Policy Significance Statement

Our participatory foresight exercise with Ukrainians displaced in Spain yields crucial insights for Ukrainian and the EU policymakers. By engaging displaced people in envisioning diverse future scenarios, we bridge the gap between conventional policy advice and the nuanced, lived experiences of displaced populations. This approach unveils critical uncertainties, such as energy levels to contribute and emotional dimensions, often overlooked by expert-driven analyses. The participatory foresight identified four scenarios of possible migration of Ukrainians: exhaustion return, energetic return, virtual return, and disconnection; it provides a unique lens into the complexities of return migration, emphasizing the need for flexible, inclusive, and anticipatory policies. Ukrainian policymakers can leverage these insights to craft responsive return and reintegration strategies for exhaustion, energetic and virtual return scenarios, addressing challenges like stigma, trauma, conflicting views, and need for digitalization, while EU policymakers could work with reintegration of those from virtual return and disconnect scenarios, and support tailored return to those from exhaustion and energetic return scenarios. While these scenarios represent speculative possibilities, collectively contemplating them enhances the futureproofing of policy measures. Our research advocates for anticipatory and inclusive migration governance, empowering policymakers to navigate uncertainties and foster a more holistic approach to policy development.

1. Introduction

The current Russian invasion has caused widespread displacement of Ukrainians, with a considerable number (200,000) seeking refuge in Spain (Eurostat, 2024). This significant population upheaval poses a profound challenge, shrouded in uncertainty, regarding the potential for their return to Ukraine (CES, 2023). The implications of this uncertainty extend beyond the individuals involved, impacting both Ukraine and the broader landscape of migration policies (Guild and Groenendijk, Reference Guild and Groenendijk2023).

Predicting return migration is extremely difficult because it involves many complex and uncertain factors (King and Lulle, Reference King and Lulle2022). The reasons why migrants decide to return home are influenced by their personal goals, financial matters, social connections, and the broader socio-political context (Haug, Reference Haug2012). Numerous studies have looked into how we can better understand and predict return migration, ultimately recognizing its complexity (Cassarino, Reference Cassarino2004; Bijak and Czaika, Reference Bijak and Czaika2020; Mencutek, Reference Mencutek2022).

The return migration situation in Ukraine is also marked by unpredictability and mixed signals. While the International Organization for Migration (IOM) observes an increasing number of Ukrainians returning home despite the ongoing war (UN, 2023), other studies suggest that many may opt to stay in host countries (Culbertson and Szayna, Reference Culbertson and Szayna2023; Harmash, Reference Harmash2023; OECD, 2023). A report by the Centre for Economic Strategy (CES) highlights that a majority (63%) of Ukrainians currently residing abroad have intentions to return to Ukraine (CES, 2023). Meanwhile, a report from the Center for Immigration Studies challenges the notion that many Ukrainians want to return home, citing pre-invasion data indicating that one in four adults in Ukraine expressed a desire to migrate, with the European Union (EU) being a prevalent desired destination (Rush, Reference Rush2022). The latest Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) report shows that a significant portion of Ukrainian displaced remain undecided about returning (OECD, 2023).

Furthermore, refugees are frequently expected to return to their countries of origin. The idea of return for forced migrants (e.g., due to war) is often framed as beneficial for all parties involved (Sinatti, Reference Sinatti2015; Bradley, Reference Bradley2021). This perspective largely stems from a sedentary narrative that asserts a naturalistic connection between individuals and their homeland (Omata, Reference Omata2013). Indeed, many do want to return to their homeland, but many do not. However, refugee perspectives are often marginalized in policy discussions regarding return (Kvittingen et al., Reference Kvittingen, Valenta, Tabbara, Baslan and Berg2019).

The complexity of this situation underscores the need for inclusive and innovative approaches to understand the future dynamic of Ukrainian migration. Among the diverse array of such approaches, the application of participatory foresight methodologies emerges as a promising avenue in migration studies. Participatory foresight is a forward-looking approach that also incorporates the perspectives and insights of various stakeholders, particularly those directly impacted by study. This method acknowledges the intricacies and uncertainties of the future, emphasizing the need for a collective effort that complements traditional expert-driven methods (Neuhoff et al., Reference Neuhoff, Simeone and Laursen2023).

Despite the potential significance of participatory foresight in migration studies, its exploration remains limited. The integration of participatory foresight holds promise for a more inclusive understanding of potential migration and displacement integration futures, emphasizing a collaborative approach that actively involves those directly impacted by migration dynamics.

Our research focuses on testing the application of participatory foresight methodologies to explore the future of migration of displaced Ukrainians. By actively engaging with displaced Ukrainians in Spain, we conducted horizon scanning to gather their insights on emerging signals and trends related to migration, identify potential uncertainties, and develop scenarios surrounding migration trajectories.

The study’s broader objective is to translate the results of horizon scanning, uncertainty mapping, and scenario building into data-driven yet people-centered policy implications. These results have the potential to inform data-driven policymaking in Ukraine and the EU by enabling us to envision alternative futures and anticipate potential challenges and opportunities associated with future (return) migration of displaced Ukrainians. The goal of such exercises is to provide a variety of narratives that highlight different aspects of migration, thereby enhancing the future-proofness of policy decisions by considering a range of potential trajectories (Bourgeois et al., Reference Bourgeois, Penunia, Bisht and Boruk2017).

Our research prioritizes the experiences of those who have faced the challenges of displacement and return, recognizing their invaluable insights as essential components of the broader discourse on Ukraine’s future. By challenging dominant knowledge paradigms, our research contributes to promoting epistemological justice and participation, ultimately fostering a more inclusive understanding of migration dynamics.

In addition to providing insights and practical participatory foresight tools, our research offers recommendations for Ukrainian and EU policymakers, practitioners, and researchers in the field. It also serves as a tool to challenge dominant knowledge paradigms, fostering a more inclusive and nuanced comprehension of migration dynamics and their consequences.

2. Background

To effectively navigate the future and develop possible policy implications, it’s essential to first understand the current and past situations, trends, and policies regarding Ukrainian migration to the EU and specifically to Valencia, Spain. In this background section, we delve into precisely these aspects, aiming to provide a comprehensive overview that lays the foundation for our analysis and foresight exercises.

2.1. Migration policies approaches in the EU and Ukraine

The migration policy of Ukraine is a crucial aspect of the country’s post-war recovery efforts (CabMin, 2022; IOM, 2023; Moens and Barigazzi, Reference Moens and Barigazzi2024). The Ukrainian government has established working groups to develop a comprehensive plan for post-war recovery, which includes a group working on measures to facilitate the return and integration of citizens displaced abroad (CabMin, 2022). The group is working with initiatives like cultural and educational campaigns to encourage displaced people to return and reconstruction efforts for housing and public services (CabMin, 2022). After the work of this group, changes have been made to Ukraine’s current migration policy with a focus on incentivizing return and fostering ties with displaced individuals (CabMin, 2024).

In addition, the Ukrainian government is actively working with the IOM to shape migration policies that will encourage and enable the return of especially vulnerable Ukrainian displaced (IOM, 2023). For example, IOM is improving conditions in areas experiencing high numbers of spontaneous returns through humanitarian, reconstruction, and recovery programs (IOM, 2023).

Ukraine is currently discussing with EU officials to shape future migration policies, aiming to encourage the return of its citizens while the war puts pressure on resources. Now, with the EU under temporary protection directive expiring in 2025, Ukraine seeks clarity on future rules and potential support until the war ends. While the details are still unclear, promotion of the return is a clear direction taken by the Ukrainian government. For example, Zelenskyy’s Presidential Office Advisor, Serhiy Leshchenko, said in an interview with a Swiss paper: “I believe that host countries should stop supporting refugees so that they can return home” (Boss and Lipkowski, Reference Boss and Lipkowski2024).

From the perspective of the EU, efforts have been made to manage the Ukrainian displacement situation through the implementation of a Temporary Protection Directive for Ukrainian residents fleeing their country. This directive provides immediate rights and protections upon entry to EU countries, encompassing residence, employment, healthcare, and education.

One of the key distinctions that set the Temporary Protection Directive apart from traditional refugees or asylum statuses is its immediate response to crises. It offers swift relief to those affected by conflicts, ensuring their well-being and protection. While this immediate response is beneficial, it creates challenges for displaced people in making long-term plans. The uncertainty about their future residence and status after the temporary protection period expires is a major source of concern and instability (Guild and Groenendijk, Reference Guild and Groenendijk2023).

