“[T]he move into mainstream America always means buying into the notion of American blacks as the real aliens.”

—Toni Morrison (Reference Morrison1993)In America’s racial hierarchy, whites are placed atop the order, with greater power and prestige, whereas minority groups are arrayed below (Masuoka and Junn Reference Masuoka and Junn2013; Sidanius and Pratto Reference Sidanius and Pratto1999; Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979). Previous scholars have studied how hierarchies are created and sustained. We know hierarchies are produced by in-groups who actively enshrine themselves politically (Sidanius et al. Reference Sidanius, Feshbach, Levin and Pratto1997). We also know these efforts are facilitated by marginalizing out-groups socioeconomically (Tajfel Reference Tajfel1981). Finally, we know hierarchies persist because dominant groups have weak incentives to relent on the ideological and material benefits they accrue from being atop (Jost Reference Jost2019). Yet this research overwhelmingly centers on dominant groups, leaving us less certain about how subordinate groups reinforce hierarchies and whether it matters politically.

One major reason for this is weak theories about minority groups (Pérez and Kuo Reference Pérez, Crystal and Bianca2021). Although it is intuitive that dominant group members will buttress their rank in a hierarchy, less straightforward are the unorthodox incentives that subordinated groups face to prop a system that marginalizes them (Jost, Banaji, and Nosek Reference Jost, Banaji and Nosek2004). Solving this challenge requires at least two innovations. The first one demands fuller recognition that, despite their collective subordination, minority groups vary sharply in the type of discrimination they face (Bobo and Hutchings Reference Bobo and Hutchings1996; Hutchings and Wong Reference Hutchings and Wong2014; Zou and Cheryan Reference Zou and Cheryan2017). In the United States, although African Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinos are subordinated with respect to whites, the sources of this subordination differ appreciably (Pérez and Kuo Reference Pérez, Crystal and Bianca2021). Consider that whereas Blacks and Latinos are deemed “lower status,” Asians are stereotyped as “superior,” which means they are positioned closer to whites in some respects (Kim Reference Kim1999). Thus, some people of color might cope with their subordination through strategies based on their unique vulnerabilities. For example, during earlier U.S. immigration waves, the Irish and Italians were initially viewed as “undesirable” and similar to Black people. Yet these groups gained greater acceptance from mainstream society by creating psychological and physical distance from Blacks (e.g., via prejudice, segregation; Roediger Reference Roediger2006). In fact, recent work shows prejudice is strongly correlated with Latino opposition to Black-centered policies (Krupnikov and Piston Reference Krupnikov and Piston2016), suggesting a comparable dynamic.

These insights align with other research showing that groups in closer psychological or social proximity to each other will sometimes work hard to distinguish themselves from other out-groups to affirm their own in-group’s uniqueness (Brewer Reference Brewer1991; Branscombe et al. Reference Branscombe, Ellemers, Spears, Doosje, Ellemers, Spears and Doosje1999). This enables in-group members to bolster their own positive sense of collective worth, which buffers against their stigmatization (Crocker and Luhtanen Reference Crocker and Luhtanen1990). For example, Pérez and Kuo (Reference Pérez, Crystal and Bianca2021) show that although Latinos and Blacks are both pegged by society as inferior minorities, Black individuals see themselves as a more American minority (Carter Reference Carter2019), which can drive them to express exclusionary attitudes toward Latinos as a way to distinguish themselves from this other lower status out-group (Craig and Richeson Reference Craig and Richeson2018). This pattern dovetails with classic work on in-group favoritism (Tajfel Reference Tajfel1981), where awareness of an out-group triggers comparisons that enable in-group members to differentiate themselves from “others” in order to place themselves in the most positive light possible.

A second innovation needed to solve this theoretical puzzle is the isolation of psychological incentives that hierarchies provide stigmatized individuals to express prejudice toward other minority groups (Zou and Cheryan Reference Zou and Cheryan2017). Prior work reveals that hierarchies renew themselves by allowing members of subordinated out-groups limited entry to a dominant in-group (Ellemers and Jetten Reference Ellemers and Jetten2013). This grants provisional access to new entrants while retaining the in-group’s distinctiveness (Brewer Reference Brewer1991). It also legitimizes intergroup inequities by “proving” that dominant in-groups are permeable (Jost Reference Jost2019). A contemporary example of this dynamic involves Americans, a high-status in-group defined by white people, their norms, and their behaviors (Devos and Banaji Reference Devos and Banaji2005). Although many people of color lay claim to being American (Carter Reference Carter2019; Silber Mohammed Reference Silber Mohamed2017), they are relegated to the periphery of this in-group because it is alleged that they weakly display the many (white) attributes that define “real” Americans (Zou and Cheryan Reference Zou and Cheryan2017). This marginal position can cause some people of color to feel insecure about their belonging in the category, American. This aligns with seminal work by Bobo and Hutchings (Reference Bobo and Hutchings1996) on how a sense of racial alienation animates intergroup conflict (Hutchings et al. Reference Hutchings, Wong, Jackson, Brown, Charles, Gerken and Kang2011). When members of a racial minority feel socially rejected, they are more inclined to see other groups—including other racial minorities—as threats. When these insecurities become salient, it is plausible that marginal in-group members will be motivated to affirm their tenuous inclusion in a group, which includes the derogation of out-groups (Noel, Wann, and Branscombe Reference Noel, Wann and Branscombe1995).

Theory and Hypotheses: Pinpointing Why, When, and Who

We develop here our own theory, taking care to explain how our thinking builds on prior work. Published research on interminority relations generally highlights the role of contact between groups, demonstrating its reliable association with reductions (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2015) and increases (McClain Reference McClain1993; McClain and Karnig Reference McClain and Karnig1990) in interminority tensions. The heightening of interminority conflict is often traced to imbalances in economic opportunities, political power, and social prestige (Bobo and Hutchings Reference Bobo and Hutchings1996; Carter and Pérez Reference Carter and Pérez2016; Masuoka and Junn Reference Masuoka and Junn2013; Sidanius and Pratto Reference Sidanius and Pratto1999). Indeed, a major source of interminority tensions is the presence of material competition, real or perceived (McClain et al. Reference McClain, Lyle, Carter, Soto, Lackey, Cotton, Nunnally, Scotto, Grynaviski and Kendrick2007). Published work also highlights the role of in-group identities as another force behind competition versus solidarity between communities of color (Benjamin Reference Benjamin2017; Pérez Reference Pérez2021; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2015). Classic work suggests the mere salience of identities triggers in-group favoritism (Tajfel et al. Reference Tajfel, Henri, Billig and Claude1971), which highlights why interminority comity falls apart. But as Wilkinson (Reference Wilkinson2015) and others suggest (Benjamin Reference Benjamin2017; Pérez Reference Pérez2021), some nonwhite identities are compatible, especially when elites highlight shared attributes and experiences between them.

Our framework synthesizes these insights to chart a new theoretical path, which centers on the position of Latinos and Blacks within America’s racial hierarchy and how competition over belonging in a shared group (i.e., American) can undermine comity between them, net of material concerns. We are interested in the situational forces that prompt some Latinos to express hostility toward Black individuals, and we think one of these forces is the marginal inclusion of people of color as Americans. Membership in this category is contentious for Latinos and Black people. Whereas Blacks view themselves as a more American minority than Latinos (Carter Reference Carter2019; Zou and Cheryan Reference Zou and Cheryan2017), Latinos see themselves as having a tenuous claim on this category, as evidenced by systemic discourse framing Latinos as “perpetual foreigners,” even though most Latinos are US-born (Lacayo Reference Lacayo2017). Thus, it is plausible that insecurity about being American will prompt some Latinos to derogate Black people (e.g., Noel, Wann, and Branscombe Reference Noel, Wann and Branscombe1995).

The psychology behind this effect is one where excluding others reinforces one’s inclusion in a higher-status group, such as Americans—especially if one is a marginal American, as Latinos are considered to be (Lacayo Reference Lacayo2017; Zou and Cheryan Reference Zou and Cheryan2017). As Pickett and Brewer (Reference Pickett, Brewer, Abrams, Hogg and Marques2005) teach us, the boundaries between an in-group and out-groups are crucial to marginal in-group members (Pickett, Bonner, and Coleman Reference Pickett, Bonner and Coleman2002; Pickett and Brewer Reference Pickett and Brewer2001). Their position as less prototypical members of an in-group threatens them with being confused with an out-group, which weakens their sense of belonging in a more desirable in-group. To bolster their inclusion in this in-group, marginals are motivated to clarify intergroup boundaries (Ellemers and Jetten Reference Ellemers and Jetten2013). Clearer boundaries enable marginals to preserve their peripheral position while distancing themselves from an out-group. This implies that Latinos might express prejudice toward Black people to maintain their loose inclusion as Americans while also differentiating themselves from Black individuals.Footnote 1

Our first hypothesis (H1), then, is that affirming Latinos’ fledgling status as American catalyzes them to denigrate Black individuals, which enables Latinos to reinforce their position as marginal Americans (Jetten et al. Reference Jetten, Branscombe, Spears and McKimmie2003; Noel, Wann, and Branscombe Reference Noel, Wann and Branscombe1995). People of color recognize their station in America’s racial order (Zou and Cheryan Reference Zou and Cheryan2017), which motivates them to make gains in their relatively lower rank, even if that means spurning interminority unity (Kim Reference Kim2003; Pérez and Kuo Reference Pérez, Crystal and Bianca2021). This aligns with system justification research (Jost, Banaji, and Nosek Reference Jost, Banaji and Nosek2004), which shows that instead of dealing with the uncertainty that comes with transforming a racial order, marginalized groups find it more reassuring to rationalize the mental discomfort caused by their oppression. Thus, when Latinos’ position as Americans is affirmed, they will express anti-Black racism to fortify this rank, with downstream reductions in support for pro-Black policies.

