A medical second opinion referral is a process whereby an expert clinical opinion is sought, often through a tertiary centre, to aid in the diagnosis or treatment of a particular disorder. Seeking a second opinion in medical practice often carries negative overtones and as a result, there has been a recent tendency to overlook this source of help. The process may be initiated by a patient or their relatives on account of dissatisfaction with existing advice or treatment. Alternatively, legal factors may lead to further opinions being sought. In psychiatric practice it is common to manage patients in whom the diagnosis is not fully established or where a patient does not improve despite the use of established treatment. Studies consistently report similar rates of treatment resistance to initial pharmacotherapy of about 30% in both schizophrenia (Reference Conley and KellyConley & Kelly, 2001) and affective disorders (Reference AnanthAnanth, 1998). In this substantial proportion of patients in secondary care, a review by another psychiatrist may be helpful, even if the advice given is to continue the current approach. The practice of patient care being delivered by sector teams is likely to increase the usefulness of diagnostic and treatment reviews by ‘outside’ clinicians.

Despite these advantages, there is considerable reluctance to ask for second opinions among many senior clinicians. This may be because of insecurity, over-confidence, perceived isolation or the influence of the local culture in asking for help, or indeed giving help. Availability of local expertise in the clinical area of interest is also likely to be a factor. The reluctance to ask for help may be reflected in excessive time from referral to diagnosis. This in turn may be associated with treatment delay and worse outcomes. For example, the mean time taken from referral to diagnosis is often greater than one year in schizophrenia (Reference Johannessen, McGlashan and LarsenJohannessen et al, 2001), depression (Reference BlandBland, 1997) and dementia (Reference Cattel, Cambassi and SgadariCattel et al, 2000).

The existing literature on the predictors and value of second opinions is sparse. A substantial proportion of patients seek a second opinion after some kind of error or oversight has either failed to address their problem or exacerbated it. There is accumulating literature describing the frequency and characteristics of such medical errors. An important Australian study reported iatrogenic adverse event rates in 16.6% of patients, which included 13.7% who developed permanent disability and 4.9% who died (Reference Wilson, Runciman and GibberdWilson et al, 1995). Recently, Vincent et al (Reference Vincent, Neale and Woloshynowych2001) found that 11% of patients experienced a significant adverse event, over half of which were thought to be preventable by ordinary standards of care. In psychiatry, many studies show that a substantial proportion of people (perhaps the majority) treated with psychotropic drugs have side-effects. Although these side-effects are usually mild, they are the one important factor that contributes to reduced quality of life, non-adherence with medication and poor outcome (Reference HellewellHellewell, 2002; Reference Ritsner, Ponizovsky and EndicottRitsner et al, 2002).

To date, no studies have examined the characteristics of second opinion referrals in psychiatry. We have reviewed the case notes of a series of patients referred for a second opinion to a single consultant over a 12-year period. This review gives an account of the purpose and outcome of these referrals. We believe that our experience may assist in clarifying the use of such referrals in National Health Service (NHS) practice.

Method

Clerical staff kept records in a manual database of all patients referred to a single out-patient clinic for a second opinion from 1988 until the retirement of the consultant (R.H.S.M.) in 2000. The consultant was a senior member of the academic staff at the University of Leeds and held an honorary consultant contract. At the time that the survey began in 1988 he had been in post for 11 years. The format of the second opinion service was, in essence, an out-patient clinic staffed by one consultant who had expertise in affective disorders, accompanied by one or more trainees. Secretarial support was also provided. No special multi-disciplinary service was offered. At the time that the survey began, The Leeds School of Medicine was the only medical school in the former Yorkshire Regional Health Authority.

We adopted the following definition of a second opinion referral for the purposes of the survey: a second opinion referral is a request for a clinical consultation made to a consultant psychiatrist when the patient is already under the care of a consultant psychiatrist. The definition of a second opinion that we employed was also satisfied if a patient had been referred to another psychiatrist for the same problem in the previous 2 years. The referral itself may be made from psychiatrist to psychiatrist or from general practitioner (GP) to the second opinion psychiatrist (provided that the patient was under the care of an existing psychiatrist) and may be initiated by the patient or by a third party such as a relative.

The case notes of all patients recorded in the manual database were reviewed and those that fulfilled our definition of a second opinion referral were included in the study. We excluded patients who were referred by medical specialists, non-medical health care workers and solicitors. All medical notes were identified, with no missing cases. Information was entered into a proforma, including personal details, the source of the referral, the nature of the problem leading to referral, the outcome of the consultation and any follow-up information that might be available. The assessors were two doctors (P.N., A.J.M.) who completed the proforma using the initial referral letter to obtain demographic data, the source of referral and the nature of the problem leading to the referral. The remainder of the information was obtained from the clinical notes. All the data were entered into a spreadsheet using Microsoft Excel and analysed using StatsDirect.

