The right–left ideological dimension is a fundamental feature of politics in many nations around the world.Footnote 1 This article examines the relationship between two preference dimensions that are widely recognized as central to ideological differences between the right and left: the economic dimension, which concerns redistributive social welfare preferences and views about the proper scope of government economic involvement, and the cultural dimension, which concerns views on matters such as sexual morality and immigration.Footnote 2

Within mass publics around the world, do people who hold right-wing cultural attitudes also tend to adopt right-wing economic attitudes? Do left-wing cultural attitudes typically go with left-wing economic attitudes? The established view from political science is that there do not exist psychological constraints that would make this the case for most of the people most of the time.Footnote 3 In contrast, an influential research tradition within psychology specifies that cultural and economic conservatism have common psychological origins and thus typically co-occur.Footnote 4 Despite its theoretical importance and potential implications for quality of democratic representation, the typical association between cultural and economic attitudes within mass publics around the world has not been firmly empirically established.

In this article we report what is to our knowledge the largest cross-national test to date of this empirical relationship, using World Values Survey (WVS) data from 229 national samples spanning ninety-nine nations. We furthermore examine how the alignment of these two dimensions varies across people and contexts. Our findings suggest that: (1) it is not typical for cultural and economic attitudes to be aligned on the right–left dimension, (2) it is more common for right-wing cultural views to be coupled with left-wing economic views (and vice versa) – an attitude organization that reflects a contrast between desires for cultural and economic protection vs. freedom Footnote 5 (3) protection–freedom attitude organization typically outweighs right–left attitude organization within post-communist nations, within socially traditional and low-development nations, and among low-political-engagement individuals and (4) data are consistent with key background characteristics – specifically, social class and needs for security and certainty – exerting opposite right–left ideological influences across the cultural and economic domains, potentially underlying protection–freedom attitude organization. We propose that the right–left dimension promoted in much political discourse operates in a state of tension with a demographically and psychologically based protection vs. freedom attitude organization, and we explore the implications of this possibility for the psychological bases of ideology, quality of democratic representation and the rise of extreme right politics in the West.

THE POSSIBILITY OF PSYCHOLOGICALLY CONSTRAINED RIGHT–LEFT ATTITUDE ORGANIZATION

Converse famously proposed that most people do not form political attitudes on the basis of ideological reasoning.Footnote 6 One component of this argument centered on findings involving ‘constraint’, defined as functional interdependence among distinct political attitudes. Within American samples from the 1950s, right-wing vs. left-wing position on one political attitude usually did not predict right-wing vs. left-wing positions on other political attitudes. Converse concluded that there existed little in the way of psychological sources of ideological constraint – that is, psychological mechanisms that lead people to hold either consistently left-wing or right-wing stances across a range of issues.

Political scientists have generally accepted this aspect of Converse’s account.Footnote 7 Although politically engaged Americans do align their political attitudes on the right–left dimension,Footnote 8 and although their tendency to do so has increased in recent decades,Footnote 9 political scientists generally agree that ideological constraint among politically attentive citizens results from such citizens following elite political cues. Specifically, political elites tend to package diverse issue positions into ideological bundles in order to attract broad coalitions.Footnote 10 The resulting attitude structure is conveyed in political messages through the news media and informal political commentary. Thus, according to this view, there is no natural reason why being left-wing (right-wing) on cultural matters should necessarily go with being left-wing (right-wing) on economic matters. To the extent that people do organize their attitudes along the right–left dimension, this is because of discourse involving partisan and ideological cues.Footnote 11 Low levels of exposure to such discourse should be associated with a weaker positive association, or no association at all, between conservative cultural and economic attitudes.

In contrast, a long tradition of research within political psychology has posited that there are key psychological sources of ideological constraint on the right–left dimension. According to these perspectives, which are collectively dubbed the ‘Rigidity of the Right’ model, cultural and economic conservatism have similar origins in a set of related psychological attributes. This view can be traced to the guiding hypothesis of Adorno et al. that ‘the political, economic, and social convictions of an individual often form a broad and coherent pattern … and that this pattern is an expression of deep-lying trends in his personality’.Footnote 12 Five decades later, Jost et al. integrated various arguments along these lines, distilling as their common essence the premise that both cultural and economic forms of conservatism are similarly rooted in underlying needs to reduce uncertainty and manage threat (hereafter, ‘needs for security and certainty’Footnote 13 ).Footnote 14 According to these views, cultural and economic conservatism tend to go together for most people most of the time because needs for security and certainty attract individuals to a worldview that both maintains traditional modes of conduct (cultural conservatism) and resists destabilization of the prevailing economic hierarchy (economic conservatism).Footnote 15 Viewpoints along these lines underlie much contemporary scholarship on the psychological origins of political attitudes, and are reflected in the common practice of testing a single right–left ideological dimension as a correlate of psychological or biological characteristics.Footnote 16

However, some have proposed that cultural and economic attitudes arise from distinct sources, and that the psychological origins of these attitudes are context dependent.Footnote 17 In a recent review, Hibbing, Smith and Alford noted that many of the characteristics presumed to underlie a generalized conservatism might be ‘less relevant to economic issues such as free market principles, tax codes, and the size of government than they are to social issues such as matters of reproduction, relations with out-groups, suitable punishment for in-group miscreants, and traditional/innovative lifestyles’,Footnote 18 and that ‘historical and cultural context plays an important role in these relationships’.Footnote 19 Indeed, evidence suggests that while needs for security and certainty reliably predict cultural conservatism, they do not reliably predict economic conservatism,Footnote 20 and that relations with the latter might vary across cultural contexts.Footnote 21 These considerations suggest that the dispositional origins of political attitudes in needs for security and certainty might not favor right–left attitude organization all, or even most, of the time.

THE POSSIBILITY OF PROTECTION–FREEDOM ATTITUDE ORGANIZATION

A recent set of viewpoints has extended this line of thinking, and provides a basis for predicting that an attitude organization that contrasts desires for cultural and economic protection vs. freedom might outweigh right–left attitude organization when one considers a broad array of people from around the world.Footnote 22 According to these views, needs for security and certainty will sometimes – and perhaps often – promote opposite right–left ideological stances across the cultural and economic domains. On the one hand, needs for security and certainty attract people to right-wing cultural policies, for the sense of security, order and stability – or cultural protection – that these policies provide.Footnote 23 On the other hand, this match between needs for security and certainty and the desire for protection often has different implications for economic attitudes. Absent other influences, those who prioritize security and certainty might desire the material protection and stability that left-wing economic policies aim to provideFootnote 24 – that is, they might prefer left-wing economic policy for instrumental reasons.Footnote 25 If this is the case, then needs for security and certainty would promote protection–freedom attitude organization. Those high in needs for security and certainty would desire the cultural protection of traditional norms and the economic protection of interventionist policy, whereas those low in needs for security and certainty would favor the cultural freedom of progressive policy and the economic freedom of a less restrictive and redistributive policy.Footnote 26 Moreover, decades of survey research reveal that low social class (another factor that would lead people to seek protection) is associated with left-wing economic attitudes but right-wing cultural attitudes.Footnote 27 This might further bolster protection–freedom attitude organization.

