Introduction

This interdisciplinary study was based on both psychological and sociological approaches, mainly Merton's stress theory (Merton Reference Merton1938) and psychological theories on the effects of social media on wellbeing and social interaction, to shed light on social withdrawal.

Acute social withdrawal, which also includes the phenomenon of hikikomori, concerns adolescents and young adults who have withdrawn from society, retreating to their rooms for months or years and severing almost all ties with the outside world. Never described before the late 1970s, hikikomori has become a silent epidemic, with hundreds of thousands of cases now estimated in Japan (Saitō and Angles Reference Saitō and Angles2013). One observational study estimated that 1.2 per cent of a community in Japan (around 232,000 people) had experienced youth social withdrawal (Koyama et al., Reference Koyama, Miyake, Kawakami, Tsuchiya, Tachimori and Takeshima2010).

The large-scale use of the term in psychiatric literature can be traced back to the mid-1980s (Teo Reference Teo2010), after Japanese psychiatrist Tamaki Saitō's work (Reference Saitō1998) provoked a national debate about the causes and extent of the problem. According to Saitō and Angles (Reference Saitō and Angles2013), hikikomori were mainly male, middle-class young people who spent six months or more in an asocial state, and had experienced adverse childhood experiences such as bullying in junior high school.

Hikikomori has long been considered a ‘culture-bound’ syndrome (Sakamoto et al. Reference Sakamoto, Martin, Kumano, Kuboki and Al-Adawi2005; Cole Reference Cole2013) especially widespread in Japan (Teo Reference Teo2010), as a result of the troubled process of modernisation of the country after the Second World War. Socio-cultural factors related to the phenomenon are child-rearing practices characterised by an intense bond between mother and son, similar to a form of dependence (amae), alongside a poor relationship with an absent father; and religious factors, such as the Confucian perspective, based on harmony within the group, which discourages individual expression (Zielinziger Reference Zielinziger2006). Contemporary young people increasingly exposed through media to Western individualist values are less eager to conform to traditional social norms, and they are not always able to find a way to cope with these different pressures (Lassiter et al. Reference Lassiter, Norasakkunkit, Shuman and Toivonen2018).

In the last decade, an increasing number of cases have been reported in different countries around the world – in the Asian continent and the Arab region as well as in the United States (Kato et al. Reference Kato, Shinfuku, Sartorius and Kanba2011), and in the south of Europe; in Spain (Ovejero et al. Reference Ovejero, Caro-Cañizares, de León-Martínez and Baca-Garcia2014; Malagón-Amor et al. Reference Malagón-Amor, Córcoles-Martínez, Martín-López and Pérez-Solà2015), and recently in Italy (De et al. Reference De, Caredda, Delle, Salviati and Biondi2013; Ranieri et al. Reference Ranieri, Andreoli, Bellagamba, Franchi, Mancini, Pitti, Sfameni and Stoppielli2015). Different theories have been advanced to interpret the phenomenon: youth issues such as NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training; Furlong Reference Furlong2008) or a type of lifestyle (Chan and Lo Reference Chan and Lo2013). Not only psychological factors, such as maladaptive interdependence, associated with fear of criticism and rejection, and counterdependence, namely the refusal of attachment and dependence, but also socio-cultural factors must be taken into consideration to disentangle social withdrawal trajectories (Li, Liu and Wong Reference Li, Liu and Wong2018). The wide diffusion of this phenomenon also suggests a form of response to social and economic change that transcends culture, being an anomic and adaptive strategy to cope with the collapse of traditional structures of opportunity and the precariousness of youth transitions. The hikikomori can also be seen as a retreatist who rejects both cultural goals and the means to achieve them, so that social withdrawal can be understood as a specific adaptation strategy, based on a way to escape into an unproductive, non-striving lifestyle (Merton Reference Merton1938; Toivonen, Norasakkunkit and Uchida Reference Toivonen, Norasakkunkit and Uchida2011). Indeed, in post-industrialised societies youth transitions have changed radically, with mass transitions replaced by non-linear and more individualised processes (Furlong Reference Furlong2008). Economic stagnation and social insecurity combine with pressures to be (globally) competitive and towards an increasing individualism, as a set of ideas and ideals with a potentially negative impact on mental health, especially among young people (Toivonen, Norasakkunkit and Uchida Reference Toivonen, Norasakkunkit and Uchida2011). On the one hand, unforeseeable careers and irregular employment lead to downward social mobility (Furlong Reference Furlong2008) and to a precarious social status (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lee, Choi and Choi2013); a loss of a sense of direction and the failure to find a place in society may therefore cause disengagement (Furlong et al., Reference Furlong, Goodwin, O'Connor, Hall, Lowden and Plugor2018). On the other hand, the narcissistic characteristics of individualism in terms of being obsessed by the impression produced in others, as mirrors of the self, have been amplified by the intrusive effects of social media (Codeluppi Reference Codeluppi2007; Gentili Reference Gentili2014). According to Kato and colleagues (Reference Kato, Tateno and Shinfuku2012, p. 69), social withdrawal ‘might be an indicator of a pandemic of psychological problems that the global internet-connected society will have to face in the near future’. Along these lines, Piotti (Reference Piotti2020) highlights the role the internet can play to protect the user from the shame of the outside world, while deriving imaginary satisfaction from the gaze of others. In this sense, the internet seems to offer the opportunity to live experiences parallel to real life and to abandon caution, thus allowing the virtual body to do things the real body cannot even hope for. The author states that hikikomori can be considered as the extreme representatives of a lifestyle that is becoming universal; they could be regarded as precursors of a modus vivendi in which the volume of human relationships has become increasingly reduced.

