Introduction

Organizations are increasingly operating in multicultural and multinational contexts (Tsui, Nifadkar, & Ou, Reference Tsui, Nifadkar and Ou2007). In 21st century, the metaphor of a ‘flat world’ (Friedman, Reference Friedman2005) comprehensively represents the contemporary business world. Furthermore, team creativity is very important for organizational performance and their survival in the global market (Shin, Kim, Lee, & Bian, Reference Shin, Kim, Lee and Bian2012). Therefore, many firms recruit people with specialized expertise and creative potentials, beyond national borders, to develop unique and novel products (Hinds, Liu, & Lyon, Reference Hinds, Liu and Lyon2011). Hence, the need to examine the relationship between team diversity and team creativity is becoming essential more than ever (Jackson, Joshi, & Erhard, Reference Jackson, Joshi and Erhard2003). However, team diversity is a double-edged sword and has been a significant challenge in contemporary organizations (Chi, Huang, & Lin, Reference Chi, Huang and Lin2009). Despite that comprehensive attention has devoted to diversity–creativity relationship, there is still a relative dearth of exploring mechanism between them (Hoegl, Parboteeah, & Muethel, Reference Hoegl, Parboteeah and Muethel2012). Harrison, Price, Gavin, and Florey (Reference Harrison, Price, Gavin and Florey2002) and Mannix and Neale (Reference Mannix and Neale2005) have concluded that demographic (surface level) diversity tends to be more likely to have negative effects and psychological/functional (deep level) diversity mostly positively related to outcomes. Relatively, two questions remained unanswered: how organizations can overcome the negative effect of surface-level diversity and leverage the positive effect of deep-level diversity in terms of team creativity?

Although researchers have investigate the influence of team diversity, both surface and deep-level diversity, on team creativity (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Price, Gavin and Florey2002; Harrison & Klein, Reference Harrison and Klein2007; van Knippenberg & Schippers, Reference Van Knippenberg and Schippers2007; Hoever, van Knippenberg, van Ginkel, & Barkema, Reference Hoever, van Knippenberg, van Ginkel and Barkema2012; Shin et al., Reference Shin, Kim, Lee and Bian2012), but the process of diversity–creativity relationship has been, relatively, overlooked. Therefore, researchers have called for investigating the mechanisms and conditions under which organizations can harvest the positive outcomes of team diversity (Schippers, Den Hartog, Koopman, & Wienk, Reference Schippers, Den Hartog, Koopman and Wienk2003; van Knippenberg & Schippers, Reference Van Knippenberg and Schippers2007; Joshi & Roh, Reference Joshi and Roh2009; Shin et al., Reference Shin, Kim, Lee and Bian2012). Knowledge and information sharing of diverse team members value diversity (Tang & Naumann, Reference Tang and Naumann2016) that may lead to team creativity (Cummings, Reference Cummings2004; Tang & Naumann, Reference Tang and Naumann2016). Mannix and Neale (Reference Mannix and Neale2005) demonstrate that carefully examining the mediating mechanism could help to clarify the process between diversity and outcomes. Therefore, how team knowledge sharing mediates the relationship between team diversity (surface level and deep level) and team creativity?

The purpose of this study is to explore the conditions that elevate the positive and dilute the negative effects of team diversity on team creativity. Moreover, we examine the underlying mechanism between team diversity and creativity that explains how team diversity leads to creativity. Team members’ perception of team diversity and team climate has important effect on their behavior and outcomes (Schneider & Reichers, Reference Schneider and Reichers1983; Anderson & West, Reference Anderson and West1998). Diversity effect relies on perception (Lawrence, Reference Lawrence1997), and it reflects the psychological importance and subjective impact of actual diversity. Moreover, Nishii and Mayer (Reference Nishii and Mayer2009) have suggested that an individual feels self-identity and psychological empowerment when s/he perceives inclusion in a diverse group. An inclusion climate makes diverse team members feel less discrimination and facilitates their interpersonal relationship and knowledge sharing. Therefore, team members’ perception of team diversity and climate influence their behavior and outcomes.

This study contributes to team diversity and team creativity literature in three ways. First, we investigate and test a model that integrates perceived team diversity and team creativity in cross-national research teams. It provides deep insight into distinct effects of team diversity on team knowledge sharing and creativity. Second, we examine the knowledge sharing as intervening mechanism, which helps to understand the process between team diversity and creativity. Third, we empirically explore the moderating effect of team inclusive climate factor between team diversity and knowledge sharing, which enhances the positive and diminishes the negative effects of team diversity.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Team diversity and team creativity

Diversity has been defined in several ways; most researchers focused on the effects of diversity, which can result from any characteristic people use to tell themselves that another person is different (Williams & O’Reilly, Reference Williams and O’Reilly1998; van Knippenberg, De Dreu, & Homan, Reference Van Knippenberg, De Dreu and Homan2004). In our study team diversity is defined as the differences among members of an interdependent work group with respect to specific demographic and psychological attributes (Jackson, Joshi, & Erhard, Reference Jackson, Joshi and Erhard2003; Joshi & Roh, Reference Joshi and Roh2009). The existing studies predict higher team creativity when team members are different in terms of task-relevant perspectives and knowledge (Hoever et al., Reference Hoever, van Knippenberg, van Ginkel and Barkema2012). Therefore, work teams can promote creativity through effective cross-fertilization of ideas that are conducive to better decision making and innovation (Shin & Zhou, Reference Shin and Zhou2007; Chi, Huang, & Lin, Reference Chi, Huang and Lin2009).

