Introduction

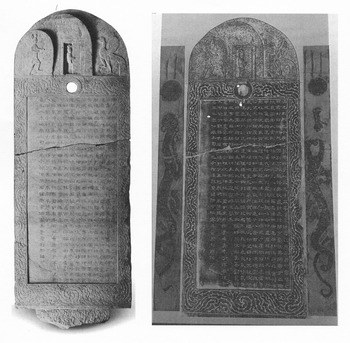

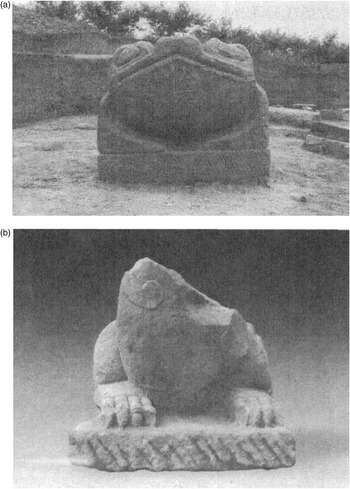

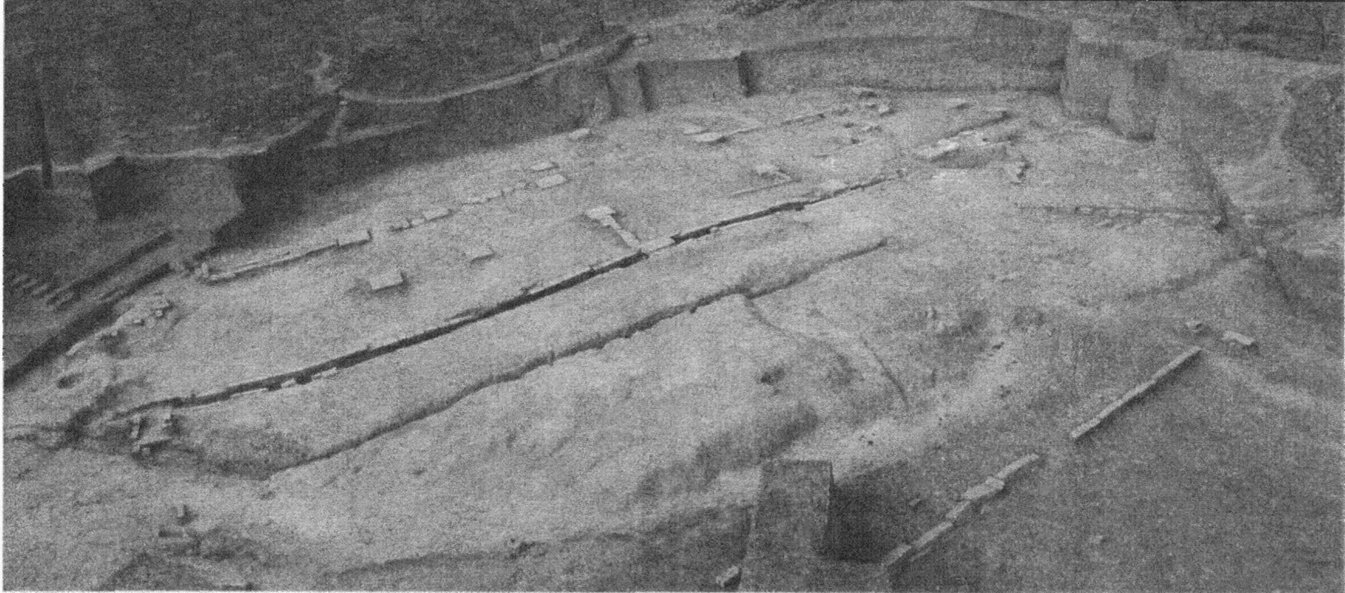

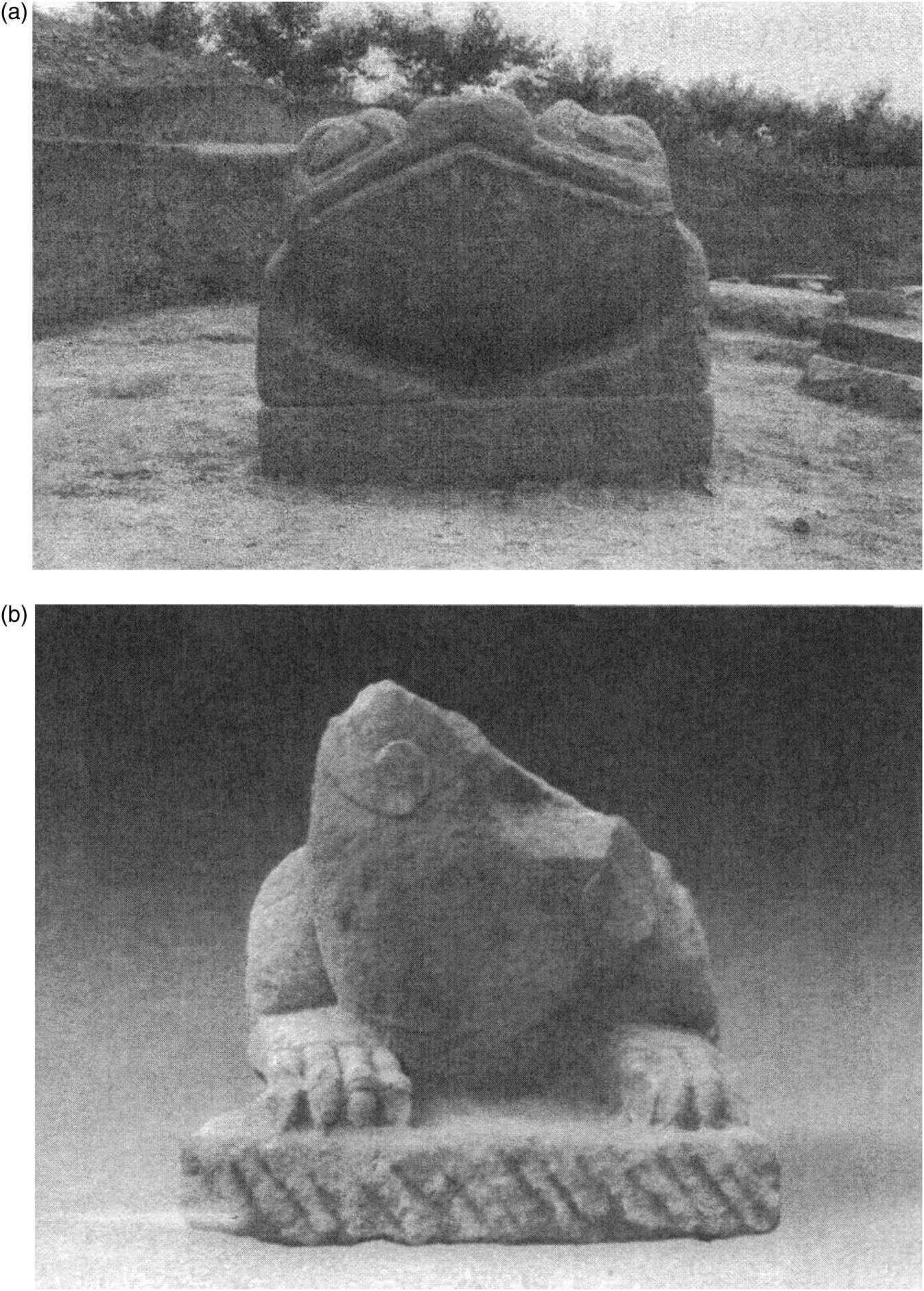

In March 2004, archaeologists working prior to the flooding of the Three Gorges region on the Yangtze River in Jianmin village 建民村, Yunyang county 雲陽縣 in Chongqing Municipality, unearthed a stele dated to 173 ce and dedicated to Quren county 胊忍縣 magistrate Jing Yun 景雲, who died 70 years earlier in 103 ce. Given the title “Stele for the Han dynasty Ba commandery Quren county magistrate Jing Yun” (漢巴郡朐忍令景雲碑) by scholars, it is now housed in the Chongqing China Three Gorges Museum (Figure 1). The stele's unusual relief carving and its inscription, which appears to borrow from one of the oldest anthologies of Chinese verse, the Chuci 楚辭, make it a fascinating artefact that tells us much about the south-west in early imperial times. It was discovered next to a rammed-earth building platform with four animal-shaped stone plinths partially preserved and contemporaneous with the stele itself.Footnote 2 The archaeological report of the excavation site, known as the Jiuxianping platform 旧縣平臺, shows the remains of a fairly well preserved large architectural structure that possibly served as part of a protective building where the stele was placed for public view. The site also contains remains of a house foundation, channels for water drainage, and a wall, suggesting that it was an established building complex at the timeFootnote 3 (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1. Stele for the Han dynasty Ba commandery Quren county Magistrate Jing Yun and its rubbing (Source: Photo by author)

Figure 2. Excavation site at Yunyang county, Chongqing municipality (Source: Jilin Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology and Yunyang Prefectural Office of the Preservation of Cultural Relics, “Chongqing Yunyang jiuxian ping taiji jianzhu fajue jianbao”, 23)

Figure 3. Remains of animal-shaped stone plinths from the excavation site at Yunyang county, Chongqing Municipality (Source: Jilin Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology and Yunyang Prefectural Office of the Preservation of Cultural Relics, “Chongqing Yunyang jiuxian ping taiji jianzhu fajue jianbao”, 25)

The stele is made of red sandstone and comprises a head, a body, and a stand, the latter heavily damaged and mostly missing. In its current state it is 220 cm high and 137.5 cm wide. It contains an inscription of 13 lines with a total of 367 characters carved on the obverse of the stele. The head of the stele bears a complex decoration in high relief carving which is singular in content and a rare instance on monuments of this type. The reverse of the stele, where we would expect to find the names of those who had commissioned and financed the making of the stele, is left plain and undecorated. Thus, apart from the commemorative text, Jing Yun's stele does not contain a donors’ list.

Eastern Han dynasty stelae are generally carved with a decorative border that envelopes the main calligraphic inscription which may extend to both sides of the monument. In some cases the head of the stele bears a simple carved image, such as the bird seen on the stele erected for the “filial and incorrupt” (xiaolian 孝廉) official Liu Min 柳敏 (fl. 146 ce), or a dragon coiled around the title carved on the head of the stele made for Ba commandery 巴郡 governor Fan Min 樊敏 dated to 205 ce.Footnote 4 Complex decorations, such as those seen on Jing Yun's stele, remain exceptionally rare. Overall, the stele is impressive for its size, its deeply carved composite decoration, and for its calligraphy that is skilfully executed in the clerical script.

