Globally, Indigenous peoples have developed and sustained food systems which have protected health, well-being and culture for tens of thousands of years(Reference Kuhnlein, Erasmus and Creed-Kanashiro1). Before Australia was colonised, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples maintained traditional, environmentally sustainable food practices and knowledge regarding ecosystems, food and water sources was passed down the generations through stories, paintings and ceremonies(Reference Sebastian and Donelly2,Reference Anderson, Fredericks and Brien3) . Many Aboriginal people view health as a concept that is ‘not just the physical wellbeing of an individual but refers to the social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of the whole community’(4). Food is essential for health and provides connections to land, culture, family and the past(Reference Thompson, Gifford and Thorpe5,Reference King and Furgal6) .

As with other Indigenous peoples internationally, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience unacceptable health inequalities. Compared with other Australians, life expectancy at birth is 10·6 years lower for males and 9·6 years lower for females; there has been no significant change in the gap in overall mortality rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians since 1998(7). The factors underpinning Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health include complex layers of socio-economic, historical and political determinants, including colonisation, dispossession and racism(Reference Sherwood8,Reference Mitchell, Carson, Dunbar and Chenhall9) .

More than two-thirds of the gap in morbidity and mortality between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous Australians is attributable to chronic diseases(10). Diet and high body mass are respectively responsible for 15 and 14 % of the gap in health outcomes(10). Furthermore, the prevalence of food insecurity is six times higher among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples than the non-Indigenous population(11).

Ambitious targets have been set for ‘closing the gap’ in health and social outcomes experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples(12). However, the contribution of food and nutrition to these health inequalities has been inconsistently reflected in policy over time(Reference Browne, Hayes and Gleeson13). There have been several national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policies and strategies(4,12,14,15) , with varying levels of commitment to improving food security and nutrition. Nutrition was notably absent from the $AU 1·6 billion National Partnership Agreement on Closing the Gap in Indigenous Health Outcomes (‘Closing the Gap’ hereafter)(16) agreed by Australian federal, state and territory governments in 2009(Reference Browne, Hayes and Gleeson13). Furthermore, where food and nutrition has been included as a priority in policy documents, resources for implementation have often been lacking(Reference Browne, Hayes and Gleeson13).

Translating policy ambition into tangible action requires political commitment. A growing body of research has examined how and why nutrition issues become priorities for governments(Reference Cullerton, Donnet and Lee17–Reference Balarajan and Reich19). However, little is known about factors determining political commitment to improving nutrition-related health outcomes for Indigenous peoples. In Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health is a discrete national policy area with a unique set of processes, actors, policies and financing arrangements. In order to inform public health advocacy, we sought to better understand the policy-making process in the field of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health over the last two decades. In the current case study of food and nutrition policy we asked: What were the key factors influencing the prioritisation of food and nutrition in national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy during the period 1996–2015?

Methods

Scope and setting

A qualitative policy analysis case study was undertaken to examine the prioritisation of food and nutrition in national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy. Policy analysis is a multidisciplinary field of research concerned with how issues are constructed as policy ‘problems’; why certain issues reach the policy agenda; and the ways in which governments pursue particular courses of action (or inaction) to address them(Reference Parsons20,Reference Walt, Shiffman and Schneider21) . The national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy subsystem, that is, the set of actors and institutions influencing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy, was selected as a case study of public health nutrition policy making in Australia.

Australia is a federation of six states and two territories. In 2016, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were estimated to represent 2·8 % of the Australian population(22). Although both the federal and state/territory governments have responsibilities in health policy, the study was concerned with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy making at the national level. This includes the policy decisions of the Commonwealth (national) Government as well as those of the Commonwealth-State/Territory intergovernmental forum known as the Council of Australian Governments (COAG).

Policy scholars suggest that time frames of ‘a decade or more’ are required to adequately study policy processes(Reference Sabatier23) (p. 3). The boundaries of the case study were 1996 and 2015 in order to facilitate a detailed investigation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy over two decades. These boundaries coincide with the transfer of responsibility for the administration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy to the Commonwealth Health Department (in 1995) and the publication of the first implementation plan for the current National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan (NATSIHP)(24).

