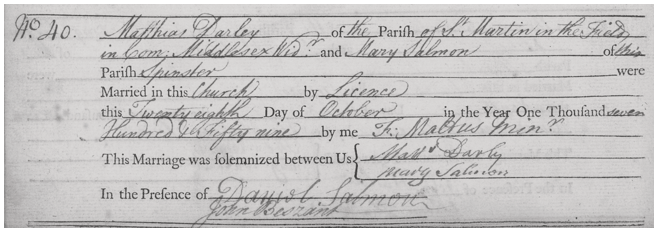

On 28 October 1759 Mary Salmon, aged twenty-three, married Matthias Darly, aged about thirty-eight, at the church of St Mary Magdalene, Bermondsey. She was the daughter of Daniel Salmon, a ferret weaver, and his wife Elizabeth. Ferrets were ribbons or tapes made of silk waste used in furnishings; according to Annabel Westman ferret weaving was a ‘poor man’s trade’.Footnote 1 Four of the Salmons’ children, aged between nine days and fourteen years, had been baptised at St Mary Magdalene on 7 July 1745; Mary’s date of birth was given in the baptismal register as 13 September 1736.Footnote 2 Bermondsey was on the southern edge of London; John Rocque’s 1747 map of London shows that Long Lane where the Salmons lived was flanked on the north side by tanneries (a noxious trade which flourished in the area until the twentieth century) but to the south were market gardens and orchards which would have made life more pleasant. Mary had obviously received at least a basic education: she signed the marriage register with a confident hand (Figure 10.1) while four of the eight brides whose marriages are recorded in the same opening signed only with a cross. The signature allows her hand to be identified plausibly on prints that she was to publish over the next two decades.

Figure 10.1 Marriage record of Matthias Darly and Mary Salmon, St Mary Magdalene, Bermondsey, 28 October 1759.

Matthias, also known as Matthew, Darly is first recorded in September 1735 as the son of the otherwise unknown Thomas Darly of the parish of St Margaret’s Westminster, apprenticed to Umfrevil Sampson in the Clockmakers’ Company;Footnote 3 he would have been about fourteen years old. From the late 1740sFootnote 4 he was working on his own account at addresses west of the City of London around St Martin’s Lane and Charing Cross.Footnote 5

His work always ranged widely: from visiting cards to wallpaper, architectural, and ornament prints, to seals in stone or metal; he also advertised lessons in drawing from early in his career. His best remembered early prints were furniture designs in Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754) and architectural subjects in Isaac Ware’s A Complete Body of Architecture (1755–1757), the latter volume, like other publications at the time, produced with George Edwards.Footnote 6 The suggestion has been made that Matthias might have been responsible for furniture and architectural designs as well as prints, but there is no reason to think this.Footnote 7 In November 1749, he was one of several printsellers who underwent questioning by the legal authorities for selling prints mocking the Duke of Cumberland.Footnote 8 In his statement he mentioned his wife, perhaps referring to Elizabeth Harold whom he actually married later on 28 October 1750 at St George’s Chapel, Mayfair, where clandestine marriages took place before regulations were tightened in 1753; Elizabeth Harold/Darly is not recorded elsewhere. Matthias was clearly not discouraged from publishing further political subjects: evidence discussed in this chapter shows that the political prints that he and Mary published were inspired by conviction, not simply to follow a profitable trend.

Matthias took his freedom of the Clockmakers’ Company in 1759, some seventeen years after he would have been eligible to do so at the end of his apprenticeship. He may have taken his freedom then in order to take on apprentices himself in the Company. Ten apprentices are listed in the Clockmakers’ records as bound to him between 1760 and 1778: Barnabas Mayor, 1760; William Pettit, 1764; John Roberts, 1764; Thomas Scratchley, 1765; John Roe, 1766; William Watts, 1767; John Williams, 1768; William Wellborn, 1771; Thomas Colley, 1772; Thomas, Barrow, 1778.Footnote 9 In 1752 Matthias had paid stamp duty on the fee of £15 that was required for taking William Darling as an apprentice, presumably in some unofficial capacity.Footnote 10

