Introduction

Do governments ‘punish’ interest organizationsFootnote 1 that are confrontational with institutions by withholding them from public funding? Scholars studying sources of income of civil society organizations claim that, yes, donors prioritize moderate organizations, who do not critically engage with funders. This is particularly relevant for, firstly, private foundations who allocate resources to moderate organizations in order to ‘prevent or reduce radical mobilization’ (Haines, Reference Haines1984). Secondly, it has been argued that the same logic applies to governments as public donors. According to the ‘paradigm of conflict’ thesis (Salamon, Reference Salamon and Salamon2002), governments, on the one hand, are reluctant to fund interest organizations if the latter are confrontational towards its institutions. On the other hand, confrontational organizations are reluctant to receive public funding, fearing that subsidies – tied to specific criteria – will threaten organizational autonomy (Chaves et al., Reference Chaves, Stephens and Galaskiewicz2004).

These expectations are based on the empirical observation collected in interviews with Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) leaders, who have indicated to be reluctant to ‘bite the hand that feeds them’ (Bass et al., Reference Bass, Arons, Kay and Carter2007; Onyx et al., Reference Onyx, Dalton, Melville, Casey and Banks2008) and are even fearful that future funding might be compromised if a critical stance towards government is taken (Chaves et al., Reference Chaves, Stephens and Galaskiewicz2004; Mosley, Reference Mosley2012). The key question we ask is whether this fear is justified. Are interest organizations that are confrontational in their advocacy activity towards government institutions indeed less successful in obtaining public funds than groups which are less critical or even cooperative with the government that funds them? Research conducted so far collects perceptions and experiences of funded organizations with public donors, with an exclusive focus on NGOs (neglecting other funded group types). Surprisingly, however, there is no research which explores the causal mechanism which links group attitudes towards the state to the obtainment of public funds. We argue that this is a relevant question, given that resource dependency theory (Chaves et al., Reference Chaves, Stephens and Galaskiewicz2004; Brown and Troutt, Reference Brown and Troutt2004; Onyx et al., Reference Onyx, Dalton, Melville, Casey and Banks2008; Mosley, Reference Mosley2012; Bloodgood and Tremblay-Boire, Reference Bloodgood and Tremblay-Boire2017), on which this study is built, assumes that such a link exists, without however exploring it empirically and quantitatively.

In this paper we therefore, for the first time, test whether more confrontational interest organizations are less successful in grant applications than cooperative ones. We hereby propose three (competing) hypotheses. First, in light of the concerns vocalized by NGO leaders about the effect of interest organization attitudes, we hypothesize that obtaining public funding is indeed less likely for groups which have a more critical advocacy attitude towards government institutions. Second, as an alternative hypothesis, we test whether there is no relationship between the positions interest organizations take and their success in grant applications. Third, we consider whether the association between attitudes and grant success applies to some groups only, such as NGOs, which are more likely to suffer from resource dependency as opposed to other organizational types (Hanegraaff et al., Reference Hanegraaff, Beyers and De Bruycker2016).

We test these hypotheses in the European Union (EU), where the donor is the European Commission (EC), and the funding applicants are politically active interest organizations at the EU level. The EU is the largest donor of interest organizations in the world, which makes it an ideal case for the study of the determinants and the effects of funding on interest organizational behaviour (Mahoney and Beckstrand, Reference Mahoney and Beckstrand2011; Bloodgood and Tremblay-Boire, Reference Bloodgood and Tremblay-Boire2017; Persson and Edholm, Reference Persson and Edholm2018; Crepaz and Hanegraaff, Reference Crepaz and Hanegraaff2020; Crepaz et al., Reference Crepaz, Hanegraaff and Salgado2021). Yet, so far there has been limited research on this issue in the EU (but see Sanchez-Salgado, Reference Sanchez-Salgado2014; Bloodgood and Tremblay-Boire, Reference Bloodgood and Tremblay-Boire2017), as most of the work relates to public subsidies in North America (Chaves et al., Reference Chaves, Stephens and Galaskiewicz2004; Brown and Troutt, Reference Brown and Troutt2004; Onyx et al., Reference Onyx, Dalton, Melville, Casey and Banks2008; Suárez, Reference Suárez2011; Mosley, Reference Mosley2012).

To tap into this gap, we conducted an extensive survey among a random sample of interest organizations listed in the EU Transparency Register (N = 458). We asked the leaders of these organizations whether they applied for funding between 2015 and 2018, and if so, whether their (at the time) most recent application was successful or not. Our analysis relies on both quantitative and qualitative evidence. First, we provide interpretative data provided by the respondents in open ended questions on the link between the success in grant applications and the attitude organizations have towards European Union institutions. Then, we complement this analysis with multiple regressions where we explain success rates in grant applications through attitudes towards the EU. Combined, our analysis allows us to empirically link attitudes to grant application success in the EU.

Our paper contributes to several debates. First, we directly contribute to the literature on civil society organizations’ resource dependency from funds. While there is an abundance of literature focussing on the response of groups to the potential to be excluded from funding (Chaves et al., Reference Chaves, Stephens and Galaskiewicz2004; Bass et al., Reference Bass, Arons, Kay and Carter2007; Onyx et al., Reference Onyx, Dalton, Melville, Casey and Banks2008), in purveying the literature we did not find any study systematically analysing to which extent this fear is empirically justified. Second, we contribute to the literature on interest organizations. This literature focuses mostly on ways in which interest organizations seek to influence government decisions (Bouwen, Reference Bouwen2004; Dür et al., Reference Dür, Bernhagen and Marshall2015; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Kai Mäder and Reher2018) but pays less attention to the reverse effect: how governments try to control interest organizations. While public funding is recognized, in the government’s toolbox, as a tool to mould civil society (Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2004), little is known about the extent to which state-interest organizational relationships matter for the distribution of public funds. With our paper we aim to provide a first step into this direction, by exploring whether confrontational advocacy relationships undermine public funding.

In what follows, we first provide an overview of the literature regarding the effect of state subsidies for the activities of interest organizations. We hereby identify some important lacunas in the literature. Next, we provide a set of three hypotheses to fill these gaps. In the section thereafter we present our research design. In our empirical analysis we combine quantitative analyses with qualitative findings provided by our respondents. In the conclusion we summarize the main findings and provide avenues for future research.

State of the art: the effect of public funds on interest organizations’ political activities

Interest groups are critical intermediates between constituents and policymakers (Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Kai Mäder and Reher2018). They provide essential information to politicians and civil servants in between elections (Bouwen, Reference Bouwen2004), they support policymakers in public and political debates (Dür et al., Reference Dür, Bernhagen and Marshall2015), and they monitor political developments for citizens and businesses (Nownes, Reference Nownes2006). Yet, interest organizations are not neutral transmission belts (Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Kai Mäder and Reher2018). While some collectively organize to represent economic sectors and professions, other mobilize around specific causes, solidly grounded in beliefs and world views (Leech, Reference Leech2006).

