Even now widely considered the world's greatest tenor, Enrico Caruso was the most famous Italian alive in the early twentieth century.Footnote 1 Such notoriety is not, though, the only reason he receives attention: he was also the singer, or so the story goes, whose voice made listeners believe in, and pay for, music on record. This aspect of his biography flourished in the years after his death in 1921. In an early issue of The Gramophone – the first British publication aimed at consumers of recorded music – editor Compton Mackenzie wrote:

If you are anxious to test the measure of Caruso's vitality, consider what he has meant to the gramophone. He made it what it is. For years in the minds of nearly everybody there were records, and there were Caruso records. He impressed his personality through the medium of his recorded voice on kings and peasants. Everybody might not possess a Caruso record, but everybody wanted to possess one, and a universal appeal such as his voice made cannot be sneered away by anybody. People did not really begin to buy gramophones until the appearance of the Caruso records gave them an earnest of the gramophone's potentialities.Footnote 2

By 1952 the idea that Caruso unleashed the power that created a musical medium was commonplace, so much so that the journal Life could refresh its readers’ memory in the following terms: ‘So great was Caruso's prestige, even then, that the phonograph automatically became socially accepted.’Footnote 3 Over the decades since, this idea of Caruso's historical influence over listeners has been revived time and time again.Footnote 4

The notion is alive and well in the twenty-first century, as scholars across the humanities have started to re-examine sound reproduction technologies and the question of what made listeners pay attention to them.Footnote 5 In one of the most thorough accounts of Caruso's aural attraction, historian David Suisman notes that his personality was in active synergy with an emerging star system that lured listeners to the gramophone industry.Footnote 6 Furthermore, Suisman argues that the singer became an early mass media celebrity because his recordings were blessed with a highly distinctive, ‘manly’ voice: listeners could recognise him by sound alone and then associate that sound with a celebrity persona, perhaps even awakening a desire to be similarly recognised (Suisman notes an early twentieth-century cult of personality in North America that gave rise to countless manuals on how to become one's own ‘personal brand’ through dress, comportment and voice).Footnote 7 By such means, Caruso is said to have instigated a wave of consumption in gramophones and discs, particularly among the middle classes, and set in motion a series of events with far-reaching consequences for the development of the music industry. He provided, according to this narrative, an early demonstration of the fact that a sung performance could be mechanically reproduced while retaining the acoustic signature of the performer's vocal emissions.

Suisman gives new depth to an old example by exploring Caruso's role in recruiting gramophone listeners by means of the broader dynamics of celebrity at play within the North American mediascape. However, his book leaves Caruso's well-known identity as an Italian in the United States largely unexplored.Footnote 8 In a more recent treatment of the ‘first Neapolitan star’, Simona Frasca explains how the Italian diaspora of which he was part shaped his celebrity, in part through recordings.Footnote 9 As well as many Italian and some French operatic numbers, and a few popular songs in English, Caruso recorded several Neapolitan songs (sung in his Neapolitan mother tongue), beginning this strand of his repertory in the early 1910s, the peak years of mainly southern Italian working-class emigrants arriving in the United States.Footnote 10 Frasca suggests that these recordings circulated widely among New York's colonia – the term used by elite Italians to refer to Little Italy – providing an important vector to Caruso's surging celebrity. This tranche of consumers was drawn to Caruso by contemporary politics: in the context of settler-colonial racism, which framed Neapolitans as ‘darker’ than white Americans, Caruso provided a positive image of the southern emigrant by calling on Italy's prestigious operatic heritage.Footnote 11 To put this another way, his records enabled an assimilationist dream of acceptance within US society without any loss of Neapolitan identity.

Suisman and Frasca offer important reappraisals of Caruso's relationship with the gramophone: not only as the product of celebrity fascination among white middle-class society but also catering to the desire for ‘whitening’ among the southern Italian diaspora in the United States.Footnote 12 Both elements of historical explanation are called forth by the present-day scholarly agendas and take on new significance in an age of sound studies. Here the Caruso story insistently raises a problem of historical narration: how to explain the arrival of a moment when ‘music’ placed on ‘record’ engaged listeners en masse for the first time. His gramophone career has come to stand for the early growth of a consumer reflex, one that ultimately led – by way of tape, vinyl and server farms – to the micro-monetisation of music in the present day.

In this article, I revisit the Caruso-plus-disc narrative, in particular to track its evolution in the history of listening. I will argue that the singer could be said to make a ‘new musical consumer’, along with a new medium for sound, only after his death. As my first, long quotation from Compton Mackenzie might begin to suggest, the origin story about listeners-beginning-to-attend took hold a few years after the tenor's disappearance from the world. These new stories attributed grandiose powers to Caruso's voice to make musical media, yet (paradoxically) denied the singer any agency in his own reproduction: he became the gramophone industry's unwitting rainmaker, whose voice just so happened to resonate with technologies and listeners of the past.Footnote 13 By contrast, in revisiting Caruso's life and death through the lens of discs, I will try to reconstruct his agency in his reproduction as a political negotiation. More broadly, I want to show how Caruso's death has lent force to those who, following Mackenzie's lead, make claims about the singer's influence over gramophone listeners of yesteryear, even as his many entanglements with the Italian diaspora are routinely forgotten. In other words, my larger aim will be to track the aural habits of mind that Caruso's discs have helped to create over time, while exploring a more multi-sensory, more distributed imagination of voice/listening c.1900.