An alternative hypothesis (H2) is that Latino prejudice toward Black people is triggered by a downgraded position within the American category. This places (H2) in direct competition with (H1), which should clarify whether an upgraded versus downgraded position as marginal Americans more strongly catalyzes Latino’s anti-Black prejudice. As Soroka (Reference Soroka2014) and others (Kahneman and Tversky Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979) remind us, losses are more psychologically painful than gains, which means some Latinos might express greater prejudice when their marginal status as Americans is called out. This aligns with work on racial alienation (Bobo and Hutchings Reference Bobo and Hutchings1996; Hutchings et al. Reference Hutchings, Wong, Jackson, Brown, Charles, Gerken and Kang2011), which finds that people of color perceive other nonwhites as threats when they feel estranged from society. For example, theorists of segmented assimilation observe that Latinos are, on average, a lower-class population (Portes and Zhou Reference Portes and Zhou1993), which means they face dim prospects for socioeconomic mobility (Telles and Ortiz Reference Telles and Ortiz2008). According to some analysts (Portes and Rumbaut Reference Portes and Rumbaut2001a; Reference Portes and Rumbaut2001b), this places Latinos at risk of remaining in an underclass along with African Americans and other similarly disadvantaged groups. Thus, Latinos might reassert their marginal American status by voicing more prejudice, with greater opposition for pro-Black initiatives (H2). This meshes with work on how shared categories (American) can unify groups (e.g., whites, Latinos), but desensitize them to inequities between them (e.g., Blacks, Latinos; Banfield and Dovidio Reference Banfield and Dovidio2013; Dovidio, Gaertner, and Saguy Reference Dovidio, Gaertner and Saguy2015).

Our final hypotheses (H3 and H4) consider which Latinos are more likely to react to gains and losses in their marginal position as Americans by expressing anti-Black racism. We reason that liberal ideology plays an underappreciated role here. We see ideology as one useful gauge on the political heterogeneity of Latinos: America’s largest minority (Garcia Reference Garcia2012). Unlike partisan identity, where nontrivial shares of Latinos report being unaffiliated with a party (Hajnal and Lee Reference Hajnal and Lee2012), ideology captures a fuller range of political heterogeneity. This ideology is symbolic in nature (Ellis and Stimson Reference Ellis and Stimson2009), reflecting the various racial groups and movements associated with contemporary U.S. notions of liberals and conservatives, especially the intertwining of liberals with racial minorities and minority-centered movements (Alamillo Reference Alamillo2019).Footnote 2

Although Latinos’ ideological orientation generally drifts in a liberal direction, meaningful variance exists around this central tendency (García Reference Garcia2012), with an estimated 20% to 30% viewing themselves as conservative. Although Cuban-origin Latinos are known to self-identify as conservatives at higher levels than other Latinos (Garcia Reference Garcia2012), newer work shows that net of national-origin differences, conservative Latinos expressly deny that racism exists and support right-wing candidates (Alamillo Reference Alamillo2019; Hickel et al. Reference Hickel, Alamillo, Kassra A. R. and Collingwood2020). This implies that Latino liberals represent their ethnic group’s prototype, with Latino conservatives reflecting deviations from this average (Ellemers and Jetten Reference Ellemers and Jetten2013; Schmitt and Branscombe Reference Schmitt and Branscombe2001). This feature is critical because, under some conditions, liberal Latinos are more apt to identify with African Americans as people of color (Pérez Reference Pérez2021), suggesting an inclination to sometimes identify with Black peers.Footnote 3

In contrast, conservative Latinos are predisposed to think negatively of Black individuals and other people of color and to psychologically view themselves as distinct from them. Conservative Latinos are highly supportive of politics and candidates that are overtly hostile to African Americans and other minority groups (Hickel et al. Reference Hickel, Alamillo, Kassra A. R. and Collingwood2020). They are also inclined to deny the presence of racism and racist institutions (Alamillo Reference Alamillo2019). And, they are more likely to prioritize their American identity over their ethnic one (Hickel et al. Reference Hickel, Alamillo, Kassra A. R. and Collingwood2020). This implies that conservative Latinos might feel more secure in their position as Americans because they already construe their world in ways that maintain psychological distance from Black people.

This discussion yields two competing hypotheses: (H3) predicts that conservative Latinos are more responsive to questions about their position as Americans because they are predisposed to express anti-Black racism and resistance to racial diversity (Alamillo Reference Alamillo2019; Hickel et al. Reference Hickel, Alamillo, Kassra A. R. and Collingwood2020). Yet this disposition against race-related issues also means that shifts in Latinos’ rank as Americans might have difficulty increasing racism further among Latino conservatives, who already view themselves as distinct from Black individuals and other racial minorities. Thus, (H4) suggests it might be liberal Latinos who are more sensitive to their rank as American. Because liberal Latinos are psychologically closer to Black individuals, they should be more motivated to differentiate themselves from Black peers under situational pressures (Brewer Reference Brewer1991), such as reminders of their marginal rank as American. If true, this will align liberal Latinos with their conservative counterparts in terms of expressing greater racism toward Black people, with downstream reductions in support for pro-Black policies.

We report four studies that collectively test these hypotheses.Footnote 4 Study 1 uses American National Election Studies data to show that Latino adults who see themselves as more American express greater prejudice against Black people, which is then reliably associated with weaker support for affirmative action and federal aid to Black individuals. Studies 2 and 3 directly manipulate Latinos’ sense of being American. When Latinos feel they are being incorporated as Americans, they sometimes express slightly more racism toward Black people, which is associated with reduced support for pro-Black policies. Study 4 (preregistered) shows this process is substantially intensified if the initial spark is Latinos’ sense of status loss as Americans, which powerfully catalyzes anti-Black racism and vastly undercuts support for pro-Black policies. All these patterns are independent of economic factors and are generally stronger among Latino liberals than Latino conservatives. We discuss our results’ implications for further theory building and knowledge accumulation in the realm of U.S. interminority politics.

Study 1: Feeling More American Reduces Latino Support for Pro-Black Policies

Our theoretical argument distills into a mediation process, which allows us to test a proposed mechanism behind an effect. A mediation framework allows us to illuminate how Latinos’ sense of position as American leads them to oppose policies that target Black individuals. In a mediation analysis, a treatment variable (i.e., position as American) produces changes in an outcome (i.e., opposition to pro-Black policies) through an intervening variable or mediator (i.e., racial prejudice).

Per our theorizing, our most basic expectation is that Latinos’ marginal position as Americans influences their expressions of prejudice toward Black people, which has downstream consequences for their support of pro-Black policies (H1 and H2). We yield initial support for this proposed mechanism by studying Latino adults who participated in the 2012 (n = 1,009) American National Election Studies (ANES), which fielded measures of American identity, racial resentment, and several policy proposals focused on Black communities. These data enable us to operationalize all variables stipulated by our mediation process, which we explain below.

Study 1 (2012 ANES): Measures

In our framework, our treatment variable is one’s sense of position as Americans (Devos and Banaji Reference Devos and Banaji2005; Theiss-Morse Reference Theiss-Morse2009). We conceptualize this positionality as driving expressions of prejudice, consistent with prior work on in-group processes and individual attitudes and behavior (Ellemers and Jetten Reference Ellemers and Jetten2013). Although the ANES does not contain a measure of one’s sense of position within the category, American, it does contain an item capturing the centrality of being American to oneself (cf. Leach et al. Reference Leach2008), which we treat as a proxy here. To this end, we use a single item asking respondents “How important is being American to your identity?” answered on a scale from 1 extremely important to 5 not at all important. We recode the responses so that higher values reflect greater identity importance.

We construe prejudice toward Black people as a mediator of Latinos’ political views about African Americans, which we measure with an extensively validated scale of racial resentment (Kinder and Sears Reference Kinder and Sears1981; Tarman and Sears Reference Tarman and Sears2005). This index consists of four statements about African Americans, answered on scales from 1 agree strongly to 5 disagree strongly, including “Irish, Italians, Jewish, and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same without any special favors.” See Section 1 in the Supplementary Materials (SM.1) for item wordings. We code replies so that higher values reflect more prejudice.

