The Mediterranean diet (MD) is regarded as a prototype model for healthy eating and has generally been associated with longevity. A growing body of scientific evidence suggests that the MD is protective against several morbid conditions including CVD, diabetes mellitus, arthritis and cancer(Reference Trichopoulou, Bamia and Trichopoulos1–Reference Matalas, Zampelas, Stavrinos and Wolinsky7). In particular, adherence to the traditional MD has been associated with lower overall mortality as well as with lower CVD mortality(Reference Trichopoulou, Bamia and Trichopoulos1, Reference Trichopoulou, Costacou, Bamia and Trichopoulos4). Although studies on children are limited and the vast majority of scientific publications refer to adults, emerging evidence from studies on children suggests that the MD may be a health-promoting factor for children, as well.

A study conducted in Spain among 3166 youngsters aged 6–24 years has shown that the MD is a nutritionally rich diet for children(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas, Garcia, Perez-Rodrigo and Aranceta8). Degree of adherence to the MD was assessed by a tool developed by the researchers for this purpose, the KIDMED index, and was positively related to better nutrient intake. Moreover, two recently published studies concluded that the MD has a beneficial effect on asthma and allergy(Reference Chatzi, Apostolaki, Bibakis, Skypala, Bibaki-Liakou, Tzanakis, Kogevinas and Cullinan9, Reference Garcia-Marcos, Canflanca and Garrido10). In the first study(Reference Chatzi, Apostolaki, Bibakis, Skypala, Bibaki-Liakou, Tzanakis, Kogevinas and Cullinan9), the diet of 690 children in rural Crete, aged 7–18 years, was assessed by a slightly modified version of the KIDMED index. The investigators compared the scores derived via the KIDMED index with those derived via another tool that has been developed for adults, the MD Score introduced by Trichopoulou et al.(Reference Trichopoulou, Costacou, Bamia and Trichopoulos4) (which was modified to exclude alcohol presumed protective, rather than detrimental, effect of dairy products), and found that both scores gave similar results(Reference Chatzi, Apostolaki, Bibakis, Skypala, Bibaki-Liakou, Tzanakis, Kogevinas and Cullinan9). In the second study, conducted in Spain among 20 106 children aged 6–7 years, MD was assessed by a modified version of the MD Score mentioned above(Reference Garcia-Marcos, Canflanca and Garrido10).

Two previous small Italian studies(Reference Avellone, Di Garbo, Panno, Cordova, Abruzzese, Rotolo, Raneli, De Simone and Strano11, Reference Ferro-Luzzi, Mobarhan, Maiani, Scaccini, Virgili and Knuiman12) have reported that adherence to the principles of the MD, as defined by Italian experts, leads to favourable lipid profiles in children on the one hand(Reference Avellone, Di Garbo, Panno, Cordova, Abruzzese, Rotolo, Raneli, De Simone and Strano11), and that deviation from the MD is associated with unfavourable lipid profiles, on the other(Reference Ferro-Luzzi, Mobarhan, Maiani, Scaccini, Virgili and Knuiman12).

The MD prototype is used as an educational tool in Mediterranean as well as in some non-Mediterranean countries in order to promote healthy eating habits among children. Despite the widespread use of the MD prototype in public health programmes in Cyprus, to the best of our knowledge, there are no data assessing the dietary habits and adherence to the MD among Cypriots, including children.

The objective of our study was to evaluate the quality of Cypriot children’s diet by assessing the degree of adherence to the MD and to examine how the intake of various food groups varies with different levels of adherence to the MD.

Subjects and methods

Study population

A total of 1589 children of the 4th, 5th and 6th grade (9–13-years-old, mean age = 10·7 (sd 0·98) years) in twenty-four randomly selected primary schools in Cyprus were identified as eligible participants, while 1140 agreed to participate (72 % participation rate, 532 boys and 637 girls), representing 3·7 % of the total population of school-age children (participation ranged from 2·6 % in the urban area of Nicosia to 7·8 % in the rural area of Paphos). Sampling was stratified multistage design and was based on the number of students in each of the five provinces of the island (data are not published, printed data available on request from the Department of Primary Education) and by place of residence (place of school was used as a proxy), urban or rural, as provided by the Cyprus Statistical Service(13).