The representation and transmission of interests into the black box of politics is not a neutral process either. Wealthy organizations, often representing business and economic interests, have an advantage as far as lobbying policymakers and advocacy is concerned, specifically, because it is easier for them to overcome collective action problems and survive as organizations (Berkhout et al., Reference Berkhout, Beyers, Braun, Hanegraaff and Lowery2018). As such, in the population of interest organizations, wealthier and business organizations tend to be overrepresented. To assure a more balanced community of interest organizations, and to support the emergence of a diverse civil society, governments provide subsides to interest organizations. Neopluralists described this as a government tool in the hands of the state to level the playing field for interest organizations (Lowery and Gray, Reference Lowery and Gray2004). Associative democracy scholars interpret this as a way by government to support representation of underrepresented segments of society, whose voices are threatened to remain unheard if organizations seeking to represent them are not financially supported (Cohen and Rogers, Reference Cohen and Rogers1995). Either way, the principle behind public funding of interest organizations is that not only the strongest may survive but also groups which find it more difficult to attract private funds (Mahoney and Beckstrand, Reference Mahoney and Beckstrand2011).

Countries vary in terms of how generous in their funding schemes are (Wang, Reference Wang2006). Most Western-European countries as well as the European Commission provide billions of Euros supporting various types of interest organizations (Keijzer and Spierings, Reference Keijzer and Spierings2011). While this is beneficial for many of the receiving organizations, as this guarantees maintenance of the organization’s activities and ultimately survival, it also generates a dependency of interest organizations from the state (Fraussen, Reference Fraussen2014; Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Fraussen and Beyers2018). Research shows that funded organizations – even in OECD countries – would not survive if funding was eliminated. Public funds are by far the largest source of income civil society organizations rely on (Wang, Reference Wang2006). This resource dependency from the state has been described as having negative effects on the organizations’ activities in at least two ways. First, once funding is obtained, an organization may decide to channel its activities into grant writing rather than constituency work or service provision, because this increases the chances of organizational survival (Mosley, Reference Mosley2012). Secondly, obtaining funding may reduce organizational autonomy, in a way that organizations, fearing to lose future funding, align with the positions and the agenda of the state rather than with those of their constituents (Brown and Troutt, Reference Brown and Troutt2004; Chaves et al., Reference Chaves, Stephens and Galaskiewicz2004). In other words, it may lead interest organizations to become less critical of government policy because of fear of repercussions.

Many interest organization leaders indeed indicate that they fear such repercussions. NGO leaders indicate to be reluctant to ‘bite the hand that feeds them’ (Bass et al., Reference Bass, Arons, Kay and Carter2007; Onyx et al., Reference Onyx, Dalton, Melville, Casey and Banks2008). Organizations without government funding fear that funding in the future may be compromised if they take on too critical stances towards the governments that support them (Anheier et al., Reference Anheier, Toepler and Wojciech Sokolowski1997; Chaves et al., Reference Chaves, Stephens and Galaskiewicz2004). Even if actual instances of retaliation are rarely reported, NGO staff have sometimes declared examples of punishment (Chaves et al., Reference Chaves, Stephens and Galaskiewicz2004). Hence, non-profits frequently remain reluctant to even ‘engage government directly lest they anger government officials and jeopardize their contracts’ (Smith, Reference Smith2003, 40).

The question is: is this a legitimate fear? Do governments use public funding to obstruct certain voices and empower others? The only answers we have to this question, thus far, stem from studies focussing on funding success in non-democratic states and studies related to NGO funding by private donors. In both instances, attitudes matter (a lot) for grant application success. First, in many autocratic or hybrid political systems, states build higher barriers for unwelcomed groups to make the obtainment of funding more difficult and even impossible (Dupuy et al., Reference Dupuy, Ron and Prakash2015). Elites in power in these systems ‘usually have a broad network of influence, which can effectively cut off domestic groups that are working against their interests’ and this includes access to domestic funding (Parks, Reference Parks2008, 219). This is why international donations are widespread. For the same reason, however, these can be perceived as acts of interference by foreign countries which need to be regulated and limited (Henderson, Reference Henderson2002). For example, Russian authorities require that NGOs report political activities and receipts of foreign money (Dupuy et al., Reference Dupuy, Ron and Prakash2016). As far as private donors are concerned, we know they are very selective of who gets funded and select projects and organizations which are in line with the donor’s agenda (Haines, Reference Haines1984).

With this in mind, we still do not know whether public donors in democratic systems have comparable approaches in funding organizations. While there are certainly episodes of governments introducing policies to constrain civil society organizations because of public criticism or partisan reasons (Leech, Reference Leech2006), the extent to which funding is used as a tool to discipline and moderate confrontational behaviour is far less clear.

Most of the existing research focussing on the study of the effects of funding on organizational behaviour notices that organizations that are heavily dependent on public funding tend to have a more ‘state-oriented behaviour’ (Anheier et al., Reference Anheier, Toepler and Wojciech Sokolowski1997; Brown and Troutt, Reference Brown and Troutt2004; Mosley, Reference Mosley2012). This is evident in studies which show how publicly funded organizations deviate from advocacy because of fear to put their access to future funding at risk (Bass et al., Reference Bass, Arons, Kay and Carter2007; Onyx et al., Reference Onyx, Dalton, Melville, Casey and Banks2008; Mosley, Reference Mosley2012). Sometimes, this is even explicitly expressed in regulation which caps the legal time spent on advocacy if public funding has been obtained (Leech, Reference Leech2006). However, the extent to which funding is allocated to organizations because of their moderate, rather than confrontational, behaviour remains an untested assumption.

In the next section we argue that there are three potential answers to this question.

Hypotheses: attitudes and grant application success

In this section we provide three hypotheses regarding the relationship between the attitude of organizations towards EU institutions and the success these organizations have in obtaining European Commission (EC) funding. We refrain from prioritizing one hypothesis over the other, because a) of the lack of prior studies to build on; and b) because we think each of the hypotheses are logically derived and may apply to our case. Rather, we opted to present them as competing hypotheses, which need empirical verification.

The first hypothesis states that attitudes matter in the obtainment of public funding. This relies on the assumption, based in resource dependence theory, that governments exercise control over civil society organizations by managing the organizations’ access to financial resources (Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2004). With this idea in mind, NGOs who rely on public funding for survival need to be responsive to financially powerful actors, otherwise they will cease to exist (Mosley, Reference Mosley2012; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2012). In return for financial aid, states expect from civil society organizations that they will deliver the essential services they have been tasked with, including the implementation of government policy (Anheier et al., Reference Anheier, Toepler and Wojciech Sokolowski1997; Brown and Troutt, Reference Brown and Troutt2004; Sanchez-Salgado, Reference Sanchez-Salgado2010; Neumayr et al., Reference Neumayr, Schneider and Meyer2015). From the government’s perspective, it is hence essential for the success of this process that state institutions do not engage with civil society organizations that are confrontational towards government policy, since this may cause disruption in the implementation of policy and service delivery. One of the ways in which states can exercise control over the above process is by denying funding to organizations that are critical and confrontational in their advocacy activities. In doing so, public donors guarantee that only those organizations that are in line with the policy agenda and its direction will be carrying out publicly funded projects and services.

If this view is correct, we should see that organizations which are more critical of the functioning of the EU are less successful in grant applications. The European Commission has previously stated that among the objectives of its grants programme, the development of a European civil society plays a key role (European Commission, 2001). The EC funds projects and organizations which support the promotion of a European identity and European integration (Mahoney and Beckstrand, Reference Mahoney and Beckstrand2011). Based on what has been discussed above, one would then expect that organizations that are critical of European institutions and its policies will be less likely to obtain funds. Hypothesis 1 therefore states that:

H1: The more confrontational attitude interest organizations have towards the EU, the lower their chance to obtain a grant.