Finally, our outcomes are support for (1) affirmative action toward African Americans, (2) fair treatment of Black people in jobs, and (3) federal aid to Black individuals. We tap opinions about affirmative action with an item on a scale from 1 strongly favor to 5 strongly oppose, one of which asked, “Do you favor, oppose, or neither favor nor oppose allowing universities to increase the number of [B]lack students studying at their schools by considering race along with other factors when choosing students?” We tap opinions about fair treatment of Black individuals in the workplace with the item “Should the government in Washington see to it that [B]lack people get fair treatment in jobs or is this not the federal government’s business?” answered on a scale from 1 government should see to fair treatment of Blacks to 5 fair treatment is not the government’s business. Finally, we gauge support for federal aid to Black people with the item “Where would you place yourself on this scale, or haven’t you thought much about this?” with replies arrayed from 1 government should help Blacks to 7 Blacks should help themselves. We code all outcomes so that higher values reflect more support.

Our analyses control for several covariates, including ideology, nativity, and ethnic identity. We report these complete results in SM.2. To better ensure our proposed mechanism is independent of Latinos’ economic concerns (cf. McClain and Karnig Reference McClain and Karnig1990; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2015), we also control for financial worry, income, and education. The essential paths to finding evidence here are (1) the relationship between American identity and racial resentment and (2) between racial resentment and our suite of outcomes (cf. Hayes Reference Hayes2021; Zhao, Lynch, and Chen Reference Zhao, Lynch and Chen2010). To facilitate our results’ interpretation, we focus on our primary variables and report other covariates in SM.2. All variables are rescaled to a 0–1 range, thus reflecting percentage-point shifts in a construct. Finally, we note that this survey occurred during 2012, which lets us observe a connection between American identity and racial resentment among Latinos before the nationalist and racially hostile administration of former president, Donald Trump (Lajevardi and Abrajano Reference Lajevardi and Abrajano2019; Mason, Wronski, and Kane Reference Mason, Wronski and Kane2021).Footnote 5

Study 1’s Results

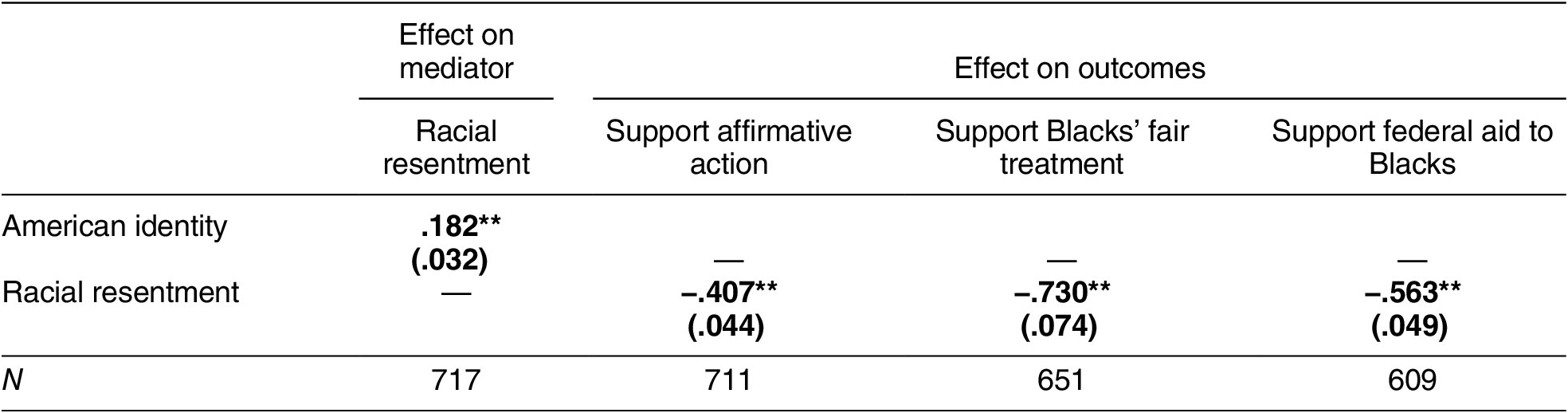

Does one’s position as American motivate Latinos to express anti-Black racism in a politically consequential way? Table 1 suggests that it does. The coefficients there indicate that a unit shift in American identity reliably boosts Latino prejudice toward Black people (.182, p < .001, two-tailed), an effect representing an increase of nearly 20% of the range of our racial resentment scale. This implies that Latinos who construe themselves as more American express stronger racial resentment toward Black people.

Table 1. Racial Resentment Mediates the Effect of American ID on Latino Support for Black-Centered Policies (2012 ANES)

Note: Entries are ordinary least squares (OLS) coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. All variables range continuously from 0 to 1. Additional covariates are not shown. Complete results reported in Table SM.2 in the Supplementary Materials. **p < .05 or better, *p < .10 or better, two-tailed.

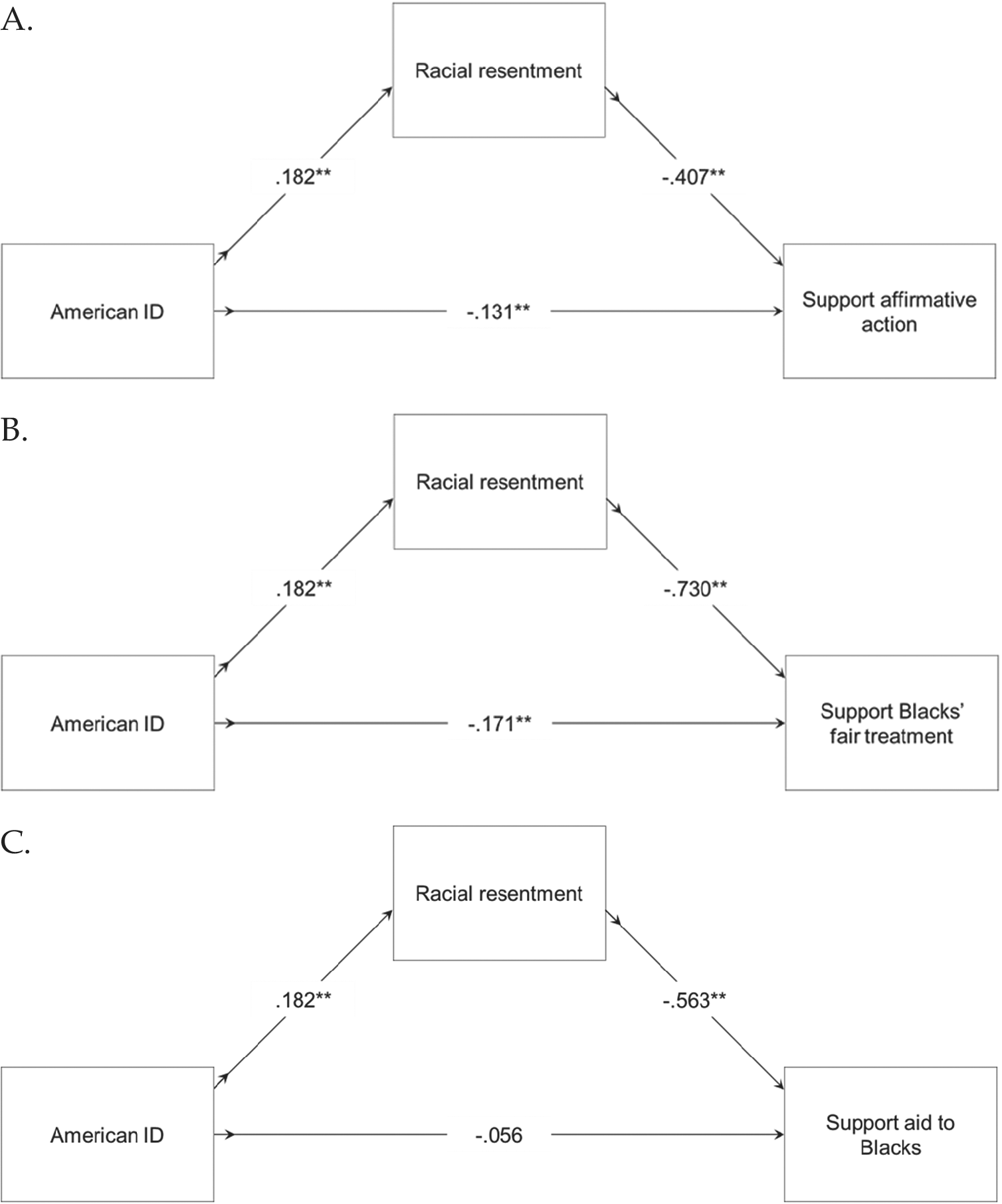

This prejudice appears to be politically influential, as heightened resentment levels are reliably associated with weaker Latino support for affirmative action toward Black individuals (-.407, p < .001, two-tailed), federal guarantee of Black people’s fair treatment in jobs (-.730, p < .001, two-tailed), and federal aid to African Americans (-.563, p < .001, two-tailed). These decreases in support are substantial, for they range from about 40% to nearly 75% of the range of our outcomes. Further analyses suggest this association between racial resentment and American identity in this sample is unmoderated by liberal ideology in a substantive or statistical sense (-.002, p < .947), with complete results reported in SM.3. Figure 1 depicts the mediation process indicated by these results.