Socially withdrawn youths have been associated with high academic pressure and failure to attain academic and social achievements (Furlong, Reference Furlong2008). Too high academic expectations and competition can lead to crises of confidence in young people when they fail (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Lee, Choi and Choi2013). Moreover, school phenomena such as bullying may make students resentful and distrustful towards their peers (Li, Liu and Wong Reference Li, Liu and Wong2018). Therefore, the decision to adhere to a fantasy dimension (such as manga and videogames) seems the only option to enable inclusion in social interactions, avoiding the ‘gaze phobia’ (Spiniello, Piotti and Comazzi Reference Spiniello, Piotti and Comazzi2015).

Some studies report associations between a low psychological wellbeing and the preference for online social interaction, which, in turn, give rise to negative outcomes associated with problematic or Compulsive Internet Use (CIU) (Caplan Reference Caplan2003; Van den Eijnden et al. Reference Van den Eijnden, Meerkerk, Vermulst, Spijkerman and Engels2008; Nowland, Necka and Cacioppo Reference Nowland, Necka and Cacioppo2018). The mental health implications of excessive internet-browsing, gaming and social networking have been demonstrated in terms of higher depression and stress (Harwood et al. Reference Harwood, Dooley, Scott and Joiner2014; Teo Reference Teo2010). The causal nature of the relationship between low psychosocial wellbeing and CIU, however, still needs further investigation, since it may be bidirectional (Meerkek et al. Reference Meerkerk, Van den Eijnden, Franken and Garretsen2010; Nowland, Necka and Cacioppo Reference Nowland, Necka and Cacioppo2017). According to some scholars, the internet can be used to escape and cope with daily problems (Orford Reference Orford2005; Wong Reference Wong2020) and this could be particularly true for socially withdrawn individuals, because it is a place where the real body is absent or completely transfigured (Spiniello, Piotti and Comazzi Reference Spiniello, Piotti and Comazzi2015). Young people who experience social marginalisation can become attached to online communities to seek solace and solidarity (Wong Reference Wong2020).

Finally, differences across cultures are relevant both in terms of risk factors and of behavioural consequences. In Italy social withdrawal is a recent and fast-growing phenomenon, involving between 60,000 and 100,000 cases since 2010 (Spiniello, Piotti and Comazzi Reference Spiniello, Piotti and Comazzi2015). Initially social withdrawal was studied as a consequence of internet addiction, because this condition is often accompanied by overinvestment on the network, but currently, scholars maintain that abuse of the internet is linked to social withdrawal as a strategy to survive TO an extreme lifestyle (Casale and Fioravanti Reference Casale and Fioravanti2011). However, there is a paucity of literature about the subject: most of what exists are theoretical books or qualitative studies oriented towards underlining the role of dysfunctional family dynamics and of individual risk factors in influencing withdrawal from social life (Spiniello, Piotti and Comazzi Reference Spiniello, Piotti and Comazzi2015; Sulla et al. Reference Sulla, Masi, Renati, Bonfiglio and Rollo2020). Therefore, the more structural and social elements responsible for the widespread increase of the phenomenon are often neglected, such as the strain caused by restricted access to socially approved goals and means (Merton Reference Merton1938; Toivonen, Norasakkunkit and Uchida Reference Toivonen, Norasakkunkit and Uchida2011)

Ricci's comparative study (Reference Ricci2014) underlines the differences between Italian and Japanese hikikomori. Compared to Japan, social withdrawal in Italy seems to be more nuanced; acute social withdrawal, which consists of total reclusion at home, is less common than partial social withdrawal, implying a large number of truancies, but the maintenance of a limited social life outside the family (Spiniello, Piotti and Comazzi Reference Spiniello, Piotti and Comazzi2015). In addition, social withdrawal in Italy is often expressed as school phobia and drop-out, often related to family pressures (Spiniello, Piotti and Comazzi Reference Spiniello, Piotti and Comazzi2015) and particularly to the model of intensive parenthood, also widespread also in Italy (see Naldini Reference Naldini2016; Saraceno Reference Saraceno2016; Cannito, Polini and Scavarda Reference Cannito, Polini and Scavarda2021) which prescribes high competences and parental responsibility for children's educational attainment. Moreover, there is a more common relationship with excessive use of the internet and videogames. The role of the intense bond with the mother, sometimes too strong to enable empowerment, seems to be a common element of both Japanese and Italian cases (Ricci Reference Ricci2014). Finally, the most interesting contributory factor is the conflict between desires and expectations produced by the ideology of consumption and the actual possibilities of realisation, typical of every consumerist society.

Our study investigated an adolescent population in Cuneo, Piedmont: it analysed the risk and protective factors in the area of psychological wellbeing that can play a role in social withdrawal, as well as at the perception of the extension of the phenomenon among adolescents and significant adults, the perceived quality of relationships with parents and friends and school experience, time spent online, the functions and consequences of the use of digital devices in everyday life, and the social withdrawal phenomenon.

Method

Sample

Two distinct samples took part in the study: the first was involved in focus group sessions and the second in a survey.

The first focus group brought together eight young people, aged 16–18 years (six females and two males) and the second one 12 adults: teachers, parents, social and health professionals, educators and local administrators (seven females and five males) recruited through a purposive sampling. The focus group sessions lasted 100 minutes on average.

The survey was administered to all the students attending the second year, or tenth grade, of all the high schools and vocational and training schools in Cuneo. The province of Cuneo is characterised by a young and efficient productive field, linked in particular to the food and wine sectors, low youth unemployment, and a high level of social cohesion, due to the presence of small municipalities. According to the sociological literature, these characteristics would make social withdrawal less likely. However, rates of social withdrawal have been steadily increasing in recent years, causing concern among neuropsychiatric departments (source: ASL Cuneo 1 data).

