1. Building on sand

The work that would become known as the Pillar Testament, or bKa’-chems-ka-khol-ma,Footnote 1 is one of the most significant pieces of Tibetan historiography. Variously dated to the eleventh or the twelfth century by modern scholars (Sørensen Reference Sørensen1994; Davidson Reference Davidson2003), the work presents itself as the last words of the seventh-century emperor Khri Srong-btsan (alias Srong-btsan-sgam-po), allegedly recovered from hiding in the mid-eleventh century by the Buddhist missionary Atiśa. The work offers a thoroughly Buddhist take on the early days of the Tibetan empire (seventh to ninth centuries) by casting the period as a formative era in which divine Buddhist forces graced and civilized the country. It is a locus classicus for tales on the origins of the Tibetans, the population's special relationship with the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara, the endeavours of the seventh-century emperor Srong-btsan and his status as an emanation of that same deity, the construction of the most sacred Tibetan temple and various other narratives of great cultural import, including ones detailing imperial relations with China, the introduction of a script from India and the provenance of the Plateau's most sacred statues. The work would be “constantly and copiously quoted” (Sørensen Reference Sørensen1994: 11) throughout the centuries by a throng of widely received authors and can hence rightly be called a pillar of Tibetan historiography.

Yet despite its foundational status, we know pitifully little about the work's textual history and its various witnesses. Although different redactions of the Pillar Testament are known to be extant, no substantial attempt has ever been undertaken to work out the relations between the available versions. This casts a dark cloud over any usage of the source by historians, and spells trouble for any attempt to settle the relative chronology of early historiographies, which are known to have influenced one another. Scholars who have inspected the available witnesses of the Pillar Testament have voiced a slight preference for the most widely accessible and most legible text, M (Sørensen Reference Sørensen1994: 640; van der Kuijp Reference van der Kuijp, Cabezón and Jackson1996: 47; Decleer Reference Decleer1998: 86 and 89), an edited book based on two manuscripts (sMon-lam-rgya-mtsho 1989: 1). However, the stated preference for this edition went hand in hand with appeals to inspect the work's transmission history in greater detail (Sørensen Reference Sørensen1994: 16; van der Kuijp Reference van der Kuijp, Cabezón and Jackson1996: 48; see also Vostrikov Reference Vostrikov1994: 28–30; van der Kuijp Reference van der Kuijp2013a: 123–27 and Reference van der Kuijp, Ehrhard and Maurer2013b: 327–28). This article sets itself that arguably overdue task.

In the following pages, I introduce several new witnesses of the Pillar Testament and compare a substantial portion of the available textual evidence in order to improve our grasp of its witnesses’ content, relations and history. By identifying and analysing a wide variety of changes (interpolations, misinterpretations of earlier exemplars’ narratives, the absorption of verses known from other sources, increasing literary symmetry between neighbouring chapters, etc.), the relations between the available sources grow clearer. Although the scant few witnesses do not suffice to reconstruct a stemma of the complicated transmission of this old and oft-copied work, important layers of accretion can be identified.

The chapters and passages selected for comparison concern key historiographical episodes detailing the work's own recovery, the invitation of a Tang princess to marry the Tibetan emperor, the first appearance of Buddhist items in Tibet, the retrieval of cult items from India, the introduction of writing and the imperial genealogy. (A comparison of the chapter on the Tibetans’ origins will be taken up elsewhere.) The analysis of these passages reveals that the Pillar Testament has been subject to substantial change over space and time, and that a variety of manuscript witnesses, and one in particular, deserves prior consultation in the future whenever eleventh–thirteenth century dynamics are under discussion.

2. Witnesses of the Pillar Testament

All in all, I will draw on six full witnesses of the Pillar Testament, as well as on a single fragmentary witness. Two of these are new to scholarship, while a third has long remained inaccessible.

The heretofore unrecognized witnesses consist, first, of a reproduction of an integral manuscript witness from Mustang, Nepal (N), that was unwittingly published in 1981. Nestled inside a biography of Padmasambhava, it occupies a visually inconspicuous spot towards the very end of the second volume, where it went unnoticed even by its publishers (ff. 815.6–912.9). The second new witness, Ya, is fragmentary and found in a chapter of a manuscript titled rGyal-po'i-bka’-chems from Yangser Monastery in Dolpo, Nepal, a microfilm of which was produced by the Nepal German Manuscript Preservation Project (NGMPP) and is held at the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin. I consulted a digital reproduction of this film. Although a different work, three folios of its final chapter (ff. 153a–156b1), which discuss the work's recovery by Atiśa, were apparently drawn from a witness of the Pillar Testament.

In addition, I also looked at a copy of the St Petersburg manuscript (P) that was first described and discussed by Vostrikov in the 1930s (Vostrikov Reference Vostrikov1994: 28–32) yet has generally remained inaccessible to non-USSR and non-Russian scholarship. The original document, which is from Buryatia, is currently lost within the holdings of the IOM RAS in St Petersburg,Footnote 2 but was transliterated by Per Sørensen in the mid-1970s. A scan of the manuscript also exists.Footnote 3 I availed myself of the transliteration, kindly placed at my disposal by Per Sørensen, and a preview of the manuscript scans, which I was able to use to verify the quality of the transliteration. The original manuscript is written in a clearly legible dbu-med script.

Naturally, the long available witnesses are also taken into consideration. These include reproductions of two cursive manuscripts, published in Darjeeling in 1972 (D) and Leh in 1973 (L), and the aforementioned M, a modern edited and typeset book. Because the text of M does not appear to have been thoroughly proofread, carries no references to folio numbers and lacks an apparatus despite the claim that two witnesses were used, I also cite the nearly identical witness S. S is a transliteration of an dbu-can manuscript now held at the Bod-ljongs-rten-rdzas-bshams-mdzod-khang in Lhasa, with which it is cross-referenced.Footnote 4 This manuscript is likely to have been sMon-lam-rgya-mtsho's chief witness, who accessed it in Beijing in the late 1980s as the basis for M.Footnote 5 Although I had hoped to inspect this and his second manuscript (at Bla-brang) on a research trip to China, the fall-out of the Covid-19 pandemic barred me from doing so. There exists at least one other unpublished manuscript, a cursive witness with readings that deviate from all witnesses consulted in this article, which unfortunately also remains inaccessible.Footnote 6

To sum up, the following witnessesFootnote 7 are used:

1. D = reproduction of a cursive manuscript from sTog Palace (Ladakh), 14 chapters,Footnote 8 60 ff. (published in Darjeeling).

2. L = reproduction of a cursive manuscript from sTog Palace, 13 chapters, 96 ff. (published in Leh).

3. M = edited and typeset text in dbu-can script, based on two manuscripts, 16 chapters, 321 pp. (edited by sMon-lam-rgya-mtsho, published in Lanzhou).

4. N = reproduction of an dbu-can manuscript from Mustang, Nepal, 13 chapters, 49 ff. (published in Dalhousie).

5. P = transliteration of an dbu-med manuscript at the IOM RAS in St Petersburg, 13 chapters, 83 ff. (private collection of Per Sørensen).

6. S = typeset copy in dbu-can script of an dbu-can manuscript now held at the Bod-ljongs-rten-rdzas-bshams-mdzod-khang in Lhasa, 16 chapters, 266 pp. (published by the Ser-gtsug-nang-bstan-dpe-rnying-’tshol-bsdu-phyogs-sgrig-khang in Lhasa).

7. Ya = microfilm of an dbu-can manuscript of a rGyal-po'i-bka’-chems at Yangser Monastery, Dolpo, held at the Staatsbibliothek Berlin (NGMPP L1173/4), 35 chapters, with a passage from the Pillar Testament on ff. 153b4–156b1.

The heretofore unstudied N reflects the same redaction as L and helpfully fills a gap in that witness (N: ff. 910.5–12.3; cf. L: f. 795.2ff.). It also provides much-needed variant readings. Both are embedded in larger volumes with the Padmasambhava biography Padma-bka'i-thang-yig-ga'u-ma (see L: f. 803.4–7 and N: ff. 914.9–15.2).

Although P has previously been grouped with L as well (Sørensen Reference Sørensen1994: 639; Warner Reference Warner2010: 33, Reference Warner2011a: 5, n. 6), this classification is not quite correct. Though closely related, P has passages in which it deviates markedly from L/N, a chief example being the fourth chapter on the royal genealogy, where P presents a far more succinct and conservative narrative. Notable differences also appear in the chapter on Wencheng and most likely elsewhere, too.Footnote 9 Still, due to their close overlaps, the difficult readings in L, N and P can generally be navigated by consulting these three witnesses in conjunction (see Table 1).