Figure 1. Racial Resentment Motivates Opposition to Black-Centered Policies among Latino and Adults Who Self-Identify More Strongly as American (2012 ANES)

Note: These path diagrams depict the indirect of effect of being American on opposition to pro-Black policies. The respective coefficients are from the models reported in Table 1.

Summary and Implications: Study 1

Drawing on the 2012 ANES Latino oversample, we find correlational evidence supporting our claim that a sense of position as American is associated with greater prejudice among Latinos, which then significantly undercuts their support for Black-centered policies. As we show in SM.2, this basic pattern also emerges in the 2016 ANES, which yielded a substantially smaller sample of Latinos.

Still, we failed to detect any evidence that Latinos’ ideological orientation moderates the link between one’s position as American and prejudice toward Black people. This might simply be due to weak control over Latinos’ position as Americans, as we employed a proxy rather than a direct measure of this variable. Moreover, although we find that sense of position as American influences expressions of racial resentment among Latinos, we cannot rule out that the obverse is true—namely, that expressions of prejudice bolster one’s sense of positionality as American. We address these limitations by manipulating Latinos’ sense that they are fledgling Americans. This allows fuller control over the ordering of positionality as American in our framework while providing a new opportunity to observe the fuller chain reaction we anticipate.

Studies 2 and 3: Does Fledgling Status as American Increase Liberal Latinos’ Racism?

Here we analyze two experiments, conducted on the online platform Prolific, which manipulated Latinos’ sense of positionality as Americans (IRB #20-20224). Study 2 (2020) sampled N = 248 Mexican Latinos in the US, and Study 3 (2020) sampled N = 330 Latinos of all national origins. Both opt-in samples were yielded nonprobabilistically, yet they still display rich heterogeneity in terms of basic demographics, such as age and gender (see SM.5). In both studies, Latino adults from Prolific’s panel were invited to participate in our eight-minute survey in exchange for $1.60 (a rate recommended by Prolific). After consenting to participate, individuals were randomly assigned to a control group with no information or a condition manipulating Latinos’ position as Americans. This treatment was a mock news article titled “New Census Data Reveal Latinos are Becoming an Important Part of U.S. Society.” As detailed in SM.5, this news brief highlights Latinos making gains in education, politics, and private industry, which suggest “Latinos are becoming fuller members of U.S. society.” Posttreatment, participants answered items gauging racial resentment. Participants then completed the same outcomes as in Study 1, plus items gauging support for #BlackLivesMatter and harsher penalties for hate crimes against Blacks. We combine these into a reliable index (Study 2, α = .800, Study 3, α =.817) where higher values indicate more support for pro-Black policies. All variables are rescaled to a 0–1 range. All participants were debriefed and given the opportunity to recall their data without penalty if they so wished.

Studies 2 and 3: Results

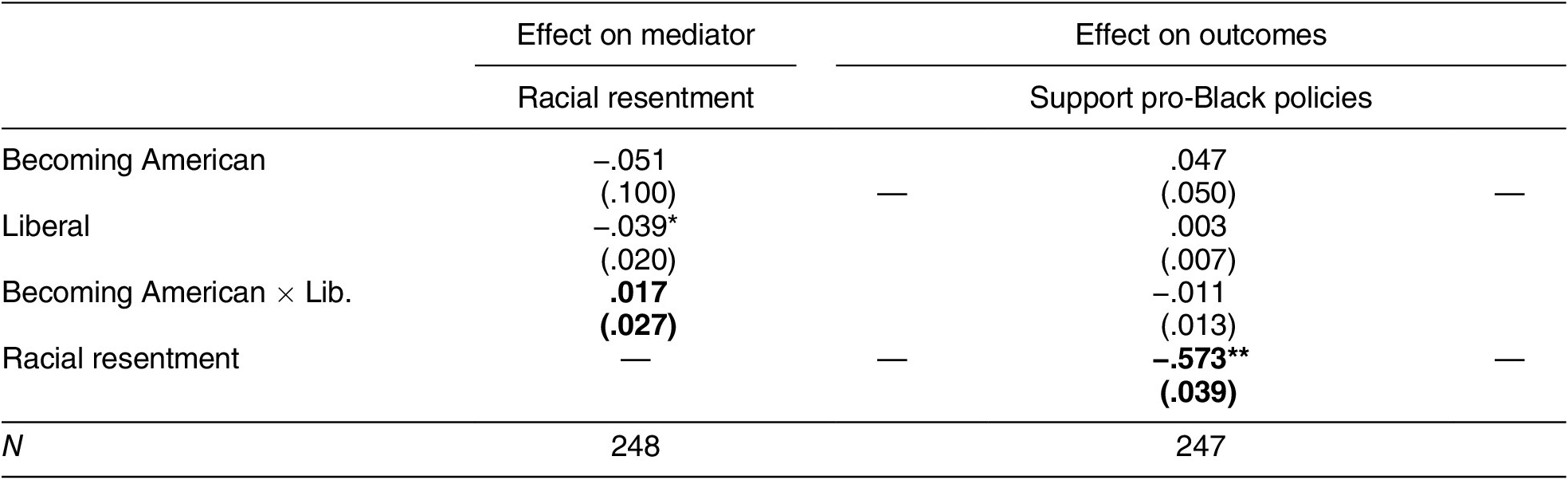

Table 2 details the results from Study 2, which sampled Mexican Latinos. There we see some evidence aligning with our theoretic reasoning. First, notice that in absence of any information (control group), liberal ideology is negatively and reliably associated with Latino levels of racial resentment, suggesting that, at baseline, these types of individuals express lower levels of racism toward African Americans. This situation appears to change in light of our treatment, which highlights Latinos’ improving status as Americans. Among conservative Latinos, our treatment produces a small and insignificant decrease in their racial resentment levels (-.051, p < .597, two-tailed). However, among liberal Latinos, the interaction between our treatment and their ideological orientation suggests it is liberal Latinos who are slightly more reactive to this sense of location relative to their conservative counterparts (.017, p < .535, two-tailed). Although this positive effect is tiny (about a 2-percentage-point increase) and statistically unreliable, its direction implies that liberal Latinos express a relatively higher level of prejudice than their conservative counterparts (-.051 + .017 = -.034, ns). In turn, this slight nudge toward greater racial resentment steers all Latinos away from supporting pro-Black policies, a pattern that is statistically and substantively meaningful (-.573, p < .001, two-tailed), reflecting a decrease of 57 percentage points.

Table 2. Racial Resentment Mediates the Effect of “Becoming More American” on Latino Support for Black-Centered Policies (Study 2, 2020)

Note: Prolific sample. Entries are OLS coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. All variables range from 0 to 1. **p < .05 or better, *p < .10 or better, two-tailed.

Table 3 details the results from Study 3, our second experiment (all Latinos). Again, we find that at baseline, liberal ideology is negatively associated with levels of racial resentment among Latinos. In light of our treatment, however, we observe evidence that is directionally consistent with our reasoning and statistically reliable. In particular, exposure to information that Latinos’ position as American is improving leads liberal Latinos to express reliably more racial resentment (.217, p < .001, two-tailed) than their conservative counterparts (-.149, p < .017, two-tailed), which yields a reliable increase in prejudice among liberal Latinos (-.149 + .217 = .068, SE = .025, p < .006, two-tailed). In turn, this significant boost in prejudice significantly undercuts Latino support for pro-Black policies by about 57 percentage points (-.570, p < .001, two-tailed).

Table 3. Racial Resentment Mediates the Effect of “Becoming More American” on Latino Support for Black-Centered Policies (Study 3, 2020)

Note: Prolific sample. Entries are OLS coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. All variables range from 0 to 1. **p < .05 or better, *p < .10 or better, two-tailed.

The evidence in this pair of experiments roughly fits with the claim that Latinos’ racism toward Black individuals is sensitive to their position as marginal Americans—which then reduces support for pro-Black initiatives. To bolster our confidence in this inference, we conducted a mini meta-analysis (Goh Reference Goh2016), which lets us assess whether, holding constant each study’s unique features (e.g., sample composition and size), sharper statistical evidence emerges by pooling across both experiments.