Results

Of the 103 case notes examined, 32 did not fulfil the inclusion criteria. The majority of the excluded notes were referrals from non-psychiatric sources (e.g. liaison referrals from physicians and surgeons) or patients who were not under sector psychiatrists. Of the remaining 71 patients, there were 34 (48%) women and 37 (52%) men. The mean age of subjects was 45.6 years (s.d.=13.8). Baseline diagnoses of patients (i.e. the original diagnosis at the point of referral) are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Diagnoses made prior to the referral

| Category | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Unipolar depression | 27 (38) |

| Organic condition | 9 (12.7) |

| Schizophrenia | 5 (7) |

| Biopolar affective disorder | 15 (21) |

| Personality disorders | 6 (8) |

| Anxiety disorders | 5 (7) |

| No diagnosis | 4 (5.6) |

A total of 38 (53%) patients were referred from the local catchment area (Leeds) and the remainder were referred from within the Yorkshire area. Of the 71 patients referred, 56% were from the patient's current psychiatrist and 44% were from the GP. In 10% of these cases the patient's family originally requested the referral, prior to it being made by the consultant or GP.

Reasons for referral

The most common reason for referral was treatment failure, followed by diagnostic difficulties (Table 2). Of all the referrals from parent consultants, none indicated the wish for the tertiary consultant to take over the case management of the patient.

Table 2. The main reasons for referral (categories not mutually exclusive)

| Reason for referral | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Failure to respond to treatment | 44 (62) |

| Diagnostic difficulties | 34 (48) |

| Patient request for consultant change | 20 (28) |

| Unexplained clinical deterioration | 13 (18) |

| Therapeutic breakdown | 18 (25) |

| Legal reasons | 2 (3) |

| Special treatments (including psychosurgery) | 3 (4) |

Outcome - change in diagnosis and treatment

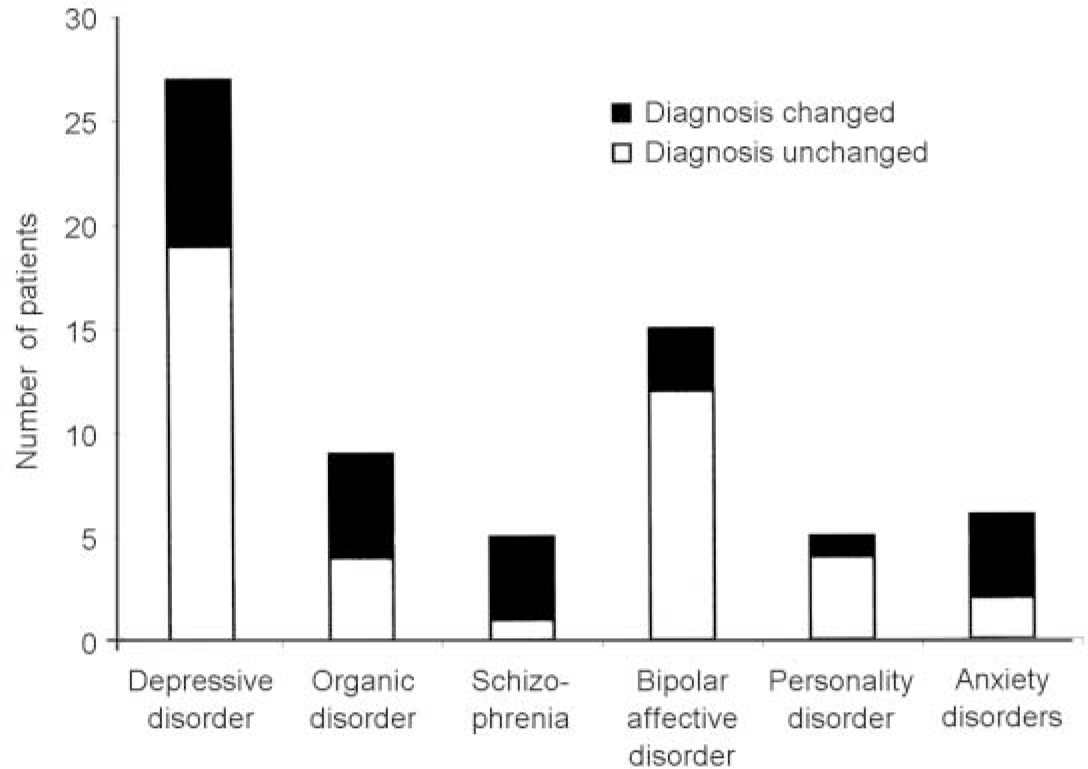

In the case of patients referred with unipolar depression, bipolar affective disorder and personality disorders, only a small proportion had an alternative diagnosis suggested. In contrast, for subjects with organic disorders, anxiety disorders and schizophrenia, diagnoses were changed after the majority of initial consultatations (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Change in diagnosis after initial second opinion assessment

In most cases alternative medication strategies were suggested (Table 3). Interestingly, this included a recommendation to be observed medication free in some cases. Unusual measures occasionally were suggested, such as requests for advice from a clinician in another medical speciality (mostly from neurology).

