The National Service Framework for Mental Health (Department of Health, 1999) and the NHS Performance Ratings 2003/2004 (Healthcare Commission, 2004) consider patient experience to be a key performance indicator in mental health services. The method of choice for assessment of patient experience is the evaluation of patient satisfaction, primarily using surveys (Department of Health, 2000; Healthcare Commission, 2004). Unfortunately, despite the growing popularity of patient satisfaction as a measure, there has been surprisingly little attention paid to examining what the concept actually means. Powell et al (Reference Powell, Holloway and Lee2004, p. 17) state that evaluation of patient satisfaction in mental health has been mostly ‘ theory-free, assuming incorrectly that the concept of satisfaction is transparent and unproblematic’. There are specific theoretical concerns regarding the concept of patient satisfaction in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and these include the possible distorting effects of insight, delusions and interpersonal mechanisms such as transference (Reference LebowLebow, 1982). The objective of this research was to use qualitative methodology to examine the concept of patient satisfaction in people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia in the context of a recent in-patient admission.

Method

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee, University Hospital, Nottingham, and ten participants were recruited. All the participants had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and had been discharged from an acute adult in-patient ward in Nottingham within the past year. A ‘ theoretical sampling’ strategy ensured that the sample comprised participants admitted voluntarily and detained under the Mental Health Act 1983. Of the ten participants, six were male and seven were detained under the Mental Health Act 1983 during their most recent admission. The ages of the participants ranged from 20 to 54 years, and the number of previous admissions ranged from 0 to 20. Nine of the participants identified their ethnicity as White British and one as African-Caribbean.

One researcher (R. D.) conducted all the interviews at a venue chosen by the participant, usually the home. The interviews followed a depth interview format and the researcher encouraged each participant to relate, in their own terms, experiences and attitudes. The interviews were aided by a brief interview guide containing three prompts: demographic details, history of contact with mental health services and experiences around in-patient stay. The interviews lasted between 40 and 110 min, with an average duration of 65 min.

The analysis ran concurrently with the data collection and this allowed the teasing-out of emerging themes in later interviews (part of the analytical induction process). The validity of the analysis was increased by collaboration between the researchers in the analysis of the transcripts.