The town hosts many different high schools, so students come from all parts of the valley that surrounds the city. A total of 1,102 out of 1,207 (i.e. 92% of the population of enrolled students) filled out the questionnaire; those who did not participate in the survey were either absent from school or their parents did not give them permission to participate in the study. The sample was composed of 45% males and 55% females, aged 13 to 20 years (M = 15.21 ± .54); the majority (94%) were of Italian nationality and lived with their parents (97%).

The schools included in the sample are heterogeneous. The percentages corresponding to the schools attended, based on the sample size, were as follows: 50% high school, 33% technical school, 17% vocational school. Therefore we grouped them in two balanced sub-samples: high schools and technical/vocational schools. In Italy, this choice is justified for theoretical and research reasons: each type of school seems to collect students with homogeneous socio-cultural characteristics. In fact, if we were to divide students based on the type of school they attend and the preparation offered according to the ministerial programmes, the result would be the following: those who go into technical and vocational institutes, in theory, should be prepared for early insertion into the working world, whereas those who join high schools, in most cases, postpone their entry into the working world through university studies (Bonino, Cattelino and Ciarano, Reference Bonino, Cattelino and Ciairano2005; Rabaglietti et al. Reference Rabaglietti, Roggero, Ciairano and Bonino2008).

Mixed-methods design

This study used a mixed-methods design, a multiple approach in order to achieve a combination with complementary strengths and no overlapping weaknesses. Qualitative approaches offer in-depth information about a phenomenon, but they may offer information only on a limited number of participants. Quantitative methods, in contrast, allow the engagement of large samples and then the testing of the representativeness of the collected information. Therefore, qualitative methods gave in-depth information on the contextual and social factors related to isolation and withdrawal, with a preliminary identification of risk and protective factors. This information was used to structure a questionnaire to analyse the spread increase of the risk and protective factors within a local population of adolescents and to draw out strategies to prevent and tackle the phenomenon.

Qualitative (phase 1) and then quantitative (phase 2) data were collected and analysed in two consecutive phases: phase 1 relied on the information provided by adolescents and key informants with the objective of comparing different points of view and perceptions about isolation and social withdrawal. The focus groups were unstructured, in line with the explorative nature of the study, therefore the facilitator was not directive and the discussion was guided by an agenda made up of open-ended questions.

Phase 2 used an online survey aimed at investigating the spread increase of the risk and protective factors of the phenomenon, by further studying some areas of the psychological wellbeing of adolescents through different indicators. The latter are related to the perceived quality of relationships with parents and friends and their school experience. Other areas we explored were time spent online, the functions and consequences of the use of digital devices in everyday life, and the social withdrawal phenomenon. We created the self-report questionnaire with Google Modules, which was then filled out by students in the computer labs of their schools from October to December 2017. The questionnaire was made up of 45 questions from three validated scales, with a majority of closed-ended answers. Sociologists and psychologists participated in the construction of the questionnaire.

Measures

The quality of the relationships with mother, father and friends was assessed with three different scales, drawn from Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA, Armsden and Greenberg Reference Armsden and Greenberg1987, validated in Italy by San Martini, Zavattini and Ronconi Reference San Martini, Zavattini and Ronconi2009) which has been considered effective to examine perceived parental and peer security (Van der Vost et al. Reference Van der Vorst, Engels, Meeus and Deković2006). The relationships with the mother and the father are related to an 11-item scale, representing the quality of communication (e.g. ‘I share my problems with my mother/father’), feelings of trust (e.g. ‘My mother/father helps me to know myself better’), and alienation (e.g. ‘My mother/father has her/his own problems, so I do not bother her/him with mine’). Respondents rated their relationships on a 4-Likert scale (1=not at all, 4=very well). The full scale has scores which range between 11 and 44. The internal consistency of both scales is excellent (Cronbach's α=.85 for the mother's scale and .86 for the father's scale). For the relationship with friends, the 12-item scale presents the same items of the previous scales, plus one (e.g. ‘My friends accept me for who I am’), therefore the score of the full scale ranges between 12 and 60. The internal consistency is good (present study, α=.80).

