This paper materialises the affective emergence of watery assemblages between sea, shark, swimming and British-Bangladeshi Muslim schoolgirls from my PhD research. Watery assemblages push my participants’ lived experiences further into another layer of ‘force field of differentiation’ (Alaimo, Reference Alaimo2010, p. 14) where stories, flesh and sea become discrete no longer, where the ground is not solid but watery, the movement is not walking or speaking but swimming and the body is not just human but human-animal. Watery assemblages enable the fluid and affective entanglements with complex and thick experiences of gender and racial harassment. Entangling with images and stories I explore how the affective and material agency of sea, swimming and shark as concept and performative multiplicity (Protevi, Reference Protevi2013) work as praxis and provocations for thinkings and doings. Inspired by Haraway’s notion of ‘becoming-with’ (Reference Haraway2016), in this paper I think and work with these provocative questions; what happens when you become-with a ‘liquid ground’ (Irigaray, Reference Irigaray and Gill1991) with water (Neimanis, Reference Neimanis, Taylor and Sharp2016) creating a ‘water-body assemblage’ (Renold & Ivinson, Reference Renold, Ivinson, Renold, Ringrose and Egan2015), when your ground is not a solid land with clear boundaries but a ‘watery deterritorialising machine’ (Lasczik et al., Reference Lasczik, Rousell, Ofosu-Asare, Foley, Hotko, Khatun and Paquette2020) that enables the force of differentiation and wellspring of unknowability (Neimanis, Reference Neimanis, Taylor and Sharp2016),when the body as an ‘open materiality’ (Grosz, Reference Grosz1994) does not walk and talk to become but swims far and deep towards a different body and becoming.

Thinking and working with sea resonates with indigenous tales as decolonising methodology (Tuhiwai Smith, Reference Tuhiwai Smith2012) and practices of knowing that cannot fully be claimed as human practices (Barad, Reference Barad2007); research practices that are not emerged from the prestructured specific academic disciplines but from everyday ordinary experiences of racial harassment and fear by Muslim schoolgirls that materialise through becoming with sea, swimming and shark. I think and write with sea, shark and swimming as middle-voiced verbs (Bennett, Reference Bennett2020) and nouns that enable partaking in more than ‘a linguistic practice’, an affective, material and immaterial entanglement with human and more-than-humans in different watery ground.

Watery Assemblages to Become-With

Inspired by the notion of thinking with water (Neimanis, Reference Neimanis2013, Reference Neimanis, Taylor and Sharp2016, Reference Neimanis, Christian and Wong2017; Krause & Strang, Reference Krause and Strang2016; Lasczik et al., Reference Lasczik, Rousell, Ofosu-Asare, Foley, Hotko, Khatun and Paquette2020; Strang, Reference Strang2014), I attend to emerging watery assemblages to think about the nomadic and fluid relationships between Maha and her relations to her own body, more-than-human bodies, hijab, family, community and the two areas where she lives. The watery assemblages that I map in this paper do not imply a concept I coined; rather, they were and still are a ‘call from things’ (Bennett, Reference Bennett and Cohen2012, p. 240) that my participant and I took seriously and pulled into. Watery assemblages in this paper are grown from my posthuman research on affective and material racialising assemblages (Zarabadi, Autumn Reference Zarabadi2022; Zarabadi, Reference Zarabadi, Dernikos, Nancy, McCall and Niccolini2020; Zarabadi & Ringrose, Reference Zarabadi, Ringrose and Talburt2018a, Reference Zarabadi, Ringrose, Riddle and Baroutsis2018b) that Muslim British-Bangladeshi schoolgirls experience in their everyday ordinary commute to and from school. From the beginning I did not know that the walking and photo-diary methodologies of my research would be channelled into human and more-than-human waterways. I propose that working with ‘liquid ground’ (Irigaray, Reference Irigaray and Gill1991; Neimanis, Reference Neimanis, Taylor and Sharp2016) might be a response to Halberstam’s question that she opened with in her book, The Art of Failure: ‘So what is the alternative? to articulate an alternative vision of life, love, and labour and to put such a vision into practice, to live life otherwise’ (Reference Halberstam2011, p. 2). She uses ‘low theory’ to locate the in-between spaces that enable us to move away from the hooks of hegemony. I suggest working with sea, shark, swimming and water resonate with using low theory, different watery spaces that disrupt the solid human-centred relations.