Theoretical framework

Data collection and analysis were informed by theories of the policy process, addressing a common weakness of previous nutrition policy research(Reference Cullerton, Donnet and Lee25). Kingdon’s Multiple Streams theory(Reference Kingdon26), Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF)(Reference Sabatier27) and Shiffman and Smith’s policy analysis framework(Reference Shiffman and Smith28) were used to inform the study design and interpretation of the findings. These theories have been found useful for examining the prioritisation of nutrition on national policy agendas in Australia(Reference Baker, Gill and Friel18,Reference Cullerton, Donnet and Lee25,Reference Carey, Caraher and Lawrence29) .

Kingdon’s Multiple Streams theory posits that, at key junctures, ‘policy windows’ provide an opportunity for skilful actors called ‘policy entrepreneurs’ to match problems and policy solutions in a favourable political climate(Reference Kingdon26) (p. 20). It is the coupling of problems, policies and politics at opportune moments that increases the likelihood of an item being elevated onto a government’s agenda. This theory was used to inform the interview design and data analysis and assisted interpretation of the research findings.

The sampling strategy was informed by the ACF, a theory for analysing policy change at the subsystem level(Reference Sabatier27). Policy subsystems comprise actors who specialise in that policy area, including politicians, public servants, interest group leaders, researchers and journalists(Reference Sabatier, Weible and Sabatier30). According to the ACF, these actors aggregate into coalitions based on shared beliefs and coordinate their activities to influence the policy subsystem(Reference Jenkins-Smith, Nohrstedt, Weible, Sabatier and Weible31). The ACF also recognises that external factors, such as changes in socio-economic conditions, elections and policy decisions in other subsystems, may influence opportunities for policy change within the subsystem(Reference Sabatier27), which coalitions may exploit in a similar manner to Kingdon’s ‘policy windows’(Reference Kingdon26).

The Shiffman and Smith framework(Reference Shiffman and Smith28) has been applied to examine the prioritisation of nutrition policies in low- and middle-income countries(Reference Balarajan and Reich19,Reference Pelletier, Frongillo and Gervais32–Reference Lapping, Frongillo and Studdert36) . More recently, Baker et al. applied this framework to examining the factors generating and constraining political priority for obesity prevention interventions in Australia(Reference Baker, Gill and Friel18). Thus, this provides a useful framework for analysing the prioritisation of food and nutrition in the current case study.

The framework consists of four categories of factors determining political priority. The first category, ‘actor power’, evaluates ‘the strength of the individuals and organisations concerned with the issue’(Reference Shiffman and Smith28) (p. 1371). ‘Ideas’, the second category, emphasises the social construction of policy problems by actors(Reference Shiffman37). The framework differentiates between ‘internal’ framing (agreement among the policy community regarding the problem and its solutions) and ‘external’ framing (the portrayal of the issue to political leaders and the general public)(Reference Shiffman and Smith28). The third category focuses on the ‘political contexts’ in which policy actors operate. These include governance structures as well as Kingdon’s concept of policy windows(Reference Kingdon26), which advocates must exploit to reach political leaders. The final category, ‘issue characteristics’, examines features of the health problem, such as its severity and the availability of evidence-based solutions.

Data collection

The present policy case study combined multiple sources of data, as is recommended to enhance rigour in case study research(Reference Yin38,Reference Baxter and Jack39) . The research reported here was part of a larger project which combined three document collection studies(Reference Browne, Hayes and Gleeson13,Reference Browne, de Leeuw and Gleeson40,Reference Browne, Gleeson and Adams41) with key informant interviews in order to illuminate policy processes in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. Data collection for the present study consisted of semi-structured, in-depth interviews, which were supported by a review of key documents. The purpose of document collection was to build a record of the events and processes in the development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy. Informed by the ACF, documents were sampled from the websites of organisations involved in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy. These included Government agencies, advocacy organisations, universities and media outlets. Academic and media articles were also retrieved through searching relevant databases (e.g. Medline, Factiva, Google Scholar).

