Introduction

We are living in an age of political turbulence, social division, and resistance. The resistance that formed in reaction to the election of Donald Trump styles itself a force to defend constitutional rights, democratic norms, and the rule of law in the United States. Perhaps the New Republic best explained its advent: the Resistance had been born of partisan—that is, Democratic—fury after “liberalism had been dealt its most stunning and consequential defeat in American history.”Footnote 1 “For the first time in decades, liberalism has been infused with a sense of energy and purpose,” with millions of people devoted to a singular cause: resisting Trump.Footnote 2

I agree that the millions-strong nationwide protests, the array of state and locally based efforts to win back electoral power—and the subject of the furor, Donald Trump—are remarkable in many ways.

Nevertheless, it seems to me that we—as citizens and as scholars—ought to contextualize and historicize this moment with a view toward assessing where it stands in the long arc of American history. What is happening here?

Many writers have turned to the Tea Party to describe this moment.Footnote 3 As I will explain momentarily, I find this analogy curious and mostly inapt.

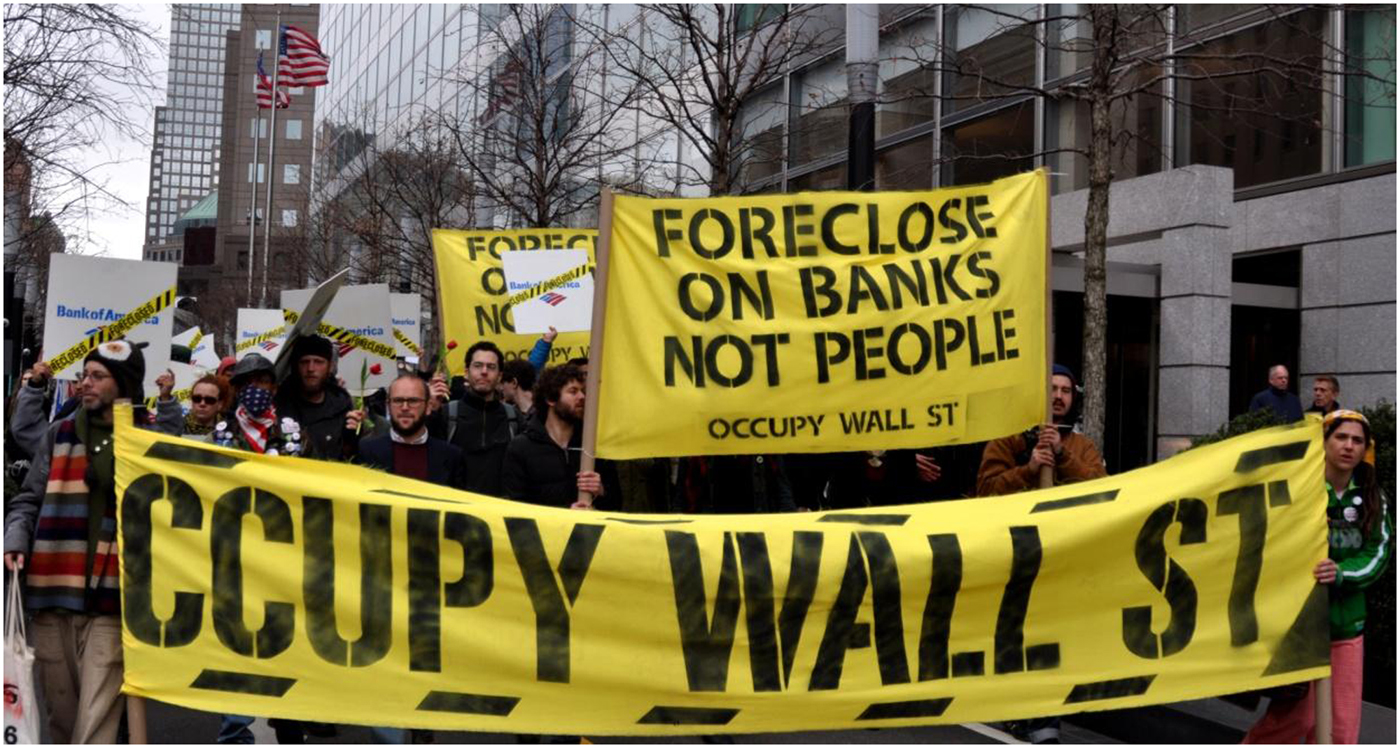

I see the current Resistance in relation to activism that stretches back to the anti-World Trade Organization (WTO) protests,Footnote 4 Occupy Wall Street,Footnote 5 the fight for a $15 minimum wage,Footnote 6 the Movement for Black Lives,Footnote 7 and the scattered protests against the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that preceded the Tea Party.Footnote 8

All these recent protests were reactions, in part, to structural economic and political inequalities: disparities linked to the global flow of trade and people. Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel Prize-winning economist, warned us that the capture and corruption of the political system by moneyed interests could create profound instability.Footnote 9 That movement has arrived: backlash against structural economic and political inequality is the tie that binds contemporary movements on the Right and the Left.

What is more, the recent movements are connected conceptually to the unfinished business of the mid-twentieth-century resistance movements for labor, civil and women's rights—movements that, in turn, tackled unresolved eighteenth- and nineteenth-century conflicts over social and economic inequality—the subjects of the abolitionist, suffrage, and progressive movements. Altogether, these movements struggled to uproot Founding era commitments to property rights over human rights, while affirming Founding and Reconstruction era promises of liberty and equality.Footnote 10 Therefore, far from being only or even mostly about the present occupant of the White House, the current Resistance reflects a long and contentious struggle over the nature of the American social contract itself.Footnote 11 That, I suggest, is what is happening here.

