Social media has played an increasingly prominent role in recent conflicts – for instance, the 2010–11 uprisings in the Middle East, famously dubbed the ‘Twitter revolution’, the conflict between Israel and Hamas,Footnote 1 and even the civil war in Syria. Yet what do rebel organizations really gain from using social media? Prima facie, not much – aside, perhaps, from improved logistics. Rebel organizations face few constraints or costs in their use of social media, potentially reducing the perceived credibility of their messages, which leaves the impact of messages conveyed through this medium unclear.

We argue that rebel organizations use social media as a tool of public diplomacy – that is, an instrument to offer international audiences their own narrative of the conflict and to present themselves as a credible, preferable alternative to the existing government – through which they can gain international actors’ support. In civil wars, rebels often seek the aid of outside powers,Footnote 2 yet they typically lack the means to communicate directly with outside actors. Collecting original data, we find that rebel diplomacy via Twitter significantly increases co-operation with the rebels when their message: (1) clarifies the type of regime they intend to create and (2) emphasizes the atrocities perpetrated by the government. Several implications follow from our findings. First, social media enhances rebels’ ability to engage in ‘strategic moves’,Footnote 3 thereby increasing the likelihood that they will attract external co-operation through the use of public diplomacy. Secondly, social media plays an important role in leveling the playing field, by allowing non-state actors to compete with states to gain access to foreign audiences. Finally, in an increasingly connected international arena, the importance of public diplomacy continues to grow, even in civil wars, where its role may have previously been discounted.

The use of social media as a tool of rebel diplomacy fits into a long history of attempts by groups opposing the government to seek direct ways to communicate their agendas to potential supporters – an illustrious example is Thomas Paine’s ‘Common Sense’ pamphlet. Yet research in communication shows that Twitter is a particularly useful tool for rebels to project a favorable self-image. First, Twitter grants access to international audiences to an unprecedented degree: in March 2011, the first full month of the Libyan civil war, Twitter estimated that approximately one billion tweets were sent every week.Footnote 4 Secondly, it allows rebels to spread their message to an audience of diverse geographical (and even temporal) composition:Footnote 5 on average, each tweet reaches 1,000 users, including non-followers of that tweet’s source.Footnote 6 Thirdly, Twitter allows rebels to instantly disseminate their narrative of the conflict, thus overcoming the government’s traditional attempts to omit, delay and bias the rebels’ side of the story.Footnote 7 These characteristics make Twitter an especially useful tool for rebel public diplomacy, as it enables rebels to communicate their narrative of the conflict to a much larger foreign audience than would otherwise be possible. This in turn enhances their ability to mobilize foreign support for increased co-operation.

We first theorize the ways in which rebels can use social media as a tool of diplomacy. Because we are interested in uncovering social media’s impact on rebel diplomacy, we theorize and model the effects of rebel organizations’ social media usage, rather than study the effects of social media more broadly. Secondly, we analyze the 2011 civil war in Libya. We conclude by discussing the implications of our research.

REBEL COMMUNICATION AND DIPLOMACY IN CIVIL WAR

Rebel organizations typically operate at a material disadvantage relative to the government,Footnote 8 and thus seek external support, which is often pivotal in helping rebel organizations survive and attain a more favorable outcome.Footnote 9 Prevailing accounts of external support focus on structural factors of the conflict as determinants – for example, the rebels’ relative capacity, the regime type of the state, the involvement of rival outside powers, and existing kinship ties between rebels and outside states.Footnote 10 Less explored is rebels’ active role in securing outside support. This omission is all the more striking because rebels have usefully been theorized as behaving strategically in studies of other aspects of civil war – for example, targeting civiliansFootnote 11 or selectively spoiling peace agreements.Footnote 12

We argue that, just as in their selective use of violence, rebels are strategic actors that will endeavor to frame information for international audiences. In so doing, rebels engage in what Schelling calls a ‘strategic move’, which consists of attempting to shape the perceptions of potential interveners in such a way as to make greater co-operation with the rebels appear to be more beneficial.Footnote 13 In other words, we investigate rebels as agentic actors that seek to promote their own narrative of the conflict abroad in order to shape foreign perceptions of these structural factors. For example, to persuade potential interveners that supporting the rebels will not be too time intensive or resource consuming, rebels will portray themselves as strong and resolute, capable of defeating the government in short order with international support.