Documents collected included Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy documents, implementation plans, evaluation reports, discussion papers, submissions, research reports, budget papers, media releases and news articles. Criteria for selecting documents were that they must be publicly available; published between 1995 and 2015; and relevant to one of three policy episodes: the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nutrition Strategy and Action Plan (NATSINSAP)(42), Closing the Gap(12,16) or the NATSIHP(15). Document review was used to inform the interview questions and corroborate findings from key informant interviews.

Semi-structured interviews were undertaken with stakeholders involved in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and/or nutrition policy between 1996 and 2015. Purposive sampling, informed by the ACF, was used to identify individuals who could provide information about the policy processes under investigation, including politicians, advisors, public servants, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health leaders, nutrition/health promotion practitioners, academics and journalists. Names of potential interviewees were identified from publicly available documents and recommendations by interview participants.

Fifty individuals were invited to participate. Wherever possible, Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander stakeholders were invited in order to capture the views of the people most affected by these policies. Potential interview participants were approached via email. A follow-up email was sent if a reply was not received within one month.

Thirty-eight policy stakeholders from a range of sectors agreed to participate (response rate 76 %). Fifteen participants (39 %) were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander (Table 1). Interviews were undertaken between September 2015 and March 2017, with the majority (n 34/38) conducted in person (n 3/38 were conducted by telephone, n 1/38 provided responses via email) and an average duration of 71 min. Interviews were audio-recorded (with permission) and transcribed. Participants were emailed copies of their interview transcripts and provided the opportunity to amend their responses.

Table 1 Characteristics of interview participants: key actors involved in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy between 1996 and 2015, Australia (n 38)

The study was conducted according to the guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number 14-059). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research(43) were also followed.

Data analysis

Documents were stored chronologically in electronic folders created for each policy episode and sorted by document type. These documents were used to build a timeline of key events and processes that contributed to the development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy between 1996 and 2015. A detailed, temporal narrative of each policy episode was prepared and checked for accuracy with the project Advisory Group. According to Bowen(Reference Bowen44) (p. 29), the value of document collection in case study research ‘lies in its role in methodological and data triangulation’. Information gathered from document analysis was corroborated and explored in further detail through key informant interviews, through an iterative process of constant comparison, in order to construct a rich and robust case study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nutrition policy.

Interview transcripts were entered into the qualitative research software NVivo version 11. Data analysis followed the five stages of qualitative data analysis described by Pope et al.(Reference Pope, Ziebland and Mays45). After initial familiarisation, interview transcripts were systematically coded line by line. Topic coding was used to label key subjects and ideas and analytic coding was used to develop new categories and themes from the data(Reference Morse and Richards46). A subset of transcripts (n 7) were also coded by the second author to ensure consistency. Agreement on key codes and categories was reached through discussion. The coding framework was then applied to the remaining transcripts.

Themes were generated through an iterative process of linking key concepts in the data with the theories of the policy process described above. While themes were identified inductively, those related to advocacy coalitions and to the ‘problems’, ‘policies’ and ‘politics’ indicators of Multiple Streams theory were actively pursued. Themes were mapped to the Shiffman and Smith framework and additional emergent themes were identified to produce a new conceptual framework. The results of the analysis were presented to the project Advisory Group who provided feedback on the interpretation of findings.

Results

Table 2 provides an overview of the themes derived from the data, organised under the categories of actor power, ideas, political contexts and issue characteristics. A fifth category, ‘the rise and fall of nutrition’, presents the results of document analysis along with participants’ perceptions regarding the extent to which nutrition has been prioritised in national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy between 1996 and 2015. In the following, participant codes and types are shown in brackets following each quotation. Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander participants are indicated by participant codes beginning ‘AP’.

Table 2 Thematic framework derived from interviews with policy actors involved in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy between 1996 and 2015, Australia (n 38) (adapted from Shiffman and Smith(Reference Shiffman and Smith28), p. 1371)

The rise and fall of nutrition

A timeline of key Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policy events that occurred over the period under investigation was prepared based on document analysis (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Files 1–3). This temporal analysis of the prioritisation of food and nutrition was further discussed by interview participants.

There was a general consensus among participants that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nutrition policy was most prominent on the national agenda in the late 1990s to the mid-2000s. One participant described this as ‘the golden era’ (AP20, academic). Participants described high levels of both political and community interest in food and nutrition at this time. Importantly, a national strategy (NATSINSAP) was in place, as well as a specific workforce in some states to deliver nutrition activities.