These viewpoints, do not, however, suggest that protection–freedom attitude organization will prevail over right–left attitude organization within all contexts. In particular, some people are exposed to a high volume of political discourse indicating that right-wing cultural and economic attitudes go together in a right-wing or conservative package, while left-wing cultural and economic attitudes go together within a left-wing or liberal package. Exposure to such discourse promoting right–left attitude organization should lead people who are high in needs for security and certainty to favor right-wing economic views, because such views are symbolically consistent with their right-wing cultural views.Footnote 28 This is what Johnston et al. refer to as an expressive influence:Footnote 29 politically engaged people who have strong needs for security and certainty adopt right-wing economic positions to bolster a culturally based conservative identity.Footnote 30 Thus while these views suggest that protection–freedom attitude organization will often prevail, strong exposure to messages promoting right–left attitude organization might counteract this tendency.

THE EMPIRICAL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CULTURAL AND ECONOMIC CONSERVATISM

What does prior research suggest about the typical relationship between cultural and economic conservatism? It is quite clear that the right–left dimension is useful for characterizing elite policy differences in many countries: cultural traditionalism and free-market economic views are associated with the right, while cultural liberalism and redistributive economic views are associated with the left.Footnote 31 Also, within the American general public, traditional cultural attitudes typically correlate positively with free-market economic attitudes.Footnote 32 Moreover, right-wing authoritarianism (sometimes likened to cultural conservatism) often (though not always) correlates positively with social dominance orientation (sometimes likened to economic conservatism) in psychological studies of convenience samples.Footnote 33 Despite these findings, however, a number of considerations suggest that one should not at this point infer a globally widespread functional congruence between right-wing (or left-wing) positions on the cultural and economic dimensions.

The first consideration is that most of this research has been conducted in either the United States or other developed and democratic Western nations. As we discuss below, there is reason to expect differences in attitude structure as a function of development and related cultural characteristics. Secondly, the degree to which culturally and economically conservative attitudes are structured together on the right–left dimension has increased over time in the United States, as the context of political discourse has changed,Footnote 34 again suggesting contextual variability in the prevailing attitude structure. Thirdly, even within the United States, right-wing cultural and economic attitudes tend to correlate positively only among people with relatively strong exposure to political discourse, such as political elites or politically engaged members of the general public.Footnote 35 This further attests to the role of discursive context in this relationship. Fourthly, a right–left structuring of cultural and economic attitudes often does not characterize political competition in post-communist European nations.Footnote 36 Fifthly, evidence from Western European mass publics indicates a notable prevalence of ‘left authoritarians’ who espouse culturally right-wing but economically left-wing views.Footnote 37 And, finally, intercorrelations between right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation measures should not be taken as evidence of association between cultural and economic attitudes. Although right-wing authoritarianism measures reflect cultural traditionalism (with a particular focus on aggressive and paranoid content),Footnote 38 social dominance orientation measures clearly subsume both cultural (for example, aggressive ethnic dominance) and economic (for example, reduction of income inequality) content.Footnote 39 All of this suggests caution in inferring functional congruence between right-wing vs. left-wing positions in the cultural and economic domains based on existing findings.

In sum, when one takes seriously measurement and sampling issues, the typical relationship between right-wing cultural and economic attitudes within mass publics throughout the world is not clear. Therefore, the first goal of the present research is to examine the typical relationship between cultural and economic attitudes within mass publics around the world.

MODERATORS OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CULTURAL AND ECONOMIC CONSERVATISM

In this section we discuss potential sources of variability in the relationship between cultural and economic attitudes across people and contexts. We draw on theory and research from two areas: (1) the role of political engagement in political attitude structuring and (2) cross-national differences in institutions, development and modernization.

The Role of Political Engagement

Political scientists have long argued that the relationship between cultural and economic attitudes is conditional on a person’s level of political engagement.Footnote 40 Because elite political competition often occurs along the right–left dimension, news media messages about politics often describe political matters in right–left ideological terms, indicating which issue stances and values are associated with the right and which are associated with the left. As a consequence of exposure to partisan and ideological cues, politically engaged people display this type of attitude organization.

Consistent with this account, Americans who are highly politically engaged are the ones most likely to organize their cultural and economic attitudes along the right–left dimension; those low in political engagement are more likely to adopt a ‘mixed bag’ of attitudes.Footnote 41 But to our knowledge, no previous study has provided a large-scale crossnational test of the role of political engagement in the structuring of cultural and economic attitudes. Indeed, the degree to which politically engaged people structure their attitudes on the right–left dimension might depend on the characteristics of the nation in which they reside.

Cross-National Variation

In what kinds of nations will citizens, and politically engaged citizens in particular, structure their cultural and economic attitudes on the right–left dimension? In what types of nations will protection–freedom attitude organization be more common? We consider post-communist status as well as economic development and modernization as potential sources of cross-national variation.

Post-communist status

Evidence suggests that within societies that were under communist rule during the Cold War, characteristics pertaining to needs for security and certainty are linked to left-leaning preferences concerning economic equality.Footnote 42 This might be because the historically dominant ideology centered around economic egalitarianism, and those who prize order and stability most highly might gravitate toward this familiar economic leaning. Because such individuals should also favor cultural conservatism,Footnote 43 protection–freedom attitude organization might be especially common in post-communist nations.

Development and modernization

Modernization theory, in its various formulations, focuses on the relationships between cultural, economic and political changes within societies.Footnote 44 Although some important claims made by modernization theorists are controversial, it is clear that economic development within societies has tended to coincide with cultural changes involving an easing of traditional sexual morality constraints.Footnote 45 We propose that indicators of modernization – particularly, human development and declines in sexual morality traditionalism – are relevant to how politically engaged citizens organize their cultural and economic attitudes.

First of all, citizens of developed nations are, by definition, more educated and more likely to have the time and resources to expose themselves to a range of political information. This raises the possibility that citizens of developed nations who are engaged with politics would be the most likely to understand the historical and philosophical role of the right–left dimension in structuring political competition. To be sure, the right–left dimension does not have the exact same meaning in all developed nations, but it tends to be used in a fairly consistent way to describe broad postures in the economic and cultural domains.Footnote 46 Furthermore, to the extent that citizens of developed nations are more likely to adopt attitudes for self-expressive reasons,Footnote 47 those who are politically engaged within developed nations might be especially motivated to adopt a package of cultural and economic attitudes that is consistent with a coherent right- or left-wing identity.