Maha is a Muslim British-Algerian girl who wears hijab but not through her own choice. She says she is ‘in an ongoing battle with my mum to not wear it’. She lives between two crowded family houses. Her parents are divorced and remarried. Maha has one younger full brother, four half siblings in her mother’s household and six half siblings in her father’s household. Maha is one of the participants of my PhD research who I met in a secondary school in southeast London. Using walking and photo-diary methodologies I walked and entangled with Maha in different spaces and times, in her commute to and from school, mostly through Skype intraviews where I was physically absent in the walkings but virtually present with Maha. My affective entanglements with Maha created ‘a certain queer affect’ (Halberstam, Reference Halberstam2011, p. 66) on me; to be attentive to the more-than-human agency, on Maha; to swim (speak) the unsaid and unheard in my research; and to think with water. The watery ground made different Maha possible, the virtual but actual one that the gendered, sexualised, racialised and religious normalising forces constrain its emergence. Sea, swimming and shark as agential collaborators become matters to think with rather than to think about.

The ChthuluceneFootnote 1 is made up of ongoing multispecies stories and practices of becoming-with in times that remain at stake, in precarious times, in which the world is not finished and the sky has not fallen — yet. We are at stake to each other…human beings are not the only important actors in the Chthulucene, with all other beings able simply to react. The order is reknitted: human beings are with and of the earth, and the biotic and abiotic powers of this earth are the main story. (Haraway, Reference Haraway2016, p. 55).

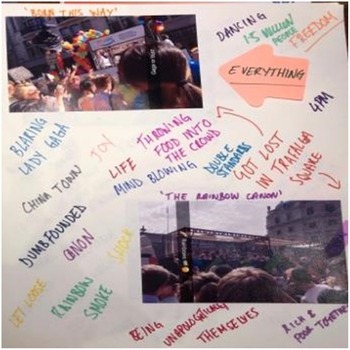

Maha’s multispecies stories and experiences of becoming-with sea, water and shark emerge in precarious times when Muslim lived experiences affectively, materially and discursively intertwine with terrorism, radicalisation, threat and fear proliferated in the public through Prevent policyFootnote 2 in and beyond school and media coverage of Muslim-related topics. Maha’s watery assemblage starts from a photo (Figure 1) in her photo-diary. The photo of a grey wintry beach with the thick cloudy sky, the horizon of entangled grey sea and sky, the dark emptiness and no-thing-ness in the photo.

Figure 1. Beach in winter? Why not? From Zarabadi (Reference Zarabadi2021).

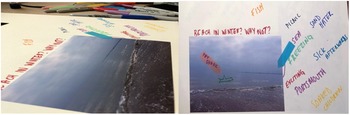

The fluid watery relationship of this photo resonates affectively and diffractively with the first two pictures of her photo-diary; ‘BORN THIS WAY’ and ‘THE RAINBOW CANON’, the only pictures in Maha’s photo-diary showing humans and the queer nonnormative fluid bodies at Pride in London, which she attended with her friends (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Born this way. From Zarabadi (Reference Zarabadi2021).

The watery relationships or ‘watery knots’ (Lasczik et al., Reference Lasczik, Rousell, Ofosu-Asare, Foley, Hotko, Khatun and Paquette2020, p. 156) that Maha becomes with forced me to think:

Why does water matter with Maha? What does water do to her subjectivity-becoming experiences? How does nature ‘call’ Maha, me and my research into the watery assemblages? What does water do to a subaltern who can or cannot speak? Does water give voice and /or potentiality to become fluid?