Voice of gold and bronze

Caruso was born in Naples in 1873 to a working-class family. His father was a metal mechanic, a trade he encouraged his son to follow, apprenticing him at an early age to a factory that made (probably) bronze water fountains for the city. His mother, a cleaner, insisted Caruso attend school in the evenings, where he sang in a cathedral choir and studied technical drawing.Footnote 14 Caruso's operatic breakthrough came in his early twenties at Naples's relatively small Teatro Nuovo, with a minor role in Mario Morelli's L'amico Francesco (1894).Footnote 15 The opera was bankrolled by the little-known composer and performed perhaps only twice.Footnote 16 Nevertheless, the event provided a launchpad: a number of engagements followed, both in Italy and abroad. Before the nineteenth century was over, Caruso had appeared in Rome, Cairo, St Petersburg, Moscow and Buenos Aires.Footnote 17

Near the end of 1900, Caruso sang for the first time at Milan's Teatro alla Scala, opening the new season in Italy's most prestigious opera house. It was an important milestone, drawing further international attention. In January 1902, after observing Caruso perform in Milan, a representative from London's Gramophone Company invited him to record ten numbers – an invitation that Caruso, perhaps reluctantly, accepted.Footnote 18 The recording session took place a few hundred metres from La Scala: at the Hotel Milan where, famously, Giuseppe Verdi had died the previous year. Caruso recorded some well-known tunes – notably ‘Questa o quella’ and ‘Celeste Aida’, staples by the recently deceased Verdi, perhaps intended as an homage; but his selection came largely from operas composed in recent years, including the aria ‘Studenti, udite!’ from Alberto Franchetti's Germania, which had premiered at La Scala only the previous month. In other words, his earliest repertoire envisioned the gramophone as a medium both for archiving the canon and for broadcasting and advertising more recent operas.Footnote 19

What induced Caruso to record, where other opera singers had refused the Gramophone Company's offers? The issue has been deeply pondered, giving rise to a potent mythology of its own.Footnote 20 As well as the cash, it is likely that the promise of fame provided an important incentive. But perhaps his familiarity with metals played a supporting role. Caruso's early experiences in constructing water fountains meant that, unlike many contemporary performers, he was primed to understand the processes by which wax moulds were cast. In the Hotel Milan, Caruso's voice was engraved in a wax master that would later, in a Gramophone Company factory, be coated in copper and then nickel – progressively harder-wearing metals – through electroplating. The goal was to convert vocal etchings into tough ‘stampers’, which would resist pressure when pressed into a shellac mixture heated by steam.

It was in part due to his Milanese discs that Caruso came to New York's Metropolitan Opera House for the first time in 1903. The Met's director, Heinrich Conried, heard of Caruso's growing reputation in New York on a talent-scouting trip to Paris that summer, but did not listen to him sing ‘live’: he invited Caruso to join his company in New York on the strength of elite word of mouth, along with the testimony of those recordings the tenor had made the previous year.Footnote 21 For Conried, this endorsement provided by recordings would have been something of a novelty in the multi-stage rigmarole of selecting and hiring opera singers, offering him a further guarantee of Caruso's good voice. What is more, discs called attention to the singer's increasing circulation on an international opera circuit; they marked an empty space in which he could be imagined, and perhaps desired in a new way.

But many more agents were involved in the reproduction of Caruso's increasingly famous voice. For example, ahead of his arrival in New York, his contract was negotiated by Pasquale Simonelli, a banker.Footnote 22 Simonelli was himself a relatively new arrival in North America, having migrated from Naples in 1897 to try his luck among New York's Italian elite – first as a language tutor and librarian, then as a clerk at the Italian Savings Bank.Footnote 23 He was well suited to Caruso's purpose: in addition to his Neapolitan credentials, he was a member of the Republican Party and had acquired other useful connections in the United States. Despite initial misgivings about the contract Simonelli created, Caruso was eventually deeply grateful to the banker – so much so that he gave Simonelli a gold medallion, engraved with the words ‘per ricordo’ (‘to remember me by’).Footnote 24

These personalised gold coins involve overlapping themes in Caruso's New York sojourn. He already knew about metal work, of course; and the minting of medallions was customary for well-to-do personages across the long nineteenth century, functioning as both presents and souvenirs.Footnote 25 But Caruso did something different: he produced very small, inexpensive imprints of himself that could be more freely distributed. He even imported the practice into the recording studio, as his first biographer, Pierre Van Rensselaer Key, recorded shortly after Caruso's death: ‘Often he came to the recording laboratory with little souvenirs for members of staff and the orchestra; and once he brought each of them a gold medallion with a bas-relief of his head on one side.’Footnote 26 These mini-souvenirs complemented the making of discs – the one a mould of his profile, the other his voice – bringing two related modes of reproduction into contact. Taken together, they can mark what we might call Caruso's agency in his own reproduction, representing the value he attached to personal replication. Doled out at the recording studio, these coins symbolically repaid a debt to musicians and laboratory technicians in helping reproduce his voice; at the same time, they actively enlisted their recipients’ services (and good opinions) as workers, further enhancing his celebrity personality.

Circulation

The Simonelli medallion and its replicas present Caruso at the fulcrum of interlocking circulations: as a singer ascending through a cosmopolitan opera circuit, but also as a famous Neapolitan in transit to and from an elite Italian community of bankers, doctors and operagoers in New York. These areas of circulation were not wholly separate. Many people, including musicians and opera singers, belonged to both, and Caruso benefitted from commanding audiences already familiar with (or interested in) opera while also calling on ethnic pride from the Italian diaspora.Footnote 27 Yet his celebrity was the product not only of the combination between these two sets of listeners but also of productive tensions between them: tensions that supercharged Caruso's circulation through a clash of political interests.