Participants reported that nutrition had struggled to gain political prominence and had receded from the policy agenda in recent years, both as a public health issue in general and in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. One participant described nutrition and physical activity as the ‘poor cousins’ (P15, public servant) to other public health issues viewed as higher political priorities, such as immunisation and tobacco control.

Actor power

Participants reflected on the extent to which the different actors involved in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and nutrition had influenced the national policy agenda. The key elements of actor power identified by participants were the need for a collective voice, policy ‘champions’, an institutional home and building a groundswell through civil society mobilisation (Table 2).

Participants described how, in order for an issue to receive policy attention, the key players needed to be united in their lobbying and speak with a collective voice, because ‘collectiveness around it gives it weight’ (AP27, Aboriginal health leader). However, several participants reported that the stakeholder group working in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nutrition was more cohesive in the 1990s–early 2000s than the later decade studied.

By the late 2000s, some participants reported the nutrition policy community had become fragmented. The National Public Health Partnership, which had served as a guiding institution for public health nutrition policy, was disbanded in 2006. Furthermore, several nutrition and health promotion units within state governments had been restructured, with staff made redundant or moved to different areas. It became difficult to maintain a cohesive policy community as ‘the people that you need to pull together to make a difference are too disparate’ (P21, public health nutritionist). Another participant reflected on the recent lack of coalescence within the nutrition policy community, indicating that although much was happening, ‘it hasn’t come together’ (AP27, Aboriginal health leader) in the way that activity on other public health issues had.

According to participants, ineffective leadership was another reason why nutrition was low on the policy agenda. The need for ‘champions’, and particularly Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership, was noted by almost all interview participants. The lack of ‘Aboriginal leadership at a very public level’ (P4, public health nutritionist) was considered by some to be a key reason why nutrition had not gained traction in recent years, along with a shortage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nutrition professionals. Furthermore, several participants indicated that nutrition practitioners were not viewed as influential leaders in policy debates, and some suggested that the female-dominated nutrition workforce also had an impact. For example, one participant said, ‘[Nutrition is] sort of seen to be women’s business and not important’ (P2, public health nutritionist).

Some participants suggested that nutrition advocates had struggled to mobilise civil society actors in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nutrition advocacy. Specifically, as one participant noted, the organisation representing the Aboriginal Community Controlled health sector, NACCHO, had limited capacity to participate in nutrition advocacy and had other pressing priorities. Conversely, key nutrition advocacy organisations, such as the Dietitians Association of Australia and the Public Health Association of Australia, were noted as absent from the Aboriginal-led civil society campaign for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health equality called Close the Gap.

Ideas

The perceptions of policy actors about ideas were grouped into two themes. The first theme, the ‘internal frame’, is about the perceived lack of consensus among food and nutrition advocates. Second, the ‘external frame’ highlights the need for a compelling narrative to communicate policy ideas to decision makers.

Interview participants suggested that the framing of nutrition issues required further attention in order to generate public and political interest. For example, several participants reported a lack of consensus within the nutrition community about both priority issues and appropriate policy responses. Nutrition advocacy was described as ‘a chorus of voices talking about a range of solutions’ (P31, political advisor) and ‘a lot of noise but no consistent messages’ (AP22, public health nutritionist).

Constructing a compelling narrative for improving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nutrition was seen as essential to positioning nutrition as a policy priority. Participants noted that some areas of health policy had advocates who were able to articulate a compelling ‘pitch’ to Government about ‘what the facts are, what the benefits are and what they’re actually seeking’ (P32, political advisor). Several participants suggested that nutrition advocates, on the other hand, had not managed to articulate a clear ‘call to action’. The importance of a compelling argument to advance nutrition policy was summarised as follows:

‘Nutrition policy […] struggles at times because there’s not a very compelling narrative: if you do x, y and z with this amount of resource, this is the health benefit.’ (AP7, academic)

Political contexts

Policy actors described how the political environments in which they operated influenced whether or not health issues, such as nutrition, received priority. These included governance structures within the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and/or nutrition sector and the opening of policy windows. Within these two themes, interview participants raised several political opportunities and challenges relevant to the prioritisation of food and nutrition.