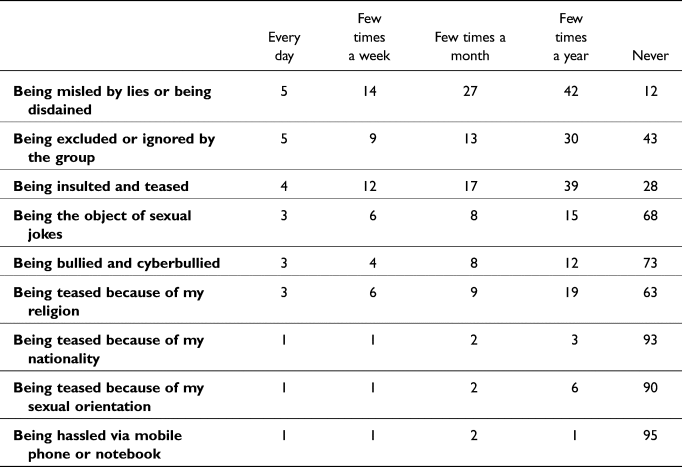

Bullying phenomenon: two scales on bullying have been drawn from WHO's Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Study for Italy (Cavallo et al. Reference Cavallo, Lemma, Dalmasso, Vieno, Lazzeri and Galeoni2014) which refers to the revised Olweus Bullying-Victim Questionnaire (OBVQ, Olweus Reference Olweus1996), one of the most commonly used research instruments in this domain. The focus on frequency, rather than on severity, is useful to estimate the prevalence of bullying and to identify the most widespread forms of bullying, in order to set priorities for prevention (Solberg and Olweus Reference Solberg and Olweus2003). The Olweus questionnaire includes two global items (e.g. ‘How often have you been bullied at school in the past couple of months?’ ‘How often have you taken part in bullying (an)other student(s) in the past couple of months?’), and several specific questions with five response options: ‘never’, ‘only once or twice’, ‘2–3 times per month’, ‘once per week’ and ‘several times per week’. Students who endorse 2–3 times per month or more on two global items are regarded as self-reported victims or bullies, since 2–3 times per month is considered a reasonable cut-off point. Other researchers who investigated the prevalence of bullying with the specific questions from the OBVQ, considered students who endorsed 2–3 times per month on at least one of the items as self-reported victims or bullies (Scheithauer et al. Reference Scheithauer, Hayer, Petermann and Jugert2006). Therefore, we drew from OBVQ specific questions for the two scales: the first one refers to victimisation and the second one to bullying. As far as victimisation is concerned, the 8-item scale covers the seven categories of OBVQ questionnaire plus cyberbullying, according to Berger's revision (Reference Berger2007). It analyses if young people have ever faced such a situation, for example ‘being insulted and teased’ and ‘being misled by lies or being disdained’. Responses ranged from 1 (‘never’) and 5 (‘every day’), therefore the score of the full scale ranges between 8 and 40 and the internal consistency is good (α=.80). As far as being engaged in bullying behaviour, the same situations of the previous scale were investigated, with the supplementary item: ‘Have you ever hit, kicked, pushed or shut-in someone?’. Responses are ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and the full scale ranges between 0 and 9. The internal consistency is acceptable (α=.70).

Time spent on the internet: the 6-item scale on time spent on the internet was drawn from the ESPAD Italy Study (Luppi, Benedetti and Molinaro Reference Luppi, Benedetti and Molinaro2016) which refers to Jia and Jia's study (Reference Jia and Jia2009) and to that of Meerkerk et al. (Reference Meerkerk, Van den Eijnden, Franken and Garretsen2010). Respondents were asked to quantify the hours spent on the Internet, in the last month, considering a typical day: ‘playing online’, ‘gambling or playing with money’, ‘reading, surfing, searching for information’, ‘downloading music, videos, movies’, ‘searching for, selling and buying products’. Responses were 1 (‘none’), 2 (‘half an hour or less’), 3 (‘an hour’), 4 (‘2–3 hours’) 5 (‘4–5 hours’) and 6 (‘6 or more hours’).

The use of social networks: the 8-item scale on the use of social networks has been drawn from the Social Network Survey (Philips and Shibbs Reference Phillips and Shipps2012). Respondents were asked to specify for which activities they use social networks, for example ‘to chat with “friends/users”’, or ‘to search for information or web content’. Responses ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (always).

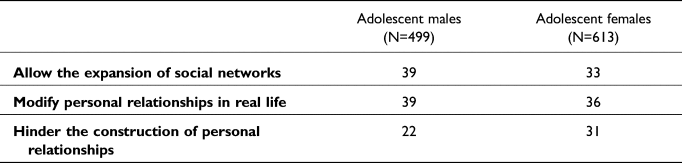

What young people think about the use of smartphones, tablets, computers and social networks: as far as the consequences of the use of digital devices are concerned, we asked respondents to choose between three options: ‘they allow you to expand your social network’; ‘they modify personal relationships in real life’, ‘they hinder the construction of personal relationships’.

As far as social networks are concerned, the response options were: ‘young people give a different self-image’, ‘young people tend to boost their image’, ‘young people are themselves’.

The over-investment of time on the web: two specific scales investigated the excessive use of digital devices: the Compulsive Internet Use scale (CIU, Meerkerk et al. Reference Meerkerk, Van den Eijnden, Franken and Garretsen2010) on the over-investment of time spent on the web, and the scale on the negative consequences of gaming on laptops, tablets and smartphones. CIU or internet addiction, as it is sometimes referred to, is considered a pattern of internet use characterised by loss of control, preoccupation, conflict, withdrawal symptoms, and use of the internet as a coping strategy. The CIU consists of 14 items on a 5-point scale, but we used a 3-point scale (‘‘never’; ‘sometimes’; ‘often’) which scores between 0 and 42. The CIU has a high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha in Meerkek et al. study=.89; in our study=.85). The scale deals with loss of control, preoccupation, conflict, withdrawal symptoms, and coping, with regard to the use of the internet. Sample items are ‘How often do you find it difficult to stop using the internet when you are online?’ and ‘How often do you feel restless, frustrated or irritated when you cannot use the internet?’. Meerkerk and colleagues (Reference Meerkerk, Van den Eijnden, Franken and Garretsen2010, 761) established a cut-off point to dichotomise respondents into non-compulsive and compulsive internet users: ‘this occurs when the behaviour occurs on average more than “sometimes”, which implicates a cut-off score of 14 items × 2 (sometimes) >28.’. Since behaviour should play an important role in the life of the internet user (occurring more than ‘sometimes’) we opted for a more nuanced strategy based on the same ratio (‘compulsive’ or ‘not compulsive’). We created an index of low, moderate and high risk of developing compulsive internet use. The range was 14–42; on the basis of both Meerkerk et al.'s (Reference Meerkerk, Van den Eijnden, Franken and Garretsen2010) cut-off and of the frequency distribution, synthetic indexes were constructed, resulting in the following interpretation: low risk was attributed to young people who scored 14–23, moderate risk to young people who scored 24–33 and high risk to interviewees who scored 34–42.