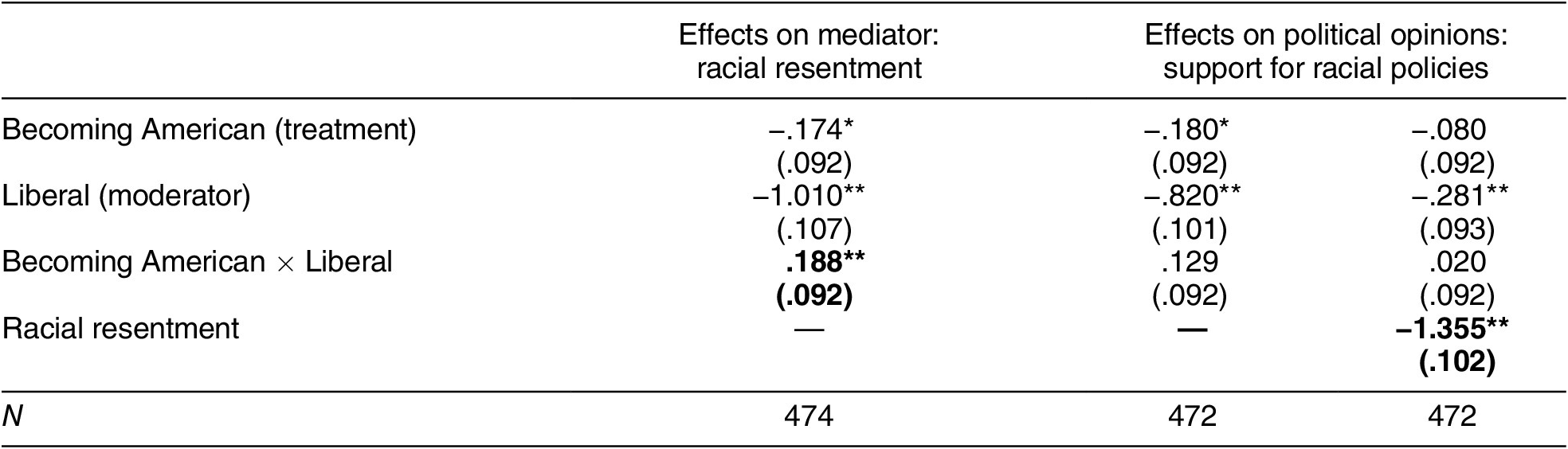

Table 4 contains the relevant results, with entries scaled as d values, which underscore effect size (d values around .20, .50, or .80 and greater are deemed small, medium, and large, respectively). There we see a strong and reliable negative association (d = -1.010) between liberal ideology and racial resentment among Latinos at baseline. We also see that with gains in statistical power via this meta-analysis, Latino liberals express reliably more racial resentment (d = 0.188, p < .042, two-tailed). That is, Latinos who are induced to feel more American increase their expression of prejudice toward Black individuals: a measurable effect that is statistically significant at the 5% level. This higher level of racism is then significantly associated with reductions in Latino support for pro-Black initiatives (d = -1.355, p < .001, two-tailed). Based on this mini meta-analysis, we provisionally conclude that a sense of improved position as Americans leads liberal Latinos to express greater prejudice, which is then associated with reductions in their support for pro-Black policies.Footnote 6

Table 4. Mini Meta-Analyses of Studies 3 and 4: Racial Resentment Mediates the Effect of “Becoming More American” on Support for Black-Centered Policies

Note: Entries are d values generated from raw OLS coefficients. Values (d) around .20, .50, and .80 are considered small, medium, and large, respectively. **p < .05 or better, *p < .10 or better, two-tailed.

Studies 2 and 3: Summary and Implications

Across two experiments, we find mixed support for the claim that, in light of an improved position as American, Latino liberals express greater prejudice toward Black people, which then undermines Latino support for Black-centered policies. Indeed, it is only in our meta-analysis that we find clearer support for this contention. Nonetheless, a major lesson from our analysis is the moderating role of ideology. In essence, our treatment here (Table 4) appears to bring liberal Latinos (.188) in line with conservative Latinos (-.174) in terms of their racial resentment levels. This “equalizing” pattern then results in racial resentment steering all Latinos in our samples (regardless of ideology) to express more opposition to Black-centered policies. Building on these insights, our next study probes whether a decline in one’s status as American more acutely triggers our anticipated chain reaction among Latinos.

Study 4: Does a Downgraded Status as American Drive Latinos to Express Racism?

Building on our accumulated findings from Studies 1–3, Study 4 (2021) examines the triggers of Latino racism toward African Americans by focusing on a downgrading of Latinos’ status as peripheral Americans (IRB #20-20224-AM-00001). The theoretic assumption we make here is that losses—in this case, slippage in Latinos’ tenuous status as Americans—are more distressing than gains. Thus, to recover from this downgraded position, Latinos will express greater racism toward Black people, with liberal Latinos being particularly sensitive to this unsettled state, given their closer political proximity to Black people. We also consider whether it is simply a status downshift that spurs this reaction or whether a direct comparison to Black people, the relevant out-group here, is required for this chain reaction to be triggered among Latinos (cf. Tajfel Reference Tajfel1981; Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979). The use of a direct comparison to Black people aligns with our assumption that the sharpening of intergroup boundaries allows marginal Americans, like Latinos, to bolster their belonging in that group by excluding Black individuals (Pickett and Brewer Reference Pickett, Brewer, Abrams, Hogg and Marques2005).

To these ends, we designed a preregistered experiment with Latino adults (N = 1,200), which we undertook through Dynata, an online survey platform (for anonymous preregistration, see SM.6). Participants in this study were recruited with census benchmarks in mind for age, education, and gender for Latinos in order to yield a highly heterogeneous sample. As detailed in SM.6, we preregistered two confirmatory hypotheses. The confirmatory predictions were (H2a): downgrading Latinos’ status as Americans increases their racial resentment, with downstream associations with greater opposition to Black-centered policies, and (H2b) the downgrading of Latinos’ status as Americans by comparing them to Black people is the trigger to greater racial resentment, with downstream associations with greater opposition to Black-centered policies. In addition, we preregistered an exploratory analysis of ideology as a moderator of these treatments, in light of the results from Studies 2 and 3. As we detail below, we confirm H2b and observe that liberal Latinos are especially sensitive to the treatment that downgrades their American status by comparing them to their Black peers.

Eligible Latinos from Dynata’s panel were invited to participate in Study 4 in exchange for points through Dynata’s internal panelist reward system. After consenting, Latino participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: a control group with no information or one of two treatment conditions. In both treatment conditions, participants read a news brief attributed to the Associated Press (AP), which was titled “Latest Census Shows Latinos Losing Foothold in U.S. Society; Status as Newest Americans More Uncertain Now [Similar to Blacks]. As detailed in SM.6, both briefs highlight declines in the gains Latinos had made as Americans (e.g., poor educational performance, lack of medical insurance). The only difference between both treatments is whether a direct comparison to Black people is made, as captured by the brackets in the preceding title.

Posttreatment, participants answered four racial resentment items, with two of them revised to further increase their relevance to Latinos (see SM.7). Specifically, the two racial resentment items that compare African Americans to whites (i.e., “no special favors,” “work harder”) were modified to compare Black people to Latinos. For example, the “no special favors” item was rephrased to say “Mexicans, Salvadorans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and other Latinos have worked their way up to earn what they have. Blacks should do the same without any special favors” (α = .757). We did this for two reasons. First, although the original racial resentment scale was developed with white individuals in mind, our focus is on U.S. Latinos. Therefore, some of the unevenness in racial resentment’s performance among Latinos in Studies 1–3 might be due to this “gap” between the phrasing of the racial resentment items and the (Latino) respondents who complete them. Second, a close reading of our argument implies that Latinos’ embrace of their marginal position as American entails a comparison with—and exclusion of—an out-group (i.e., Black people; Pickett and Brewer Reference Pickett, Brewer, Abrams, Hogg and Marques2005). Our revised resentment items sharpen this comparison, which further aligns our mediator with our treatments in this study. This will let us observe the extent to which an invidious comparison between Latino and Black individuals as Americans drives the mediated reaction we anticipate.

Following our racial resentment items, participants answered five policy proposals centered on African Americans, similar to those previously analyzed (see SM.6), including a new one that probed support for “Ensuring that more Black candidates are elected to Congress to represent Blacks and other people of color” (α = .899). All variables range from 0 to 1, with higher values reflecting greater quantities. Once again, all participants were formally debriefed after the study and given the opportunity to recall their data without penalty, if they so wished.

Study 4: Results

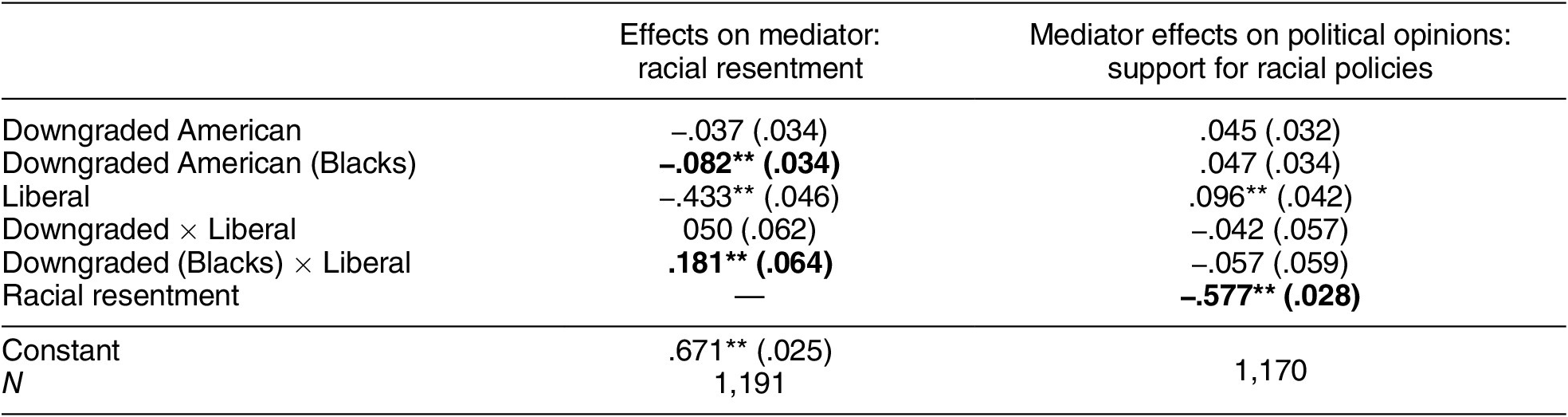

Table 5 reports the results of our analysis. There we see, once again, that in the absence of any information, higher levels of liberal ideology are negatively associated with racial resentment (-.433, p < .001, two-tailed) among Latinos, a unit shift that reflects a decrease in prejudice of about 43 percentage points. However, this baseline pattern changes in light of exposure to our treatments, which underline a declining marginal status as Americans among Latinos. Notice, first, that undermining Latinos marginal status as Americans, without any explicit comparison to Black people, does not have a reliable effect on its own or among liberal Latinos. Indeed, although the interaction between this treatment and liberal ideology is correctly signed, the effect is small and statistically insignificant (.050, p < .418, two-tailed). We note that this weak effect emerges despite the fact that our racial resentment measure is arguably closer in relevance to our Latino participants, as two of the items center on them specifically.