Mary was working with Matthias at least two years before their marriage in 1757 when her name appears as designer and etcher (‘M. Salmon Invt et Sculp’)Footnote 11 on Caesar at New-Market, a print mocking the Duke of Cumberland’s incompetence in his conduct of the war with France. Mary’s name is certainly etched in her own hand, as is the line from the Iliad below the image. These inscriptions are carelessly placed and apparently etched hastily in contrast with the neatly placed title above and the text below, both of which were clearly the work of a trained writing engraver; similar poorly placed lettering is to be seen on a number of later prints in the hand that seems to be Mary’s. Cumberland’s rotund figure and his round featureless face derive from The Recruiting Serjeant,Footnote 12 a caricature published by Matthias in the same year after a design by George Townshend, an aristocratic young military officer who is often credited with introducing the Italian vogue for caricature – the exaggeration of physical features – to political satire in England.

Mary gave birth to their first child on 1 May 1761; three days later the baby was baptised and named after her mother at the church of St Martin in the Fields.Footnote 13 The Baptism Fees Book records the family’s address as Long Acre, the address shown on one of Matthias’s trade cards.Footnote 14 By the time the next two children, Mattina and Matthias, were born in March 1764 and February 1766 the family was resident in the adjacent parish of St Anne Soho.Footnote 15 The move is indicated by a change in the address on a trade card of ‘Darly Engraver’. An early state reads, ‘the Acorn facing Hungerford Strand’, close to St Martin’s church, where Matthias had been recorded in the mid-1750s, but the lettering is altered on a later state to ‘the Corner of Ryders Court, Cranborn Alley, near Leicester Fields’, an address in Soho.Footnote 16

Advertisements for satirical prints to be sold by Mary Darly at the Ryder’s Court address appear in the London newspapers from January 1762 to December 1763. She made it clear that the prints were not only sold at her own shop: they were ‘To be had of Mary Darly, Fun Merchant, in Ryder’s Court, Fleet-Street, and at all the Print and Ballad Merchants in London and Edinburgh. Itinerant Merchants may be served wholesale by the above Caricature Merchant at reasonable Rates.’Footnote 17 Her identity as a publisher was clearly recognised as apart from her husband’s, although Matthias is recorded at the same address. It was normal for women – wives, widows, daughters, sisters, and mothers – to be actively involved in family businesses at the time,Footnote 18 but the fact that Mary’s name is publicised as distinct from Matthias’s is striking. In the case of these early political satires, it may be that Matthias was concerned to avoid prosecution, but this cannot be the explanation for the appearance of Mary’s name as publisher on later prints and in advertisements (see below): it seems reasonable to infer that her role was parallel to that of her husband, that they ran the business in partnership.

The prints attacked the prime minister Lord Bute, and by implication the young George III, and were extraordinarily scurrilous. Their main theme was that Bute was colluding with France and Spain to arrange a peace treaty that would disadvantage Britain, but – like satirists of all periods – Mary added further insults: Bute was accused of corruptly favouring his Scottish countrymen, and it was implied that he had achieved his powerful position because he was the lover of the king’s mother, Princess Augusta. The Princess was likened to powerful women from history whose sexual appetites were believed to have threatened the state: Queen Isabella, who was said to have had her husband Edward II killed so as to take his place with her lover Roger Mortimer; Mary Queen of Scots, accused of intriguing with her lover David Rizzio;Footnote 19 or – in a contemporary example – the promiscuous Catherine of Russia who staged a coup against her husband in July 1762. Parallels are suggested between Bute and historical figures greedy for power from Sejanus who wielded influence over the Roman emperor Tiberius to Macbeth or Cardinal Wolsey. More immediately identifiable as Bute and the Princess were outsize symbols of a boot and a petticoat.