Maha makes the ‘agential cut’ (Barad, Reference Barad2007) to walking, to becoming and to the research. Drawing on Barad that difference is thought of as ‘agential separability’ (Reference Barad2007, pp. 176–177), making the cut through becoming/thinking with sea, Maha produces bodies of difference. She does not speak of her queer nonnormative sexuality in a normative way; rather, she swims to make fluid relationships to religion, hijab, family, gender and racial harassment and her queer unheard desires. Through the watery virtual assemblages she makes, her real virtual body becomes a ‘proto-body’ (Chandler & Neimanis, Reference Chandler, Neimanis, Chen, MacLeod and Neimanis2013, p. 83) that escapes the human agency of articulation:

Sea, I like sea, but we explore only one percent of the sea, no one knows what’s in there, and that’s crazy exciting. You are like, what is in there, what is hiding, what is going on, I think it might scare many people because they donʼt know what’s in the sea, but I find that cool. I am just that one person that go really far out to the point that I am a dot in a distance.

Inspired by Neimanis’s thinking with water, to become with Maha I consider water as specific, storied, situated, spirited and always more than just brute matter (Reference Neimanis, Taylor and Sharp2016, p. 59). The sea that ‘we explore only one percent of’ and Maha who is ‘the one person that goes really far out to become a dot in a distance’ mutually become a political agency to materialise complex embodied and embedded relations of power, control and belonging. As Lasczik et al. (Reference Lasczik, Rousell, Ofosu-Asare, Foley, Hotko, Khatun and Paquette2020) suggest, ‘although water is often theorised as a life-creating, life-connecting source of abundance, it is also a technology for unjust political determinations of affluence and poverty, toxicity and health, freedom and control, flourishing and death’ (p. 158). The materiality of water enables an understanding of water not as neutral rather as agentive co-constituents of relational meaning within society (Krause & Strang, Reference Krause and Strang2016, p. 633). Drawing on Foucault, water can be considered as ‘both political and bio-political’ (Bakker, Reference Bakker2012) which is used by governments to control water resources, our individual water-use practices and health and productivity of the population (p. 616). Moving beyond the Foucauldian understanding of political agency of water, and taking the posthuman affective thinking with water, I argue that in those material moments of our research encounters, water had agentic and affective capacity to enable Maha to become otherwise. The banning of wearing a burkini, a full-body swimsuit that covers everything except the face, hands and feet on public beaches and in pools, has been one of the ongoing political debates of the past few years.Footnote 3 Muslim women and their engagement with water was/is always a media headline. Water agentically enables possibilities and impossibilities, it materially affects, enables and/or constrains who can/canʼt go in the water and how. Maha agentially has cut the normalising controls of the relations between a Muslim woman’s body and water; she chooses to swim to talk about herself differently, a kind of talking that sounds through swimming, movement, body and water; a ‘water-body talk’ (Renold & Ivinson, Reference Renold, Ivinson, Renold, Ringrose and Egan2015, p. 249).

They [her parents] don’t like it [swimming], was it on purpose [to swim far out in the sea]? It was on purpose, and I just come back and then I go in later because they know I am a strong swimmer and I am not stupid, and I am not gonna go to a point where I canʼt get back.

Maha purposefully swims far to get to a point about herself, a dot, her ‘watery sexuality’ (Neimanis, Reference Neimanis, Christian and Wong2017, p. 54), gender and religion. Water’s capacity of dissolution, communication, differentiation and unknowability enabling a watery sexuality emphasises not the reproduction of the same, but the capacity to gestate difference (Neimanis, Reference Neimanis, Christian and Wong2017). Thinking through what I call ‘watery assemblage’ provides me with a different understanding of Maha’s material relations to hijab, Muslim-ness, gender and sexuality. Unlike other participants of my research, Maha never calls her hijab either a scarf or hijab, but ‘it’. She does not wear ‘it’ in a fashionable way, wrapping it around the head in different colours; rather, she simply ties ‘it’ under her chin using a pin. She does not like make-up and never wears any. She hangs out mostly with boys and always wears trousers as part of her school uniform. Her relationship to hijab is what my participants call ‘on and off’; she wears ‘it’ in her mothers’ house, to school and the Peckham neighbourhood and does not in her father’s house and around Stratford.