In the first step, at least four schools were selected from each of the four provinces and two from the fifth as most of it is not inhabited by the population due to occupation. At least two of the selected schools in each province were based in an urban area. Schools in urban areas were selected so that they included at least one school in the upper quarter of socio-economic status (SES) and at least one school in the lower quarter, because SES is one of the most powerful confounding factors to which many of the differences between urban and rural areas are attributed(Reference Meredith14). Schools in rural areas were selected according to the geomorphologic classification, countryside/mountainous area, to control for the confounding factor of geomorphologic characteristic, which might interact with the rural environment(Reference McMurray, Harrell, Bangdiwala and Deng15). Schools in rural areas could not be divided by SES, as in most rural areas in Cyprus there is only one school. The criterion of geomorphologic characteristic, on the other hand, could not be used in urban areas, as in Cyprus all urban areas are located, more or less, on the sea level.

At the last stage of sampling, whole school classes were selected. Whenever the school was small (up to two classes from each grade), all children from target grades were contacted, whereas in larger schools classes were selected based on availability and cooperation. The study was approved by the Ministry of Education and Culture (Department of Primary Education). Informed consent forms were signed by the corresponding parent or guardian of each participating child.

Dietary assessment

Dietary assessment was based on a semi-quantitative FFQ, consisting of 154 food items including all of the commonly used foods of the local Greek-Cypriot cuisine. Two supplementary sections, which evaluated other aspects of dietary habits, were attached to the FFQ: a Food Groups Frequency Questionnaire (FGFQ) and a Short Eating Habits Questionnaire (SEHQ). The first evaluates children’s weekly consumption of major food groups and the second assesses information on basic dietary habits (such as breakfast intake, eating while watching TV, religious fasting practices, etc.). Questions regarding the type of fat used in cooking and frying and removal of visible fat in meat and poultry were answered by parents via a short questionnaire that was attached to the consent form.

The children’s FFQ was administered to all students of each class during school hours, from February to June of 2005, by the principal investigator, according to a written protocol describing a standardized methodology for data collection. On the basis of the FFQ, all participants were asked about their usual frequency (average over the last year) of consumption of the foods, which were classified into fifteen groups (milk and dairy, eggs and products, meat and mince, delicatessen and smoked meat, fish and seafood, pasta, bread and cereals, potatoes, legumes, fresh legumes and olives, nuts, miscellaneous (mixed dishes, confectionery, pastries, ethnic food, cakes and biscuits, other snacks), drinks, fruits and vegetables).

Response categories for all food items, except items from fruits and vegetable (F&V) groups, ranged from 1/d, 2–3/d, 4–5/d, ≥6/d, 1/week, 2–4/week, 5–6/week, 1–3/month to seldom/never, whereas the scale for F&V intake consisted of eight response categories, ranging from 1/d, ≥2/d, 1–2/week, 3–4/week, 5–6/week, 1/month, 2–3/month to never. Standard size of food portions that could be easily understood by children, such as F&V, was included in the questions, whereas food models from the USA Dairy Council(16) and NASCO(17) were used for all other food groups as children’s aids to visualise the regular portion. Food models were also used to help children recognize/identify unknown food items.

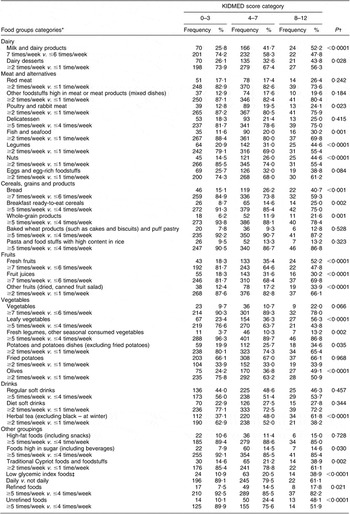

A total of 154 food items from the FFQ were collapsed to thirty-three defined food groups (Table 2), which may have practical importance in daily diet and daily clinical practice. In addition, the above groups may be closely approximated to food groups that have been previously reported in the literature. Some individual food items were preserved as a single group because they were suspected to represent distinct dietary patterns (olives, fried potatoes, regular and diet soft drinks, herbal tea, poultry and hare/rabbit meat).

Assessment of Mediterranean diet patterns

The KIDMED index (Mediterranean Diet Quality Index for children and adolescents) was used to evaluate the degree of adherence to the MD. The index(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas, Ngo, Ortega, Garcia, Perez-Rodrigo and Aranceta18) includes sixteen components, which are based on the principles of the MD and summarise a score that ranges from 0 to 12. More specifically, the KIDMED index presumes the daily consumption of at least one serving for F&V, while consumption of at least two servings from each group is preferred. Level of recommended consumption for dairy products is at least three servings daily: one dairy product in breakfast and at least two servings of yoghurt and/or cheese during the day. Daily consumption of grains and cereals is recommended during breakfast, while pasta or rice should be consumed at least five times per week. A weekly consumption of at least two to three servings is presumed for nuts and fish, and of at least two servings for pulses. Olive oil is recommended for culinary use, but no frequency is suggested. Dietary behaviours that are viewed as detrimental and alien to the principles of the MD include the frequent intake of sweets and candies (we defined this as more than twice daily), the use of commercially baked goods and pastries in breakfast, having meals in fast-food outlets and the abstainance from breakfast.