Mary took responsibility for publication of these prints: her name appears on some of them, and she advertised many in the newspapers. A comparison with her signature in the marriage register demonstrates that the writing on many prints is hers. But did she design and etch them? The style of the images and the quality of etching, especially in the writing, varies a great deal: the prints cannot all have been the work of one person. Mary had etched Caesar at New-Market in 1757 and in advertisements she describes herself as ‘Etcher and Publisher’. But the designs for her publications were the work of ‘amateurs’: she advertised in the Public Advertiser on 2 September 1762, ‘Gentlemen and Ladies may have any Sketch or Fancy of their own engraved, etched, &c, with the utmost Despatch and Secrecy’. In this Mary was following her husband: from the mid-1750s, when Matthias published prints after Townshend’s sketches, he had encouraged amateurs to provide ideas for caricatures, a ploy which did a great deal to create a market for such prints in circles where there would have been less interest in designs by professional caricaturists. Horace Walpole, always concerned with social status, gave friends small caricatures printed as cards mistakenly believing the format to have been invented by George Townshend (‘My Lady Townshend sends all her messages on the backs of these political cards’); the series of ‘political cards’ was published by Matthias and George Edwards.Footnote 20

Some prints published by Mary from Ryder’s Court were competently drawn and arranged in coherent compositions, while others were crude visualisations of simple-minded ideas. An instance of a well-planned and executed print is The Scotch Broomstick & the Female Besom, advertised in the Public Advertiser on 2 September 1762, where the relationship of Bute and the Princess is depicted in no uncertain terms. Bute flies through the air on a phallic broomstick towards the Princess’s ‘besom’, a bundle of twigs that she holds in front of her; elegant Scots couples watch the encounter with prurient interest. A week later the Public Advertiser carried an advertisement for a print that was, by contrast, clearly devised by someone with no artistic training who had presumably provided a rough sketch to be copied:

Tit for Tat, or Kiss My A[rs]e Is no Treason, etched in the O’Garthian Stile, by the Author of the Political History, from the Year 1756 to 1762, and published by Mary Darly, in Ryder’s Court, Leicester-Fields. Where may be had, complete Sets of all the new Political and Droll Prints that are within the State of Decency and true Humour.

The unknown Lady must excuse the Alteration of the Labels, as the Publisher intends to please, not to offend.Footnote 21

The suggestion is that the ‘Labels’, or speech balloons, in the original sketch by an anonymous ‘Lady’ were even more offensive than those in the print where a Spaniard, a Dutchman, and a Frenchman discuss how they must kiss Bute’s bare buttocks as he bends forward to kiss the Princess who has pulled up her skirts revealing the ‘way to favour’. To the left of the print stands William Hogarth with a painting of a boot and thistle that is to take the place of a portrait of William Pitt who had lost power and influence to Bute.

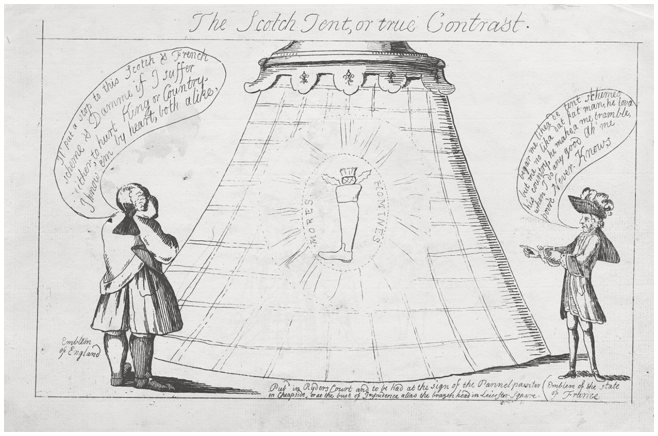

The ‘battle in prints’ extended beyond politics to the art world. William Hogarth, by then an established figure in his sixties, had come into conflict with the younger generation a few years earlier when he opposed their ambitions to found a royal academy. Mary may have been additionally provoked by Hogarth’s long-standing denigration of ‘caricatura’ as opposed to ‘character’.Footnote 22 A new assault on the older artist followed his publication on 7 September 1762 of The Times Plate 1,Footnote 23 a print supporting Bute and the king in their aim to end the war. Mary’s contribution to the attacks on Hogarth included at least three prints: Tit for Tat, described above; The Scotch TentFootnote 24 (Figure 10.2) which was lettered in Mary’s hand, ‘Pubd in Ryders Court and to be had at the sign of the Pannel painter in Cheapside [the print shop of John Smith where the sign was Hogarth’s head], or at the bust of Impudence alias the brazen head in Leicester Square [Hogarth’s home]’; and The Boot & the Block-Head,Footnote 25 where Bute’s boot is suspended from Hogarth’s ‘Line of Beauty’. It is interesting to note that Hogarth’s house was only about 300 yards from Ryder’s Court, and that Princess Augusta lived even closer at Leicester House. Mary’s market for these prints would have been the courtiers and politicians who visited both houses.