Table 3. Outcome after second opinion consultation

| Outcome | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Single consultation | 36 (50) |

| Two to four consultations | 9 (13) |

| Clinical responsibility assumed | 27 (38) |

| Admission | 7 (10) |

| Alternative diagnosis | 22 (31) |

| Alternative medication | 48 (68) |

| Electroconvulsive therapy | 6 (8) |

| Unusual measures | 6 (8) |

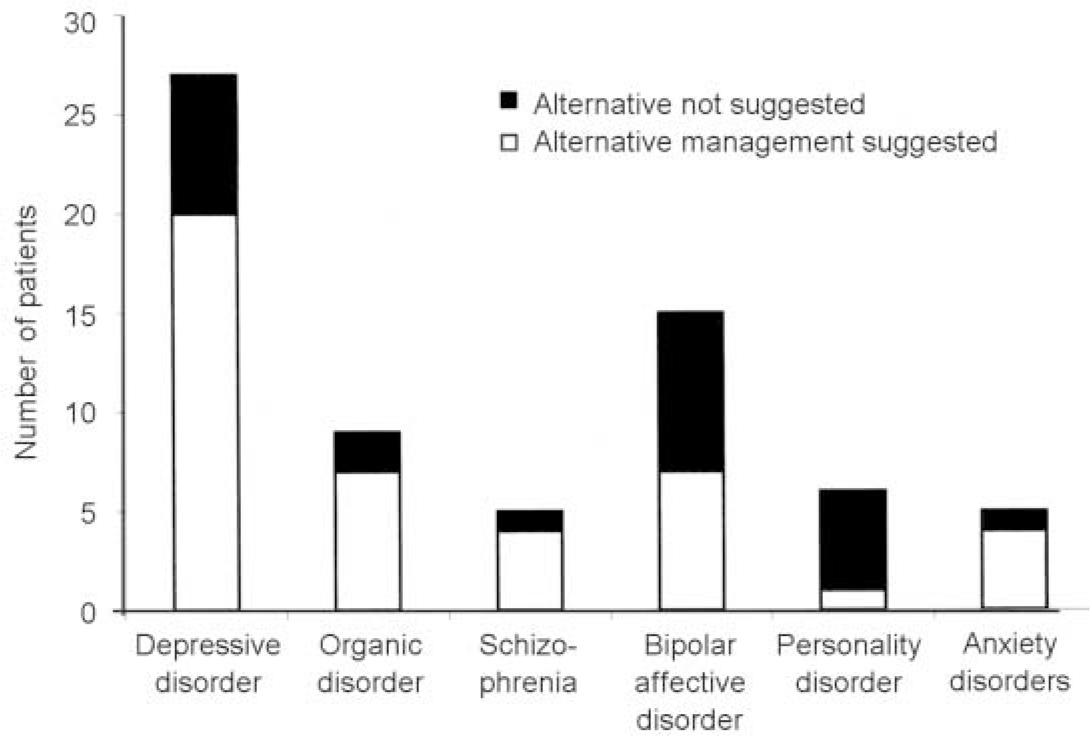

In terms of treatment changes by diagnosis, only one of the six referrals with personality disorder had alterations in management suggested, but in patients referred with bipolar affective disorder this was almost 50%. However, these were the exceptions because in the other diagnostic groups at least three-quarters had alterations in management suggested (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Suggestions for alternative management after initial consultation

Discussion

The likelihood of a referral for a second opinion is influenced by both patient-related and clinician-related variables. Sutherland & Verhoef (Reference Sutherland and Verhoef1989) examined the characteristics of patients seeking a medical second opinion from a university-based gastroenterology unit. Compared with patients seen after initial contact, patients seen after a second opinion not only had more chronic illness, but also had an external locus of control - a finding compatible with seeking answers to continuing medical complaints. Surprisingly, no published studies have examined predictors of second opinion referrals within a general psychiatric setting.