2.2. Migration to the EU, Spain, and Valencia due to Russian invasion

Since the onset of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, millions of Ukrainians have been compelled to flee their homeland and seek refuge in the EU and other countries. The EU responded swiftly to the crisis by launching a special Temporary Protection Directive for Ukrainian residents. This Directive allowed them to enter the EU and enjoy extensive rights and protections (Guild and Groenendijk, Reference Guild and Groenendijk2023).

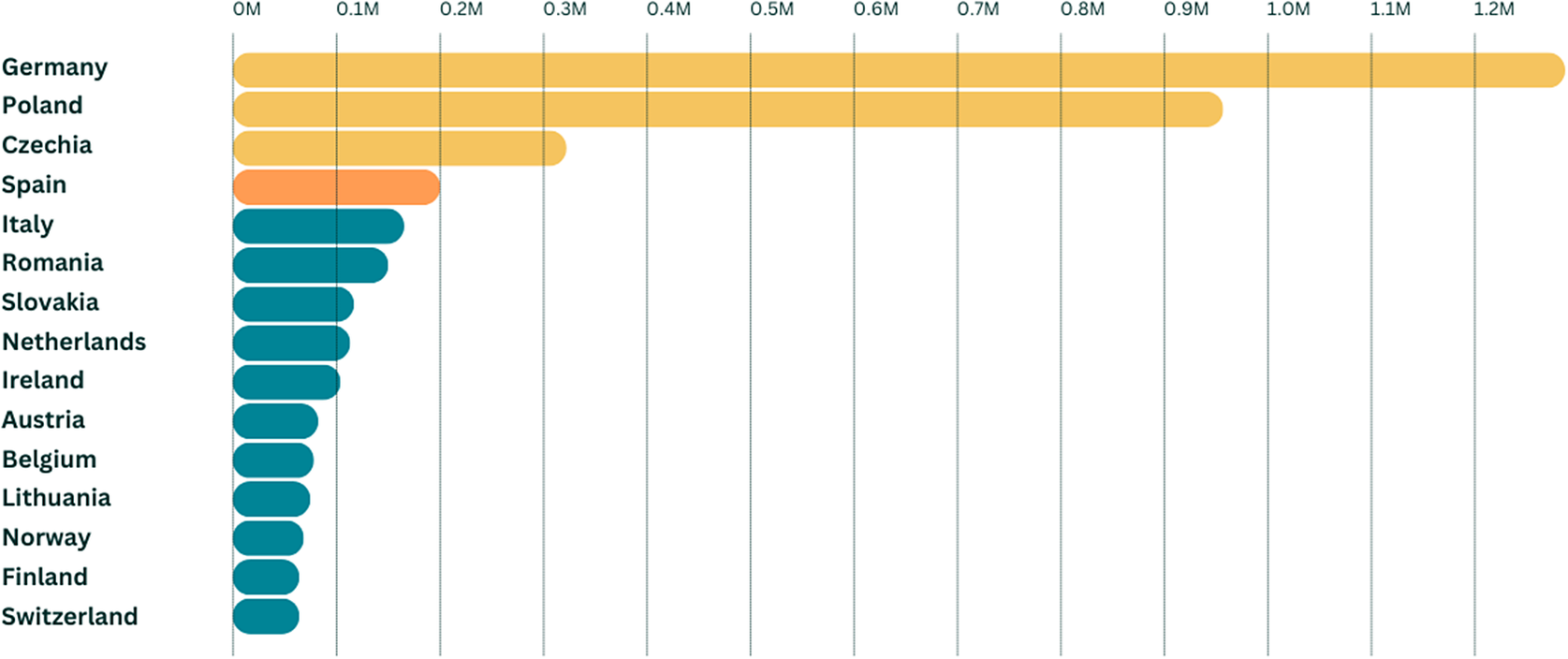

As of March 2024, over 4 million people from Ukraine have availed themselves of the temporary protection mechanism (Eurostat, 2024). Spain has welcomed nearly 200,000 Ukrainian displaced persons who were granted temporary protection (La Moncloa, Reference La2023; Eurostat, 2024), positioning it as the fourth-largest destination for refugees in Europe, following Poland and Germany, Czech Republic as illustrated in Figure 1 (Elcano Royal Institute, 2023; Eurostat, 2024). Of these Ukrainian displaced persons granted temporary protection in Spain, a total of 61.1% are women (122,400) and 38.9% are men (77,754). By age group, 31.3% are under 18, 26.6% are between 19 and 35, 35.4% are between 36 and 64, and 6.7% are over 65 (La Moncloa, Reference La2024). Remarkably, the Valencian Community hosts the highest number of Ukrainians at 50,066, leading among the hosting regions in Spain. It is followed by Catalonia, Andalucia, and Madrid (La Moncloa, Reference La2023).

Figure 1. Beneficiaries of temporary protection tailored to individuals displaced from Ukraine after February 24, 2022, due to the incursion by Russian military forces. Sample of the countries in the top 15 positions (Source: Authors, based on data from the Eurostat (2024) on temporary protection).

This influx can be attributed in part to previous migration dynamics shaped before the war. Notably, Italy, Czech Republic, Germany, and Spain, as EU countries, each host over 100,000 Ukrainian residents. Specifically, within Spain, data from 2014 reveals that Ukrainian immigrants were predominantly concentrated in four earlier-mentioned regions: Madrid (22%), Catalonia (20.1%), the Valencian Community (18.2%), and Andalusia (15%) (Stanek et al., Reference Stanek, Hosnedlová and Brey2016).

In Spain, like in other EU countries, Ukrainian displaced are currently receiving support through the EU’s Temporary Protection Directive, which has been extended until at least March 2025. The process for Ukrainian nationals to obtain this status and access essential services in Spain appears to be relatively straightforward, facilitated by dedicated reception centers and legal aid services (EUAA, 2022). The labor market integration of Ukrainians displaced in Spain seems to be in line with the European average of 40% (Benedicto, Reference Benedicto2022; European Network on Statelessness, 2024; EMN, 2024). However, many displaced Ukrainians face difficulties in finding permanent housing, leading to a reliance on temporary accommodations such as flats and reception centers, indicative of a shortage of long-term housing solutions (Eurofound, 2024). The situation has been exacerbated by delays in receiving the promised €400 monthly subsidy, which was suspended as of September 2023 (Trelinski, Reference Trelinski2023). Despite these challenges, Eurostat data (2024) indicates a noticeable increase in the number of Ukrainians seeking shelter in Spain, rising from approximately 180,000 in 2023 to 200,000 in 2024.

3. Theoretical framework

3.1. Understanding return migration dynamics

Return migration, broadly defined as the movement of individuals from a host country back to their country of origin, nationality, or habitual residence, has been explored extensively in the context of international labor migration, often overshadowing the experiences of refugees, asylum seekers, and internally displaced people (IDPs) (IOM, 2019).

Return migration dynamics have been the subject of numerous studies, looking at i) aspirations and decisions to return, ii) the return process, and iii) reintegration (Mencutek, Reference Mencutek2022). First strand of return migration studies focuses on decisions and motivations to return that are shaped by complex interactions between economic, education, and demographic variables, alongside factors such as migration plans, expectations, and societal objectives and similar (e.g., Cassarino, Reference Cassarino2004). The second strand of return migration scholarship delves into the organization of returns, especially for refugees, asylum seekers, and IDPs. It scrutinizes pre- and post-return assistance, practices, and interventions, emphasizing legal compliance, livelihood development, and equal citizenship (e.g., Cole and Belloni, Reference Cole and Belloni2022). The third strand focuses on the reintegration of returnees, considering factors like human and financial capital, economic opportunities, social networks, and host community reception (De Bree et al., Reference De Bree, Tine and De Haas2010).

Despite the growing number of publications in the area, our knowledge of return migration is still fragmentary, and there are challenges in measuring the phenomenon due to the lack of internationally comparable statistical information and difficulties in defining return migration (OECD, 2022).

In addition, return migration’s uncertain and unpredictable nature is characterized by volatility, ambiguity, and complexity (Bijak et al., Reference Bijak, de Vilhena and Potančoková2023; King and Lulle, Reference King and Lulle2022; OECD, 2022). This unpredictability is exemplified by the displaced population return after the Yugoslav Wars from 1991 to 2001 (OECD, 2023). In the aftermath of active warfare in Bosnia, the majority of Bosnian refugees did not return home, contrasting sharply with the mass return of Kosovar refugees to Kosovo after the conflict (OECD, 2023). This volatility underscores the intricate interplay of factors shaping return migration, highlighting the need for innovative methods to delve into this intricate tapestry of factors and influences, such as foresight (Bijak et al., Reference Bijak, de Vilhena and Potančoková2023).