According to KIDMED scoring, 0–3 reflects a poor diet in relation to the MD principles, whereas values 4–7 and values 8–12 correspond to average and good adherence to the principles of the MD, respectively. Our questionnaire did not include the original KIDMED questionnaire; rather, we recoded questions from the FGFQ, the SEHQ and the short questionnaire that was completed by the parents, in order to derive the response categories of the KIDMED questionnaire.

Assessment of other co-variables

Sociodemographic variables

Data on sociodemographic characteristics such as age, gender, place of residence and family size were provided by the children. Information on the parents’ educational level, income and parents’ occupation were collected via a short questionnaire that was completed by the parents. Socio-economic status was assigned based on the parents’ educational level and occupation.

Physical activity variables

Children responded to a 32-item, semi-quantitative questionnaire, which assessed both organised and free-time physical activity. Principal component analysis (varimax rotation) was employed to extract the main factors out of twenty-one variables from this questionnaire, assessing children’s frequency and duration of physical activity.

Eight factors emerged as important, explaining approximately 63 % of the total variance in children’s physical activity and sedentary patterns. These are ‘physical activity and sports after school’; ‘home chores and outside home chores, aerobics, gymnastics, sports’; ‘Sports for all, after school activities (except sports)’ ‘video, electronic games and computers’; ‘watching TV, video and DVD’; ‘homework and private lessons’; ‘theatre cinema, use of mobile phone’; ‘afternoon sleep, less private lessons’.

Anthropometry and obesity index

Children’s height and weight were reported by parents. Obesity and overweight among children were calculated using the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) age- and sex-specific BMI cut-off criteria(Reference Cole, Bellizzi, Flegal and Dietz19). Parents’ obesity was also calculated from self-reported values of body weight and height. Parents’ overweight and obesity was assigned for BMI = 25–29·9 kg/m2 and BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean (sd), whereas categorical variables are presented as absolute and relative frequencies. Normality of variables’ distribution was tested by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Associations between normal distributed variables were tested ANOVA, with Bonferroni correction to account for the inflation of type-I error due to multiple comparisons made, whereas the Kruskal–Wallis test was used for non-normally distributed continuous variables. Associations between categorical variables were tested by contingency tables and the χ 2 test.

The association between the frequencies of consumption of various food groups and the level of adherence to the MD (as assessed by the KIDMED score) was tested by applying the χ 2 test. We further applied multiple logistic regression analysis evaluating the association between the levels of adherence to the MD (as assessed by the KIDMED score) with the frequencies of consumption of several food groups adjusted for potential confounders (age, gender, place of residence, children’s BMI, SES level and physical activity).

All reported P values are based on two-sided tests and were based on the 0·05 as the level of statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences statistical software package version 13·0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Characteristics of the sample

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study population for boys and girls, by level of adherence to a pattern of eating consistent with the MD, as assessed by the KIDMED score.

Table 1 Selected demographic and lifestyle characteristics of the study sample, by KIDMED score

PCA, principal components analysis.

Continuous variables (e.g. age) are presented as mean (sd) and categorical variables (e.g. socio-economic level) as frequencies and percentages.

The Bonferroni rule was applied in order to account for multiple comparisons.

Only minor differences were observed among the three groups of adherence to the MD between the two genders. It should be noted, however, that a significant inverse association between obesity status (normal weight v. overweight/obese) and the KIDMED score categories was revealed in girls, while in boys this tendency did not reach the level of statistical significance (Table 1).

Similarly, an inverse relationship between the KIDMED score and the frequency and duration of watching TV, video and DVD was observed in boys, while in girls this trend did not reach statistical significance.

Level of adherence to the Mediterranean diet

Overall, only 6·7 % of the sample was classified in the highest category of the KIDMED score, whereas more than one-third of the sample had a low KIDMED score (Fig. 1). Even though no significant difference emerged by gender (P = 0·097), a higher percentage of boys (8·7 v. 5·3 %) were classified in the higher KIDMED score category, but at the same time, a slightly higher percentage of boys (38·5 v. 36·3 %) were also classified in the lower KIDMED score category (data not shown here).