Figure 10.2 Mary Darly (publisher), The Scotch Tent, or True Contrast, 1762.

The prints, especially those attacking the Princess, must have caused serious offence. It is possible that Matthias was the ‘famous printseller’ who was indicted at Westminster Quarter Sessions in October 1762 ‘for vending in his shop divers wicked and obscene pictures tending to the corruption of youth and the common nuisance’ and, the following January, was fined £5 and bound over for good behaviour for three years.Footnote 26

Mary took a new commercial approach to caricature at this time by producing the first ‘how-to’ book in English. She advertised in the Public Advertiser on 2 October 1762:

This Day is Published, Price 4s. neatly stitched, Volume I, The Principles of Caricatura Drawing, on sixty Copper Plates, laid down in so pleasing and easy a Manner, that a young Genius may with Pleasure draw any Carick or droll Phiz in a short Time … To be had of Mary Darly, in Ryder’s Court, Cranbourne Alley, Leicester Fields; and at all the Print & Booksellers. Gentlemen & Ladies willing to have any Carick introduced, may send their Sketches as above, for the second Volume, and have them either Engrav’d, Etch’d or Dry-Needled, by their humble Servant.

This was an important change of focus. The images Mary was advocating in this little book were no longer symbols mocking well-known figures, like the round blank face of the Duke of Cumberland, Bute’s boot, or Princess Augusta’s petticoat. She was now directly addressing ‘Gentlemen & Ladies’ and providing guidelines and examples for creating humorous images:

Observe what sort of a line forms the Phiz or Carrick, you want to describe wither its straight lined, Externally circular, internally circular, or Ogeed, when you have found out the line, then take notice of the parts as to their situation, projection & sinking, then by comparing your observations with the samples in the book delineate your Carrick …Footnote 27

These principles can be seen in the innovative prints produced by the Darlys ten years later in their series of ‘Macaronies’ (see below). Meanwhile they continued opposition to government policy, supporting John Wilkes and his campaign against Bute and the peace treaty.Footnote 28 Matthias was a witness to threats on Wilkes’s life from a disgruntled Scottish soldier, Alexander Dun. His letter warning Wilkes of the danger, written on 7 December 1763, was published in the London newspapers over the next few days, and on 16 December 1763 the Gazetteer and London Daily Advertiser carried the following advertisement:

This day at Noon will be published, Price 6d. The Scotch Damien;Footnote 29 a True Portrait of a Modern ASASSIN [sic] drawn from the Life at the Parliament Coffee-House, by a GENTLEMAN in Company: To be had of Mary Darly, at the Acorn, in Ryder’s-Court, Leicester Fields.

The dynamic image of the snarling Dun wielding a large knife is one of the most impressive of Mary’s publications, drawn and etched with skill.Footnote 30

The Darlys again rallied to Wilkes’s support four years later when he returned from self-exile in France. In a letter to the Gazetteer and London Daily Advertiser on 21 March 1768 Matthias, proudly declaring his status as ‘Citizen and Clockmaker’, celebrated Wilkes’s stand against general warrants and recalled how he himself had suffered under such a warrant.Footnote 31 Two months later he advertised a large mezzotint portrait of Wilkes,Footnote 32 and on 13 June he published The Scotch Victory showing the shooting of William Allen by Scots Guards in the aftermath of rioting by Wilkes’s supporters in St George’s Fields, Southwark.Footnote 33 In April 1770, Matthias marked Wilkes’s release from prison with ‘A New patriotic Song, to the Tune of Rule Britannia’.Footnote 34

By 3 August 1765 the Darlys had moved back to the parish of St Martin in the Fields: the Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser advertised ‘an additional volume’ to Colen Campbell’s Vitruvius Britannicus; subscriptions were to be taken by the authors John Woolfe and James Gandon and ‘at Mr. Darly’s, Engraver, in Castle-Street, Leicester-Fields’.Footnote 35 In 1766, the Darlys moved to No. 39 Strand, on the corner of Buckingham Street, announcing the change of address in the Daily Advertiser on 24 June 1766. Their next child, William, was born on 28 August 1767 and baptised on 12 September 1767, but he lived less than five months and was buried at St Martin in the Fields on 25 January 1768. A daughter, Ann, was born on 21 March 1770 and baptised at St Martin’s on 15 April 1770.