Research has concluded that different types of diversity may have different effects on the outcomes (Williams & O’Reilly, Reference Williams and O’Reilly1998). To better understand how diversity influences teams, it is necessary to understand the different types of diversity (Dahlin, Weingart, & Hinds, Reference Dahlin, Weingart and Hinds2005). Harrison, Price, and Bell (Reference Harrison, Price and Bell1998) categorized work group diversity into surface-level diversity and deep-level diversity. Surface-level diversity refers to the extent to which a team is heterogeneous on overt characteristics such as gender, age, physical features, and ethnicity. Deep-level diversity refers to heterogeneity among team members’ psychological characteristics such as attitudes, personality, beliefs, and values (Harrison, Price, & Bell, Reference Harrison, Price and Bell1998; Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Price, Gavin and Florey2002).

We emphasize on team members’ perception of diversity (surface level and deep level) because it represents their psychological meaning and importance to diversity. Although Tsui, Egan, and O’Reilly (Reference Tsui, Egan and O’Reilly1992) and Williams and O’Reilly (Reference Williams and O’Reilly1998) have focused to measure demographic variables (e.g., age, gender, and race) objectively (index), Harrison et al. (Reference Harrison, Price, Gavin and Florey2002) suggest that objective and perceived measures of team diversity are significant correlated. Besides, Shemla, Meyer, Greer, and Jehn (Reference Shemla, Meyer, Greer and Jehn2014) argued that focus on objective diversity has challenged and a growing number of researchers are focusing on perceived diversity because people react to their perception of reality rather than reality per se (Hobman, Bordia, & Gallois, Reference Hobman, Bordia and Gallois2004). Furthermore, Shemla et al. suggested that ‘perceived diversity do not only provide an additional set of insights about group composition, it may even offer a superior substitute to objective diversity measures’ (Reference Shemla, Meyer, Greer and Jehn2014: 13). Therefore, we consider perceived team surface-level diversity as the extent of perception about demographic (age, gender, race, and nationality) heterogeneity of team members. Whereas we refer perceived team deep-level diversity as the extent of perception about psychological (attitude, personality, and values) heterogeneity of team members (Joshi & Roh, Reference Joshi and Roh2009).

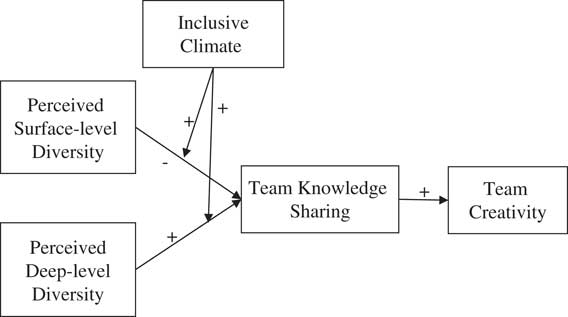

Figure 1 shows the theoretical framework of this study.

Figure 1 Research framework

Team creativity is defined as the joint novelty and usefulness of ideas generated or developed by a group of people (Amabile, Conti, Coon, Lazenby, & Herron, Reference Amabile, Conti, Coon, Lazenby and Herron1996). The relationship between team diversity and creativity has been studied widely; however, relationship was contingent on type of diversity, team setting, and other contextual factors (Hoever et al., Reference Hoever, van Knippenberg, van Ginkel and Barkema2012; Huang, Po-An Hsieh, & He, Reference Huang, Po-An Hsieh and He2014). Individual with different knowledge, skills, perspectives, and thinking styles can be hotbeds of team creativity (Shin et al., Reference Shin, Kim, Lee and Bian2012). The members of cross-nation team possess diverse knowledge, skills, and expertise, which demonstrate value for team creativity. If the cross-national team members effectively cross-fertilize their ideas and knowledge, they will promote team creativity (Shin & Zhou, Reference Shin and Zhou2007). Failing to effectively manage team diversity could lead to functional or relational conflict (Jehn, Northcraft, & Neale, Reference James, Demaree and Wolf1999). Thus, if the team members suffer from high level of task conflict or relational conflict, they will be less likely to engage in process efficiency or generating novel and useful ideas (Mannix & Neale, Reference Mannix and Neale2005; Seong & Choi, Reference Seong and Choi2014).

Drawing on social categorization and information-processing theories, Mannix and Neale (Reference Mannix and Neale2005) argued that it is almost impossible to understand the diversity-process-outcome link without integrating theoretical perspective, clear context, and team’s purpose. Dahlin, Weingart, and Hinds (Reference Dahlin, Weingart and Hinds2005) proposed that effects of surface-level differences are better explained by social categorization theory, whereas deep-level differences are better explained by information-processing theories. Based on the arguments of Mannix and Neale (Reference Mannix and Neale2005), we expect that surface-level diversity negatively relates to team creativity and deep-level diversity positively relates to team creativity.