Fig. 1 Level of adherence to Mediterranean diet, showing number and percentage of children, by the KIDMED score categories (![]() , boys;

, boys; ![]() , girls)

, girls)

Bivariate analyses

Associations between the frequencies of consumption of several food groups (as assessed by the FFQ) and levels of adherence to the MD are presented in Table 2. It should be pointed out here that the KIDMED score was derived from the two other diet assessment parts of the FFQ (a short FGFQ and an SEHQ) and the parents’ questionnaire, which are presented in the section ‘Subjects and methods’).

Table 2 Food consumption by frequency category by the KIDMED score category

*Frequency categories of each food group are described below each food group category. The first frequency category corresponds to the first row, while the second frequency category corresponds to the second row.

†From χ 2 test, df = 1.

‡Excluding foods with little or no carbohydrate.

Compared with the low adherers, those with higher adherence to a Mediterranean-type diet consumed more dairy products, poultry and rabbit meat, legumes, fish and seafood, nuts, bread, ready-to-eat cereals, whole-grain products, fruits, vegetables, fresh leguminous seasonal vegetables, potatoes (other than fried), olives, low glycaemic index foods, traditional Cypriot food and unrefined foods. It is noted however that high MD adherers also reported higher intakes of refined foods and foods high in sugar.

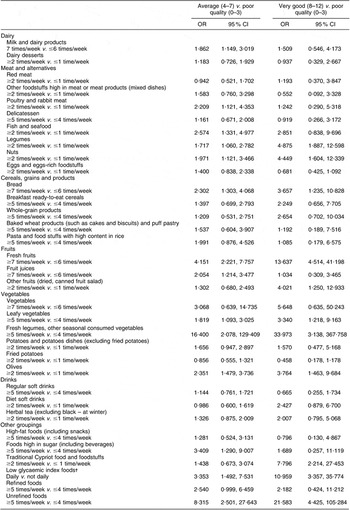

Multiple logistic regression analyses

After applying multiple logistic regression analysis in order to control for various potential confounders (i.e. children’s age, gender, place of residence, BMI class, SES level and physical activity) and estimate the effect size of any observed differences, several of the differences that bivariate analyses showed diminished. Specifically, compared with low adherers, children with at least an average KIDMED score were more likely to eat more frequently seafood and fish, legumes, nuts, bread, fruits, leafy vegetables, olives, low glycaemic index foods and unrefined foods. Consumption of most of the other groups mentioned above as significantly associated with the higher KIDMED score (and some other associations that were revealed by the multivariate analysis) did not follow a consistent pattern: i.e. average-degree adherers to the MD consumed dairy products, poultry and rabbit meat, fruit juices and potatoes – other than fried – more frequently than either high or low adherers (Table 3). Children in the highest KIDMED score category, on the other hand, consumed fruits from the ‘other fruits’ group and traditional Cypriot foods and foodstuffs more frequently than either low or average adherers. It should be noted that after the application of multiple logistic analysis, the positive associations between the KIDMED score and the frequency of consumption of refined foods and foods rich in sugar disappeared in the highest KIDMED score category, but not in the average KIDMED score category.

Table 3 Odds ratios and 95 % CI, derived from multiple logistic regression analysis, showing the association between adherence to Mediterranean diet and children’s consumption of selected food groups

*Adjusted for age, gender, socio-economic status, place of residence, BMI class, physical activity (as factors derived from PCA).

†Excluding foods with little or no carbohydrate.

Effect size of the observed differences was of medium to high order.

Discussion

The present study assessed Cypriot children’s diet quality by the level of adherence to the MD, as evaluated by the KIDMED score, and examined how intake of various food groups varied with the level of adherence.

Results have shown that the percentage of high adherers to the MD was only slightly above 6·5 %, whereas more than one-third of the children followed a poor-quality diet.

The dietary pattern profile that characterizes children who had the highest KIDMED score, after controlling for potential confounders, suggests that their diet is rich in seafood and fish, legumes, nuts, bread, fruits, leafy vegetables, olives, low glycaemic index foods and unrefined foods.

