The Contested Nature of the Hungarian Minority Policy

Despite Hungary’s relatively homogeneous ethnic composition, the main features of its policy toward internal minority groups have been the focus of recurrent debates within politics and academia since the fall of the Communist regime. These features include the relevant provisions of the 1949 constitution amended during 1989–1990; the more recent 2011 constitution (Fundamental Law); the 1993 and 2011 minority laws and their implementation; and the complex system of minority self-governments, the national variant of national cultural or nonterritorial autonomy (NTA),Footnote 1 which forms the core of this minority legislation. The result of political compromises, these laws often had too general and declarative provisions allowing for different interpretations and lacking concrete procedures for implementation. First and foremost, however, they have given rise to contestation regarding the basis of Hungary’s political community and how civic and ethnic concepts of nationhood and citizenship might be accommodated within it. Relevant considerations here are the presence of sizeable ethnic Hungarian minorities living in the neighboring countries and the fact that Hungary’s internal minorities are relatively small in number and territorially dispersed in terms of settlement, they feel firmly attached to the state and its dominant culture, they are at an advanced stage of linguistic-cultural assimilation (Bartha and Borbély Reference Bartha and Borbély2006),Footnote 2 and they have not been politically mobilized along ethnic lines. With the exception of the Roma, they are also well integrated in socio-economic terms. As such, another contentious issue has been whether the objectives of the minority law and minority self-governments with their emphasis on preserving minority languages and cultures reflect the basic needs and interests of the predominantly Hungarian-speaking, yet socially and economically marginalised, Roma (Vizi Reference Vizi and Rechel2009, 128).

The wide-ranging literature on the topic suggests an uneven and even contradictory picture regarding the main features and objectives of Hungary’s policy toward its domestic minorities, especially when it comes to assessing the interplay between external and internal policies. Signalling Hungary’s commitment to adopting and further developing international standards of minority rights and its intention to join Euro-Atlantic institutions (Galbreath and McEvoy Reference Galbreath and McEvoy2012, 278), the 1989 constitution and subsequent 1993 minority lawFootnote 3 granted extended and collective minority rights in the form of nonterritorial autonomy. In this way, the country was placed among the leading nations in the field of European minority protection (Pan and Pfeil Reference Pan and Pfeil2002), a fact which has led some political actors to portray the Hungarian model as exemplary and inspirational at the European level.Footnote 4 As a consequence, however, a growing number of scholars have argued that Hungary’s minority policy is motivated not by a commitment to “Europeanization” per se, but rather by a desire to set an example abroad and put pressure on neighboring countries (see, for example, Deets Reference Deets2002, 40; Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka2007, 392; Tesser Reference Tesser2003, 506). In this respect, the issue of domestic minorities is consistently portrayed as a secondary and very much subordinate factor. Yet, if one accepts that the minority law was intended solely to provide Hungary with credible and effective leverage in its external relations, the obvious question arises as to why the law in practice provides such limited space for minorities within what is essentially a Hungarian-dominated nation-state, why minority demands could only be partially met, and why the 1993 law only vaguely resembled the earlier draft proposal of the minority organizations.

From a different perspective, the more relevant question is whether a law like the Hungarian one would have had a major impact if adopted in Romania, Slovakia, or Serbia in the middle of the 1990s for larger, territorially concentrated, more conscious, and politically mobilized Hungarian communities. Overall, it seems very doubtful whether these expectations, such as those to improve the situation of Hungarian communities abroad by creating and maintaining a progressive system of minority protection at the domestic level, especially if regarded not only on a rhetorical level but also in practice, were ever well-founded. In so far as the major aim was to achieve a certain combination of territorial and nonterritorial autonomies for the Hungarian communities abroad, the only neighboring state that was demonstrably influenced positively by the Hungarian model was Croatia, where the 2002 constitutional law on the rights of national minorities has created national minority councils for the country’s mostly small and scattered minorities, including the Hungarian one (Petričušić Reference Petričušić, Malloy, Osipov and Balázs2015, 55).

As we argue below, those who see the 1993 minority law as motivated by external concerns cite the preceding parliamentary debates of 1992–1993 as evidence for this claim, but without fully analyzing these debates. At the same time, they neglect the less-than-inclusive nature of Hungary’s post-communist state- and nation-building projects with regard to minority claims, a feature which, as in the region more broadly, stemmed from the country’s recent past. Consequently, public institutions and policies have come to be predominantly understood as the almost exclusive property of the titular nations, and minorities have been excluded (Agarin and Cordell Reference Agarin and Cordell2016). The close examination that we provide in this article leads to a more nuanced assessment, which reconciles the seemingly different findings of previous studies and brings to light these other, often neglected, factors, such as the Communist legacy, the role of internal minorities and the desire to compensate the previously nonrecognized and discriminated Roma population. All of these factors, we argue, contributed to putting the minority law onto the political agenda and led to the compromises shaping its eventual character. Overall, we argue that while the setting of the early 1990s saw both a transfer of Western standards of minority rights and a revival of NTA as a largely Central European contribution to the management of ethno-cultural diversity (Smith and Hiden Reference Smith and Hiden2012), their implementation has been seriously distorted due to the continuing influence of communist legacies. Thus, despite a strong commitment to minority protection motivated largely by concern for Hungarian minorities abroad, Hungary was no different from other post-communist countries, and remains paradoxically embedded in the broader context of post-communist state- and nation-building processes in which most countries in the region have focused primarily on securing the institutional positions of the majority language and culture (Csergő and Regelmann Reference Csergő and Regelmann2017, 215–216; Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka, May, Modood and Squires2004).