Three Observations about Twentieth-Century Social Movements

Having offered a big picture analysis of the relationship between the present and the past, I now want to engage in a more granular analysis, in hopes of illustrating continuity and change in the ways in which struggle over the social contract has found expression over time. Analyzing these movements from within, or bottom up, as well as top down, or from the perspective of external phenomena and elite institutions, I offer observations about three inter-related issues: (1) how progressive social movements historically have deployed rights talk to press agendas for structural social and economic change—not merely to overthrow a political figure; (2) how these movements have engaged political parties and electoral politics; and (3) how historical memory of these eras fails to sufficiently reckon with counter-movements on the Right or with political mobilizations on the Left of the working class and poor, particularly people of color. Both mobilized groups are highly relevant to our world today.

Rights Talk

First, let us consider protest movements and rights talk. One of major goals of the current Resistance, say various mission statements, is affirmation of the rule of law.Footnote 12 It turns out that protest movements have long deployed the rhetoric of democratic constitutionalism to frame disputes and move forward their agendas, but often in a different voice than today.

Mobilized groups invoke a thick conception of law—not only the Constitution—the “paramount law,” to quote Chief Justice John MarshallFootnote 13—but the aspirational language of the Declaration of Independence and the Preamble to the Constitution; loose interpretations of case law, and popular understandings of what law should be.

Movements invoke rights talk in four major ways: (1) to make legal claims, (2) for moral suasion, (3) for cultural identification, and (4) for political mobilization. Which is to say: social movements deploy legal concepts strategically, and much more supplely than is possible in formal settings where judges are the primary interpreters of the law.Footnote 14

The Long Civil Rights Movement

The twentieth-century civil rights movement constitutes perhaps the best example of a social reform campaign's appropriation of constitutional and legal constructs in these ways. The movement—composed of many different organizations—deployed law in ways befitting each group.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Legal Defense Fund (Inc. Fund), led by a self-consciously professional cadre of lawyers and top-down leaders, turned to text- and history-based constitutional arguments to claim rights.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) spearheaded by ministers, deployed aspirational legal rhetoric for moral suasion.

The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), anchored by radical student activists and supported by “movement lawyers” inclined toward collaborative lawyering styles, referenced legal precepts for cultural critique and political mobilization.

All together, these institutions—working in a dynamic geopolitical environment—pushed the public, the courts, and Congress to dismantle Jim Crow.

Law for Claims-Making in the Black Freedom Struggle

The campaign to end Jim Crow in schools is the archetypical example of legal claims-making by a social movement—one that also highlights enduring conflict within and outside of movements over the priority to assign to structural economic inequality.

Thurgood Marshall served as the chief attorney translating the movement's grievances into legal claims, and he jealously guarded his strategy in the face of critics who preferred a different one.Footnote 15

Those critics included A. Philip Randolph, the labor leader. Randolph acknowledged that the Constitution's open-ended language could support many interpretations of the law, but he worried that federal courts would misinterpret, water down, or simply reject legitimate claims.Footnote 16 Randolph urged black and white workers to unite, form unions, and struggle as a collective for higher wages and better working conditions.Footnote 17

However, Marshall insisted “the way to change America was through the courts,”Footnote 18 and he laid claim to the Constitution as amended during Reconstruction: the period that W.E.B. DuBois called African-Americans’ “brief moment in the sun.”Footnote 19 And, as a result of external factors such as the war against fascism, juxtaposed to Jim Crow, which exposed American hypocrisy; the activism of black veterans; and lynchings that dramatized the depravity of white supremacy—Marshall and his team prevailed in Brown v Board of Education.Footnote 20

The Inc. Fund largely left it to other institutions, including organized labor and federal agencies, to pursue a labor–civil rights agenda, as scholars such as Sophia Lee and Nancy MacLean have demonstrated.Footnote 21

Law as Moral Resource

Dr. Martin Luther King—the leader-agent of campaigns against segregation in Montgomery, Birmingham, Selma, and Chicago—deployed rights talk for moral suasion—a use that allows the layperson a great deal of interpretative space.Footnote 22 Dr. King frequently invoked constitutional concepts such as “liberty, equality, and citizenship,” the idea of the rule of law, the words of the Declaration of Independence and Brown v Board of Education, to argue that racial discrimination violated the laws of both God and humanity.Footnote 23

Montgomery

Dr. King brilliantly articulated these views during the famed Montgomery Bus Boycott, when he told an audience at the Holt Street Baptist Church that the rights belonging to citizens in a constitutional democracy justified the boycott. “We are here, Dr. King said, because first and foremost—we are American citizens, and we are determined to apply our citizenship—to the fullness of its means. We are here… because of our love for democracy, because of our deep-seated belief that democracy transformed from thin paper (that is, the Constitution and laws) to thick action is the greatest form of government on earth.”Footnote 24

Dr. King also invoked Brown, decided a year before the boycott, to justify the protest, saying: “If we are wrong, the Supreme Court of this nation is wrong. If we are wrong, the Constitution of the United States is wrong. If we are wrong, God Almighty is wrong.”Footnote 25

In Dr. King's telling, one violation of the equal protection clause necessarily gave rise to another, a claim that constitutional scholars of the era found debatable,Footnote 26 but Dr. King was not counting on law professors to lead the movement. His rhetoric—including the loose reading of Brown—worked for a religious audience of non-lawyersFootnote 27 He inspired the movement's proponents and put opponents on the defensive.