Consider the most well-known anecdote about Caruso: the so-called Monkey House Incident of 1906, in which he was accused of sexually harassing a woman who then vanished before the trial.Footnote 28 On 16 November he was arrested in (or near) the primate house of New York's Central Park Zoo on the charge of ‘annoying women’, specifically a young woman called Hannah Graham.Footnote 29 The day after the arrest, the New York Police Department held a press conference in which the arresting officer revealed some intimate particulars:

[Caruso] wore a single-breasted overcoat, with a cane stuck upright in the pocket. His hands were in his pockets, and I never could make out … just how he used them to such annoyance, for he never took them out. After arresting him on Friday evening I examined the coat, and found that there was a slit in one of the pockets. Through this he could reach out a hand through the buttoned space.Footnote 30

Two days later, another press conference was held at the Metropolitan Opera. Caruso was present but Conried spoke on his behalf, reading out a prepared statement that declared the tenor's innocence. As Caruso looked on, Conried re-enacted the scene, later described in the Washington Post:

One of the reporters played ‘Mrs. Graham’. Mr. Conried put both his hands in his pockets, looked at an imaginary monkey up near the wainscoting, and brushed gently against the reporter, instantly bowed and moved over toward the corner of the room.Footnote 31

Except for a few remarks in French – Caruso could neither speak nor understand English, a fact that later became important to his defence – the singer remained silent; others spoke about him and on his behalf.

When Caruso arrived at Yorkville Magistrates Court a few days later, the room was packed with around six hundred people, including several prominent operagoers; there were a thousand more on the staircase outside.Footnote 32 According to the New York Times, those present could be divided into ‘Italians’, who shouted Viva Caruso!, and ‘Americans’, who hissed.Footnote 33 The legal proceedings opened with a shock for the defence: the public prosecutor – and former police chief – James A. Mathot produced fresh allegations. Caruso had harassed not only Graham in the primate house but several others elsewhere: two ‘respectable’ women, a ‘colored lady’ and two girls.Footnote 34 Graham did not appear at any point during the trial, and part of Caruso's defence was that no such person existed; the police, it claimed, were unwilling to produce the key witness for fear of exposing a long-standing scam in which they were actively implicated.Footnote 35 However, the police did produce another female victim who alleged that Caruso sexually harassed her, and so attempted to establish a history of abuse. This new witness entered the court covered in a heavy white veil and never spoke, nor was her name ever revealed. As she uncovered her face, Mathot asked Caruso (through an interpreter): ‘Do you recognize this woman?’ Caruso said he did not. Mathot went on to ask whether Caruso had once leaned against this woman's back in the Met's standing section during the second act of Wagner's Parsifal. Caruso again answered ‘no’; the defence objected that Mathot was firing off questions ‘simply to get into the newspapers’. The magistrate refused permission for Mathot to call a second, again anonymous witness, whom, it was suggested, Caruso had abused at a horse show.

Mathot's strategy in calling female witnesses was to distract from Caruso's initial accuser's non-appearance, while presenting a larger context for the singer's supposed actions in the monkey house: the very real problem of sexual harassment in New York, which Mathot smoothly combined with nativist fear of male immigrants.Footnote 36 Eliding the enormous differences between elite and working-class Italians in New York (the latter being the primary targets of nativist fear), Mathot singled out the wealthy Italians who had come to court to support Caruso during his closing address:

I am not here as a representative of the Police Department or as a defender of [the arresting officer], but I am here in the name of decency, and I ask, in the names of our wives and of our children and of every honest man in the community, that you give a decision that will impress on these misfit wretches, these perverts, the fact that they cannot insult honest women on our highways as they strive to do.Footnote 37

Mathot's insult provoked an outcry from the gallery. Nonetheless, the following day, the magistrate returned to declare Caruso guilty, sentencing him to a fine of a $10 (although sparing him severer punishments of imprisonment or hard labour).

In recalling in some detail this notorious episode from Caruso's early years in New York, I want to underline the manner in which he was represented: the heightened theatricality that extended from the trial to its extensive newspaper coverage, which revelled in playing off Caruso's distinct personas as an opera singer, on the one hand, and as Italian in New York, on the other, against one another. The fact that Caruso did not speak English well and often spoke through interpreters was somehow crucial: it prompted Conried's re-enactment of the crime; journalists scanned his face for signs he comprehended what was being said about him, remarking on his apparent boredom in constantly twirling his moustache.Footnote 38 The tenor's muteness called attention to his physical presence, creating an amusing distinction between his putatively transgressive body and his famous voice. His silence mirrored that of the veiled woman presented by the prosecution: she, too, became a mute body in the courtroom, the object of endless speculation and chatter.

Caruso did, however, have an opportunity to respond a few months later, when he began working as a caricaturist for the Italian-language satirical newspaper La Follia di New York (The Madness of New York). In January 1907, the newspaper's editor invited Caruso to cover the annual banquet of the New York Camera del Commercio. He dutifully drew prominent men in attendance – diplomats, ambassadors, aristocrats and newspaper editors – and his efforts were published shortly afterwards on the front page: pairs of tuxedoed figures occupied the corners, while the caricaturist himself featured at the centre (his hands inside his much-discussed pockets). According to the caption, Caruso stared menacingly at a certain ‘Cavaliere “M”! A mystery!’Footnote 39 In veiled language, although easy to decipher for an Italian readership apprised of recent events, Caruso represented himself as sending a mock-vengeful glance in Mathot's direction.

Following this debut as a caricaturist, Caruso supplied drawings for La Follia on a weekly basis for much of the rest of his life. Mainly featuring lawyers, businessmen and musicians in New York, although occasionally also famous women, these sketches were for the most part mild in their satire, largely serving to flatter prominent people in the colonia and its orbit. The tenor's secondary vocation became well known beyond the North American Italian press, and was soon monumentalised in a bilingual, luxury edition spearheaded by La Follia's editorial team. The books generated advance demand, as revealed by the following ‘Letter to the Editor’, which appeared on the front page of La Follia in 1907:

Dear Sir, I have received the three copies of ‘Follia’ I requested, in which I admired the splendid caricatures by Caruso. Caruso is a wonderful man. A few days ago, I saw an advert for the ‘Book of Caruso’ but the price ($50) put me off. If in said book there were some original sketches drawn by his own hand, then I can see why it would have such great value.

I do not know Enrico Caruso, nor had I ever heard him sing (an unpardonable error) before the last season; but, having to judge from the public that goes to the Metropolitan Opera House, I must infer that he has many admirers and is very popular, more popular than one would think. and this despite all the gossip spread about him last winter – which, needless to say, i never believed.