The location where Jing Yun's stele was discovered is noteworthy. Yunyang county was the ancient site of Quren county, which is recorded in the Hanshu as one of the 11 counties belonging to Ba commandery.Footnote 5 The Huayang guo zhi 華陽國志 (Records of the Kingdoms South of Mount Hua) compiled by Chang Qu 常璩 (c. 291–361 ce), mentions Quren being famous for its ale, Lingshou trees 靈壽木, oranges, salt wells, and numinous turtles (ling gui 靈龜). The wells of the local Tang Spring 湯溪 are said to have produced salt rocks as large as one square cun.Footnote 6 The county is also listed in the Shuijing zhu 水經註 (Commentary on the Classic of Waterways), compiled by Li Daoyuan 李道原 (d. 527 ce), which records the establishment of the earliest official Salt Bureau (yanguan 鹽官) in Ba commandery, in 118 bce. This bureau administered over 100 salt wells in the region.Footnote 7 From these sources we know that Quren was a county of considerable wealth and abundant natural resources which made it one of the most prosperous territories in the south-west.

Stelae form an integral part of the physical make-up of the south-west's landscape. The etymological dictionary, the Shiming 釋名, compiled by Liu Xi 劉熙 (d. c. 219 ce), advises how stelae emerged as a primary symbolic form with a funerary or commemorative function from the early Eastern Han period.Footnote 8 They served as locators, but more importantly, they were monuments made for public scrutiny and were thus placed in strategic positions where they were visible for all to see.Footnote 9

Eastern Han stelae may be divided into two categories: those that were made for funerary purposes to honour the deceased and the family's ancestry are known as mubei 墓碑, mortuary or ancestral stelae. This type of stele connected chamber tombs built underground with monuments erected above ground. Wu Hung describes how a Han burial site was marked by a tumulus above the tomb. The beginning of the spirit path (shendao 神道) that led to the tumulus was first made visible by a pair of gate towers (que 闕). Visitors or family members of the deceased would embark on the spirit path that guided them through the gate towers, after which they encountered a number of stone sculptures in the form of guardian animals and figures. Following the path, they were further directed to one or two stelae erected in front of an ancestral shrine (zongmiao 宗廟), with the tumulus behind it.Footnote 10 The tomb, where sacrifices were offered, functioned primarily to serve the family; however, mubei were intended as public statements erected for everyone to see. Made of stone and incised with calligraphy, they customarily documented information on the deceased's ancestry and lineage, his or her achievements, and perhaps most importantly, stated why the person merited remembrance. Information on the stele was often repeated on the que that accompanied it, and at times inside the tomb as well. In summary, the function of the mubei confirms that the burial complex during the Eastern Han period was a shared space belonging to both private and public domains. Designed to benefit the dead as well as the living, mubei represented a synthesis of funerary and social memorial.