In order to address the questions above, the first section of our study provides a brief analysis of the historical background, with particular regard to its impact on post-communist policy making. The second part takes the analysis further by investigating the parliamentary debates on the 1993 minority lawFootnote 5 and presenting the main findings gathered from 18 in-depth interviews conducted in 2015 and 2016 with former and current politicians and minority leaders involved in minority issues or in the creation of the minority law.

In the Shadow of Trianon: Historical Legacies of Minority Policy

Prior to the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the 1920 Treaty of Trianon, Hungary was a multi-ethnic state in which Hungarians comprised only about half of the total population. An initial minority law of July 1849 was never implemented due to the suppression of the 1848–1849 Revolution. The subsequent 1868 Act on Nationalities was less generous by comparison (Kővágó Reference Kővágó1981), since it recognized only the Hungarian civic nation and thus largely neglected the special and collective interests of the national minorities (Hajdú Reference Hajdú and Pál2005). Although the country lost most of its former territories and millions of citizens with non-Hungarian origin in 1920, the now almost-homogenous Hungary—in common with other successor states to the Austro-Hungarian Empire—continued to pursue a generally oppressive line against its minority nationalities (Romsics Reference Romsics2004). As the then-largest minority, however, Hungary’s Germans benefitted from a relatively extensive framework of opportunities and minority rights, including monolingual minority schools, probably because the state remained mindful of the growing influence of Germany in East Central Europe in the interwar years (Tóth Reference Tóth and Tóth2005, 175).

Following the country’s defeat in World War II and the onset of a communist ideology proclaiming proletarian internationalism, minority issues were not high on the agenda. Vizi (Reference Vizi and Rechel2009) refers to them as a “political taboo.” In the Stalinist era, Soviet interests and directions determined the management of minority issues. According to Fehér (Reference Fehér1993, 139), the first phase of communist minority politics was shaped by a theory and practice of “automatism” connoting “not … explicit antinationalistic politics but … a special type of Hungarian nationalism based on the neglectful attitude which says ‘let [minorities] go by themselves, they are going to disappear anyway.”’ Balogh (Reference Balogh, Feitl and Sipos2005) argues that the provisions of the 1949 Constitution declaring equal rights for all Hungarian citizens and guaranteed possibilities for minority language education and culture were only realized partially. Moreover, the 1949 constitution did not address “the question of parliamentary and local council representation of the nationalities” (Balogh Reference Balogh, Feitl and Sipos2005, 136), while the later amendments to it during 1989–1990 contained only vague and too-general wording in this area.

The period immediately after World War II was also marked by deportations, exchange of populations, and discrimination against those belonging to national minorities (Fehér Reference Fehér1993; Tilkovszky Reference Tilkovszky1998). This brought a significant decrease in the minority population and caused fear among those who remained in Hungary. In these circumstances, the communist regime was concerned only with keeping up a pretense of relatively good practice toward national minorities, the expectation being—according to the precepts of automatism—that they would be assimilated within a few decades anyway (Tilkovszky Reference Tilkovszky1998). The political rhetoric of the day often referred to Hungary as an almost homogeneous country in terms of its national composition. From the perspective of a member of a national minority, this sounded offensive. As Fehér argues (Reference Fehér1993, 5): “Some people claim that basically Hungary is a national state. This is an antinationalist statement because it declares that the nationalities are inessential. If a country is basically a national state, then its national minorities are not important.” During communism, this view could be used to justify the government’s neglect of the country’s national minorities and, by default, support their assimilation. Leaving the dominant Hungarian majority in a state of ignorance concerning national minorities also affected the dominant societal perception in this area. In subsequent decades, those holding positions of power often have had relatively low levels of awareness of national minorities and the continued issues they face.Footnote 6

Following the communist takeover in 1948, associations of nationalities came under the control of the communist party: the local branches of the Democratic Alliance of Southern Slavs of Hungary and the Democratic Alliance of Slovaks of Hungary were shut down. The Cultural Alliance of the Romanians of HungaryFootnote 7 was founded in 1948 and the Cultural Alliance of German Workers of Hungary was created only in 1955 (Tóth Reference Tóth and Tóth2005). These national minority organizations represented the interests of the government toward the minority nationalities rather than the other way around (Fehér Reference Fehér1993). In the early 1960s the government closed schools teaching predominantly in minority languages inherited from the interwar period, replacing them with bilingual schools (Fehér Reference Fehér1993). A regulation in 1963 even banned “non-Hungarian sounding” first names from registration, though this was later repealed in 1968 (Tilkovszky Reference Tilkovszky1998). That same year (1968) marked the start of a gradual change in Hungarian political rhetoric that brought nationality issues back onto the agenda and sent the message to the Hungarian public and to Hungarians living as minorities outside Hungary that “we did not forget about your cause, we are trying our best even if this is not reciprocated from the other side” (Földes Reference Földes2007, 114). However, while this marked a discernible shift, it did not immediately translate into real action (Földes Reference Földes2007). For instance, in 1972, an amendment to the Constitution saw inclusion of a reference to the right of minority nationalities to use their native tongue in educationFootnote 8; this was not implemented in practice, however, since the existing minority schools did not fulfil the necessary requirements: they lacked trained teachers proficient in the relevant languages, as well as appropriate methodologies and curricula (Tilkovszky Reference Tilkovszky1998).

