Despite good evidence of efficacy in depressive disorders (UK ECT Review Group, 2003), electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) remains controversial (Reference Rose, Wykes and LeeseRose et al, 2003). This is highlighted in the NICE guidance (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2003). The use of ECT in incapacitated patients is probably an even more contentious issue. It is reported that the practice of detaining mentally incapable and compliant patients for treatment of their mental disorder is widespread (Reference JonesJones, 2004). Many clinicians may choose statutory rather than common law because of a perception that because ECT is considered different from other common forms of treatment for mental disorder, there should be statutory safeguards when it is administered to incapacitated patients (Reference RobinsonRobinson, 2003). There is no case law that addresses the issue of ECT in such patients.

Vignette 1

A 30-year-old lady with resistant depression was admitted informally because of a high suicide risk. In the past, she has made several suicide attempts and has ended up on the intensive care unit after a serious overdose. Various pharmacological treatments have all been ineffective so far, but she has responded well to ECT previously. You judge that ECT is the only realistic option. She understands your rationale for recommending ECT but nevertheless refuses to have it.

Vignette 2

A 68-year-old man was admitted informally following the death of his wife 2 months ago. He has become severely depressed and withdrawn, with significant weight loss. He is barely communicative, refusing to eat or drink and take his antidepressant despite encouragement from staff. You have decided to proceed with ECT as you consider his condition to be critical. The next-of-kin is in agreement with the treatment plan. He does not appear to object to a pre-ECT work-up, i.e. he has allowed staff to take his blood, has had an ECG and a chest X-ray. He appears to passively accept whatever treatment is proposed. However, you believe that despite discussions, he does not understand what ECT really entails.

Vignette 3

A 45-year-old man with a history of bipolar affective disorder was admitted informally following a depressive relapse. Despite pharmacological treatment, he has become increasingly deluded and paranoid and his behaviour extremely risky. As he has responded well to ECT in the past and you judge his condition as potentially life-threatening, you decide to proceed with ECT. During discussion of the treatment plan with him, he thanks you for offering ECT. He tells you that he deserves it and the only reason he needs ECT is because he has committed unforgivable sins and this will get rid of all evils inside him.

The aim of this study was to examine what stance senior psychiatrists will take in practice, in view of available opinions, such as that provided by the Mental Health Act Commission (2003) and the ninth edition of the Mental Health Act Manual (Reference JonesJones, 2004). We also sought the legal opinion of one medical defence organisation.

Method

In September 2004, a questionnaire was sent to consultant psychiatrists working within the Wessex rotation. They were identified from a list of educational supervisors provided by the postgraduate department. Those who did not respond were sent a reminder several weeks later. Child and adolescent psychiatrists were excluded from the survey, as they do not commonly use ECT.

Participants were presented with three vignettes and asked how they would proceed in each case. Vignette 1 refers to a seemingly capacitated adult who refuses to have ECT (see below) whereas vignettes 2 and 3 both refer to incapacitated and compliant patients (one passively compliant and one complying because of his delusional beliefs). Clinicians had to choose one of three options:

-

(a) proceed under common law;

-

(b) first obtain a second opinion from a colleague and if they agree proceed under common law;

-

(c) make a recommendation for detention under a Section of the Mental Health Act (MHA) and if the patient is detained, seek a second opinion in accordance with Section 58 of the MHA 1983.

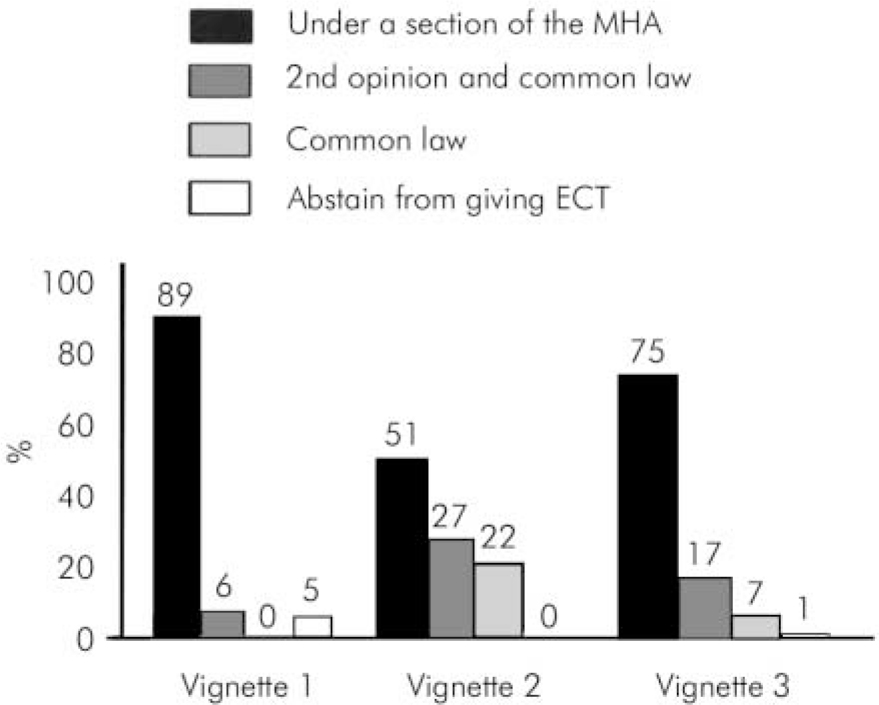

Fig. 1. How consultant psychiatrists would proceed when giving electroconvulsive therapy under three clinical scenarios. MHA, Mental Health Act 1983.