A second reason why modernization might affect political attitude structuring relates to the distribution of sexual morality preferences within a society. Structural indicators of modernization (such as human development) coincide with movement away from traditional lifestyle and sexual morality views among substantial segments of the population.Footnote 48 This reflects a process whereby traditional social constraints on the proper mode of conduct are weakened and many people feel greater freedom to explore other ways of living. But not all individuals are equally comfortable with this weakening of traditional cultural norms. Thus within relatively progressive societies, there is a divide between individuals who continue to maintain traditional cultural views and those who are culturally progressive.Footnote 49 This social divide, when combined with enhanced self-expressive values and education, can become an important component of political identity. Moreover, it can lead politically engaged people to adopt preferences in the economic domain that they have been informed are consistent with their culturally based political identities. Referring to the American context, Johnston et al. described this cleavage as reflecting ‘cultural and lifestyle politics’, and argued that it has ‘reshaped the bases of economic preferences among politically engaged citizens, such that they are best understood as expressively-motivated signals of personality and identity, rather than instrumentally-motivated beliefs about what policies will bring about optimal outcomes’.Footnote 50

A similar phenomenon may occur when cultural and lifestyle cleavages become politically salient in other nations where traditional norms have weakened. In many such nations, political elites and parties of the economic right have tended to strategically appeal to cultural traditionalists under a broad right-leaning ideological banner, tying right-wing economic views to negativity toward progressive societal changes, while elites and parties of the economic left have appealed to cultural progressives under a broad left-leaning banner.Footnote 51 This raises the possibility that politically engaged people within societies where traditional lifestyle norms have weakened are especially likely to receive messages that cultural and economic views should be organized together on the right–left dimension, and that they will align their attitudes correspondingly.

THE PRESENT RESEARCH

The present research has two main goals. The first is to provide a large-scale cross-national test of the typical relationship between cultural and economic attitudes within nations around the world. The second goal is to examine cross-national and individual-level variation in the degree to which right-wing (vs. left-wing) cultural and economic attitudes tend to go together. In addition to these primary goals, we also further examine the possibility that social class and needs for security and certainty are sources of protection–freedom vs. right–left attitude organization.Footnote 52

METHOD

The data from this study come from the WVS, which has fielded hundreds of national surveys in nations around the world over six assessment waves since the early 1980s. Of these nation-year samples, 229 were administered sufficient measures (meaning at least one cultural attitude measure and at least one economic attitude measure) for inclusion in at least one of the present analyses. These national samples were surveyed between 1989 and 2014.Footnote 53

Nation-Year Samples and Participants

The 229 nation-year samples and their sizes are listed in the first two columns of Appendix A. A total of ninety-nine nations that have at least one sample are included in this table. These include the types of highly developed Western nations typically studied in political attitudes research, as well as medium- and low-development nations. All habitable continents are represented, and the nations as a whole vary greatly in terms of development, political institutions and culture. Furthermore, each of the world’s ten most populous nations was represented with at least two samples.

Nation-year samples varied in size from 240 (Montenegro, 1996) to 3,531 (South Africa, 2013) with a mean of 1,422.72 (SD=551.49). The total sample size across all usable nation-year samples was 325,802. Across all samples, 51.7 per cent of respondents were female, 48.2 per cent were male and 0.1 per cent did not indicate their sex. Ages ranged from fifteen to ninety-nine years with a mean of 40.85 (SD=16.13).

Measures

All variables were initially coded to range from 0 to 1. Cultural and economic political attitudes were coded so that a higher score corresponds with right-wing opinion and a lower score corresponds with left-wing opinion. Nation-year sample means for the main WVS measures are displayed in Columns 3 through 9 of Appendix A, and question wording and additional measurement information are presented in Appendix B.

Right-wing vs. left-wing cultural attitudes

Three cultural attitude indicators were used in the present analyses: sexual morality (a composite of abortion and homosexuality attitudes; mean within-nation-year sample r=0.41 [SD=0.15]), immigration (single item) and women’s role in the workforce (single item).

Right-wing vs. left-wing economic attitudes

Two economic attitude indicators were used in the present analyses: social welfare (a composite of attitude regarding income inequality and attitude about government responsibility for providing for people; mean within-nation-year sample r=0.22 [SD=0.14]) and preference for private vs. government ownership of business and industry (single item).

Political engagement

We computed a political engagement measure as a composite of two indicators that were widely available across the national samples: importance of politics in one’s life and political interest (mean within-nation-year sample r=0.53 [SD=0.12]).

Needs for security and certainty

Needs for security and certainty was measured as a composite of five items from a short version of the Schwartz value survey,Footnote 54 which was administered to respondents in Waves 5 (2005–07) and 6 (2010–14) only. These items represent five values that fall along the conservation vs. openness to change axis in the Schwartz value circumplex: tradition, security, conformity, self-direction (reverse scored) and stimulation (reverse scored).Footnote 55 Item responses were centered around their within-person mean importance ratings (across all ten value items) before being reverse scored (where appropriate) and averaged into a composite (mean within-nation-year sample Cronbach’s alpha=0.51 [SD=0.12]).

Demographic control variables

Sex, age, education and household income decile were used as control variables.

Nation-level variables

Post-communist status, human development (United Nations Human Development Index) and national traditionalism (mean levels of sexual morality conservatism across all of a nation’s surveys) were recorded as nation-level variables.

RESULTS

Do Right-Wing Cultural Attitudes Tend to Go with Right-Wing Economic Attitudes?

Within-nation zero-order correlations

The first question of interest is whether the within-nation associations between right-wing cultural and economic attitudes are more often positive or negative. We initially addressed this question by computing bivariate correlation coefficients for each cultural-economic attitude pair within each nation for which both variables were available, collapsing across the relevant nation-year samples. If right-wing cultural and economic attitudes typically go together, then one would expect more positive than negative correlations.