The amendment of the constitution nevertheless marked the end of the period of automatism and the arrival of a new era and policy line. This was partly occasioned by a changing international context in which the United Nations (UN) had become more concerned with the issue of protecting national minorities. Against this background, a delegation from Hungary attended a UN conference in 1974 in Yugoslavia and expressed its willingness to cooperate with the new UN line on minority issues (Tilkovszky Reference Tilkovszky1998). The policy shift also reflected the broader divisions then emerging within the Soviet bloc and Comecon, as well as generational changes in party leadership that saw the communist countries take diverging paths. In Hungary, a significant and influential part of the cultural elite raised concerns over Hungarians living in neighboring countries and their worsening circumstances.

It was at this stage that the government started to discuss topics such as the “bridging role of national minorities,” the need to support minority languages and cultures, and the ethnic policies of Engels and Lenin. This led to the creation of a new strategy for national minority politics (Tilkovszky Reference Tilkovszky1998), based on the rationale that Hungary could claim little in the way of minority rights from neighboring countries if it could not also provide its own domestic examples of good practice (Dobos Reference Dobos2011). On August 1, 1975, Hungary also signed the closing document issued by the Helsinki Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, which committed states to respect the human and minority rights of their populations (Balogh Reference Balogh, Feitl and Sipos2005). Tilkovszky (Reference Tilkovszky1998), however, argues that by this time, the assimilation of Hungary’s minority nationalities had already reached such an advanced level that it could not weigh equally in any dispute with the neighboring countries over national minority issues. The suspicion thus remained that the measures taken by the communist government simply amounted to a façade, rather than being driven by a genuine desire to provide real support to the nationalities in Hungary. Aladár Horváth, a former Member of Parliament (MP) and current President of the Roma Parliament, remembers this period as follows:

[During communism] the rhetoric [communication] was different than the reality. They told us that they wanted to ensure minority rights in Hungary for the national minorities according to international agreements, but their real aim was to support Hungarians living in neighboring countries. On the one hand [minority representatives] were also there at these meetings and on the other hand [the government] wanted to send a message to the power of the neighboring countries that this is how we expect you to treat the Hungarians living in your countries.

(Interview HUN-2.1.1, with Aladár Horváth, September 10, 2015, Budapest)Given the overall nature of the political system, these changes were not translated into any kind of political representation of minority interests (Dobos Reference Dobos2007). Those who were members of the Hungarian Parliament as nationalities were selected by the communist party as they had quasi-reserved seats after the turn of the 1950s–1960s. The parliament itself, however, did not work as a democratic institution, since its members were not elected in a democratic way and it met only for few days a year. As Péró Lásztity, Serbian member of the Minority Roundtable (MRT) during the 1990s, observed: “During communism some nationalities were supported by the communist government, received significant funds and could even send a representative to parliament, although that parliament did not work as a democratic multiparty parliament” (Interview HUN-2.1.8 with Péró Lásztity, 8 September 2015, Budapest). Similarly, in the later parliamentary debates on the minority law during 1992, Róbertné Jakab, an ethnic Slovak MP in Hungary’s communist-era parliament, recalled how, in 1985 and 1987, her proposals geared to ending minority assimilation in Hungary were peremptorily dismissed from the agenda of a party meeting with the phrase “don’t you go talking about Slovaks here!”Footnote 9

As the Hungarian government became more conscious of past mistakes in minority policy during the 1980s, it also began to acknowledge the Roma as an ethnic minority group, whereas previously they had been treated merely as a socially marginalized category within the ethnic Hungarian population (Dobos Reference Dobos2007). However, until the turn of the 1980s–1990s, the Roma still did not have the same status as the other minorities:

In this period the communist powers repulsed our claims, they persecuted us, they stigmatized us as nationalists but as an answer to this they established the Cigany organizations of the communist regime—the Democratic Associations of the Hungarian Ciganys and the National Cigany Council, the Cultural Association of Hungarian Ciganys—as national-level organizations, and these institutions dissociated themselves from claiming the rights of the Hungarian Ciganys. These Cigany organizations were hand operated, controlled by the communists and politics of the time.

(Interview HUN-2.1.5 with Jenő Zsigó, former president of the Roma Parliament, December 1, 2015, Budapest)Talk of enacting a specific minority law had begun already in 1979, when a draft was prepared by Professor Mihály Samu at the Law Faculty of Eötvös Loránd University. This, however, was rejected by the then–party leaders, as was a later draft prepared by the legal expert András Baka in 1988 (Bodáné Pálok Reference Bodáné Pálok1993). In 1989 a further draft was formulated under the leadership of the deputy minister of Foreign Affairs, Csaba Tabajdi, but this did not find support either among other ministries or minority leaders before the first free parliamentary elections were held in 1990 (Bodáné Pálok Reference Bodáné Pálok1993). It was at this time that Hungary was undergoing its peaceful change of regime and beginning its transition to becoming a democratic state, thereby finally paving the way for substantive discussions on a new legislative basis for minority policy.