By focusing on rebel agency in attracting foreign support, we theorize that rebels will promote their own narrative of the conflict abroad by framing the conflict – that is, diffusing a specific account of the events on the ground. Through the strategic use of framing, rebels can mobilize support by shaping the cost–benefit calculations of the target.Footnote 14

In their efforts to shape third parties’ perceptions, diplomacy is a vital tool for rebels, as it allows them to portray themselves as a serious, credible alternative to the current government and thus worthy of foreign support. Much like states, rebels invest resources in diplomatic efforts, and sometimes even hire public relations firms or open political offices abroad.Footnote 15 However, they encounter a catch-22: traditional forms of diplomacy that are crucial for rebels to present an image of being worthy of statehood, such as sending diplomats abroad, are predicated on the assumption that actors engaging in diplomacy have the authority to issue laws and follow through on their commitments, yet rebel organizations do not meet those prerequisites precisely because they are not states.Footnote 16

In this context, Twitter is uniquely well suited for rebel public diplomacy – that is, for establishing a direct link of communication with foreign audiences in order to obtain their support.Footnote 17 On the one hand, Twitter works like other, traditional tools of public diplomacy (such as radio stations or pamphlets). It enables rebels to directly convey their own narrative of the conflict to foreign elites and publics. Indeed, foreign audiences are often interested in information about the conflict that is best gained from the rebels themselves, namely who the rebels are and what their objectives are in the conflict. Information of this kind influences the beliefs, perceptions and behavior of the recipients of this information, even though that information is relatively inexpensive to produce, and not readily verified – that is, cheap talk.Footnote 18

On the other hand, there are several characteristics that set Twitter apart from other tools of public diplomacy. First, it provides access to larger numbers of people than radio or other mediums, as rebels typically lack the infrastructure and distribution to disseminate their message on an equivalent scale to that afforded by Twitter. In 2011, the year of the Libyan civil war, Twitter had 100 million active users.Footnote 19 Secondly, the online technology allows it to reach a very geographically diverse audience. For example, Leetaru et al. find that the average distance between Twitter users who tweet a message and those who re-tweet it is 749 statute miles, suggesting that Twitter facilitates the transmission of messages between users across great distances.Footnote 20 Finally, in contrast to traditional methods of dissemination including pamphlets and radio broadcasts, Twitter allows rebels to instantly and directly reach foreign audiences.

Thus Twitter is an especially effective medium for rebel public diplomacy. Its unique social media features make it easier for potential supporters in foreign states (both elites and the masses) to access rebels’ information and narratives than would be the case with other communication mediums. By more directly exposing a larger audience to their narrative of the conflict, rebels may help mobilize larger coalitions to support their cause in foreign states. This is likely to be especially impactful precisely because elites tend to have an early monopoly on information about foreign conflicts.Footnote 21 By reducing barriers to distributing news about the conflict, rebels are able to reduce the information asymmetry between the public and the government. In turn, this allows rebels to counter anti-intervention messages from elites and bolster pro-intervention messages from elites. Moreover, because rebels can directly manage their message, they can circumvent the media fatigue and bias that may otherwise impede the dissemination of their ideas.

Therefore Twitter constitutes an important diplomatic tool for rebels, because it represents a communicative space in which the government’s classic structural advantage over the rebels does not necessarily apply. We now consider the mechanisms through which Twitter works, and the messages that rebels are likely to transmit.