Participants noted that during the 1990s, food and nutrition was on the agenda, more broadly, within the Australian Government and internationally. A National Food and Nutrition Policy had been published in 1992, and Australia contributed to the World Declaration on Nutrition in the same year. The Australian Government also backed the formation of a Strategic Intergovernmental Nutrition Alliance (SIGNAL), to develop an implementation strategy for its National Food and Nutrition Policy and a specific Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nutrition strategy. This institutional support for nutrition policy was key, as this participant described:

‘So you can really see this clear, linear process between some countries like Australia, would you believe, being a leader in development of national nutrition policy. And then WHO picking up and saying “everybody should do this”.’ (P2, public health nutritionist)

Many participants reported that the Commonwealth Government’s commitment to public health had declined over time. Furthermore, within public health, nutrition ‘didn’t have any political prominence’ (P8, public servant). This shift away from public health had direct implications for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy, as it meant that the focus for investment would be on health services rather than preventive health. Participants also suggested that political ideology impacted the priority governments give to nutrition policy. These participants reported that governments preferred approaches based on personal responsibility and ‘free market enterprise and health education’ to public health approaches, which ‘smacks of big government’ (P4, public health nutritionist).

The development of the NATSIHP during 2012–13, and its implementation plan in 2014, was the most recent window, mentioned by participants, for influencing the policy agenda. While Aboriginal health leaders and organisations were actively engaged during the development of this policy, nutrition advocates were not particularly involved, with few making submissions during the consultation process. Participants noted that nutrition did not feature prominently in the document, possibly due to ‘missed opportunities’ (P3, academic).

Issue characteristics

The characteristics of nutrition as a policy issue were perceived to present particular challenges for policy makers and health advocates. Thus, notwithstanding the political, institutional, discursive and relational barriers outlined in the previous sections, policy actors suggested that nutrition may be a difficult issue to prioritise for a number of reasons. Issue characteristics derived from the interview data were grouped into three key themes: ‘nutrition is many things’; ‘its severity (relative to other issues)’; and ‘there’s no simple solution’ (Table 2).

Participants commented that the nutrition issues requiring government attention span several programme areas, including child development, bush foods, chronic disease and food security. Interviewees suggested that because nutrition is a multifaceted and complex policy area, any focus on it is easily diffused across the silos of government. The multifaceted nature of nutrition also makes it difficult to measure and there is no single metric to monitor nutritional status in the population.

In contrast, tobacco became a much more compelling policy issue in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health over the decade studied. A key report, the Indigenous Burden of Disease Study, stated that smoking was the single biggest factor in the gap in health outcomes between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous Australians. Many participants considered this piece of research, and the compelling, quantitative evidence provided, to be one of the key drivers for the significant COAG investment in tobacco control. One participant recalled:

‘It sort of overtook everything, the smoking stuff […] It became the thing that everyone concentrated on but that meant things like nutrition dropped off.’ (AP19, public servant)

Almost all participants described the complexity of nutrition policy and the absence of simple solutions as an important barrier to policy action. This is especially challenging when ‘the golden rule in lobbying is don’t ever present a problem without also having the solution’ (P31, political advisor). Participants suggested that the complex, multifaceted nature of nutrition made it more difficult for governments to address compared with tangible medical issues.

The limited evidence base for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nutrition policy was seen as another barrier. Despite demonstrating quantifiable outcomes of interventions and a ‘positive return on investment’ (P31, political advisor), many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nutrition programmes have not been published in the peer-reviewed literature. Conversely, the evidence and logic for investing in tobacco control was much clearer. As a result, other issues competing for a place on the health policy agenda have received greater attention. The challenge of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nutrition advocacy is summarised as follows:

‘So you’ve got a problem, which is a bit tough because it’s different issues, it’s not in your face, it doesn’t have a single group advocating for it and it doesn’t have a single, neat solution.’ (P17, public servant)

Discussion

Although there is a considerable body of research in the field of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nutrition, the present study may be the first to examine national policy processes in this field. Interviews with stakeholders who had been directly involved in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy revealed key factors underpinning the changing position of food and nutrition on the national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy agenda over 20 years. These findings provide lessons about health advocacy which may be used to advance Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nutrition and other priority health issues.

