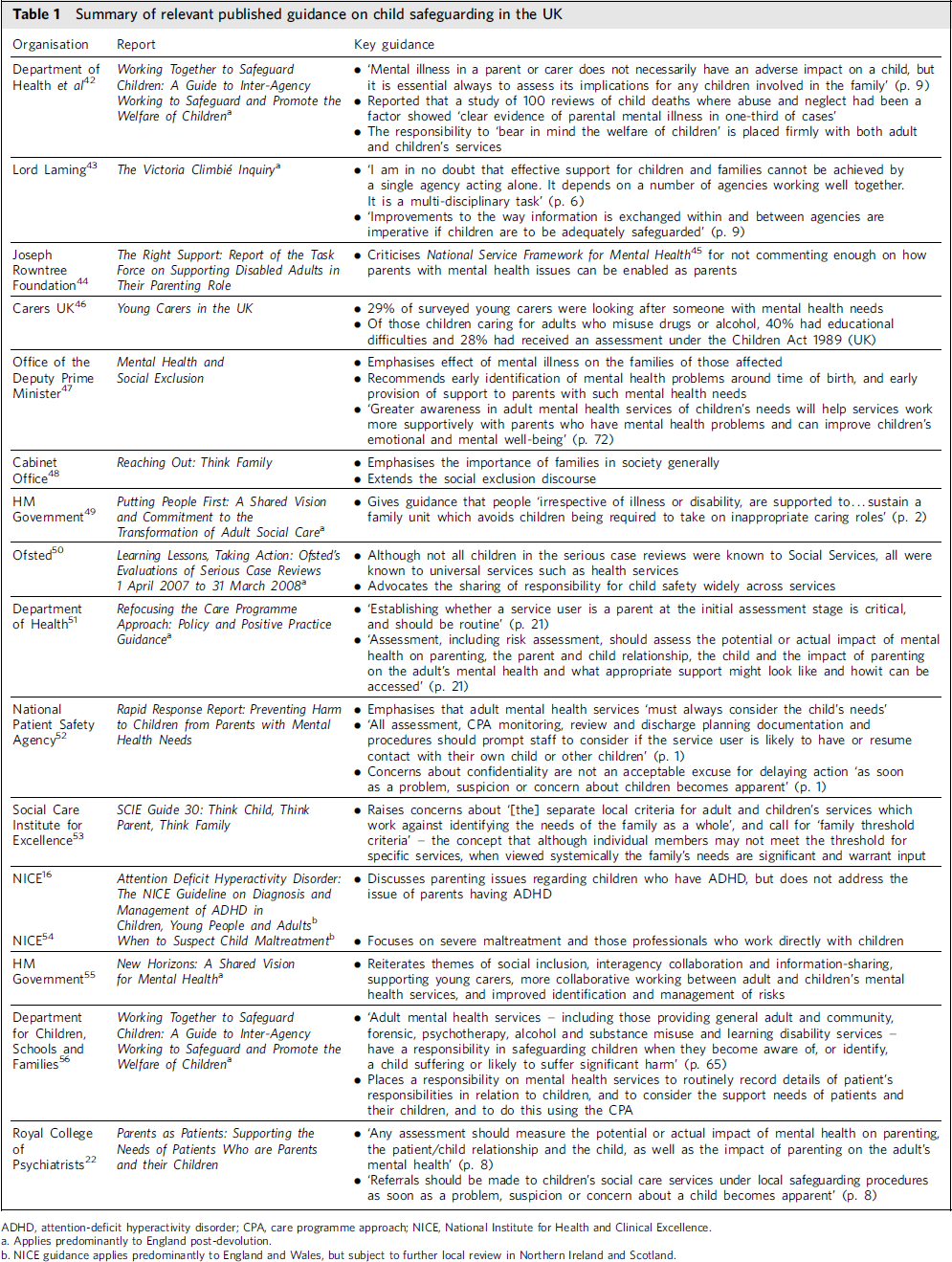

Table 1 attempts to collate and summarise a number of important reports from UK governmental and non-governmental agencies, relevant to child welfare, which may not be widely known to adult psychiatry services. The Royal College of Psychiatrists’ report Patients as Parents,21 and its successor Parents as Patients,22 highlight the responsibilities of mental health staff in safeguarding children. Although both reports emphasise that most parents with mental illness do not abuse their children, a high importance is placed on staff being aware of the needs of children, proactively considering their safety, and understanding the correct procedures to follow when concerns arise. This theme of asking adult mental health services to accept their responsibilities in this area is repeated in a number of other reports. Professionals working with adults are instructed to assess and document the parental responsibilities and key child safeguarding risk factors in relation to their patients. In addition, they are asked to share information with other agencies, acting appropriately and efficiently to ensure children are protected when safeguarding issues are suspected.