The diversity literature demonstrates, people in a diverse group differentiate themselves according to their demographic attributes and characteristics that negatively influence group processes and outcomes (Hogg & Terry, Reference Hogg and Terry2000). Furthermore, Dahlin, Weingart, and Hinds (Reference Dahlin, Weingart and Hinds2005) suggested that surface-level diversity is likely to trigger social categorization processes that prevent team members from exploiting the potential benefits of their heterogeneous knowledge, skills, and experiences. The fragmented overt differences among team members will impede social integration and less knowledge and information sharing, which result fewer novel and useful ideas. Creativity is the generation of novel and useful ideas in any domain (Amabile et al., Reference Amabile, Conti, Coon, Lazenby and Herron1996). Therefore, for team to be creative, it is necessary for team members to share and integrate diverse knowledge and skills. Perceived overt differences engender social categorization among cross-national team members that hamper social interaction and restrain knowledge sharing, which impede team creativity. Therefore, we hypothesize

Hypothesis 1a: Perceived surface-level diversity in a cross-national team is negatively related to team creativity.

Harrison et al. (Reference Harrison, Price, Gavin and Florey2002) demonstrated that individuals feel, relatively, comfortable to interact with others who have symmetrical psychological characteristics because that interaction reinforces their fundamental values and beliefs. The deep-level diversity characteristics (values, attitudes, knowledge, experience, and personality) represent psychological and cognitive diversity among the team members. The cognitive diversity between the team members engenders problem solving behavior and creativity (Harrison & Klein, Reference Harrison and Klein2007; Shin et al., Reference Shin, Kim, Lee and Bian2012). Variance in team members’ knowledge, skills, and experience that diversity brings, according to information and decision-making theories, promotes creativity (Tziner & Eden, Reference Tziner and Eden1985). Also, members of a diverse team could have greater access to information networks outside their team (Ancona & Caldwell, Reference Ancona and Caldwell1992) that may lead to team creativity. In this way, deep-level diversity characteristics are positively associated with team creativity. The psychological approach demonstrates that a team composition based on individuals’ psychological capital (Post, Reference Post2012) promotes creativity, but connecting thinking integration is necessary. Hence, a diverse team’s functioning (Perry-Smith & Shalley, Reference Perry-Smith and Shalley2014), and knowledge variety leverage team creativity and problem solving (Hoever et al., Reference Hoever, van Knippenberg, van Ginkel and Barkema2012). Thus, we hypothesize

Hypothesis 1b: Perceived deep-level diversity in a cross-national team is positively related to team creativity.

Team diversity and team knowledge sharing

Knowledge sharing is defined as, the exchange/provision of information and know-how to help and collaborate with others to solve problems and develop new ideas (Cummings, Reference Cummings2004). Knowledge sharing occurs through communication and information exchange between individuals. Organizations attempt to remove barriers and promote knowledge sharing among team members to achieve creative performance, which helps to accelerate group processes and creative ideas (Hu & Randel, Reference Hu and Randel2014). The diversity-knowledge sharing relationship is contingent on the form of diversity and team members’ perspective on the relationship. Previous studies have found that surface-level diversity is negatively associated with team functioning (Mohammed & Angell, Reference Mohammed and Angell2004; Casper, Wayne, & Manegold, Reference Casper, Wayne and Manegold2013). For instance, drawing from social identity and social categorization theory (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1978), Harrison et al. (Reference Harrison, Price, Gavin and Florey2002) suggested that team members differentiate themselves on the basis of overt demographic characteristics that result in less information sharing among diverse team members (Williams & O’Reilly, Reference Williams and O’Reilly1998; Horwitz & Horwitz, Reference Horwitz and Horwitz2007). Based on the arguments above, we hypothesize

Hypothesis 2a: Perceived surface-level diversity in a cross-national team is negatively related to team knowledge sharing.

Hu and Randel (Reference Hu and Randel2014) found that social capital, team members’ diverse knowledge and integration, is the effective source of knowledge sharing among team members. Cross-national research teams, investigated in this study, have a collaborative work structure and an interdependent task nature. It provides them information about other members’ knowledge and values that they can share to complete team task. The diverse knowledge of team members helps develop alternative solutions and resists ‘groupthink’ in decision processes (Joshi & Roh, Reference Joshi and Roh2009). Diverse team members exhibit high knowledge sharing when they have high learning motive and focus less on their social identity (Lin, Reference Lin2007; Lauring & Selmer, Reference Lauring and Selmer2012). Deep-level diversity concerns with team members’ knowledge, education, and experience, therefore according to information and decision-making perspective deep-level diversity could positively influence team knowledge sharing (Bell & Berry, Reference Bell and Berry2007; Shin et al., Reference Shin, Kim, Lee and Bian2012). Hence, diversity in deeply embedded factors encourages knowledge sharing. We thus propose

Hypothesis 2b: Perceived deep-level diversity in a cross-national team is positively related to team knowledge sharing.

Team knowledge sharing and team creativity

Knowledge sharing is referred as provision or exchange of ideas and information (Cummings, Reference Cummings2004). Researchers use knowledge sharing among diverse team members to predict team creativity (Hu & Randel, Reference Hu and Randel2014) because knowledge diversity and nonredundant information significantly affect creativity (Hansen, Reference Hansen2002; Shin et al., Reference Shin, Kim, Lee and Bian2012). Therefore, diverse team members’ knowledge sharing can elicit new combinations of ideas and insights (Cummings, Reference Cummings2004), which lead to team creativity. In general, knowledge sharing is one of the fundamental means through which team members can contribute to knowledge applications, innovation, and creativity (Wang & Noe, Reference Wang and Noe2010). Literature has suggested that knowledge sharing enhances creativity and innovation capability (Tsai, Reference Tsai2001). Furthermore, team creativity is also contingent on skills, knowledge, and cognitive diversity of team members (Shin et al., Reference Shin, Kim, Lee and Bian2012; Perry-Smith & Shalley, Reference Perry-Smith and Shalley2014). Researchers recognize the fact that knowledge sharing is crucial for knowledge creation (Tsai, Reference Tsai2001; Srivastava, Bartol, & Locke, Reference Srivastava, Bartol and Locke2006). Therefore, we hypothesize

Hypothesis 3: Team knowledge sharing in a cross-national team is positively related to team creativity.