With pleasure, I send you the two dollars for a year's subscription to ‘Follia’. there is no price not worth paying for a newspaper that has the honour to publish original sketches by the great tenor enrico caruso.Footnote 40

This letter was signed by Helen Weston, introduced by the paper as a ‘signorina americana’ who has ‘perfect knowledge of our language’. The editor highlighted in capital letters what he took to be the take-home messages: the great expense of the volume could only be justified by the images’ authenticity (the demand for original images rather than reproductions); and this operagoer – an American woman, no less – never believed the rumours stemming from the monkey house (even as those rumours had greatly increased his public profile).Footnote 41

Weston's letter furnishes further hints as to how Caruso's voice related to his caricatures. She presented herself as someone who had not heard Caruso sing until recently, but even so felt obliged to judge his performance from the reactions of others, to ‘infer’ that he was widely admired. In other words, his voice remained elusive even when she heard it – in performance and perhaps on disc – and could benefit from the support of a more tangible, more easily legible, supplement. His caricatures created a record of operatic performance, providing a means through which readers could approach his voice by way of his sketching hands.

Masks and doubles

The publicity brought about by the monkey house incident meant Caruso's case echoed through the cosmopolitan West. A sketch showing him confronted by the veiled woman in court provided the front cover for Paris's Monde illustré; in-depth news coverage reached the notice of James Joyce, then living in Trieste, who later recycled the material for Leopold Bloom's trial in Ulysses (1922).Footnote 42 In New York, Caruso was no longer just a famous opera singer. He was, for example, the target of a scene in the 1907 Ziegfeld Follies in which he was ‘tried on stage (by a jury of twelve beauties) for his then famous antics’, in a skit that featured famous Broadway actor Anna Held (Florenz Ziegfeld's wife) as ‘Mrs. Innocence’.Footnote 43 The skit's song, ‘My Cousin Caruso’, was performed by Charles A. Bigelow, a well-known comic actor; composed for the occasion by Gus Edwards and Edward Madden, it gives voice, in heavily accented English, to a Neapolitan immigrant to New York who alleges family ties with the Metropolitan Opera's greatest star. Its melody liberally quotes from the famous phrase from Pagliacci, ‘Ridi, pagliaccio, con il cuore infranto’ (‘Laugh, clown, though your heart is broken’), set to new words (‘His voice so sad-a, Drive de ladies all mad-a’) to enact the immigrant's attempt to sing like his famous cousin.Footnote 44

Such attention brought about a shift in the way Caruso was talked about, refreshing the opposition between his operatic voice and immigrant body already established by the monkey house fiasco and the subsequent trail – a split staged in the song through a double exposure of the tenor and his dubious relative. Caruso was not only aware of such doubling, but actively encouraged it. Musicologist Larry Hamberlin quotes extensively from an account of Caruso performing at a benefit concert, where Gus Edwards sang ‘My Cousin Caruso’: ‘The audience howled at the catch lines, and Caruso screamed louder than anyone else at Gus's efforts to satirize him.’Footnote 45 Such competitive laughter can be read in many ways, not least signalling discomfort mixed in with delight at the masquerade. The evocation of Caruso's cousin as a Neapolitan type recalls blackface minstrelsy, a theatrical and political institution very much alive in the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century.Footnote 46 Laughter was more or less compulsory in such contexts as a way of communicating racist pleasure among audience members; as Eric Lott has described, ‘the scarifying vision of human regression implicit, for whites, in “blackness” was somewhat uneasily converted through laughter and humor into a beloved and reassuring fetish’.Footnote 47

Within this theatrical context, as both the object and the subject of laughter, Caruso's racial identity was darkened and whitened all at once: he became ‘whiter’ in his identity as an opera star and ‘blacker’ through his biological relation, reinforcing the split between body and voice.Footnote 48 In another, more enduring act of auto-exoticisation, Caruso sculpted a miniature bust of himself in the act of laughing that constitutes a multi-layered performance of race. In the shape of a laughing Buddha, perhaps intended to function as a decorative bookend, the statuette invokes orientalism and chinoiserie (and kitsch); yet, with eyes closed and mouth open wide, and cast in blackened bronze, this object may also cue blackface minstrelsy (Figure 1). At the same time, Caruso-as-Buddha makes sidelong reference to the tenor's signature aria from Pagliacci, in which ambiguous laughter featured so prominently. No doubt this mini-bust was meant to be funny: it invites laughter from its beholder, even as it catches Caruso's own laughing mid-convulsion.Footnote 49 Eight impressions of the mould were struck in 1909 at the Roman Bronze Works, owned by Genoese chemical engineer Riccardo Bertelli – the most important Italian foundry operating in early twentieth-century New York. In terms of both the means and the content of representation, these statuettes record a celebrity marked by recent events in the city: he is a laughing man encased in a metal body.

Figure 1. ‘Caricature self-portrait bust by Enrico Caruso’ (1909), sculpture in blackened bronze. Museum number S. 104–2015. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

A decade later, Caruso created a more public monument to his Neapolitan relation. Apparently inspired by Edwards and Madden's song, he featured in the silent film My Cousin (1918) in which the cousin is redeemed as a real, long-lost cousin, and a veritable dopplegänger. Produced by the prestigious Hollywood company Famous Lasky Players, the script was supplied by Margaret Turnbull, a Scottish writer on the staff: it was an all-Caruso extravaganza in which he appeared in both title roles – as the world-famous singer, Cesare Caroli, and as Tommaso Longo, his cousin who (as an intertitle informs us) ‘carves out a meagre living sculpting models for the Italian plastering foundries’ in New York. As such, the film offers a belated response to an earlier strand of satire, reshaped into a tale of the singer's two bodies in which we see Caruso mime ‘Vesti la giubba’ from Pagliacci (including the notorious hysterical laugh) on stage before a packed audience as his as-yet undiscovered cousin looks down from the gods.