The Parliamentary Debate on the 1993 Minority Law

After 1990, the new democratic government continued to work on the minority law, which was submitted to the Parliament in June 1992 and was accepted a year later, in July 1993. The Hungarian Minority Law elicited broad international interest and has been relatively well surveyed elsewhere (see, for example, Bindorffer Reference Bindorffer2011; Csefkó and Pálné Kovács Reference Csefkó and Kovács1999; Dobos Reference Dobos2007, Reference Dobos2011; Eiler Reference Eiler and Tóth2005; Kállai Reference Kállai2005; Koulish Reference Koulish2003; Kovats Reference Kovats and Cordell1999; Pap Reference Pap2015; Schafft Reference Schafft1999; Szabó Reference Szabó and Tóth2005; Vizi Reference Vizi, Malloy, Osipov and Vizi2015; Walsh Reference Walsh2000; Waters and Guglielmo Reference Waters, Guglielmo and Micgiel1996). These studies present the historical context of the law and analyze how its implementation affected national minorities and the Roma in particular. There are studies among the historical analyses of minority politics which do not investigate the phase of the parliamentary debates (Győri Szabó Reference Győri Szabó1998; Tilkovszky Reference Tilkovszky1998), while other works limit themselves to a brief summary of the key discourses within them, as part of a broader discussion of the legal system and historical perspectives (Bindorffer Reference Bindorffer2011; Bodáné Pálok Reference Bodáné Pálok1993; Kállai Reference Kállai and Fedinec2013; Szabó Reference Szabó and Tóth2005). Only very few studies actually focus on the parliamentary debates themselves. Tóth (Reference Tóth2008) analyzes the political intentions of the MPs representing different political parties, pointing to a minority-majority agreement and an arrangement among the majority elite over the law and highlighting the importance of obtaining international support. Koller (Reference Koller2011) examined in her PhD dissertation how the concepts of nation and external and internal minorities were discursively constructed during the parliamentary sessions. Other scholars have used the parliamentary debates to highlight the frequent references made by MPs to Hungarian minorities abroad (see, for example, Majtényi Reference Majtényi and Bloed2007a). However, with the abovementioned exceptions of Tóth (Reference Tóth2008) and Koller (Reference Koller2011), a comprehensive analysis of the debate has not yet been undertaken. Further content analysis and interviews both reveal that a wider range of issues emerged during the debates. This suggests a need to view the Hungarian minority policy as a wider whole, focusing on and critically assessing its various dimensions and components.

Analysis of the Debate

For the purposes of this article, we confine ourselves to the analysis of the parliamentary debates preceding the enactment of the law, with the aim of determining the main driving factors behind it and how these corresponded with the interests of different stakeholders—in other words, how the parliamentary debates reflected the political motivations and mood of that period. This section is based on a content analysis of the parliamentary debates of the minority law in 1992 and 1993 (indicated in bold italic letters) and interviews conducted with former MPs (indicated in italic letters).

In addition to the aim of preserving minority languages and cultures, or even creating a diverse, multicultural environment (Majtényi Reference Majtényi2007b, 178), the existing literature primarily identifies three further key factors driving the creation of a new minority law:

1. As noted above, the aim of improving the conditions of Hungarians living as minorities abroad by providing an example for neighboring countries (see also Dobos Reference Dobos2011; Eiler and Kovács Reference Eiler, Kovács and Gál2002; Kállai and Varjú Reference Kállai, Varjú, Gyulavári and Kállai2010)

2. A desire to court/foster closer ties with international organizations by:

a. Demonstrating a readiness to adopt Western standards (Eiler Reference Eiler and Tóth2005; Eiler and Kovács Reference Eiler, Kovács and Gál2002)

b. Preventing criticism of the treatment of minorities in Hungary (Dobos Reference Dobos2011; Kállai and Varjú Reference Kállai, Varjú, Gyulavári and Kállai2010)

3. Compensating the previously discriminated Roma by making their legal status equal to that of Hungary’s other recognized minorities (Dobos Reference Dobos, Salat, Constantin, Osipov and Székely2014; Majtényi and Majtényi Reference Majtényi and Majtényi2016)