It is by articulating a vision of equality “deeply rooted in the American Dream,” as Dr. King explained at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963Footnote 28—and by coupling public addresses with nonviolent protests in the face of violent white resistance—including beatings, bombings, and murders, including of children—that Dr. King and the communities he mobilized laid the groundwork for enactment of the omnibus Civil Rights Act of 1964Footnote 29 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, called the nation's “finest hour.”Footnote 30

The Movement and Economic Inequality

Nevertheless, the matter of economic inequality that A. Philip Randolph and others earlier had raised remained.Footnote 31 Now, everyday people—mobilized by the movement but dissatisfied with the partial reforms embodied in antidiscrimination law—raised their voices: the radical labor activists in New York whom Martha Biondi describes,Footnote 32 the proponents of black power in Philadelphia whom Matthew Countryman writes about in Up South,Footnote 33 organizers in Mississippi whose activities Charles Payne documented,Footnote 34 and welfare rights protesters in Atlanta who are the third wave of dissenters in Courage to Dissent, Footnote 35 all made economic opportunity central to their agendas.

Dr. King heard the call, Thomas Jackson explained in From Civil Rights to Human Rights.Footnote 36 His commitment to a social contract that lifted the poor of all races found full expression during the mid-1960s. Dr. King visited slums in the urban North and South and argued that all Americans bore responsibility for conditions in the ghetto.Footnote 37 He turned to President Lyndon Johnson for solutions, demanding a “massive assault upon slums, inferior education, [and] inadequate medical care.”Footnote 38 Dr. King sought job training and a guaranteed minimum income for all Americans.Footnote 39 In 1965, Dr. King's analysis deepened. He spoke about the violence of poverty; he called imprisoned black men the “legion of the damned in our economic army.”Footnote 40 In 1966, he observed that “depressed living standards” for the working poor were a “structural part of the economy,” and that certain industries grossly profited from a steady supply of “unskilled” laborersFootnote 41—critiques that should sound familiar decades later.

And in Memphis in 1968, Dr. King took up mantle of the labor movement. In “I've Been to the Mountaintop,” his final public address, King defended the workers’ agenda and their protest and urged America to “[b]e true to what you said on paper.” “Somewhere I read of the freedom of assembly. Somewhere I read of the freedom of the press. Somewhere I read the greatness of America is the right to protest for right.”Footnote 42 For the last time, Dr. King brilliantly deployed the Constitution to advance freedom for blacks, for whites, for workers: for downtrodden Americans everywhere.

Dr. King's foregrounding of economic justice engendered controversy. Some argued that Dr. King should, in essence, stay in his lane.Footnote 43 Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan claimed that “pathology” largely explained blacks’ ills.Footnote 44

But others, including Dr. King's lieutenant, Bayard Rustin, and student activists, endorsed the broader agenda.Footnote 45 And now, let us consider that strand of the movement, a turn that will illustrate how activists deployed law as cultural and political resources.

Law as Cultural and Political Resources

First, I will consider SNCC, the student group nurtured by organizer Ella Baker, which consciously adopted an arsenal of tactics that varied from those favored by Dr. King and Thurgood Marshall.Footnote 46 Like King and Marshall, SNCC deployed “rights talk.” However, if Marshall made legal claims, and Dr. King evoked law for moral suasion, SNCC invoked the nation's founding documents and court cases to engage in cultural critique and to politicize and organize local people.Footnote 47 If Marshall and the early Dr. King hoped to achieve reform by currying favor with the nation-state, SNCC hoped to be a countervailing force to elite domination and, if necessary, achieve freedom outside of the prevailing structures of society.Footnote 48

SNCC alluded to what Edwin Corwin called the “cult of the Constitution” to expose American hypocrisy and to press an expansive agenda.Footnote 49 In SNCC's telling, desegregation was a necessary, but insufficient, precondition to freedom.Footnote 50 The students also demanded affordable housing, community schools, political power, and fair policing.Footnote 51 Officers routinely brutalized blacks, particularly in impoverished communities; in fact, many officers, including Atlanta's chief of police from 1947 to 1972, were members of the Ku Klux Klan.Footnote 52 SNCC challenged American society, including liberal reformers in the NAACP, in the White House, and on the Supreme Court, to reject hypocrisy.Footnote 53

Striking a contrast to Dr. King, who had praised Brown, SNCC argued that the Court's actions in Brown’s aftermath illustrated that American institutions had failed African Americans.Footnote 54 And the students cited disillusionment with courts and lawyers to justify more participatory tactics, a repertoire that included sit-ins, boycotts, picketing and community organizing, and a broader substantive agenda. The participatory forms of protest added something that court-based activism lacked: political struggle, unmediated by formalities, rules, lawyers, presidential politics, or judges in robes.Footnote 55 John Lewis explained it best. “[W]e were all about” a “mass movement, an irresistible movement of the masses. Not a handful of lawyers in a closed courtroom, but hundreds, thousands of everyday people … taking their cause and belief to the streets.”Footnote 56

At the same time, SNCC continued to make claims on the law, only mostly outside of the courts, for their own purposes, and without a core belief in the efficacy of law. In protests in Atlanta, the students argued that foundational legal texts made promises that were not real, but fictive.Footnote 57 One might say that these students, like A. Philip Randolph, were proponents of the idea that rights are “illusory.”Footnote 58 All of these activists believed that the “myth of rights,” to quote Stuart Scheingold, facilitated oppression.Footnote 59

Resistance Today

As I think about today's Resistance and its rule of law goal, compared to the array of groups and legal tactics of yesterday, I am most struck by differences, rather than continuities. Although it is true that the Resistance—and the lawyers who, independently of it, have filed claims over emoluments and travel bans—charge this administration with violating constitutional norms, similarly to past movements that I have surveyed,Footnote 60 more striking is the difference between the rhetorical strategies of the Resistance and those of these prior movements. Unlike these prior movements,Footnote 61 the Resistance does not seek to build consensus between groups in conflict by emphasizing shared values, unifying themes, or a common purpose.