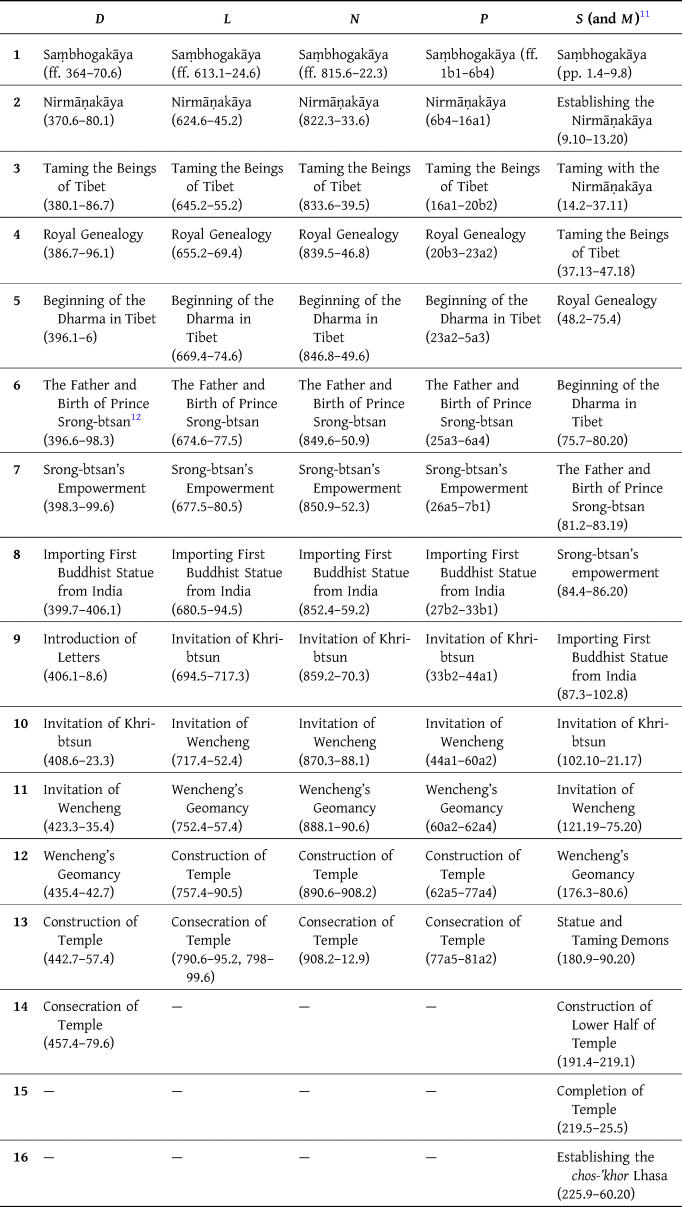

Table 1: Chapters of the chief witnessesFootnote 10

D, the briefest witness, is not only the hardest to read from a simple optical viewpoint but is also the most challenging from an orthographic and syntactic perspective. Unfortunately, this redaction does not seem to be extant in other witnesses, yet here too the identification of parallel episodes in other redactions can often assist in interpreting difficult or corrupted readings. The only integral witness to retain a hint of archaic spelling elements (it repeatedly retains ’a-rten [e.g. dpe’, bzhi’] and has a solitary myed), D will take on particular relevance in the discussion below.

3. Comparing the redactions

3.1. The work's recovery

The Pillar Testament is widely believed to have been retrieved from a pillar (e.g. Decleer Reference Decleer1998: 86 and 88; van der Kuijp Reference van der Kuijp, Cabezón and Jackson1996: 47–48; Sørensen Reference Sørensen1994: 15, n. 38; Yar-lung-chos-’byung A: 54 and B: f. 50.1). Yet a telling difference concerning the work's discovery exists between the most widely used edition and the alternative witnesses. D, L, N, P, as well as Ya, and other historical works, too (MTN K: 501.1–9, M: plate 363.2.2–6; see also ’Gos-Lo-tsā-ba's remark cited in van der Kuijp Reference van der Kuijp2013a: 126, n. 31), are unanimous in their understanding that the work was removed not from a pillar, but rather from a beam that extended from the column in question. This detail is instructive of the risk that scholars take in relying solely on S/M. In D we read:

[The crazy woman of Lhasa] said that in a crevice in a beam, [at a distance] measuring two-and-a-half fathoms due north from the top of the [temple's] vase-capped pillar, there was a document written by the lord who had constructed the temple (…) Then, the following morning, after the dge-bshes spyan-snga-ba rNal-’byor-paFootnote 13 had brought a tool for chopping wood with him, Atiśa measured the two-and-a-half fathoms on the beam, and cleft it. Thence, a single scroll appeared. (D: ff. 366.6–367.3)Footnote 14

The passage in P, L and N is substantially the same.Footnote 15 The parallel passage in witness Ya locates the original text inside a beam as well (f. 155a2–3),Footnote 16 as does the manuscript witness cited by Chab-spel-Tshe-brtan-phun-tshogs (1993: 38). Although the early biographies of Atiśa do not mention this beam, they do note that the work had been hidden in the vicinity of the column, not inside it (Eimer Reference Eimer1979: 285–86). Vostrikov (Reference Vostrikov1994: 28), relying on P, reported that the work had “been preserved (bkol) near one of the pillars (ka-ba) in the grand temple …” and accordingly translated the title bKa’-chems-ka-khol-ma as “The Will, hidden near the Pillar”. Eimer (Reference Eimer, Steinkellner and Tauscher1983: 45, n. 3) forwarded the same translation based on L. Based on the preponderance of textual evidence from witnesses of the work itself, something quite like this might indeed be the title's proper interpretation: “The Testament Set Aside [near a] Pillar”.Footnote 17

Naturally, the differences between the witnesses extend far beyond such details. More variation already pops up in the narrative surrounding the work's recovery. Immediately before Atiśa sets off for the temple where he will uncover the work, the reader first encounters him to the south-west of Lhasa, teaching demons at sNye-thang-’or, from where he looks towards what we should probably read as rKyang-thang and Ne-thang,Footnote 18 directly west of the city. There, as D has it, he spots a display of “various colours changing and transforming”.Footnote 19 The similarly phrased parallel line in the witness Ya instead speaks of fluctuating “light in the five colours”.Footnote 20 Both L/N and P detail that the vision was of meadows with differently coloured flowers bursting into bloom one after the other.Footnote 21 S/M, the most verbose of all witnesses, transforms these meadows or lights into yet another type of colourful display: a rainbow (S: 2.5–6, M: 2.8–9).

Such differences only grow. Upon inquiring of his audience as to the origins of this spectacle, Atiśa receives no answer in the fragmentary witness Ya and simply sets off to inspect the phenomenon himself.Footnote 22 In D, he receives a reply before travelling there: “In that area, there is a temple for the king's tutelary deity. [This temple] is the condition [at the base] of that [colourful display].”Footnote 23 The answer in L/N and P is almost identical to that of D.Footnote 24 S/M, in contrast, provides a stretched reverberation of the same reply:

The virtue [that gives rise to] this? To the east of the two mountains yonder, there sits the temple of the tutelary deity of the dharma king Srong-btsan the Wise, patrilineal descendant of the Lord gNya’-khri-btsan-po. [It is this temple that] is the virtue and the condition [at the base] of that [rainbow]. (S: 2.7–9, M: 2.10–13)Footnote 25

Yet more eye-catching is the same redaction's repeated inclusion of material that is wholly unparalleled in all other witnesses. For instance, the woman who tells Atiśa about the work's location is said to have been identified as a wisdom ḍākinī by the latter in D, P, L, N and Ya alike (D: f. 367.1–2, P: f. 3b5–6, L: f. 618.1–2, N: f. 818.4–5, Ya: f. 154b7). S/M, however, reports an additional claimFootnote 26 – that she was a rebirth of an imperial princess and a bodhisattva's emanation:

It is said that the crazy lady […] was a reincarnation of the Chinese [Wencheng] Gongzhu, and also that she was an emanation of the venerable Green Tārā. They are said to be non-dual, not separate, undifferentiated. (S: 4.3–5, M: 4.12–15)Footnote 27

Indeed, S/M carries numerous such claims of double identity in which protagonists are identified as an emanation or rebirth of one or the other renowned figure – claims that are often absent from the other witnesses. Atiśa himself, for instance, described as a respectable but subdued “mahāpaṇḍita named Pem-ka-ra-shri-snya-na” (i.e. Dīpaṃkaraśrījñāna) in D (f. 365.1),Footnote 28 is introduced as “his lord majesty, the great essence of the Noble Avalokiteśvara Mahākaruṇikā, the Indian paṇḍita named Dīpaṃkaraśrījñāna” in S/M (S: 1.19–2.2, M: 2.3–2.5).Footnote 29 As a likely extension of this identification with the bodhisattva, the missionary even becomes equated with the seventh-century emperor Srong-btsan in the redaction's appendix (S: 261.14–15, M: 315.15–16.1). Such impressions of changes effected in S/M are confirmed with more force and detail when we turn to other parts of the work.