The Main Topics of the Debate

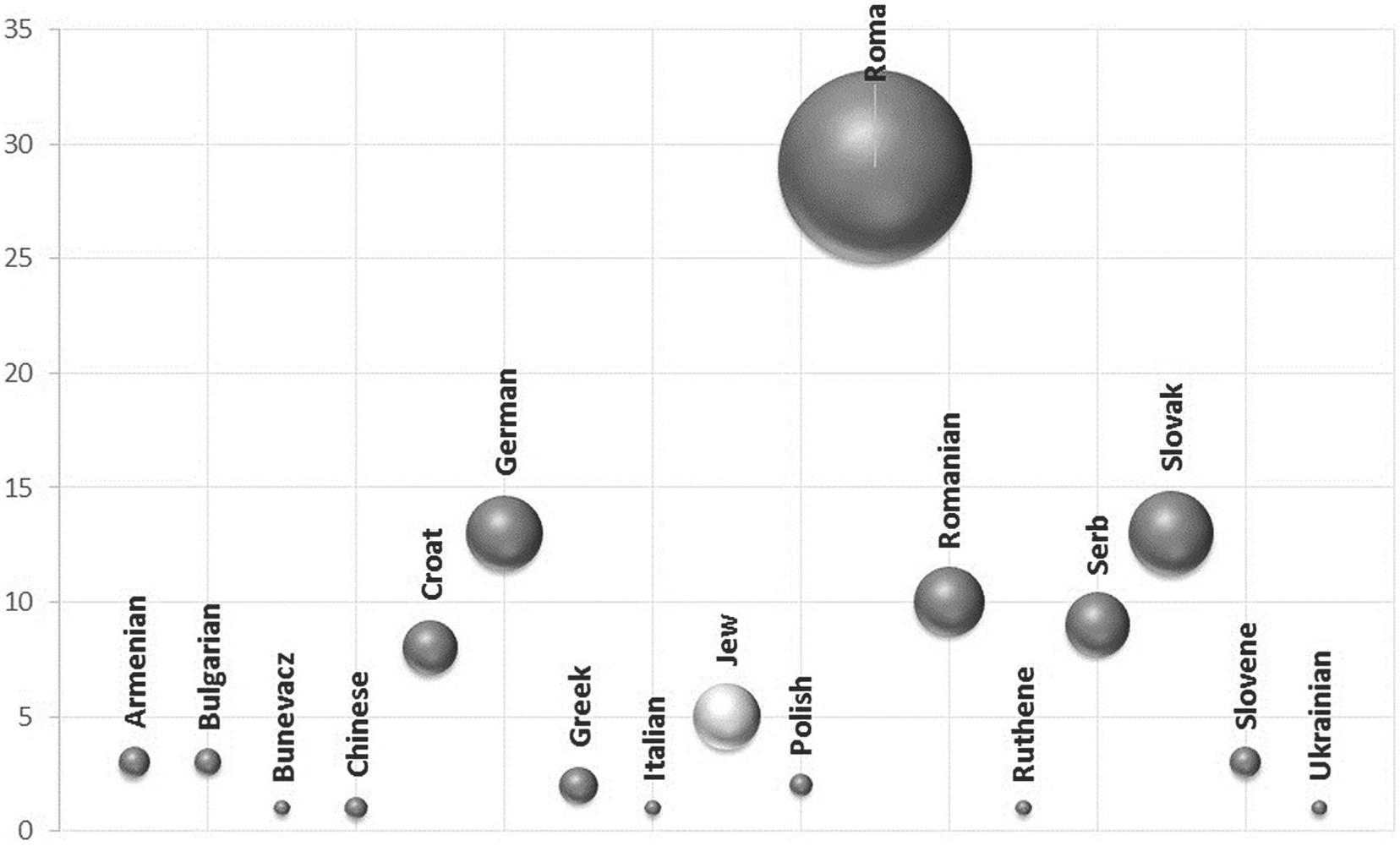

A content analysis of the 66 speeches made during the parliamentary debates of 1992 and 1993 shows that the most frequently mentioned words were “minority,” “Hungarian,” “national,” “ethnic,” “law,” and “self-government.” The most frequently mentioned nationalities were the Roma, which were discussed more than twice as often as the second most-cited ethnocultural groups, the Germans and the Slovaks (see Figure 1). This clearly demonstrates that the Roma issue was an important one, although looking at this figure in isolation we cannot identify in what context this word was mentioned. However, later, when we carried out a deeper analysis of the speeches, we found that these references reflected MPs’ concerns about the situation of the Roma at the time and whether this law would fulfil their desire to integrate this ethnocultural group into mainstream society.