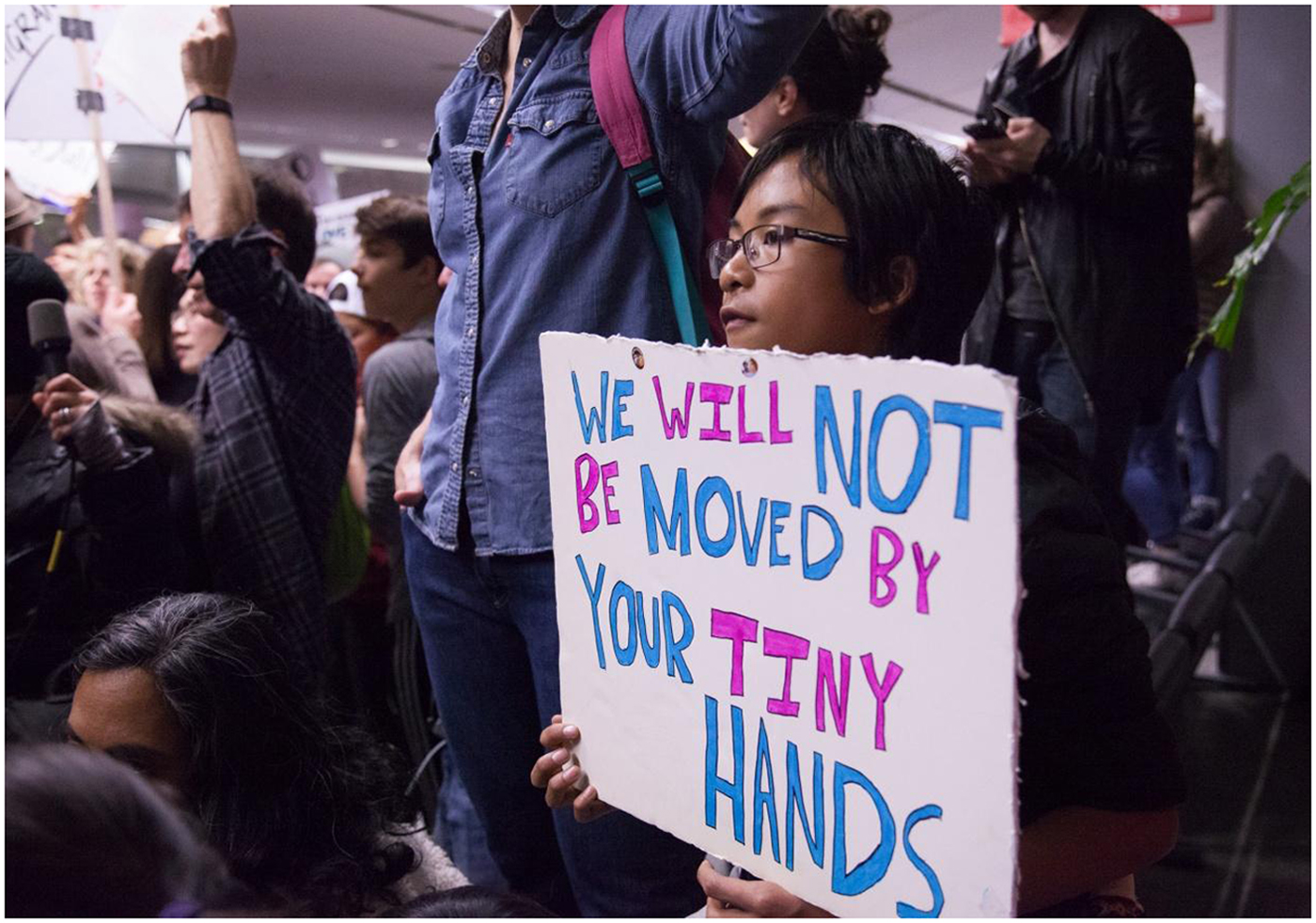

Much of the rhetoric employed by the Resistance is very specific, rather than abstract or inspirational. Marchers have held signs with allusions to “Resist,” “Resist Bigly,” and being “Woke,”Footnote 62 as well as to Women's Anatomy Grabbing Back,Footnote 63 Male Anatomy,Footnote 64 Hitler, Facism,Footnote 65 Not My President,Footnote 66 and Not My Cheeto.Footnote 67 And my favorite sign of them all said: “It's so bad, even introverts are here!”Footnote 68 This is scathing and incredibly amusing rhetoric—the kind that goes viral and is tweeted and retweeted.