Factors which may have enabled the prioritisation of nutrition during the late 1990s and early 2000s include the coalescence of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nutrition policy community and an enabling political and institutional environment. The barriers which contributed to nutrition falling off the agenda in more recent years include the complexity of nutrition as a policy problem and the perceived lack of a simple, evidence-based policy solution. Additionally, the policy community has lacked unity, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership, an institutional home and a compelling policy narrative. Overcoming these barriers and harnessing the enablers will be crucial to advancing food and nutrition policy in the future.

According to Shiffman and Smith, health issues that are more likely to attract political priority are easily measured, cause substantial harm, and have simple, cost-effective, evidence-based solutions(Reference Shiffman and Smith28). The complex, multifaceted nature of the policy ‘problem’ and the lack of a simple ‘solution’ were identified in the present research as key barriers to progressing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nutrition policy. These challenges have been recognised as barriers to progression of nutrition policy in the broader Australian context(Reference Cullerton, Donnet and Lee17,Reference Baker, Gill and Friel18,Reference Crammond, Van and Allender47) .

The need to vie for scarce resources with many other pressing health issues is a key challenge for public heath nutrition. According to bounded rationality theory, policy makers have limited capacity to process information(Reference Jones48) and, therefore, will consider only a small number of policy problems at any given time(Reference Zahariadis, Sabatier and Weible49). This results in competition between interest groups, which in the context of tobacco, nutrition and physical activity has been dubbed ‘risk factor envy’(Reference Yach, McKee and Lopez50) (p. 900). Our findings suggest that risk factor envy was also a challenge in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health context, particularly with regard to the prioritisation of tobacco control over nutrition.

A key factor influencing the higher priority given to tobacco control was the publication of the Indigenous Burden of Disease Study, which positioned tobacco as the leading contributor to the health gap(Reference Vos, Barker and Begg51). This has been reported in other studies of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy processes(Reference Vujcich, Rayner and Allender52,Reference Katz, Gajjar and Zwi53) . For example, presentation of the Indigenous Burden of Disease Study’s findings to policy makers at Parliament House was found to be instrumental in the prioritisation of tobacco control(Reference Vujcich, Rayner and Allender52). Furthermore, the observation that many policy documents, including the Closing the Gap agreement and the NATSIHP, cited the Indigenous Burden of Disease Study(Reference Doran, Ling and Searles54) further highlights how skilful provision of evidence to decision makers facilitates policy attention to a health issue.

A barrier to incorporating nutrition strategies within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy, identified in the present research, was the limited evidence base to guide policy action. This finding is consistent with previous research about the formulation of nutrition policy in Australia(Reference Baker, Gill and Friel18,Reference Jones48,Reference Nathan, Develin and Grove55–Reference Shill, Mavoa and Allender57) . However, it is also clear that values, ideology, public opinion, lobbying and economic interests may be equally important, if not stronger, drivers of policy than evidence(Reference Cullerton, Donnet and Lee17,Reference Carey, Caraher and Lawrence29,Reference Clarke, Swinburn and Sacks58–Reference Bowen, Zwi and Sainsbury60) . Significant Government investment in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tobacco control occurred in the absence of high-quality evidence for the effectiveness of such interventions(Reference Vujcich, Rayner and Allender52). Therefore, a limited evidence base, alone, should not preclude nutrition from being incorporated into Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy.

A key finding of the present study was that there is a perception among policy actors that nutrition advocates have not constructed a compelling narrative and ‘call to action’. Furthermore, lack of consensus regarding the framing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nutrition has further constrained public and political support. While academics and practitioners working in the field are united in their belief that nutrition is important, a clear and coherent ‘story’ to define the causes of and solutions to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nutrition issues has been missing. Shiffman and Smith(Reference Shiffman and Smith28) argue that both internal and external framing are important for generating political priority. Disunity within the nutrition community has previously been highlighted as a barrier to advancing nutrition policy in Australia(Reference Baker, Gill and Friel18,Reference Cullerton61) . However, this is the first time that it has been identified in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health context.