Table 5. “Downgraded” American Status Triggers Racial Resentment among Liberal Latinos When Comparison with Blacks is Salient (Study 4, 2021)

Note: Entries are OLS coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses. All variables range from 0 to 1. **p < .05 or better, *p < .10 or better, two-tailed.

The stronger catalyst to Latinos’ prejudice toward African Americans appears to be the undermining of their marginal American status, coupled with a direct comparison to Black individuals. This particular treatment crisply triggers the reaction among liberal Latinos that is anticipated by part of our framework. More specifically, calling attention to Latinos’ falling status as American and explicitly comparing their new position to that of Black individuals leads liberal Latinos to express reliably more racism toward African Americans—an 18-percentage-point increase, to be exact (.181, p < .005, two-tailed). This appears to bring liberal Latinos closer in line with the racial resentment levels held by their more conservative coethnics, which then steers all Latinos away from supporting pro-Black policies (-.577, p < .001, two-tailed). Critically, this pattern is robust to the inclusion of income differences as a covariate, which we use to account for economic concerns that Latinos may sense from their Black peers.Footnote 7

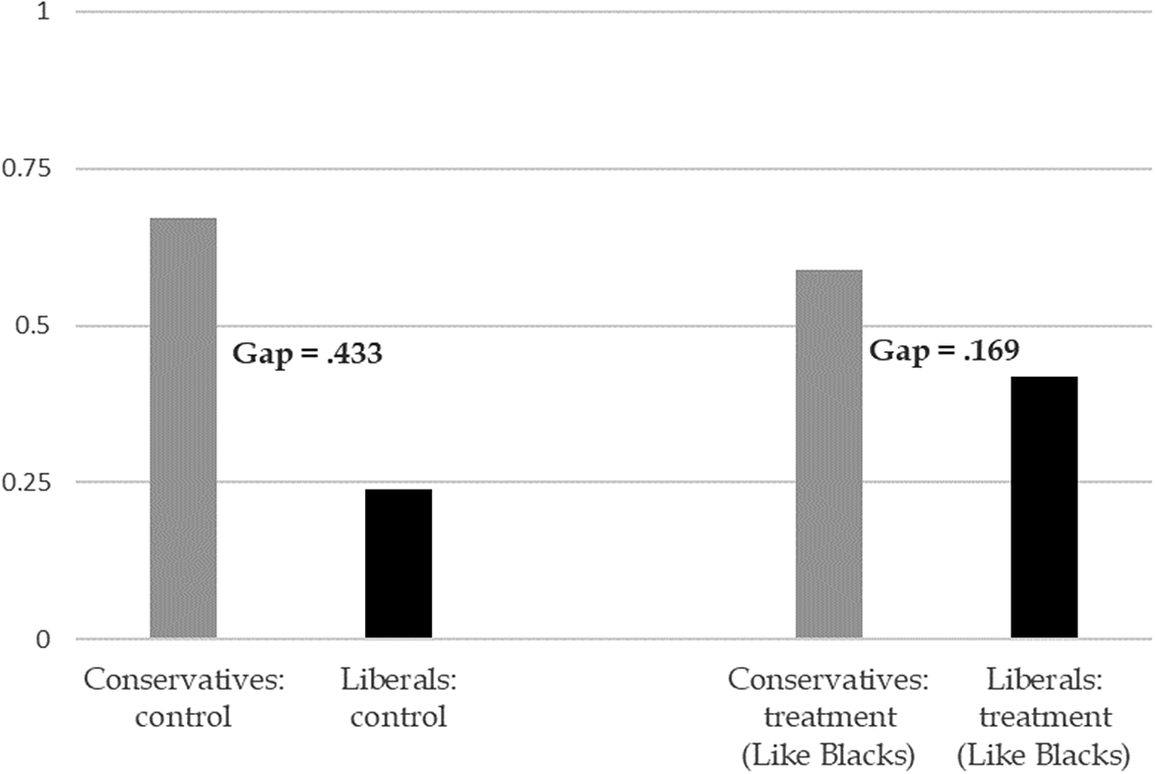

Figure 2 depicts the interaction between our treatment, Downgraded American Blacks, and liberal ideology. We created this graph using the raw coefficients in Table 5. Because our other treatment (i.e., Downgraded American) displays insignificant effects on its own or moderated by ideology, Figure 2 focuses on the quantities that are statistically reliable, which further facilitates the interpretation of our primary results. Figure 2 indicates that among conservative Latinos in the control group, the level of racial resentment is .671, a high level that is provided by our constant and is consistent with prior work (e.g., Alamillo Reference Alamillo2019). In turn, the level of racial resentment among liberal Latinos in the control group is substantially lower .238 (.671 − .433 = .238), which produces a gap in racial resentment between conservative and liberal Latinos that is about 43 percentage points (.671 − .238 = .433).

Figure 2. The Effect of Downgraded American Status (Like Blacks) on Racial Resentment by Latino Ideology

Note: This figure depicts the reduction in the observed racial resentment gap between conservative versus liberal Latinos as a consequence of a treatment. These quantities are calculated in text using the coefficients in Table 5 under the column “racial resentment.”

This difference in racial resentment narrows in the treatment condition where Latinos’ degraded status as Americans is compared to that of Black people. Here, the level of racial resentment among conservative Latinos registers at about .589 (.671 − .082 = .589), whereas among liberal Latinos it comes in at about .419 (.671 − .433 + .181 = .419), thus producing a smaller gap of about 17 percentage points (.589 − .419 = .17). This aligns with our interpretation that liberal Latinos become more racially resentful in light of this treatment, which reduces the gap in prejudice between them and their conservative counterparts. In turn, an increase in racial resentment then steers all Latinos toward substantially weaker support for policy initiatives targeting African Americans.Footnote 8

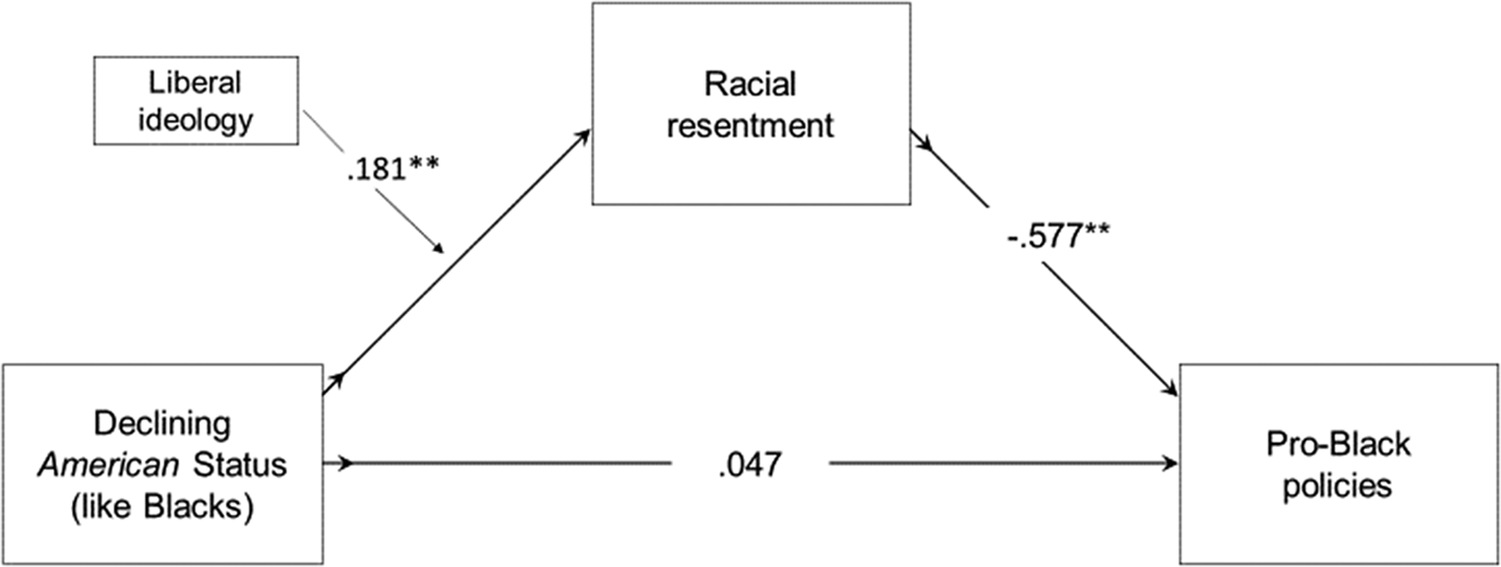

Figure 3 depicts this full chain reaction anticipated by our theoretical framework. Specifically, Figure 3 shows that highlighting Latinos’ downgraded status as marginal Americans, while comparing them to Black people, boosts racial resentment among Latino liberals by about 18 percentage points (.181, p < .005, two-tailed), which undermines the support they are predisposed to provide for pro-Black policies in the absence of any status threat. In turn, this heightened prejudice level among liberal Latinos brings them more in line with their conservative counterparts, which then steers all Latinos away from supporting policies that target and benefit their African American peers (-.577, p < .001, two-tailed) by nearly 58 percentage points.