The Resistance has made us laugh, but has it persuaded those not already inclined to support its point of view (and its sense of humor)? Such efforts to persuade might be premised on the kinds of eloquent critiques observed in the strands of the civil rights, women's rights, abolition, and suffrage movements discussed here. To my knowledge, the Resistance has not embraced rhetorical strategies premised on unifying legal precepts and national ideals: speech designed to rally friends and persuade enemies. And, I wonder if the frenzied pace of our time, facilitated by digital platforms, has undercut the sustained, intellectual, cultural, and political work in the public square necessary to persuade the public of the rightness of a protest movement's claims. Such narrative strategies are, it seems to me, a necessary precondition to political and legal change, which is based, after all, on the persuasive arts.

The Long Resistance: Abolitionism

I mentioned abolitionism, and I want to return to it to drive home the temporal point that I hope to make. Dr. King once observed that the “arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”Footnote 69 The concept of the “long resistance” embeds in scholarship the expansive temporal element that Dr. King referenced. Scholars such as Jacqueline Dowd Hall have argued for a “long” conception of the civil rights movement, one that locates its roots in the labor conflicts of the 1930s.Footnote 70 Other scholars advocate an even longer temporal arc, one that stretches the movement's heritage back to the nineteenth-century fight against slavery: the defining struggle over labor in the United States.Footnote 71 It is especially important now to reckon with slavery and abolitionism, it seems to me—in an age when scholars such as Sven BeckertFootnote 72 and Edward BaptistFootnote 73 have explained how global slavery laid the groundwork for both modern prosperity and modern inequality—and when communities contend, sometimes violently, with monuments to slave holders and Confederates.

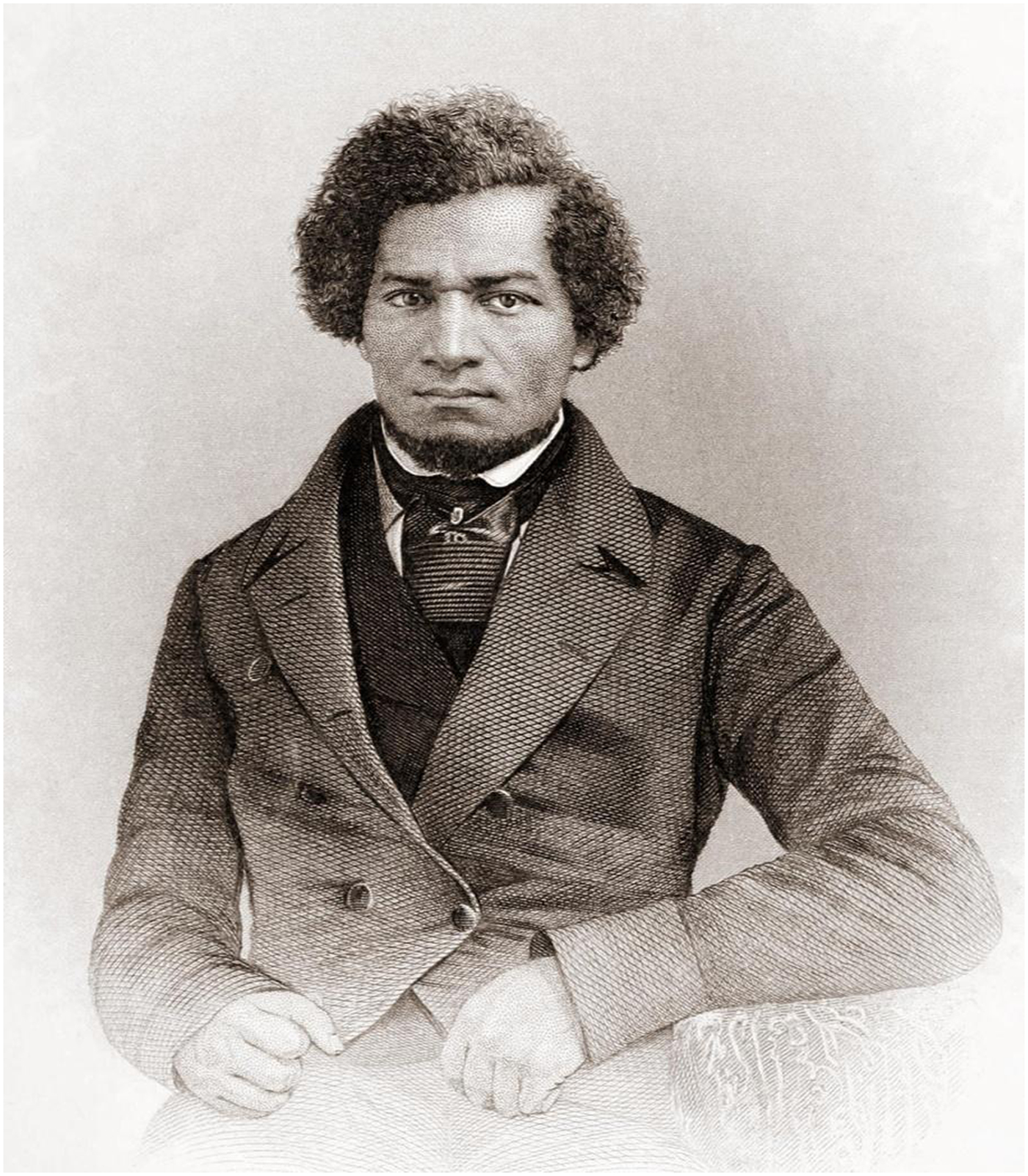

If Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) framed twentieth-century disputes over racial inequality,Footnote 74 Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) stirred nineteenth-century activism.Footnote 75 The case denying citizenship to persons of African descent inspired fervent abolitionist resistance.Footnote 76 Activists critiqued the case and the Fugitive Slave Law, and they deployed rights talk for moral suasion, for political and cultural mobilization, and to make legal claims.Footnote 77

Consider Frederick Douglass's 1860 speech arguing that the original Constitution did not, in fact, support slavery. Douglass reached this conclusion through an ingenious textual interpretation, one that rested in part on his reading of the preamble to the Constitution to achieve his moral and political purposes. “The Constitution[‘s] … language is “we the people,” he noted, “not we the white people.” Therefore, he “denied that the Constitution guarantees the right to hold property in man.”Footnote 78

William Lloyd Garrison, publisher of the Liberator and leader of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, shared Douglass’ anti-slavery purpose, but not his constitutional interpretation.Footnote 79 Douglass was to Garrison as Dr. King was to SNCC.