The Darlys remained at this address for nearly fifteen years. Matthias continued, as throughout his career, to engrave and publish a wide range of material. Mary advertised the sort of cards that were essential for elite communications, advertising in the Public Advertiser on 3 April 1767:

To the Nobility. Dignified Message and Compliment Cards, so embellished that the different Degrees of Nobility are expressed in a Series of new invented Ornaments adapted to the Duke or Duchess, and down to the lesser Dignities of Peerage. The common Cards of the Shops being ornamented alike, prevents the necessary Distinction of Quality.

To be had of Mary Darly, the Inventress, at No. 39, facing New Round Court, Strand. Where nobility wanting Quantities for Routs, &c. may be served on the shortest Notice, and on the same Terms as the common printed Cards.

N.B. Ornamental Drawings made for the above Purposes in any Taste, and neatly engraved and printed. Where may be had Variety of Ornaments for Print Rooms.Footnote 36

On 13 June 1769, the Public Advertiser carried an advertisement listing the many sorts of printed material available from Matthias at 39 Strand, with an additional note indicating that Mary had found another way to attract female clients: ‘Ladies Stencils for painting Silks, Linens, Paper, &c. by Mary Darly, with the finest Colours’. Such appeals to a genteel market appeared regularly over the next few years, as well as advertisements for artists’ materials and offers of instruction for amateurs; an example in The Morning Chronicle, 4 April 1775 reads, ‘Mrs. Darly’s best respects wait on the Ladies, to inform them, that she has a new assortment of stencils, for painting silks, linen, &c. for work-bags, toilets, gowns, &c. with fine prepared colours, pencils, and every other article used in the polite arts of drawing, painting, etching, and engraving. N.B. Young ladies and gentlemen, (unacquainted with drawing) taught to paint in a few minutes.’

In the later 1760s the Darlys produced fewer political subjects, concentrating for the most part on decorative prints, but in 1771 they embarked on a venture that was to bring them great success. They returned to caricature, this time mocking individuals rather than as part of a political campaign. It was probably their association with Henry William Bunbury that opened the Darlys’ eyes to a new market for humorous prints. They had long encouraged amateurs to supply designs, but Bunbury was far more talented than most amateur artists and he had returned from a tour of France and Italy with sketches that were undoubtedly marketable: peasants, servants in coaching inns, and people – rich and poor – seen on the streets of Paris. On 1 February 1771, the Darlys published a large print based on a drawing by Bunbury entitled The Kitchen of a French Post House / La cuisine de la poste, noting in the lower margin that they also stocked ‘Mr Bunbury’s other Works’.Footnote 37

On 18 November 1771, the Darlys advertised in the Public Advertiser: ‘In a few Days will be published, the first Volume of 24 Caricatures, neatly stitched in blue Paper, by several Gentlemen, Artists, &c. &c.’ These were small caricatures of individual figures, measuring about six by four inches, sold at sixpence plain and one shilling coloured, while octavo volumes containing twenty-four prints were priced at nine shillings plain or fifteen shillings coloured. There were eventually six such volumes, published over two years.Footnote 38 From 1771 onwards the Darly prints are usually offered ‘plain’ or, at a higher price, ‘coloured’ (sometimes the term ‘illuminated’ is used). Earlier prints, such as The Recruiting Serjeant and Caesar at New-Market, had been coloured using stencilsFootnote 39 but in surviving examples from the later period a wider range of colours has been applied freehand.