The second group of stelae were made for the general public to commemorate a person's meritorious deeds and to uphold a model citizen for society and later generations to follow. These are known as jishi bei 紀事碑, songde bei 頌德碑 or commemorative stelae.Footnote 11 The majority of extant commemorative stelae were erected for men, although a very small number were also made to honour women. Commemorative stelae were generally commissioned and financed by local officials or friends, colleagues and subordinates of the dedicatee, indicated by a list of donors’ names that was usually placed on the reverse of the stelae. They were erected in a public space that was often linked to the person's meritorious services.

There is some debate among Chinese scholars over the nature of Jing Yun's stele. Cheng Diyu argues that the language of the inscription, which contains an extensive expression of mourning, is of a funerary nature and that the stele is therefore a mubei. However, the stele was not discovered at a cemetery site nor was it commissioned by any of the Jing family members. It was made on the orders of the Quren magistrate Yong Zhi 雍陟 to commemorate Jing Yun for his meritorious services to the county.Footnote 12 As the stele only mentions Yong Zhi's name as dedicator, it is likely that it was primarily commissioned and financed by him. Kenneth Brashier confirms the stele's commemorative nature and suggests that it was intended to pay homage to someone who had become a local deity-like figure in people's memories. Although the stele offers one of the longest and most evocative images of public remembrance for a local prefect, nevertheless, it was made as an outdoor monument for public consumption and not a carefully preserved text kept within the household.Footnote 13

Since its discovery, Jing Yun's stele has been studied by a number of Chinese and Japanese scholars who have provided annotations of its inscription, but have not analysed the nature and structure of its language, nor sought to explain the iconography of the carved decoration and its relevance to the text below it.Footnote 14 Brashier mentions the stele in both of his works, Ancestral Memory in Early China and Public Memory in Early China, observing how the text typically borrowed lines and formats from earlier classical literature with the aim of celebrating Jing Yun's achievements.Footnote 15 He recognizes the stele's importance in early China's commemorative culture but notes how little detail is supplied and suggests that the text is restricted by a Confucian rhetoric that merely serves to foster and preserve public memory.Footnote 16

Following an examination of the iconography of the decoration on the head of the stele, this paper provides a full translation, annotation, and analysis of the inscription and for the first time establishes the link between the complex message conveyed in the decoration and the text. Second, it places the stele in its historical context and considers the possible reasons behind its commissioning 70 years after Jing Yun's death. Another aspect examined is the language and literary style of the stele's eulogy which appears to have borrowed from the poetic tradition of the Chuci. Central themes of lament and some of the more eclectic concepts of the sacred expressed in the songs and poems of the Chuci are evident in the text of the stele. The paper argues that the stele shows how people in the south-west were not only familiar with the poems of the Chuci, but valued it as a text closely linked to their cultural heritage.Footnote 17

