In the recently published European Charter on counteracting obesity, Item 2·4·8 stipulates that ‘Action should be aimed at ensuring an optimal energy balance by stimulating a healthier diet and physical activity’. This recommendation specifically draws attention to the issue of energy balance, which demands an understanding of the interaction between physical activity and energy intake (EI). This has both theoretical and practical implications(Reference Blundell, Stubbs, Hughes, Whybrow and King1). More than 40 years ago, the common-sense view implied that ‘the regulation of food intake functions with such flexibility that an increase in energy output due to exercise is automatically followed by an equivalent increase in caloric intake’(Reference Mayer, Roy and Mitra2). Mayer et al. went on to point out the fallacies inherent in such an attitude. Mayer’s own findings demonstrated that physical activity was not invariably coupled to EI, and even produced evidence that very low physical activity (sedentariness) was associated with a high EI. Today, there is considerably more evidence that EI (food consumption) is only weakly coupled to exercise-induced metabolic activity(Reference Blundell and King3, Reference Stubbs, Hughes, Johnstone, Whybrow, Horgan, King and Blundell4). Indeed this may be one example of a more general phenomenon indicating a weak relationship between metabolic variables and food intake or eating patterns.

One possible reason for this is that EI cannot simply be considered as the self-administration of fuel. EI really means eating behaviour, and behaviour is shaped and driven by both biological (under the skin) and environmental (beyond the skin) variables as well as by mental events. Indeed, it can be noted in passing that while behaviour can represent between 20 % and 60 % of energy expenditure (EE), food intake (EI) is 100 % behaviour. These behavioural patterns are held in place by environmental contingencies as well as by more obvious social and cultural influences. The importance of this perspective is that, once a pattern of behaviour is established, it can be maintained independently of many physiological events. In other words, there can be a lack of tight coupling between the behaviour that forms the basis for EI (eating), the behavioural vehicle for EE (physical activity) and the metabolism associated with EE(Reference Blundell and King3).

This loose coupling between EI and EE suggests that physical activity should be a good technique to bring about weight loss. However, the results of exercise trials are frequently disappointing(Reference Bensimhon, Kraus and Donahue5–Reference Garrow and Summerbell7). There may be a number of reasons why this is the case. For example, it is likely that many people make poor evaluations of the amount of energy that can be expended during exercise, and the amount that can be ingested during eating. Indeed, a single bout of exercise can be considered relatively slow method of ‘removing’ energy from the system because the rate of EE (kcal/min) is low. Consequently, the time spent exercising has to be significantly long in order to expend a meaningful amount of energy. For example, to expend 2510·4 kJ (600 kcal), an individual with a VO2max of 3 l/min (medium fitness) would have to exercise for 60 min at approximately 75 % VO2max. Someone with a lower level of fitness may expend only 1046 kJ (250 kcal) for a 60-min session of equivalent intensity. However, any individual (independent of fitness) could consume 2510·4 kJ (600 kcal) of food energy within a matter of minutes. Consequently, there is a biological mismatch between the rates at which the body can ingest and expend energy. It is likely that most people are completely unaware of the energy values of either physical activity or food items, and therefore they fail to make the appropriate adjustments to both of these behaviours that are necessary to achieve a negative energy balance. This is one reason why exercise commonly fails to be a successful method of weight loss. More than 10 years ago, we demonstrated the simple fact that the selection of high-fat (high-energy dense) foods after exercise could completely reverse the negative energy balance created by exercise(Reference King and Blundell8). Therefore, exercise should not be seen as providing permission to abandon any restraint over eating, or to indulge excessively on available foods. The present study has thrown light on how the effect of exercise on weight loss can be optimised.

Design

Fifty-eight overweight or obese men (n 19) and women (n 39) (mean BMI = 31·8 ± 4·5 kg/m2; mean age = 39·6 ± 9·8 years; VO2max = 29·1 ± 5·7 ml/kg/min) completed a 12-week exercise intervention study; subjects exercised five times per week for 12 weeks under supervised laboratory conditions. A sub-maximal exercise test was performed at weeks 0, 4, 8 and 12 to assess the relationship between heart rate (HR) and O2 consumption (Vmax29; Sensormedics, CA, USA). This information was used to prescribe exercise duration at 70 % HRmax to expend approximately 2092 kJ (500 kcal) per session. Each exercise session was performed in laboratory conditions. Subjects wore a heart rate monitor (POLAR, Kempele, Finland) during each session. Body weight and composition, blood pressure, resting heart rate (RHR), waist circumference and cardio respiratory fitness were measured following an overnight fast at weeks 0, 4, 8, and 12. Total daily energy intake was also measured at weeks 0, 4, 8 and 12 using a test-meal procedure with a fixed breakfast followed by ad libitum lunch, dinner and snack box.