In the 1910s, many films revolved around human doubles, exploiting the medium to incorporate elaborate trick shots.Footnote 50 My Cousin turns on two such moments. The first comes shortly after Cesare's performance at the Met and takes place in an Italian restaurant: Tommaso orders a round of drinks for everyone present and proposes a toast to the famous tenor. Cesare watches the scene with satisfaction from a private booth and then makes to leave: in an extend shot, he walks from the deep background towards the exit, passing Tommaso on the way. As they approach each other, Tommaso enjoins the stranger to raise a glass to Italy's beloved tenor, an offer that Cesare declines. Once the singer has left, the restaurant's owner reveals to all that they have been in the presence of the great Cesare Caroli, and Tommaso is crestfallen not to have recognised him. A second shot showing two Carusos – this time perhaps through a double rather than a trick shot – occurs near very the end of the film, enacting the long-delayed reunion between cousins.

My Cousin was a disaster at the US box office and did not circulate widely. Film historian Giuliana Muscio argues that its failure was due to Caruso's unwillingness to participate in US stereotypes about violent Italians, along with the story's prevailing focus on Tommaso rather than Cesare, foregrounding the experience of Italian immigrants at the expense of screen time for the famous singer.Footnote 51 But there may be other reasons why Caruso's New York cosmology of migrant doubles failed to appeal. It is significant, for example, that Tommaso makes casts for the Italian foundries, recalling both Caruso's father's trade and the singer's own mould-making. The first scene reveals Tommaso at work in his studio surrounded by classical figurines in plaster waiting to be cast in metal, the largest of which is covered with a white sheet, later to be revealed as the cast of a life-size bust of Cesare Caroli. During the course of the narrative, this bust becomes an important character in its own right – a third Caruso. Not merely a reproduction, it becomes an agent of recognition when it prompts Cesare to remember the chance meeting with his cousin at the restaurant, in a memory visualised through elaborate crosscutting (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A still image from My Cousin (1918): this cross-fade shows Cesare Caroli (Caruso, seated) remembering meeting his cousin Tommaso (Caruso, standing) in a restaurant, but failing to recognise him. Tommaso's bust of Caroli also appears in this shot. The film is in the public domain; see https://commons.wikimedia.org/ (accessed 27 February 2020).

When the two cousins finally meet in the closing scene, Cesare is accompanied by the cast of himself. As a street party unfolds in Little Italy, he enters Tommaso's studio and (at long last) acknowledges his relation and offers him a lucrative commission to recreate the bust in marble. The pendulum swing between singer and cousin, original and copy, that extends throughout the film thus ends in the latter's favour, inviting empathy with the plight of the penniless artist and perhaps, by extension, Italian immigrants in general. This may be the principal reason why My Cousin was a flop, as Muscio suggests: that it appeals to non-existent empathy from mainstream (white, middle-class) moviegoers of the time. But it is also possible that in the late 1910s, at the height of Caruso's fame and prestige, the story of Caruso-as-immigrant could no longer command the resonance it once did – that North Americans found it harder to suspend disbelief and draw pleasure from the juxtaposition of two Carusos.

Despite its lack of circulation, My Cousin reflects deeply on the politics of Caruso's reproduction and its Manichaean shape. It calls attention to the collective expenditure of attention involved in the replication of any famous personality, along with the more particular racial dynamics of repulsion and attraction engaged through Caruso's stardom around the Atlantic seaboard. An unapproachable distance separates the estranged relatives for most of the film, a distance that is ultimately overcome by way of a bust, which makes the famous singer go in search of his audience member. My Cousin enacts a magical reversal of celebrity dynamics by which an audience member comes to ‘know’ an opera star, staging the fantasy of a celebrity in pursuit of his fan. In this way, the film pays muted homage to the larger patterns of economic migration on which Caruso's celebrity relied. And beyond this vast human circulation, it also stages a tribute to the materials through which ‘he’ travelled. The film's true hero is neither the singer, nor the cousin, but the bust, which stands in for the labour expended in the reproduction of personality through drawings, coins, statuettes – and discs.

Disc life

To sum up one strand of the argument so far: placed alongside other visual media and plastic forms, Caruso's early circulation on gramophone discs may appear differently. In the recording studio, the singer offered small gold tokens bearing his profile, as if in an exchange between craftsmen, a face for a voice. Alternatively, when placed next to his caricatures – similarly intended for wider circulation – Caruso's discs might be understood as pictures: sketches of performance that overcame the passage across the footlights, at once acknowledging and inscribing the distance (noted in Weston's letter) between performer and audience member. For their part, busts and statuettes find analogies in both the industrial processes by which discs were made and the human shapes they enfolded: the making of Caruso moulds and casts in marble, metal and shellac mixtures; their desirable likenesses to his body, mouth and voice. Told in this context, the story of Caruso's discs is no longer centrally about drawing listeners to a new medium, but rather about yet another mode of a historical celebrity, yet another means for transmitting a virtual person.

Caruso's most well-known disc can be productively reviewed and reheard in this vein. ‘Vesti la giubba’ was recorded (for the second time) in 1904, shortly after his arrival in the United States. More than any other record, this disc has been marked out for its power to attract listeners to the gramophone: it was, or so we frequently read, the first ever to sell a million copies (to ‘go platinum’). However, popular sources that repeat this claim – such as the Guinness Book of World Records – avoid mentioning when the millionth copy was sold.Footnote 52 Early accounts from the trade press, by contrast, present a looser affinity between Caruso and early disc listeners – such as when, in 1907, a Philadelphia-based gramophone salesman reported that his customers were requesting demonstrations from the tenor, although, he pointed out, not any song or disc in particular.Footnote 53 Recorded among the pages of Talking Machine World, this local snapshot warns against reading ‘Vesti la giubba’ as an instantly acclaimed hit. More likely, it accrued its devotees over time, as an eminently collectable operatic souvenir. That notwithstanding, it became – as the ‘My Cousin’ parody underscored – an aria and a role deeply linked with Caruso: a song about a clown applying theatrical make-up, which could construct the disc itself as a celebrity mask.