According to Multiple Streams theory(Reference Kingdon26,Reference Kingdon62) , for an issue to be prioritised on the governmental agenda, three processes must converge. First, the issue must be recognised as a problem requiring government action. Second, effective, technically feasible policy solutions need to be generated. Some of the challenges associated with generating such evidence about nutrition ‘problems’ and ‘solutions’ are described above. Third, even if credible problem indicators and evidence-based policy ‘solutions’ exist, the political environment in which advocates are operating must be favourable in order for policy proposals to gain priority(Reference Kingdon26,Reference Shiffman and Smith28) .

The present study revealed several political challenges to advancing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nutrition on the policy agenda. These included changes to institutional and governance arrangements and the neoliberal preference for an ‘individual responsibility’ approach to nutrition policy. Kingdon(Reference Kingdon26) (p. 20) argues that if skilful advocates (policy entrepreneurs) are able to recognise opportunities in the political environment, they can push their ‘pet proposals’ onto the agenda by ‘coupling both problems and solutions to politics’. Taking advantage of these ‘policy windows’ is essential for generating political priority for health issues(Reference Shiffman and Smith28) (p. 1372). The present study’s findings suggest that nutrition advocates have not sufficiently capitalised on policy windows and that policy entrepreneurship has been lacking.

The present study has identified factors which may facilitate greater political priority for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health issues, such as nutrition. While data and evidence are important, generating political priority requires technical information to be translated into a compelling narrative and collectively voiced by united advocacy coalitions. Strong advocacy requires coordination through an institutional home base, civil society mobilisation and an understanding of political contexts and policy windows so that opportunities for policy change can be seized. Finally, while improving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health should be a priority for all Australians, the present study highlighted the critical importance of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership in nutrition advocacy.