In terms of diagnoses, unipolar depressive disorder and bipolar affective disorder were the most common disorders at the point of referral. The most common final diagnosis was mood disorder, which is in part a reflection of the high baseline rate of mood disorder referred to the clinic. Furthermore, both the baseline and outcome diagnoses reflected the local special expertise of the consultant concerned, because many cases would have been initiated with the knowledge that special advice in the field of mood disorder was available even though this was not a specific mood disorders service.

The most common reasons for a second opinion request were treatment failure followed by diagnostic uncertainty. The frequency with which alternative diagnoses were suggested (31%) and different approaches to management were recommended (68%) strongly suggests that the request for second opinions in psychiatric practice carries possible benefits for patients. By examining each patient group individually, alternative management strategies were suggested in most patients with depressive disorder, organic psychiatric disorder, schizophrenia and anxiety disorder. In fact, only in the category of personality disorder was alternative management rarely suggested. This reinforces an important message to clinicians and carers, that alternatives are often available even when patients appear to have treatment-resistant or unusual disorders. In some cases, this meant resorting to unusual measures, such as referral for psychosurgery, and in others a period of medication-free observation was suggested. We believe that, given the large number of management options, there is little justification for therapeutic nihilism in most common conditions.

In the majority of cases, the original diagnosis was not changed. In these cases reassurance about the diagnosis provides support for the approach adopted by the referring doctor and their colleagues, and also confirmation for the patient and their families. For a significant proportion (38%) clinical responsibility was assumed by the tertiary consultant for the patient. In some cases this occurred because the patients were admitted for a review of the diagnosis, for a trial of an alternative treatment or for other reasons. In a minority of cases the referring consultant requested the second opinion consultant to take over clinical responsibility for that patient after the initial referral. This finding is particularly relevant to the catchment area services, where the alternatives to care by the catchment area team are limited and require referral to a team without an exclusive commitment to a particular geographical area. Thus, trusts should consider the need for such a ‘safety valve’. Our study could not assess the number of patients suitable for referral who were not referred. We have observed considerable reluctance from some colleagues to use any second opinion service and this must be reflected in the quality of care for patients with particularly refractory illnesses. Several surveys have shown that there is a substantial unmet need for patients with difficult-to-treat illnesses who are maintained on psychotropic medication despite significant symptoms and/or adverse effects (Reference Naber and KasperNaber & Kasper, 2000; Reference HellewellHellewell, 2002). The impact of a second opinion system on this problem deserves further study.

Half of all cases only attended the clinic on one occasion and a further 13% attended between two and four times. It seems evident that the purpose of the referral was achieved by one visit in a substantial proportion of the patients. In most cases this took the form of some kind of advice to colleagues. Without such a second opinion service, many psychiatrists may be unsure from whom to seek help in difficult cases.

This survey provides some initial data on the use of a second opinion service in West Yorkshire. However, we acknowledge some limitations of this survey. The consultant running the clinic had a special interest in mood disorders and this is likely to have influenced the type of patients referred. Secondly, data were collected naturalistically, therefore we could not examine variables such as illness severity or specific treatment responses. In addition, it was not possible to assess satisfaction or clinical outcomes, but this could be a topic for further work. In other disciplines a number of studies (Reference McSherry, Chen and WornerMcSherry et al, 1997; Reference Kronz, Westra and EpsteinKronz et al,1999; Reference Hahm, Niemann and LucasHahm et al, 2001) have suggested that second opinions cannot only result in therapeutic and prognostic modifications, but also prove to have an improved cost-saving benefit to the NHS. In our service, certain markers of success were evident during the period that the clinic was operational. For example, the service improved (rather than interfered with) therapeutic relationships between consultant psychiatrists, and patients and relatives, by addressing their concerns. In some cases, conflicts of opinion within the referring team were arbitrated. In other situations, it allowed for a change of consultant in the least disruptive way.

In conclusion, there appears to be a place for second opinions in psychiatric practice. Our data show that different approaches to diagnosis and treatment were recommended in the majority of referrals. In our experience second opinions can bring about increased confidence in diagnosis and patient management, enhance doctor-patient relationships and improve working relationships with colleagues. Improvements in clinical outcomes require further examination. We recommend that such a service be made available generally within the NHS psychiatric services. Second opinions should be regarded as routine practice in cases of diagnostic and therapeutic difficulty. The purposes of the referral should be considered carefully by the referring agencies in terms of their expectations and requirements. In its best form, the patient and their relatives become actively involved in the procedure. Certainly there is an educational value for the referring team, especially for the junior medical staff and indeed for the tertiary team itself.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Mrs Sylvia Place and Mrs Jean Davison, clinic secretaries, who collected much of the data for this survey.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.