Mechanisms: How Twitter Helps Rebels Gain International Support

Rebels use social media to gain direct access to foreign publics and elites in order to shape foreign perceptions of the conflict and thus increase co-operation from outside powers. Outside actors, however, are strategic, and weigh the costs and benefits of supporting rebels. However, factions often form within the decision-making elite between those who support getting involved in the conflict and those who oppose it; the outcome of the competition between these factions is shaped by the information available to them.Footnote 22 Divisions of this sort arise not only within government, but also outside it, for instance in elite circles such as the media, think tanks and academia. Therefore, rebel diplomacy can play an essential role in providing information to elite factions that are in favor of providing support. Two types of information are highly salient for foreign publics and elites when contemplating support for rebels: (1) the costs, in terms of time and resources, of intervention and (2) the potential benefits of a rebel victory.Footnote 23 Outside powers are more likely to intervene when they expect the costs to be relatively low and the benefits to be high. Rebels can use diplomacy via Twitter to address each of these concerns, thus engaging in strategic moves designed to shape the perceptions of major powers, analogous to social movements.Footnote 24

Twitter, like other tools of public diplomacy, works by allowing rebels to reach multiple audiences at once, both foreign publics and foreign leaders. This feature allows Twitter to work to the rebels’ advantage through two sets of reinforcing mechanisms, both of which are widely studied in analyses of the impact of social media on social movementsFootnote 25 and on government decision making.Footnote 26

The first set of mechanisms allows rebels to gain access to foreign narratives of the conflict. First, Twitter enables disintermediation, meaning that rebels can communicate their message without any media filtering.Footnote 27 This makes their communication effort less subject to ‘media fatigue’ and other forms of media bias that are the product of the economic and professional incentives that influence media coverage. Secondly, Twitter’s international reach allows rebels to engage in scale shifting – that is, elevating a local crisis to the international level, thus drawing direct and unfiltered international attention to the conflict and to their version of the events on the ground.Footnote 28 During the Libyan civil war, for instance, Twitter had a remarkable ‘megaphone effect’: links shared on Twitter attracted the attention of foreign citizens, news media and governments.Footnote 29

The second set of mechanisms through which Twitter usage operates builds on the first. Once rebels have penetrated foreign discussions of the conflict, Twitter allows them to strategically tailor their narrative of the conflict in order to increase foreign support for their cause at both the domestic and elite levels. First, Twitter allows rebels to frame the conflict – that is, to present their own narrative.Footnote 30 Previous work has found that communication efforts from foreign elites via US media can help shape US public opinion when they present rival narratives to those promulgated by US elites.Footnote 31 Such narratives are likely to be particularly impactful on public opinion when they highlight ‘focusing events’, such as dramatic violations of human rights on the part of the government. Indeed, public support for human rights in countries such as the United States may be strongly influenced by major contemporary events.Footnote 32 These focusing events place pressure on the governments of potential interveners to take action, a phenomenon widely recognized since the 1990s, when the so-called CNN effect motivated Secretary of State Albright to state that ‘because we live in a democratic society, none of us [in the Administration] can be oblivious to those pressures’.Footnote 33 Social media gives rebels the ability to exert this type of pressure with unprecedented directness, bypassing the media and elites. Indeed, Jo notes that multiple rebel organizations use Twitter to directly engage with international institutions such as the UN Human Rights Committee.Footnote 34 Third-party governments often feel compelled to respond and to explain their own actions (or lack thereof) during international crises, so much so that the offices of the US secretary of state routinely detail their foreign policies using tweets in 100 different languages.Footnote 35

Secondly, by allowing rebels to state their preferences and commitments publicly, Twitter helps them reduce the information asymmetry between foreign governments and their citizens. This makes it easier for factions supporting intervention in third parties to build a larger coalition. When support for policies such as intervening on the side of the rebels is based on information that elites have but the public does not, the public might be more likely to doubt the importance and feasibility of a pro-rebel intervention. As Colaresi demonstrates, ‘national security secrecy […] robs an executive of the democratic tools to credibly signal to the public […] that threatening or cooperative gestures are in the national rather than a leader’s private interest’.Footnote 36 Opposition to intervening on the side of the rebels often capitalizes on this type of information asymmetry by emphasizing how little is known about the rebels.Footnote 37 Thus public statements via Twitter are important for increasing support because they help pro-intervention factions within the elite make a stronger case for their position. This is the case because such statements publicly provide additional information, and therefore reduce the burden of demonstrating to the public that intervention will help save lives and protect human rights, rather than serve the narrow interests of government elites.