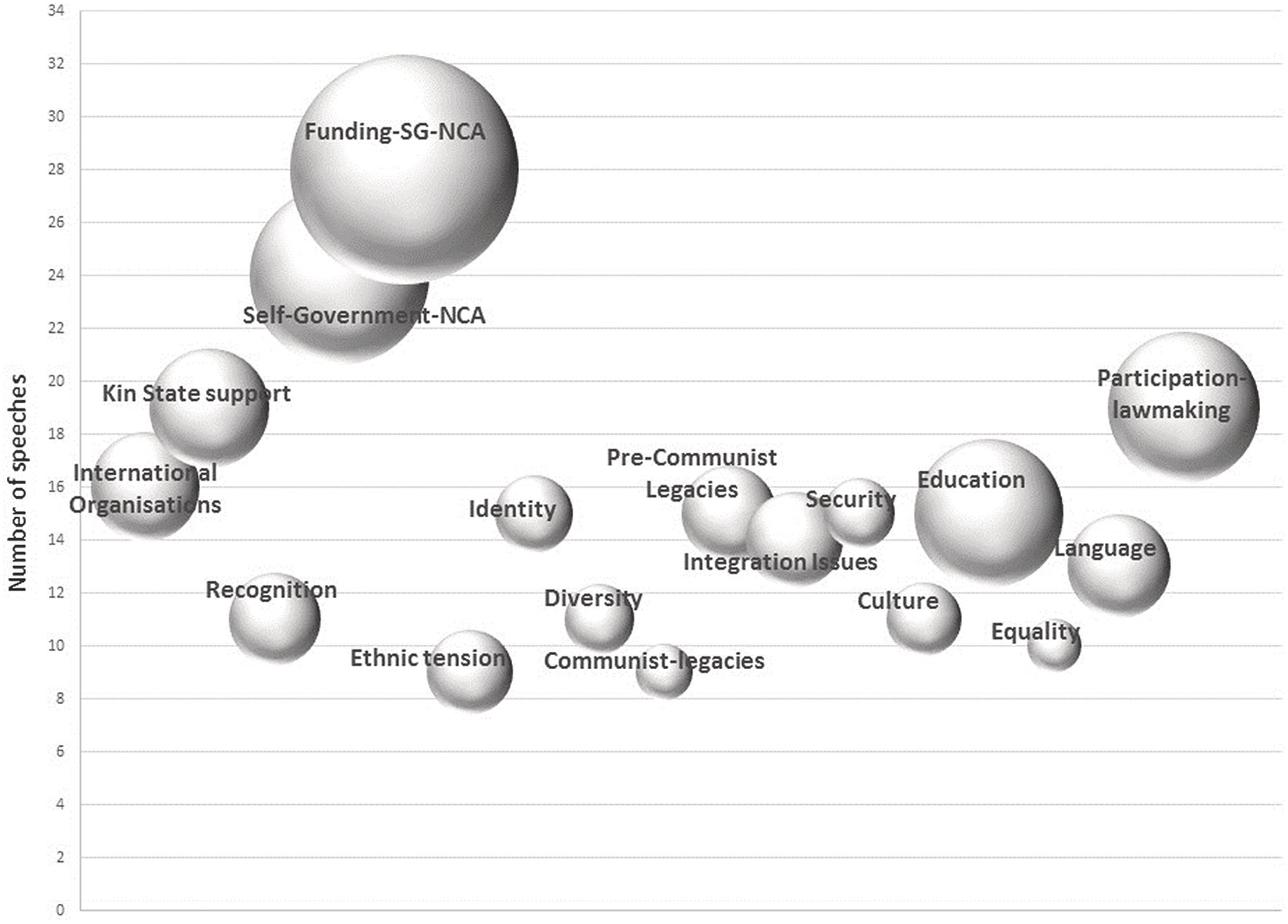

The most frequently discussed topics during the debates were the system of self-government and associated issues of practical and financial feasibility (Figure 2). Here it was seen as very important to create an institutional framework that would allow for the representation of national minorities’ interests.

Figure 2. The main topics during the parliamentary debates.

Self-Government and Finance

There were two main approaches regarding the conceptualization of the minority law during the preparation phase: the “liberal” and the “autonomist” (Eiler Reference Eiler and Tóth2005; Vizi Reference Vizi, Malloy, Osipov and Vizi2015). The representatives of the national minorities supported the latter autonomist conception, based on principles of non-territorial self-government:

The minorities preferred this [self-governmental] form. There was some suggestion by the government of considering other forms, like NGOs, but the minorities strongly stood for the self-government systems and they made a political issue of it. So we [the Committee of Human Rights, Minority and Religious Issues] accepted this.

(Interview HUN-2.1.3 with Gábor Fodor, MP, FIDESZFootnote 10 – now president of the Liberal Party, September 10, 2015, Budapest)Territorial autonomy would not have worked because the minorities live dispersed within Hungary. NGOs also were not preferable because their numbers had grown in the early 1990s and their leaders were not elected. Furthermore, many NGOs had continued from the Kadar regime in which their leaders were appointed by the Patriotic People’s Front—so it would not have been a popular model to adopt; we wanted a legitimate system, so that in every settlement people could elect their own members.

(Interview HUN-2.1.2 with Antónia Hága, ex-MP, SZDSZ,Footnote 11 September 3, 2015, Budapest)The members of parliament understood that one of the weakest points of this law would be its financial arrangements, which they also discussed in great detail. Members of the opposition parties made more speeches (18) voicing concerns about financial issues than members of the ruling coalition (10). Thus, Zsolt Németh, MP for the opposition FIDESZ party, asked “Who is going to pay? The financial basis of the minority self-government has not been defined in this draft law.” Even members of the governmental parties expressed concerns in this regard, as seen in Imre Sipos’s (MP, FKgPFootnote 12) profession of “serious doubts about the financial guarantees in this law” and Ferenc Vona’s (MDFFootnote 13) claim that “I am sure that this law will work in a different way from what we assume now … because of its financial problems.”

In spite of these reservations, the government did not initiate any further measures to address the envisaged financial problems. Obviously at the time they did not know how many minority self-governments would be established during the implementation of the law. According to one of our respondents, the government believed that if problems arose in future, the law could simply be amended.Footnote 14

Kin-State Policy, Minorities’ Participation and Compliance with International Organizations’ Expectations

The second most discussed topics during the debates were Hungary’s kin-state policy agenda, minorities’ participation in the law-making process, and compliance with international organizations’ expectations. The content of these speeches addressed moral responsibility and how the new law could provide a good model for countries with minorities. We cannot find substantial differences between the numbers of speeches of the governmental and nongovernmental parties’ MPs, but overall the pro-government representatives of the House had significantly lengthier statements regarding this topic.

The kin-state policy dimension was never hidden as a motive for a new minority law in Hungary, as seen in the following statement by László Kováts (FgKP):

There is no state with the moral authority to require other countries to give rights to their minorities if it does not do the same for its own minorities. I think I do not need to emphasize the truth and importance of this [law] for the Hungarians who live on the other side of the border.

Indeed, some MPs argued openly that the minority law could be used to lobby for change to the minority policies of neighboring countries:

But we can provide an example which will be an appropriate answer to Marosvásárhely [Târgu Mureș], Kórógy [Korođ] and Pozsony [Bratislava]Footnote 15 and we can get acknowledgment from the world’s most democratic powers as we had in 1849.