The negative consequences of gaming on laptops, smartphones and tablets were measured on a scale drawn from the ESPAD Study/Italy (Luppi, Benedetti and Molinaro Reference Luppi, Benedetti and Molinaro2016) which was adapted from Holstein and colleagues’ scale (Reference Holstein, Pedersen, Bendtsen, Madsen, Meilstrup, Nielsen and Rasmussen2014), a short non-clinical measurement tool for perceived problems related to console and computer gaming among adolescents, which showed high face validity and acceptable internal consistency. It is made up of 3 items on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1=‘totally disagree’ to 5= ‘totally agree’) which score between 3 and 15. The items are: ‘I think I spend too much time at playing on console and online games’; ‘I become upset when I cannot play on console and online games’; ‘I have been told I spend too much time at playing on console and online games by my parents’. Even in this case, we created an index of low scores (between 3 and 6), moderate scores (between 7 and 10) and high risk scores (between 11 and 15) which result in developing negative consequences by playing console and online games.

The social withdrawal phenomenon: a dichotomous item response was used to assess respondents’ knowledge of someone who restricted his/her social contacts, to the point of retreating at home (1=yes; 0=no). In case of affirmative response, young people were asked to identify the reasons for social withdrawal, with a dichotomous item-scale, referring to: ‘fail to establish social contacts’; ‘be excluded by peers’; ‘have trouble in school’; ‘have family issues’; ‘be a victim of bullying/cyberbullying’; ‘use videogames or social networks excessively’.

The social withdrawal prevention: the topic has been explored with a dichotomous item-scale (1=yes; 0=no) related to different preventive activities, namely ‘counselling service at school’; ‘open spaces at school’; ‘peer-to-peer initiatives’; ‘information activities’; ‘out-of-school meeting places’; ‘awareness raising initiatives for parents and teachers’.

Data analysis

Data from the survey was analysed with SPSS statistical package version 24. The Chi-Square Test and the ANOVA Test were the main statistical inferential procedures applied, to test the presence of statistically significant differences between subgroups of students, according to gender and type of school (high schools/technical and vocational schools). The ANOVA Test was also used to test the relationship with the two risk indexes of over-investment of time on the web and the other indexes created within the study – relationship with mother, father and friends, bullying, and school experience.

Both focus groups were audio-taped and transcribed, then coded and analysed with Atlas.ti, a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software.

Ethics

The research protocol, the questionnaire and focus group guidelines were written with the social and health professional partners of the project. The research protocol was sent to the head teachers in order to obtain permission to submit the questionnaire to the students. Some schools had to ask for parents’ permission, while other schools already had a general consent from the parents for this kind of study. All interviewees were informed of the research objectives and received assurance that data would remain confidential. Survey participants received parental authorisation to fill out the questionnaires, which were anonymous. Focus group participants’ names were anonymised and interviewees were advised that they could terminate the discussion at any point.

Results

Focus groups

During the focus groups, both adolescents and adults spontaneously mentioned the controversial role of social networks in the development of social relationships, highlighting the so-called ‘shop window effect’ (Codeluppi Reference Codeluppi2007) of social life. For adolescents, the pressures to exhibit and share every social occasion, in order to boost their virtual image, imply the risk of becoming unable to live ‘here and now’.

Instagram and Snapchat stories activity (photos and content that last only 24 hours) often makes you meet friends and do something with them only to exhibit your social life. (16 year-old adolescent female)

Adults, in line with adolescents, maintained that the use of social networks entails being constantly exposed to social judgement; therefore one of the main goals of young people is to gain popularity, no matter how. The use of digital devices is then associated with a greater degree of exposure of private life, shared with a larger group of people than in the past, and with the difficulty of gaining social recognition by the peer group, because of the proliferation of role models.

There have been substantial changes in the type of digital tools used as well as in how fast people can be contacted. … The concept of group and friendship is different and is far more difficult to be socially recognised by others. (Educator)

Teachers, educators and parents suggested the presence of a division between adolescents’ virtual and real social life, with the first represented as a sort of parallel universe, characterised by its own rules, languages and profiles.

Adolescent focus group participants identified excessive internet use as a recurring element in the experience of socially withdrawn friends and acquaintances. The latter are often portrayed as gamers who spend afternoons behind the screen, playing videogames, with other players too. They progressively restrict social life because of their perceived diversity from valued and mainstream role models and lack of self-confidence, which makes socialising difficult and painful.

If they do not appear as cool guys, then it is hard for them to interact with peers and it is easier to do it behind a computer (Male adolescent, 17 years old).

They can also be victims of bullying, manifested as acts of harassment carried out by a group of classmates, who exclude those who are considered to have peculiar lifestyles. Social networks, for some interviewees, could strengthen their understanding of social standards.

Now we tend to be homogenised, thanks to the social networks too: they outline a female/male model to which you have to conform, otherwise you are an outcast. (17-year-old adolescent female)

Adult focus group participants reported situations of partial social withdrawal too, as cases of early school leaving correlated with an excessive use of videogames. Therefore, they confirmed the adolescents’ representation of socially withdrawn young people, but they focused more on family causes. Positive family relationships are represented as a protective factor in social withdrawal, whereas dysfunctional family dynamics are considered risk factors.

Adolescents’ focus on peer relationships and adults’ focus on parents and teachers’ relationships are viewed within a context of prevention: adults mentioned awareness-raising projects for parents and teachers, whereas adolescents suggested student-led initiatives and information activities.

Survey

The perception of school experience and the bullying phenomenon

The majority of the adolescents reported positive school experiences: almost 80% of them liked going to school very much, even if the same percentage found it stressful, particularly girls (M-F: χ2=21.87, p < .0001) and high school students (high school and vocational schools: χ2=23.49; p < .0001). Thirty-five per cent of adolescent females were highly stressed by school workload, whereas only 23% of adolescent males felt the same pressure; parallel to this, 35% of high school students and 23% of vocational students felt greatly stressed by school.