Finally, the rebels’ framing of the conflict on social media can provide supporters of the intervention abroad with talking points – that is, with informed and detailed commentaries and news on aspects of the conflict that the local government tries to hide from international audiences.Footnote 38 These talking points enhance the ability of foreign proponents of intervention to persuade their publics by presenting a coherent and uniform narrative in support of involvement in the civil war. This type of information is particularly important in civil wars, because information about events on the ground is typically scarce, as well as systematically biased in favor of the government – a fact that may hinder foreign audiences’ willingness to support rebels.Footnote 39

In sum, Twitter serves as an important tool of image projection as it is able to reach both foreign publics and leaders publicly. Specifically, it allows rebels to penetrate foreign discourses about the conflict (via disintermediation and scale shifting) and strengthen support for intervention at both the public and elite levels (via framing, reduction of information asymmetries and talking points).

Hypotheses: Linking Rebel Diplomacy to Potential Intervener Behavior

Potential interveners contemplate whether to support rebels using a strategic approach. States typically prefer to intervene when a successful intervention requires a modest amount of resources, and when the regime that the rebels propose to create after the war is likely to align more closely with its preferences than the existing regime. To evaluate these factors, potential interveners seek to gather information through traditional intelligence methods in the warring state. In this context, rebels’ public pronouncements can provide a missing piece of the puzzle: their own account of the conflict. This is particularly important because potential interveners perceive the costs and benefits differently, and as Western finds, factions often form within decision makers with different perceptions of those trade-offs. Rebels can frame the narrative of the conflict in a way that gives supporters of intervention more evidence to build on as they advocate supporting the rebels, and this can prove crucial.Footnote 40 As strategic actors, we expect rebels to tailor their message to appeal to the decision calculus of foreign publics and elites, which center on the expected costs and benefits of co-operation with the insurgents.

First, third parties measure the cost of military aid to rebels in terms of how long the outside party must remain involved in the conflict, and how many resources it must devote to the rebels in order to help them achieve victory.Footnote 41 Rebels can influence international beliefs about the costs of intervention by demonstrating that they are succeeding on the battlefield, in order to counteract government propaganda. They can use Twitter to bypass the government’s monopoly of information about the conflict and to communicate their strength on the battlefield to external audiences.

Hypothesis 1: Rebel pronouncements regarding their success and determination in the conflict will increase future co-operation from external actors.

Rebels can also influence international beliefs about the costs of intervention by demonstrating that they have the support of the international community, which will reduce the costs of providing aid in two ways: by legitimating aid to the rebels and by distributing the burden of supporting the rebels to multiple actors. Indeed, Coggins finds that great powers tend to coordinate their recognition of secessionist movements, leading to a cascade of recognition from additional great powers.Footnote 42 Similarly, Aydin and Regan demonstrate that when multiple external actors with similar preferences bandwagon in a civil war on behalf of one side, they are significantly more likely to reduce the duration of the conflict.Footnote 43 Rebel diplomacy via social media allows rebels to publicize support from third parties, thus bypassing the government’s media control and emphasizing to foreign audiences that international support for the rebels is widespread and growing.

Hypothesis 2: Rebel pronouncements regarding international support will increase future co-operation from external actors.

Secondly, foreign publics and elites are also concerned with the potential benefits of supporting the rebels. Public diplomacy allows rebels to shape foreign perceptions of the potential benefits of intervention by framing their own beliefs and preferences as commensurate with those of foreign audiences. This representation of the conflict increases the perceived benefits of co-operating with the rebels, because a rebel victory will be portrayed as producing a regime that is more closely aligned with outside actors’ preferences. It is critical for rebels to project interest similarity, because the extent to which a potential intervener’s preferences overlap with those of an insurgent group has been found to be a strong predictor of support to that group in both interstate and intrastate conflicts.Footnote 44

Hypothesis 3: Rebel pronouncements regarding their aims and beliefs will increase future co-operation from external actors with similar beliefs as the rebels.

Rebels can also persuade international audiences that their support will yield benefits by claiming that the government’s actions run counter to the prevailing international normative framework, and therefore merit international rebuke. Thus rebels will attempt to use social media to draw attention to government violations of international norms or the rule of law, or atrocities committed during the course of the conflict. Such a strategy is very important, as US public support for human rights is sensitive to sudden human rights violations and other major events.Footnote 45 Therefore, by providing vivid depictions of government human rights violations, rebels can mobilize foreign public support for intervention.