The participants were invited to add comments if they wished to do so.

Results

A total of 70 consultant psychiatrists were identified. Fifty-six returned their questionnaire giving a response rate of 79%. The majority of respondents were general adult psychiatrists (58%), followed by old age (26%), forensic (5%), learning disability (5%), substance misuse (4%) and liaison psychiatrists (2%). Of respondents, 29% had been practising as a consultant for 5 years or less, 22% between 6 and 10 years and 37% for more than 10 years. Of these, 12% did not specify the number of years worked as a consultant.

For vignette 1, the majority (89%) would proceed under a Section of the MHA, with 6% opting for common law only after obtaining a second opinion from a colleague and 5% not contemplating ECT. For vignette 2, 51% of clinicians would proceed under the MHA and 49% would proceed under common law (27% after seeking a second opinion). For vignette 3, 75% would use the MHA and 24% common law (17% after seeking a second opinion). The remaining 1% decided against giving ECT. These responses are summarised in Fig. 1.

One interesting observation was that recently appointed consultants seemed less inclined to use the MHA, especially with incapacitated and compliant patients, than more experienced colleagues. For example, in vignette 2 only 37% of those with less than 6 years’ consultant experience would use the MHA compared with 58% of those with between 6 and 10 years experience and 50% of those with greater than 10 years experience. In vignette 3, 56% of those with less than 6 years experience would use the MHA compared with 91% and 80% of the more experienced groups, respectively. Although the numbers are small, this trend is apparent for all three vignettes.

Numerous comments were received demonstrating a wide range of differing opinions, which were strongly expressed. Most of these comments focused on the requirement to protect patients’ civil liberties. There were few comments suggesting the existence of specific protocols within individual trusts.

Discussion

Our survey took place in a geographically defined area of southern England. It shows that the overwhelming majority of consultant psychiatrists agree that mentally capable and refusing adults who require treatment with ECT should be detained under the MHA and a second opinion sought from the MHA Commission.

A few consultants were opposed to using ECT in vignette 1, because this would mean overriding the patient's autonomy. This decision also appears to have been influenced by their personal attitudes to ECT. Rethink is opposed to the use of ECT in capacitated and non-consenting patients (Rethink, 2004), including those detained under the MHA, unless they have a life-threatening condition. The proposed mental health legislation would allow competent detained patients to refuse ECT, except when expressly authorised by a tribunal or where it constitutes emergency treatment.

Opinion was divided among psychiatrists when dealing with incapacitated and compliant patients, with almost equal numbers opting for the MHA or common law (vignette 2). However, more consultants (75%) were in favour of the MHA in vignette 3 where a man agrees to ECT on the basis of his delusions. Psychiatrists may feel more comfortable with using the MHA when someone is demonstrating clear psychotic symptoms.

There has been ongoing debate as to whether mentally incapacitated but compliant patients should be detained in order to administer ECT lawfully. The General Medical Council guidance on incapacitated patients (General Medical Council, 1998) states that if they comply, treatment may be given if in their best interests. However, if they do not comply, they may be compulsorily treated under the MHA. The more recent MHA Commission view, however, is that detaining such patients for the purpose of ECT may be unnecessary and therefore may constitute unlawful use of the MHA (Mental Health Act Commission, 2003). The ninth edition of the Mental Health Act Manual (Reference JonesJones, 2004) expressed the view that under common law ECT can be given lawfully to the incapacitated patient without consent provided it satisfies the best interests test. He added that, ‘it is neither necessary nor legally proper to make an application in respect of a patient who is not attempting to leave hospital and whose treatment is authorised under common law’.

In such cases, the Special Committee on ECT (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2005) has issued some guidance on good practice such as ‘ attempts should be made to improve the patient's clinical condition so he or she is able to consent to the treatment proposed’, the need to discuss with family and carers and to seek a second opinion from a consultant colleague. The patient should be reassessed following each treatment with regard to both capacity and compliance, and if remains compliant, a further treatment can be given. Advice from the Medical Defence Union suggests that in vignettes 2 and 3, treatment can be justified under common law, although it is good practice to discuss with relatives and get the opinion of a colleague.

The ruling in the Bournewood case ( R v. Bournewood Community and Mental Health NHS Trust, 1998) meant that mentally incapacitated patients who were compliant with admission to hospital could be admitted under common law. However, in the recent Bournewood judgement ( HL v. UK, 2004) of the European Court of Human Rights, HL was found to be deprived of his liberty, which was unlawful. The implication is that incapacitated patients who are under constant supervision and control of staff and not free to leave, would now be subject to a MHA assessment.

This survey, which was conducted prior to the release of the European Court of Human Rights judgment ( HL v. UK, 2004), reveals both a lack of consensus among consultants and a disparity between clinical practice and available guidance. Despite this guidance, more than half of the senior psychiatrists surveyed instinctively preferred to use the MHA when treating incapacitated but compliant patients with ECT. It appears from comments made that this is because clinicians wish to do everything possible to provide the best legal safeguards for patients, to ensure protection from possible abuse. It will be interesting to see what impact the latest Bournewood judgment has on clinical practice. Although this ruling was concerned with consent to admission rather than treatment, it is likely that there would be implications for those patients described in vignettes 2 and 3. We believe the effects of this will be that more incapacitated but compliant patients will be treated under the MHA, which in any case, is in line with the current practice of many clinicians.

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all consultant psychiatrists who took part in this survey.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.