3.2. The invitation of the Tang Princess Wencheng Gongzhu

3.2.1. The Chinese emperor's antagonism

We find striking evidence of the development of the Pillar Testament across its redactions in the famous narrative that details the invitation of a Tang princess to marry the Tibetan emperor Srong-btsan. This episode revolves around the clever minister ’Gar/mGar's visit to the Chinese court, where his legendary wit helps him navigate a series of challenges to win Wencheng Gongzhu's hand for his lord. Although this tale has been subject to substantial scholarly attention, its development in the witnesses of the Pillar Testament has gone unnoticed. A comparison provides ample evidence that S/M represents the most developed witness in a complicated cluster of narrative updates, while it appears to unveil D as the most archaic redaction, at least in this portion of the work. These developments are well illustrated by the role of the Chinese emperor, who changes from a relatively friendly figure in D, where he is merely strong-armed into a position unfavourable to the Tibetans, to an increasingly antagonistic figure in the other witnesses.

In D, the briefest of all extant redactions, the Chinese emperor is favourably predisposed towards the Tibetans. When the Tibetan mission arrives in China and requests the hand of Princess Wencheng, the emperor immediately assents to the proposal (f. 423.6–7). Even so, other members of the Chinese court voice their displeasure. A prince interjects that surely the Tibetans are sworn enemies, that they have murdered Chinese and usurped their lands and that, accordingly, the princess should preferably be sent to another, stronger Central Asian power, namely Ge-sar (f. 423.7–24.2). The empress, for her part, is affronted by the Tibetans’ poverty and would prefer to marry her daughter to the rich Persian king, while the princess herself favours Khrom on account of their good looks. Both dispatch messengers to their countries of preference (f. 424.2–3). Only when the Chinese emperor subsequently finds himself face-to-face with an international crowd of 400 men – 100 envoys from each of the four candidate countries – does he decide that the princess shall not be directly awarded to the Tibetans, but rather to the winner of a contest of acumen (f. 424.3–6).

After the Tibetans, guided by the crafty ’Gar, win this contest, “the Chinese ruler”, D continues, “was amazed at the Tibetans and awarded Gongzhu to the Tibetans”.Footnote 30 But the emissaries from the three other states object, and threaten to destroy China with armies, fire and water (f. 425.2–4). Intimidated, the emperor is forced into announcing a second trial. Although minister ’Gar again outsmarts his rival emissaries, he is denied the princess once more, as “the three [other parties] threatened like before [with] armies, fire, water, and so on” (f. 425.5).Footnote 31 This pattern repeats in a highly word-economic fashion for a total of six trials (f. 425.5–26.4), with only the seventh test definitively settling the matter in favour of the Tibetans (ff. 426.4–29.1). With the emperor's family resisting his decision and threats of war looming at every turn, there is little in the narrative of D to suggest that the Chinese emperor himself thought little of Tibet.

In contrast, in L/N (and P) the king treats the Tibetans with animosity from the outset. There, the notion that Tibet is an “enemy of China” that “robs all [Chinese] lands”, an objection voiced by the Chinese prince in D (f. 423.7–424.2, same in S: 133.3–6, M: 160.10–12, MKB: f. 236.4–5, rNam-thar-bka’-chems: cycle 2, f. 35a5–6), issues from the mouth of the emperor instead (L: f. 718.3–4, N: f. 870.7–9; also P: f. 44a6–44b1). From the start, he is adamant in his refusal of the Tibetan marriage proposal, preferring to send his daughter to the Indians – a party wholly absent from D. Indeed, with the king now also having a favourite contender, India, the narrative continues with 500 suitors, rather than 400 (L: f. 719.1, N: f. 871.2).Footnote 32

Although the king is again “amazed” at the Tibetans after the first trial and concludes that they are deserving of his daughter, the other foreign powers threaten him with violence and destruction (L: f. 719.7–720.2, N: f. 871.6–7) and thus precipitate a second trial. Yet in this redaction, the foreign powers need only threaten him once: each subsequent Tibetan victory is dryly followed by a note that the king announced yet another test, omitting any additional mention that his hand was being forced. In contrast, such repeated arm-twisting is still noted in the closely related P.Footnote 33

In S/M, the antipathy of the Chinese king towards the Tibetans is most pronounced. Here, all blame is loaded squarely onto the shoulders of the emperor himself. First, the mission is refused permission to see him for a full week. When minister mGar finally gets to present gifts and ask for Wencheng's hand, the ruler and his retinue simply laugh in his face (S: 123.6–124.5, M: 148.17–149.19). The Tibetan victories in the suitor trials, moreover, are never followed by foreign threats.Footnote 34 Upon completion of the first trial and mGar's rightful request for Wencheng, the emperor goes back on his word without external prompting, noting, “this [victory] does not suffice: the tasks have not yet been completed”, and simply refuses to hand over the princess (S: 135.5–7, M: 163.1–2).Footnote 35 The emperor announces a second trial instead, only to renege once more when the Tibetans again emerge victorious. He repeats this duplicity four more times (S: 135.7–38.17, M: 163.2–67.3). In S/M, then, the Tibetans’ quarrel is no longer with various side characters but rather with the Chinese sovereign and father of the bride-to-be, now the undisputed antagonist.

Such differences between the witnesses make it exceedingly unlikely that the shortest witness D was somehow summarized from a narrative like those in L/N, P or S/M. Instead, we see a pattern, perhaps reflecting a gradual development: the longer and wordier the witness, the more antagonistic the Chinese emperor. It is not altogether clear what prompted these changes: developing perceptions of Sino-Tibetan relations, a desire for increased literary parallelism with the previous chapter (describing a similar but initially testy visit to Nepal) or perhaps misinterpreted elaborations of what a particular witness's exemplar had only referred to tersely.Footnote 36 Regardless, it is the narrative as presented in S/M that aligns most neatly with famous instantiations of the tale that are typically considered to be of far later date, such as the one found in the fourteenth-century rGyal-rabs-gsal-ba'i-me-long (Sørensen Reference Sørensen1994: 215ff.).

3.2.2. Minister mGar's letters for the emperor

A famous sub-episode in the narrative on the invitation of Wencheng is also marked by a notable difference between the witnesses. In S/M, prior to the Tibetan mission even being allowed to participate in the trials, it faces a sustained, threefold critique that castigates Tibet as inferior to China and unworthy of receiving the princess. Minister mGar successively retorts by providing pre-written responses in boxes of precious metals, which had been entrusted to him by his lord back in Tibet. This trio of letters provides ample narrative opportunity to highlight the Tibetan emperor's divine status and superior standing, and indeed it does not fail to impress China's ruler (S: 124.5–132.15, M: 149.19–159.19), who tumbles from his throne in shocked response to the third letter (S: 132.9–11, M: 159.11–14).

Yet this entire passage, famous though it may be, is clearly an interpolation. Not only is it absent from D, P, L and N,Footnote 37 but its presence in S/M also garbles its narrative. While the emperor's fainting upon reading the last letter, for one, leads to his new-found conviction that he “must send” Wencheng to Tibet (S: 132.13–15, M: 159.17–19), the palimpsestic textFootnote 38 now leads into an older passage already familiar to the reader from other witnesses, in which he confers with his family on whom Wencheng should marry. The emperor, still physically impaired from reading the letters, first requires physical support from his ministers to return to the palace. Yet when he then broaches the burning topic with his family, he suddenly prefers India again (S: 132.18–20, M: 160.3–5). Considering the emperor's overwhelming recent change of heart, this clearly seems out of place. The unprompted about-face, however, makes sense when we postulate that here S/M, after the interpolation, again picks up the thread of a narrative as preserved in L/N, where the king had preferred India and never received any letters to change his mind.

Clarifying matters further, the source of the interpolated letters is nearby. The passage was certainly copied and expanded from the previous chapter, where a Tibetan diplomatic missionFootnote 39 travels to the Kathmandu valley – with three pre-written letters – to obtain Srong-btsan's first bride.Footnote 40 The repetition of the content of these Nepalese letters at the Chinese court involved manifest copying and created new consistency errors, too. In Kathmandu, to wit, the letters had served to assuage the misgivings of the Nepali king concerning the Tibetans’ lack of dharma, law and wealth. These issues were then addressed and fixed, and thus the Nepalese princess was procured. This marriage in turn resulted in the additional arrival of three important Buddhist statues in Tibet. In keeping with Tibet's concomitantly increased stature, in D, L/N and P, the Chinese emperor does not greet the Tibetan mission with the same qualms as his Nepali counterpart had done. He assents to their proposal in D, and in P and L/N it is past animosity, not inferior status, that initially precludes the marriage.