Results

Anthropometric variables

For the whole sample, the mean change in body weight and body fat was statistically significant at 3·2 kg (P < 0·001) and 3·2 kg (P < 0·001), respectively. However, when individual data were examined, there was large individual variation in both weight and fat change. The changes in body weight ranged from a loss of 14·7 kg to a gain of 2·7 kg, and fat mass changes ranged from a loss of 10·2 kg to a gain of 1·7 kg (see Fig. 1). This large interindividual variation led to the classification of two distinct groups termed as responders (R) and non-responders (NR). The R were classified as having body composition changes equal to or greater than that expected from the energy expended through exercise. The NR were those individuals whose body composition changes were less than that expected from their total exercise energy expenditure. A 2 × 4 repeated measures ANOVA demonstrated a significant week × group interaction for both body weight (P < 0·001), and body fat (P < 0·001).

Fig. 1 Individual changes in body weight (BW) and body fat mass (FM) at the end of the mandatory exercise programme (![]() , BW;

, BW; ![]() , FM)

, FM)

Energy intake

These observed differences in body weight and body composition between the two groups indicated that some form of compensation was taking place. Figure 2 shows the change (week 0 v. week 12) in total daily energy intake taken from laboratory test meals. The R decreased energy intake over the 12 weeks (−527·1 ± 2186 kJ (−125·9 ± 522·2 kcal)/d), whereas the NR increased energy intake over the 12 weeks (+686·6 ± 2286 kJ (+164·0 ± 545·9 kcal)/d) (t = −2·09, df = 44, P = 0·043). Importantly, an independent t test revealed that the R significantly increased their fruit and vegetable intake from 3·2 to 4·4 portions per day, whereas the NR decreased their intake, over the 12-week intervention, from 3·0 to 2·5 portions (t = +2·96, df = 46, P = 0·005). In addition, NR increased the amount of fat consumed, whereas R did not.

Fig. 2 Measured daily energy intakes (means and se) for the participants who showed good weight loss in response to the exercise programme (![]() ) and those who did not (

) and those who did not (![]() )

)

Health markers

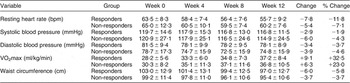

Table 1 shows the observed changes over the 12-week exercise intervention in the measured health markers for both the R and NR. There were significant decreases in RHR for both the R and NR (P < 0·0001), and significant decreases in both systolic (P = 0·003) and diastolic blood pressure (P < 0·0001) for the R and NR. Alongside these changes was a significant increase in cardio-respiratory fitness (P < 0·0001) with no week × group interactions and no main effect of group for any of these variables. There were also significant decreases in waist circumference measurements across the 12-week intervention (P < 0·0001), and a week × group interaction (P = 0·029).

Table 1 Changes in health markers during the exercise programme for participants who showed good weight loss in response to the mandatory supervised exercise regime (responders) and those who did not (non-responders)

Discussion

These data have demonstrated that standardised exercise does not produce the same degree of weight loss for all individuals. In fact, large individual variability was observed, with some individuals displaying marked weight loss (R) while others displayed negligible weight loss or weight gain (NR). Poor and good responders to exercise(Reference Weinsier, Hunter, Desmond, Byrne, Zuckerman and Darnell9) and dietary interventions(Reference Tremblay, Poehlman, Nadeau, Dussault and Bouchard10, Reference Levine, Eberhardt and Jensen11) have been identified previously. These present data raise the issue that exercise alone may not be a fruitful option for weight loss for everyone. The heterogeneity (direction and magnitude) of the responses reported here demonstrates the need to treat individuals rather than the average of a group – one size does not fit all. It also highlights the importance of determining those mechanisms that may explain the variability and why some individuals benefit and others do not. For the majority of the NR, the less than expected weight loss can be explained through an increase in energy intake in response to the increase in the exercise-induced energy expenditure. The NR increased energy intake over the 12-week intervention by 686·176 kJ (164 kcal), whereas the R decreased energy intake by 523 kJ (125 kcal) leading to a 1209·176 kJ (289 kcal) difference between the R and NR. The observed increase in energy intake was through an increase in the energy density of food consumed. This has been described previously as passive over consumption(Reference Blundell, Lawton and Hill12). The increase in the energy intake from the NR could be accounted for by the changes in fruit and vegetable intakes (calculated from the free-living food diary data). The R increased their portions of fruit and vegetables eaten per day from 3·2 to 4·4 portions, whereas the NR decreased their intake of fruit and vegetables from 3·0 to 2·5 (significant difference between the two groups (P < 0·005).

Despite the absence of a meaningful loss of body weight, the NR experienced significant changes in health markers. This indicates that exercise in the absence of weight loss still provides a valuable tool for improving health. There was no significant correlation between the change in either blood pressure or RHR and the change in body weight. Since a reduction of 10 mmHg in systolic pressure or 5 mmHg reduction in diastolic pressure can reduce the risk of a stroke by approximately 35 %, the results observed in this intervention are very promising. These findings again demonstrate that body weight is not the only meaningful outcome of an exercise intervention.

These results have demonstrated that large interindividual variability in physiological responses occurs to the same volume of imposed exercise. Some individuals did not experience the beneficial effects of exercise on body weight, but still showed beneficial effects on health parameters such as waist circumference and body composition. Therefore, regular exercise in conjunction with an increase in fruit and vegetable consumption could be used advantageously to reduce obesity. Exercise alone is not enough; a balanced diet is also required, if optimum weight loss is to be achieved.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBS/B/05079, 2004–2007).