The rival hypothesis states that there is no relationship between the attitude of interest organizations and the success in funding applications. There are three main arguments for why the attitude of organizations may not matter. First, it can be beneficial for policymakers if the interest organization population holds many different views. Policymakers need to know what constituents are thinking to make sure there is public support for policies proposed by its government. This mechanism is particularly important for EU institutions, which have been previously accused of democratic deficit (Follesdal and Hix, Reference Follesdal and Hix2006). In the absence of a strong mechanism of input legitimacy based on, for example, pan-EU elections and the direct election of the Commission’s presidency, EU institutions have tried to make up for the democratic deficit by supporting an active interest organization community capable of acting as a transmission belt between EU institutions and European voters (Greenwood, Reference Greenwood2017). If the EC was purposely funding only moderate interest organizations, this would bias the European interest organization system in a way that is not reflective and representative of European public opinion. For example, if Euroscepticism was widespread among European voters, but the EC funded only Euro-friendly interest organizations, in the long run, the democratic mechanism of interest representation would be biased. This may result in poor input but also a lack of output legitimacy. In other words, it may be that policymakers prefer to hear critical voices via interest organizations upfront, rather than dealing with the consequences at a later stage.

Second, even if policymakers intend to use subsidies to moderate the positions of interest organizations, this does not mean that they would succeed in doing so. On the one hand, the capacity of the EC, with its relatively small bureaucracy, to screen funded projects and interest organizations is limited (Sanchez-Salgado, Reference Sanchez-Salgado2014). On the other hand, interest organizations adapt to funding schemes and may ‘hide’ any controversial claims or objectives in order to maximize their chances of obtaining funds. As such, the capacity to locate who is critical and who is not may simply be too difficult to effectively implement. After all, research on lobbying access already suggests that confrontational advocacy does not necessarily inhibit interest organizations’ access to policymaking (Crepaz et al., Reference Crepaz, Hanegraaff and Salgado2021).Footnote 2 If policymakers struggle or simply do not filter out confrontational organizations from policymaking, why would they do so for the allocation of public funds? To illustrate this better, one should consider that the most important objective of the EC funding scheme is to fund organizations which would otherwise not survive. Research however shows that wealthier and more professionalized organizations still retrieve most of the funds (Crepaz and Hanegraaff, Reference Crepaz and Hanegraaff2020). Similarly, funding insiders, that is organizations whose grant applications have been successful, are more likely to be successful in new funding applications (Crepaz and Hanegraaff, Reference Crepaz and Hanegraaff2020). These findings show that the EC funding mechanism falls short of its objectives. And if the objective of promoting to level the playing field for interest organizations through the redistribution of resources is not met, it is plausible to assume that the objective of moderating positions (if that is one) will equally be missed.

A third and final reason relates to the high complexity of the EU’s governance structure (Sanchez-Salgado, Reference Sanchez-Salgado2014). The fact that political actors on the receiving end of advocacy and funding evaluation are not the same, may neutralize the potential negative or positive impact of collaborative and confrontational advocacy. This differs from, for example, local government institutions where funding allocation and policymaking structures may overlap and political actors would therefore have the capacity to discipline interest organizations through access to funding. At the EU level, however, with this separation in mind, it should not be feasible for the EC to use this tool to discipline interest organizations. Overall, this means that:

H2: There is no effect of the attitude towards the EU of interest organizations on their chance to obtain a grant.Footnote 3

Finally, it may also be that attitudes only matter for some types of organizations that request funding. The majority of the literature regarding the link between funding and interest organizational political activity focuses on NGOs. In line with a behavioural definition of interest organizations, we include a much broader focus, most importantly by including business associations and firms applying for EC grants as well (Baroni et al., Reference Baroni, Carroll, Chalmer, Luz Maria Muñoz and Rasmussen2014). We do not want our findings to be driven by one type of organization as we want to speak to the extant literature, which has a focus on NGOs only. We will therefore test the effect of organizational attitudes on grant application success for NGOs and business groups separately.

Moreover, and more importantly, there are also good theoretical reasons why NGOs may be ‘punished’ harder for voicing a more critical position compared to business groups. That is, NGOs may be more frequently associated to critical advocacy towards government. This relates to the fact that their existence is anchored to a cause or an ideology, that is, an objective which is more likely to, at some point, clash with government policy. Sanchez-Salgado (Reference Sanchez-Salgado2014, 349) argues in this regard that ‘[t]here are… many cases in which NGOs, such as the platform of social NGOs, have been very critical of the position of the Commission, using slogans such as “Mr Barroso, you killed the European dream!” (Armstrong, Reference Armstrong2010, 109). Moreover, certain NGOs have filed complaints against the Commission before the Court of Justice of the EU for a lack of transparency’. Policymakers may anticipate such attitudes and hold NGO funding applications to a different standard compared to business organizations. For instance, it may be that NGOs are screened more on their advocacy positions than business organizations and – consequently – are punished more often for all too radical positions vis-à-vis the European Union. We therefore also include a conditional hypothesis where only critical NGOs are less likely to receive public funding while this does not apply to business groups:

H3: The more confrontational attitudes NGOs have towards the EU, the lower their chance to obtain a grant. There is no effect of the attitude towards the EU of business groups on their chance to obtain a grant.

Research design

For our analysis we rely on an original survey among interest organizations listed in the Transparency Register (TR)Footnote 4 in two waves. It is a requirement for organizations wishing to lobby the EU to disclose having received EU grants. This dataset includes more than 12,500 organizations, with approximately 2,500 having declared EU funds. In addition, the remaining organizations have either not applied for funding or have applied but did obtain funding. We base our sampling on these three groups, which allows us to understand if groups applied for a grant, and whether they were successful or not. For both waves we drew a random sample of 750 organizations from the TR. In doing so, we oversample funded organizations by a 2 to 1 factor, since funded organizations account for only 20% of the total number of organizations in the TR (otherwise this may have left us with few funded organizations in our data). The organizations included in the sample vary substantially across types and origins of the interest organizations (we count Europeanized business associations, firms from the USA, German labour unions and research organizations from Belgium, to name a few). In total we sent out surveys to 1,500 organizations (750 wave 1; 750 wave 2). The response rates were 42.4% in 2016 and 21.2% in 2018.

For all organizations, contact details were gathered for the director of the organization or the officer responsible for public affairs and/or communication. The survey contains various questions related to EU grant applications (see online Appendix 6 for an overview of all questions in the survey). That is, we asked them whether they applied – and if so – were awarded a grant provided by the European Commission over the past year (for an extensive description of the EU funding system, see online Appendix 1 in supplemental material). In addition, we also asked several questions related to their advocacy efforts and a host of organizational characteristics. Importantly, to the second survey wave, in addition to the original questions that were asked during the first wave, we added open ended questions about the relationship between a group’s attitude towards EU institutions and funding. The combination of these sources allows us to provide a quantitative analysis complemented by interpretative data about the perceptions that link attitudes to grant obtainment. A summary of the variables employed in the analysis is found in the online Appendix 2.