Only in S/M does the Chinese emperor repeat the now obsolete critiques that Tibet has no dharma, law or wealth (S: 124.5–29.17, M: 149.19–156.10). The Tibetan letters provided in response, too, simply repeat promises already made and fulfilled in the Nepali episode. Srong-btsan thus once more commits to erecting 108 temples, albeit with the added twist that their gates shall face towards China, not Nepal. He also again vows to institute law within a single day if granted his royal bride (S: 128.12–17 and 125.11–15, M: 155.2–7 and 151.11–15). The latter promise could sensibly be fulfilled only once. Although the repetition of these pledges in China creates a pleasant narrative symmetry with the Nepali episode, it somewhat hampers the plot's logical progression.

The textual development of the diplomatic letters on the topic of dharma can be reconstructed to a degree. Rather similar in form in D, L/N and P's chapters on the Nepali princess,Footnote 41 its place in the sequence of the three letters is transposed in P and S/M (P: ff. 37b2–38a4, S: 109.10–111.16, M: 132.11–135.3),Footnote 42 and it is substantially lengthened only in S/M. In the latter redaction, it was then copied into the subsequent chapter on the Chinese princess (as its continued transposition and a shared errorFootnote 43 still attest), where it again gained two new substantial interpolations. As such, the letter covers a modest 72 syllables in D's chapter on the mission to Nepal (f. 415.7–16.2), a more substantial 171 in the parallel passage in S (111.4–16) and explodes in size to 527 syllables in S's chapter on the Chinese princess (127.9–29.4).

This series of accretionsFootnote 44 lays bare the extent to which S/M has grown through editorial interventions. In S/M's chapter on the Nepali princess, the letter is first enriched with 1) claims of the Tibetan emperor's status as an emanation of Avalokiteśvara, 2) the elaboration of a promise to emanate 5,000 physical forms with still more emanations, and 3) a threat of war if Tibet's demands are not met. In the expanded letter for the Chinese emperor, the missive is additionally (and chiefly) supplemented by the magical birth of two forms of Tārā from the tears of Avalokiteśvara, who are then identified with the Nepali and Chinese princesses.

3.2.3. Obtaining the princess

The relatively muted nature of D's narrative is on fine display once more in (and after) the seventh and final suitor trial, during which the mission heads must pick out Wencheng from a long queue of women. In D, the line is made up of 100 ladies who stand in file at the market. Prior to this moment of truth, ’Gar had established a special rapport with the princess's chief servant and convinced her to provide tips on how to recognize the princess. After he successfully selects Wencheng from the line (ff. 426.5–28.2), the Chinese ministers realize that an informant (smra-mchu-ma) has been at play,Footnote 45 and perform a divination to find out what transpired. Yet thanks to clever measures mGar undertook before extracting the information from the attendant, the picture obtained through divination is distorted to the point of incredibility. This leads the prince to burn the divinatory trigrams in the mistaken belief that they are faulty (f. 428.2–7).

The longer narrative in L and N provides more material. One notable instance concerns the moment after mGar picks Wencheng out of the queue, here and in P also made up of 100 women (L: ff. 722.2, 723.2–3, 724.3, N: ff. 872.7, 873.2–3, 873.7, P: ff. 46b5, 47a6–47b1), a number that is notably boosted to 400 in S/M.Footnote 46 When the news spreads that minister mGar successfully selected the princess, “all Chinese” burst into tears, crying out that “the Tibetans have carried off our royal lady!”Footnote 47 After the divination, moreover, the ill-conceived command that the trigrams be burnt is shifted, again, from the prince to the emperor (L: f. 725.6–7, N: f. 874.5; but not in P: f. 47a.5–6). Further narrative padding is found in the subsequent elaborate exchange between mGar and the Chinese ministers (L: ff. 725.7–29.2, N: ff. 874.6–876.2; but not in P: f. 47a6).

Subsequently, all witnesses except for D insert a versified conversation between the princess and her father. When in D the Chinese emperor finally decides, once and for all, that Wencheng must indeed go to Tibet (ff. 428.7–429.1), she responds rather matter-of-factly:

Now, if I am to go to [live with] a barbarous king, [my father] must send the golden lha Śākyamuni as a gift, and father must send turnip seeds, treatises on handicraft and the eighteen types of craft, as well as great medical cures. (D: f. 429.1–2)Footnote 48

She also checks with minister mGar whether some specific natural resources are available in Tibet and, upon being told that they are, seems to have her doubts assuaged (f. 429.2–4). Although hardly enthusiastic, the Wencheng of witness D is not distraught at the thought of going to Tibet.

In contrast, in L/N, and indeed in all other witnesses too, Wencheng's address to her father is an emotionally charged passage, with the princess shedding tears while lamenting in versified form her terrible plight at having to move to Tibet. She complains about Tibet being cold and filled with terrible creatures, the snow mountains resembling the teeth of carnivores,Footnote 49 the land being a “desolate place of famine” where grain does not grow and the barbarian residents behave like demons.Footnote 50 These verses are wholly absent from D, appear in their most primitive form in P (ff. 47b3–48a5), grow in size in L/N (L: ff. 729.2–31.1, N: ff. 876.2–77.1) and are broken up and elongated by yet another line in S/M (S: 142.18–144.1, M: 171.17–173.6).

Clearly, then, the notion that the various witnesses of the Pillar Testament merely represent briefer or longer versions of a shared narrative along the same lines is mistaken. To pick out only one aspect, witness D presents an image of Sino-Tibetan relations that is far more amicable than that of the longer witnesses, whose texts include tears, hostility and depressed verse. Sino-Tibetan animus gains ground, with the Chinese emperor belittling and hoodwinking the Tibetan emissaries, the Chinese commoners showing dismay at their princess's betrothal and Wencheng herself describing the Tibetan populace as “foolish”, “impudent” and “unclean outcastes”.Footnote 51 The work's textual history came with substantial changes to both its narrative and tone.

3.3. The appearance of the dharma and the arrival of the first Buddhist statues

This impression of narratives that grow and develop across the witnesses is confirmed by other chapters, including the two that detail the first appearance of the Buddhist religion in Tibet and the importation of the first Buddhist statues. Although in these instances, the gist of the narratives is not as heavily affected as in the chapter on Princess Wencheng, we do again find that D is the most simplistic, and S/M by far the most elaborate.

In D, the chapter on the dharma's first appearance covers less than a single folio side. It simply records that emperor lHa-tho-tho-ri-snyan-shal, an emanation of Samantabhadra, relied on the Indian king Li-dza to introduce the dharma to Tibet (f. 396.1–3). It divulges no more on their relationship other than a reference to a different source. It goes on to note that four scriptures, each identified by name, appeared in Tibet on a beam of light and received the name gNyan-po-gsang-ba, the “Secret Fearsome”. The chapter swiftly concludes by noting that the veneration of these scriptures obtained good and blocked bad things (f. 396.3–5).Footnote 52

The chapters in L/N and P, which all cover some four folio sides and reflect the same redaction, dig deeper. The Indian king, who is here simply called DzaFootnote 53 and placed in Magadha, is revealed to be a descendant of Aśoka, the monarch fabled for his support of Buddhism. The king relates his ancestor's life story in a conversation with his subjects, who in turn suggest that their ruler visit the bodhi tree to pray that he may tread in Aśoka's footsteps (L: ff. 669.5–673.1, N: ff. 846.8–48.7, P: ff. 23a2–24b1). When he does so, Vajrasattva appears in the sky and “br[ings] down a rain of books” (P: f. 24b1–2).Footnote 54 The king venerates them, upon which a gust of wind lifts them up and out of view. Simultaneously, in Tibet, sunlight hits the emperor, from which a casket then appears that contains a volume with four scriptures: the gNyan-po-gsang-ba. The veneration of these incomprehensible writings bestowed blessings and granted the emperor the power of youth, allowing him to live for 120 years, to regrow lost teeth and turn silvery hair black again (L: f. 673.1–674.4, N: ff. 848.7–49.5, P: ff. 24b2–25a2).