Before the war, return migration to Ukraine had not received significant scholarly attention. Instead, research predominantly focused on the reasons behind Ukrainian emigration (Vakhitova and Fihel, Reference Vakhitova and Fihel2020; Vakhitova et al., Reference Vakhitova, Coupe and Sologoub2013; Libanova, Reference Libanova2019). Economic and social factors, including low GDP per capita, low wages, and challenges in doing business, have contributed to significant emigration from Ukraine, making Ukraine one of the main migrant-sending countries in Europe, with thousands of Ukrainians working in Czech Republic, Italy, and Poland until the war (Vakhitova et al., Reference Vakhitova, Coupe and Sologoub2013; Libanova Reference Libanova2019; Vakhitova and Fihel, Reference Vakhitova and Fihel2020). In this regard, Vakhitova and Fihel (Reference Vakhitova and Fihel2020) noted that Ukraine could have shared the previous experience of Central European countries such as the Baltic States, Poland, and Slovakia and would see a flow of return migration in the near future. During the 1990s and early 2000s, these countries experienced temporary outflows of citizens, transitioning to permanent migration patterns, while in recent years, many Central and Eastern European countries have seen an increase in the number of returning migrants.

Limited existing studies on return migration to Ukraine before the war highlight a general reluctance among some migrants to return home, citing mainly economic factors (Ryndzak and Bachynska, Reference Ryndzak and Bachynska2022)—low wages and the overall economic situation in Ukraine. In addition, the length of stay abroad was shown to be a key determinant (Vakhitova and Fihel, Reference Vakhitova and Fihel2020), with longer absences weakening ties to the home country. A study from 2010 interviewed labor migrants returning from Italy and Spain to Ukraine, revealing two main reasons to return in two groups: the ‘Disappointed’ returning due to disillusionment with their life abroad, and the “Missioners” achieving financial goals or completing missions. It highlighted that reintegration for Ukrainian labor migrants was very challenging for both groups, involving legal, social, and psychological complexities, such as documentation challenges, loss of parental roles, discrimination, and psychological struggles such as loneliness and cultural shock (Ivaschenko-Stadnik, Reference Ivaschenko-Stadnik2013).

The question arises as to whether current displaced Ukrainians will encounter similar aspirations and challenges as previous return migrants, underscoring the importance of understanding the continuity and evolution of migration dynamics in Ukraine.

3.2. Participatory foresight and migration studies

Strategic foresight, primarily utilized by strategic planning units, for example, within business organizations, encompasses various methodological approaches (Iden, Methlie, and Christensen, Reference Iden, Methlie and Christensen2017; Dahlgren and Bergman, Reference Dahlgren and Bergman2020; Gall and Allam, Reference Gall and Allam2022; UNDP, 2022; Tully, Reference Tully2023). In essence, it involves exploring the future by searching for potential trends and developments, known as a “horizon scan,” focusing on critical drivers, for example, technological advancements, often structurized using STEEP-V or PESTLE frameworks (Iden, Methlie, and Christensen, Reference Iden, Methlie and Christensen2017; Dahlgren and Bergman, Reference Dahlgren and Bergman2020; Gall and Allam, Reference Gall and Allam2022; UNDP, 2022; Tully, Reference Tully2023). This initial scan identifies critical uncertainties, paving the way for constructing future scenarios to test existing and new policies for resilience and compatibility with potential emerging futures (Iden, Methlie, and Christensen, Reference Iden, Methlie and Christensen2017; Dahlgren and Bergman, Reference Dahlgren and Bergman2020; Gall and Allam, Reference Gall and Allam2022; UNDP, 2022; Tully, Reference Tully2023). The primary objective of this approach is to augment traditional strategic planning methodologies and bolster the capabilities of organizations and governments to anticipate and adapt to changing circumstances.

The integration of foresight methodologies into migration policy discussions has been advocated for its capacity to address the complexities and uncertainties inherent in migration dynamics (Bijak et al., Reference Bijak, de Vilhena and Potančoková2023). Traditional policy frameworks often struggle to keep pace with the rapidly evolving landscape of migration, where multifaceted factors intertwine to shape individuals’ decisions. Foresight provides a valuable tool for policymakers to move beyond reactive measures, fostering a forward-looking and anticipatory approach (Jevšnik and Toplak, Reference Jevšnik and Toplak2014). By considering a spectrum of possibilities, policymakers are better equipped to develop adaptive strategies that account for diverse outcomes (IOM, 2019). This goes in line with the concept of anticipatory governance (Guston, Reference Guston2014). In this specific context, it entails preparing for multiple plausible futures rather than predicting a single, predetermined outcome.

The growing importance of foresight in migration studies is evident from various initiatives and research projects that aim to anticipate and plan for the future of migration (Bettini, Reference Bettini2017; Bijak et al., Reference Bijak, de Vilhena and Potančoková2023; OECD, 2020). While these endeavors are commendable, it’s crucial to recognize that traditional foresight practices often involve exclusive participation from small groups of influential actors such as expert futurists, politicians, scientists, managers, and decision-makers, possessing specialized knowledge about the future. However, Hines and Gold (Reference Hines and Gold2013) assert that no single group or expert can monopolize knowledge about the future. Participatory foresight, on the other hand, is opening up the foresight process to include less privileged perspectives allows for a more comprehensive approach, yielding at least three key benefits: filling knowledge gaps by integrating diverse insights and having more complete picture of the future, ensuring a more equitable distribution of opportunities and benefits, promoting transparency and legitimacy in following policy-making and fostering social learning, empowering citizens to actively contribute to enhancing that future (Neuhoff et al., Reference Neuhoff, Simeone and Laursen2023).

In the field of migration studies, participatory foresight means involving those who have experienced displacement firsthand. In the dynamic migration landscape marked by uncertainties, participatory foresight emerges as a powerful tool for navigating the intricacies of migration, encouraging a holistic understanding in addition to expert-based elaborations, while recognizing the agency of displaced populations. As migration governance paradigms shift towards people-centered and rights-based (UN, 2018) and inclusive approaches (Arnstein, Reference Arnstein1969; Rowe and Frewer, Reference Rowe and Frewer2000), participatory foresight stands as a beacon for a more inclusive, equitable, and community-driven understanding of migration.

Despite its promise, participatory foresight is underused in migration studies. Examples from other contexts, such as urban studies (Gouache, Reference Gouache2021; Dixon and Tewdwr-Jones, Reference Dixon and Tewdwr-Jones2023), highlight feasibility and benefits of involving experiences of those intimately familiar with the lived complexities.

Hence, our research endeavors to navigate the uncharted territory of participatory foresight in the return migration field, focusing on Ukrainians displaced in Spain. By actively engaging with this displaced population, we aim to empower them to contribute to the exploration of return migration scenarios. In doing so, we aim to center the experiences of the individuals directly affected by displacement and return. Recognizing their invaluable insights and perspectives, we consider them as essential components in the broader discourse on migration policy and its implications for Ukraine’s future, ultimately contributing to the advancement of anticipatory migration approaches.

4. Methodology

4.1. Participatory process and methods

We adopted a Participatory Action Research approach, emphasizing collaboration between researchers and participants. This allowed Ukrainians displaced to Valencia, Spain, to actively engage in the research. Complementing the PAR approach, we integrated elements of Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR), ensuring the study was both participatory and directly beneficial to the community involved (Smith, Reference Smith2021; Corbetta, Reference Corbetta2007).

Our research team was comprised of a Ukrainian researcher who had personally experienced forced migration due to the 2022 Russian invasion, offering invaluable firsthand insights. The second researcher specialized in participatory methodologies, ensuring a well-rounded and inclusive research approach.