We asked whether the organizations have applied for funding since the start of 2015. 270 respondents declared that their organization had applied for EU funds since 2015, while 188 declared not to have done so. Since our dependent variable relates to the success of the application, we focus on the former organizationsFootnote 5 and ask organizations about the success and failure of their applications (‘Was your organizations’ application for funding successful/unsuccessful?’). We find that 195 were successful (we code these as 1), while 75 were unsuccessful (we code these as 0). This serves as our dependent variable: the success of grant applications by EU interest organizations.

Our independent variable is the attitude organizations have in their advocacy towards the European Union. More specifically, as part of a larger battery of questions concerning advocacy at the EU level, we asked the organizational leaders and public affairs departments to evaluate, on a scale from 1 to 10, their attitude towards two EU institutions, the European Parliament and the European Commission, whereby 1 meant very cooperative and 10 meant highly confrontational. As the answers were highly correlated (r = 0.76; P = 0.00***), we provide one indicator summarizing the overall attitude of groups towards the EU.Footnote 6 We believe this captures self-reported attitudes in a fairly accurate way.Footnote 7 We do however acknowledge some limitations. Our measure does not allow us to capture the target of the cooperative or confrontational advocacy attitude. While a reported confrontational attitude may indicate a critical stance towards a specific policy, it may also reflect a broader opposition towards, for example, EU integration and or treaty ratification. Unfortunately, we cannot test for this detail in our data. However, our measure of attitudes captures a broad variation of confrontational attitudes and, as seen in the analysis, even most critical organizations get funding. We are therefore not concerned about our measure’s shortcoming. Nevertheless, we entrust future scholarship with the task of accounting for such relevant nuances.

To test H3, we construct an interaction between organizational type and attitude. In the survey we asked organizations to self-identify as business association, professional organization, NGOs or citizen group, labour union, research institute and firm. We combine these six categories into a simplified distinction between NGOs, business groups, and a rest category, in line with previous interest organizations literature (Dür et al., Reference Dür, Bernhagen and Marshall2015). The rest category includes professional associations, labour union, and research institutions.

In the analyses we control for a set of alternative explanations. First, we control for financial resources, which are shown to determine an organization’s ability to successfully obtain EU funding (Crepaz and Hanegraaff, Reference Crepaz and Hanegraaff2020). We asked respondents to indicate the budget of the organization in 10 categories ranging from ‘less than €100,000’ to ‘more than €1 bn’. For similar reasons, we control for the level of organizational complexity (Crepaz and Hanegraaff, Reference Crepaz and Hanegraaff2020). We included indicators of organizational complexity in our survey (specifically, if the responding organization had a board of directors, a secretariat, a financial department, a public affairs or communication department) and created an additive index ranging from 0 (meaning low organizational complexity) to 6 (meaning high organizational complexity). We also control for whether organizations applied as part of a consortium, because previous research has found a weak statistical correlation between consortium applications and success in obtaining a grant (Crepaz and Hanegraaff, Reference Crepaz and Hanegraaff2020). Third, to account for the previous success in grant applications we asked the surveyed organizations to evaluate the success rate of their applications during the past five years (ordinal scale of five categories). Past success rate is a strong predictor of application success, as both experience and track record matter in funding allocation (Suarez, Reference Suárez2011; Crepaz and Hanegraaff, Reference Crepaz and Hanegraaff2020). Fourth, we are controlling for the importance of the funding for each organization’s survival. For many organizations, the obtainment of funding from public donors is vital (Chaves et al., Reference Chaves, Stephens and Galaskiewicz2004; Sanchez-Salgado, Reference Sanchez-Salgado2014). Organizations that need funding should hence be more likely to put more effort and resources into the application process than interest organizations that do not count on external funding for the conduction of their activities. We therefore asked organization to ‘evaluate the importance of the grant for the sustainability of their organization’ and included the answers (ordinal from ‘not important at all’ to ‘extremely important’) in our analysis. Fifth, we control for the share of the application’s budget reserved for advocacy purposes. It may be that groups, which ask for resources to do lobby work, are more monitored for the type of attitude they have and that this might impact their likelihood of receiving a grant (Leech, Reference Leech2006). Sixth, another potential source of bias we control for relates to the Europeanization of interest organizations and their geographical origin (Mahoney and Beckstrand, Reference Mahoney and Beckstrand2011; Sanchez-Salgado, Reference Sanchez-Salgado2010). In general, ‘the Commission tends to reach out to European civil society and specifically to Euro groups’ (Mazey and Richardson, Reference Mazey, Richardson and Richardson2006, 228; Sanchez-Salgado, Reference Sanchez-Salgado2014, 345). Finally, organizations originating from EU − 15 member states are also more likely to obtain funding compared to member states of Eastern Europe (Mahoney and Beckstrand, Reference Mahoney and Beckstrand2011). This is because civil society might be ‘so weak in some countries that the organizations do not have the resources to even develop a proposal, or a proposal that is competitive enough against older, better-resourced, western-based organizations’ (Mahoney and Beckstrand, Reference Mahoney and Beckstrand2011, 1354). We asked organizations to indicate their country of origin and whether they have members/clients in multiple member states of the EU. Based on the answers, we constructed dichotomous variables for ‘Pan-European organizations’ and groups based in ‘EU − 15 member states’.

Results

We present two sets of data analysis. First, based on qualitative data from 60 interest organization leaders, we analyse the perceptions of these organizational representatives about the relationship between attitudes and success in obtaining EC grants. This establishes whether organizational leaders fear being punished for having a confrontational attitude. In the second part, we run a multivariate analysis based on the actual ability of 270 respondent organizations to acquire EU funding. This way we test whether more confrontational organizations are (indeed) statistically less likely to obtain funding from the European Commission compared to more cooperative organizations.

Qualitative illustration: do respondents fear repercussions for their confrontational attitude?