Such analogies between discs and other moulds may, at first blush, seem fanciful, but they allow us to go beyond the imperatives of historical advertisements, which stridently told listeners what to think and how to listen. This kind of commercial material now comprises a dominant source of evidence within sound studies, being thought to illustrate graphically both a mode of consumption under (white, male) capitalism and a particular way of listening. With ‘everyday’ accounts of listening widely scattered and harder to retrieve, historical adverts seem to present us with the dominant cultural logics of the marketplace. Yet, famous adverts that assert equivalence between man, voice and disc – ‘Both are Caruso’, ‘Caruso's Glorious Voice Kept for Posterity by the Phonograph’, and so on – prove to be ambiguous kinds of utterance. On the one hand, their phatic assertions point to their opposites (as Jonathan Sterne has noted, ‘Both are Caruso’ immediately engages the reasonable suspicion that both are not, in fact, Caruso).Footnote 54 On the other, the very chattiness of adverts can distract from quieter material contiguities.

The plastic analogies recovered in this article, by contrast, point to a historical epistemology for Caruso's recordings in which sounds were not only the content of discs but also an elaborate frame (alongside adverts, record catalogues and disc labels) for the personal properties contained within. Urged on by collectors with diverse motivations, the indexing of the performer's body provided the basic impulse for disc-buying, persisting beyond the still-evanescent if now-repeatable temporality of listening, and the promised stimulation and/or delusion of the consumer's ears. Clearly, these desires cannot easily be separated: in discs, the urge towards capturing the celebrity's body and the possibilities of listening to a voice are inextricably entwined. Yet, Caruso's case might indicate a larger pattern within the development of the gramophone industry, by which human capture provided the imaginative scaffolding for the aural orientations that could subsequently be claimed.Footnote 55

A chance remark – again taken from the pages of The Talking Machine World – demonstrates such bodily captivation. Quoted in an interview in late 1906, an anonymous ‘recording expert’ said: ‘No voice rings out better or with more realistic effect than Caruso's, and one could almost believe it was the man himself who was singing and not the record.’Footnote 56 Coming from inside the gramophone industry, these words – the earliest rumbling of the notion that the tenor's voice was especially suited to recording technology – can be read along with adverts for the special appeal of Caruso's discs to the ears. But the statement might also, and perhaps more straightforwardly, express admiration at the outcome of industrial processes of sonic sculpture: it conveys pleasure at the second self that ‘rings’ from record, even the disc that ‘sings’, with the greater emphasis falling not on the sensory means but on the industrial product, along with the act of recognition to which it gives rise.

The production of doubles had its political correlate in New York's colonia, as we have seen. Not only did settler-colonial racism split the world-famous celebrity from the lowly immigrant, the voice from its body, but it also created a biological tropology in which the split was given new shape, re-signified through two bodies linked by putative family ties. Splitting and doubling prepared the way for the singer's reproduction in sound: by loosening his voice from his body in advance of its circulation on disc; by readying listeners to receive the singer's double in his absence. There was, according to this prescription, a busy dialectic between Caruso's presence (on stage and in ‘real life’) and the absence materialised by his plastic doubles. In an obvious sense, discs stood in for the opera singer as a performer (as they once did when Conried first heard him in Paris), but they could also substitute for a fast-growing body of migrant southern Italians moving across the Americas.Footnote 57

Traces of this dialectic linger in Compton Mackenzie's words, quoted at the head of this article. Gramophone readers are enjoined to ‘test the measure of Caruso's vitality’: a life force that ‘made [the gramophone] what it is’. Behind this claim lay the prejudices of Old Europe against Italian excess, as well as more recent racisms inspired by a perceived overabundance of European migrants crossing the Atlantic.Footnote 58 Mackenzie invoked this political geography as follows:

There has recently been a tendency to decry Caruso for his over-emphasis, his shouting, his almost ventriloquial ambitions, his coarseness, and his theatricality. No doubt, his singing possessed all these faults; but they were the faults of superfluous energy, of superfluous emotion, of superfluous vitality. They were inherent in his personality and therefore in his art. He should have pruned his style, the critics tell us. No doubt he should; but it is easier to prune a gooseberry bush in a backyard than a jungle in Guiana.

Caruso's theatrical presence morphs into the thriving life of the tropics (distantly foreshadowing Werner Herzog's Fitzcarraldo); the colonial passagework is sudden and unashamed.Footnote 59 Mackenzie summoned Caruso as a power of mediatic propagation as vital and inevitable as the jungle's growth – a transition between the opera singer and the densely thicketed rainforest that could only make sense alongside a surplus of southern Italian lives driven around the sea.

For your ears only

At the time of his death, this much-vaunted vitality in Caruso's records was freshly recalled. There was an explosion of life-writing – newspaper articles, obituaries, biographies – which made passing mention of his recording activities, usually in the context of reports on his tremendous wealth.Footnote 60 A trope emerged of Caruso's ‘imperishable’ and ‘indestructible’ legacy in sound recordings, one summed up (and immediately capitalised on) in an Victrola advert that played on Caruso's deathlessness.Footnote 61 Less predictable and more variegated, however, was the picture that emerged from his earliest biography – the result of a collaboration between Pierre Van Rensselaer Key and Bruno Zirato, Caruso's lifelong personal secretary, rushed into print shortly after his demise:

Through ‘the machine’ (as he termed the phonograph) he was available to the multitudes who could by no other means feel the spell of his voice and art. It seems a fitting medium to help keep our memory of him fresh: we have only to close our eyes – listening to his reproduced singing – to have him almost with us.Footnote 62