Hypothesis 4: Rebel pronouncements regarding government atrocities will increase future co-operation from international actors.

RESEARCH DESIGN

To test our theoretical insights, we adopt a within-subject design, tracing variation in the independent and dependent variables over time, rather than across cases. This method has three main advantages. First, it avoids making assumptions with respect to similarities across cases, as large-N studies often do.Footnote 46 Secondly, it provides a richer understanding of how the dependent and independent variables interact. Specifically, we compare days in which rebels use Twitter to convey messages with days they do not in order to evaluate how support for the rebels changes when rebels use public diplomacy via Twitter and when they do not. Thirdly, with respect to the dependent variable, we are able to measure US co-operation with the rebels at a more granular level by analyzing not simply whether the United States intervenes or not, but by tracing its specific behaviors (co-operative or conflictual) throughout the civil war.

While a within-case design affords several strengths, it nevertheless has potential drawbacks. Unlike in the case of experiments, the independent variable of interest (here, whether the rebels use Twitter or not) is not randomly assigned. If we could randomize the assignment of the independent variable, we could better isolate its effect, because the only systematic difference across observations would be whether they experience rebel diplomacy or not. Given the nature of this study, a randomized experiment is not feasible. As a result, there are two primary limitations associated with this research design.

First, although the within-case design eliminates some potential confounding factors that might arise across cases, it cannot remove all of them. Confounding factors are those that might correlate with both the dependent and independent variable and that, if not accounted for, might lead to a biased assessment of the magnitude of the relationship between the two. We meticulously control for the most plausible potential confounders to isolate the effect of social media on third-party behavior. Specifically, we include measures designed to account for the nature of the fighting on the ground and negotiations between the government and rebels (the reciprocal interactions of the Libyan Government and rebels), as well as the role of the US bureaucracy in determining US behavior.Footnote 47 Similarly, the robustness checks also account for traditional forms of diplomacy on the part of the rebels – such as press releases, meetings with foreign officials and public statements – to distinguish between the effect of the rebel messages disseminated via social media and the effect of the same messages disseminated via regular media.

Secondly, while our case represents a typical civil war (see the online appendix), the use of social media in the Libyan civil war might differ from other cases. These differences raise issues of external validity: can the results presented below be generalized to other cases? We address this and related questions in the last section of the article.

The Libyan Case

We investigate the impact of social media on the interaction between the Libyan Government, rebels and the United States during the Libyan civil war, which took place from February to October 2011. Peaceful demonstrations in mid-February quickly spiraled into violent clashes between the government and rebels. By the end of the month, the rebels created the National Transitional Council (NTC).

We focus on the international actor with the most prominent role in the crisis: the United States. Libyan rebels were particularly interested in securing US support for at least two reasons. First, the United States bore the brunt of the costs of the Libyan operation, even though it involved greater participation of non-US NATO members than previous NATO missions. Not only did the United States provide ‘70% of the coalition’s intelligence capabilities and a majority of its refueling assets’,Footnote 48 it also contributed 66 per cent of the total personnel involved, 52 per cent of the aircraft, 93 per cent of the cruise missiles fired and 34 per cent of sorties flown.Footnote 49 Despite providing vocal support for intervention, France and other NATO members lacked sufficient military capabilities to sustain the intervention without US support; for instance, non-US members ran low on precision-guided munitions less than one month into the conflict.Footnote 50 Secondly, the US has historically been the most frequent third-party intervener, accounting for roughly 24 per cent of all third-party military interventions in civil wars.Footnote 51