The relationships with teachers and peers showed a similar multi-faceted picture: almost 90% felt accepted by their classmates, boys more than girls, but only 67% considered that they were treated by teachers in the right way, and students from vocational schools were more dissatisfied with their teachers. The type of school matters (Chi-square=9.12; df=3; p=028): 35% of vocational students maintained that teachers do not treat them in a fair way, whereas only 30% of high school students agreed with this statement.

In line with the qualitative results, the quality of the relationships at school was also analysed with regard to the level of increase in bullying. Overall, the phenomenon is not so widespread, both in terms of being directly or indirectly exposed to acts of violence or harassment, and in terms of carrying them out. We focused our attention on the victimisation scale, since it is correlated with social withdrawal, according to the literature (Ricci Reference Ricci2014; Spiniello, Piotti and Comazzi Reference Spiniello, Piotti and Comazzi2015). The mean value of the victimisation is 15, in a range between 8 and 40, therefore the majority of the respondents scored below level 3 (‘to be considered victims of bullying’). However, when reviewing it in more detail, many respondents were familiar with the victimisation problem caused by being bullied: almost 19% of the interviewees reported being disdained, 15% being insulted and teased, 14% being excluded from the peer group and 7% being bullied or cyberbullied on a regular basis. As focus group participants stated, religion, nationality and sexual orientation do not seem to be associated with aggression or exclusion, since episodes related to them were rarely mentioned (Table 1).

Family and friends: the relationship with significant others

In line with the good relationships reported with classmates, interviewees were generally satisfied with their friendships: about 65% of the respondents considered friends as helpful in order to know themselves better; 89% felt accepted and 84% perceived their friends to respect their feelings. However, even in this case contradictions can coexist: almost 30% of the adolescents maintained that they do not talk with friends about their personal problems and the same percentage was indifferent to the quality of relationships with peers. Adolescent females expressed a statistically significant higher level of satisfaction related to friendship than adolescent males: in a range between 12 and 60, the mean value for adolescent females was 49, for adolescent males 46.

The quality of the relationship with parents was equally strong, both with the mother and father, even when assessed separately and with the same scale: only 18% of the interviewees expressed dissatisfaction in this domain. In a range between 11 and 44, mean values for adolescent females was 32.88 with the mother and 30.09 with the father; for adolescent males, mean values were respectively 34.04 and 32.77 (Table 2).

The role of the internet and social media

Adolescents are used to spending a great deal of their spare time online, searching for information, downloading multimedia content, and, above all, using social networks, particularly Instagram and Snapchat. Social networking is an everyday activity for the majority of the survey respondents, which takes between one and three hours a day for half of the sample and between four and six hours for 40% of the students. A factorial analysis on the eight items, with the Varimax method, revealed the presence of two components, with a good proportion of variance explained (58%). The first component consists of ‘chatting with friends/users’, ‘sharing information or web content’, ‘knowing the opinion of other users’, ‘expressing his/her own opinion’, ‘observing/knowing what the other users are doing’, ‘searching for information or web content’, being defined as ‘expressive/social use of social networks’. The second component consists of ‘playing online games with other players’ and ‘playing online alone’, being defined as ‘recreational use of social networks’. Even if the expressive use of social networks was more widespread in the sample, adolescent females presented significantly higher mean values than adolescent males (in a range between 6 and 30, adolescent females’ means are 22, and adolescent males’ 20). Adolescent males, on the contrary, are more keen on recreational use of social networks than adolescent females (in a range between 2 and 10, adolescent males’ mean value is 6, adolescent females’ 4.4).

The excessive use of digital devices. The two risk indexes on the excessive use of internet and videogames outlined a quite problematic situation. The first index, ‘over-investment of time on the internet’, showed that 45% of the adolescents were at either moderate or high risk of developing an over-investment of time online (41% at moderate risk and 4% at high risk).

In addition, 38% of the respondents who said they were playing, were at moderate risk and 16% at high risk of incurring negative consequences of gaming.

Adolescent females are more exposed to the moderate risk of over-investing time online than boys (p =.000), indeed, girls also spend a larger share of time on social media, but they are more critical about their consequences for building relationships in real life: social networks were considered to modify or rather hinder personal relationships for almost 40% of the respondents (30% of female respondents). The differences between mean values of males and females are statistically significant (Chi Square=6.98, df=2; p =.030) (Table 3).

Table 1. Bullying scale (victim part) – Have you ever found yourself in such a situation? (%)

Beyond gender differences, 95% of the respondents stated that a virtual self-image does not correspond to the real one, because young people tend to enhance or change it on social media.

The risk and protective factors of the excessive use of digital devices

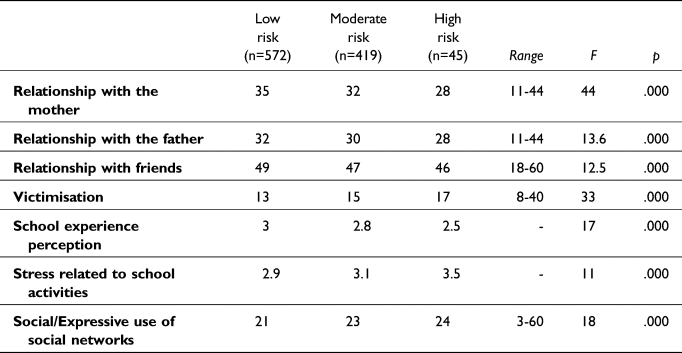

In order to assess the presence of a relationship between the over-investment of time on the web and on digital devices and the psychosocial factors investigated within the survey, we did the ANOVA analysis between the two indexes and the relationships with the mother, the father, friends, bullying phenomena and the two types of use of social networks.