Her watery material and nomadic assemblage with hijab, religion, family, body, like the water that returns, repeats, diffracts, resists, tides, fluxes and whorls, take up the movements of water. Water’s hydro-logic of gestationality as a life-giving ground facilitates plurality and the future unknown to come (Chandler & Neimanis, Reference Chandler, Neimanis, Chen, MacLeod and Neimanis2013; Neimanis, Reference Neimanis, Christian and Wong2017). As Haraway says:

The slight curve of the shell that holds just a little water, just a few seeds to give away and to receive, suggests stories of becoming-with, of reciprocal in-duction, of companion species whose job in living and dying is not to end the storying, the worlding. With a shell and a net, becoming human, be-coming humus, becoming terran, has another shape — the sidewinding, snaky shape of becoming-with. (Reference Haraway2016, p.119)

Maha, ‘that one person’ who swims to become with the 99 per cent of the unknowable sea and a dot in a distance, bathes new and different watery assemblages to the relational materialities of her lived experiences. Becoming with the unknowability of water and a dot in a distance, connects with the affective experiences of ‘GOT LOST IN TRAFALGAR SQUARE’, ‘FREEDOM’, ‘RICH AND POOR TOGETHER’ AND ‘BEING UNAPOLOGETICALLY THEMSELVES’ which Maha materialises in her photo of Pride in London (Figure 2).

Becoming-Shark

Maha draws a shark on the picture of the grey wintry sea (Figure 3) during our photo-diary making research encounter that happened at her school. The slow emergence of the shark created another ‘queer affect’ (Halberstam, Reference Halberstam2011, p. 66) in space, time, bodies and relations.

Figure 3. Becoming shark. From Zarabadi (Reference Zarabadi2021).

The emergence of the shark forced me to think:

What does shark do to Maha, me, and my research? Is the shark another agential collaborator to Maha’s watery assemblage? What does shark call us for?

Maha is on the beach with her mother and her four other siblings; she is always responsible for taking care of her siblings. Despite the SEA is FREEZING, CHILDREN are SOAKED wet and became SICK AFTERWARDS, Maha finds wintry sea exciting and writes in red, BEACH IN WINTER? WHY NOT? (Figure 1).

…It’s [the sea] not shark-infested or anything, theyʼre scared of sharks, instead give the sharks the respect they deserve.

The shark queers the sea and creates affective intensity in the moment, in the grimness and emptiness and a wintry sea, turning conventional relations, experiences and research creative, watery and different. Maha laughs and says, ‘Let’s draw a shark, I love shark’. She draws a shark in green, with just a dot for an eye (Figure 3):

I donʼt know why people get scared of sharks, they are just trying to live their life, they just exist and donʼt do anything to you.

I am glued to the one green dot, Maha’s shark eye:

Um, just pretend that it’s a shark. It’s a whale but it’s a shark too.

She stares at the picture:

It’s my pet shark. I have decided this is my pet shark.

In Neimanis’s (Reference Neimanis2007) essay Becoming-Grizzly: Bodily Molecularity and the Animal that Becomes, she asks: ‘how might we understand becoming-animal as a modality of our lived, embodied experience? (p. 279). Drawing on Deleuze & Guattari’s notion of ‘becoming-animal’ (Reference Deleuze and Guattari1987, p. 238) the notion that all becomings, are ‘molecular’ (pp. 272–275), Neimanis argues that the collision of human molecularity and animal molecularity, rather than being a ‘representation’ or an ‘imitation’ of one part or another, are a co-mixing and co-mingling (p. 282). As Neimanis suggests, becoming-animal within Deleuze & Guattari’s philosophy is one figuration of difference seeking to undermine the Western human-centred understanding of the world and the belief in the stable hegemonic and subjectified human condition (p. 283). The affective and material co-mingling of Maha and the shark do not just ‘pull(s) us out of our place of human privilege’ (Neimanis, Reference Neimanis2007, p. 283) but Maha, being a queer nonreligious Muslim girl and part of this watery assemblage, pulls us into the different thick lived experiences of her life. As bodies are molecular co-compositions of material, affective, temporal and spacial and not only sedimented subjects (Neimanis, Reference Neimanis, Christian and Wong2017, p. 290), Maha has a potentially shared molecularity with the things she seeks to describe. The shark provides what Neimanis (Reference Neimanis2007, p. 300) calls ‘look at me moments’ to Maha’s watery assemblage, to her thick lived experiences of gendered, sexual and racial harassment and living in two overcrowded households. Sea, shark and swimming give Maha a different life to become intelligible during our research encounters.