S/M elaborates yet further on this template, coming close to doubling the length of the chapter as found in L/N and P. It starts with a book page of material unparalleled in the other witnesses before it arrives at the line with which the other three commence (S: 75.7–76.9, M: 90–91.10). Thereafter, too, additional material and twists appear. For one, the Tibetan emperor is here an emanation of Vajrapāṇi (S: 79.14–15, M: 95.7) and the interlocutor of the Indian king is not a nameless group of “subjects” (’bangs-rnams) (L: f. 672.6, N: f. 848.6, P: f. 24b1), but rather a venerable senior monk (gnas-brtan) (S: 79.2, M: 94.12–13). The description of how the first cult items made their way from India to Tibet is also quite different. Compare these lines from P and S/M:

Because [the king] made offerings [to the volume], a fierce wind arose, and the volume disappeared. (P: f. 24b3)Footnote 55

When [the king] elaborately made offerings to and consecrated [the items], ḍākas and ḍākinīs made a fierce wind of originating wisdom arise, and thus the volume and the stūpa were carried off into the sky and disappeared. (S: 79.10–13, M: 95.2–6)Footnote 56

In typical fashion, S/M features new agents and elevates the pious spectacle. An additional object, “a four-stepped crystal stūpa” (S: 79.8–9, M: 95.13–14), here accompanies the scriptures that flew in across the Himalayas. In a subsequent citation attributed to the emperor, this reliquary is again included among his cult items, while the citation itself, in another turn for the dramatic, changes from a generic quote (L: f. 674.3–4, N: f. 849.4–5, P: f. 25a2) to a death-bed instruction (S: 80.12–16, M: 96.7–10).Footnote 57

Similar impressions can be gleaned from the chapter on the first deliberate importation of Buddhist cult items, an episode set in the wake of emperor Srong-btsan's enthronement. Realizing that he needs a statue “for the sake of the beings of the Snowland” (D: f. 399.7),Footnote 58 the emperor is informed by heavenly creatures that a sandalwood statue of Eleven-faced Avalokiteśvara can be found on an island off the coast of southern India. To fulfil this task, a monk, who has an image of Amitābha on his head, subsequently emanates from a beam of light that issues from between the king's eyebrows. Following a detour in eastern India, the monk (re)converts a king in southern India who had fallen from his Buddhist faith, and enlists his assistance to retrieve the statue in question from a sandy isle (bye-ma'i-[g]le). After collecting additional items, including the tip of the bodhi tree in Magadha, the monk returns to Tibet to present the ten “objects of worship” (mchod-gnas) to the emperor.

The parallel chapter in L/N and P, which here reflect the same redaction, is substantially longer than in D. This difference is largely because the chunk that covers the introduction of writing (L: ff. 680.5–84.6, N: ff. 852.4–54.4, P: ff. 27b2–29a4) constitutes a separate chapter in D, an issue to which we shall return below. Regardless, the truly parallel content is still about 30 per cent longer (L: ff. 685.4–94.5, N: ff. 854.6–59.2, P: ff. 29b2–33b1). The southern Indian king, rather than merely being a sponsor of a non-Buddhist religion, is here said to have actively destroyed Buddhist temples, instituted a law based on the ten non-virtues and to have been seen slaughtering 70 goats in service of Śiva at an old Buddhist stūpa (P: f. 30b1–3, L: f. 687.4–7, N: f. 855.6–8). His co-operation with the monk's endeavour is framed as a method to redeem his grave sins (L: ff. 688.4–689.1, N: f. 856.2–4, P: ff. 30b6–31a3).

The statue's recovery is more elaborate, too (L: ff. 690.2–91.4 and N: ff. 856.9–57.5, P: ff. 31b3–32a3, versus D: f. 403.6–404.3), and a magically resounding instruction that leads to the statue's retrieval rings out not once (D: f. 404.1), but thrice (N: f. 857.4 and P: f. 32a1, cf. L: f. 691.1–2). L/N and P also note that the monk retrieved another type of sandalwood (gor-shi-sha ˂ Skt. gośīrṣa) near Mount Potala (L: f. 691.5–6, N: f. 857.6, P: f. 32a4). Although this material and its location are mentioned in D (f. 402.5–7), its retrieval is not. The story concerning the bodhi tree (D: f. 404.7–405.1) is also enriched, and now features two local princesses who are derided for their faith in the monk (L: ff. 692.4–93.1, N: f. 858.1–4, P: f. 32b2–5).

The differences are still more substantial in S/M. There, the light beam that directly produces the monk in other redactions first impregnates a girl, whose parentage and ancestry are provided as well, and who only gives physical birth to the monk months later (S: 91.6–14, M: 110.4–12). The heretical king is presented in yet more heinous detail: S/M explicitly adds that he engaged in murder, thieving and other sinful activities (S: 92.6–7, M: 111.6–8). Sacrificing goats but once in P, such slaughter is presented as a recurring event in L/N,Footnote 59 and even as a morning routine in S/M (S: 92.7–9, M: 111.8–11). The latter also describes the king's palace, a nine-storey building in the centre of town (S: 92.13–17, M: 111.15–18). The description of the eventually recovered statue is far longer, laying out in detail Avalokiteśvara's iconography (S: 98.2–13, M: 118.3–16), and the find of rare sandalwood near Mount Potala is more elaborate, too (S: 98.16–99.10, M: 118.18–119.16; cf. L: f. 691.5–6, etc.). Once again, S/M is notable for its drawn-out detail.

3.4. The introduction of the Tibetan script

The seventh-century introduction of writing is another milestone of Tibetan cultural memory for which the Pillar Testament constitutes a key source. Interestingly, redaction D is the only version of the work to place the introduction of letters (along with law) in a separate chapter, and to set this monumental episode after the arrival of the first Buddhist statues. This might, perhaps, reflect the older sequence.Footnote 60

Whatever the case, in all witnesses alike, the introduction of a script to the Tibetan court is chiefly occasioned by the need for diplomatic correspondence, even if the various narratives have different emphases. D first notes that the rulers of surrounding countries were amazed at hearing how Tibet was ruled in accordance with the dharma and that they consequently started sending annual gifts and tribute. These gifts bound for Tibet were accompanied by letters describing the presents. Yet, as D notes:

because there were only oral messages, but no writing, for sending return gifts from Tibet, sixteen children [of] Tibet's ministers were sent to India to study letters. But some ran into the three types of border demonsFootnote 61 and could not travel [on to India]. Some died because India was excessively hot. Some could not translate the Indian language because they were weak-tongued.

Subsequently, Thon-mi A-nu-ra-ga was provided with gold. He [had] a child, known as Thon-mi Sam-bo-ra-mi-chung, who was bright and prudent. [This child] was given a full bre of gold dust and sent to India to study letters. In southern India, he met with a brahman named Le-byin and offered [him] the gold, saying to him: “Please teach me letters”… (D: ff. 406.4–407.2)Footnote 62

In sum, the administration of international relations required writing and it was for such mundane reasons of diplomacy that Thon-mi was dispatched. Still, after he learnt letters, adapted the range of graphemes and gathered additional ones, “he was also taught Mahāyāna teachings in great number. When he subsequently returned to Tibet and offered [them] to the emperor, the emperor rejoiced greatly” (D: f. 407.7–408.1).Footnote 63 Religious scripture, in a word, was fortunate bycatch.

L/N and P agree to some extent by stating that Thon-mi's mission was occasioned by the lack of writing to accompany diplomatic return gifts. Yet these witnesses add that he was not merely “sent to India to study letters”, but rather “to study letters and dharma” (L: f. 681.4, N: f. 852.6–7, P: f. 27b5), ascribing a Buddhist motivation to what in D is a purely secularly inspired assignment. The scriptures he brought from India are specified as well. These endeavours made Thon-mi, L/N and P add, “the earliest among Tibet's translators and scribes” (L: f. 682.3–5, N: f. 853.2–3, P: f. 28a4–5). Upon his return, moreover, the emperor has him read the gNyan-po-gsang-ba inherited from his ancestor, whose four scriptures can now be identified and read for the first time (L: ff. 682.5–83.1, N: f. 853.3–5, P: f. 28a5–28b1; on the gNyan-po-gsang-ba and the introduction of writing more generally, see van Schaik Reference van Schaik, Kapstein, Imaeda and Takeuchi2011). This longer narrative lacks certain details present in D, such as the 16 children who failed to import literacy prior to Thon-mi, as well as Thon-mi's retrieval of letters from other centres of culture (D: f. 407.6, cf. N: f. 853.1, P: f. 28a.3 and the less preferable reading in L: f. 682.2).