Relief decoration on Jing Yun's stele

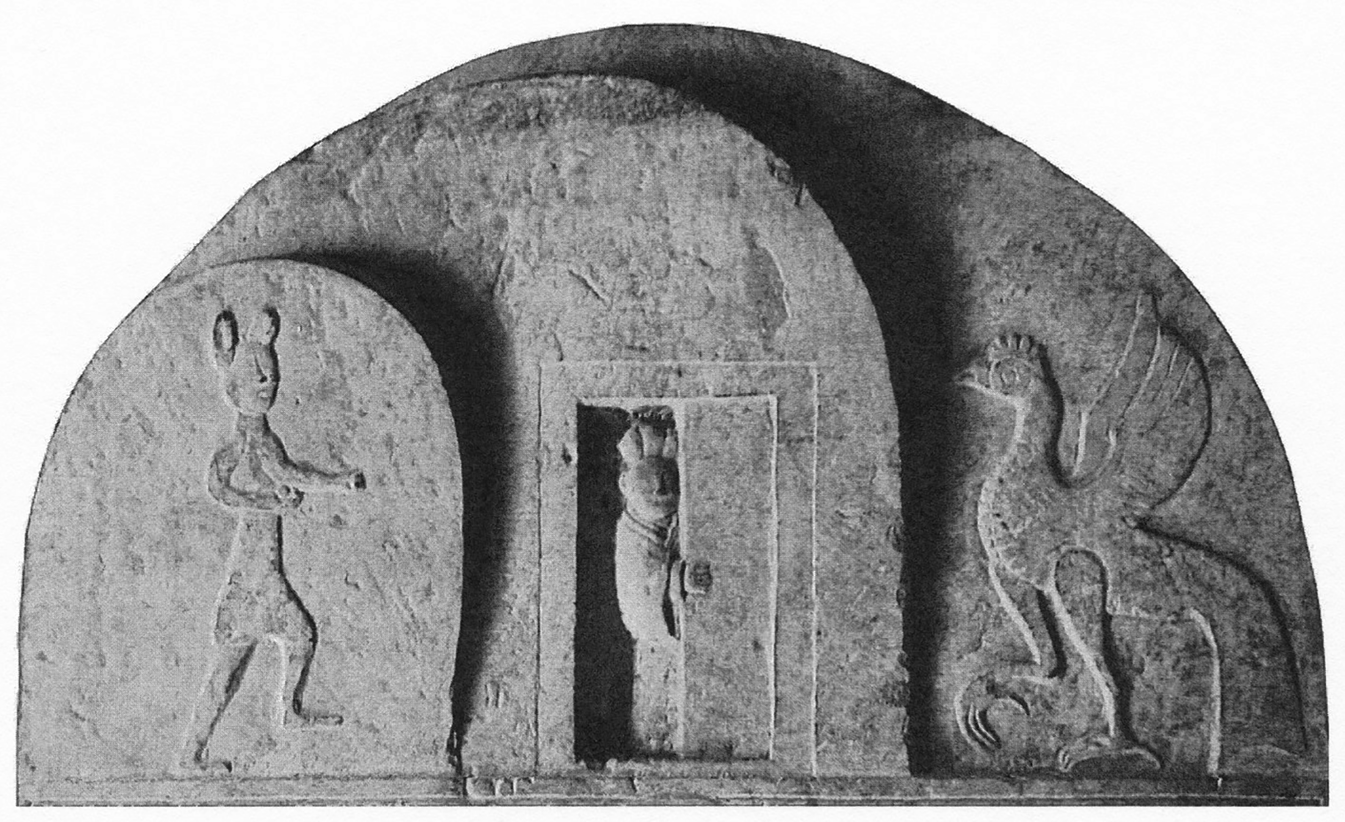

The head of the stele is carved in relief with three images in separately defined arches which may represent mountains, associated with the notion of the sacred mountain in Eastern Han tomb art, or are simply of a decorative form (Figure 4).Footnote 18

Figure 4. Detail of the head of the “Stele for the Han dynasty Ba commandery Quren county magistrate Jing Yun” (Photo by author)

On the left we see a tall figure with a pair of ears pointing upwards from the crown of its head, suggesting that we are looking at a celestial immortal being, generally referred to as xian 仙, but also known as the feathered or winged people (yuren 羽人), the latter named for the feathers often depicted on their backs.Footnote 19 The xian on the stele displays all the characteristics of Han-period depictions of an immortal, with striking ears and foreign-like facial features such as a prominent nose that distinguishes it from ordinary humans. He Xilin suggests that its portrayal could have originated from the Chu culture, influenced by the practices of prolonging life that were gradually becoming popular in Chu society during the middle and late Warring-States period.Footnote 20 The connection between the xian and Chu is significant and shall be explored later in the paper.

The xian on Jing Yun's stele is shown with arms stretched in a gesture of offering. In its right hand it is holding a small round object that appears to be the pill of immortality (Figure 5). The figure has been also identified as the “Jade Rabbit” (Yutu 玉兔), possibly because of its large rabbit-like ears and this mythical creature's association with making the elixir of immortality. However, in the tomb art of the south-west the Yutu is customarily depicted in the company of Xiwangmu 西王母, in the form of a rabbit squatting on its haunches, holding a pestle and mortar as it pounds the drug of immortality, and not as a standing human figure.Footnote 21

Figure 5. Details of carving on the head of stele (Photo by author)

A similar xian to that on the stele is described in the Han poem, preserved in the Yuefu shiji 樂府詩集, titled “Song of a Long Journey” (Changge xing 長歌行):

仙人騎白鹿, 發短耳何長. 導我上太華, 攬芝獲赤幢. 来到主人門,

奉藥一玉箱. 主人服此藥, 身體日康强, 發白復更黑, 延年壽命長.

The immortal is mounted on a white deer. Oh how short is his hair! How long are his ears! He shall lead us to the Supreme Floral Heaven, in order for us to grasp the lingzhi and receive the red banner.Footnote 22 He shall come to the gate of the master, bringing drugs in a jade casket. If the master ingests this drug, his body shall grow healthier and stronger every day. His white hair shall once more turn black, and he shall prolong his years and gain longevity.Footnote 23

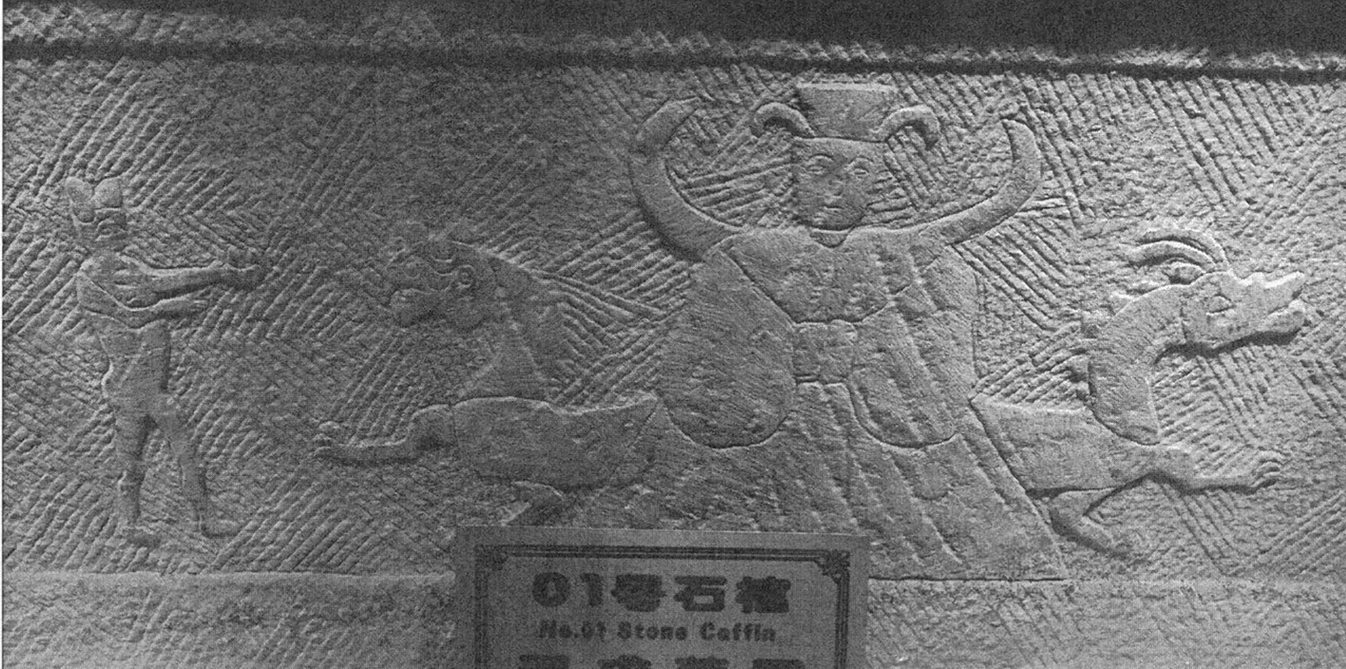

This image of a xian is also closely related to that found on a stone sarcophagus from a cliff tomb at Zhangjiagou 張家沟 in Hejiang county, Sichuan province, where an immortal (also with large ears) is shown holding a round pill in a similar gesture of offering to Xiwangmu seated on her dragon and tiger throne. Scholars have given the pictorial scene on the sarcophagus the title “Picture of [Hou] Yi Seeking the Medicine [of Immortality]” (Yi qiu yao tu 羿求藥圖), with the immortal identified as the mythical archer Hou Yi 后羿, who was gifted the pill of immortalityFootnote 24 (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Section of stone sarcophagi with “Picture of Hou Yi seeking the medicine of immortality” (Photo by author)