The mediating role of team knowledge sharing

Knowledge sharing explains the relationship between diversity and creativity (Hu & Randel, Reference Hu and Randel2014). The social categorization perspective suggests that individuals in a diverse group differentiate themselves according to their demographic attributes and characteristics (Hogg & Terry, Reference Hogg and Terry2000) and therefore team members would be less likely to involve or engage in knowledge sharing. When knowledge sharing is rare, diverse team member may not be able to develop novel and unique solutions to problems. In this way, knowledge sharing mediates the relationship between surface-level diversity and team creativity. Thus, we hypothesize

Hypothesis 4a: Team knowledge sharing mediates the relationship between perceived surface-level diversity and team creativity.

However, it has been demonstrated that a diverse team with collective goals outperforms a homogeneous team because diverse team members hold broader range of, nonredundant, task-relevant knowledge, skills, and abilities (Williams & O’Reilly, Reference Williams and O’Reilly1998). This strengthens the argument that deep-level diversity triggers new thoughts and novel ideas. As argued in the literature, cognitive diversity (deep-level diversity) is positively related to creativity (Shin et al., Reference Shin, Kim, Lee and Bian2012). The new thoughts and novel ideas will lead to team creativity, when they are shared with other teammates. Therefore, sharing new knowledge and information leads to team creativity. Huang, Po-An Hsieh, and He (Reference Huang, Po-An Hsieh and He2014) have identified knowledge sharing as the intervening mechanism in the diversity–creativity relationship. The value diversity view point (Ely & Thomas, Reference Ely and Thomas2001) acknowledges the mediating role of knowledge sharing between diversity and creativity (Lauring & Selmer, Reference Lauring and Selmer2012). Therefore, we recognize knowledge sharing as an intervening mechanism in deep-level diversity and team creativity:

Hypothesis 4b: Team knowledge sharing mediates the relationship between perceived deep-level diversity and team creativity.

The moderating role of team inclusive climate

Team inclusive climate is defined as the overall perception of diverse team members of fair treatment, integration of differences, and inclusion in decision making in a team (Nishii, Reference Nishii2013). It is demonstrated that individuals from different backgrounds will outperform, if they are fairly treated, valued for who they are, and included in core decision making (Nishii, Reference Nishii2013). We are drawing on Nishii’s (Reference Nishii2013) assumptions of inclusive climate, which means in order to reduce problems associated with diversity, conflict, and turnover organizations need to create an inclusive environment. The inclusive environment promotes social and cultural inclusion (Azmat, Fujimoto, & Rentschler, Reference Azmat, Fujimoto and Rentschler2014). When cross-national team members perceive that they are fairly treated and valued for who they are, they will tend to consider themselves in-group, commanding respect, and power. These perceptions and intended outcomes will stimulate friendly environment develop psychological safety and promote frequent communication among cross-national team members, which will result in open discussions and knowledge sharing with each other (Ferdman, 2014). It has discussed that the surface-level diversity is negatively associated with team knowledge sharing (Williams & O’Reilly, Reference Williams and O’Reilly1998). To mitigate the social categorization effect and to enhance social cohesion, an inclusive environment is needed (Nishii, Reference Nishii2013). An inclusive climate facilitates social capital development, particularly team-bonding social capital, which is positively associated with team creativity (Han, Han, & Brass, Reference Han, Han and Brass2014). Hence, team inclusive climate could attenuate the negative effect of surface-level diversity on team knowledge sharing. We thus hypothesize

Hypothesis 5a: Team inclusive climate moderates the relationship between perceived surface-level diversity and team knowledge sharing in a way that the negative relationship will be mitigated when team inclusive climate is high.

The climate literature argues that an inclusive climate can catalyse the relationship between deep-level diversity and knowledge sharing (Nishii, Reference Nishii2013; Wang, Rode, Shi, Luo, & Chen, Reference Wang, Rode, Shi, Luo and Chen2013). Therefore, we can infer that in a highly inclusive climate cross-national team members engage with each other in more constructive ways. We believe that diverse team members contain and generate new thoughts and novel ideas, but they will share these ideas when feel included in the team. The underlying argument is that the inclusive climate promotes divergent thinking and encourages team members to share with teammates. Based on the arguments above, we propose

Hypothesis 5b: Team inclusive climate moderates the relationship between perceived deep-level diversity and team knowledge sharing in a way that the positive relationship will be strengthened when team inclusive climate is high.