Figure 3. Downgraded American Status Heightens Prejudice among Latino Liberals, Which Then Undercuts Latino Support for Pro-Black Policies

Note: This path diagram depicts the moderated indirect of effect of being American on opposition to pro-Black policies. The respective coefficients are from the interactive models reported in Table 5.

Sensitivity Analysis

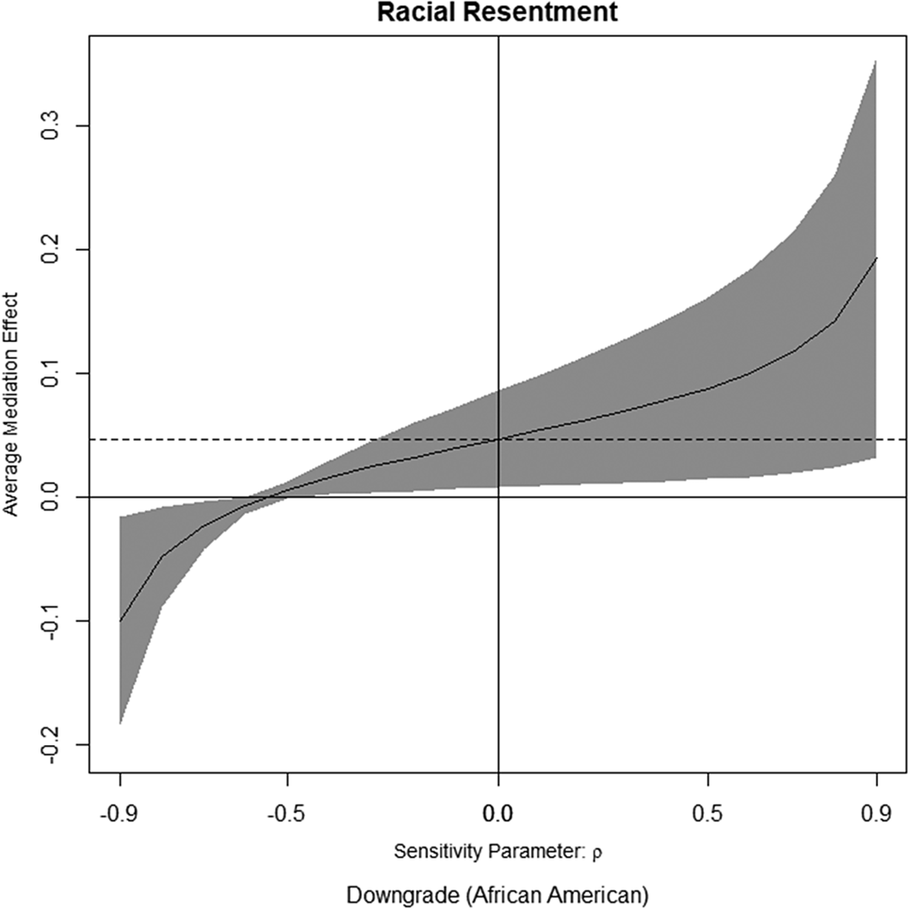

Although mediation analyses are incredibly important in helping to establish possible mechanisms behind experimental effects (Igartua and Hayes Reference Hayes2021; Spencer, Zanna, and Fong Reference Spencer, Zanna and Fong2005), challenges arise when a mediator (i.e., racial resentment) is measured rather than manipulated (Bullock and Green Reference Bullock and Green2021; Bullock, Green, and Ha Reference Bullock, Green and Ha2010; Imai and Yammamoto Reference Imai and Yamamoto2013). We undertook this approach because increases in racial prejudice are incredibly difficult and unethical to randomly assign (Igartua and Hayes Reference Hayes2021; Spencer, Zanna, and Fong Reference Spencer, Zanna and Fong2005). In a situation like this one, a measured mediation approach like ours is more appropriate, but with one caveat (Hayes and Igartua Reference Igartua and Hayes2021; Spence, Zanna, and Fong Reference Spencer, Zanna and Fong2005). Because our mediator is measured, rather than manipulated, it is vulnerable to confounding (Bullock and Green Reference Bullock and Green2021; Bullock, Green, and Ha Reference Bullock, Green and Ha2010; Imai and Yamamoto Reference Imai and Yamamoto2013). Like many other statistical tools, mediation analyses can be compromised by the effects of unobserved pretreatment variables, which we mitigate here by conducting a sensitivity analysis (Imai and Yamamoto Reference Imai and Yamamoto2013). This helps us quantify the robustness of our mediation result.

Following the advice of Imai and Yamamoto (Reference Imai and Yamamoto2013), we estimate how large the error correlation (ρ, rho) between our mediator and an unmodeled confounder must be in order for our indirect effect to be compromised. As Figure 4 indicates, our mediation effect (dashed line) is quite robust to an omitted confounder, such that an error correlation of ρ (rho) = ≤ -.60 would have to emerge for the effect of our mediator (racial resentment) to vanish to zero or to switch signs. This helps to increase confidence in the robustness of Study 4’s results. We return to this point in the conclusion of the paper when we discuss the implications of our results for future research.

Figure 4. Sensitivity of Observed Mediation Effect with Respect to Error Correlation between Racial Resentment and an Omitted Confounder

Note: This figure depicts the correlation (ρ) between errors in an omitted confounder and our mediator (racial resentment) where our mediation effect vanishes to zero. We estimated (ρ) via medsens() in the R package, mediation. The estimated (ρ) is based on 1,000 simulations.

Study 4: Summary and Implications

This study tested whether Latinos respond to their marginal position as Americans by derogating Black individuals. We find that they do. Specifically, we discovered that it is politically liberal Latinos who most react to this downward shift in their position as Americans. Indeed, priming a sense of lost position as marginal Americans led liberal Latinos to express greater racial resentment, which is then strongly associated with reduced support for pro-Black policies. This effect was sharpest when Latinos were expressly compared to Black individuals, which is consistent with the distinctiveness motive we outlined in our theoretic discussion (Pickett and Brewer Reference Pickett, Brewer, Abrams, Hogg and Marques2005). In the next section, we discuss these results in light of our four studies. In particular, we explain which aspects of our theoretic argument are empirically supported and what implications this has for research on interminority politics in the United States.

Conclusions and Implications

Back in 2000, as political scientists again debated the origins and consequences of race and racism in America (Sears, Sidanius, and Bobo Reference Sears, Sidanius and Bobo2000), the renowned political scientist, Michael Dawson, astutely observed that although racial and ethnic groups in the U.S. are clearly ordered in a descending hierarchy of status, privilege, and power, this “American racial order is a phenomenon with which many researchers are loathe to deal” (Reference Dawson, Sears, Sidanius and Bobo2000, 344). This aversion is especially strong when the role of people of color in bolstering this hierarchy is concerned (e.g., Jost, Banaji, and Nosek Reference Jost, Banaji and Nosek2004; Zou and Cheryan Reference Zou and Cheryan2017). Mindful of Dawson’s critique, we developed a theoretic argument that clarifies when and why Latinos denigrate African Americans—an effort meant to isolate some conditions under which prejudice compromises interminority solidarity (Craig and Richeson Reference Craig and Richeson2018; Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2003; Pérez and Kuo Reference Pérez, Crystal and Bianca2021). Accordingly, our framework pinpoints one situational trigger and one predisposing factor. In terms of the former, we reasoned that members of a stigmatized group are sensitive to their marginal membership in a high-status category, such as American. The uncertainty we addressed here is whether it is gains or losses in one’s position within this group that drives Latinos to lash out at Black individuals. In terms of the predisposing factor, we considered whether Latinos’ ideological orientation conditioned sensitivity to one’s position in a higher-status group.

Across four separate studies, all focused on Latino–Black relations, we found converging evidence in favor of one interpretation yielded by our theoretic framework. This is the idea that Latinos, a stigmatized ethnic group, are highly sensitive to downshifts in their position as marginal Americans, as losses are more psychologically painful than gains. Indeed, although we found some evidence that gains in American status can prompt a reaction among Latinos, it is the former which packed a more potent punch, especially when Latinos’ status was compared explicitly to that of African Americans.