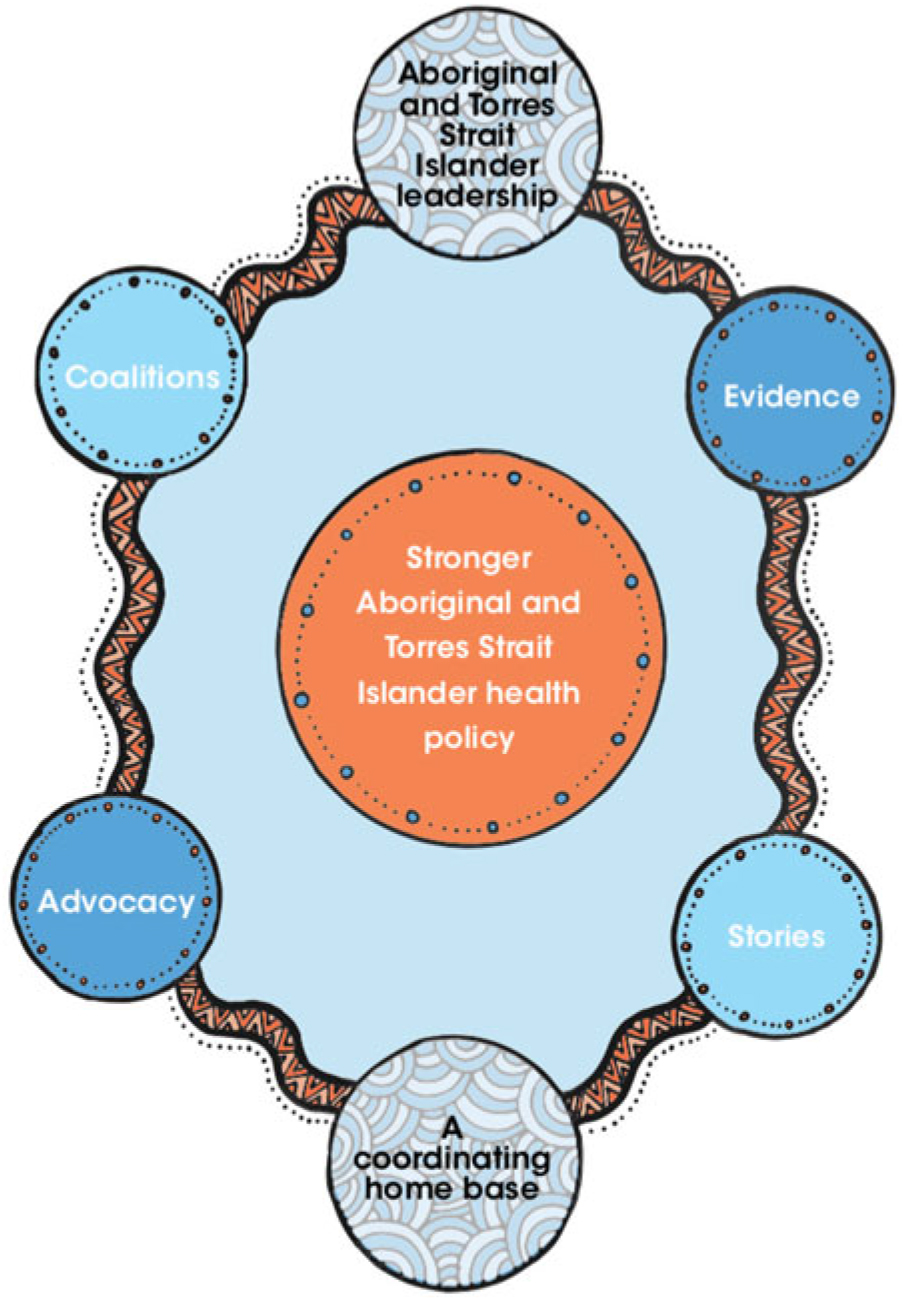

The results from the present study were combined with key concepts from the policy theories underpinning the research to produce a new conceptual framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health advocacy (Fig. 1 and Table 3). This empirically derived, theoretically informed framework outlines strategies that advocates could pursue in order to facilitate stronger Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy. Although this framework was synthesised from the present research on nutrition policy, it is underpinned by policy process theories and the terminology was informed by the project Advisory Group. Therefore, it is likely to be applicable to other areas of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wider public health policy.

Fig. 1 (colour online) Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health advocacy

Table 3 Relationship between the new framework, study findings and policy theories

Limitations

The current study has several limitations. Although a variety of stakeholders were interviewed, it was difficult to recruit some participants, particularly politicians and stakeholders involved in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy in the 1990s. The long time frame used in the research increased the chance of recall bias, and some stakeholders declined the invitation to participate because they felt they would not be able to remember details of past events. Additionally, some participants employed by government were restricted in their capacity to answer questions due to the codes of conduct for public servants. Similarly, some government documents which would have been useful data sources were not publicly available. To mitigate these risks, the present research findings are based on the corroboration of evidence from multiple sources and kinds of data.

The research identified factors which were perceived to influence Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy, but was not able to determine their relative importance. The inability to identify how much each variable contributes to a particular outcome is a limitation of case study research(Reference George and Bennett63). Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn about the causal significance of any of the factors identified in the present research, other than that they collectively appeared to be important.

Conclusion

The present study identified key factors likely to have facilitated or impeded the political attention to, and support for, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nutrition over 20 years. Future advocacy should focus on embedding nutrition within holistic approaches to health and building a collective voice through advocacy coalitions with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership. Strategic communication and seizing political opportunities may be as important as evidence for raising the priority of food and nutrition, both within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health as well as wider public policy.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: This research was undertaken on Aboriginal land. The authors wish to acknowledge the invaluable contribution made to the research presented herein by the members of the Advisory Group: Dr Mark Lock, Summer Finlay, Petah Atkinson, Lyn Dimer, Sharon Thorpe, Nicole Turner, Lang Baulch and Dr Vanessa Lee. The artwork in Fig. 1 was provided by Shakara Montalto. The research team also wants to acknowledge and thank all of the people who participated in the interviews, which were central to this research. Financial support: This research was funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council Postgraduate Research scholarship (J.B., grant number GNT1093011). The National Health and Medical Research Council had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: J.B. conceptualised the study with input and supervision from D.G., K.A., D.M. and R.H. J.B. collected the data. J.B. and D.G. analysed the qualitative data under the supervision of R.H. and with assistance from K.A. and D.M. J.B. drafted the manuscript and all authors provided critical review. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number 14-059). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research were also followed.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019001198