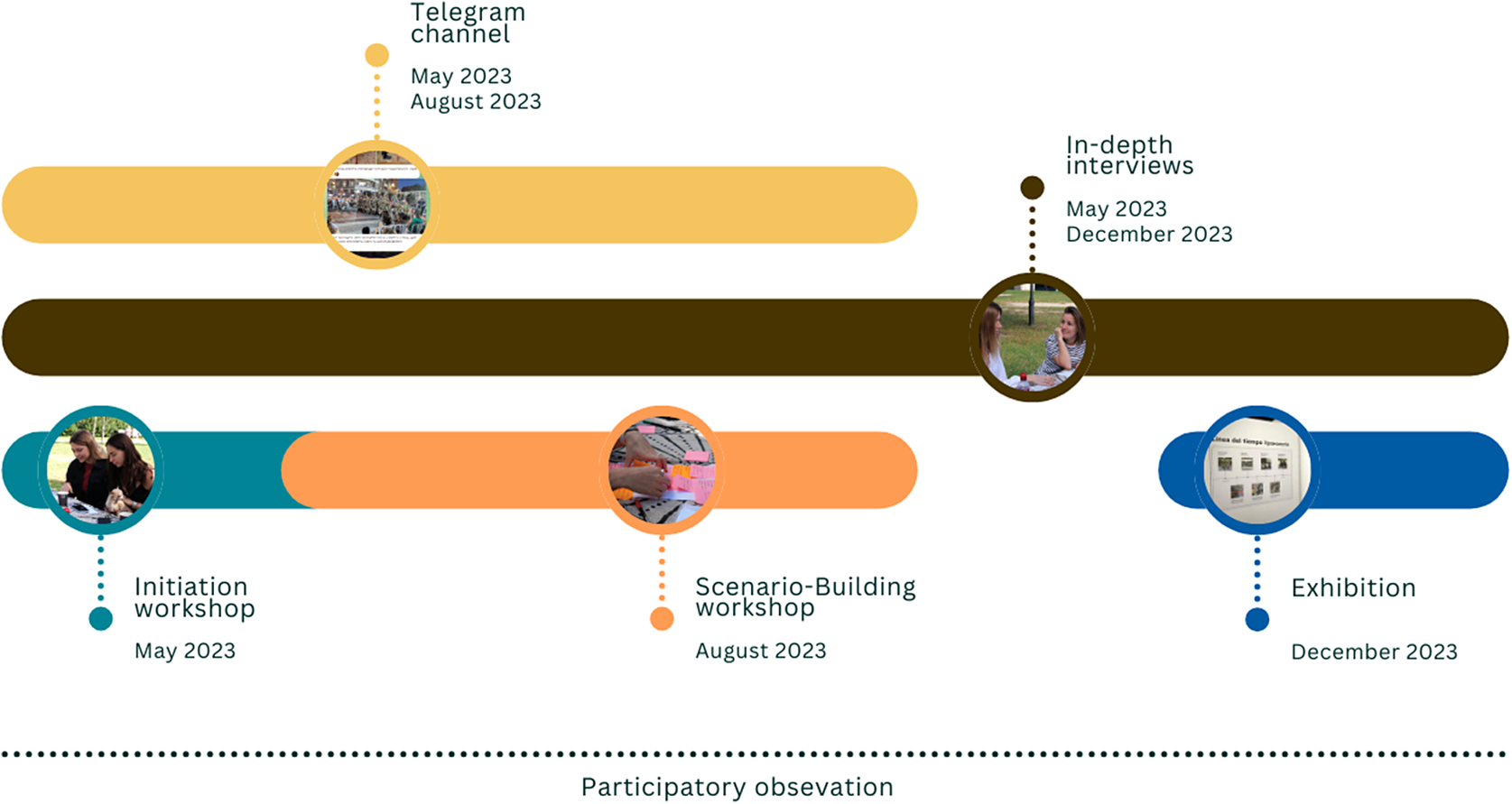

Building upon the strategic foresight methodology outlined in our theoretical framework, we initiated a collaborative horizon-scanning exercise focused on the migration of displaced Ukrainians. This endeavor facilitated the identification of weak signals and critical uncertainties perceived by the participants, leading to the crafting of scenarios for exploration and analysis. A series of workshops, interviews, and participatory observation sessions were conducted to facilitate, support, and make sense of this process (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Participatory process timeline (Source: Authors).

We initiated a collaborative process that actively engaged community members in all stages of the research. This began with an “Initiation workshop in May 2023” where 20 displaced Ukrainians and researchers convened to discuss the research process, from problem identification to data collection and analysis. Facilitated by the Ukrainian researcher, the workshop led to a clear reframing of the research question, shifting the focus from the future of return migration to Ukraine to exploring the migration futures of displaced Ukrainians. This shift aimed to produce practical outcomes and solutions addressing real-world issues relevant to the participants.

We further continued the workshop with a horizon scan focused on critical drivers such as the migrations of displaced Ukrainians. We collected initial weak signals, but it became evident that more engagement was needed. Thus, a dedicated “Telegram channel” emerged as a solution and was created by the researchers to serve as an inclusive space for ongoing discussions, information exchange, and the collection of diverse weak signals from the community. Over a 3-month period, participants shared emerging signals, trends, and insights related to migration dynamics and return migration. This real-time, asynchronous communication platform enabled continuous dialogue and knowledge exchange among participants, enriching the research process with diverse perspectives.

Following this, participants gathered for a “Scenario-Building workshop in August,” where the results of the collective horizontal scanning were presented by the researchers. The Ukrainian researcher further moderated the session with earlier prepared steps. She facilitated the discussion and selection of the two main critical uncertainties surrounding migration, laying the groundwork for the construction of future scenarios. The uncertainties and scenario names were developed collaboratively by participants. The researchers’ role during the workshop was primarily facilitative, ensuring that the discussions progressed smoothly and that all participants had the opportunity to contribute their insights and perspectives. While the researcher did utilize simple pre-prepared structure to moderate the discussions (present collective horizon scanning results, energize discussion about uncertainties, identify two main uncertainties, and build scenarios based on them), she rather facilitated a collaborative and inclusive environment where participants could collectively craft scenarios.

In addition to these group activities, we conducted “in-depth semi-structured interviews” with 20 displaced Ukrainians to gain deeper insights into their lived experiences, migration aspirations, and challenges. Interviews with elements of a biographical interview were carried out between May and December 2023 in Valencia, Spain. A semi-structured interview guide comprising open-ended questions facilitated detailed responses to explore the individual dynamics of migration, specifically focusing on complexity of the decision of returning or not. It should be stressed, however, that the order of questions and their form depended largely on the course of the conversation itself. An attempt was made to give the interviews a conversational character. The researchers encouraged the interviewees to speak freely and tell their life stories spontaneously. Only when the topic of the conversation went too much off the course relevant to the purpose of the study, the researchers asked other questions to bring the conversation back on track or to deepen some issues that had not been discussed in detail earlier. Interviews were conducted either in person or via video conference based on participants’ preferences, conducted in their native language, and ranged from 30 minutes to 1,5 h. The focus of the interviews was to explore various aspects of migration, including participants’ decisions regarding returning to Ukraine or remaining in their host country.

Furthermore, “participatory observation” (Kawulich, Reference Kawulich2005; Corbetta, Reference Corbetta2007) was carried out exclusively during the participatory process. Supported by a field diary, this observation method enabled us to immerse ourselves in the participants’ interactions and the unfolding process. It proved particularly valuable during workshops, informal gatherings, and conversations or through the Telegram group, fostering continuous reflection by the researcher.

Finally, we organized an “exhibition” to present our research findings, allowing participants to witness the progression of the study, recognize their contributions, and share these insights with the broader community (UPV, 2023). Additionally, the exhibition enabled us to continue collecting emerging signals and engage with attendees through participatory exposition methods, including interactive displays and photographic documentation.

Researchers frequently met to discuss observations and engaged in continuous critical discussions on their biases, assumptions, and power dynamics, promoting self-awareness throughout the research process. Coming from a position as an ‘insider view’ in the field of Ukrainian research had its advantages and challenges (Wilkinson-Weber, Reference Wilkinson-Weber2012; Szolucha et al., Reference Szolucha, Timko, Ojani and Korpershoek2023). On one hand, it facilitated access to the field and helped establish connections with the participants. However, this positionality may have influenced the researcher’s sense of empathy and could have led to blind spots in the research, presenting a limitation. As Howlett and Lazarenko (Reference Howlett and Lazarenko2023) noted, the necessity to maintain a distinction between personal and professional lives during fieldwork made the research inherently participatory in nature. Coming from the position of outsider Spanish researcher maintained an ‘observer’ role and analytical distance, in order to be able to describe and interpret the cultural context from an external, academic perspective. This allowed for the critical balance between participation and observation, as described by (Kawulich, Reference Kawulich2005; Wilkinson-Weber, Reference Wilkinson-Weber2012; Szolucha et al., Reference Szolucha, Timko, Ojani and Korpershoek2023).