Garrison called the Constitution a “bloody” and “wicked” compact.Footnote 80 And in an 1854 Fourth of July rally—where he stood on a stage decorated with an inverted United States flag—Garrison lit a match to the Constitution (and the Fugitive Slave Law).Footnote 81

His dramatic display of contempt for the Constitution reflected the times, and presaged the Civil War to come.

Suffrage

Illustrating how protest movements beget movements, leaders of the National Woman Suffrage Association, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, organized a multifaceted suffrage strategy that borrowed some tactics from abolitionism.Footnote 82 The tactics included litigation, lobbying, and civil disobedience.Footnote 83 Perhaps most famously, Anthony voted illegally in the presidential election of 1872, and then gave an address during which she, echoing Frederick Douglass, cited the preamble to the Constitution to justify her action.Footnote 84

The preamble to the Constitution says: “[W]e, the people; not we, the white male citizens; nor yet we, the male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed the Union.”Footnote 85 Therefore, she argued, citizenship did not exclude women.

Despite the elegance of Anthony's speech, women only gained suffrage after the face of the Constitution itself changed in 1920, when states ratified the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution.Footnote 86

Women's Liberation

Then, in the twentieth century, proponents of “women's liberation” attacked sex discrimination that persisted in social life, politics, and the workplace despite the Nineteenth Amendment. In court, lawyers drew analogies to race discrimination—now constitutionally and statutorily proscribed. In the words of Serena Mayeri, women “reasoned from race,” and with considerable success.Footnote 87

And, in a replay of some of the dynamics in the civil rights movement, some women's liberation activists criticized the reliance on courts to do the cultural work of ending male domination. The Fourteenth Amendment demanded that women conform to the male norm, a version of equality that fell far short of liberation.Footnote 88 That type of argument would never destroy male supremacy—no more than a constitutional suit could destroy white supremacy.

Sounding like SNCC, feminist critics argued that true liberation demanded critiques not only of cultural norms, but also of economic structures. Conflict occurred as economically secure, middle-class reformers in the National Organization of Women (NOW) sought inclusion in the workplace, while working-class and poor women, many of them black and Hispanic, urged a focus on issues economic at their core.Footnote 89

Women's different priorities can be seen in the varieties of feminism that flowered: socialist feminists;Footnote 90 welfare rights activists led by Johnnie Tillman, a sharecropper's daughter, who hoped for a living wage that would enable women to avoid welfare;Footnote 91 black and Chicana feminists, who foregrounded intersectional oppression (based on race, ethnicity and class, sex, and sexuality);Footnote 92 feminists focused on reproductive rights and women's health;Footnote 93 women seeking to end male cultural dominance;Footnote 94—and always, women demanding greater employment opportunity, equal pay, and the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA).Footnote 95

Amid the ascent of the feminisms, the political opportunity structure changed. Richard Nixon—the voice of a silent majority premised on white identity and backlash to anti-war and civil rights activism—took office. Although Nixon did sign Title IX of the 1972 Education Amendments and endorsed the ERA,Footnote 96 he vetoed the first federal legislation providing comprehensive childcare assistance, denouncing it as “radical,” which I think was the point.Footnote 97 And then there was Watergate, Nixon's resignation, and the loss of faith in American institutions.Footnote 98

The Relationship Between Movements and Electoral Politics

The allusion to Nixon brings me to the relationship between protest movements and electoral politics. One of the most striking features of today's Resistance is its characterization as a millions-strong group laser-focused on defeating Trump. This is definitely a moment that the Democrats should be able to capitalize upon.

As a student of long resistance, I find myself given pause by the singular focus on electoral politics, much of which is media analysis but some of which reflects efforts by donors to funnel the energies of the Resistance into electoral politicsFootnote 99 to tame and constrain popular discontent. I suggest that the zero-sum dynamics of partisan politics is a strikingly narrow framework for analyzing both what is at stake and the value added by grassroots, popular movements.

Historically, many of these movements organized for change—in society and culture, as well as in law and public policy—while deliberately avoiding domination by the two parties.Footnote 100

The civil rights movement did collaborate with particular political figures—think Dr. King and President Lyndon Johnson—but only when doing so suited the movement.Footnote 101 Through discussions with President Johnson over the need for economic redress for blacks and for all Americans suffering economic hardship, Dr. King helped secure the Economic Opportunity Act (EOA) of 1964, the legislative centerpiece of the War on Poverty.Footnote 102 Some of the War on Poverty programs did, in fact, help to disestablish the racial state that New Deal social programs had kept firmly intact.Footnote 103 In the Deep South, movement allies leveraged the concept of community action embedded in the EOA to benefit tenant farmers, manual laborers, and other hardworking people, attaining grants for housing and education.Footnote 104 As Gavin Wright, the professor of economic history showed in his book, Sharing the Prize, these grants made a difference. Between 1959 and 1978, the Southern black rural poverty rate declined from 77.7% to 37.2%.Footnote 105