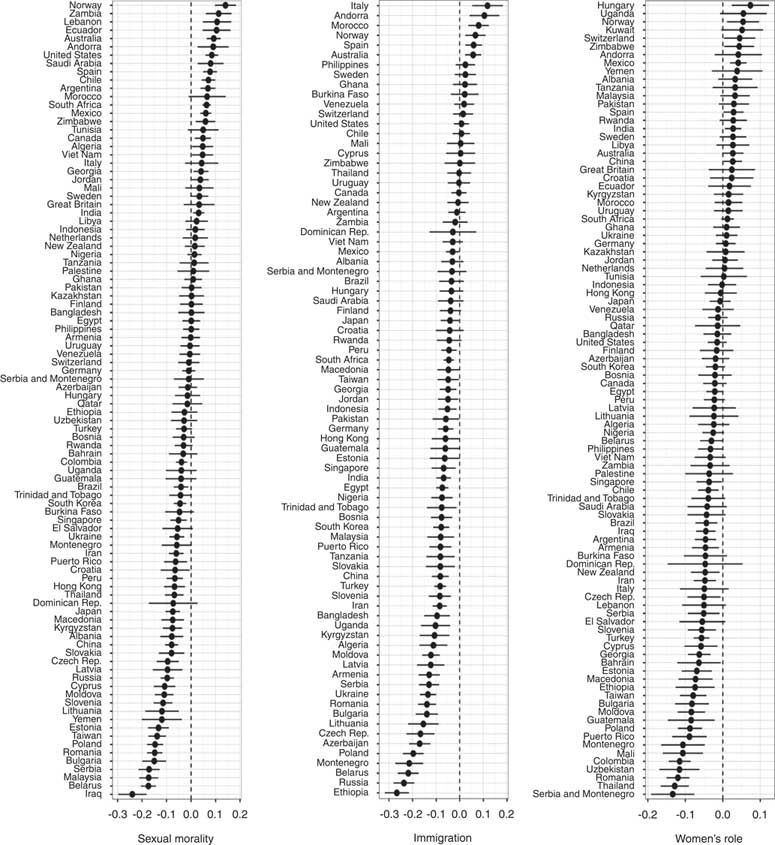

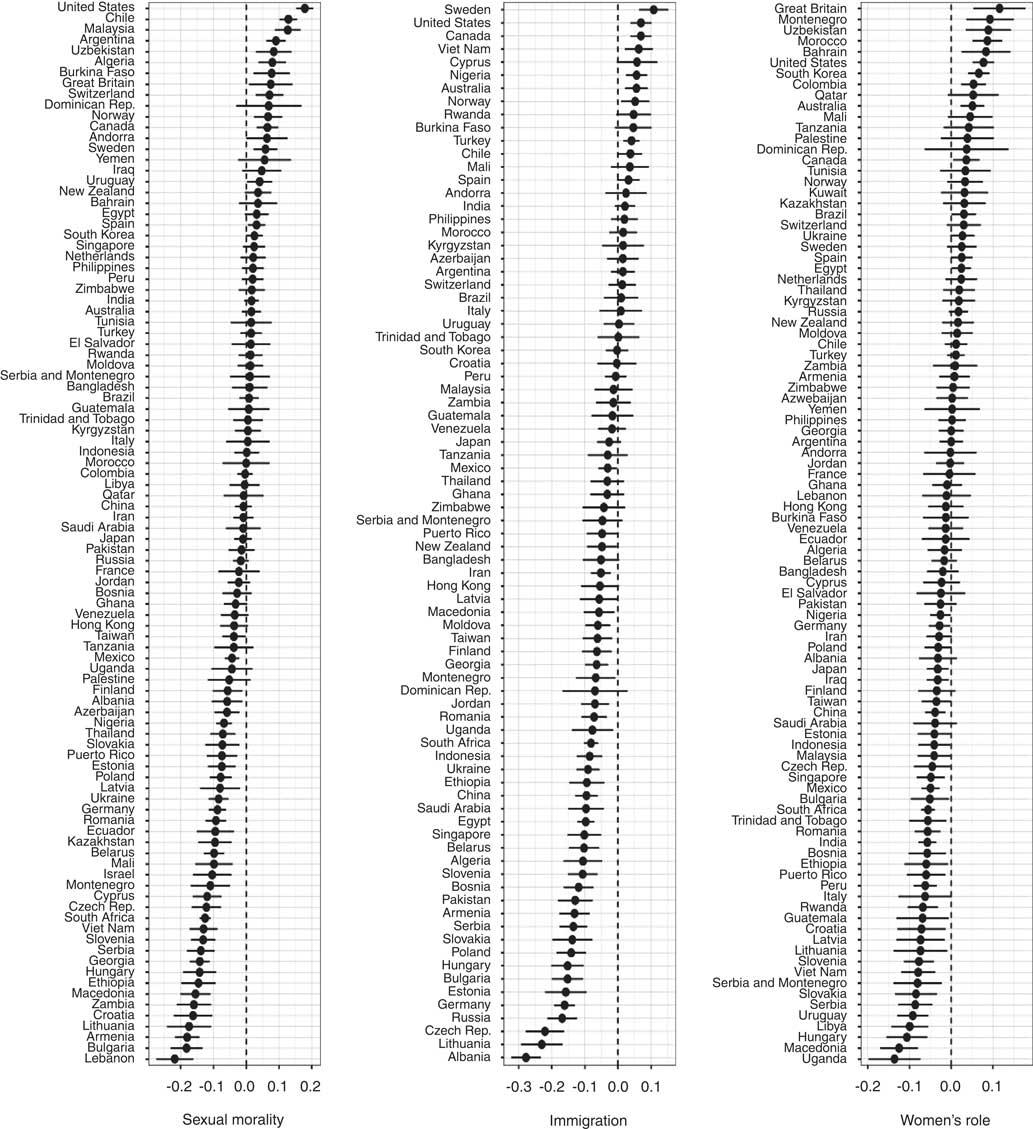

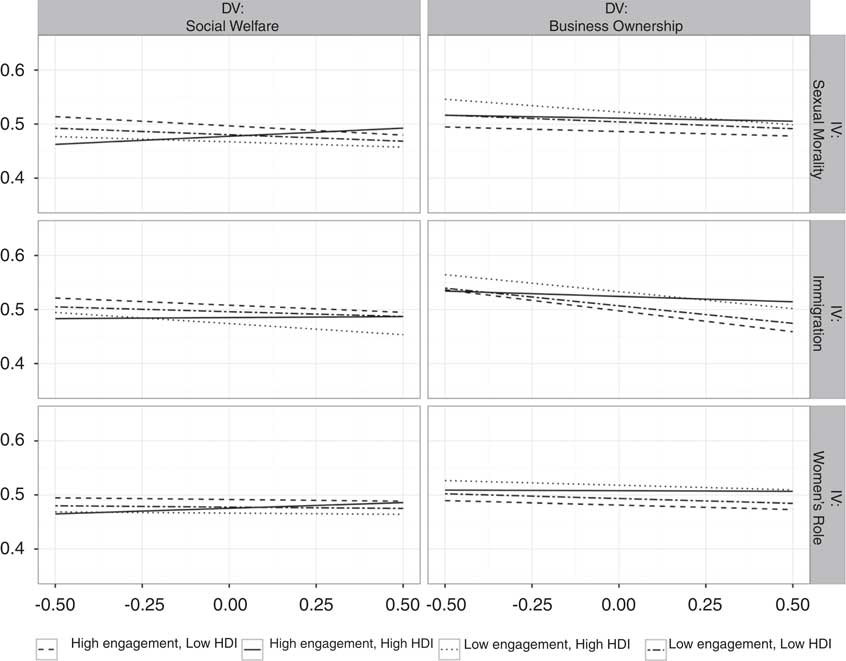

Table 1 summarizes the results of these analyses, and Figures 1 and 2 display the withinnation correlations and their 95 per cent confidence intervals. Figure 1 displays correlations with social welfare conservatism as the economic variable and Figure 2 displays correlations with business ownership conservatism as the economic variable. Each figure is divided into three panels, one for each of the cultural conservatism variables.

Fig. 1 Within-nation correlations between social welfare conservatism and three cultural conservatism variables

Fig. 2 Within-nation correlations between business ownership conservatism and three cultural conservatism variables

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics for Within-Nation Correlations between Culturally and Economically Right-Wing Attitudes

Note: means and standard deviations computed with Fisher transformations. Significant correlations are those with two-tailed p-values≤0.05.

As displayed in Table 1, for each of the six pairs of cultural and economic attitudes, the mean within-nation correlation was small and negative. As displayed in Figures 1 and 2, for each of these pairs, negative correlations with 95 per cent confidence intervals that do not include zero greatly outnumber positive correlations with 95 per cent confidence intervals that do not include zero. The percentage of nations for which the correlation was significantly positive (suggesting that right-wing cultural and economic attitudes more often go together) ranged from 7.4 per cent (Immigration-Business Ownership) to 20.8 per cent (Sexual Morality-Business Ownership) (see Table 1).Footnote 56 Meanwhile, the percentage of nations for which the correlation was significantly negative (suggesting that right-wing cultural views more often go with left-wing economic views) ranged from 34.0 per cent (Women’s Role-Business Ownership) to 58.0 per cent (Immigration-Business Ownership).Footnote 57

These initial analyses suggest that the organization of cultural and economic attitudes along the right–left dimension is not typical within nations around the world. In fact, there were substantially more nations in which cultural and economic conservatism were negatively correlated.