Methodology

Sample and procedure

To test our hypotheses, we collected data from cross-national research teams in Chinese universities. The research teams consisted of international and Chinese graduate and postgraduate students working on research projects under their supervisors. We target cross-national research teams because team diversity, both surface and deep level, is more salient in cross-national teams. Tsui, Nifadkar, and Ou (Reference Tsui, Nifadkar and Ou2007) stressed that to achieve true findings research sample must represent characteristics of population and match with study objectives. In intranational teams diversity, especially deep-level diversity, may not be discern. Hence, cross-national teams precisely serve the objectives of this study. Teams were from different fields including life science, engineering, and business and administration. We distributed survey questionnaires to 239 participants that constitute 63 teams. In our study, the supervisor was considered as the team leader. Further, apart from the daily research activities of the team members in their labs, the supervisors hold team meetings for 2–3 h every week during which team members report their research progress and intensively discuss their research ideas with the supervisor and with other team members.

We requested team members to fill in the questionnaire during their break time in daily research activities. The questionnaire was contained in an envelope, and handed over to each team member. Each team member was asked to return the sealed questionnaire envelope to us. To evaluate the level of team creativity, teams’ supervisors, the team leaders were requested to evaluate teams’ creativity. An envelope containing the team creativity questionnaire, one page description about research, instructions about questionnaire, and prepaid envelope with return address were delivered to each supervisor through personal visit or by mails. We received valid responses from 223 team members (response rate=93.31%) and 60 team leaders (95.23%). The average size of each team was 3.72 (SD=0.89). Of the team members, 62.0% were male and the average age was 27.08 years (SD=3.68).

Measures

Perceived deep level and surface-level diversity

Scale used to measure the perceived deep level and surface-level diversity was adapted from Harrison et al. (Reference Harrison, Price, Gavin and Florey2002). The team members rated their responses on a 5-point Likert scale. The questionnaire asked to what extent team members are similar or different, 1=‘very similar,’ to 5=‘very different,’ on seven deep-level diversity variables (personal values, attitude about research work, personality traits, educational background, work commitment, objectives, and priorities at research work). A sample item was ‘The personal values of team members are “very similar” to “very different”.’ Using the same response format, four dimensions measured surface-level diversity (age, gender, race, and nationality). A sample item was ‘The age of team members is – (“very similar” to “very different”).’ We reported the Cronbach’s α for perceived surface-level diversity because the perception of team members on four surface-level diversity items was correlated. The Cronbach’s α for the perceived deep level and perceived surface-level diversity scales was 0.73 and 0.76, respectively. According to the recommended reliability criteria by previous researchers (Churchill & Peter, Reference Churchill and Peter1984), the reliability value, Cronbach’s α>0.70 is acceptable.

Knowledge sharing

We adapted a questionnaire from Chen and Lin (2013) to measure knowledge sharing among the team members. The team members rated their responses on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1=‘strongly disagree’ to 5=‘strongly agree’ on four knowledge sharing items (experience, expertise, ideas, and research material). A sample item is ‘In our research team, we share our experiences with each other’. All the items drawn from the mentioned source and text of the items were modified to fit our research context. For example, the original instrument measured ideas sharing as ‘We share our ideas about job with one another’. We slightly modified this item to ‘We share our ideas about research work with one another’. The Cronbach’s α for the team knowledge sharing scale was 0.85.

Inclusive climate

To measure inclusive climate, a shorter version of the scale used by Nishii (Reference Nishii2013) was adapted. The team members responded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1=‘strongly disagree’ to 5=‘strongly agree’ on 19 inclusive climate items of three dimensions, equitable practices (four items), integration of differences (eight items), and inclusion in decision making (seven items). Sample items are respectively ‘There is fair reward and recognition of activities in our team, Our team has a culture in which members appreciate the differences the members bring to team, and ‘In our team member’s input is actively obtained and pursued’. The Cronbach’s α for equitable practices was 0.90, integration differences was 0.92, and inclusion in decision making 0.92. All three dimensions were highly correlated; therefore, the overall Cronbach’s α for the inclusive climate scale was 0.95.

Team creativity

Team creativity was measured using scale developed by George and Zhou (Reference George and Zhou2001). To reduce the potential threat of common method variance (Podsakoff, Mackenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003), the supervisor of the research team rated team creativity at 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1=‘strongly disagree’ to 5=‘strongly agree’. The Cronbach’s α for the team creativity scale was 0.78. A sample item is ‘The team members suggest new ways to achieve goals and objectives’.

Control variables

Several variables were controlled for in order to reduce the concern that those variables may systematically influence the study results. Team leaders’ age, gender, education, and tenure were our primary control variables. Also, we controlled for team size because team size may influence the interaction and dynamics among team members (Kwak & Jackson, Reference Kwak and Jackson2015).

Preliminary analysis

Aggregation of variables at team level

Team creativity was measured at the group level by team supervisors. The remaining variables were measured at the individual level. The literature suggests that there should be agreement within team on responses to variable questions before aggregating any variable to the team level (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Price, Gavin and Florey2002). Therefore, to fulfil this assumption, we calculated the intermember agreement (r WG) and reliability interclass correlation (ICC) (1) and ICC (2) indices for each variable that was measured at the individual level.

Table 1 represents the results of the aggregation of the variables. For perceived surface-level diversity the mean r WG was 0.90, which indicates strong agreement within the teams (LeBreton & Senter, 2008). The r WG values were above the conventionally acceptable r WG value of 0.70 (James, Demaree, & Wolf, Reference Jehn, Northcraft and Neale1993). In addition, ICC (1), and ICC (2), were 0.35 and 0.70 (F(59, 163)=1.52, p<.05), respectively, for perceived surface-level diversity. The ICC (1), ICC (2), and the mean r WG values for perceived deep-level diversity were 0.38, 0.71 (F(59, 163)=1.75, p<.01), and 0.91, respectively. The ICC (1), ICC (2), and the mean r WG values for team knowledge sharing were 0.47, 0.78 (F(59, 163)=2.42, p<.001), and 0.86, respectively. Similarly, ICC (1), ICC (2), and the mean r WG values for inclusive climate were 0.38, 0.71 (F(59, 163)=1.68, p<.01), and 0.99, respectively. The results confirmed the variables aggregation; hence, we used them at team level.