Nevertheless, conceptually, President Johnson—who championed a hand-up rather than a handout—eschewed Dr. King's idea of a minimum income. Hence, the poverty programs did not go nearly as far as Dr. King and others had wanted.Footnote 106

For this reason, SNCC and Ella Baker—grassroots proponents of an antipoverty vision of human rights—thought of Dr. King's alliance with President Johnson as a “malignant kinship.”Footnote 107 The students disdained the strategic political alliances that yielded compromise legislation. People in local communities—who were bereft of basic daily needs—could not afford compromise, the group argued. Harshly criticizing the Democratic Party, SNCC pushed for a more progressive sociolegal agenda, one that empowered local people.Footnote 108

SNCC—which had witnessed squalor and hunger, dilapidated houses, and crumbling schools in the North and South—kept pushing for more. Some in SNCC, like Julian Bond and John Lewis, transitioned from “protest to politics,” as Bayard Rustin suggested.Footnote 109 They sought to become the elected officials and party leaders they had hoped for. Civil rights lawyers filed suits attacking exclusion from the state and local political apparatus.Footnote 110 In short, activists took democracy into their own hands.

The Long Political Resistance

SNCC was hardly alone. The women's liberation movement included a variety of organizations focused on different objectives—none defined by a political party. The tradition of political independence even occurred when women attained political office and nominally represented the system.

Shirley Chisholm won a seat in Congress as a Democrat, but famously proclaimed herself Unbought and Unbossed.Footnote 111 The Brooklyn Congresswoman refused Democrats’ plea to be a “good soldier” and accept an assignment to the House Agricultural Committee and subcommittees focused on “rural development and forestry.”Footnote 112 It was “hard to imagine,” she protested, “an assignment less relevant to her background or to her predominantly black and Puerto Rican district in Brooklyn, where many residents were unemployed, hungry, and badly housed.”Footnote 113 Chisholm won that battle, and later she critiqued the entire political system in still relevant terms: ““It is incomprehensible to me, the fear that can affect men in political offices. It is shocking the way they submit to forces they know are wrong and fail to stand up for what they believe. Can their jobs be so important to them, their prestige, their power, their privileges…that they will cooperate in the degradation of society just to hang onto those jobs?… Our representative democracy is not working.”Footnote 114

Also think of Bella Abzug, another New York Congresswoman, known for denouncing her colleagues as a privileged elite out of touch with America. She, too, refused to go along with political compromises just to get along.Footnote 115 In 1978, President Jimmy Carter fired Abzug from her position as co-chairwoman of the National Advisory Committee for Women; the firing stemmed from Carter and Abzug's “stormy relationship,” illustrated by incidents such as Abzug's giving a “lecture” to the president on the committee's proper role, and her cancellation of a meeting with the White House because it was limited to 15 minutes.Footnote 116

And so we see that the tradition of political independence—like the resistance itself—is long. Whether abolitionists, woman suffrage advocates, or welfare rights activists, those in progressive change movements have gained influence by disrupting politics as usual—not by aligning lockstep with electoral parties. Activists accepted the support of parties, but demanded the autonomy necessary to define and control their missions, create their own narratives, and maintain enough distance to critique the overarching structure of the system—which long ago they called rigged. That is how grassroots social movements—as opposed to interest or lobbying groups—typically function, in full recognition that the arena of national electoral politics is not the place to expect the full realization of a movement's agenda. The emphasis here is on full.

Years after the election of a critical mass of women and minorities, political scientists confirmed how difficult it is for them to translate descriptive into substantive representation, truly representing the interests of constituents.Footnote 117 Moreover, the decades-long contest over gerrymandering has seriously fettered their power, and some scholars fear, representative democracy itself.Footnote 118

Resistance Today: The Tea Party Analogy

My analysis of the relationship between protest movements and formal politics calls into question much of recent commentary drawing connections between the present Resistance and the Tea Party.

The Tea Party is a model for the current Resistance, it is said, because it translated popular dissatisfaction with Washington into policy priorities.Footnote 119 The Tea Party was definitely effective in many ways. One can see echoes in the Tea Party of some of the tactics and narrative strategies that I associated with the civil rights movement.Footnote 120 The Tea Partiers wrapped themselves in the flag and repeatedly invoked legalistic concepts, including the aspirational language of We the People, liberty, and equality.Footnote 121 And the name—Tea Party—is evocative. Yet, even setting aside the white racial identity politics embedded in many Tea Party critiques of the ACA, the analogy strikes me as problematic.Footnote 122

The political scientist Theda Skocpol has shown that, contrary to media mischaracterizations, the Tea Party was not merely a popular insurgency.Footnote 123 In the wake of electoral defeat in 2008, Republican political operatives, wealthy businessmen and foundations, and media elites such as Glenn Beck manufactured a backlash against Obama, the ACA, and new social programs.Footnote 124 The concerted effort exploited racial resentment and anxiety about handouts to the “undeserving poor,” to use Martin Gilens’ term,Footnote 125 among a minority of voters, disproportionately male, older, and white.

Thus, the Tea Party is best understood as an anti-tax, anti-regulation mobilization by corporations and foundations—complete with paid operatives, staged demonstrations and a disinformation campaign.Footnote 126 It was not really a grassroots revolt, although the grassroots were mobilized in support of backers’ policy priorities.Footnote 127 The Tea Party mostly represents the manipulation of democracy, not its manifestation.