Thus, researchers have taken several steps to distinguish their own conceptual frameworks from those of the participants, including researcher positionality, a strong focus on participatory approach, continuous reflection and dialogue, an emphasis on participant experiences, and triangulating data from multiple sources (Wilkinson-Weber, Reference Wilkinson-Weber2012; Szolucha et al., Reference Szolucha, Timko, Ojani and Korpershoek2023).

4.2. Participants

Participants were recruited through various channels, including newly established online groups such as Telegram and Facebook groups catering to the recently arrived Ukrainians in Valencia. Additionally, an open call was extended to Ukrainian diaspora organizations in these cities. The selection criteria ensured that participants were Ukrainians displaced due to the Russian invasion post-February 24, 2022. The participants encompass a diverse range of ages, backgrounds, experiences, and aspirations, sharing a common identity as displaced individuals.

In detail, there are 18 female participants and 2 male participants in the study, reflecting a predominantly female demographic of the displaced Ukrainians. Ages span from 19 to 68 years, with an average age of approximately 40. Participants exhibit a diverse range of educational backgrounds, with the majority holding higher education degrees such as bachelor’s or master’s, and two participants possessing doctorate degrees and four participants with middle education. Notably, full-level education is not unique to this group but rather characteristic of the Ukrainian population, which tends to have individuals with higher formal qualifications compared to many other countries, surpassing the EU average significantly by 2020 (OECD, 2023). The participants originate from various regions of Ukraine, including Odesa, Ternopil, Kyiv, Dnipro, Kharkiv, Symu, Rivne, Lviv, Herson, and Donetsk. In terms of family status, a majority are married, with their husbands residing in Ukraine. However, four participants are divorced or separated, with three experiencing divorces after the onset of the war. And four are living with their Ukrainian partners in Spain. Additionally, most participants were parents who had one or two kids with them.

Regarding employment status, a portion of participants are unemployed or not officially employed (doing cleaning, baby sitting), while some are employed or pursuing further education. Seven individuals are working full-time in Spain or engaging in remote work with Ukrainian and other international companies. Three participants are part of the support programs, such as the Red Cross refugees support program, that is, a part of the Spanish Government’s reception and integration support program for asylum-seekers without sufficient economic resources (UNHCR, 2024). Housing arrangements among participants vary, with some able to rent rooms or flats, but many are still living with relatives (diaspora), and a few residing in unique arrangements such as with a host family or Red Cross Support program. Housing is the main concern for this particular group. Economic status among participants in Ukraine (before the war) ranges from low to high, with a notable portion falling into the middle-economic category (the full list of anonymous details of the participants can be provided on request).

5. Results

Here, we offer a comprehensive overview of findings derived from the participatory foresight process conducted with displaced Ukrainians residing in Spain. We navigate through the realms of horizon scanning, identifying critical uncertainties, and crafting future scenarios. Furthermore, we elucidate the interconnectedness between these scenarios and their possible implications on both EU and Ukrainian migration policy landscapes.

5.1. Horizon scanning

Horizon scanning, within the framework of participatory foresight, involves actively engaging displaced Ukrainians in the process of identifying emerging trends and weak signals that may influence return migration dynamics. Through first an initial workshop and after the Telegram channel, participants collectively monitor and share a wide range of signals, including political developments, economic conditions, social dynamics, cultural shifts, environmental changes, and technological advancements. During the scenario – building workshop, we have structured those signals using a PESTEL framework—a tool commonly employed in foresight studies to evaluate Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental, and Legal factors (e.g., Korhonen, Reference Korhonen2018; Järvenpää, Kunttu and Mäntyneva, Reference Järvenpää, Kunttu and Mäntyneva2020; Demneh, Zackery and Nouraei, Reference Demneh, Zackery and Nouraei2023; Gáspár, Reference Gáspár2023), illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Results of the horizon scanning structured using PESTEL framework (Source: Authors).

5.2. Identifying critical uncertainties

Drawing from horizon scanning, during the scenario building workshop, participants have identified several pivotal uncertainties. One of the foremost concerns is the “decision to return to Ukraine.” Participants expressed significant uncertainty about this choice. One participant (ES#2) stated:

I still do not know if I will come back. When I answer different surveys, I say ‘yes’, I want to come back… But it really is more complicated. I think about my kids and their future, and the truth is I am not sure.

Another critical uncertainty revolves around “the status of the war.” The unresolved nature of the war significantly impacts perceptions of safety and the feasibility of returning to Ukraine. This uncertainty extends beyond the war’s conclusion to encompass the resolution of dangers such as landmines and broader security concerns, especially regarding children’s well-being. A participant (ES#6) commented:

[…] Ok so the war is over, we come back, and we are afraid to go to the forest, sea because of the mines… I will always be worried when my kids go camping or travel… what if they find one of those mines… and environmental pollution… Will anyone ever clean all this? I am not sure.

The potential “extension or non-extension of the EU Temporary Protection Directive” introduces another layer of uncertainty. This uncertainty influences the legal and security landscape for displaced Ukrainians and their decisions regarding stability and future. A participant (ES#10) mentioned, “It depends if they [the EU] let us stay… what if they kick us out when the permit is over. Thus, we must have several plans…”

“Relations considerations” add complexity to decision-making processes. Relationship dynamics, such as the status of a partner remaining in Ukraine, whether divorced or not, and the presence of family members, especially children, contribute to this complexity. One participant (ES#1) shared, “It is horrible to say but thanks to the war I experienced what it is to live without him [husband] and I just cannot imagine how I can return to those violent relationships”. Another participant (ES#16) added, “What we will see is a pandemic of divorces. It is difficult to maintain a long-distance relationship, and between peace and war even more. They [husbands] are changing, we are changing to the point of no return…”.

Other factors affecting decisions include considerations of “children’s well-being.” Education, healthcare, and overall children’s well-being were often mentioned by the participants. A participant (ES# 9) noted, “The teachers are so nice here. In Ukraine, in public school, they just scream at kids and here the educational system is so kind I like it…But my kids say they like their school in Ukraine better”. Another participant added (ES#14) “The public health system is really working here. I am not sure what will be with the health system in Ukraine after the war…”

A pivotal uncertainty concerning the varying “levels of energy” among displaced Ukrainians to actively contribute to the development of their homeland was also mentioned. This uncertainty encompasses different levels of motivation, skills, and mental well-being. Participant discussions around the energy to contribute to recovery were extensive. One participant in their 40s from Kharkiv (ES#6) mentioned, “I don’t think I have any energy to deal with my life. My house was bombed, my friends are dead, and I will not come back to Kharkiv again. It is just a dark place for me”. Meanwhile, another participant from Kharkiv also in her 40s stated (ES#16):

Of course, I want to return and rebuild the country. This is the only possible way. My life has a meaning this way. In Ukraine, I can do so much, and here… they have everything here. Why would I put energy here?

Lastly, the “availability of suitable employment opportunities” represents another key uncertainty influencing return migration decisions. Prospects of meaningful job opportunities play a crucial role in individuals’ decisions regarding their return to Ukraine and are closely tied to their current employment status. An unemployed participant (ES#2) remarked, “In Ukraine, I can realize my ambitions, and here I can get a simple job and earn minimum wage. It all depends”. Another unemployed participant (ES#17) added, “I agree, but do you think about the past of Ukraine? Do you think you will be able to realize your ambitions in post-war Ukraine? I think we have more good employment options here”.