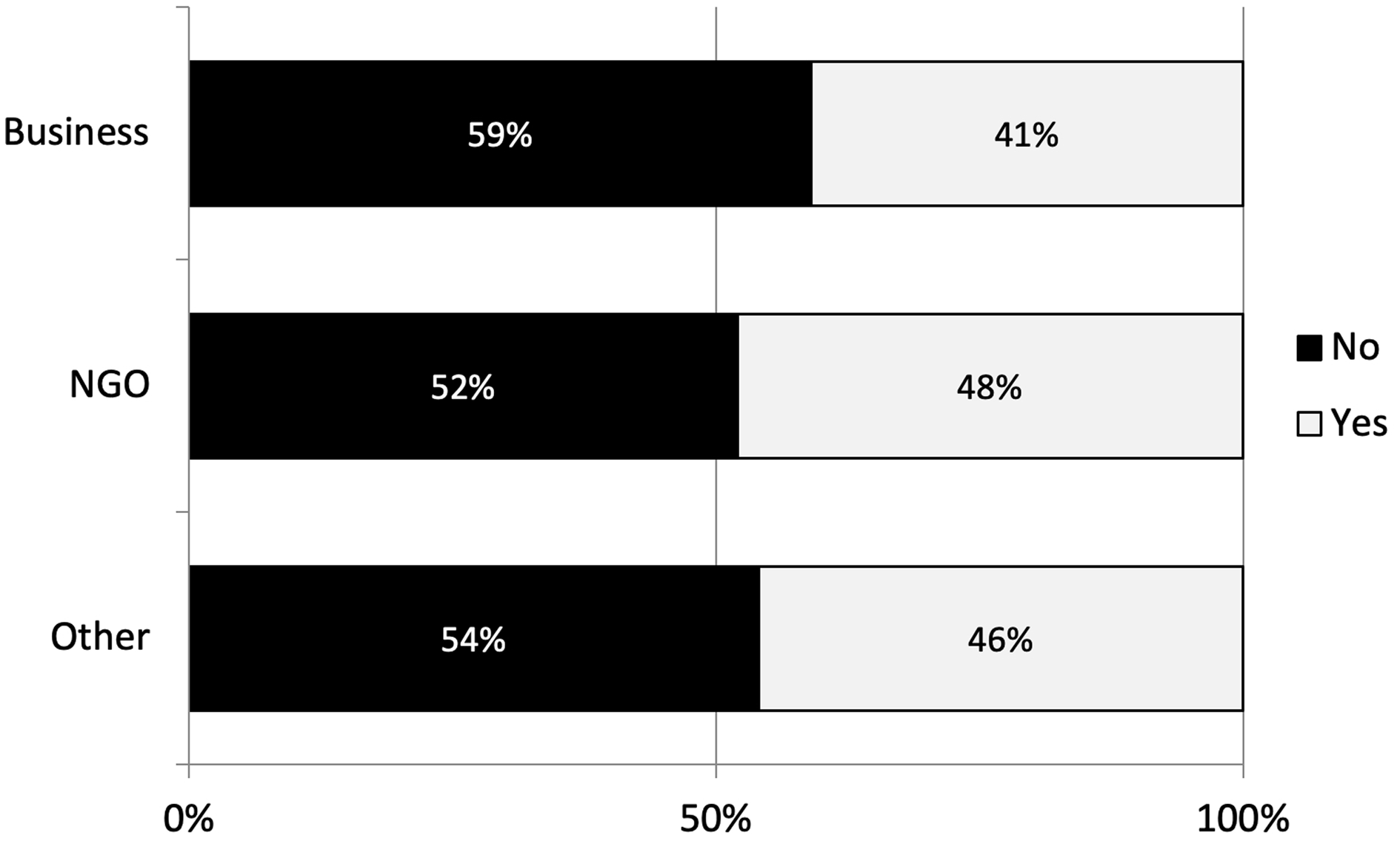

In the survey we asked participants whether they thought that a confrontational or cooperative advocacy attitude had a negative or positive effect on grant applications. In presenting the answers, we make a distinction between different organizational categories, namely NGOs, business organizations, and a residual category including labour, professional organizations and research institutes. As seen in Figure 1, almost half of the NGOs, just over 40 percent of the business groups, and 46 percent of the other organizations indicate that they believe that attitudes play a role in grant obtainment. This finding supports earlier accounts of studies where interest organization leaders express the same perspective (Anheier et al., Reference Anheier, Toepler and Wojciech Sokolowski1997; Chaves et al., Reference Chaves, Stephens and Galaskiewicz2004; Bass et al., Reference Bass, Arons, Kay and Carter2007; Onyx et al., Reference Onyx, Dalton, Melville, Casey and Banks2008). While most of these studies stem from the North American context, these results show that this is also a common perception among organizational leaders operating at the EU level.

Figure 1. Do organisations think that attitude towards EU institutions affects success in grant application, by different types of groups (Business, NGO, Other)

Note: based on question in survey: “Do you think the attitude of your organization towards the European Union affects the success rate of your applications for funding?”

To collect further evidence, we integrated the above question with an open question on why they think attitudes matter for grant applications. Some organizations stated that the conformation with EU objectives is part of the application procedure. For instance, one respondent indicated that ‘participation in EU funded projects by definition requires having a positive, pro-European attitude and complying with EU values and objectives. Moreover, our organization’s objectives are aligned with EU objectives, and this is also reflected in every project we submit to the EU for funding’. A second one stated that ‘the level of engagement towards the achievement of EU policy objectives is an important factor’. A third respondent stated that ‘if you are in line with their ideas [refers to EU bodies] you have more chances to get the grants awarded’. In a final example, one respondent stated that ‘feeling positively about the EU makes the task [refers to application process] easier’.

In total, 46 percent of the respondents indicated that attitudes matter. These statements align with more quantitative evidence suggesting that the alignment with EU objectives is perceived as one of the ‘top three reasons’ for application success for 52 percent of the funded organizations we surveyed. However, it might well be that these organizations believe attitudes to matter, without having based this perception on any empirical observation, that is, actual retaliation. This is because they themselves have a cooperative attitude towards the EU. In fact, 74 percent of the surveyed organizations declare to have very cooperative to fairly cooperative attitudes towards EU institutions. In these instances, organizational leaders indicate that the organizational objectives are closely aligned to EU objectives. Yet, they do indicate that if this was not the case, it would dampen their success rate. For instance, a respondent of an interest organization which has successfully applied for EU funding and declares overall cooperative attitudes towards EU institutions indicates: ‘Only in aligned objectives where we differ from EU views applications could be harder – we align strongly however so little conflict in aims’. This statement aligns with the findings in Chaves et al. (Reference Chaves, Stephens and Galaskiewicz2004) who report that groups anticipate a rejection by not asking for funds in areas where they believe confrontation would be a disadvantage.

However, not all organizations participating in our survey agree that their attitude matters for application success. As shown in Figure 1, the majority of our respondents still perceived attitudes as ‘entirely unrelated’ to grant application success. Most frequently, respondents express that EU officials are professional and transparent, that the expert evaluation process is independent and ‘does not factor attitude’ into the decision-making procedures. For instance, one respondent strongly stated that only professional characteristics are used in the evaluation criteria: ‘We believe that the assessment of proposals has nothing to do with the organizations’ attitude. It is the feasibility, potential, and benefits of the project that are being judged by the EU’s experts’. Another argument for why attitude does not matter relates to the division of labour in the European Union. As much lobbying in the EU is inside lobbying (Dür et al., Reference Dür, Bernhagen and Marshall2015), any confrontational attitude of an interest organization in advocacy would only be noticed by policymakers working in the Commission or the Parliament (as these are the target audience of most lobbyist). These, however, are not the people evaluating interest organizational proposals for funding. As discussed in relation to H2, in the EU ‘the debates with the members of Parliament and Commission staff have no direct link with experts evaluating the project proposals’.

Finally, it is also not the case that only groups, which are cooperative to begin with, think that attitude does not matter for grant application success. Also, several interest organizations which have displayed a critical stance towards the EU indicate that it did not matter for a successful grant application. These quotes nicely illustrate this point. Firstly, ‘I haven‘t seen any sign that our sometimes very strong advocacy would change the attitude [towards us]’, and secondly ‘why should it be the case [that attitudes determine application success]? We are critical enough, but eager to seek for compromise’.

Overall, the evidence is split. These illustrations provide both strong arguments in support and against the expectations that a link between attitudes and grant application success exists. At first glance, the results resemble earlier studies regarding the fear of organization leaders that attitudes matter. Almost half of the respondents indicated that attitudes matter. Moreover, it seems that NGO leaders are slightly more worried than leaders of other organizations (Figure 1). These are, however, only perceptions expressed by organization leaders. The question is whether these fears empirically translate into statistically different success rates for confrontational and cooperative organizations. We turn to this next.