The series was by far the most successful of the Darly publications and the prints survive in many impressions, often reprinted. An advertisement in the Public Advertiser, 2 November 1773, boasted that the volumes had received ‘great Encouragement … in France, and other Parts of Europe and America;Footnote 40 besides the kind Reception it has met with in Great-Britain’. One print, at least, was sent as far as China: The Stable Yard Macaroni, a caricature of the Earl of Harrington, was copied in Canton – presumably on commission – as a glass painting.Footnote 41

A number of Bunbury’s French peasants appear in the first volume of the series, but the favourite subjects were ‘Macaronies’, the term that was used for foppish young men who sported effeminate fashions and extravagant hairstyles. Title pages for Volumes II to VI read (with slight variations) Caricatures, Macaronies & Characters by Sundry Ladies Gentlemen Artists &c. Subjects range from the Duke of Grafton (A Turf-Macaroni, vol. I, no. 12) to Joseph Banks (The Fly-Catching Macaroni, vol. V, no. 11) to Christopher Pinchbeck (Pinchee, or the Bauble Macaroni, vol. V, no. 24).Footnote 42 Mary Darly herself was said to be one subject, identified by Horace Walpole in an annotation on his impression of The Female Conoiseur [sic] (vol. II, no. 7).Footnote 43 Although political subjects were avoided there are at least two exceptions that reflect the Darlys’ own views: Alexander Murray, the officer charged with the murder of supporters of John Wilkes in the riots of 1768 (The Tiger Macaroni, or Twenty More, Kill’em, vol. II, no. 2), and Robert Clive (The Madras Tyrant or the Director of Directors. JOS or the Father of Murder, Rapine &c, vol. III, no. 21).

In July 1772, around the time of the publication of the third volume, Edward Topham, a young amateur, designed a street view of 39 Strand with the title The Macaroni Print Shop; passers-by – themselves caricatured – laugh at prints displayed in the window.Footnote 44 Another view of the shop, perhaps by Matthias, shows it in 1775 under attack from William Austin, a rival caricaturist and drawing master.Footnote 45

The success of the octavo ‘Macaroni’ volumes led the Darlys over the next few years to collect their prints into quarto volumes.Footnote 46 A surviving title page, dedicated to David Garrick, has the publication line, ‘Pubd. by Mary Darly Jany. 4 1776, according to Act of Parlt. (39 Strand)’.Footnote 47 Whereas the octavo prints had been conceived as a series, these larger volumes were compilations of prints published at different dates in the 1760s and 1770s, and included small prints printed two or three to a page. In 1778 the Darlys advertised another series: twenty-six so-called Bath Cards at one guinea, coloured, ‘to be had of the print and booksellers in Bath, Bristol, and every city and town in Great Britain and Ireland’.Footnote 48

The Darlys also found a novel way to bring customers to their shop. On 28 April 1774, one column of the Public Advertiser carried three notices of exhibitions: those of the Society of Artists and of the Incorporated Society of Artists of Great Britain, and ‘Darly’s Comic Exhibition’. The two Societies and the Royal Academy had introduced art exhibitions to London in the 1760s, but the Darlys seem to be the first to hold commercial print exhibitions, anticipating those of William Holland and Samuel Fores by fifteen years or more. The advertisements published in 1774 suggest that this was their second exhibition. Admission was ‘One Shilling each Person, with a Catalogue gratis, which entitles the Bearer to any Print not exceeding One Shilling Value. This droll and amusing Collection is the Production of several Ladies and Gentlemen, Artists, &c. &c. and consists of several laughable Subjects, droll Figures, and sundry Characters, Caracatures, &c. taken at Bath, and other watering Places …’Footnote 49 Exhibitions continued for several years: the title page of a catalogue from 1778Footnote 50 states that it included ‘near five hundred paintings and drawings’; 323 items are listed of which 212 were by ‘Artists’, sixty-nine by ‘Gentlemen’ and twenty-six by ‘Ladies’.

The Morning Chronicle listed ‘distinguished personages’ who attended on the opening day in 1774, and later reported ‘the inconvenience arising … from the great concourse of the coaches of those real patrons of the polite arts, who attend [Darly’s] exhibitions …’.Footnote 51 Although such newspaper notices were doubtless puffs, the Darlys were certainly well known in London’s cultural world. In the winter of 1773 Matthias’s name appeared in newspaper articles concerning the long-running theatrical dispute between Charles Macklin and David Garrick,Footnote 52 and among many prints of actors is an etching of Garrick in his famous role as Abel Drugger in The Alchemist, lettered, ‘Mary Darly fc et ext’.Footnote 53 There are references to Darly prints in three of the period’s most successful plays: Oliver Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer (1773), Act IV, ‘I shall be laughed at over the whole town/I shall be stuck up in caricatura in all the print-shops. The Dullissimo Macaroni’; Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s The Rivals (1775), Act III, ‘an’ we’ve any luck we shall see the Devon monkeyrony in all the print-shops in Bath!’; George Colman’s prologue to Garrick’s Bon Ton (1775), ‘To-night our Bayes, with bold, but careless tints, /Hits off a sketch or two, like Darly’s prints’.Footnote 54