Caruso's immortality offered the seed for a new kind of story about sound reproduction: one to do with countless, far-flung listeners, all enchanted by his voice alone. But it is worth noticing certain details. As Key invited his readers to close their eyes, he directed them not only in an act of listening but also in the reactivation of their memories. It was a graveside whisper to opera audiences rather than the untold multitudes: one that enjoined contemporaries to use recorded sounds as means to rekindle theatrical experiences of a well-loved singer.Footnote 63

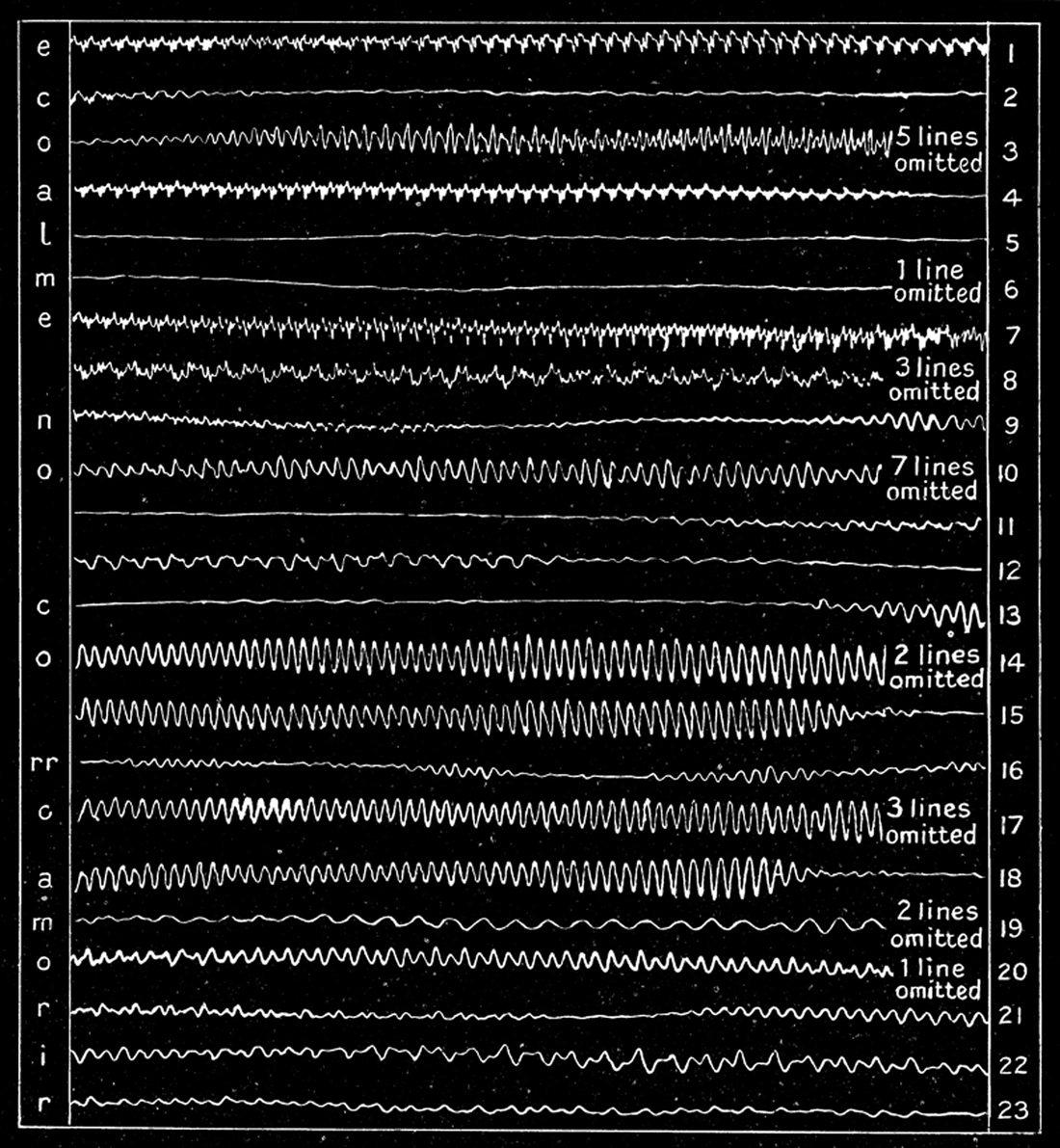

Another window onto the fast-changing meanings of Caruso's discs comes from the strange world of experimental phonetics. In 1924, a short vocal autopsy was published in The Musical Times by Edmund Wheeler Scripture, a speech scientist.Footnote 64 Scripture employed an experimental set-up he had honed over more than two decades: it consisted of a long, transducing arm connecting a needle – dragged through the groove of a slowly turning gramophone disc, rotating once every four hours or so – to a stylus pulled over scrolling black smoked paper. The result was an early spectrogram, mapping the frequency of sounds against their unfolding in time (Figure 3). By means of this contrivance, Scripture delivered his professional opinion on Caruso's vocal technique, as evidenced by the tenor's 1907 recording of ‘Di quella pira’, a widely known aria from Verdi's Il trovatore. His evaluation rested entirely on a 5-second passage near the end of the disc, with the onset of the aria's closing line, ‘teco almeno corro a morir’ (‘I'll hurry at least to die with you’).

Figure 3. An early spectrogram showing Caruso's voice, reproduced from Edmund Wheeler Scripture, ‘The Curves of Caruso’, The Musical Times 65/976 (1924), 518.