As mentioned above, only two other studies(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas, Garcia, Perez-Rodrigo and Aranceta8, Reference Chatzi, Apostolaki, Bibakis, Skypala, Bibaki-Liakou, Tzanakis, Kogevinas and Cullinan9) have evaluated the degree of adherence to MD in children. The first was conducted in Spain among 3850 children and youngsters aged 6–24 years. Results for the first age category of 2–14 years, which includes the age category of our sample, show that the distribution of the sample in the three KIDMED index categories differs substantially from our results, especially in the lowest and highest index categories: i.e. only 2·9 % had a very low KIDMED index results, whereas 48·6 and 48·5 % had intermediate and high index results, respectively(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas, Garcia, Perez-Rodrigo and Aranceta8, Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas, Ngo, Ortega, Garcia, Perez-Rodrigo and Aranceta18). The second study, which was conducted in Crete(Reference Chatzi, Apostolaki, Bibakis, Skypala, Bibaki-Liakou, Tzanakis, Kogevinas and Cullinan9) and evaluated adherence to MD according to a modified KIDMED index, included 690 children aged 7–18 years and reported results similar to ours in relation to the lowest KIDMED category: i.e. almost one-third (27·9 %) of the children had a poor MD score, but the percentage of children who scored at the highest score category was four-fold higher (28·5 % as opposed to 6·5 %).

In spite of the above differences with the other two studies, results of our study provide evidence of the association between level of adherence to the principles of MD and diet quality in children. In particular, we have shown that consumption of ‘healthful’ foods, such as fruits, vegetables, seafood, legumes, low glycaemic index foods, bread, nuts and olives is higher in children who have a higher KIDMED score (Table 3). There is a large body of published data that provides conclusive evidence that quality of diet, as assessed by food consumption, is highly correlated with the intake of nutrients in children(Reference Lee, Mitchell, Smiciklas-Wright and Birch20–Reference Räsänen, Lehtinen, Niinikoski, Keskinen, Ruottinen, Salminen, Rönnemaa, Viikari and Simell22). There is therefore substantial basis for arguing that adherence to the MD is independently associated with diet quality in children. Our results are in line with the findings of Serra-Majem et al. who reported that the adequacy of MD in the age range of 6–14 years increased with increased mean intakes of fibre and most of the vitamins and minerals while it decreased for inadequate intakes (<2/3 of the Reference Nutrient Intake) of Ca, folate and vitamin C in both genders and of Fe, vitamin B6, vitamins A and D in females(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas, Garcia, Perez-Rodrigo and Aranceta8).

It should be noted that no differences emerged between high and low adherers, with regard to the frequency of consumption of poultry, eggs, meat and delicatessen items, foods that according to the MD prototype should not be consumed daily or even weekly. We speculate that this outcome may be related to current dietary recommendations for children(23), which suggest a more frequent consumption of these foods (meat, poultry and eggs) than the MD scheme.

Furthermore, this may be related to the phenomenon of nutrition transition, the abandonment of the traditional MD and the high urbanisation which have occurred in Cyprus during the last decades(24, 25).

Strengths and limitations

We are aware of some limitations in our study. First, its cross-sectional methodology can only be suggestive of the relationship between adherence to MD and diet quality in children. In spite of this, the positive relationship between adherence to MD and better diet quality that we observed is consistent with the evidence provided in the literature. A second limitation relates to the fact that the various Mediterranean cultures exhibit variations in their traditional diets and there is an inherent difficulty in describing one uniform MD prototype. We have here used the criteria adopted specifically for children by a Spanish group of experts, feeling that they describe well the basic characteristics of all ‘MD’.

Strengths of our study include that it is a nation-wide study, the first in Cyprus, which reports on diet quality on any segment of the population and only the third internationally which reports on the adequacy of the MD in children.

Implications

Our results strengthen the position that the MD prototype represents a nutritionally adequate and balanced diet and could thus be used as an educational tool for promoting healthy eating habits in children. Further studies are therefore needed in order to evaluate interventions based on the MD as opposed to more ‘traditional’ ones, which are based on current recommendations for paediatric nutrition. Such interventions, besides the children, could also include parents and overall family environment, in order to assess their success when family environment is addressed, as opposed to just children. Evaluation should focus on differences between the two approaches with respect to the development of obesity, various biochemical indices and nutrition knowledge.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we report that preadolescent Cypriot children follow a diet of rather poor quality, as assessed by the principles of MD, and that adherence to a Mediterranean-type dietary pattern is, independent of potential confounders, associated with better diet quality. Future studies should further investigate this issue and collect more data among children in Mediterranean as well as in non-Mediterranean countries.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions: C.L. designed the study, performed the data analysis, interpreted the results and wrote the paper; D.B.P. supervised the design of the study, the statistical analyses, contributed to the presentation and interpretation of the results and critically reviewed the paper; A.-L.M. contributed to the presentation and interpretation of the results and critically reviewed the paper. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: The authors had no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements: The study was partially supported by ‘Charalambides’ dairies and by Cyprus Dietetic Association. Warm thanks to the participant children and their parents, to the Cyprus Ministry of Education & Culture (Primary Education Department) and to all the teachers who readily consented to carry out the study during school hours.