Drawing on Braidotti, I consider shark as a queer ‘figuration’ and a ‘living map’ (Reference Braidotti2011, p. 10) that not only marks concretely the situated historical positions (Braidotti, Reference Braidotti2006, p. 90) but also a feminist protest and a ‘literal expression’ of those parts of our subjectivity that the ‘phallogocentric [white heterosexual and religious, western] regime’ has ‘declared off-limits’ and ‘does not want us to become’ (Braidotti, Reference Braidotti2006, p. 170). In Maha’s story, shark is not a speculative concept that we made, but a real figuration that called us and enabled us to think-with thickness of Maha’s lived experiences. For Deleuze & Guattari (Reference Deleuze and Guattari1987) real is both actual and virtual, the lines of articulation and stratification of what have been already assembled and straited and the lines of flight opening us up to transformation, creativity, newness and ‘the cloud of indeterminate potentiality that hovers around this stratification’ (Neimanis, Reference Neimanis2007, p. 282). The emergence of the shark as an intense affect, as Deleuze & Guattari suggest, is not about madness or losing connection with reality rather as a profound experience and moment can be considered as a breakthrough to ‘more reality’ (Deleuze, Reference Deleuze2006, p. 25). A longing for otherness that is experienced through ‘the virtual collection of potentiality, making possible connections and couplings with all manner of matter’ (Ivinson & Renold, Reference Ivinson and Renold2013, p. 372). Working with Maha’s becoming shark, as a Muslim queer girl, the notion of real is more aligned with Tuhiwai Smith’s understanding of ‘real’ (Reference Tuhiwai Smith1999), that moves away from the Western-dominant conceptual framework and the project of colonisation and determining value (pp. 42–57). Shark becomes an affective and material channel for Maha’s nomadic and ‘watery subjectivity’ (Neimanis, Reference Neimanis2013, p. 26) that is not purely discursive or solely biological, but instead an ‘open materiality’ (Grosz, Reference Grosz1994: 191) to emerge; effectively, a real material virtual but actual Maha that can only become/swim in the sea and as a shark.

Swimming, the Embodied Middle-Voiced Action

I think with Deleuze’s striated and smooth space (Reference Deleuze2004, p. 408, pp. 524–525) to understand how Maha becomes with sea, water and swimming, as smooth spaces to disrupt the striated spaces of gendered, racialised and sexualised harassment, her (Muslim and non-Muslim) community, family, neighbourhood and school. Becoming with these smooth spaces enables her, me and my research to work with/swim with different flows of energy and intensity of ‘that one person’ to materialise herself differently. Akin to smooth spaces where ‘there is no line separating earth and sky’ (Reference Deleuze2004, p. 421), sea, shark, water and swimming have no hierarchical, strictly and intensive rule-bounded lines to constrain Maha’s body, feeling and desires. Swimming with waves and currents, like water, she comes to the shore and comes back, each time a new ‘turning and re-turning’ (Benozzo et al., Reference Benozzo, Carey, Cozza, Elmenhorst, Fairchild, Koro-Ljungberg and Taylor2019) that is the ‘dynamic and generative, invigorating past/present/future connections that dissolve the Cartesian boundaries on nature/culture to generate new knowledges and experiences’ (p. 89):

I just like trying new things, like I am gonna try cold water swimming in Dec, I like weird things that catch your eyes, debate clubs they are everywhere.