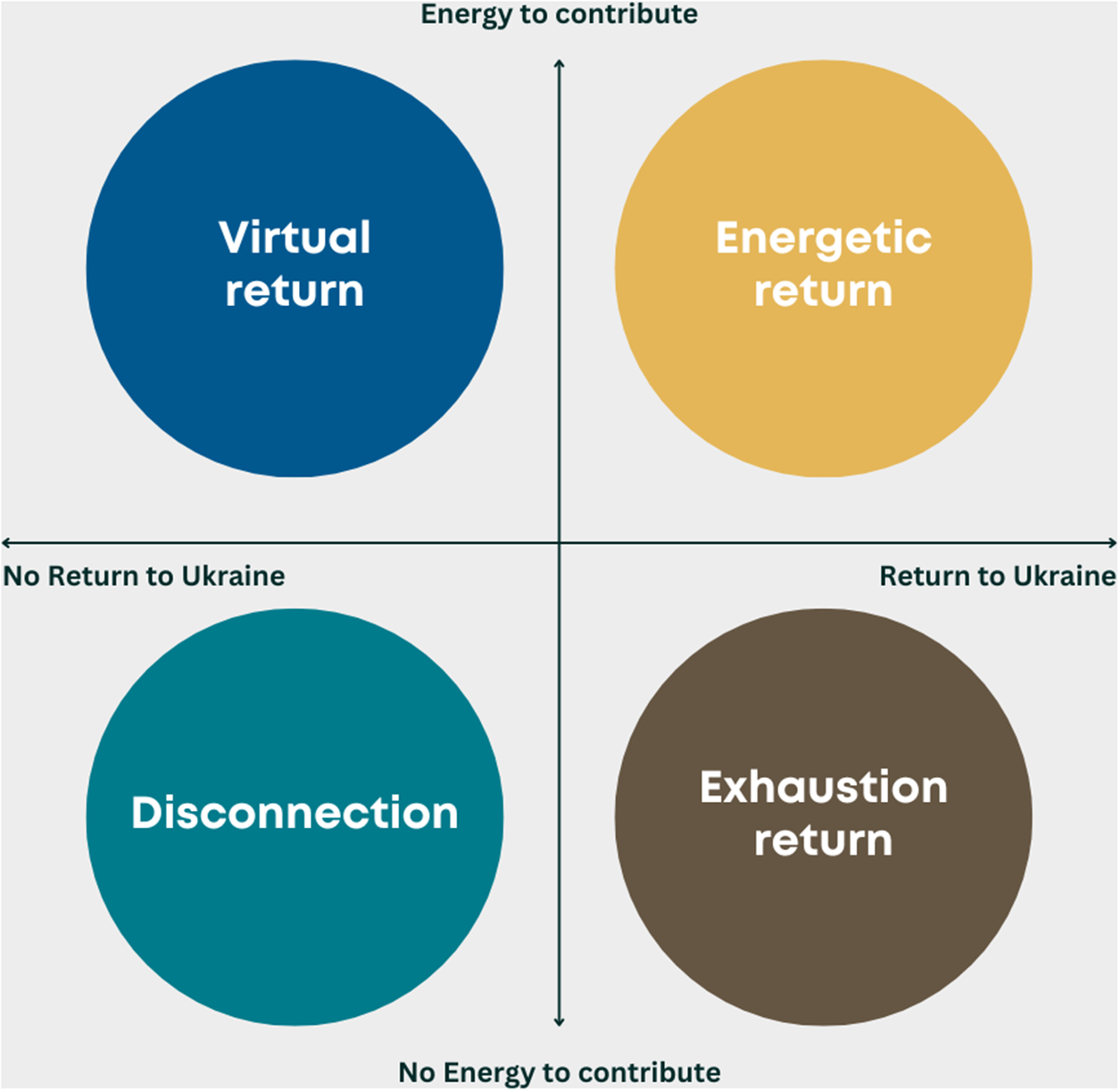

Based on these insights, participants selected two uncertainties—the decision to return or not and energy levels—to construct four distinct scenarios: virtual return, return with motivation, return with exhaustion, and disconnection (as named by the participants).

5.3. Developing future scenarios

Scenario-building as a crucial part of our foresight, helped us to collectively envision potential futures. In this section, we present four scenarios for Ukrainian return migration, developed by the participants, each depicting a distinct trajectory shaped by energy and return aspirations (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Scenarios for Ukrainian return migration (Source: Authors).

Firstly, in the “Virtual Return scenario,” a modest number of displaced Ukrainians choose to return to Ukraine. The majority, however, decide to stay abroad. Their decision is influenced by a preference to contribute remotely to Ukraine’s reconstruction efforts from outside the country, mainly due to worries about children’s future. This includes leveraging their expertise and energy, such as working remotely for Ukrainian municipalities, companies, and government, meanwhile taking care of children. This trend is shaped by global shifts, notably the widespread adoption of virtual collaboration platforms and the rise of digital humanitarian initiatives.

Beyond tangible contributions, displaced Ukrainians yearn for their experiences to be acknowledged. They seek validation and aim to overcome the stigma and trauma associated with leaving their homeland. Consequently, they are consulted about Ukraine’s future through surveys, petitions, and other participatory means. As one participant (ES#4) expressed, “In Ukraine, they always speak about how to get us back, as if we were some kind of property. But no one asks us how we feel, to what conditions we would like to return.”

Looking ahead, participants envision a technologically enriched landscape where digital platforms play a pivotal role in transnational collaborations. Tools like virtual reality hubs and augmented reality interfaces become commonplace for remote contributions. The rise of blockchain technology ensures secure and transparent cross-border transactions, fostering a global network for virtual contributors. “Ukraine is great with digitalization. I believe if they [the government of Ukraine] can expand a digital platform like DREAMFootnote 1, we could all easily take part in the Ukraine’s recovery” was mentioned by the participant (ES#19).

However, potential challenges such as digital equity concerns and potential disconnection from Ukraine’s cultural and social fabric were also identified. “I am worried that not all will be able to join such a platform. Like my mother. She knows how to use Facebook and Viber and that is all “was commented on by the participant (ES#4). “I am worried that we can actually become not relevant to modern Ukraine” was added by the other participant (ES#18).

In the “Energetic Return scenario,” a substantial number of displaced Ukrainians choose to return to their homeland with a robust desire to contribute to its recovery. Actively engaging in various reconstruction projects, they collaborate effectively with local initiatives and government programs. This scenario is underpinned by a general need for trauma healing, where contributing to Ukraine’s recovery becomes a therapeutic act, providing returnees with a profound sense of purpose and empowerment. “For me, returning home and being part of the reconstruction will work as medicine” was commented by the participant (ES#1).

As participants envisioned the future, they imagined grassroots empowerment movements, community-driven initiatives, and innovative start-ups. These embody various facets of social remittance, encompassing European values like gender equality, environmental protection, and linguistic diversity. For instance, a participant in her 20s (ES#15) mentioned:

For example, I am now in the Plast Organization here, and many things we do are to prepare our return and reconstruction of Ukraine. I am also studying here, and everything I learn I would like to implement in Ukraine. I think there are many young people like me.

Continuous diplomacy strengthens connections with Europe, shaping a vision that transcends mere return, embracing aspects like transnational war tourism: “I want to return and start a war tourism company. Lots of my friends from here would love to come and see all the places of sadness and our victory” was mentioned by one participant (ES#11). This scenario paints a vivid picture of a revitalized Ukraine, where displaced Ukrainians actively contribute to shaping the country’s trajectory towards something that participants viewed as “a harmonious and sustainable,” “technological,” “innovative,” “digital,” “skyrocketing economic growth,” “green,” “slow life,” “caring,” and “connected to Europe” future. However, challenges may arise in balancing those diverse perspectives. Moreover, ensuring the sustained momentum of these efforts, supporting this energy with enabling institutions, policies, and financing mechanisms, and aligning them with broader societal goals will be crucial for maintaining a positive trajectory.

In the “Disconnection scenario,” a limited number of displaced Ukrainians decide to return to Ukraine, while the majority opt to stay abroad. This choice is driven by fear, stigma, and societal pressure associated with their migration decisions. These apprehensions, particularly for men, create significant barriers to their engagement in reconstruction efforts.

“They see me as a betrayer. And I do see myself like this. I left to protect my family. But I did not protect my country. I do not think I will ever be able to come back” was commented by the male participant (ES#19) during the interview.

The scenario portrays a future where a segment of the diaspora remains disconnected, hindering active participation in Ukraine’s recovery. Overcoming societal biases and fostering open dialogues were recognized as imperative by the participants to encourage engagement and address challenges posed by fear and stigma. Nurturing a sense of belonging among those who stay abroad will be pivotal for creating a more inclusive approach to Ukraine’s reconstruction. The future calls for a comprehensive and empathetic strategy that fosters unity and understanding among all displaced Ukrainians, regardless of their chosen paths.

Lastly, in the “Exhaustion Return scenario,” a significant number of displaced Ukrainians decide to return to Ukraine, albeit with limited energy to actively contribute to the recovery. The return is primarily due to economic struggle, exhaustion, and mental health issues. Many may return because they could not find stable employment, learn the language, or adjust to the new culture in Europe, or due to the non-prolongation of the Temporary Protection Directive.