Table 1 Aggregation of variables

Note. *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001.

Confirmatory factor analysis

Before testing the relationships among the constructs, we assessed their distinctiveness using confirmatory factor analysis. Against the baseline model of four factors (Model 1), we examined four alternative models (Models 2–5). Overall model fit was assessed by the comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (Marsh & Hau, Reference Marsh and Hau1996). The confirmatory factor analysis model is considered good fit when RMSEA is below 0.08 and IFI, TLI, and CFI values surpass 0.90 (Ngo, Foley, & Loi, Reference Ngo, Foley and Loi2009). As shown in Table 2, the nested models exhibited significantly worse fit than the baseline model, as seen from the significant χ2 difference tests and model fit indices. The baseline model of four factors fitted the data well (χ2=867.75, df=489, RMSEA=0.06, IFI=0.90, TLI=0.90, CFI=0.90). The standardized loadings of all indicators on their specified constructs were significant at the 0.01 level.

Table 2 Comparison of measurement models

Note. RMSEA=root mean square error of approximation; IFI=incremental fit index; TLI=Tucker–Lewis index; CFI=comparative fit index.

***p<.001.

Since common method variance (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003) is considered a potential threat to the validity of research findings, we minimized this issue in two ways. First, we collected data from two sources: research team members and their immediate supervisor (Richardson, Simmering, & Sturman, Reference Richardson, Simmering and Sturman2009). Second, we used the Harman (Reference Harman1960) single-factor test to examine the potential influence of common method variance. Results of our exploratory factor analysis using all variables in this study, yielded four factors with eigenvalues >1 that accounted for 55.75% of the total variance, with the first factor accounting for 35.76% of the variance. Therefore, a single factor did not emerge and one factor did not account for the bulk of the variance.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 3 presents the means, standard deviations and intercorrelations of all variables in the study. Specifically, as hypothesized, the zero-order correlation between perceived surface-level diversity and team creativity was −0.18 (p<.05). This shows a significant negative association between team surface-level diversity and team creativity. The correlation was 0.21 (p<.05) between perceived deep-level diversity and team creativity, showing a significant positive association between team deep-level diversity and creativity. The correlation was 0.55 (p<.001) between team knowledge sharing and team creativity, showing a significant positive association between team knowledge sharing and creativity.

Table 3 Descriptive statistics, zero-order correlations, and α reliability coefficients

Note. *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001.

Moreover, other results were consistent with and provided initial support for our hypotheses.

Hypothesis testing

We used multiple regressions to test the hypotheses. The results are shown in Table 4. In model 2, perceived surface-level diversity was negatively related to team creativity (β=−0.32, p<.05). The Hypothesis 1a was supported. Further, we found perceived deep-level diversity was positively related to team creativity (β=0.32, p<.05). Hence, Hypothesis 1b was supported.

Table 4 The regression results

Note. *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001.

Moreover, in model 2 of knowledge sharing, perceived surface-level diversity was negatively related to team knowledge sharing (β=−0.31, p<.05). This supports Hypothesis 2a. Perceived deep-level diversity was positively related to team knowledge sharing (β=0.52, p<.05), supporting Hypothesis 2b. In model 3 of team creativity, we found that team knowledge sharing was significantly related to team creativity (β=0.41, p<.05). It is supporting Hypothesis 3. We tested the mediating hypotheses, following the causal steps outlined by Baron and Kenny (Reference Baron and Kenny1986). When team knowledge sharing was entered in a regression equation with team surface level and deep-level diversity, the relationship with team creativity became nonsignificant (β=−0.19, NS), (β=0.10, NS), respectively. While team knowledge sharing remained positively related to team creativity (β=0.41 p<.05). It supports Hypotheses 4a and 4b.

Results for the moderator hypotheses are shown in Table 4. Following the requirements recommended by Edwards and Lambert (Reference Edwards and Lambert2007), we tested the moderation of inclusive climate on the relationship of perceived diversity and knowledge sharing. The interaction between perceived surface-level diversity and team inclusive climate was positively related to team knowledge sharing (β=0.36, p<.01). Hence, Hypothesis 5a is supported.

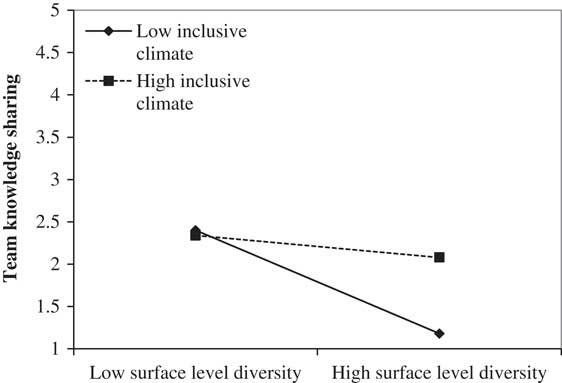

We plotted simple slopes following the procedure suggested by Aiken and West (Reference Aiken and West1991) at one standard deviation above and below the mean for team inclusive climate, shown in Figure 2. The plots show that perceived surface-level diversity is more strongly associated with team knowledge sharing for a higher level of team inclusive climate.