By the late 1770s there was a new political subject: the American War. The Darlys published a number of satirical prints in a style that by then was conventional,Footnote 55 but they also produced more inventive images. The current fashion for enormous women’s hairstyles was already a subject for satire and they adapted the genre to show hairstyles illustrating events in the war. The Ipswich Journal reported on 11 May 1776 that a lady had been seen ‘with her head dressed agreeable to Darly’s caricature of a head, so enormous, as actually to contain both a plan and model of Boston, and the provincial army on Bunker’s Hill &c.’; this would have been a puff for the Darlys’ recent print, Bunkers Hill or America’s Head Dress.Footnote 56 On 24 October 1776, the Public Advertiser advertised ‘A New Head-Dress, called, Miss Carolina Sullivan, 6d plain, 1s. illuminated’. This was another caricature of an enormous hairstyle decorated with flags, tents, and cannon. Its full title, Miss Carolina Sullivan One of the Obstinate Daughters of America, 1776,Footnote 57 alludes to the unsuccessful attack by the British on Sullivan’s Island near Charleston, South Carolina on 28 June 1776. It was designed by Mattina Darly, then aged twelve, and published on 1 September 1776 by ‘Mary Darly 39 Strand’.

Other prints by Mattina include two satires on the historian Catherine Macaulay and her friend Dr Thomas Wilson both published on 1 May 1777,Footnote 58 and, according to an advertisement in the Public Advertiser on 16 June 1778, ‘Etruscan Profiles … being the Remains of a few sent sometime past to America, and is reckoned a strong Likeness of the great Earl of Chatham, the larger Size at 5s. another at 2s.6d. and an inferior Sort at 1s’.Footnote 59

A print published on 20 February 1779, Banyan Day or the Knight Befoul’d, showing the unpopular Sir Hugh Palliser being thrust into a cooking pot by disgruntled British sailors is lettered, ‘Pub by Tho[ma]s Gra[ham]. Colley at MDarly’s 39 Strand’. Colley had been bound as an apprentice to Matthias on 7 July 1772 and in 1779 he would have been barely out of his apprenticeship, but the previous October he had married Mattina, his master’s daughter, by then fourteen years old; their first child was born the following May.

By now the careers of Mary and Matthias were drawing to an end: Matthias was gravely ill. On 14 June 1779 the Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser carried an advertisement for a sale to be held on 29–30 June at 39 Strand of the ‘extensive stock of prints and drawings, together with twelve hundred copper plates … also, the household furniture, fixtures and various effects, late the property of the well-known ingenious Mr Matt. Darly, Printseller. At twelve o’clock the first day will be sold, the leasehold premises, held for an unexpired term of 19 years, at a moderate rent.’ Three weeks after the sale, ‘The original Sketches from Nature, and high-finished drawings by ladies and gentlemen artists, purchased at Darly’s sale’ were exhibited at 108 Oxford Street.Footnote 60 Later states of Darly prints that carry the publication lines of other publishers would have been made from plates purchased at the sale: an example is, Mr Sharp and Mr Blunt, first published by the Darlys on 1 July 1773 but appearing with the publication line of the partnership of Robert Sayer and John Bennett at some time before 1784.Footnote 61

Matthias died of consumption on 25 January 1780.Footnote 62 However the family did not leave 39 Strand immediately after the sale. Matthias was reported to have died there, and the address continued to be recorded on prints until at least October 1780. Later in 1780 and in 1781 Mary also published a few prints from 159 Fleet Street.Footnote 63

Domestic politics were again a subject for prints with the campaign of Lord George Gordon and the Protestant Association against the relaxation of anti-Catholic laws. The Royal AssFootnote 64 which has a publication line in Mary’s hand, ‘Pub accg. to act May 20.1780. by M Darly (39) Strand’, appeared two weeks before London erupted in the violence of the Gordon Riots. In Lord Amherst on Duty,Footnote 65 published on 12 June, she attacked the lethal military response to the rioting. Amherst’s cry, ‘If I had Power, I’d kill 20 in a Hour’ echoes the caricature of Alexander Murray (‘Macaronies’, vol. II, no. 2, see above).