Multivariate analysis: the effect of attitudes on grant application success

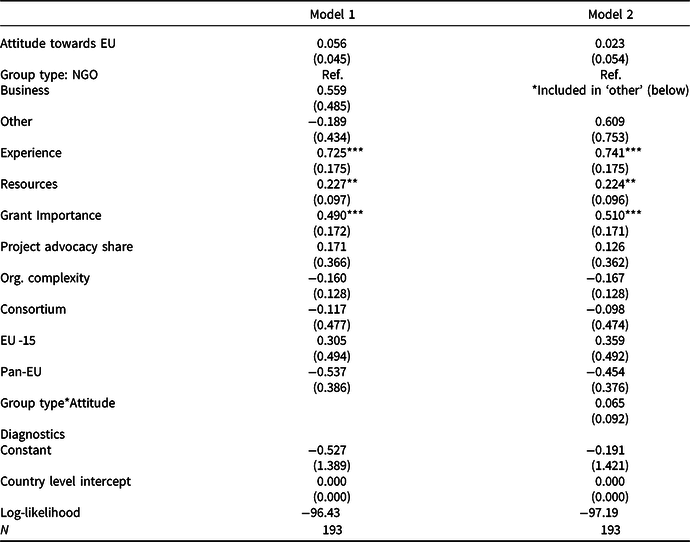

The multivariate analysis focuses on grant applications and whether groups successfully obtained the requested grant. The dependent variable in this analysis is a dichotomous variable, indicating success in gaining a grant (=1) and having no success in gaining a grant (=0). In total 195 of the respondents received a grant, whereas 75 did not. To account for the nature of our data we rely on logit regressions. Moreover, the data is hierarchical, with funding clustered by countries/EU. To account for this, the logit regressions were conducted with random intercepts for the countries/EU from which the interest organizations originate, using mixed-effects estimation models. Our key independent variables are an organization’s ‘attitude’ towards the EU and its organizational type (being either NGO, business organization, or ‘other’). We control for past success with funding applications, the financial resources of an organization, the importance of the grant for an organization’s survival, the share of the requested grant geared towards advocacy purposes, the level of organizational complexity, whether the organization applied as part of a consortium, whether the organization stems from an EU − 15 country, and, finally, whether the organization is an EU-level organization (as opposed to nationally based). The results are presented in Table 1. Both model specifications pass post-estimation goodness of fit using Hosmer-Lemeshow tests and we do not find evidence of specification error.

Table 1 Logit regression of the likelihood of receiving grants or not (N = 193)

Notes: The model is a mixed-effects logit regression which estimates a random intercept for all 26 countries/EU. The dichotomous dependent variable represents whether an organization obtained a grant or not. Coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. Levels of significance are presented, whereby: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

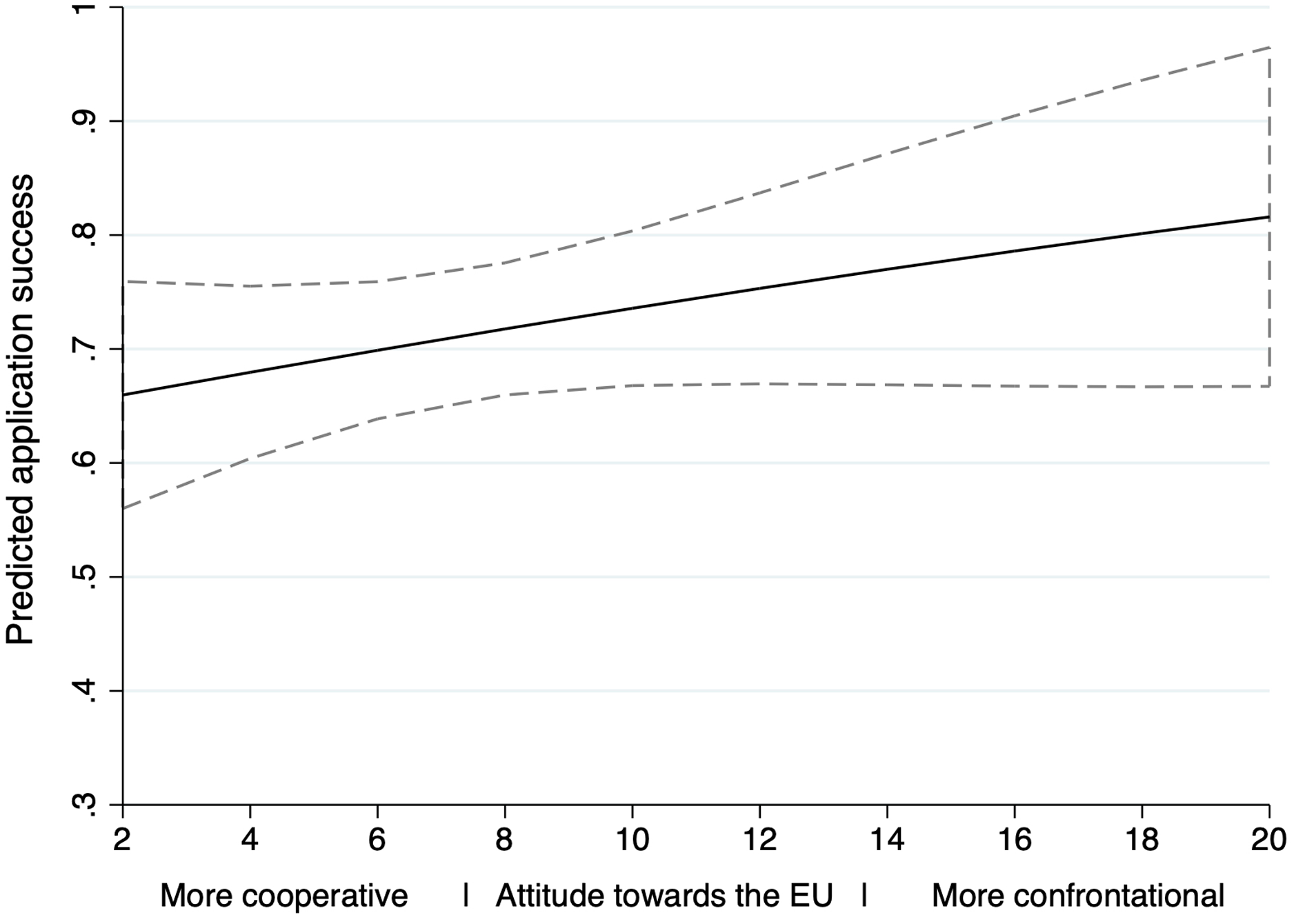

What are the main findings? As can be seen in Table 1, there is no consistent statistically significant relationship between the attitudes of interest organizations towards the EU and their chances of obtaining a grant. To highlight the exact nature of the relationship, we plotted the predicted probability of an interest organization to obtain an EC grant, for different levels of attitude. As discussed, attitudes range from 2–20, whereby a high score means that groups indicate more confrontational attitudes towards EU institutions. A low score means organizations indicated that they have a very cooperative stance towards the EU and its policies. In Figure 2, the results are presented (based on Model 1, of Table 1).