Thus securing US support was crucial for the rebels, but – importantly for our purposes – US support was by no means guaranteed. The United States was initially reluctant to be drawn into the conflict, so much so that the phrase ‘leading from behind’ was coined to define President Obama’s approach to Libya. There were sharp divisions on the feasibility of US involvement within the administration. The opposition was particularly powerful and vociferous, including Vice President Biden, National Security Adviser Thomas E. Donilon, Chief of Staff William M. Daley, Joint Chiefs Chairman Michael Mullen, Deputy National Security Adviser Denis McDonough, homeland security adviser John Brennan, and even Secretary of Defense Robert Gates. The latter was so adamant about this issue that he contemplated resigning in opposition.Footnote 52 There were few early supporters of a US intervention, among them UN Ambassador Susan Rice and White House adviser Samantha Power. President Obama and Secretary Clinton were undecided, wondering, in the words of Secretary Clinton, ‘who were these rebels we would be aiding, and were they prepared to lead Libya […]?’Footnote 53 Similar divisions were also echoed in Congress, where Senators Kerry, McCain, McConnell and Lieberman supported aiding the rebels and Democratic Representatives Lee, Woolsey, Honda, Grijalva and Waters loudly questioned the true motives of US involvement in Libya.Footnote 54

In this sense, the Libyan civil war presented the US leadership with a conundrum on how to respond.Footnote 55 This reluctance created a situation in which rebel diplomacy was pivotal in persuading the United States to take a more active role.

Twitter as a Tool of Rebel Diplomacy in Libya

Libya represents a useful case with which to examine the use of Twitter as a tool of rebel diplomacy. First, Libya in the year prior to the onset of conflict, in many respects, looks like a typical state that is at risk of experiencing civil conflict given its dependence on natural resource exports, a relatively high number of excluded ethnic groups, multiple neighbors experiencing civil conflict and a predominantly autocratic neighborhood.Footnote 56 Secondly, each of the actors in the conflict – the NTC, the Libyan Government and the United States – considered Twitter a key method of information dissemination about the conflict and, consequently, the NTC’s use of Twitter became a core component of a purposeful diplomatic strategy. This section proceeds by detailing why the Libyan civil war is a useful case for testing our hypotheses, and then offers some preliminary qualitative evidence to support our theoretical mechanisms before we turn to a more systematic evaluation of the rebel public diplomacy in the Libyan civil war.

Gaining Access to Foreign Audiences

From the initial days of the war, the NTC placed a great deal of importance on public diplomacy in order to win the support of international actors. In particular, the NTC focused on social media in order to weaken the traditional role of the media as an ‘information selector’.Footnote 57 This phenomenon of disintermediation was all the more important in Libya given the Gaddafi regime’s massive effort to maintain its privileged access to the media. As a CNN reporter remarked, Gaddafi actively sought to frame journalists’ perception of the war ‘through the windows of government buses driving along routes selected by government minders that show[ed] a pro-government landscape’.Footnote 58

To foster its public diplomacy effort, the NTC quickly established a Media and Communication Committee, which contained a dedicated Social Media Unit with the largest personnel allocation within that committee.Footnote 59 The official NTC Twitter account went live on 6 March 2011. To reach foreign audiences, the rebels tweeted almost exclusively in English and kept their Twitter account open. These choices expanded the reach of their message tremendously, as anyone, regardless of whether they were among the 18,000 official followers, or even possessed a Twitter account, could easily view all of their tweets.Footnote 60

Thus the NTC used Twitter as a diplomatic tool to build a large coalition by elevating a local crisis to the international level – an activity known as scale shifting.Footnote 61 The unique, many-to-many communication that social media offers is invaluable for social groups trying to build a large coalition.Footnote 62 Twitter was already a widely recognized means of disseminating information on dissident movements for international audiences by the start of the uprisings in Libya, at the tail end of the so-called Twitter revolution. By contrast, only 0.9 per cent of the Libyan population had access to Twitter in 2011, and barely 12 per cent of the population had internet access.Footnote 63 Despite this limited domestic access, the Libyan Government attempted to cut internet access in the country following the initial demonstrations, likely because they were wary of the opposition’s ability to use it to disseminate a compelling narrative abroad. To circumvent this action, the rebels devised a complex satellite system to maintain internet access.Footnote 64