These words were a topical choice in the wake of Caruso's death. There is, of course, an exhibition value to the sustained, notoriously inauthentic high C (on ‘teco’); and the words provide a compact demonstration of all the Italian vowels (all except ‘i’ and ‘u’ appear twice, allowing for ease of comparison on the page).Footnote 65 What is more, there was a long tradition of wondering at powerful, manly Italian vowels in vocal pedagogy – a tradition to which Scripture contributes when he calls attention to the waveform's constant mobility of pitch:

[Caruso] does not sing the exact notes indicated by the music as an organ or other mechanical instrument would. His voice rises and falls and twists around the tones instead of sticking to them. The result is that the song has nothing mechanical about it, but is full of life and emotion.Footnote 66

However, Scripture's report also reveals the author's penchant for the macabre, a preference that dates back to his earliest experiments in transducing gramophone discs, when he focused on poetic declamations of ‘The Sad Story of the Death and Burial of Poor Cock Robin’. His aim had been to study the voice of the poet beyond the text: an almost animal, bodily presence that could be approached through discs in their physical, physiological and psychological dimensions. As described by Sterne, Scripture's writings are filled with pages ‘soaking in the metaphysics of presence’ – conviction in the identity between voice and being.Footnote 67 The result, in Scripture's autopsy of Caruso, is an analysis of the once-living voice staged through a text about rushing into the arms of death.

Odd though it is, Scripture's postmortem illustrates with unusual clarity the altered relationship between the tenor and his listeners, implying a new attention to aural tricks of ‘life and emotion’ the singer played on the ears following his demise. Scripture's approach is in this sense (if no other) emblematic of the retrospective impulses more broadly at work in the making of a musical medium: the imaginative and narrative structures that go hand in hand with listening techniques. We have seen how, in Mackenzie's short obituary, Caruso ‘made the gramophone what it is’ by interpellating the medium's listeners into being for the first time; in a more scientific register, Scripture likewise reimagined Caruso's discs in purely sonic terms, as if hearing the tenor's voice had always been their focus of attention, both the medium and the message.

Caruso continues to appear in contemporary scholarship when historians of listening move to emphasise the novel attractions and techniques entailed by gramophones – although nowadays he is more often taken to be symptomatic, rather than generative, of broader shifts.Footnote 68 In Sterne's celebrated history ‘audile technique’, for example, Caruso represents a larger moment in which North Americans began to use their ears in new ways.Footnote 69 Deriving from anthropologist Marcel Mauss's ‘les techniques du corps’, a 1930s coinage which has lately seen a resurgence, techniques of the body were ways of defining and dividing groups of people – by sex, age, ethnicity, and even premodern versus modern – according to the particular way they use their body and/or tools.Footnote 70 For Mauss, techniques of the body were culturally acquired, often the result of a ‘prestigious imitation’, and embedded within a ‘physio-psycho-sociological’ cluster of actions ‘assembled by and for social authority’.Footnote 71 On this view, Caruso, and by extension, opera, could have provided an important source of social authority for early gramophone listening – a novel object of attention for ears alone – offering sound scholars one ticket to an aurally inflected musical modernity.Footnote 72

Sterne's much larger goal, beyond his brief use of Caruso's example, was famously to challenge ocularcentric accounts of modernity – to show how aurality has been just as important as vision in the histories of the West – a vital aim that has been amply borne out by sound studies.Footnote 73 Yet, the rise of ‘audile technique’ leads into a historical aporia because, in practice, the sensory division of labour such specialisation implies is hard to sustain. Reading on in Scripture's autopsy can illustrate this basic difficulty; Caruso's voice, as an aural object, was difficult to keep in focus. The speech scientist pauses to wonder over line 8 of his diagram, which, ‘according to the text … must be a vowel curve, yet such a curve is an impossibility. It looked like a vowel curve produced by a violent wobbling of the tracing apparatus.’ Scripture goes on with easy authority to dismiss the idea that such an error could ever have been produced by his faultless experimental set-up. No, the ‘violent wobbling’ must emanate from the singer himself:

On listening carefully to the gramophone disc, I could hear that there was a difference in Caruso's voice at this point. He seemed to be crying. There was a tear in his voice, and this curve is the picture of a tear. How he did it, or how anyone can put a tear in the voice, is beyond imagination – but here is the registration of such a tear.Footnote 74

Scientific listening morphs into a séance: the disc becomes a vehicle by which a once-living body, even its internal vocal behaviour, might be recovered and examined. One day in the future, aided by still-greater powers of calculation, more mysteries might be revealed: ‘Still another secret of Caruso's voice – perhaps the most important one of all – lies in these curves. The melodious ring of his voice can be heard from the gramophone discs.’Footnote 75

Scripture was the first, though by no means the last, to summon Caruso from the grave.Footnote 76 He inaugurated a long tradition of autopsies and resurrections, both in voice science and in the music industry at large.Footnote 77 In presupposing a three-dimensional body impressed in, and forever-after able to be reanimated from, his discs, Scripture foreshadowed digital reconversion in the 1970s and beyond: the computational practices by which the voices of old singers are stripped of their noisy patina for the purposes of eternal exploitation in the marketplace.Footnote 78 Scripture thus marks an important development in Caruso's (now posthumous) career, in which he played the role not so much of a disembodied voice, but of something more like a ‘vocalic body’: one now significantly torn from the larger body of migrant southern Italians his voice once seemed to invoke.Footnote 79

But what Scripture most weirdly shows are the occult paths by which an aural orientation may be reached, and once reached, awkwardly maintained. This may be what the Caruso myth of listeners drawn to attend to the gramophone ultimately suggests: that ears are not easily directed to a man, or a technology, or even a particular technique of the body, at least not for long; they require the constant assistance of advertisers, exegetes, historians, speech pathologists, and more. Caruso's discs – like all discs – have never been a straightforward object of audition, never only directed to listening ears. They were and are a site for listening's entanglements: both the technical and always also the imaginative means by which it is assembled ever anew.

Acknowledgements

This article was written during a Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship at King's College London (2016–19). I would also like to acknowledge the support of Davide Ceriani, Olenka Kleban, Ellen Lockhart, Nicholas Mathew, Roger Parker, Ditlev Rindom, Mary Ann Smart and Flora Willson.