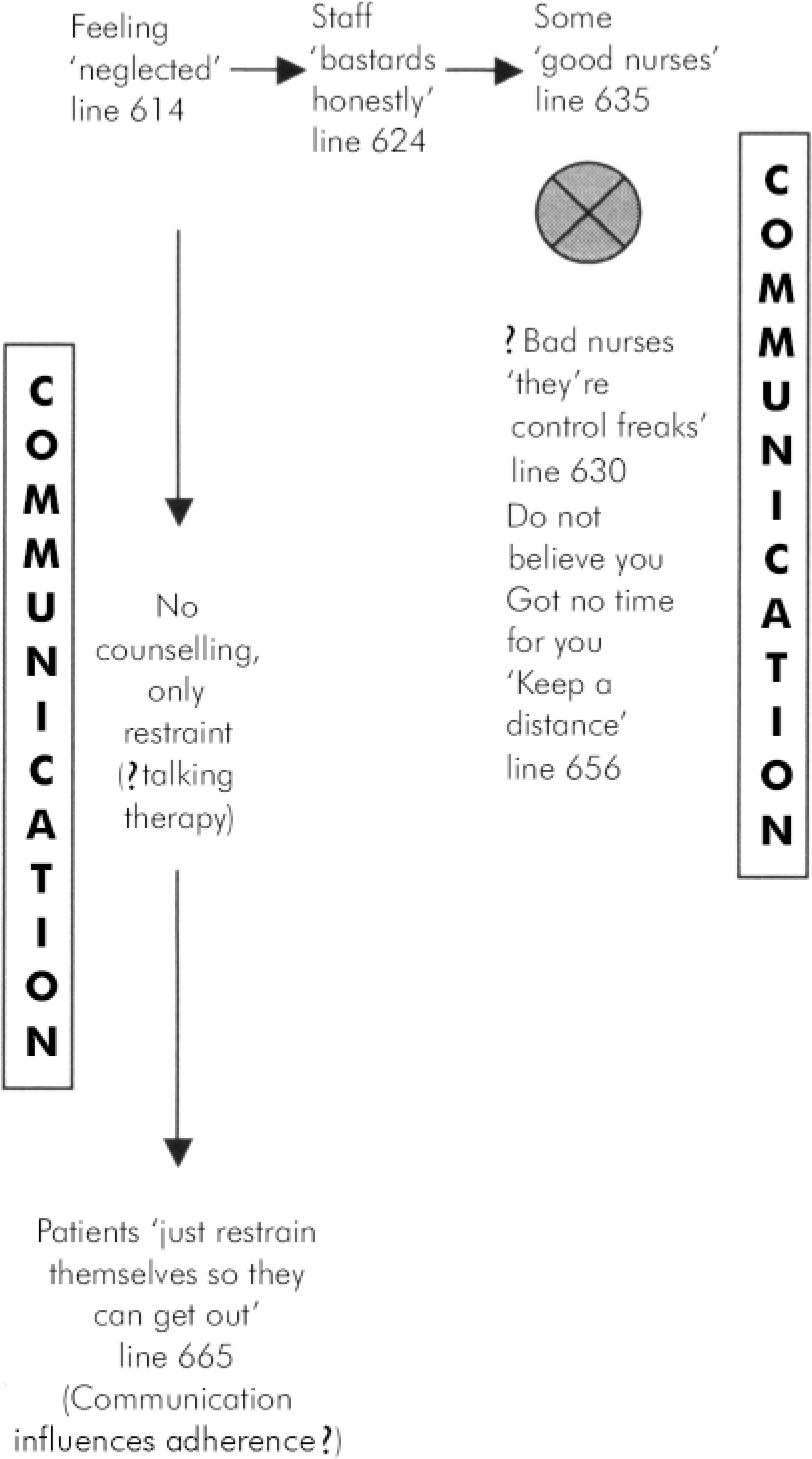

The tool used for the qualitative data analysis was cognitive mapping (Reference Jones and WalkerJones, 1985). Cognitive mapping is a method of modelling a person's beliefs in diagrammatic form and seeks to represent a person's explanatory and predictive theories about those aspects of their world being described. An overview diagram of part of a map is provided in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Example of an extract from a cognitive map. The plain text represents descriptions of entities by the participant and appropriate direct excerpts from the transcript. The arrows represent possible causal links between entities. The crossed circle represents a ‘bipolar link’ in which an entity has been elaborated by contrasting it with explicit or implicit psychological alternatives. The text in parentheses indicates inferences and interpretations made by the researcher. The boxed text indicates a possible evolving category that, in this case, is communication.

The cognitive mapping process was followed with each interview and the resultant analyses were compared. Themes became apparent that were closely related to the original category labels. In working towards the themes, analytical induction was used to increase the validity of the analysis (Reference ShawShaw, 2000).

Results

The analysis identified two themes that influenced the expression of patient satisfaction with the recent inpatient admission: external factors and internal factors.

External factors

In this theme, four key categories of service provision were identified: fear of violence, communication with staff, lack of autonomy and ward routines.

Fear of violence

A fear of potential violence from other patients on the ward appeared to reduce satisfaction:

‘9 times out of 10 whenever I’ve been admitted or admitted myself there are people that are physically violent, threatening towards other people’ (Mr K. line 304).

‘Scores of times of being in hospital where I’ve seen patients being violent. I just want to go up to them and say oh sweetheart don't do that, you are doing the wrong thing. But I am afraid’ (Mrs G, line 223).

Fear of violence was a factor in all of the interviews. This fear often led the participants to hide in their bedroom or want to discharge themselves.

Communication with staff

All of the participants reported that communication with staff was important in determining their satisfaction with in-patient services. Participants were dissatisfied with the lack of explanation of ward procedure and facilities, and perceived that staff prioritised clerical work over communication:

‘It would have been a lot, a lot easier for me if they had of given some kind of induction. Because when I got there basically its just they showed me where to smoke and where to sit and watch TV and showed me my room and that was it. They went off and did their thing and I was left to just wander about basically’ (Mr F, line 222).

The satisfaction with an individual nurse or doctor was often related to that staff member's willingness to communicate:

‘I used to see one member of staff by herself and I used to have a good chat with her and I found that helpful. One-to-one. Because I could express myself a bit more and she’d understand’ (Mr E, line 791).

Lack of autonomy

The majority of participants described a sense of lack of autonomy and powerlessness while on the wards:

‘It's like being a sausage in a sausage machine, put in one end, processed, and put out the other’ (MrA, line 564).

‘Well you get used to it after years of being in a psychiatric hospital, people run your life for you. You don't run your own life’ (Ms J, line 872).

Five of the participants felt that in-patient wards were like prisons, and they were treated like criminals.

Ward routines

The participants were dissatisfied with ward reviews, queuing for meals, ward activities, and mixed-sex wards. Ward reviews with the multidisciplinary team were described as ‘frightening’ (Mr E, line 754) and ‘ upsetting’ (Ms J, line 435). Queues for meals were seen as flash-points for violence. All the female participants preferred single-sex wards because of perceptions of violence and sexual harassment on mixed wards.