In line with their ecofeminist pedagogy and activism Appleby & Pennycook (Reference Appleby and Pennycook2017) swim with sharks to call for a renewed and different politics of engagement with the not human things. Swimming with sharks for them is not like dominant masculinist discourses and acts of heroic countering and battles with sharks, but rather a critical practice for restorying colonised places and to coming to know the world differently (p. 6). Shark encounters as material, discursive, textual, embodied, politicised and technologised experiences can become the basis of an entangled pedagogy (Appleby, Reference Appleby2016). As Appleby & Pennycook argue, their pedagogical practices of swimming with shark do not only encompass a range of actants, their histories, trajectories, effects and the consequences of their interactions for environmental sustainability and ecosystem survival, but also offer ‘a provocation for students to explore and reflect on their own daily encounters and puzzlements in the natural world’ (Reference Appleby and Pennycook2017, p. 15). For Maha, this watery collection of human and more-than-human bodies enables a different Maha to be actualised.

Knowing with Prosthetic Vision

Sea, water, shark and swimming as a ‘prosthetic vision’ (Haraway, Reference Haraway1988) allow haptic entanglements with the relational materialities of Maha’s subjectivity-becoming. In this ‘haptic’ experience, sea, shark, swimming and water found a sensory intrarelationality with different mediums; hands and legs that move, mouth that breaths, eyes that stay closed, to talk. For Deleuze & Guattari (Reference Deleuze and Guattari1987) haptic ‘does not establish an opposition between two organs but rather invites the assumption that the eye itself may fulfil a non-optical function’ (p. 492). As the haptic sense liberates the eye from its belonging to an organism, I use this concept in this watery assemblage to argue how the methodological affordances of working with nature can provide different potentialities for things that matter but it’s hard to say are haptically materialised. I am forced to think:

Do shark, sea and swimming enable knowing lived experiences of Maha that I couldn’t know, or that she could talk about herself?

Haraway argues these entanglements with more-than-human agencies extend and diffract our own situated knowledges however these knowledges stay partial. Therefore, this is not to say that I found a firm standpoint to claim I fully know Maha. However, such watery assemblages with human and more-than-human bodies materialised what Barad suggests that agency can never ‘run out’ (Reference Barad2003, p. 177) and it never ends. Neimanis borrows Irigaray’s ‘thinking with matter’ (Reference Irigaray and Gill1991), to re-think the relations of human body to more-than-human waters (Reference Neimanis, Taylor and Sharp2016, p. 48). Water, sea, shark and swimming as more-than-human agencies and lively matters, enable Maha to re-materialise her relations in a way that she couldnʼt do in just walking, speaking and writing. When swimming, Maha and I, with my research, become ‘middle-voiced partakers who are more than either actors or recipients’(Bennett, Reference Bennett2020, p. 114). Sea-ing instead of see-ing, swimming instead of speaking and becoming shark to understand the lived thick experiences of differentiated bodies. For Bennett this onto-condition ‘can absorb fascist and racist and other hateful currents — a danger to be combatted not only by applying filters or turning away but also by widening the entry-points for laudable flows of affect’ (Reference Bennett2020, p.114). I am wondering if ‘to swim’ could be part of Bennett’s list of middle-voiced verbs ‘to promulge, to sing, to dab and sail, to animate’ (Reference Bennett2020, p. 113), not only as a linguistic practice to ‘write up processual agencies’ (Reference Bennett2020, p. xix) but also to affectively, materially and immaterially entangle with human and more-than-humans in the research practices in different ground, watery. Pedagogical agency of water and its political materiality teaches us that any knowledge production like water is ‘slippery, drippy, rushing and by nature shapeshifts into hard ices and steamy clouds’ (Lasczik et al., Reference Lasczik, Rousell, Ofosu-Asare, Foley, Hotko, Khatun and Paquette2020, p. 157); it transforms. Swimming/thinking with water, sea and shark in becoming slippery, watery, dripping is akin to using ‘low theory’ (Halberstam, Reference Halberstam2011), to work with creativity and surprise that failing, losing, forgetting, unmaking, undoing, unbecoming and not knowing may bring (p. 3). Such watery assemblages and methodologies resonate with Knight’s ‘inefficient mapping’ (Reference Knight2021) in responding to neoliberal research culture and global conservatism. Inefficient mapping as a creative interaction with the world, embraces the partiality or inefficiency to think methodologically with speculative and immanent theories, to make apparent new forms of association (p. 13) and to attune to nonrepresentational affects and energies of place, space, and event (p. 225).