(János Varga, MDF)Those who were involved in the legislative process at the time of the creation of the new minority law in the early 1990s recall this period as a liberal democratic era. They also foresaw the role of international organizations—which they hoped could also be persuaded to improve the situation of Hungarians living in the neighboring countries—as very important:

On the one hand the liberal democratic atmosphere was dominant in public and political life then and this is why people tended to support the self-government system, and this attitude was dominant toward minorities as well. From the political right wing it was also important because they thought that there were serious problems in the neighboring countries with minority issues where Hungarians were living as minorities…. That Hungary could raise its voice on the international stage for Hungarians’ rights living abroad in minority, was important. There was also a political consensus in the belief that Hungary should be able to integrate into international organizations, like NATO and the Council of Europe, as soon as possible and that this would be facilitated by Hungary demonstrating the granting of improved rights to its minorities. There was a demand from the minorities themselves as well but minorities in Hungary are less significant in numbers than in the neighboring countries; it was not a huge political issue internally. We became a member of the Council of Europe in 1991 and I was one of the first delegates from Hungary. I remember that Hungary argued that we were trying to introduce a new minority law whilst the neighboring countries were deficient in not having equivalent legislation in place.

(Interview HUN-2.1.3 with Gábor Fodor, MP, FIDESZ—now president of the Liberal Party, September 10, 2015, Budapest)For the government of the time, it was thus important both to provide an example to the neighboring countries and to prove to the West that Hungary had become a democratic country where minorities were well protected, while simultaneously seeking support from the West to realize this agenda both within and outside Hungary. One-quarter of the speeches delivered during the debates discussed the importance of cooperation with international organizations and the positive feedback already received from them. More than 60 percent of these speeches were given by MPs belonging to the ruling coalition.

Although some significant topics in the parliamentary debates—such as participation in law-making and education (see Figure 2)—did not explicitly refer to Hungary as a kin-state, it is easy to observe the implicit connection: mention of the minorities themselves being deeply involved in the law-making process, minority education, and even security/reconciliation issues can all be seen as a message to neighboring countries that they should follow this example. However, education was also an important topic in its own right, because national minorities’ education had been neglected under communism; a system for how to operate these schools had to be re-established.

Recognition and Registration

There was also a debate around the question of recognition. First of all, lawmakers had to decide which ethnocultural groups could become the object of the law and the kind of criteria that should apply to those nationalities eligible to form minority self-governments. It was ultimately decided to stipulate that an ethnocultural group had to have lived on the territory of Hungary for 100 years or more. While there was not unanimous agreement over this, it did not trigger any significant debate. Csaba Tabajdi from the opposition MSZP argued that Hungary had a different territory 100 years ago, and the criterion was therefore based on something that no longer existed. He instead suggested setting the criterion at somewhere between 40 and 70 years. Some MPs from the parties of the government coalition (Sándor Kávássy from FKgP, Ferenc Vona and János Varga from MDF) also disagreed with this interval and recommended having a shorter period for the required timespan.

The other question was to which ethnocultural groups the category of “national minority” should be applied. During communism, the Germans; Slovaks; Romanians; and Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (under the common label “Southern Slavs”) were recognized as nationalities, while later other, previously nonacknowledged communities like Bulgarians, Greeks, or Poles, which comprised both established national minority and recent immigrant elements among their populations, also made claims for recognition.

The roundtable was established by civil organizations with democratic orientation, and they were able to participate in a democratic public sphere. At the beginning the traditional nationalities and Roma were part of the roundtable. There was a meeting where members of other nationalities which were between immigrant and nationality status were also invited, in order to neutralize the standpoints of the MRT. But we solve the problem by inviting them to join the MRT. And they did, so then the government had to consider at least at some level the opinion of the MRT.

(Interview HUN-2.1.8 with Péró Lásztity, member of the MRT, September 8, 2015, Budapest)Roma people were seen as ethnic minorities and Jews as a religious group. This latter distanced themselves from the MRT at the early stage of its formation.

And later when we were discussing the draft law, the Jews received an order probably from the Association of the Hungarian Jews that they should not participate and they stepped out from the roundtable.

(Interview HUN-2.1.9_ANON with former member of the MRT, September 11, 2015, Budapest)“… the Jewish elite—who realized that they do not want to be identified as a minority group—favored identification as a religious group.

(Interview HUN-2.1.1 with Aladár Horváth, member of the MRT, September 10, 2015, Budapest)In 1992 they wanted to separate the Roma [from the other minorities], which had a logical reason because in the case of the Roma the language played less of a role in their identity than social issues, while in the case of the other minorities they were integrated into the Hungarian society but they were different in their language and customs [traditions].

(Interview HUN-2.1.9_ANON with former member of the MRT, September 11, 2015, Budapest)In Article 1 the law states that:

… for the purposes of the present Act a national or ethnic minority (hereinafter “minority”) is an ethnic group with a history of at least one century of living in the Republic of Hungary, which represents a numerical minority among the citizens of the state, the members of which are Hungarian citizens, and are distinguished from the rest of the citizens by their own language, culture and traditions, and at the same time demonstrate a sense of belonging together, which is aimed at the preservation of all these, and the expression and protection of the interests of their communities, which have been formed in the course of history.

There was a concern that formulating the law in this way could mean the exclusion from the category of minority the estimated 80 percent of the Roma population whose mother tongue was Hungarian. János Varga (MDF), for instance, asked “but how will this law apply for the Roma people? Their own native tongue is the Romani language but this has not been spoken by the Beash nor the Roma who only speak Hungarian.”