Internal factors

This theme encompassed factors linked to the participants’ conceptions of their mental health, and their expectations of mental health services. Conceptions and expectations appeared to be linked to a participant's personal lay understandings, and in the case of some conceptions also to possible psychotic beliefs.

Satisfaction was decreased when a participant's conception of their condition was perceived to be different from the staff's conception:

‘From a Christian point of view, I try to look at it as something spiritual or a spiritual experience. I could have dealt with it from that angle, but because I was pulled out of that sort of environment, and put into another, one where the emphasis was on the treatment, and like the medication’ (Mr A, line 706).

‘I felt that my illness isn't what they named it. I did black magic myself and I got possessed. I didn't tell anybody that. Well they said I was suffering from schizophrenia. But I know I’m not… I wanted help from the church to exorcise the spirit’ (Mr E, line541).

Low expectations of psychiatric services tended to increase satisfaction. For example, the absence of psychological therapies during an in-patient admission did not decrease satisfaction because there was not an expectation that these could be offered in such a setting.

‘I would’ve liked someone to talk to, but that's psychology, you don't expect it on the ward. The ward is psychiatry, you know medicines’ (Mr A, line 1064).

Discussion

A number of existing studies, using a variety of different methodologies, confirm the findings of this small study. A quantitative study found that 30% of patients believed the ward environment to be unsafe or frightening (Reference BarkerBarker, 2000), and this is a finding in other qualitative studies (Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, 1998). Qualitative and quantitative studies have stressed the importance of communication in determining satisfaction (Reference WeinsteinWeinstein, 1981; Reference Goodwin, Holmes and NewnesGoodwin et al, 1999), and the Mental Health Act Commission (1997) reported that in 38% of wards there was no contact with patients other than observation. Studies using varying methodology have stressed the value patients place on autonomy (Reference McIntyre, Farrell and DavidMcIntyre et al, 1989; Reference RoseRose, 2001), and researchers have likened in-patient wards to prisons for decades (Reference GoffmanGoffman, 1968; Reference Goodwin, Holmes and NewnesGoodwin et al, 1999). Dissatisfaction with ward reviews and ward activities has been stressed in several studies (Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, 1998; Reference Goodwin, Holmes and NewnesGoodwin et al, 1999). The influence of patient conceptions on satisfaction has been hypothesised (Reference Rogers, Pilgrim and LaceyRogers et al, 1993), and previous research has suggested a relationship between expectations and satisfaction (Reference Williams, Coyle and HealyWilliams et al, 1998).

Although a number of measures were taken to increase the validity of this study (including the clearly defined analysis technique, the involvement of both researchers in the analysis, and the use of analytic induction), the small size of the sample and the method of recruitment mean that caution should be taken in generalising our findings. Goodwin et al (Reference Goodwin, Holmes and Newnes1999) described 13 themes that patients feel influence their views on inpatient services, and these themes are reflected in our themes and categories, except for the theme of dissatisfaction with medication, particularly side-effects. The use of a psychiatrist as the interviewer in our study may have biased responses and contributed to this discrepancy. A qualitative study in the USA suggested that the therapeutic relationships with other patients on the ward are a major determinant of satisfaction (Reference Lieberman and StraussLieberman & Strauss, 1986). The absence of such a finding in this and other UK studies suggests that therapeutic community principles, utilising patient relationships in recovery, are more prevalent in the USA.

A hypothesis that can be formulated from our study is that the relationship between the concept of patient satisfaction and patient experience is complex, and is influenced by both external and internal factors. Patient satisfaction with in-patient admission is linked to experiences of external factors, such as fear of violence, poor communication, lack of autonomy and inadequate ward routines. It is a priority that mental health services try to evaluate, monitor and improve such key experiences of inpatient admission. However, patient satisfaction is also linked to internal factors, such as conceptions and expectations. This suggests that if mental health services wish to accurately evaluate patient experience, such services need to be aware of the complex relationship between patient satisfaction and patient experience.

The following three recommendations may facilitate more accurate assessment of patient experience in people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. First, qualitative methodology could be used to identify patients’ areas of concern, and then these specific areas of concern could be monitored using quantitative patient satisfaction measures. An example of a survey developed that assesses concerns identified by patients regarding psychiatric community care is the Carers’ and Users’ Expectations of Services - User version (CUES-U; Reference Lelliott, Beevor and HogmanLelliott et al, 2001). Second, if patient satisfaction surveys are used, existing psychometrically robust surveys should be preferred (Reference RuggeriRuggeri, 1994), and interpretation of the results could be aided by qualitative interviews. Third, carefully designed patient satisfaction evaluations are only one limited method of integrating patient experience and should be a component of a wider approach that includes patient advocates, patient committees and lay representatives in management and user-led research.

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Mapperley Hospital Doctors Fund.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.