In early legends Hou Yi was not given the pill by Xiwangmu but by the Gods, nor is he depicted as a xian but as a human archer on contemporaneous tomb art from the Central Plains of China.Footnote 25 Given this, notwithstanding the identification of the figure on the sarcophagus as the archer Hou Yi, we may simply be looking at a xian rather than the mythological figure of Hou Yi specifically. The xian images on the stele and on the sarcophagus from Hejiang are characteristic of the south-west, where stories and characters were adapted to suit local culture and decorative traditions.

Regarding the role of these immortals, He Xilin notes how both visual and textual evidence show them serving as the aid or guide to transcendence and also as bestowing the drug of immortality.Footnote 26 Robert Campany describes xian as the individual who sought to become a transcendent, a god-like being with supernormal powers. This quest for transcendence became a major form of religious expression by the late Eastern Han period and helped lay the foundation for the growth of the Way of the Celestial Masters (Tianshi dao 天師道), the first Daoist movement founded by Zhang Daoling which established itself in the south-west. Campany, in his examination of the role of the xian, argues that the quest to become xian-like or a holy person in society became a social phenomenon, and practitioners were not isolated xian-hood seekers but gained considerable reputations as holy people.Footnote 27 We shall return later in the paper to the notion of Jing Yun's representation as a god-like figure in the text of the stele.

In tomb art xian are usually depicted in the company of other creatures, such as dragons, tigers, deer, and birds – propitious animals associated with its supernatural powers.Footnote 28 Such is the function of the Vermilion Bird (zhuque 朱雀) carved on the right arch of the head of the stele. The Vermilion Bird presides over the southern quadrant and symbolizes the yang principle of brightness, light, and heat.Footnote 29 It is also linked to the Daoist alchemical and physiological practices as referenced by Wang Yi 王逸 (fl. 114–119 ce) in his commentary to “Wandering far away” (Yuanyou 遠游) (“Yuanyou” hereafter) in the Chuci. The poem reads, “I pointed to the God of Fire and we galloped straight toward him. I was on my way to the Southern Doubts. Seeing the vastness of the world beyond my homeland, I let myself float as though on open seas” (指炎神而直馳兮, 吾將往乎南疑. 覽方外之荒忽兮, 沛罔象而自浮).Footnote 30 In his commentary, Wang Yi notes on these lines that the “God of Fire” is the quintessence of the “True Mercury” of the Vermilion Bird of the southern region. Thus, he treats this passage as a virtual manual of alchemical technique with its references to the particulars of the elixir of immortality.Footnote 31 The “Yuanyou” had much in common with the Daoist cult of the immortals and is labelled as the earliest youxian 遊仙 (wandering immortals or wandering amongst immortals) genre of poems which depict journeys into the realm of the immortals.Footnote 32

The Vermilion Bird features regularly on decorated stone sarcophagi from the south-west, frequently depicted in the company of the physician Bian Que 扁鵲 (c. 401–310 bce).Footnote 33 For example, Bian Que, in the form of a xian (with a human body and large pointed ears) is shown receiving the medicine herb from the Vermilion Bird on a stone sarcophagus unearthed from a cliff tomb at Hejiang county.Footnote 34 The portrayal of Bian Que, the Vermilion Bird, and the medicine plant on the sarcophagus represents an equivalent iconography to that on Jing Yun's stele where the plant was substituted by the pill of immortality (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Section from a stone sarcophagus with “Picture of Bian Que and the Vermilion Bird” (Photo by author)

The central arch on the stele is rendered with the image of a half-open door with a figure standing on the threshold peeking out between the two door-leaves. This image is primarily found in a funerary context in Han art and is explained by scholars as representing an entrance to another, invisible space.Footnote 35 The door is always half open with the other half firmly shut, at times with a figure shown peeking out, but may also be found merely as a half-open door with no-one behind it. It is an image that is highly suggestive yet at the same time enigmatic. It invites speculation about the role of the mysterious person, what the image symbolizes, and where the half-open door was thought to lead. Fei Deng suggests that the scene is about the possibility of entering the realm where celestial beings existed, and that the door can be seen as a means of access into that otherworld.Footnote 36 Just as with the Vermilion Bird, a passage from the “Yuanyou” may be relevant to our understanding of the half-open door image. In the poem the author wishes to follow the famous Daoist immortal, Wang Qiao 王喬 saying, “Drifting on a mild southern breeze, I arrive at South Nest to spend the night. Where Master Wang with open doors receives me. And I sought from him the secret of primordial energy” (順凱風以從游兮, 至南巢而壹息. 見王子而宿之兮, 審壹氣之和德).Footnote 37 The poet laments his wasted years and his incapacity to play a role in government and decides to move on and to take Wang, a successful transcendent, as his model. Devoting himself to various esoteric practices, he is finally able to visit Wang's spiritual domain in the south and receive instructions on nurturing the vital breath from the legendary master himself.Footnote 38 The description of Master Wang receiving the poet into his mythical world so that he can become a free spiritual being in the “Yuanyou” seems very like the image of the half-open door with the figure behind it on the stele. The image may even be, given the other links between the stele and the “Yuanyou” explored later in the paper, a reference to this passage from the poem itself.