The fact that Mary continued to publish political prints after Matthias’s death indicates that she was as concerned with the business and with public events as her husband had been. The Darly enterprise was always a joint one. Mary’s name appears frequently in advertisements and publication lines: her role was not merely to ‘mind the shop’. The varied style of images and lettering indicates that many hands were involved in the production of the Darlys’ prints: Mary, Matthias, their apprentices, the journeymen who would have been employed from time to time, and the Darly children as they grew up.Footnote 66 It can be assumed that Matthias and his trained apprentices were skilled printmakers, but the clumsy drawing and lettering of some prints shows that they were etched by untrained hands. The 1779 sale included 1200 copperplates. Although these were not the sort of intricately engraved plates that took weeks or months to produce, the number nevertheless indicates a huge output. Many hands would have been involved in engraving and etching the run-of-the-mill decorative material that made up a large proportion of their work (see advertisements referred to above as well as Matthias’s trade cards, for instance British Museum, 2011,7084.68 and D,2.3238), while the need to produce topical subjects at speed meant that less able printmakers sometimes assisted with the production of caricatures and political prints.

The prints never approach the quality of those produced by the next generation in the 1780s and 1790s when satirical printmaking reached its apogee. However, the Darlys’ role in the development of the genre and its market was crucial. Dorothy George gave them credit as the pioneers: ‘The transition that outmoded the emblematical print and prepared the way for Gillray and Rowlandson was due chiefly to Matthew Darly and his wife. From 1770 to 1777 or 1778 they dominate the print-selling world with caricatures in the newer manner’.Footnote 67 The Darlys’ use of colour on satirical prints also heralded what was to become the norm by the mid-1790s.

In the early 1780s Mary’s circumstances declined rapidly as business collapsed. On 18 December 1783 she applied for poor relief from the parish. The official record of her application makes sad reading:

Mary Darley [sic] aged 44 years lodging at Mr. Green’s No.55 Bear Yard by Lincolns Inn Fields On her Oath saith That she is the Widow of Mathias Darley who died four years ago, That since the death of her said husband she this Examinant lived in and rented an house the corner of Newton’s Court in Round Court in the Parish of St Martin in the Fields for the space of Six months at the yearly rent of twenty four pounds besides taxes, quitted the same about one year and an half ago, That she hath not kept house rented a tenement of ten pounds by the year nor paid any Parish taxes since, That she hath one child living by her said Husband to wit Ann aged thirteen years and upwards now with this Examinant which said Ann never was bound an Apprentice nor was a yearly hired servant in any one place for twelve months together.Footnote 68

Five years later, on 23 February 1789 Mary was admitted to St Martin in the Fields workhouse where she remained until her death on 26 February 1791.Footnote 69 She was buried in the churchyard of St Martin’s on 1 March. According to Jeremy Boulton it was extremely unusual for workhouse residents to be buried there and this indicates some element of status and financial support. A fee of £1.18s.10d. was paid for the burial, as it had been for that of Matthias’s burial eleven years earlier.Footnote 70 It seems likely that Matthias junior, aged twenty-five and now in business as an engraver in nearby Chandois Street,Footnote 71 and Mattina, aged twenty-six and living with Thomas Colley and their children in Portsea, had paid for the long-term medical care that would be available to their mother in the workhouse. The cause of Mary’s death, recorded as ‘Decline’, suggests a lengthy illness.

Mattina’s will dated 6 February 1840Footnote 72 indicates that she and Thomas Colley prospered: by then widowed and living in George Street, Plymouth, she left a house near Portland Square, Plymouth, and sums of several hundred pounds each to her sons John Long Colley and Thomas Graham Colley and her daughter Mary Colley. John and Thomas junior had been established in the trade of their parents and grandparents since at least 1823 when they were recorded as ‘engravers and copperplate printers’ at 4 Union Street, Plymouth.Footnote 73