Figure 2 The moderating role of team inclusive climate in the relationship between perceived surface-level diversity and team knowledge sharing

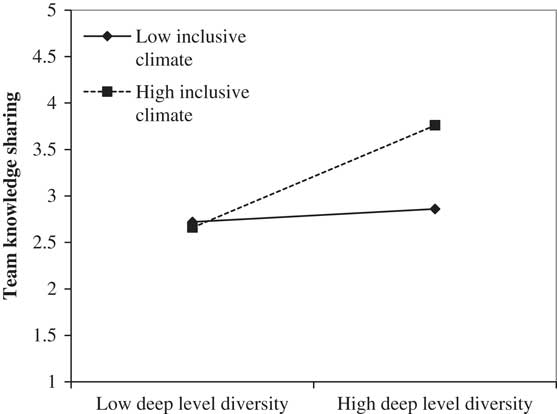

Similarly, following the same procedure for testing Hypothesis 5a, we run the moderation model to test Hypothesis 5b. As shown in Table 4, the interaction between perceived deep-level diversity and team inclusive climate is positively related to team knowledge sharing (β=0.24, p<.05). Thus, our Hypothesis 5b is supported. We again plotted the simple slopes for the relationship, shown in Figure 3. The plots show that perceived deep-level diversity is more strongly associated with team knowledge sharing for higher level of team inclusive climate.

Figure 3 The moderating role of team inclusive climate in the relationship between perceived deep-level diversity and team knowledge sharing

Robust test and analysis

Link between objective and perceived surface-level diversity

We used perceived diversity in cross-national teams to examine the relationship and mechanism between team diversity and creativity. To insure the relationship between team members’ perception of team diversity and objective team diversity on demographic characteristics (age, gender, race, and nationality), we conducted regression (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Price, Gavin and Florey2002). We used Blau’s (Reference Blau1977) index of heterogeneity (1−∑Pi 2) to calculate objective surface-level diversity (gender, race, and nationality) following the recommendations of Seong, Kristof-Brown, Park, Hong, and Shin (Reference Seong, Kristof-Brown, Park, Hong and Shin2015). In this formula, Pi is the proportion of a group in each of the i categories on the group. To reflect diversity in age of team members, we used within-group standard deviations. Peacocke’s (Reference Peacocke2001) asserted that the perceptual manifestation of concept significantly represents its objective characteristics. In the Table 5, regression coefficients are significant between objective surface-level diversity (age, racial, and nationality indices) and perceived surface-level diversity. Our robust test shows that the measurement of perceived surface-level diversity is as valid and effective as the objective surface-level diversity.

Table 5 Regression analyses of actual surface diversity on perceived surface diversity

Note. **p<.01, ***p<.001.

Discussion

We theoretically presented and empirically examined a model of perceived diversity and team creativity in which team knowledge sharing mediated the relationship. Moreover, we also found that inclusive climate moderates the relationship between perceive diversity and team knowledge sharing. Our findings make some significant contributions to team diversity and creativity research.

Contributions

Our investigation makes three contributions to the literature on team diversity and creativity. First, we established and tested a conceptual model that integrates team perceived diversity and team creativity in cross-national research teams. Our findings demonstrated that surface-level diversity and deep-level diversity have different effects which are consistent with the findings of Harrison et al. (Reference Harrison, Price, Gavin and Florey2002). Our findings indicated that surface-level diversity negatively influenced team knowledge sharing and team creativity. Several scholars have agreed that surface-level diversity stimulates social categorization (Chatman & Flynn, Reference Chatman and Flynn2001; Bell, Villado, Lukasik, Belau, & Briggs, Reference Bell, Villado, Lukasik, Belau and Briggs2011), which may restrain team knowledge sharing, creativity, and innovation. We also found that deep-level diversity was positively related to team knowledge sharing and creativity, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies (Shin et al., Reference Shin, Kim, Lee and Bian2012; Han, Han, & Brass, Reference Han, Han and Brass2014). The differentiated effect of perceived surface level and deep-level diversity contributes to diversity and creativity literature. The differentiated effect of diversity provides theoretical grounds that could help future research to examine diversity relationship with innovation, performance, conflict, and trust.

Second, we ascertained the relationship between team diversity and creativity through knowledge sharing. Based on information and decision-making perspective, knowledge sharing mediates the relationships of team perceived diversity (surface level and deep level) and creativity. Team diversity has been recognized as an important factor of team creativity (Shin et al., Reference Shin, Kim, Lee and Bian2012). Examining knowledge sharing as an intervening factor in cross-national team diversity (surface level and deep level) and creativity strengthens existing research findings (Cummings, Reference Cummings2004). It indicates that knowledge sharing in diverse team affects team creativity. This investigation thus explains a new perspective on understanding how team diversity influences team knowledge sharing, and consequently enhances team creativity. These findings contribute to team diversity–creativity relationship and information perspective.