What, then, is there in the Tea Party for the anti-Trump Resistance to replicate? The suggestion would make sense if the interests of the Resistance and some political party aligned—which is not a judgment for me to make. Nevertheless, given the deep policy divisions on the Left seen in the run-up to the last election, interest convergence seems doubtful.Footnote 128 Perhaps the analogy does make sense to the extent that it suggests the need for grassroots state and local organizing. A better analogy for the Resistance are the kinds of protest movements I have described here—ones that pushed and pulled the Democratic Party closer to its agenda.

Historical Memory

I will conclude with some thoughts about historical memory—views generated, in part, by the wide dissemination of the idea that contemporary protest groups and normal political institutions are of a piece. That very idea suggests selective memory: one cannot seriously entertain that thought and be aware of the points that I just made about progressive social movements’ historic political independence.

I also have made the point that, although we remember movements in ways that emphasize distinctiveness, it is vitally important to appreciate the connections among them—particularly the economic thread. One cannot really understand the civil rights struggles without a deep appreciation of the labor movements and women's liberation. The shared agenda of the great twentieth-century social movements to remake the social contract—the push for greater fairness—is an overarching theme of these movements, and that aspiration still resonates in our time.

As we, as scholars and citizens, seek a more synthetic and holistic understanding of history, we must make the cultural backlash to progressive social movements a more prominent part of our discussion and analysis. We have not sufficiently documented or analyzed right-wing protest movements. Our scholarship and our collective memory do encompass symbols of hate and white resistance such as Bull Connor,Footnote 129 George Wallace,Footnote 130 and Orval Faubus;Footnote 131 and these men are easy to caricature, compartmentalize, or dismiss into the dustbins of history.

I refer, instead, to studies of everyday people and institutions, the places where cultures of white resistance persisted and proliferated despite the civil rights movement and against the backdrop of a global war on terror—the coming of age period for the young white supremacists on the streets of Charlottesville.Footnote 132 We have not imagined an effective language for describing and explaining these phenomena.

The effects of this selective memory left journalists and some scholars surprised by the open white supremacy we have witnessed in this country in recent months.Footnote 133 It leads students supposedly protesting fascism to shout down the supposed fascists, totally unaware of the irony.Footnote 134

We would be less surprised by these currents if we paid sufficient attention to the scholarship that does exist on right-wing social movements. Consider Jason Sokol's exploration of the loss of racial status and its cultural meaning for white Southerners during the age of civil rights, aptly named: There Goes My Everything, a book filled with stories about change, as well as continuity, in social relations after the civil rights resolution.Footnote 135

Nancy MacLean's Democracy in Chains also offers vital insights. MacLean locates the roots of certain strands of libertarian policies touted by elites in massive resistance to Brown v. Board of Education; these same libertarians, led by the Koch brothers, have captured much of our government, she argues.Footnote 136

Finally, we, whether in memory or in scholarship, have not fully come to terms with forms of the protest against the wretched life conditions experienced by poor men, women, and children, particularly people of color, whether as seen in the Black Power movement or in the Movement for Black Lives. This is true, even though, for years now, scholars such as Peniel Joseph,Footnote 137 Matthew Countryman,Footnote 138 Robert Self,Footnote 139 and othersFootnote 140 have explained that Black Power, despite the narrowness evoked by the name, related to subjects relevant to any other history of the post-industrial state: to questions about jobs, taxes, schools, and policing.

A similar claim can be made about the Movement for Black Lives, which is not covered with the same interest, depth, or empathy as the part of the Resistance focused on electoral politics, or mentioned in the same voice as the historic struggles for equality that we now concede rooted out long-standing oppression in our society. Nevertheless, the connections to the long struggle for black freedom are clear. Consider this passage from Courage to Dissent.

Despite persistent complaints by black citizens from all walks of life about unlawful arrest and police brutality, local judges invariably sided with white officers. A judge dismissed charges against one officer accused of beating a 21-year old black man, Earl Sands, with a black jack and an iron link chain. The officer, who was cruising in his police car, claimed that Mr. Sands had disturbed the peace on Sands’ walk from one house to another—two doors down—at 2 am on August 7, 1940. The officer alleged that Sands had resisted arrest; the young man proclaimed his innocence and begged to go home to his wife and child. In dismissing the complaint against the white officer, Judge Robert Carpenter commended him, saying, ‘being a police officer is no easy job.’Footnote 141

That passage, in broad outlines, could have been written about events in 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000, last year, or last month.

In continuing a long struggle against excessive use of force, the Movement for Black Lives makes a demand for the most basic human right of all, bodily integrity—along with a plea for a fair share of resources and investment in predominantly poor, minority communities.

Some of the movement's rhetoric sounds remarkably like the moral claims-making and cultural critique that we associate with Dr. King and SNCC. One wonders why, in a nation that now valorizes Dr. King, so many still cannot hear the claims of Black Lives Matter.

Conclusion

Thus, I conclude that what looks new must be seen in light of old and enduring dilemmas deeply rooted in social, political, and economic conflict. The interrelated conflicts bring to mind Dr. King's indictment, so many years ago, of the triple evils of “poverty, racism and militarism.”Footnote 142 The present conflicts hearken to foundational struggles over how to reconcile liberty, equality, and property rights.

Only now we debate the nature of a social contract in the wake of deindustrialization, deregulation, financial crisis, perpetual war, Google and Amazon, Twitter and Facebook, and yes, reality television, the cult of celebrity, and what it has wrought.