In line with the focus groups results, young people with a lower risk of overinvesting time on the web reported more positive relationships with mother, father and friends than young people with a higher risk. Moreover, young people with a lower risk of over-investing time on the web had a more positive perception of school experience and a lower level of stress related to school activities. This situation is consistent with the bullying phenomenon, because young people who were more engaged in bullying activities or who had been victims of them presented a higher risk of over-investing time on the internet. Finally, a high risk of over-investing time on the web is related to the ‘expressive/social use of social networks’ (Table 4).

Table 2. Relationship with parents (mean, range: 11 and 44) (t-test; *** p < .0001)

Concerning the negative consequences of online and console playing, positive relationships with mother and friends are still a protective factor, related to a lower risk, whereas a positive relationship with the father is associated with a moderate risk in incurring these consequences. Students who reported a positive perception of school experience also presented a lower risk of developing negative consequences of gaming. Stress related to school activities is not significantly related to the risk index. Finally, in line with qualitative findings, students with a higher risk of developing negative consequences of gaming were also more engaged in bullying episodes, both as victims and as bullies, and reported a recreational use of social networks (Table 5).

Table 3. According to you, the use of a smartphone, tablet and laptop… (%)

Table 4. The index of over-investment of time on the web and psychosocial variables (mean, ANOVA)

Table 5. The index on negative consequences of online and gaming console and psychosocial variables (mean, ANOVA)

Social withdrawal phenomenon and how to prevent it

Thirty-five per cent of the survey respondents, particularly adolescent males, from both types of schools, know someone who had a restricted social life, which may include a complete retreat from the rest of the world by staying at home. Differences between males and females are statistically significant (Chi Square=18.6; df=1, p < .0001).

According to the adolescents, the reasons for social withdrawal are a failure to conform to the cultural norms of appearance (beauty, outfit, social life) or to the norms of presentation of self; bullying episodes; the lack of stable role models in the family; and the psychological vulnerability of the individuals. Seventy per cent of respondents mentioned the excessive use of the internet and videogames as a contributing factor to a loss of interest in social relationships.

Discussion

The current study aims to highlight a multi-faceted picture related to risk and protective factors that can foster or hinder social withdrawal phenomenon and to contribute to its understanding. The mixed methods approach allowed us to triangulate and expand findings, and to highlight contradictions.

Social withdrawal is not a widespread phenomenon within the social groups of young people and adults involved in the study. In fact, partial and total social withdrawal cases, even if associated with dysfunctional family dynamics and individual psychological problems, as previous research underlined (Spiniello, Piotti and Comazzi Reference Spiniello, Piotti and Comazzi2015) also seem to be influenced by more structural social and contextual factors (Norasakkunit and Uchida Reference Norasakkunkit, Uchida, Tromsdorff and Chen2012; Furlong Reference Furlong2008).

Furlong's (Reference Furlong2008) theoretical assumptions, then, can be partially confirmed by our empirical study: the effects of non-linear and individualised transitions, paralleled by an increasing level of social insecurity, have been clearly highlighted by our findings. We found both qualitative and quantitative evidence about the main social mechanisms at the basis of isolation and withdrawal: the pressures to be competitive and successful in every adolescent's life context (school, social life, bodily appearance) and the inability to face failure (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Lee, Choi and Choi2013). Consistent with Mark Wong's (Reference Wong2020) claim, online interactions can be a form of response from young people to mitigate experiences of marginalisation and the increased precariousness of work and education in the twenty-first century. Specifically, the failure to conform to cultural norms of appearance on the one hand, and to school performance on the other, seem to be the two sources of stress and social disapproval for adolescents. As Carla Ricci stated (Reference Ricci2014) the inner conflict of the ideology of consumption, in terms of unlimited desires and limited possibilities of fulfilment, has an impact on the construction of young people's identities. Young people who feel unable to keep up with these standards thus have no choice but to withdraw from the competition, by refusing to attend school and ceasing to interact face-to-face with others: i.e., in the face of these pressures, they choose the path of withdrawal in order to conform, rejecting both social goals and the accepted means to achieve them (Merton Reference Merton1938). However, Merton's theory of strain applied to understanding social withdrawal, can benefit from more recent developments that have added a social-psychological level to Merton's focus on social and cultural structures. These developments suggest that tension can arise from the fact that failure to achieve positively valued goals is compounded by an inability to escape painful personal situations (Agnew Reference Agnew1992).

Bullying seems to act as a sort of reinforcement element, being quite widespread and oriented towards young people who differ from mainstream role models, more than towards people with different ethnic and religious backgrounds or sexual orientation. In addition, social media seems to have a fundamental role in strengthening social standards, specifically female and male role models, by producing a constant exposure to social judgement. Social networks expand the audience for the presentation of self in everyday life, hindering the extent to which someone can control how much they may be able to impress other individuals (Hogan Reference Hogan2010; Zucchetti, Giannotta and Rabaglietti Reference Zucchetti, Giannotta and Rabaglietti2013). The aim of becoming popular on social media is a far-reaching objective, which increases competitiveness between young people, pressuring them to engage in extreme behaviour (even bullying) and to face the wider consequences of their actions (Caplan Reference Caplan2003; Van den Eijnden et al. Reference Van den Eijnden, Meerkerk, Vermulst, Spijkerman and Engels2008; Nowland, Necka and Cacioppo Reference Nowland, Necka and Cacioppo2017). Our participants partially confirmed this statement, though the use of social networks, because it is so pervasive in everyday life, was also the object of criticism by survey respondents and adolescent focus group participants, who expressed the same worries about the clash between real and virtual life.