Random coefficient regression analyses

We next examined the typical association between cultural and economic attitudes in a way that accounts for the nested data structure and controls for basic demographics. Specifically, we ran a series of three-level random coefficient regression analyses with respondents nested within years (that is, individual surveys conducted in a specific year in a specific nation) nested within nations.Footnote 58 In all analyses, individual-level predictor variables were centered around nation-year means. Parameters were estimated with restricted maximum likelihood.

In each analysis an economic conservatism variable (social welfare or business ownership conservatism) served as the dependent variable and a cultural conservatism variable (sexual morality, immigration or women’s role) was entered as a level-1 predictor along with the demographic control variables (sex, age, education and household income). The intercept and the slope for the cultural conservatism variable were permitted to vary across years within nations as well as across nations.Footnote 59 The formal model is displayed at the beginning of Appendix E. Of primary interest is the fixed effect of culturally conservative attitude on economically conservative attitude (γ 100 in the formal model). This represents the pooled regression slope for cultural conservatism across all surveys and nations.

The results of analyses with social welfare conservatism as the dependent variable are presented in Appendix Table E1. In the model with sexual morality conservatism as the predictor, the cultural-economic attitude relationship was near zero, and its 95 per cent confidence interval included zero (γ=−0.009, SE=0.008, 95 per cent CI [−0.024, 0.006]). When this analysis was repeated substituting immigration attitude for sexual morality conservatism, right-wing immigration attitude was negatively related to right-wing social welfare attitude, and its 95 per cent confidence interval did not include zero (γ=−0.022, SE=0.008, 95 per cent CI [−0.037, −0.006]). And when women’s role attitude was entered as the cultural attitude variable, its coefficient was near zero with a 95 per cent confidence interval that included zero (γ=0.001, SE=0.003, 95 per cent CI [−0.005, 0.007]).

The above three analyses were repeated with business ownership attitude as the dependent variable, and the results of these analyses are displayed in Appendix Table E2. In these analyses, all three right-wing cultural attitudes were negative predictors of rightwing business ownership attitude with 95 per cent confidence intervals that did not include zero (sexual morality conservatism: γ=−0.024, SE=0.010, 95 per cent CI [−0.043, −0.005]; immigration conservatism: γ=−0.057, SE=0.009, 95 per cent CI [−0.075, −0.039]; women’s role conservatism: γ=−0.015, SE=0.003, 95 per cent CI [−0.022, −0.008]).

Next, each of the above analyses examining a cultural attitude as a predictor of an economic attitude was repeated but with the economic attitude as a predictor and the cultural attitude as the outcome variable. This was done because the economic and cultural attitudes differed in their variances and their patterns of correlations with the control variables, raising the possibility that swapping their positions in the analyses would lead to a different pattern of findings. Social welfare conservatism did not significantly predict sexual morality conservatism (γ=−0.001, SE=0.007, 95 per cent CI [−0.015, 0.013]) or women’s role conservatism (γ=−0.002, SE=0.007, 95 per cent CI [−0.016, 0.011]), but did negatively predict immigration conservatism (γ=−0.032, SE=0.009, 95 per cent CI [−0.050, −0.014]). Ownership conservatism did not predict sexual morality conservatism (γ=−0.008, SE=0.005, 95 per cent CI [−0.019, 0.002]), but did negatively predict immigration conservatism (γ=−0.044, SE=0.007, 95 per cent CI [−0.057, −0.031]) and women’s role conservatism (γ=−0.028, SE=0.006, 95 per cent CI [−0.040, −0.016]).

Consistent with the bivariate correlations reported above, no evidence suggested that there are typically positive relationships between right-wing cultural and economic attitudes within mass publics around the world. Rather, there were several small but negative pooled relationships between right-wing cultural and economic attitudes.

Where Do Right-Wing Cultural Attitudes Tend to Go with Right-Wing Economic Attitudes?

We next tested hypotheses regarding cross-national variation in (1) the relationship between cultural and economic conservatism and (2) the degree to which political engagement moderates this relationship.Footnote 60 We analyzed three nation-level variables: post-communist status, development and national traditionalism. To examine each nation-level variable as a moderator of the associations between cultural and economic conservatism, we added to the initial models the nation-level variable (grand mean centered) and the cross-level interaction between the nation-level variable (grand mean centered) and cultural conservatism (centered around nation-year mean). The formal model is displayed at the beginning of Appendix F. Of primary interest is γ 101, which is the coefficient for the cross-level interaction between the nation-level variable and the cultural conservatism variable. Appendix Tables F1–F6 display the results of these analyses.

To examine whether political engagement moderates the association between cultural and economic conservatism to different degrees across different kinds of nations, we tested the three-way interactions between each nation-level variable (grand mean centered), political engagement (nation-year mean centered) and cultural conservatism (nation-year mean centered) in a model including all three of these predictors and the two-way interactions among them, as well as the demographic controls. The formal model is displayed at the beginning of Section G of the Appendix. Of primary interest is γ 301, which is the coefficient for the three-way interaction between political engagement, the cultural conservatism variable and the nation-level variable. Appendix Tables G1–G6 display the results of these analyses.

Post-communist status

Within nations that were under communist domination during the Cold War, the traditional value-based underpinnings of social conservatism might give rise to left-wing economic views.Footnote 61 Indeed, the analyses testing the two-way interactions revealed that post-communist status significantly moderated all six relationships between cultural and economic conservatism variables (see Appendix Tables F1 and F2). In each case, the interaction term’s coefficient was negative, indicating that the cultural-economic conservatism relationship was more negative in post-communist nations than it was in other nations.

As displayed in Table 2, cultural-economic conservatism correlations were far more likely to be negative within post-communist nations than within non-post-communist nations. For all six cultural-economic attitude pairs, correlations were significantly negative in the majority of post-communist nations (ranging from 51.9 to 84.0 per cent) and were rarely significantly positive (0.0 to 7.4 per cent). Within non-post-communist nations, correlations were significantly positive between 10.0 and 27.5 per cent of the time, but were significantly negative 22.5 to 46.4 per cent of the time. Within these nations, significant negative correlations were a good deal more frequent than significantly positive correlations for four of six cultural-economic attitude pairs (those involving immigration or women’s role as the cultural variable). Meanwhile, the three-way interactions between post-communist status, political engagement and cultural conservatism were significant in only two out of six analyses, such that differences between post-communist and non-post-communist nations in two of the cultural-economic associations were accentuated among high political engagement citizens (see Appendix Tables G1 and G2).

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics for Within-Nation Correlations between Culturally and Economically Right-Wing Attitudes Within Post-Communist and All Other Nations

Note: means and standard deviations computed with Fisher transformations. Significant correlations are those with two-tailed p-values ≤0.05. Post-com=post-communist nations.