Figure 2. Predicted chance of application success by attitude

Note: based on model 1, Table 2. Confidence interval at <0.05. Application Success is dependent variable.

Two things stand out when observing the predicted trend in grant application success. First, the relationship is clearly weak, as indicated by the rather flat curve. Secondly, the relationship is not significant as can be seen by the confidence intervals overlapping almost entirely. This indicates that there is no relationship, even when we compare the most cooperative organizations (left end of the figure) with the most confrontational organizations (right end of the figure). Second, the slight increasing slope we do observe follows the opposite direction than expected. That is, while not significant, the more confrontational groups in our sample were slightly more successful in grant applications (not less). Again, this is not significant, so we cannot extrapolate these findings to the population, but it does highlight that there is no effect of attitudes on grant application success. We therefore reject hypothesis 1, which indicated that there is a relationship between interest organizations’ attitudes and grant application success. Rather, we accept hypothesis 2, that there is no relationship between the attitudes of organizations and the grant application success they have.

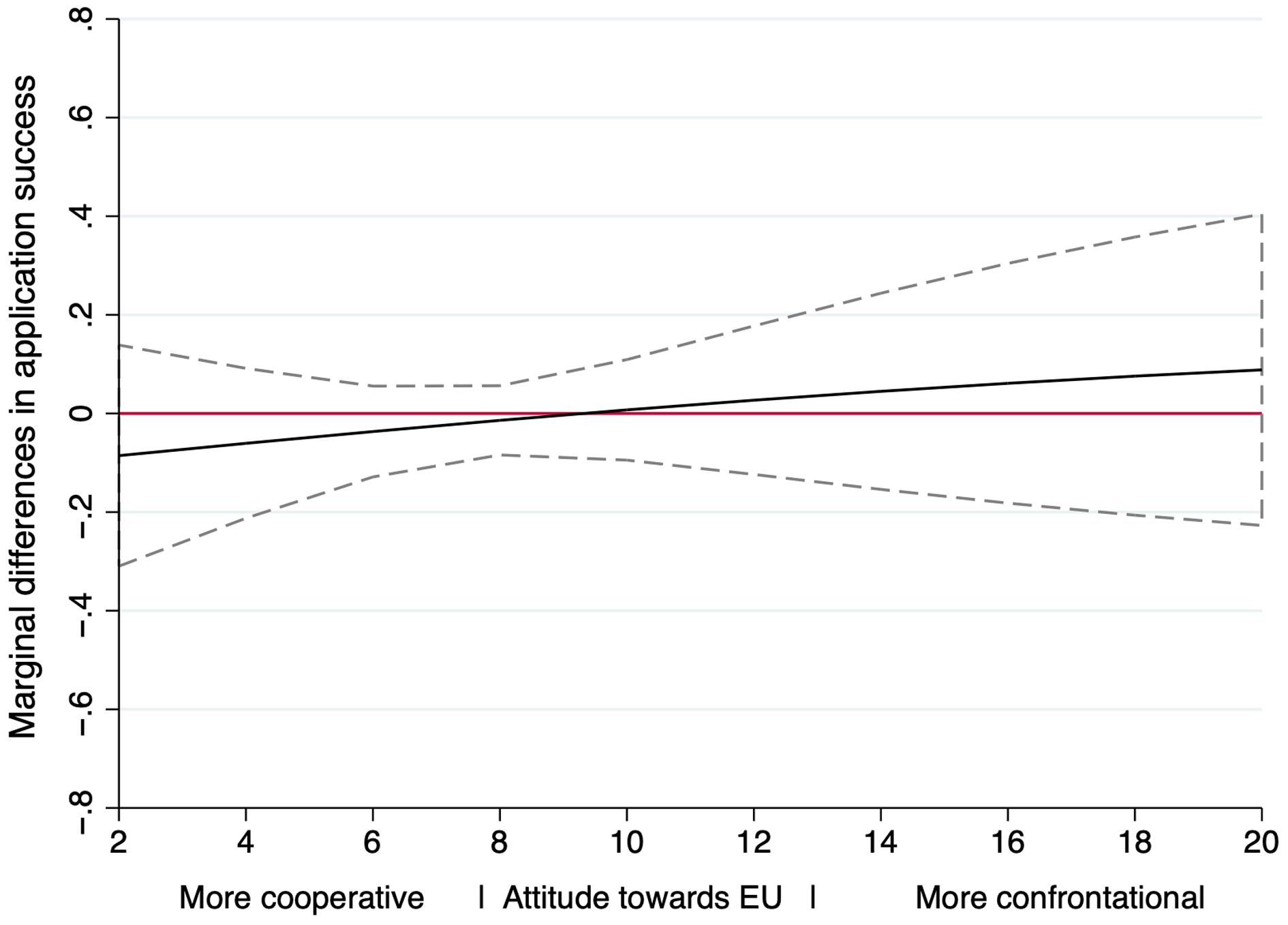

We however hypothesized that the effect of attitudes on the success rate of grant applications may only apply to NGOs, not other types of organizations, because of their higher tendency to depend on public funding for survival and their likelier engagement in confrontational advocacy. To test this hypothesis, we added an interaction between attitude and group type: being an NGO versus other organizational types. In Model 2 (Table 1) the results are presented. The interaction is not significant, yet it may still be that there are significant differences across different levels in an organization’s attitude. We plotted the marginal differences in grant success, among NGOs and other types of interest organizations at various attitude levels. The results are presented in Figure 3. The figure highlights whether there are any significant differences between NGOs (red base line) and other group types (black line). As clearly seen, it does not matter whether applicants for EC grants are NGOs or not, all have an equal chance to successfully obtain funding, most importantly, at all attitude levels. In other words, very confrontational and very cooperative NGOs have equal chances to see their application granted (as do other types of organizations). This rejects hypothesis 3: NGOs do not face any punishment for being more critical of the EU and its policy in relation to their funding applications.

Figure 3. Marginal difference in application success, by attitude * NGO vs others

Note: based on model 2, Table 2. Confidence interval at <0.05. Application Success is dependent variable.

Robustness checks: excluding bias and alternative explanations

To make sure our results are robust, we ran a variety of additional analyses, including some tests which focus on alternative explanations. First, one important caveat of our analysis may be that more critical organizations decide not to apply at all, to anticipate and avoid rejection. As indicated in the descriptive analysis, at least a few organizations indicated this to be the case. The question is whether this is a generalizable trend or whether these are outlier cases. If it is part of a trend, there may still be an effect of the attitude of organizations for grant success, yet in a more indirect manner: that is, by not applying at all. To account for this plausible mechanism, we conducted a regression analysis where the dependent variable is whether an organization indicated to have applied for a grant between 2015 and 2018 or not (N = 458) regardless of whether such application was successful or not. Our dependent variable therefore equals to ‘one’ if the organization applied for funding between 2015 and 2018 and ‘zero’ if it did not. Our explanatory variable is, again, attitude. This way we can observe whether most confrontational organizations opted out from the application process. To ensure robust results, we control for group type, financial resources of an organization, organizational complexity, whether an organization stems from an EU − 15 country, and whether it is a pan-European organization. As the dependent variable is dichotomous, we rely again on logit regression. We also include random intercepts for the countries/EU from which the decision-makers originate, using mixed-effects estimation models. The results are presented in online Appendix 4. The results indicate no statistically significant relationship between attitudes of interest organizations towards the EU and their willingness to apply for EC funding. Regardless of whether or not groups have a critical or cooperative attitude towards the EU, they are both equally likely to apply for funding (while controlling for relevant alternative explanations). We therefore rule out the possibility that our main findings are biased by not accounting for organizations that did not apply for EC grants.