The study suggests that engagement in online activities may undermine participation in offline social life. The two indexes of over-investment of time on the web and on the negative consequences of playing online and playing console games presented a quite problematic situation. Moreover, people who are at higher risk of developing an excessive use of digital devices are more likely to be engaged in bullying, to be more dissatisfied by relationships with teachers and classmates, and to perceive family and friends’ relationships less positively. At the same time, social/expressive use of social networks is associated with an over-investment of time on the web, while recreational use of social networks is related to excessive gaming.

In line with Spiniello and colleagues’ study (Reference Spiniello, Piotti and Comazzi2015) the web, where young people spend a great deal of their time, could represent a shelter for socially withdrawn individuals, a place to join social interactions, with the possibility of choosing between different profiles and identities. The vicious cycle highlighted by some studies, in terms of an association between poor psychological wellbeing and the preference for online interaction, which, in turn, predicted negative outcomes associated with problematic or compulsive internet use (Caplan Reference Caplan2003; Gross et al. Reference Gross, Juvonen and Gable2002; van den Eijnden et al. Reference Van den Eijnden, Meerkerk, Vermulst, Spijkerman and Engels2008; Wong Reference Wong2020), seems to be confirmed by our study. It is extended not only to vulnerable people, but also to a larger part of the population. Considering the wide effects of the identified social mechanism at the basis of exclusion and the everyday frequency of social networking, the phenomenon will probably increase in the near future.

Risk factors (bullying, over-investment of time on the web, negative school experience) are quite clear, whereas protective factors are less undeniable, since only a positive relationship with friends and with the mother is mentioned in focus groups and is related to a low risk of excessive use of digital devices. However, intense bonds with the mother are considered one of the main contributing factors of social withdrawal (Ricci, Reference Ricci2014) and the suggestions about prevention priorities are oriented to the involvement of all significant others, through students’ initiatives and information activities.

Conclusion

The study highlights some areas of concern. Negative school experience, excessive use of digital devices and bullying are widespread in our sample. These are important signals, which, in speculative terms, could be configured as risk factors for social withdrawal among adolescents. Overinvestment of time on the internet is a harbinger of social isolation, as a strategy to cope with social pressures, with the effect of avoiding facing them and producing negative consequences in real life. The identification of protective factors is more controversial: however, the findings demonstrate that school is an important context both for early identification and for facing the phenomenon when the first alarm appears, and teachers and schoolmates can be alerted to detect and bring to light the worrying signs. One of these signs is undoubtedly the difficulty in disconnecting from online activities, gaming and social networks, taking time out for offline social and recreational activities. The majority of the interviewees, when referring to cases of social isolation and disengagement, mentioned the excessive use of videogames and digital devices as a contributing element.

Raising awareness about the phenomenon is crucial, both through student initiatives, i.e. peer education projects aimed at preventing young people's anti-social behaviour and improving their social skills, and involving parents and teachers.

This study had some limitations that need to be mentioned. First, the cross-sectional design precluded the exploration over time of the protective and risk factors on possible social withdrawal paths among adolescents. Second, the questionnaire and the focus group directly addressed the topic of social withdrawal only in limited sections, focusing more on risk and protective factors. Despite the limitations mentioned, findings indicate the need to plan student initiatives to promote and empower psychological and socio-emotional wellbeing, and to remove adolescents from situations of risk of social withdrawal.

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

This work is part of a wider project promoted by Cuneo Municipality: ‘Hikikomori, young people who refuse social relationships. Prevention strategies and mental health promotion of adolescents and their families’. This project had among the partners: local health services (ASL CN1); social care services (Consorzio Socio-Assistenziale del Cuneese); Board of Education (Ufficio Scolastico Provinciale); a social cooperative (Cooperativa Sociale Emmanuele Onlus); a cultural association (Associazione Culturale EsseoessenetOnlus); a voluntary association (Associazione di Volontariato Fiori della Luna Onlus); Eclectica, Institute for Research and Training. The authors wish to thank all the partners, the Department of Psychology at the University of Turin (specifically professors Emanuela Rabaglietti and Antonella Roggero) and the young people and adults who participated in this study. We would like to thank Lynda Lattke for the linguistic revision of the text.

Author contributions

While the paper is the result of several discussions between the authors, Franca Beccaria wrote part of the results (focus groups), and contributed to the writing about the method, the discussion and the conclusion; Alice Scavarda wrote the introduction, the discussion, and part of the results (survey); Emanuela Rabaglietti and Antonella Roggero contributed to part of the introduction, part of the method and the results (survey), and all the authors jointly wrote the discussion and the conclusion.

Funding statement

The project has been supported by the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Cuneo, for the tender Health Prevention and Promotion 2016.

Competing interests

the authors declare none.

Ethical standards

The study is compliant with the ethical standards of our country, in terms of informed consent and respect for the privacy of the participants. All the names have been substituted with pseudonyms and all the sensitive information has been removed from the results session.

Informed consent

All the participants signed (electronically or face-to-face) an informed consent, in line with GDPR guidelines.

Franca Beccaria is a sociologist, and partner at Eclectica,, contract professor at EMDAS (European Master on Drug and Alcohol Studies), University of East Piedmont, Novara. Her main research interests are adolescents, alcohol and culture, prevention, and sociology of health.

Alice Scavarda is a sociologist who worked at Eclectica between 2015 and 2019. She is currently Postdoc Research Fellow at the University of Turin. Her research interests focus on mental health, ageing, disability and addiction.

Antonella Roggero is a psychologist and contract professor of Developmental Psychology at the University of Turin. Her main research topics concern the promotion of psychosocial wellbeing and risk prevention throughout the life cycle.

Emanuela Rabaglietti is associate professor in Developmental Psychology at the University of Turin. Her main research topics focus on social relationships among peers during childhood and adolescence; adolescent risk behaviours; and processes in optimal adjustment of the elderly in normative and non-normative conditions. She was the author of numerous publications on these topics.