Neimanis, drawing on Spivak who asks whether the ‘subaltern can speak’, equates the colonised subaltern human bodies with natural, nonhuman ones (Reference Neimanis, Christian and Wong2017, p. 58). For Spivak it is impossible for a subaltern to speak because the context is already constructed by dominant populations. Spivak criticises Western intellectuals who seek to ‘speak for’ marginalised populations. Thinking with water Neimanis suggests that ‘in this way of knowing more speech [read: more control] does not generate better knowledge. Speech domination does not equal more wisdom’ (Reference Neimanis, Christian and Wong2017, p. 61). This forced me to think:

Why does Maha become with nature? How does nature call her?

Maha speaks through/with/of the materiality of water. Maha, ‘that one person’, who is a nonreligious queer Muslim, turning to the nature, sea, water and shark forced me to think about the normative nature/culture dichotomy and how it has historically created ‘natural others’, non-White, non-Western women. Nature within the Western colonial apparatus is not only nonhuman or more-than-human but is also less-than-human and subordinated. Body, emotions, physicality and nature are attributed to women and therefore women are socially constructed as irrational, primitive, passive objects of hu(man) rational minds. In such a patriarchal anthropocentric view, ‘nature is naturally considered as inferior because it is natural, and woman is inferior because she is natural, and the natural is inferior because it is feminine, which is inferior, which is natural … and so on’ (Neimanis, Reference Neimanis, Christian and Wong2017, p. 29). Maha’s turning/re-turning to nature, transversally cuts across artificial binaries of human/nonhuman, nature/culture, living/nonliving, male/female, us/them, White Western/non-White heterosexual/nonheterosexual, Muslim/non-Muslim, etc. For Braidotti, ‘transversal forces cut across and reconnect previously segregated species, categories, and domains’ (Reference Braidotti2013, p. 60). Sea, shark and swimming enable those transversal forces for Maha to become differentiated. Her becoming with sea and shark create openings across various queer and nonnormative relations and possibilities she likes to become with. She finds a ‘trans-corporeal’ (Alaimo, Reference Alaimo2010) capacity, an extended embodied and embedded agency distributed across ‘human bodies, nonhuman creatures, ecological systems, chemical agents, and other actors’ (p. 2). I take up Ulmer’s (Reference Ulmer2017) accounts of Haraway’s figurations of companion species and cyborgs as transversal trans-species relations that provide potentiality for alternative interconnections, relations and nonhuman agencies to emerge (p. 837).

Conclusion

I mapped the emergence of watery assemblages and their agential relational powers to enable possibilities for different subjectivity experiences to happen. The vital posthuman political agency of sea, water, shark and swimming provide material potentiality for the enfleshed, embedded, watery and fluid stories of a queer Muslim schoolgirl to become intelligible. Akin to the sea of Pride in London, nonnormative queer bodies of humans, the watery assemblage of Maha, sea, water, shark and swimming, gave different life to sexuality, religiosity, relationships with family and community; a fluid, nomadic, watery and queer becoming. I proposed that thinking and working with nature can enable the subaltern to speak not in the hegemonic colonial anthropocentric language of hegemonic power but with vital materiality of sea, water, shark and swimming. These watery moments emerged during the photo-diary research encounter cut across many normalising relations with human and more-than-human bodies, like waves, the desires, feelings and bodies tide, flux, whorl, turn and re-turn to the shores, each time differentiated.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical Standard

This paper is drawn from my PhD thesis; Racialising assemblages and affective events: A feminist new materialism and post-human study of Muslim schoolgirls in London and carried out at the UCL Institute of Education. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of UCL Ethical Committee. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in my PhD thesis and names of the participants are Pseudonym.

Dr Shiva Zarabadi holds a Ph.D. in Education, Feminist New Materialism and Posthumanism from UCL Institute of Education. Her research interests include feminist new materialism, posthumanism and intra-actions of matter, time, affect, space, humans and more-than-humans. She uses walking and photo-diary methodologies to map relational materialities in ordinary practices.