UNHDI

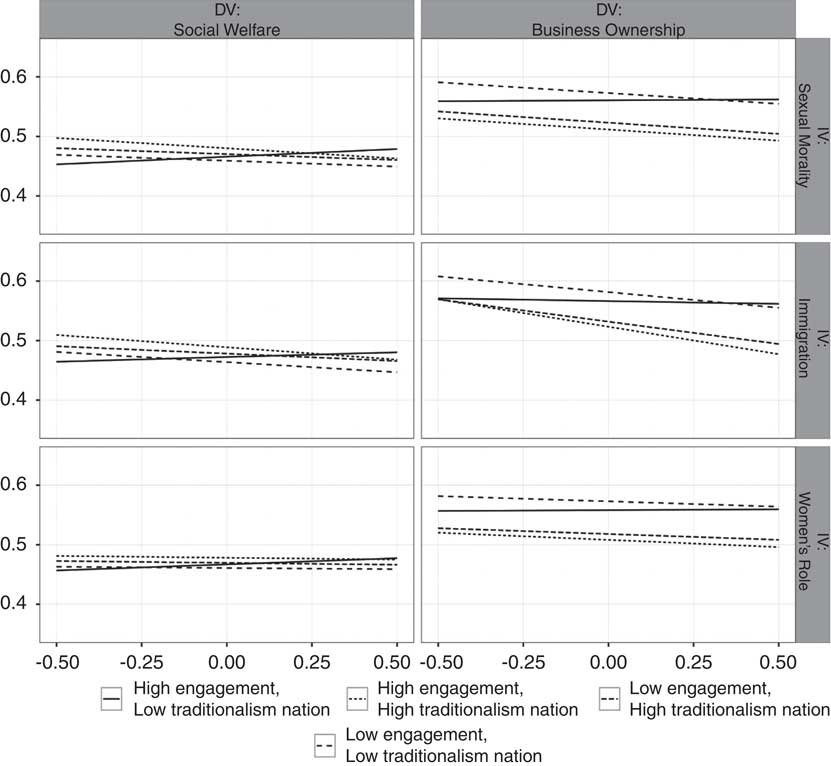

Individuals from relatively developed nations might be more likely to understand and express political identity by utilizing, the right–left dimension – particularly if they are very politically engaged. In the analyses testing two-way interactions, UNHDI significantly moderated cultural-economic conservatism relationships in two of six cases (see Appendix Tables F3 and F4), such that the effects of cultural on economic conservatism were less negative/more positive within developed nations. Meanwhile, the coefficient for UNHDI × political engagement × cultural conservatism was positive in all six cases, significantly so in four of six cases, and marginally significant in a fifth case (see Appendix Tables G3 and G4).

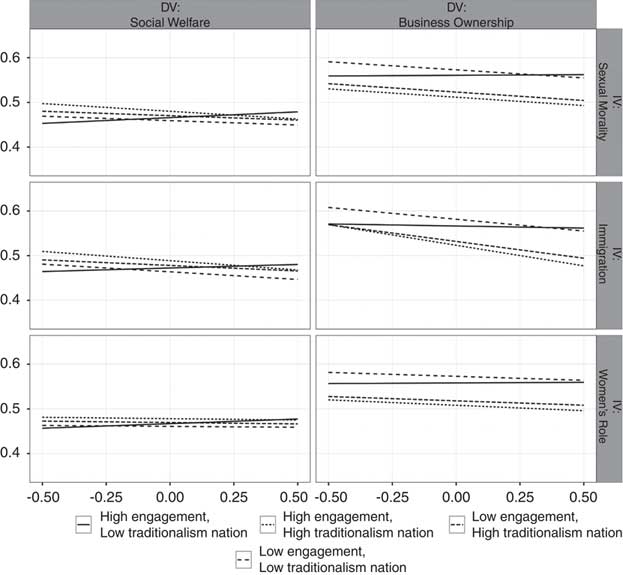

Figure 3 displays regression lines for the conditional effects of cultural on economic conservatism for all combinations of high and low political engagement and national development (high=+1 SD, low=−1 SD). The conditional effects of cultural on economic conservatism tended to be slightly negative, except among high political engagement people within developed nations, among whom they tended to be slightly positive or flat.

Fig 3 Conditional effects of cultural on economic conservatism based on UNHDI and political engagement

National traditionalism

National mean levels of sexual morality traditionalism constitute an important nation-level cultural characteristic that is relevant to modernization.Footnote 62 Nations were on average quite traditional in terms of sexual morality, with a mean of 0.75 (SD=0.17), with 0.5 representing the middle of the rating scale for the abortion and homosexuality items. Moreover, nations that were relatively low in sexual morality traditionalism tended to have substantial segments of their populations on both sides of the traditional–progressive divide. For example, the nation-level correlation between national traditionalism and a nation’s proximity to the midpoint of 0.5 on the traditionalism scale was −0.88 (p<0.001). Only 11 per cent of nations had traditionalism scores less than the scale midpoint of 0.5, and almost all of these nations had substantial percentages of citizens with traditionalism scores greater than 0.5, including several liberal Western nations such as Australia (47.8 per cent traditional), France (33.7 per cent traditional), Germany (43.3 per cent traditional) and Norway (34.1 per cent traditional).

Based on the theorizing of Johnston et al. pertaining to the American context, we reasoned that within relatively progressive nations where a prominent divide exists in lifestyle and cultural politics, right–left divisions on economic matters will often reflect a motivation to express a culturally based political identity.Footnote 63 This will result in greater right–left organization of cultural and economic attitudes, particularly among those who are highly exposed to political discourse. As displayed in Appendix Tables F5 and F6, national traditionalism was a significant negative moderator of the relationship between cultural and economic conservatism in four of six cases. The associations between cultural and economic conservatism were more negative/less positive within traditional nations. Meanwhile, as displayed in Appendix Tables G5 and G6, the national traditionalism × political engagement × cultural conservatism interaction term was significantly negative in all six cases. Figure 4 displays regression lines for the conditional effects of cultural on economic conservatism for all combinations of high and low political engagement and national traditionalism (high=+1 SD, low=−1 SD). The conditional effects of cultural on economic conservatism tended to be slightly negative, except among high political engagement people within low-traditionalism nations, among whom the slopes tended to be slightly positive or flat.

Fig. 4 Conditional effects of cultural on economic conservatism based on national traditionalism and political engagement

Do Background Characteristics Have Opposite Right–left Ideological Effects Across the Cultural and Economic Domains?

Why is cultural traditionalism more often associated with left-wing than right-wing economic views? This pattern might in part reflect the opposite (in terms of the right–left dimension) effects of some psychological and background characteristics across cultural and economic political attitudes. Specifically, evidence suggests that needs for security and certainty are often linked to right-wing cultural views but left-wing economic views among people with low levels of political engagement.Footnote 64 Also, low social class is associated with right-wing cultural views but left-wing economic views.Footnote 65 Thus it is possible that social class and needs for security and certainty help explain the prevalence of protection–freedom attitude organization in the face of discursive pressure toward right–left attitude organization.