This return is not entirely voluntary and can be followed by a period of sadness, hence the constrained energy to contribute to the recovery.

“If I return this is because I did not manage to put roots here. Because I want to stay with my kid here. I see my future here. We are divorced [husband in Ukraine]. Nothing holds me there. But I still haven’t found a job here. It is difficult to take care of kids and learn languages, find a job, all without family support. And it scares me…” was stated by the female respondent (ES#16) during the interviews.

Envisaging this future, economic and mental health support systems become integral to the reintegration process. Workplace environments and community networks adapt to recognize the importance of mental well-being in sustaining long-term contributions.

The scenario foresees a future where the return journey becomes an opportunity for personal renewal, and support systems evolve to meet the nuanced needs of individuals navigating the complexities of return migration. However, there is a need to address potential challenges, including the risk of societal neglect and the potential burden on mental health support systems. Striking a balance between societal transformation and individual well-being will be crucial.

5.4. Drawing policy implication for the scenarios

The foresight scenarios offer policymakers a rich spectrum of considerations, each presenting a unique narrative on the potential trajectories of return migration. To enhance this exercise, we have combined these foresight scenarios with literature reviews to develop possible policy implications for each scenario.

The “Virtual Return scenario” encourages Ukrainian decision-makers to consider policies that cater to the evolving nature of modern migration. Rather than focusing solely on facilitating the return of all individuals and planning for full-scale return, a more nuanced approach is suggested. This approach accommodates varying aspirations, including meaningful participation without physically returning. Policymakers could acknowledge the transformative role of digital platforms in contemporary governance (Luna-Reyes and Gil-Garcia, Reference Luna-Reyes and Gil-Garcia2014; Kok and Rogers, Reference Kok and Rogers2016). Insights from displaced Ukrainians on how such platforms can meet their needs can inform the design of inclusive and effective digital systems. These policies align with studies emphasizing the role of digital tools in diaspora engagement (Gamlen, Reference Gamlen2014).

In crafting policies for displaced Ukrainians residing in EU countries, it’s essential to embrace the concept of dual intentionality, recognizing their simultaneous connections to both their home country and their host nation (OECD, 2023). This necessitates the development of inclusive frameworks that support integration into the host community while facilitating ongoing engagement with Ukraine. Policies could also strive to accommodate the dual intentions of displaced Ukrainians by establishing dual legal and taxation systems that enable them to maintain ties with their homeland while participating fully in the economic and social life of their host country.

In the “Energetic Return scenario,” Ukrainian policy interventions can leverage insights from the existing literature on the traditional return migration (reintegration of returnees) (De Bree et al., Reference De Bree, Tine and De Haas2010). For example, financial incentives, such as relocation grants, tax benefits, and temporary financial support, are identified as key facilitators for encouraging return (Bakewell, Reference Bakewell2014). To capitalize on the energy to contribute to recovery in line with international best practices, comprehensive programs that encourage active participation, entrepreneurship, and leadership among returnees through grants, training, and mentorship initiatives were proved to be useful (Dustmann and Mestres, Reference Dustmann and Mestres2010; Levitt and Lamba-Nieves, Reference Levitt and Lamba-Nieves2011). Furthermore, it is essential to balance diverse perspectives, conflicting views on development trajectories, and expectations within the returning community (Vargas-Silva and Boccagni, Reference Vargas-Silva and Boccagni2023). Finally, inspired by the case of Senegalese male returnees (Strijbosch, Mazzucato, and Brunotte, Reference Strijbosch, Mazzucato and Brunotte2023), adopting effective strategies to actively counter migration stigma is imperative.

From the EU perspective, it is imperative to create programs that facilitate the return and reintegration of Ukrainian migrants who no longer wish to stay in Europe, while also incorporating lessons learned from past failures (Kusari and Walsh, Reference Kusari and Walsh2021; Lietaert, Reference Lietaert2022; Moraru, Reference Moraru and Tsourdi2022). The EU can collaborate with Ukrainian authorities to develop comprehensive reintegration programs that address the unique needs and challenges faced by returnees (Meiners, Reference Meiners2024). Additionally, EU countries can offer support through grants and mentorship programs aimed at facilitating entrepreneurship and leadership among returning Ukrainians (OECD, 2023). By investing in such programs, the EU can ensure a smooth transition for migrants returning to their home countries and support their successful reintegration into society.

In the Disconnection scenario, policies addressing fears, stigma, societal pressures, and psychological aspects are required. Implementing communication strategies can play a crucial role in reshaping public perceptions and breaking down stigmas associated with those who choose to stay abroad. To counter barriers that hinder active participation in Ukraine’s recovery, policymakers can adopt measures to nurture a sense of belonging among those who stay abroad. Existing studies on diaspora engagement (Gamlen, Reference Gamlen2014) emphasize the importance of inclusive policies that recognize and value the contributions of individuals remaining outside their home country. At the same time, recognizing and respecting choices of disconnection could be important.

From the EU, this means recognition that many Ukrainians will stay and thus, policies promoting long-term integration may be more beneficial for both displaced and host societies, as demonstrated in the case of Norway. By investing in the long-term integration of displaced Ukrainians, the EU can reduce economic vulnerability and increase opportunities for their participation in the host society (Tyldum et al., Reference Tyldum, Kjeøy and Lillevik2023).

Within the “Exhaustion Return scenario,” insights from the third strand of existing literature on return migration (reintegration of returnees) will also be useful (De Bree et al., Reference De Bree, Tine and De Haas2010). Considering the unique circumstances surrounding the returnees in this scenario, flexible reintegration programs accommodating diverse experiences and circumstances are crucial. Ukrainian policymakers could prioritize the establishment of mental health support systems, integrate into the reintegration process, offering accessible and stigma-free mental health services for returnees (Laban et al., Reference Laban, Gernaat, Komproe, Tweel and Jong2006). Previous studies also showed that community networks play a crucial role in providing social support and understanding mental health challenges. Policymakers could facilitate the establishment of such networks, engaging returnees in community-building activities to foster a sense of belonging and reduce the risk of societal neglect (Porter and Haslam, Reference Porter and Haslam2005).

Similarly, from the EU perspective, creating programs to facilitate the return and reintegration of migrants who no longer wish to stay in Europe remains vital, giving specific attention to establishing mental health support systems. Collaboration with Ukrainian authorities to develop comprehensive reintegration programs tailored to the unique needs and challenges of returnees in this scenario is imperative. By investing in such initiatives, the EU can support the successful reintegration of migrants returning to their home countries, regardless of the reasons behind their decision to return.

6. Discussion

6.1. Beyond one-size-fits-all: building scenarios for anticipatory governance

This collective exploration into the potential trajectories of Ukrainian return migration amidst the ongoing Russian invasion reveals a multifaceted tapestry of uncertainties and potential scenarios of the (return) migration futures, departing from the conventional linear narrative of return or not to return.

Our findings align with a study on pre-war Ukrainian returning migrants, which identified two main groups: the ‘Disappointed’ returning due to disillusionment with their life abroad, and the “Missioners” achieving financial goals or completing missions (Ivaschenko-Stadnik, Reference Ivaschenko-Stadnik2013). Interestingly, parallels can be drawn between these categories and our identified scenarios of Exhaustion and Energetic return. However, our study introduces a novel dimension of “energy to reconstruct,” coined by the participants, which is deeply connected to the realities imposed by the ongoing war.

While contemporary displaced Ukrainians may face certain familiar aspirations and challenges akin to those experienced by past returning migrants, it is crucial to recognize the novel and intricate dynamics introduced by the current circumstances, as highlighted by the participants thought the participatory process: renewed sense of patriotism, the growing importance of digitalization, feminized nature of current migration, changing family dynamics, experiences of trauma, mental health disorders and stigma especially for men, and all this in connection to the desire/energy to contribute to the Ukraine’ reconstruction.

Despite these new challenges, there is still much to be learned from past experiences, particularly regarding the reintegration challenges faced by previous Ukrainian labor migrants. These challenges encompassed legal, social, and psychological complexities, including documentation hurdles, loss of parental roles, discrimination, loneliness, and cultural shock (Ivaschenko-Stadnik, Reference Ivaschenko-Stadnik2013). In the current context, these challenges are compounded by the urgent need for addressing stigma, navigating digital platforms for information and support, engaging in reconstruction efforts, and adopting a gender-sensitive approach to migration policies among others.