S and M combine all these features, while also presenting other noteworthy differences. For one, the standing of Thon-mi is boosted. The figures who preceded him on trips to India are no longer 16 children, some of whose “tongues were too weak” to learn a foreign language. Rather, his predecessors were “many sharp-minded Tibetan men”, to whom only the suffocating Indian heat and dangerous demons posed insurmountable obstacles; none failed on account of their limited linguistic abilities. Thon-mi himself is no longer somebody's child, as is the case in all other witnesses, but rather “the brightest and wisest among the sixteen ministers” of the emperor. Accordingly, the mi-chung “small man” or “boy” that is part of his name in D, N, L and P is missing from most references in S/M (S: 87.9, 87.10, 88.20, M: 105.11, 105.12–13, 107.8), although it appears in a fourth mention (S: 89.1–2, M: 107.11) and once in the next chapter as well (S: 105.8–9, M: 127.13–14). S/M also includes L/N and P's line that Thon-mi was “the earliest among the translators and scribes of Tibet”, further adding that he is “said to be a speech emanation of Ārya Mañjuśrī” (S: 88.20–89.1, M: 107.9–10).Footnote 64 Another passage retained in D on the non-Indian provenance of some letters deviates and is more elaborate in S/M (S: 88.13–15, M: 107.1–3).

The Buddhist background of the alphabet's invention is also played up, even if dharma is not added to the official goals of Thon-mi's mission mentioned at the outset (a tiny flourish unique to L/N and P). S/M, however, provides specific Sanskrit words, such as dharma, as the reason why individual letters were added to the alphabet's inventory, even going so far as to claim that the letter ’a was included to distinguish short and long vowels (S: 88.4–8, M: 106.11–15), the latter of course being a phonemic feature of Sanskrit, not Tibetan. Such twists suggest to the reader that the Tibetan alphabet was conceived primarily to translate and transliterate Sanskrit, magnifying the Buddhist rationale behind its genesis.Footnote 65

3.5. The royal genealogy

The chapters on the royal genealogy open a window on yet another substantial development in second-millennium Tibetan historiography, which saw the Tibetan emperors evolve into distant kin of the Buddha. In this chapter, L/N and P deviate to such a degree that one must treat them as different redactions, while D (ff. 386.7–96.1) for the first time shows more elaboration than P does (ff. 20b3–23a2). S/M is once more the most elaborate, displaying abundant traces of editorial updates. Despite these differences, all witnesses retain some similarly structured content: 1) Avalokiteśvara looks out over Tibet and decides its inhabitants needs a fierce king, whom he shall emanate, 2) genealogical details on the first king among men, Mahāsammata (Mang-pos-bkur-ba),Footnote 66 and 3) the Indian origins of the Tibetan emperors, whose first incumbent was the son of the Indian royal dMag-brgya-ba.Footnote 67 The details of these central building blocks and the material between them, however, deviate substantially, and provide testimony on how the emperors’ ancestral identity was rewritten over time.

It is helpful to centre our discussion around P. After this redaction outlines the royal lineage of Mahāsammata, whose descendants include the Buddha and his son Rāhula with whom the royal lineage would finally die out, the text notes that “four sudden kings” ([g]lo-bur-gyi-rgyal-po, f. 21b4) appeared during the Buddha's life. These arise as if to fill the gap to be left by the impending demise of Mahāsammata's descent line. While the latter lineage ultimately hails from ābhāsvara deities (f. 21b2), these four new royals, thus P, are “said to be bodhisattva emanations” (f. 21b6).Footnote 68 This picks up the thread from the chapter's opening, where Avalokiteśvara contemplates that he must tame the unruly Tibetans by emanating a fierce king (ff. 20b3–5). L/N notes more explicitly that these four kings were “said to be emanations of the bodhisattva Avalokita”.Footnote 69

P traces the ancestry of the Tibetan emperors from one of these four emanated sudden kings, called ’Char-byed (P: f. 22a1ff.). ’Char-byed's great-grandson, born with bird-like features, was interpreted as an evil omen and therefore ordered to be murdered by his own father, King dMag-brgya-ba. Yet in a stroke of luck, the ministers charged with killing him dared not heed the command and placed him in a copper vat instead, which they tossed into the Ganges. The prince was found and raised by a farmer at the city of Yangs-pa-can (Vaiśālī). Eventually informed of his sorrowful past, he flees into the hills, reaching the Tibetan mountains. He meets with cowherds, who believe he arrived from the sky and crown him the first king of Tibet, naming him gNya’-khri-rtsan-po (P: f. 22a1–22b4). This account is largely in line with one of several versions of the royal genealogy presented in MTN,Footnote 70 which attributes this particular rendition to Emperor Srong-btsan himself. MTN therefore may well have drawn on a version of the Pillar Testament that was not unlike P (MTN K: 158.5ff., M: plate 114.1.1ff.).Footnote 71

Things look different in L/N, and decidedly foggier. After noting Avalokiteśvara's intent to “tame” Tibet and stating that the whole country came under the control of a “sudden king”, it addresses the origins of these new monarchs. The text curiously claims that their “lineage has continued unabated, being descended from the Indian lineage kings”, thus equating the sudden kings with Mahāsammata's line.Footnote 72 It goes on to describe Mahāsammata's origins and descendants. This includes a long narrative portion on Gotama, a renunciant from the lineage who ended up being unjustly executed. While dying impaled on a stake, he still magically managed to sprout two branches of offspring. The Buddha's Shākya clan (Skt. Śākya) hails from the branch called Bu-ram-shing-pa, and the Shākya itself in turn developed into three separate lineages (L: ff. 656.2–661.1, N: ff. 840.1–842.4).

This entire passage in L/N is a demonstrable interpolation. The material that appears before and after it is paralleled in P (f. 21a2–21a3, cf. L: ff. 656.1–2 and 661.1–2, N: ff. 840.1 and 842.4–5), while the text within it flies in the face of the surrounding content. To wit, P had noted that it would not elaborate on the subsequent reigns of some wheel-turning kings in Mahāsammata's lineage, and indeed does not (f. 21a1–2). L/N retains this note prior to the interpolation (L: f. 655.7–56.2, N: f. 839.8–40.1), yet goes on to discuss exactly that topic (L: f. 657.4–7, N: f. 840.7–9). Secondly, while the interpolation itself conflates the lineage and sudden kings, the passage following it again treats them as separate descent lines (L: f. 661.5–662.4, N: ff. 842.8–43.3). Clearly, the entire passage in L/N has been inserted at a later point, building on – and obfuscating – an earlier structure as retained in P.

After some subsequent shared content on the final generations of Mahāsammata's lineage and the first Tibetan king (P: ff. 21a2–22b4, L: ff. 661.1–65.1, N: ff. 842.4–44.6), L/N again inserts material. We find additional generational representatives absent from P, which creates a redundancy: the text now repeats how Tibet's first seven royal generational representatives dissolved into light upon death. L/N also adds subsequent royal history, including the fabled death of Gri-gum-btsan-po and the loss of his sky-chord, the ventures of his three sons and Ru-la-skyes, and the pedigree down to gNam-ri-srong-btsan (L: ff. 665.3–69.4, N: ff. 844.7–46.7), all topics absent from P. All in all, L/N's material comfortably doubles the length of P's chapter.

S/M absorbs these additional threads in L/N (while avoiding the documented inconsistencies), and proceeds to present several others, too. After its unparalleled opening material (S: 48.1–19, M: 58–59.9), a genealogy unfolds in which the Shākya clan takes on new prominence. The broader descent group of Śākyamuni Buddha is now not tentatively but firmly identified with the Tibetan imperial line, a claim that is at best inchoate and inconsistent in L/N and in blatant disagreement with P and D.Footnote 73 This claim is also accompanied by a slew of other assertions. The sheer number of identifications that S/M heaps upon the first king is another persuasive exhibit of the numerous changes that its text accrued over time.

While the other witnesses simply identify the first Tibetan king as a scion of a branch of Indian royals and imply that the Tibetan belief that he hailed from the sky was due to a misunderstanding, S/M seeks to identify him simultaneously as 1) being related to the “sudden kings” of India, 2) distant kin of the Buddha and a lineage king descended from ābhāsvara deities and Mahāsammata, 3) a denizen of a Buddhist heaven, 4) a Tibetan imperial ancestral sky god, and, possibly, 5) a figure from a later imperial generation, Bya-khri (S: 50.14–69.3, M: 61.6–82.16). In drawing together these discordant threads, S/M produces a narrative that, when compared to P, appears rather cluttered.