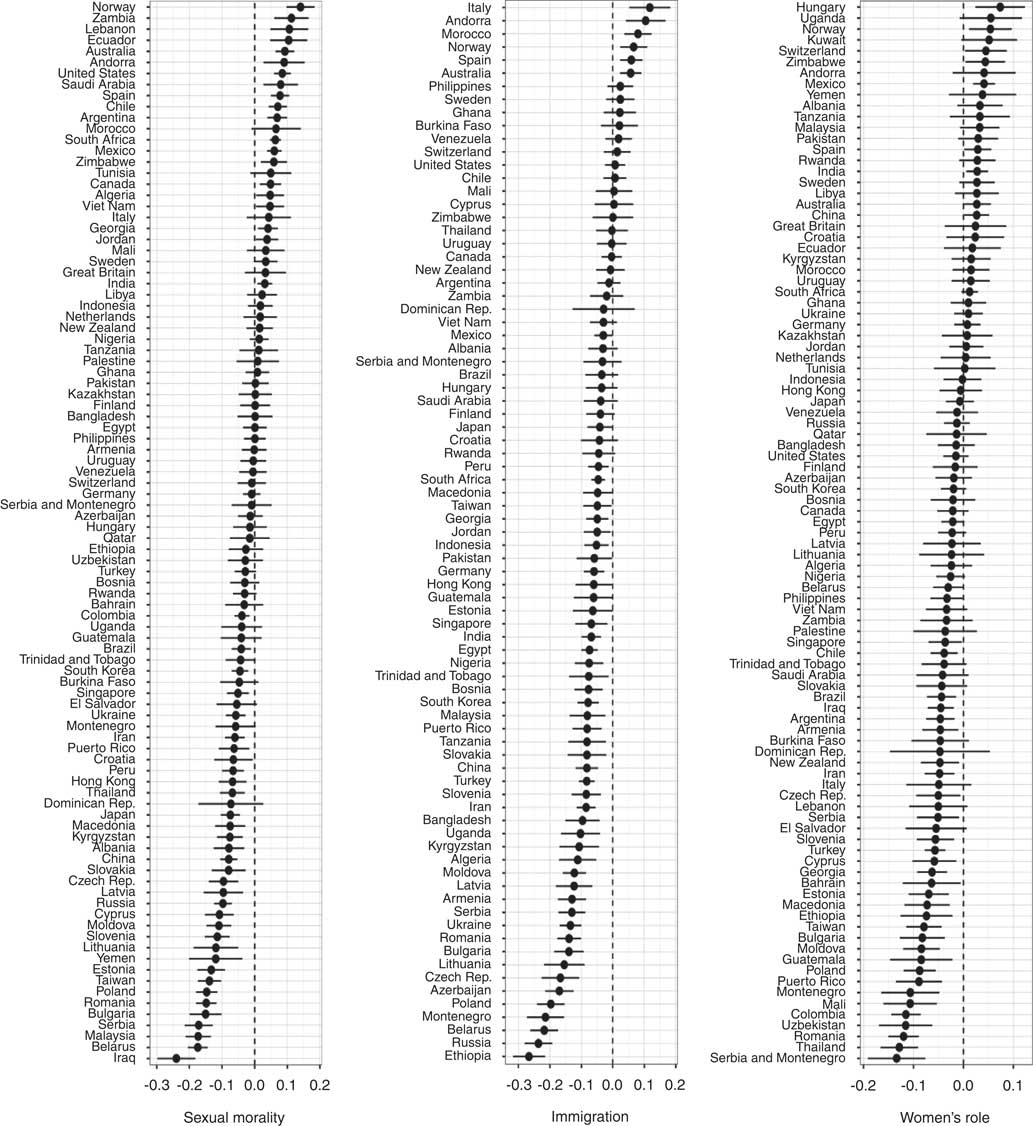

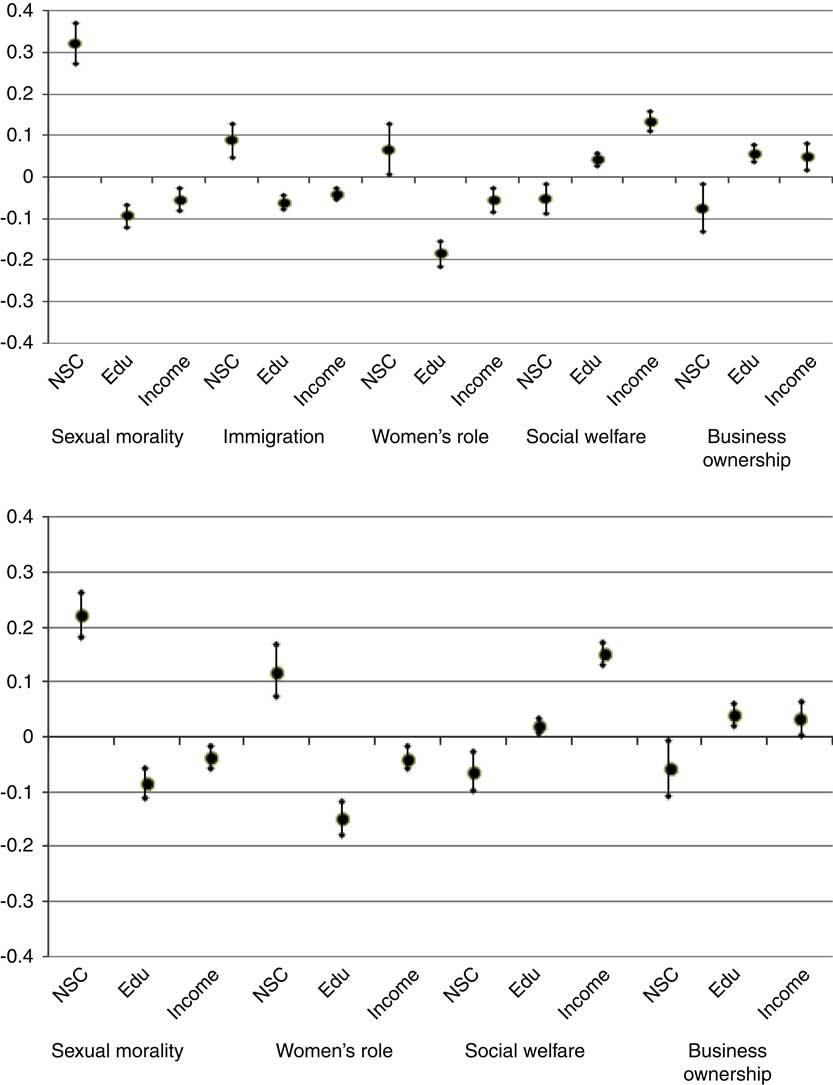

To further examine this possibility, we separately analyzed each of the WVS waves in which the needs for security and certainty measure was administered, Waves 5 from 2005–07 and 6 from 2010–14.Footnote 66 Within each wave, each available cultural and economic political attitude was individually regressed on needs for security and certainty, sex, age, education and household income, with random intercept and random slopes for needs for security and certainty, education and household income. Within each wave, each nation is represented with only one sample – thus respondents are nested within nations in two-level models. Predictors were centered around nation-year means. The formal model is displayed at the beginning of Appendix H. Of primary interest are the pooled effects of needs for security and certainty (γ 10), Education (γ 40) and Household Income (γ 50). These are displayed in Figure 5, with results for Wave 5 in Panel A and results for Wave 6 in panel B.Footnote 67

Fig. 5 Effects of needs for security and certainty, education and household income on conservative political attitudes in Wave 5 (top panel) and wave 6 (bottom panel). Note: pooled estimates from random coefficient regression analyses with variables coded to have a range of 1.00. Error bars represent 95 per cent confidence intervals.