In essence, while recognizing the importance of drawing insights from the historical migration dynamics in Ukraine, it’s crucial to acknowledge the evolving nature of the current context. The novel challenges encountered by displaced Ukrainians demand a nuanced understanding, which our study facilitated through horizon scanning, identification of critical uncertainties, and collective scenario construction.

The scenarios in particular offer policymakers a structured nuanced understanding of the diverse future paths that return migration envisioned. Each scenario, from the Energetic Return to the Disconnection, provides a comprehensive narrative that encapsulates the varying motivations, challenges, and aspirations of the displaced Ukrainians. It is evident that a one-size-fits-all policy solution would fall short in addressing the multifaceted nature of futures of the return migration (McAdam, Reference McAdam2012; Scholten, Reference Scholten2020; Mencutek, Reference Mencutek2022).

This echoes the recognition that policies demand flexibility (Hines and Bishop, Reference Hines and Bishop2020). In essence, our foresight exercise enhances the comprehensive conceptualization of policy preparedness, aligning with what Guston (Reference Guston2014) describes as anticipatory governance. It aims not to predict the future with certainty but to develop the capacity to anticipate and respond effectively to a spectrum of potential futures. This exercise prompts policymakers to adopt a forward-thinking mindset, echoing Sweeney’s (Reference Sweeney2017) perspective that foresight is about preparing for multiple plausible futures, not predicting a singular predetermined outcome. Policymakers are advised to view the scenarios and identified signals, trends, critical uncertainty and so on, to bolster strategic agility and responsiveness, enabling dynamic policy adaptation to evolving circumstances.

Foresight, as demonstrated in this study, plays a crucial role in this adaptability by identifying multiple scenarios and various aspects of potential futures, contributing to a more dynamic and responsive policy framework (Hines and Bishop, Reference Hines and Bishop2020). However, it is essential to acknowledge that while these scenarios offer valuable insights, they do not fully capture the breadth of opinions, aspirations, needs, and lived experiences, age, class, gender and other intersectionality of displaced Ukrainians. A more comprehensive exploration would entail delving deeper into the complexities of migration dynamics, yielding a broader array of exploratory futures and scenarios. While such an endeavor cannot definitively predict the future, it can significantly enhance the futureproofing of migration policies. Building upon the foundation laid by this study, further participatory engagement and broader exercises would yield even more comprehensive and nuanced insights.

6.2. The participatory nature of the foresight and its implication

The participatory aspect of the foresight methodology employed in this study, involving Ukrainian displaced in Spain, adds a unique dimension by actively engaging the displaced population in shaping the discourse around their return and contributing to the development of their homeland. It also ensures that these scenarios are not just theoretical constructs but reflections of the lived experiences and perspectives of those intimately familiar with the complexities of migration, displacement, and return.

Participants brought a unique perspective to foresight discussions. For instance, the identification of critical uncertainties, such as the level of energy to contribute, introduces an emotionally charged dimension. This aspect, highlighted by participants, played a pivotal role in constructing entirely different scenarios, challenging the conventional narrative of simple return versus not return. Additionally, elements like strained relationships with partners left in Ukraine (divorce or not) or the escalating stigma for those who left Ukraine are deeply rooted in displaced daily encounters and societal pressures, offering insights that may be overlooked in expert-driven trends. This is something that Zúñiga and Hernández-León (Reference Zúñiga and Hernández-León2005) describe as experiential knowledge that delves into the emotional and psychological dimensions of knowledge, aspects challenging for experts to fully grasp.

These emergent themes provide policymakers with an emotional backdrop, offering nuanced insights that extend beyond statistical analyses. Recognizing the impact of stigma and trauma, gender aspects, addressing critical uncertainties, and navigating conflicting views are essential considerations for decision-makers in crafting migration policies that are not only effective but also sensitive to the diverse and complex realities of those affected by migration dynamics. Moreover, it’s imperative to consider the gender dimensions of these policies, acknowledging the unique challenges faced by women and men, particularly concerning caregiving responsibilities and gender-based discrimination, as was shown in this and similar studies (Blomqvist, Reference Blomqvist2023; Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Isański, Nowak, Sereda, Vacroux and Vakhitova2023).

The participatory foresight undertaken in this study addresses a critical gap in migration studies where displaced experiences often find themselves eclipsed by narratives constructed by experts and policymakers (Cordero-Guzmán et al., Reference Cordero-Guzmán, Martin, Quiroz-Becerra and Theodore2008; Sheller and Urry, Reference Sheller and Urry2006). This commitment to dismantling the hegemony of knowledge aims to provide a platform for displaced Ukrainians to actively shape their narratives and influence the unfolding events. As we navigated through participatory foresight, the diverse perspectives of the Ukrainian displaced resonated with the notion that displaced are active agents, not passive subjects, in migration (OECD, 2020). Centering their insights emphasizes not only the significance of recognizing these experiences but also the potential for the displaced to play pivotal roles in shaping the reconstruction of Ukraine.

The four scenarios developed in our study should not be perceived as isolated policy recommendations but rather as narratives that illuminate different facets of the complex landscape surrounding return migration. Drawing inspiration from the works of scholars like Hines and Bishop (Reference Hines and Bishop2020), we emphasize that the primary value lies in the process of envisioning and understanding these scenarios collectively with the affected community. This collective imagination aids in unveiling implicit assumptions, revealing blind spots, and fostering a holistic perspective.

7. Conclusion

In this collective exploration of potential trajectories for Ukrainian return migration amidst the ongoing Russian invasion, we revealed a multifaceted migration landscape marked by uncertainties and complexities. From myriad weak signals, critical uncertainties, and scenarios, we uncovered nuanced narratives that underscore the imperative need for flexible and anticipatory migration policy solutions. These range from, for example, facilitating a smooth return to Ukraine for those wishing to do so, to supporting digital infrastructure for “virtual return” options.

The participatory nature of our foresight methodology, engaging Ukrainians displaced in Spain, marks an important contribution to the migration studies. By centering on the experiences of the displaced, we ensure that scenarios are not merely theoretical constructs but reflections of lived experiences, offering a unique vantage point that adds to the expert projections. This approach, grounded in the socio-cultural complexities and emotional journeys of the displaced, provides new knowledge and nuances to reshape Ukraine’s return migration policies.

Our discussion on policy implications aligns with the study’s broader objective of translating theoretical exercises into real-world impact. The participatory foresight approach has the potential to reshape migration policies, setting precedents for inclusive, forward-thinking migration governance. By emphasizing social intelligence and including the displaced narrative, policymakers can craft data-driven yet people-centered policies. Participation becomes the bridge between the world of experts and the lived experiences of displaced people in the ever-evolving migration landscape. Embracing displaced unique insights and foresight collectively navigates the complex terrain of Ukrainian return migration, offering more inclusive, effective, and holistic solutions.

In conclusion, this research underscores the dynamic and complex nature of return migration, emphasizing the need for policies that are not only flexible and anticipatory but also inclusive and considerate of the diverse experiences and aspirations of those affected by migration dynamics. The participatory foresight approach emerges as a powerful tool, bridging the gap between expert-driven narratives and the lived experiences of displaced people, enriching the discourse on anticipatory and inclusive migration governance.

While the study conducted in Valencia, Spain, provides valuable insights, limitations shape directions for future research. The focus on Valencia restricts generalizability, prompting the need for comparative studies exploring return migration dynamics in various host countries. The small sample size in Valencia may not fully represent the diversity and intersectionality within the displaced Ukrainian community, advocating for larger and more diverse participant groups in future studies. Moreover, the study does not deeply explore challenges in implementing recommended policies, opening avenues for research into the feasibility and potential drivers and barriers to effective policy implementation. In essence, this study serves as an exploration and a steppingstone, inviting further studies into the complex dynamics of return migration and the collaborative construction of inclusive policies that resonate with the diverse realities of displaced populations.

Data availability statement

Authors can offer more comprehensive details regarding the materials utilized upon a reasonable request. However, complete interviews and transcriptions cannot be shared due to confidentiality issues.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the study participants for the time and knowledge shared with us.

Author contribution

O.U.: Conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. R.M-D.: Investigation, visualization, and writing—review and editing.

Funding statement

This research was possible thanks to the support from the Spanish State Research Agency (CSIC) under the International Cooperation Plan with Ukraine and through the JAE Intro 2023 grant.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.