At the outset, the Tibetan emperor's Indian descent is enriched by equating the ancestry of the “lineage kings” with that of the “sudden kings” (S: 50.14–19, M: 61.6–11).Footnote 74 The Tibetan royal line is traced back to Mahāsammata, through the Shākya Ri-brag-pa, one of the three branches of the Buddha's clan (S: 63.20ff., M: 76.15ff.). When the exiled Indian prince runs off into the Himalayas, sky gods (gnam-gyi-lha) attach a sky-chord to his head and lift him up into the Buddhist heaven of Tuṣita, “atop the thirteenth tier of heaven” (S: 65.10–13, M: 78.11–13). There he gains the name srid-pa'i-mgon-btsun-phywa'i-lha (S: 65.14–16, M: 78.14–15), the heavenly ancestral gods known from imperial inscriptions.Footnote 75 In including these details, this redaction mixes Buddhist and non-Buddhist notions of the emperors’ celestial origins, stacking both on top of his Indian provenance as a lineage king, which already came with its own heavenly provenance. In this pastiche of different mythologies and pedigrees, the strand surrounding Avalokiteśvara fades into the deep background, if it is not lost altogether.Footnote 76

The notion that the emperors were distant kin of the Buddha spread both within this redaction (S: 109.12–16, 125.5–11, 262.8–15, M: 132.11–16, 151.5–10, 316.14–317.3) and outside of it, where it affected other important historiographies. A throng of historical works explicitly relies on the Pillar Testament for the claim that the Tibetan emperors were descendants of the Ri-brag-pa branch of the Shākya clan. These include well-known fourteenth-century works such as the rGyal-rabs-gsal-ba'i-me-long (Sørensen Reference Sørensen1994: 138), Hu-lan-deb-ther (33.3–9) and Yar-lung-chos-’byung (A: 40–41), as well as works from later centuries (e.g. mKhas-pa'i-dga’-ston, vol. 1: 159.7, Nyi-ma'i-rigs: f. 332.1–2). These changes in the genealogy had evidently already taken hold of an influential portion of the Pillar Testament's transmission no later than the fourteenth century. Evidently, however, less developed instantiations of the Pillar Testament claimed that the emperors hailed from an Indian royal branch that had appeared during the Buddha's lifetime, yet were in no way related to him.

4. Dating the witnesses

As has become evident from the discussions above, many redactions of the Pillar Testament surely postdate the inception of the work itself, whenever and in whatever shape it may initially have appeared. All witnesses, moreover, with the possible exceptions of D and P, contain a clear clue that demonstrates they cannot pre-date the thirteenth century. The most-used witness in the academic literature, as we shall see, may be far later still.

In D we read that the revered Jo-bo-Rin-po-che statue, a Buddha image reportedly housed in Lhasa's main temple since the days of Emperor Srong-btsan, once stood in Nālandā Monastery in contemporary Bihar, India, but had to be moved to a nearby monastery:

After that, [the statue] stayed at the sanctuary of Noble Śrī Nālandā. Then, after a Ru-ru army appeared, [the statue] stayed at the sanctuary of Odantapuri. After that, it was invited [and brought] as a reciprocating gift to the ruler of China in a sea ship, [being sent] along with a sūtra specialist, a mātṛkadhara, and a back-curtain. (D: f. 379.4–7)Footnote 77

If we compare this passage with its parallels in P and especially L/N, it seems that this narrative kernel on the statue's forced peregrination in India evoked in later audiences the Muslim raiding of Nālandā around 1200, even if the associated destruction is anachronistically set during the earlier Pāla dynasty:

[The previous Pāla ruler's] son [was] Dharmapāla. During his lifetime, a tīrthika army from Bhalendra,Footnote 78 in the west, was mobilized [to attack the Pāla territories]. All sanctuaries, including Śrī Nālandā's Temple of the Eight Protectors and the Temple of the Eight Tārās, were destroyed. All paṇḍitas were killed. All books were burnt. The dharma was suppressed … (P: f. 15a.2–4)Footnote 79

The mere appearance of a non-Buddhist army in D is, in P and L/N, presented as a full military onslaught in which lives, literature and religion were lost – evocative of the events around 1200. L/N explicitly conflates these attacks with the Muslim invasions of north-eastern India by subsequently noting that “the Tu-ru-ka [invaders] were tamed in accordance with the dharma”.Footnote 80

The ethnonym Tu-ru-ka (var. du-ru-ka) is an anachronistic reference to the armies headed by Bakhtiyar Khalji, who hailed from a Turkic populace in Helmand in present-day Afghanistan and led the conquest of the north-eastern Indian subcontinent at the turn of the thirteenth century. This ethnonym is intimately associated with the Muslim populations that start appearing in northern India at that time.Footnote 81 The combination of a tīrthika invasion of Magadha, the ravaging of Nālandā and north-eastern Indian Buddhism, and these events’ association with an alien, most likely Turkic, group from the west is too coincidental to have plausibly been written prior to the actual sacking of Nālandā.Footnote 82 L/N, I therefore submit, cannot pre-date the thirteenth century.

Although it is uncertain whether the ethnonym was once included in the redactions of P and D,Footnote 83 the term is certainly used in the parallel narratives of S/M (S: 29.17–18 and 30.6, M: 35.11 and 36.2) and Ya (ff. 45b.7, 46a.1, 46a.2), where Tu-ru-ka wreak similar havoc. Accordingly, these two texts should be dated after the twelfth century as well.Footnote 84 Further affirmation for such a terminus post quem for S/M is found in a mention of the gu-ru-mtshan-brgyad (S: 131.7, M: 158.6), a codified list of Padmasambhava's eight named appearances, which Hirshberg (Reference Hirshberg2018: 106) has suggested was coined in the thirteenth century, a time period that fits with the earliest available art-historical evidence.Footnote 85 Such cues and clues leave the narratives of D, and perhaps that of P, as the only extant witnesses of the Pillar Testament that could plausibly pre-date 1200.

For both D and P, furthermore, a terminus post quem can be found in their mention of Bya-yul-pa-gZhon-nu-’od (D: f. 367.5, P: f. 4a3), who lived from 1075 to 1138. This reference precludes a date for D's and P's full texts prior to the twelfth century. All other extant witnesses of the Pillar Testament, moreover, mention this figure, too.Footnote 86 All of these references are, however, part of the editorial content, and not the work's stories proper. It remains a distinct possibility that earlier versions of this work were around before 1100, but we certainly do not hold a copy from such an early period. It might even be the case that none of the extant redactions were finalized prior to the thirteenth century. Some of the available texts, moreover, may be far younger still.

Indeed, S/M, the most widely consulted redaction, might not even pre-date the fifteenth century – which would be hundreds of years later than even Davidson (Reference Davidson2003) suggested. This version contains content that is tied to, and may have been composed to retrospectively justify a contentious ritual act performed in the early fifteenth century. In 1409, the trailblazer of what would become the Buddhist dGe-lugs school, Tsong-kha-pa (1357–1419), crowned the revered Jo-bo Śākyamuni statue, causing uproar in various quarters (Blondeau Reference Blondeau, Krasser, Much, Steinkellner and Tauscher1997, Warner Reference Warner2011a). Crowned Buddhas, as Warner (Reference Warner2011a: 8) points out, were rather rare from a Tibetan art-historical perspective, and early descriptions of this particular icon universally fail to include any mention of it ever having worn a crown. Blondeau (Reference Blondeau, Krasser, Much, Steinkellner and Tauscher1997: 61), furthermore, has drawn attention to a prophecy apparently inserted into a (seemingly no longer extant) redaction of the Pillar Testament which predicted that Tsong-kha-pa would appear and “transform” the statue's appearance. This prophecy was clearly born of apologetics, and was actively cited by Tsong-kha-pa's defenders seeking to rationalize his controversial intervention in the statue's attire. Other apologists pointed out how the statue had once worn a crown in the distant past but had lost it after leaving Oḍḍiyāna, thus offering historical precedent for the statue's crowning in Tibet (Blondeau Reference Blondeau, Krasser, Much, Steinkellner and Tauscher1997: 66). This exact precedent also appears in S/M (S: 26.11–19, M: 31.15–32.4, translated in Warner Reference Warner2011a: 10). It is possible that, much like the aforementioned prophecy, this reference to the statue's crown (see also S: 22.18–19, M: 28.12–14) was also retroactively inserted so as to justify or explain Tsong-kha-pa's actions.Footnote 87 The other extant witnesses of the Pillar Testament, to be sure, make no mention of a lost headdress (D: ff. 378.1–380.1, L: ff. 638.2–45.2, N: ff. 829.8–833.6, P: ff. 13a2–16a1).