The results from both waves consistently support the hypothesis that both needs for security and certainty and social class have opposite right–left relations across the cultural and economic attitude domains. Across the five analyses predicting a right-wing cultural attitude,Footnote 68 needs for security and certainty had a significant independent positive effect, and education and household income each had significant independent negative effects. Across the four analyses that predicted a right-wing economic attitude, needs for security and certainty had a significant independent negative effect, and education and household income each had significant independent positive effects.Footnote 69 Thus these background characteristics might in part underlie protection–freedom attitude organization.

CONCLUSION

Political elites and parties in many nations organize their cultural and economic attitudes along the right–left dimension.Footnote 70 If citizens organize their attitudes differently, then this mismatch has potential implications for our understanding of the psychological origins of political ideologyFootnote 71 as well as the quality of democratic representation.Footnote 72 The present research provided a large-scale cross-national test of the typical relationship between cultural and economic attitudes within mass publics around the world. Not only do we fail to find a typically positive relationship between right-wing (vs. left-wing) cultural and economic attitudes; we also find that a small negative relationship between these dimensions is more common. Such protection–freedom attitude organization was more common than right–left attitude organization within post-communist, traditional and low-development nations, as well as among low political engagement individuals. Meanwhile, right–left attitude organization outweighed protection–freedom attitude organization primarily among highly politically engaged individuals from relatively progressive and developed (that is, modernized) nations. Finally, our findings suggest that protection–freedom attitude organization might result in part from dispositional needs for security and certainty as well as social class exerting opposite (in terms of the right–left dimension) influences across the cultural and economic domains. These findings are consistent with the view that discursive sources of right–left attitude organization compete with dispositional and demographic sources of protection–freedom attitude organization,Footnote 73 yielding a net relationship between cultural and economic attitudes that is often small and that varies in sign across nations.

One implication of these findings concerns the psychological origins of right–left ideology. The present findings bolster the case for emphasizing differential origins of right-wing (vs. left-wing) attitudes across different substantive domains, and variability in attitude structure and origins across contexts and levels of exposure to political discourse.Footnote 74 This is consistent with evidence that characteristics commonly assumed to underlie a general conservative ideology – such as needs for security and certainty, authoritarian disposition and disgust sensitivity – often do not coincide with right-wing economic attitudes.Footnote 75 Thus these results raise further questions about the norm of focusing on unidimensional ideology as a correlate of basic psychological characteristics and states.

A second potential implication of these findings concerns democratic representation. As scholars have noted, a mismatch between elite and mass attitude structuring may imply poor representation.Footnote 76 With respect to this matter, Lefkofridi et al. and Van der Brug and van Spanje have noted the prominence of ‘left authoritarians’ – who are socially conservative but economically left wing – within Western European electorates.Footnote 77 They have also noted, however, that Western European parties have tended to combine right-wing economic views with traditional cultural views, and left-wing economic views with progressive cultural views. Thus, ‘compared to other simple packages of views, left-authoritarian attitudes are consistently and strikingly unrepresented by any party’.Footnote 78 Similarly, Ellis and Stimson highlighted the prevalence of ‘conflicted conservatives’ in the United States, who are economically left wing but gravitate toward a conservative self-label on the basis of the latter’s cultural connotations.Footnote 79 As Ahler and Brookman note, an ideologically mixed bag of attitudes might reflect a personally meaningful pattern of cultural and economic preferences that is not well captured by the right–left dimension.Footnote 80 The present findings suggest that this personally meaningful pattern might often involve cultural conservatism and left-leaning economic preferences – an orientation toward cultural and economic protection.Footnote 81

In this regard, the present findings might add useful context for understanding the rise and election of Donald J. Trump in 2016, the rise of extreme right parties in Europe and the 2016 British referendum vote to exit the European Union. In all cases, the motivation to protect national culture against foreign influence or ethnically dissimilar ‘others’ was an important factor in support.Footnote 82 But such cases also seem to involve some degree of motivation for economic protection,Footnote 83 even if this is of secondary importance.Footnote 84 While neither the standard right-wing nor left-wing attitude packages involve a unified culturally and economically protective attitude configuration, extreme right populist and ethnonationalist appeals might resonate with citizens who hold this attitude configuration.Footnote 85 Indeed, some extreme right parties in Western Europe appear to have made leftward movements on economic matters to attract left authoritarians who had previously been drawn to social democratic parties.Footnote 86 And Donald Trump’s campaign combined an economic posture to the left of the Republican norm (including fervent opposition to international trade agreements and promises of infrastructure spending and non-interference with social security and Medicare) with a theme of nationalism and appeals to racial antipathy.

Thus the present findings highlight the potential political importance of an ‘exclusive solidarity’Footnote 87 or ‘economic chauvinism’,Footnote 88 in which an economically interventionist and redistributive government is supported by cultural traditionalists who want benefits channeled exclusively to the ‘real’ members of the nation. In fact, across the culturally conservative attitudes considered in this article, it was opposition to immigration that was most frequently linked to left-wing economics, a finding that held when controlling for basic demographics including income and education. Anti-immigration sentiment is central to (though not singularly responsible for) support for extreme right parties and candidates,Footnote 89 and it is linked to attitudes toward ethnic groups and ethnically based notions of nationalism.Footnote 90 Thus the present findings are relevant to potential changes in the structure of political coalitions that might benefit extreme right and ethnonationalist parties and candidates.

The present results do not, of course, provide evidence of causal influences, such as influences of development, societal progressivism or political engagement on attitude structuring, or influences of social class and needs for security and certainty on political attitudes. With regard to nation-level relationships, development and culturally progressive values are associated with other cultural, structural and institutional characteristics that could be the driving influence, and if development or cultural progressivism do, themselves, exert a causal impact on attitude organization, it is uncertain why they do so. For instance, the present analyses did not gauge the role of party system characteristics – such as the number of parties,Footnote 91 party system polarizationFootnote 92 or the salience of particular issues within party systemsFootnote 93 – in mass attitude structuring. Future research might leverage data from manifesto coding or expert ratings of party positions to more directly examine the potential influence of elite attitude structure on mass attitude structure, although it would seem that this can only be done within democratic countries for which such data exist. It would also be worthwhile to examine how a nation’s degree of ethnic diversity relates to attitude organization, as group identity and conflict can influence one’s perspective on redistributive policy.Footnote 94 The present explanation centered on modernization and the rise of lifestyle politics within developed nations should be regarded as a working hypothesis that might guide future research and should be updated appropriately on the basis of new evidence. More compelling, however, is the evidence for the counter-intuitive conclusion that cultural conservatism has more often been associated with left-wing than with right-wing economic attitudes within nations around the world. Within mass publics, the organization of cultural and economic attitudes along the right–left dimension seems to be the exception rather than the rule.