The law eventually recognized 13 national and ethnic minorities of Hungary, including the Roma.Footnote 16 A further question was raised, however, about registration: How would it be possible to implement a law for groups whose members are unknown and cannot be officially identified? This reflected a strong underlying opposition to registration on the part of the MRT and MPs who belonged to national minorities.Footnote 17 But without the registration of the subjects of the minority law, nonminorities would also be able to vote and be elected. This led later to the so-called “ethno-business” phenomenon (Dobos Reference Dobos2007; Smith Reference Smith and Kántor2014).

Pre-Communist Legacies

A further historical element was also frequently brought up during the debate: namely, pre-communist legacies were repeatedly cited as good examples of how Hungary tried to manage its minorities during the 19th century. In the immediate post-communist era, it was thus politically expedient to imagine that Hungary treated its minorities well in the days when their numbers had been appreciably higher. As noted earlier in this article, however, national minority policy in the pre–First War period can in many ways be classed as a failure. The minority law in 1868 and the more general policy toward the nationalities after the 1867 Compromise, while relatively modern and liberal for the time, were not really implemented, and subsequent governments’ policies became increasingly nationalistic and disadvantageous for the nationalities of 19th century Hungary (Ács Reference Ács1986).

Roma Integration

Roma integration was also discussed during the parliamentary debates but was clearly seen as an intractable issue still awaiting solution. Csaba Tabajdi (MSZP) exemplified this view, when he claimed that:

… in the case of the Hungarian Roma there are such serious social problems that it is not possible to solve those through this [minority] law, it would require a special Roma program to manage this crisis, because in many cases these social issues (like unemployment and social deprivation) are more serious than the ethnic issues.

The Roma MPs, who were elected as members of different mainstream parties, commented on these issues as well, bringing attention to the main problems affecting Roma. In this regard, Tamás Péli (MSZP) asserted that “the right for self-organization and empowerment of Roma is only a necessary but not a sufficient condition in order to escape from a social problem which is a threat to its [the Roma’s] physical existence. Its real interests and difficulties were always swept under the carpet.” Péli’s view concurred with that of other Roma representatives such as Aladár Horváth (SZDSZ), who warned that:

… the serious problems caused by the economic crisis, the tendencies of racism and the general poverty in which we [Roma] live … are leading to racial prejudice and we know well that this will not be solved by this minority law. But we need a minority law which will have an impact on other laws, on social and economic laws and provide guarantees and a framework for minorities’ welfare, in this case for the Roma, so that they become part of the decision-making process, simply that they would integrate into Hungarian society.

Despite these concerns, lawmakers did not pay sufficient attention to the different characteristics of Hungary’s national minority groups. These dissimilarities mean that it is almost impossible to devise a single law that would allow for the same level of cultural autonomy and benefit for every nationality. The 1993 minority law, however, envisaged the same framework for national minorities that were both demographically and culturally diverse, a fact which accounts for some of its many failings.

Conclusion

In this article, we have used parliamentary debates as well as interviews with key actors in order to reveal the primary motives and claims behind the adoption of Hungary’s much-discussed 1993 minority law. As we observed at the outset, the dominant view expressed in the relevant literature from the 1990s onward has been that the law was motivated primarily by concerns regarding Hungarian minorities living in neighboring countries. The present analysis confirms that support for co-ethnics abroad was certainly an important motivating factor during the preparation of the law. Nevertheless, one should be wary of claiming on this basis that it accorded greater importance to external considerations at the expense of domestic ones.

In our view, far more attention needs to be paid to historical and communist legacies, especially given the presence within the post-communist region of several constraints hampering the development of a tolerant, minority-friendly institutional framework and the realization of minority interests. Chief among these has been the tendency toward the construction of modern ethnicized nation-states that are parsimonious toward their internal minorities. In the case of Hungary, the preparation of the minority law did involve representatives of the newly formed Minority Roundtable (albeit late in a process which had antecedents in the pre-communist period and had begun in 1988, before even the first democratic elections). Yet, although progressive and extensive provisions on NTA were adopted, and in some cases minority organizations were successful in representing their interests, in other instances their demands either could not be fully met, or could not be realized at all, and sometimes their participation in the law-making that crucially affected their lives became very limited.

The nature and outcome of this process are instructive; had Hungary’s aspirations as a kin-state been the main driver behind the law, one might have expected the state—as more prone to accept and accommodate ethnic diversity—to have left more room for the demands of domestic minorities. As shown above, however, the key points of discussion during the parliamentary debates mainly related to the structure of NTA institutions, their financing, and the situation of Hungary’s Roma. These domestic issues figured prominently alongside discussion of Hungarian minorities abroad and meeting the requirements of international organizations. As a result, we can conclude that as a consequence of the communist legacy and the continued and institutionalized dominance of the overwhelming Hungarian ethnic majority, the increasingly complex Hungarian model has remained rather paternalistic. This top-down style of governance of minority protection in which foreign considerations also played an important role compared to power-sharing and financial issues, has been less receptive to minority voices. Consequently, the 1993 minority law showed serious flaws and was later amended several times before being replaced by the 2011 law on the Rights of Minorities. Yet, given the increasing role of ethnicity in contemporary Hungarian politics, it is questionable whether the overall features of policy-making have changed over time at all.

Financial Support.

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council under Grant [number ES/L007126/1; data collection number 852375] and the JÃnos Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Disclosure.

Authors have nothing to disclose.