Second, we also checked whether NGOs refrained from applying for funds if they are more confrontational. To this end, we added an interaction effect between attitude and group type. As can be seen in Appendix 4, Model 2, there is no significant relationship between this interaction and the propensity to apply for a grant. We show marginal differences for Model 2 between NGOs and other types of organizations in Figure A4, which suggests that there is no difference between the group types. Only when organizations are very cooperative (values between 2 and 6), then NGOs have a slightly higher chance to apply for an EC grant (see dotted line) compared to other types of groups with a cooperative attitude (red base line). Yet, for more confrontational groups (14 to 20) there is no difference at all between NGOs and other types of organizations. Moreover, there is no difference among confrontational and cooperative NGOs in applying for a grant. Combined, this means that there is no systematic self-selection among NGOs which are critical of the EU in that they do not ask the EU for funding compared to other types of groups and compared to more cooperative NGOs.

A final caveat concerns the importance of the grant for an organization’s survival. It might be that we find no association between attitudes and grant success because groups align with EU objectives, despite their attitudes, as they desperately need the funding. As a result, the study of attitudes alone may not tell us the entire story, if ‘how groups adapt’ to specific calls for funding is not considered. We assume that groups that need the funding for organizational survival will adapt to EU goals. Hence, if resource dependency theory was true, we would expect to find no association between attitudes and grant success, when the obtainment of the grant is perceived as extremely or very important for the survival of the organization. On the contrary, this association should be negative and significant, when the obtainment of the grant is not perceived as crucial, since organizations – in the absence of dependency from funds – can be ‘truthful’ in their behaviour. The results are presented in online Appendix 5. We find no evidence of this mechanism, meaning that the obtainment of EC grants for confrontational organizations does not seem to depend on whether or not they adapt to EU objectives based on their need for funding.

Conclusion

Based on our analysis of the determinants of EC grant applications success, it can be concluded that attitudes towards EU institutions do not seem to matter for the obtainment of funding. While many interest organization leaders believe that confrontation with political institutions is counterproductive and will result in retaliation and curtail of funding, we nevertheless show that on average applicants ‘can bite the hand that feeds them’ without fear of repercussions. We demonstrate this using both qualitative and quantitative evidence drawn from a representative survey we conducted between 2016 and 2018 with 270 organizations who applied for EC grants after 2015. First, in our qualitative illustration it was shown that there is the belief amongst 46 percent of the organizations participating in our study that positive attitudes towards the EU pay off for grant application success. Based on the regression analyses conducted, we show that this is likely a false perception. Much in line with the set of responses provided by the remaining 54 percent who did not perceive attitudes to matter for application success, the EU does not seem to evaluate grant applications based on the political positions of interest organizations. Our models show that this holds true across all types of organizations, even NGOs that were expected to suffer most from resource dependency. We consider our results to be robust as we account for self-selection bias into the application process and for the impact of the grants’ importance in terms of organizational survival.

Our findings challenge previous scholarly research, and even some of our own recorded qualitative findings, that report perceptions of fear of retaliation among organizations that are afraid of ‘biting the hands that feeds them’ by taking confrontational stances. This puts resource dependency theory into a new perspective highlighting that there is an incongruence between perception and observation, at least on average and as far as the EU is concerned. In doing so, our study contributes to much of the CSO literature that, in interviews with NGO leaders, finds evidence of fear of government response to critical advocacy. Finally, our analysis adds another piece to the study of EU interest organization relationships, with a perspective that considers public funding and an interest organization’s attitudes towards public institutions. We are tempted to infer from our results that the EU has an open and participatory approach to interest organizations, non-interventionist when it comes to determining the policy agenda of funded organizations. After all, it is the EC itself that declares the funds’ objective is that of balancing ‘the input of interest organizations and guarantee an open participatory political system for all interests [emphasis added]’ (European Commission, 2001: 1). Of course, we cannot conclude this with certainty from this study. More evidence and data on EU funds need to be collected to better understand the relationship between interest organizations and the political system. In particular, scholars are invited to take a donor-side perspective (in our case, the perspective of the European Commission) which pays more attention to factors related to government institutions, to their role and constraints as a public funder (Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2004).

In terms of avenues for future research, our study points, first, towards the need to fill the gap between observational and interpretative work. In the USA, where most of the interpretative work on resource dependency stems from, an investigation of the likelihood of grant application success based on attitudes towards state institutions becomes essential. A similar approach can be applied to test whether the fear of repercussions in the USA is perhaps more valid, although we expect no strong differences. This is mostly because the USA system is also based on a clear difference between the targets of lobby efforts and those evaluating grant applications. As discussed in this study, this association may prove different in other contexts, for example, in local government institutions, where structures of policymaking and grant allocation overlap.

Second, in our study we rely only on a self-reported assessment of attitudes. While we report that survey participants found it easy to position their organization’s attitude towards EU institutions and policies, complementing this self-reported data with coded observations and alternative measures of attitudes retrieved from newspapers and/or other forms of public communication would represent an improvement. By measuring attitudes in media sources, one could further validate our findings. This, more qualitative, approach would be especially helpful in understanding whether some attitudes or confrontational activities are ‘a bridge too far’ for the EU. For instance, it may well be that certain NGOs which seek a paradigm shift from EU integration are not funded. The EC may discipline these organizations to signal the boundaries of accepted critical engagement to other organizations. We cannot rule this out in our analysis and believe a deviant case study would be the most appropriate approach to investigate such research questions.

An additional path for future research, which we have not accounted for, is to analyse variation in grant success across policy fields. For instance, it may be that in policy fields where the core values of the European Union are at stake – such as in single market, human rights, or environmental issues – critical voices do get less funding. Again, this goes beyond the purpose of this paper and the level of detail in our data.

Our findings do however have clear normative consequences. First, our results highlight that leaders of interest organizations can voice their criticism of EU institutions, without any fear that this may limit their survival options. We believe this weakens the argument, put forward by some organizations, that EU funding should not be requested if a certain degree of independence is to be maintained. Our results suggest that one can remain autonomous, at least as far as advocacy attitudes are concerned, while receiving funds from the EC. We see this as a testament to the democratic values of the European Union, at least in terms of the system of EU funding. Vibrant debates can only flourish if actors are not restricted by dependencies to public institutions. The freedom to express unformattable positions to government institutions is among the pillars of democratic polities. Our results highlight that the EC does not only provide lip services when proclaiming this basic right, but actually puts money where their mouth is (or isn’t). While we realize that getting funded is not the same as being heard, at the very least EU funds make it possible for interest organizations to voice their opinion through advocacy without the fear of losing vital financial support. We hope this to be a sign of a broader attitude among EU policymakers to uphold democratic values in the European Union.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773922000145.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the three anonymous reviewers and the editors for their support and suggestions during the review process.