The two sides of the stele are carved with the images of the Azure Dragon (Qinglong 青龍), the guardian of the East with the Sun above its head on the left, and the White Tiger (Baihu 白虎), the guardian of the West with the Moon above its head on the right. The two beasts respectively represent the yang and yin opposition and interaction. In tomb art they are generally symbols of protection, placed near the tomb entrance to guard against ghosts and evil spirits. Together they communicate the wish to ward off evil. A further relevant meaning to the stele is the symbolism represented by the joining of the dragon and tiger suggested by the phrase “the way of not dying” (不死之道). This phrase is explained in the Hanfeizi 韓非子 where we read about the King of Yan 燕王 and his passionate pursuit of immortality.Footnote 39

In summary, the iconography of the carved decoration on the head and sides of the stele may be explained as the imagined sequence of journey or transcendence into a paradisiacal sphere, located behind the half-open door, aided by the propitious forces of the xian, the Vermilion Bird, and the pill of immortality. Help is also obtained from the combined forces of the tiger and dragon. The ability to embark on a distant journey for the transformation of one's state of being was thought possible through the consumption of elixirs that became the main objectives of the theme of “distant journeys” reflected in the poems and songs of the Chuci. Footnote 40 We read in the “Yuanyou” how the poet “followed the Winged People to the Cinnabar Hills, and stayed in the old country of the Undying” (仍羽人於丹丘兮, 留不死之舊鄉), with the Winged People portrayed by the xian and the Cinnabar Hill, their abode, located behind the half-open door on the stele.Footnote 41

Although the various decorative elements found on the head of Jing Yun's stele are not unique to the south-west and, as is the case with the iconography of the half-open door which was readily employed in the tomb art of north China, there is nevertheless a connection between the images of the xian, the half-open door, and the Vermilion Bird and the Chuci, in particular the poem “Yuanyou”.Footnote 42 While the themes of a journey and that of immortality are reflected in the pictorial carving, we find references to sorrow and lament – ideas that are pivotal to the songs and poems of the Chuci – expressed in the inscription of the stele which will be explored following the translation of its text below.

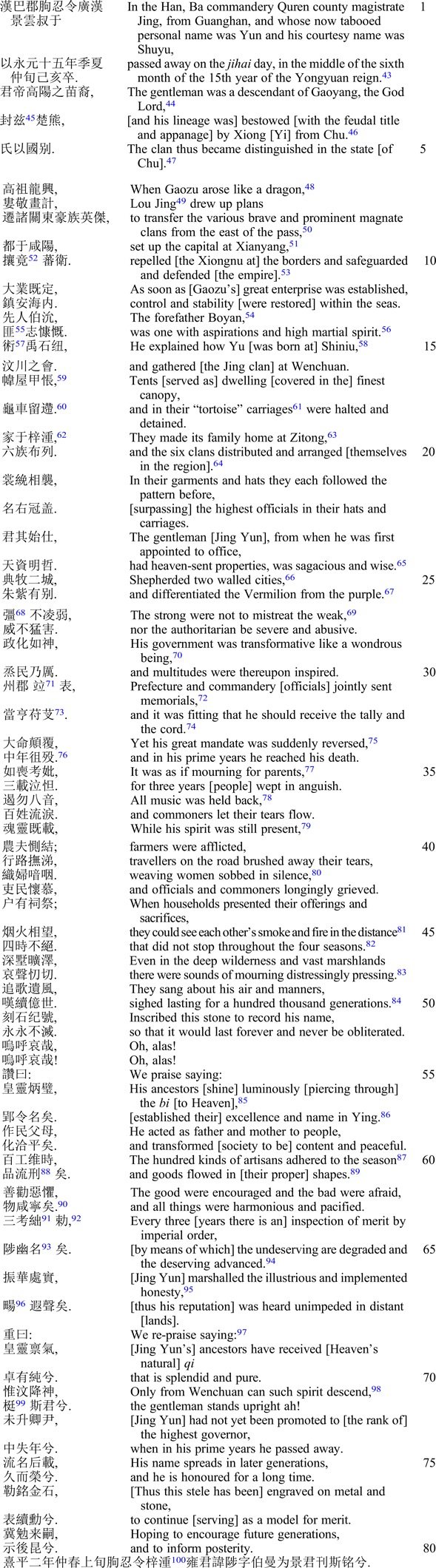

Translation of the inscription on Jing Yun’s stele

This stele was carved for gentleman Jing by the Quren county magistrate, gentleman Yong from Zitong, whose now-tabooed personal name is Zhi, and his courtesy name is Baiman, in the beginning of the second month of Spring, in the second year of the Xiling reign (173 ce).Footnote 101

Commentary on the text

The text on the stele may be divided into three parts: a preface (lines 1–22), a biography of Jing Yun in the form of an extended eulogy (lines 23–54); and a post-script (lines 55–80) which consists of two distinct sections (lines 55–67 and 68–80). The preface provides a precise placing of the dedicatee, a technique used in stelae inscriptions to position the person in local memorial culture.Footnote 102 In giving an account of Jing Yun's ancestors, the third line of the text directly borrows from the poem “On encountering sorrow” (Lisao 離騷) (“Lisao” hereafter), from the Chuci, quoting “descendant of Emperor Gaoyang the God Lord” (帝高陽之苗裔).Footnote 103 These opening lines stress the clan's imperial southern heritage and record their eminent status within the state of Chu prior to the establishment of the Han dynasty.

During the reign of Emperor Gaozu (r. 202–195 bce), the clan moved away from their homeland of Chu and settled down in Guanghan commandery, making their family home in Zitong, located in present-day Sichuan province (lines 8–12). There is no specific mention of the reasons behind the clan's relocation, except for the region being described as the birthplace of Yu the Great and as such a location deemed worthy of settlement (lines 13–18). However, the text mentions Lou Jing, political advisor to Gaozu and initiator of policies that were subsequently implemented by the Han government (lines 8–12). Lou's political, social, and military strategies, as the text notes, made a significant contribution to the stability of the empire (line 12). Lou recommended moving the powerful magnate clans (haozu 豪族) to the metropolitan area, known as the Guanzhong 關中 region, so that the government could keep them under surveillance and control. This reference to Lou on the stele serves as an explanation for the transfer of the Jing clan from Chu.Footnote 104 It accords with the recordings of the Hanshu which lists the Jings amongst the five major clans from the state of Chu who were transferred during the reign of Gaozu.Footnote 105 The clan's prominence in the south-west continued as they benefitted from an eminent status in society (lines 21–22), retaining their customary dress code and enjoying the same elevated position as the local officials of rank and status. Asserting Shiniu in the south-west as Yu's birthplace also claims a weighty role for the region. More than twenty sites throughout China are mentioned as the birthplace of Yu in classical literature and reference to it became a trope to indicate an elevated status for a locality.Footnote 106