Still, we cannot preclude the possibility that within all the textual variation of the Pillar Testament documented above, some pre-fifteenth-century redaction (S/M or one of its forebears) did indeed describe the famous Buddha statue as having worn a crown, or even that exactly such a passage inspired Tsong-kha-pa to crown the statue to begin with. Some additional, admittedly circumstantial, evidence may, however, further strengthen S/M's connections to the incipient dGe-lugs. Its editorial matter, for one, may contain an allusion to the sMon-lam-chen-mo, the annual festival centred on Lhasa that was inaugurated by Tsong-kha-pa in, again, 1409 (S: 261.19–62.1, M: 316.5–7). It is also the only extant redaction that sees fit to deify Atiśa, the spiritual forebear of the dGe-lugs-pa (see section 3.1). Yet whatever the case, and regardless of this redaction's exact provenance and date – fifteenth century or not – it is obvious that S/M is notably younger than previously assumed and should not be mistaken for an archaic, let alone the most archaic, extant redaction.

5. The original Pillar Testament?

In this quicksand of textual variation, where do we turn for the original Pillar Testament? Was there ever such a thing? What do the witnesses reveal about a possible original of this influential historical work? All extant redactions certainly have something to say on the work's first exemplar. Although some of these references help us to understand details of the work's transmission history, others sow more confusion than they can dispel.

Strikingly, all redactions at one point or another disclaim originality and point beyond themselves for the origin of the textual tradition. The oft-cited redaction S/M, for its part, is frank in admitting that it is no Urtext. The editorial notes affixed to the work state that it is based on a collation of four manuscripts (S: 266.8–12, M: 321.9–13) that were marked by mistakes, omissions and elaborations, which had to be editorially settled. This pivotal note strangely seems to have escaped the attention of the scholarly record. This larger passage also formulaically claims that three redactions of various sizes – “expansive, medium and abbreviated” – were in circulation, and that its own text “has been arranged in line with the statement that this [redaction] is the most elaborate one”.Footnote 88 This implies that any interpolations in S/M's exemplars were more likely to be absorbed than rejected – far from a conservative text-critical approach.

Yet when we turn to the other witnesses in the hopes of finding the elusive original, we run into similar problems. The other extant redactions also all call upon another witness: they repeatedly invoke an external and more comprehensive Pillar Testament as source. Such references to a complete and bulkier witness, already noted in the 1930s for P (Vostrikov Reference Vostrikov1994: 29–31), most likely affirmed Sørensen (Reference Sørensen1994: 18, 640) in his view that the wordy S/M most closely reflects the original. Yet even S/M itself refers to such an external Testament (bka’-chems) for more information (S: 70.4, M: 84.1–2). All witnesses alike therefore explicitly signal that they are part of a larger textual tradition of which they themselves are not the root.Footnote 89 This is somewhat puzzling, because such references clash with other passages where these same texts do claim to be the emperor's testament.

This confusion as to whether the witnesses constitute primary or secondary textual evidence is most likely rooted in a historiographical tradition concerning the initial copying of the Pillar Testament. Early biographies of Atiśa, the work's purported revealer, claim that the textual material he retrieved was incomplete: his coterie only managed to copy part of the work (Eimer Reference Eimer1979: 286). ’Gos-Lo-tsā-ba, too, claimed that the extant copies were merely pale imitations of the original manuscript (see the citation in van der Kuijp Reference van der Kuijp2013a: 126, n. 31). All witnesses of the Pillar Testament itself also retain the notion that the original was hidden again after its retrieval. Witness Ya notes that “the chief manuscript” (dpe-’a-mo) was re-hidden inside a clay statue in the Glo-’bur chapel of the gTsug-lag-khang in Lhasa, in a line paralleled by all available integral witnesses of the Pillar Testament.Footnote 90 It is exactly such a “chief” (’a-mo) testament that some witnesses refer to as an external source for further reference (e.g. L: ff. 625.3, 656.2, 662.1–2 and 802.6–803.1). S/M's editorial notes attribute this passage on the whereabouts of the original document to one specific exemplar, which reportedly added that “this [autograph of the] Pillar Testament was copied into a small(!) booklet by dge-bshes rNal-’byor-ba”,Footnote 91 in a likely echo of the loss of textual material reported by Atiśa's biographies.

When witnesses such as L/N therefore style themselves an “abbreviated [version] of the scroll of the King's Testament”,Footnote 92 or D labels itself a “mid-sized religious history drawn from the King's Testament”,Footnote 93 they probably do so in a nod to this legendary original manuscript. This is also the case when D suggests that more information “is included in the scroll [of] the Testamentary Document” (D: f. 466.2–3).Footnote 94 Such references to the fabled original, reportedly indeed a scroll luxuriously executed in precious inks on paper set in silk,Footnote 95 rippled through the transmission history of the Pillar Testament. In the end, these allusions are likely to signify little more than that the circulating manuscripts never claimed exact identity with the mythical document crafted by the emperor's own hand.

Simultaneously, such references to a more expansive version of the work provided fertile soil for the textual tradition to grow. This is particularly evident in the passage of the royal genealogy in L/N, discussed above (in section 3.5), which inserted contradictory information where its exemplar had simply referred the reader to a more extensive witness, the “chief testament” (bka’-thems-’a-mo). Historically, editors’ belief in the existence of an original and larger work may have strongly influenced their editorial strategy when faced with different witnesses, nudging them to embrace some unparalleled passage as an exciting recovery of lost material, rather than to dismiss it as an interpolation. Such a belief would certainly appear to have informed the approach laid out in S/M's editorial matter discussed above. The study of such changes across the witnesses hence provides a road map that offers a bearing on the development of individual witnesses in relation to one another, and this brings our search for the fabled original squarely back to the witnesses’ varying contents.

Judging from my readings, which should ideally be complemented in the future based on other parts of the work, D generally retains the most basal text of all available witnesses. P's narrative is next, with the closely related L/N following on its heels. L and N clearly share a very close common ancestor, which in turn appears to be descended from the same forebear as P. Yet P appears to be the more conservative reflection of this common ancestor, as it lacks several innovations (and editorial imperfections) evident in L/N. S/M, finally, is clearly the most developed, and its readings, colophon and sheer length combine to demonstrate that it is a sustained contamination of multiple versions.

Regrettably, there is much missing evidence between the extant witnesses of the Pillar Testament, and the text-historical situation does not easily lend itself to exhaustive stemmatic analysis. This popular work was already subject to substantial textual divergence many centuries ago. Its textual tradition may accordingly have been open, i.e. subject to horizontal transmission between witnesses, long before S/M was ever created. The work's contents, moreover, repeatedly spilled out into the transmission streams of other works, and vice versa. Not only was it absorbed wholesale into a Padmasambhava biography (L/N), but it was also listed for inclusion in the collection Ma-ṇi-bka’-’bum (MKB: f. 11.2). One of its passages was excerpted into another treasure text (Ya), and there are repeated literal overlaps between the Pillar Testament and sources such as MKB and MTN,Footnote 96 whose transmission histories in turn are marred by questions of their own. To recover a reliable textual history from this poorly attested tumult poses a herculean task.

At this point, then, suffice it to stress that the apparently most archaic D is neither an Urtext nor a feasible complete archetype for the other extant redactions. An apparent bowdlerization in the chapter on the Tibetans’ origins, for one, sets it apart from the other redactions.Footnote 97 Its chapter on the royal genealogy was tampered with.Footnote 98 Its chapter on the temple's consecration is longer than the parallel chapters in L/N and P, and may contain innovations absent from these other witnesses.

Yet still, taken as a whole, D is the closest thing we presently have to a baseline of early versions of the Pillar Testament. Across the majority of passages studied above, the other witnesses are, in comparison to D, marked by narrative expansion, mythologization and the insertion of versified passages – elaborations that are often mirrored in sources such as MKB and MTN. Wherever early second-millennium historiography and the early Pillar Testament are at play, then, scholars would in the future be well advised to turn to D first, and to consult P, L/N and S/M after it.

The documented raft of changes this pivotal historiography underwent should, in the final analysis, alert us to the pitfalls hiding in the pages of sources whose textual history goes unexamined. The Pillar Testament circulated solely in manuscript form for the greater part of a millennium across a vast region, eventually bridging a 3,000-km expanse from Ladakh to Buryatia. Along the way, its stories shape-shifted, with figures and twists being added, amicable emperors becoming foes, ministers turning into bodhisattvas and the Tibetan rulers morphing into kin of the Buddha. The various witnesses of the Pillar Testament thus testify to shifts in how the founding history of Tibetan culture was remembered and passed on. Understanding this mutability is not only pivotal to our knowledge of the region's history, culture and religion, but also provides a better baseline from which to gauge the relations between this work and other early historiographies.

Acknowledgements

The research for this article was funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF (P34212). I thank Per Sørensen and Ulrike Roesler for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article, Tsering Drongshar for his help in transliterating portions of one witness and Michele Greenbank for her careful copy-editing. Finally, I gratefully acknowledge the particularly meticulous comments by an anonymous reviewer of this journal, which helped refine and draw out a number of relevant points.