Third, to our best knowledge, our study is the first in the diversity–creativity literature that empirically investigated a contextual factor, inclusive climate, in cross-national teams. It extends Nishii’s (Reference Nishii2013) line of thinking and responds to her call for investigating the moderating effects of inclusive climate in group processes and outcomes. We found that the inclusive climate attenuated the negative association between surface-level diversity and knowledge sharing. Thus, high level of inclusive climate diminishes the detrimental effect of demographic diversity. Inclusive climate facilitates deep-level diversity among cross-national team members that could result high team knowledge sharing and may lead to team creativity. Our findings contribute to the research of Shore, Randel, Chung, Dean, Holcombe Ehrhart, and Singh (Reference Shore, Randel, Chung, Dean, Holcombe Ehrhart and Singh2010) and Nishii (Reference Nishii2013) to investigate the conditions under which team diversity positively relate to creativity. This study also contributes to inclusion literature that inclusive climate is a significant contextual factor that leverages potential of diversity in cross-national teams.

Taken all together, team inclusive climate explained the condition that overcomes the negative effect of perceived surface-level diversity and boosts the positive effect deep-level diversity on knowledge sharing. Consistent with the trailblazer (Nishii, Reference Nishii2013), we found that inclusive climate reasonably explains the context when team perceived diversity positively influences team knowledge sharing, which may lead to team creativity.

Implications

Our investigation sheds additional light on diversity–creativity relationship. Consistent with Harrison et al. (Reference Harrison, Price, Gavin and Florey2002), surface-level diversity and deep-level diversity have effect differently. It is very important to know how different types of team diversities influence team creativity (Lauring & Selmer, Reference Lauring and Selmer2012). Team knowledge sharing found intervening mechanism that explained the relationship between team diversity and team creativity. The major theoretical implication of this investigation is the contextual factor, inclusive climate, under which positive influence of team diversity nurtures. In line with Nishii’s (Reference Nishii2013) assumptions, our results provided evidence that inclusive climate leverage positive, and retain negative effects of diversity.

We have demonstrated that team creativity is very important for organization. Our findings implied that team surface level and deep-level diversity could affect team outcomes differently. Thus, managers should consider different outcomes of different diversity type. Hence, they should facilitate the conditions for positive outcome of diversity and compose the team with right mix of diversity (Cheng, Chua, Morris, & Lee, Reference Cheng, Chua, Morris and Lee2012). We found that knowledge sharing was the intervening between team diversity and creativity. It showed how team diversity affects creativity. Thus managers should pay more attention to the mechanism of diversity–creativity relationship. They should seek to promote knowledge sharing among the diverse team members, such as encourage communication, frequent meetings, and collective work, to leverage team creativity. As our findings suggested that inclusive climate significantly moderates team diversity and knowledge sharing relationship. The managers should cultivate an inclusive climate in cross-national teams by appreciating the members’ differences, providing them equal opportunities, and involving in decision making.

Limitations and future directions

There are some limitations of this study. First, the external validity of the research findings may be a concern because of the use of a cross-national student team sample. We precisely took special care to sample cross-national research teams which were working on combined projects. The research teams would exist whether or not we conducted this research. Researchers (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Price, Gavin and Florey2002; Han, Han, & Brass, Reference Han, Han and Brass2014) have used similar typologies and stressed that student samples can express the characteristics of the work force. Future research should use research teams from business organizations, research institutes, and R&D centers to explore the cross-national team diversity and creativity. Second, subjective measures for team creativity were used because teams included in the sample were from different fields. However, we used widely accepted proxy measures for team creativity (George & Zhou, Reference George and Zhou2001), rating by a team supervisor. Future research could use objective measures of creativity (patents, applied patents, copy rights) from same field. Third, we found knowledge sharing to be a mediating mechanism between cross-national team diversity and creativity. Perry-Smith and Shalley (Reference Perry-Smith and Shalley2014) and Zhou, Shin, Brass, Choi, and Zhang (Reference Zhou, Shin, Brass, Choi and Zhang2009) demonstrated that heterogeneous team members’ network structure potentially influence team outcomes. We predicted inclusive climate moderated the relationship between cross-national team diversity and knowledge sharing. Future research should analyze moderation–mediation or mediation–moderation models. Future studies should use other variables such as team integration, conflict, person-group fit, trust, better communication, and organization climate as intervening and contextual variables to better understand diversity–creativity relationship. We studied cross-sectional phenomena between diversity and creativity in cross-national teams. Future researcher should use a longitudinal design to investigate the relationship between team diversity and creativity, following Harrison et al. (Reference Harrison, Price, Gavin and Florey2002). Over time, examination of cross-national team diversity and creativity phenomena could provide new insights of how creativity evolves in diverse teams.

Conclusion

Our results present compelling evidence of the relationship between perceived team diversity and creativity. This study demonstrates meaningful different effect of perceived surface level and deep-level diversity on team knowledge sharing and creativity. We found negative effect of perceived surface-level diversity and positive effect of perceived deep-level diversity on team knowledge sharing and creativity. Team knowledge sharing is identified as significant intervening mechanism that prudently explain the relationship between perceived team diversity (surface level and deep level) and team creativity. Most importantly, the inclusive climate is found prominent condition that dilutes the negative effect of perceived surface-level diversity and elevates the positive effect of perceived deep-level diversity on team knowledge sharing. Overall, our study suggests that different effect of team diversity (surface level and deep level) offers more realistic findings and explaining mechanism and boundary condition in diversity–creativity relationship portraits comprehensive approach.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the National Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 71072055; 71132003; 71132006; 71421002; 71602140) for the research and publication of this article. The opinions and arguments expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the National Science Foundation of China.