Reference to Lou Jing in the text also suggests that his policies had a significance for the stele's dedicator, Yong Zhi.Footnote 107 The Hou Hanshu mentions the promotion of Yong Zhi to the governorship of Yizhou commandery sometime between 173 and 176 ce.Footnote 108 We know of his position as Quren county magistrate, prior to taking up the position of governorship, only from the stele. This period in the south-west's history, especially the region of Yizhou commandery (located in present-day Yunnnan province), was characterized by continuous unrest amongst the ethnic population who rebelled in large numbers against the Han military forces.Footnote 109 Yong Zhi was captured in 176 ce when Yizhou fell into the hands of the rebels. The Han government was only able to regain control of the region and save him from the rebel forces when they allied with the Bandun 板楯 ethnic people from Ba commandery and introduced a more relaxed and compassionate policy towards the region's population.Footnote 110 Although not yet posted to Yizhou at the time of erecting the stele in 173 ce, Yong Zhi may have been already aware of the counterproductive nature of the Han Empire's confrontational occupation of the border territories and the futility of endless warfare. Drawing attention to Lou's pacifying policies towards the Xiongnu over three centuries earlier may have served as an example and model for bringing peace and stability to the south-west and avoiding further military conflict.Footnote 111 With the erection of the stele he may have wished to emphasize lessons learnt from past events for the sake of current and future policies.

Following the preface, the text elaborates on Jing Yun's deity-like qualities and how he became an inspiration to the people and officials in the region (lines 24–28). Regrettably, he met with an untimely death in his prime that prevented him from enjoying recognition and the promotion he deserved (lines 31–34). A further parallel with the “Lisao” may be drawn here. The “Lisao” focuses on the sociopolitical aspects of human life and describes the existence of a pure and devoted official amidst a world of injustice where his lofty aspirations remain unfulfilled. It also articulates an honest official's inner conflict, the contradiction between the urge to escape into a pure and ideal realm on the one hand and a deeply engrained feeling of moral responsibility to work for the good in the human world on the other.Footnote 112 Jing Yun may be seen as the pure and devoted official who, although prevented from reaching the path of success he deserved, was able to achieve a state of transcendence and became a local cult figure with deity-like qualities. Yong Zhi may have considered Jing Yun as a model, seeing himself also as a dutiful official with a governance responsibility but not able to pursue his personal ambitions and spiritual fulfilment in the world surrounding him. The themes of lament in the text and the depiction of spiritual journey in the relief carving on the head of the stele were relevant to Jing Yun's life but also to Yong Zhi himself.

The opening lines of the “Yuanyou” may give us a further insight into Yong Zhi's predicament. It reads, “Grieving at a dead end in a degenerate time, I wished to be weightless, to ascend and wander far away, But with no such power among my feeble gifts, What would I ride to float to the sky?” (悲時俗之近阨兮, 願輕舉而遠遊. 質菲薄而無因兮, 焉託乘而上浮?).Footnote 113 Gopal Sukhu in his analysis of this passage suggests that it provides an image where the spirit of the main persona wanders through another dimension, the spirit world that, in the modern view, could be seen as a combination of internal and external reality.Footnote 114 Perhaps Yong Zhi wished to become xian-like in the footsteps of his predecessor, Jing Yun, who continued to live in public memory 70 years after his death. Yong Zhi's predicament is reflected in the juxtaposition of two worlds, the world of the xian and that of men as expressed in the stele.

Jing Yun's memorialization as a god-like figure should also be understood in the context of the Chu culture as described by Wang Yi in his commentary:

昔楚國南郢之邑, 沅湘之間, 其俗信鬼而好祠. 其祠必作歌樂鼓舞以樂諸神. 屈原放逐竄伏其域, 懷憂苦毒愁思沸鬱. 出見俗人祭祀之禮歌舞之樂.

In the old days the people of Chu who lived in the area around the old southern capital and the lands lying between the rivers Yuan and Xiang, were a superstitious folk much addicted to a kind of religious rite in which they entertained various gods with singing, drumming and dancing. After his banishment, when Qu Yuan was living in hiding in this area, he would sometimes emerge to seek distraction from the burden of grief and care which oppressed him by observing the villagers at these rustic festivals, singing and dancing to delight the gods.Footnote 115

Sukhu, in his examination of the Chuci and images of Chu during the Eastern Han period, notes how Chu culture, with its preoccupation with the worlds of the shamans and spirits, came to be criticized by the old Confucian literati – the group with which the Han Reformists most closely identified and who took a strongly anti-Chu and anti-shamanistic stand in their political ideals.Footnote 116 The so-called “Chu mode”, reflected in the Chuci, thus came to be associated with a culture perceived to be barbarian that had no place amongst the literary circles of the Eastern Han court, yet as we see from Jing Yun's stele, not only survived, but was preserved in the literature and political rhetoric of the south-west.

Regarding the south-west's economy, the text mentions how Jing Yun ensured that the “hundred kinds of artisans adhered to the season and goods flowed in their proper shapes” (lines 60–61). Considering that he was in charge of two walled cities (line 25) and the general prosperity of the county, mentioned earlier, we can assume that the success of his governance fostered the manufacture of quality goods. Apart from the south-west's economic wealth we are also given an insight into how officials were advanced or degraded following an inspection of merit every three years (lines 64–65) and the extent of power held by county officials, such as Jing Yun, who appear to have had considerable influence in these matters (line 66). The final section of the text reiterates the reasons for the erection of the stele, reminding us how Jing Yun's name and achievements might serve as a model and are transmitted and preserved for the future (lines 77–80).

