Lockdown measures necessary to contain the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated social isolation are known to have impacted people’s mental health. An increase in mood disorders was detected, but this appeared to predominantly affect younger populations (Daly et al., Reference Daly, Sutin and Robinson2021). We therefore investigated the severity and nature of depressive symptoms among older adults referred to specialist mental health services in south London during the first lockdown (March to July 2020) compared to a pre-COVID comparison period (February to July 2019).

Data were analyzed from the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM) Clinical Record Interactive Search (CRIS) platform, providing access to over 500,000 de-identified health records from SLaM, one of Europe’s largest mental health care providers (Greig et al., Reference Greig, Perera, Tsamakis, Stewart, Velayudhan and Mueller2021; Mueller et al., Reference Mueller, Perera, Broadbent, Stewart and Velayudhan2022). We ascertained all referrals to community and general hospital liaison mental health services for older adults for the following time periods: the first UK COVID lockdown (16/3/2020–5/7/2020, 16 weeks) and the equivalent period in the preceding year (18/03/2019–7/7/2019, 16 weeks).

Depression severity was measured using the “Problems with depressive symptoms” subscale of the Health of The Outcome Scales (HoNOS). For this analysis depression scores were classified into “no or minor problem,” “mild problem” and “moderate-to-severe problem.” From available CRIS natural language processing applications, extracting clinical information from text fields in the electronic health record, we ascertained recorded depressive symptoms within a period from 6 months before to 6 months after referral date. These were grouped into three categories: (i) negative cognitions (guilt feelings, helplessness, hopelessness), (ii) affective symptoms (anhedonia, apathy, poor motivation, tearfulness), and (iii) somatic symptoms (agitation, reduced appetite, impaired concentration, disturbed sleep, lack of energy). We compared patients referred during lockdown with those referred in the previous year and determined the odds of an association between the presence of lockdown and clinical characteristics, including depression severity and depressive symptoms, applying logistic regression models. In these models, the respective clinical characteristic was the dependent variable and the presence of lockdown the independent variable. The p-values generated in the 17 analyses were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate procedure.

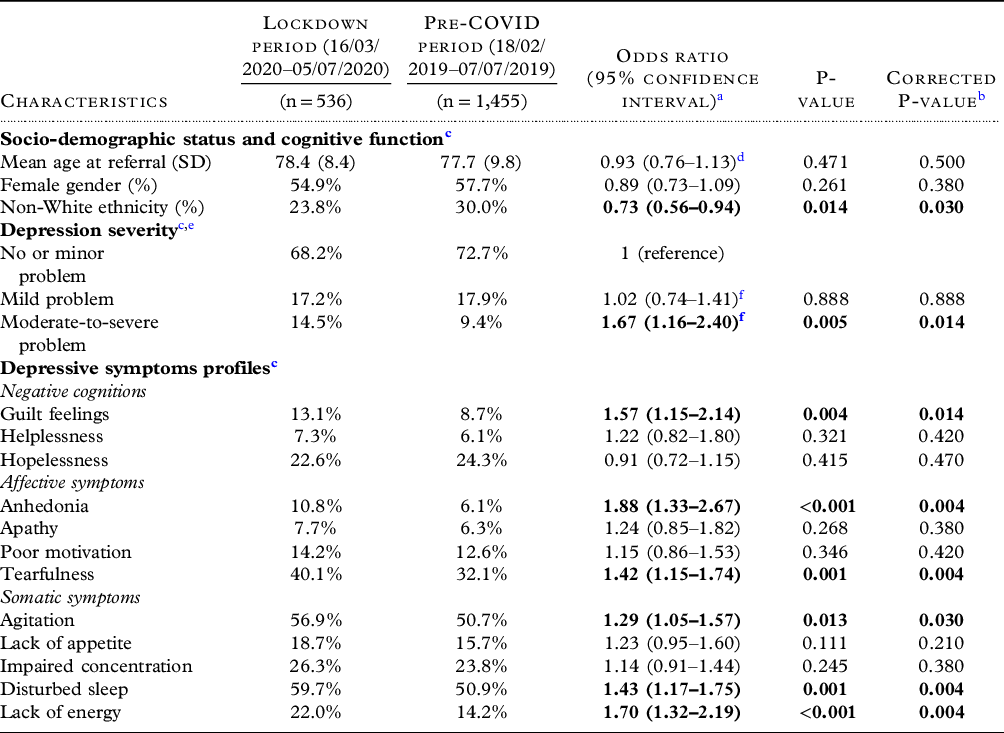

Across the two observation periods 1,991 referrals were accepted by mental health services for older adults, only 26.9% of which occurred during the lockdown period. Characteristics of patients referred during lockdown and the pre-COVID period as well as logistic regression models are presented in Table 1. During lockdown, proportionally fewer patients from ethnic minority groups were referred (odds ratio (OR): 0.73) and more frequently patients with moderate-to-severe depression (OR: 1.67), guilt feelings (OR: 1.57), anhedonia (OR: 1.88), tearfulness (OR: 1.42), agitation (OR: 1.29), disturbed sleep (OR: 1.43), and lack of energy (OR: 1.70).

Table 1. Characteristics of referrals during lockdown and the period pre-COVID and logistic regression models examining the association of the presence of a lockdown and clinical features

Significance of bold values indicates p<0.05.

a Unadjusted logistic regression models with patient characteristics as dependent and the presence of lockdown as independent variable.

b Corrected using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate procedure (for 17 comparisons).

c At/around the time of referral.

d Odds ratio for being older than the mean age of the cohort.

e Depression severity according to Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS).

f Compared to no or minor depression as reference group.

While there was only a small proportional increase in referrals with more severe depression, a substantial increase in certain depressive symptoms was detected during lockdown. Depressive symptoms more prevalent during lockdown were related to inactivity (anhedonia and lack of energy), but also higher levels of distress (tearfulness, agitation, guilt feelings, and disturbed sleep). While inactivity might be a consequence of loneliness and social isolation (Greig et al., Reference Greig, Perera, Tsamakis, Stewart, Velayudhan and Mueller2021), the higher levels of distress are potentially caused by exacerbation of existing mental health problems and fear of life-threatening consequences of COVID-19 (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2020). External factors such as illness or death of friends, loss of social roles, and relocation have been shown to have a negative impact on late-life mental health by reducing social networks, and older adults with lower levels of social contact and/or lower tolerance of uncertainty are more likely to be depressed during a pandemic and lockdown (Glowacz and Schmits, Reference Glowacz and Schmits2020). While our study’s main strengths include a large sample size from a routine clinical setting, it would be useful to compare this with subsequent lockdowns to determine whether there were any differences with fluctuating social restrictions and also to estimate the longer-term impact of the prolonged pandemic on late-life mental health.

In conclusion, in this observational study depressive symptoms in patients referred to older people’s mental health services appeared to be qualitatively different during the first COVID-19 lockdown. Clinicians need to be aware of such potential effects and tailor assessment and management accordingly.

Conflict of interest

RS has received recent research support in the last 36 months from Janssen, GSK, and Takeda. GP, CM, WYC, and LV declare no conflicts of interest.

Source of funding

The data resource, GP, CM and RS are part-funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London, and RS by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration South London (NIHR ARC South London) at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, and by the DATAMIND HDR UK Mental Health Data Hub (MRC grant MR/W014386). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Description of authors’ roles

The study was conceived by LV and WYC. Analyses were carried out by GP and CM. The manuscript was written by LV and WYC and finalized by CM with substantial text contribution from all authors.