We also found evidence that it is not all Latinos who react this way. Rather, it is liberal Latinos—the individuals who are politically most similar to their African American counterparts. This pattern was one of two outlined by our framework. We theorized that conservative Latinos already believe and endorse the negative views and feelings manifesting in prejudice toward Black people. As a result, it is harder for conservative Latinos to become even more hostile toward African Americans. In turn, although liberal Latinos generally express less prejudice than their conservative peers, they also have wider berth to become that way. We are left, then, with a basic insight we did not have before. Namely, in light of insecure status as American, liberal Latinos become more racially resentful toward Blacks, thus narrowing the gap in expressed prejudice between conservative and liberal Latinos. Subsequently, this increase in racial resentment drives all Latinos to express substantially weaker support for a variety of pro-Black policies.

We believe these findings are important for scholarly understandings of America’s racial hierarchy and the role it plays in undermining interminority cooperation (Carter and Pérez Reference Carter and Pérez2016; Masuoka and Junn Reference Masuoka and Junn2013; Zou and Cheryan Reference Zou and Cheryan2017). In the case of Black–Latino relations, accumulating work teaches us that effective coalitions between these groups are grounded in, and sustained by, a clear sense of commonality between these groups (Benjamin Reference Benjamin2017; Cortland et al. Reference Cortland2017; Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2003; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2015). In fact, recent scholarship teaches us that under some political circumstances, individuals from these distinct groups view themselves, collectively, as part of the same identity-based group—as people of color (Pérez Reference Pérez2021). However, such cohesiveness between minorities is not a constant in U.S. politics. Alas, our paper isolates one important circumstance when perceived similarity between Latinos and African Americans can generate invidious comparisons that undermine interminority coalition building (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979).

How generalizable are these results to other contexts and other groups? It depends on what one wishes to explain. Our argument rests on three main components: insecurities about group membership (i.e., American), invidious comparisons between minority groups (Latinos and Blacks), and a drive to (re)gain one’s position within a higher-status category (i.e., American) to positively differentiate oneself from similar “others” (i.e., African Americans). To extend this basic framework to additional groups and contexts, one needs to have a deep appreciation for the precise configuration of intergroup relations in a setting and a clear sense of which categories racial minorities feel insecure in. Consider other minority groups here in the U.S. Given Asian Americans’ subordination as a group that is “insufficiently American” but higher-status as a “model minority,” they might also feel insecure about being American, especially because foreign-born individuals are more prevalent among Asian Americans than among Latinos. However, prior work suggests Asian Americans are likely more sensitive to questions about their “model minority” status, which pegs them closer to whites (Zou and Cheryan Reference Zou and Cheryan2017). Thus, jeopardizing this relative positioning might lead Asian Americans to lash out at an “inferior” group like African Americans or Latinos. Of course, this is an empirical question that can be directly appraised. Our larger point here is that extending our framework beyond U.S. Latino–Black relations requires a deep appreciation for the particulars of a given interminority context.

Beyond questions of generalizability, we believe our evidence also encourages scholars to broaden their view about the roots of interminority conflict by paying even closer attention to the role of status-based considerations, which are structured by the very configuration of America’s racial order. In explaining interminority conflict, some scholars rightfully point to the role of competition over material resources, such as jobs, housing, and schools (e.g., McClain Reference McClain1993; McClain and Karnig Reference McClain and Karnig1990; McClain et al. Reference McClain, Lyle, Carter, Soto, Lackey, Cotton, Nunnally, Scotto, Grynaviski and Kendrick2007). This perspective implies that if competition over finite resources sparks interminority conflict, introducing more of these tangible resources should mitigate intergroup tensions. In contrast, our findings suggest that independent of economic factors, any sense of solidarity between minority groups can be split asunder by status-based concerns that are steeped in perceptions about the position of one’s group relative to that of others (cf. Bobo and Hutchings Reference Bobo and Hutchings1996; Carter Reference Carter2019; Masuoka and Junn Reference Masuoka and Junn2013; Sidanius and Pratto Reference Sidanius and Pratto1999). Although perceptions can also be corrected and leveled out, the pathways to do so are not always direct or obvious, which lends itself to more protracted—and sometimes intractable—conflict between minority groups (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985; Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979).

To gain a deeper appreciation for this implication, consider political relations between African Americans and Latinos. Both groups are generally progressive in their politics, with liberal Latinos and Black people inhabiting the same Democratic party (Abrajano and Alvarez Reference Abrajano and Alvarez2010; White and Laird Reference White and Laird2020). Yet under the “right” conditions, our work suggests this perceived similarity can lead some members of these groups to feel “too close for comfort,” thus motivating them to distinguish themselves from one another, with intraparty unity compromised as a result. In fact, this motivation to differentiate oneself from a proximate in-group might manifest in other ways besides prejudice, including reports of lighter skin tone among Latinos (Ostfeld and Yadon Reference Ostfeld and Yadon2022). Although this does not mean the Democratic coalition is doomed to fail, it does highlight how challenging it can be to produce and sustain interminority unity in some political contexts.Footnote 9

Our project also sheds new light on the incorporation of immigrant-based minorities, like Latinos, into America’s cultural mainstream. Sociologists and historians teach us that during previous waves of immigration, foreign-born individuals and their descendants gradually entered mainstream life due to gains in occupation, residence, and prestige (Roediger Reference Roediger2006). However, by boring down into the psychology of interminority relations, our work suggests that this transition is also marked by fits and starts, as groups continuously scan their field of race relations (Kim Reference Kim1999; Portes and Zou Reference Portes and Zhou1993) and work to navigate its crosscurrents. This is a crucial insight because it highlights the role of group agency in choosing (not) to build alliances with similarly situated groups in the complex terrain generated by America’s racial order. This is not to say this agency is unfettered, for it is strongly conditioned by one’s position in America’s stratification of racial populations. But it is to say that the gradual incorporation of a group like Latinos is not strictly an inevitable consequence of macro-level forces (e.g., the economy), but also the byproduct of individual choices over how to best position one’s in-group within the constraints of a racial hierarchy. And, although we zeroed in on the role of ideology as one predisposing factor in these choices, it stands to reason that there might be other moderators worthy of further investigation with more intricate research designs, including nativity, income, and language preferences (e.g., Garcia Reference Garcia2012; Lee and Pérez Reference Lee and Pérez2014).

Where do we go from here? There are many directions we can consider, but we close our paper by focusing on two that we consider especially important. First, our findings pose new questions about the psychological processes we have outlined. One of these questions is methodological. Although mediation analyses are useful in establishing viable psychological mechanisms—in this case, the role of racism in Latinos’ support for Black-centered policies—it is also the case that downstream associations between our mediator (racism) and outcomes are just that—associations. The upside is that our sensitivity analyses reveal that this connection is remarkably robust, suggesting we’ve hit upon a mediator that is worthy of further investigation. And part of that investigation, we think, involves manipulating, rather than simply measuring, levels of racism in light of our “downgraded American” treatment in Study 3. Of course, boosting levels of racism via random assignment raises ethical questions, which is why we originally took the route of measuring this mediator. But it is plausible that stronger causal evidence for this “racism-to-policy support” path could be gleaned by manipulating racism among Latinos in a way that reduces it, which would be more ethical and scientifically informative. This design could also lengthen the window (by days) between measurement of the mediator and measurement of the outcomes, which would provide additional leverage over the causal role of prejudice.

Second, there is the question of extending this framework to additional out-groups. On one hand, some work suggests that the dynamic we have observed here, where Latinos lash out at African Americans, is generalizable to other communities of color that share a station close to that of Latinos within America’s racial order, including Arab Americans and Asian Americans (Pérez and Kuo Reference Pérez, Crystal and Bianca2021; Zou and Cheryan Reference Zou and Cheryan2017). The basic logic here is that Latinos would be motivated to fully differentiate themselves from groups who are considered just as “un-American” as they are. But another possibility altogether is that what we have observed here is a function of anti-Blackness among nonwhite groups like Latinos. The idea here, advanced most visibly by David Sears and Victoria Savalei (Reference Sears and Savalei2006), is that the U.S. suffers from “Black exceptionalism” such that African Americans are the community of color at the receiving end of uniquely harsh hostility, marginalization, and oppression by both white and nonwhite individuals. Thus, a design that more extensively captures reactions to a variety of (non-)Black minority groups would be in a better position to throw light on these two important alternatives, with consequences for how we understand interminority conflict in a diversifying polity.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422000545.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/GMFAUC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our colleagues in the Race, Ethnicity, Politics & Society Lab and the Intergroup Relations Lab at UCLA, especially Tiffany Brannon, Pete Fisher, Yuen Huo, and David Sears, who offered crucial advice in the early stages of this work. We are also indebted to Chris Federico and his colleagues at the University of Minnesota, who invited us to share our work and receive critical feedback from political scientists and social psychologists alike. Finally, we thank Arturo Bustos Ochoa for his superb editorial assistance during this project.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors declare the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by UCLA’s Institutional Review Board and certificate numbers are provided in the text. The authors affirm that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.