TABLE 1 Summary of relevant published guidance on child safeguarding in the UK

Identification and treatment of adult ADHD

Unlike many of the risk factors for neglectful parenting, ADHD symptoms are, as recognised by NICE,16 amenable to effective treatment with medication as part of a multidisciplinary holistic care package. There is some evidence that treating ADHD in adults might improve their parenting.Reference Evans, Vallano and Pelham56 In one study, methylphenidate treatment of ADHD in mothers whose children had ADHD was shown to improve consistency of discipline and reduce the use of corporal punishment on maternal self-report.Reference Chronis-Tuscano, Seymour, Stein, Jones, Jiles and Rooney57 Following randomised discontinuation of methylphenidate there was a non-significant deterioration in maternal involvement and poor monitoring/supervision in the group randomly switched to placebo. However, the sample size was small and the outcomes difficult to reliably measure, and therefore further research is needed to rigorously demonstrate the effects of treating adult ADHD on parenting capacity.

Remembering comorbidity

Comorbidity in ADHD is common and relevant to both child safeguarding and overall prognosis. It is therefore important to screen for other mental disorders in patients with ADHD. Because of their relevance to child safety, forensic and substance misuse histories should be routine and detailed. Given the wide variation in the presentation of adults with ADHD, assessment should be made of the effect of ADHD symptoms and comorbid symptomatology on each individual patient's parenting skills.

Improving service provision

At age 18 many patients treated for ADHD throughout adolescence do not receive an ongoing local service, due to a lack of clarity in commissioning and a shortage of experienced clinicians in adult services. This occurs just at the time they are entering independent adult life, with all the demands that that places on them to gain employment and form relationships. Investment into either local specialist ADHD services or the training of general adult psychiatrists to feel competent in diagnosing and managing ADHD is required to address this unmet need. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder is frequently perceived as outside the responsibility of adult psychiatry services. However, it is a very common treatable disorder, and the impairment from it can be substantial. We would suggest that knowledge and experience of ADHD should be a core skill for adult psychiatrists.

Should child psychiatry/paediatric services screen parents?

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder is the epitome of a psychiatric condition with high heritability. Professionals working with patients with ADHD often identify signs of the disorder in their patients’ relatives. Adults commonly present for help after they have had experience of a young relative with the condition. The question remains whether child psychiatrists and paediatricians should offer screening questionnaires to parents and whether they should be able to consider direct referral to local adult services.

Collaborative working

Collaborative inter-agency working is one of the key focus areas of Crossing Bridges,Reference Mayes, Diggins and Falkov1 an influential and oft-quoted manual to teach staff in adult mental health services how to address child welfare issues. Collaboration between disciplines within an organisation as well as between agencies is essential and should include Social Services, health services and family law professionals.Reference Xenitidis, Jeffs, Cubbin, Hon Lord Justice Thorpe and Faggionato58

Greater liaison between child and adult services when treating the same family, and more information-sharing, would be likely to protect children better. Additionally, knowledge of the impairments and treatment of one family member can be helpful to professionals working with their relatives. Adult psychiatrists have little experience in improving parenting skills in their clients and may learn much from a closer working relationship with children's services. Adult psychiatry has a responsibility to share concerns regarding child safeguarding with appropriate agencies. This is supported by the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA), who clarified that concerns about confidentiality are not an excuse for delaying action where there are fears that a child may be at risk.52 The Royal College of Psychiatrists reminds us that ‘children's rights to be safeguarded are paramount, even when they are perceived as interfering with the therapeutic relationship’ (p. 8).22

Multidisciplinary working is vital in delivering holistic care for families with ADHD where there are parenting concerns. This may involve psychiatrists, social workers, housing workers, employment professionals and others, but one professional must be identified to take the lead in coordinating the care package. Access to parenting programmes should also be made available.

Risk assessment

Parents as Patients states that ‘All psychiatrists and members of multidisciplinary teams should be familiar with legal and policy frameworks in their jurisdiction in relation to safeguarding children’ (p. 8).22 Establishing whether the service user ‘is likely to have or resume contact with their own child or other children’ (p. 8)22 is important, and professionals should be prompted to consider this in all formal documentation processes, including assessments and care programme approach reviews. This is supported by the NPSA and other organisations (Table 1), which strongly recommend that professionals record the full details of any children in close contact with adult patients, and assess the ‘potential or actual impact of mental health on parenting, the parent/child relationship and the child, as well as the impact of parenting on the adult's mental health’ (p. 8).22 Care programme approach and other local documentation forms should encourage professionals to do this.52

Although Parents as Patients particularly highlights parents with personality disorders, substance use disorders and intellectual disability, it also specifically mentions ADHD. The original Patients as Parents report21 discussed ‘the serious risks posed to children by parents with impulsivity, high levels of aggression and unstable relationships’ (p. 27). We suggest that recognition of ADHD in parents should prompt a careful risk assessment, with a particular focus on comorbid personality disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders, substance misuse and forensic problems.

Concluding comments

Most parents with ADHD are devoted to their children and able to look after them very well. For some adults, ADHD may have a positive impact on their parenting style, for example in terms of ‘enthusiasm, boundless energy, and playfulness’.Reference Weiss, Hechtman and Weiss31 The aim of our article is to make patients feel confident and competent in their parental role, through identifying their needs and signposting them to appropriate support. Even where there are parenting problems, these will often lead to relatively mild disadvantages. However, professionals working with parents who have ADHD need to remain alert to the small number of children who could be at significant risk. Further research is needed into the impact of specific symptoms on parental capacity and to investigate the efficacy of treatment strategies in improving the parenting skills of adults with ADHD.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.