Text and its relation to the Chuci

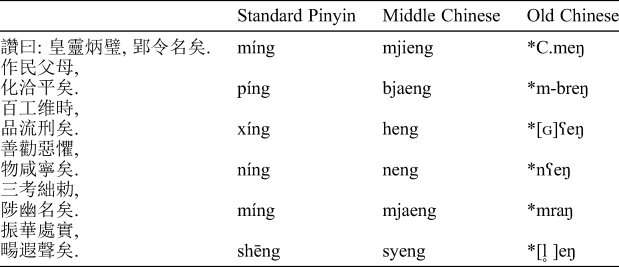

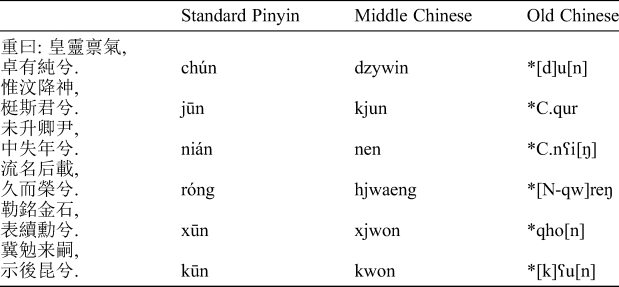

We have already seen connections with the Chuci in the pictorial images of the xian, Vermilion Bird, and the half open-door. There is a further parallel between the narrator of the “Yuanyou” as a wearied official longing for spiritual transcendence and the stele's text. Further links with the Chuci, in particular the “Yuanyou”, can be found when we examine the language and structure of the text. The purpose of this paper is not to provide commentary on the the “Yuanyou” itself, which is already much discussed, but to highlight its influence on the text of the stele. Paul Kroll notes how the “Yuanyou” is constructed from a series of vignettes and shifts in topic or action that divide the long composition into sections and notes how sometimes these sections correspond with changes in rhyme.Footnote 117 The same technique is employed in the post-script of the stele which is divided into two distinct sections that are differentiated by changes in rhyme. The first section (lines 55–67) employs the sentential marker yi 矣, with every word before yi rhyming with ming 名 in the first couplet. Due to phonetic changes in the Chinese language over time it is not always easy to hear these rhymes, thus they are clarified in Table 1.

Table 1 Pronunciation of rhyming characters before the marker yi in Standard Pinyin, Middle Chinese, and Old Chinese

The second section (lines 68 to 80) employs the rhythmic particle and pause marker xi 兮 with the words before xi rhyming in every pair of couplets, as shown in Table 2.Footnote 118

Table 2 Pronunciation of rhyming characters before the marker xi in Standard Pinyin, Middle Chinese, and Old Chinese

The use of rhyme and markers, such as yi and xi, in the text highlights the climax of the lament and suggests a familiarity with the rhyming mode of the Chuci. The function of xi in the Chuci was meant to be musical. This technique displays a familiarity with the rhyming mode of the Chuci that regularly employs markers such as the xi, which is placed at the end of each line with the rhyme taking place in the last word before it. The function of xi in the Chuci was meant to be musical, since it does not have a meaning except as an indication of emphasis as a drawn out sound of a sigh or an “ah” in modern Chinese.Footnote 119 The inclusion of poetic rhyming in the stele's text suggests that these passages may have been chanted when read. As mentioned earlier, shamanistic chants and invocations supplied much of the stimulus for the songs of the Chuci. Kroll notes how the placement of musical interludes in the “Yuanyou” may have been intended to produce a sense of euphoria equivalent to the rapt trance of the shaman and allowed the poet to break free of all bounds.Footnote 120

The language of mourning in the text is also reiterated with the use of the phrase “we re-praise saying” (zhongyue 重曰), that creates an additional unit following the customary eulogy presented by the phrase “we praise saying” (zanyue 讚曰). The two sections of the post-script, analysed above, are introduced into the text with the phrases zangyue and zhongyue respectively. The “Yuanyou” utilizes zhongyue as a formal link to an additional section in the poem which repeats the poet's lament for aspirations beyond his reach.Footnote 121 The adoption of recursive forms that reiterate or turn back upon themselves, suggesting a conscious reflection on an emotion, is examined by Douglas Hofstadter who suggests that recursions help induce a mental state in which the mind has the ability to move up to a higher level of comprehension.Footnote 122 Hofstadter finds examples of this approach in music and in literary works, thus it is not surprising that we see the same in the poetic craft of the “Yuanyou” and similarly in Jing Yun's stele. As we can see, the text in Jing Yun's stele employs two distinct poetic techniques from the Chuci, in particular from the “Yuanyou”, that confirm a familiarity with the anthology. The use of rhyming schemes of this kind are exceptional on stelae.

Conclusion

Amongst Eastern Han commemorative stelae from the south-west, Jing Yun's monument stands out for its carved decoration, calligraphy, and for the content of its inscription. It represents important documentary and material evidence for the study of local and regional history. Furthermore, it appears to incorporate literary and cultural references from the southern anthology, the Chuci. There is an emphasis on the heritage of the state of Chu and its culture in the description of the ancestry of the Jing clan and in the language of praise for Jing Yun who became a god-like figure in society. Studies on the Chu culture note the importance of deity worship and how people made extensive use of sacrificial rites of singing and dancing which distinguished it from other cultures, especially those of north China and the Central Plains.Footnote 123

Alongside the eulogy and accounts of mourning, there are specific references to society, the economy and governorship. These narrations, which were created for specific local purposes, reflect society's wish to record events or certain individuals for the preservation of memories that are continually shaped to fit the needs and circumstances of the moment.Footnote 124 While we can only speculate on the intentions behind the erection of the stele, it is likely, given the tumultuous conditions of the south-west in the Han empire at this time, that the text's deliberation on the past was included because it was seen as relevant to the contemporary context of the challenge in governing a border territory at a time of political and military unrest.

The pictorial imagery on the head of the stele provides a further clue to the dedicator's possible objectives. The carved decoration and the text below it represent two distinct spheres – the former the mythical terrain of the xian immortals, the latter the ephemeral and transient nature of life lived and mourned after death. The tension between the two spheres is captured in the persona of the narrator of the “Yuanyou”, who laments his burden of official duties and longs for spiritual journeying. This poem may well also have inspired the stele, imbued as it is with quotations from and imitations of the poem's literary style, as well as containing images which also relate closely to it.

The stele also gives us an insight into a number of events that are informative and remain worthy of our examination. For example, we read about the nature of the relocation of notable clans from the former state of Chu, their settling in the south-west territories and the prominence of the memory of this heritage many centuries after the settlement; the training and selection of local officials; the importance of artisans and the production of goods to the region's economy; and in general, the process of how officials were memorialized by colleagues in early China.

The stele reveals the influence of the cultural heritage of the Jing clan in the south-west and of how the language, vocabulary and rhyming system of the Chuci was preserved, transferred and used in its intellectual milieu. In the text we glimpse a society that celebrates an identity that is linked to the state and the culture of Chu, not only because of the Jing family's line of ancestry but also because that identity is lived in both the imagination and in texts. Poems such as the “Yuanyou” became a source of inspiration for its poetic idioms but perhaps, more importantly, for the themes of lament and its voicing of anguish with the transience and limitations of one's existence, all of which are expressed in the stele's text and images. The examination and interpretation of stelae remains a neglected field, possibly due to the challenges of deciphering their complex language and content; nevertheless, close study of these artefacts and their texts shows a depth of meaning and reveals their significance to our understanding of the period.