Tailoring a Narrative of the Conflict

US elites were divided as to the merits of intervention. The type of information communicated by the NTC on Twitter was becoming increasingly important to ‘open source intelligence’ – public information that is readily available on the internet and that increasingly contributes to intelligence agencies’ assessment of developments on the ground. The CIA Open Source Center relies on such information to complement traditional intelligence sources because, in the words of its director, foreign actors sharing their perspective on social media helps them ‘by-pass foreign governments’ usual monopoly on the “official version” of the events’.Footnote 65 Moreover, important members of the Obama administration who had doubts about the intervention expressed the centrality of social media as a tool for gathering information on ongoing conflicts abroad. Secretary of State Clinton, for example, argued that ‘online organizing has been a critical tool for advancing democracy’, thus affirming the view of the Administration that ‘[…] the internet is a network that magnifies the power and potential of all others. […] Blogs, emails, social networks, and text messages have opened up new forums for exchanging ideas, and created new targets for censorship’.Footnote 66

Thus, once the NTC gained access to social media, it used public diplomacy to frame the conflict in order to garner foreign support. The leader of the NTC Social Media Unit understood that ‘leaders in the West were afraid of doing what they have done wrong before: arming and supporting groups that would go against them later on’.Footnote 67 In response to this perceived Western concern regarding the benefits of supporting the rebels, the NTC Media Unit employed Twitter to project an image that could resonate with the American public and leaders. For example, the rebels exploited US public opposition to civilian targeting by tweeting copiously about Gaddafi’s attacks on civilians, because they knew that, in the words of the head of the Social Media Unit, ‘[Gaddafi’s] atrocities gave [them] a better cause’.Footnote 68 Indeed, when asked whether the United States should intervene to prevent a massacre in Libya, 56 per cent of the respondents gave a positive answer, and 83 per cent of the population declared the protection of civilians in Libya against Gaddafi’s attacks a very important or somewhat important US foreign policy goal. Support was less widespread when Americans were simply asked if the United States should intervene to suppress Gaddafi.Footnote 69

For supporters of US assistance to the rebels, the public nature of the NTC’s statements on Twitter also played an important role, because it partially reduced the typical information asymmetry between the public and the administration on matters of national security. As part of their strategy, rebels kept their account open to spread their message more broadly. The press also used the Twitter feed as a source of information on the conflict; the NTC counted among its official followers many media outlets such as the magazine Foreign Policy, RT and the BBC. Rebel pronouncements via Twitter created an environment in which supporters of intervention could credibly signal that intervention is in the broader national interest. In fact, supporters of intervention emphasized the publicity of the rebels’ statements. In Senate hearings, the deputy secretary of state affirmed that the secretary of state had agreed to meet the NTC because the group had ‘publicly stated its commitment to democratic ideals and its rejection of terrorism and extremist organizations, including Al-Qaeda’.Footnote 70 For him, the rebels’ public statements were crucial in determining their aims, arguing that ‘though it will be important to ensure that words are matched by actions, [the Administration has] been encouraged by the NTC’s public statements on democracy, treatment of prisoners, human rights and terrorism’.Footnote 71 Moreover, Twitter allowed rebels to offer a detailed, informed and readily available framing for US advocates of intervention – that is, talking points,Footnote 72 which were important for rallying US support. Civil wars are often characterized by scarce information, and therefore may become a breeding ground for conflict within elite circles.Footnote 73 For example, the rebels’ conscious rejection of terrorism and description of themselves as ‘freedom fighters’ successfully reverberated in American presentations of who the rebels were. Under Secretary for Political Affairs Burns claimed that America had ‘to support the courageous Libyans who have risen up to regain their rights’.Footnote 74

Data

To measure the conflict dynamics on the ground between the Gaddafi regime, the NTC and the United States, we collected original event data from LexisNexis newswire reports, which we processed using the software TABARI. Using newswires allows us to paint a fine-grained picture of dynamics within the conflict while reducing the reporting bias introduced by media fatigue and other forms of incentive-based media distortions that are more likely to affect articles from news outlets such as the New York Times.Footnote 75 Moreover, this allows us to capture the conflict dynamics between the government, the NTC and the United States independent of the rebels’ use of Twitter.

To ensure the integrity of the data, we omit any newswire report that relies exclusively or primarily on Twitter as a source of information. We also eliminate duplicate reports, to avoid having multiple records of the same event. Events in newswires are coded using the CAMEO event ontology, which includes twenty categories of events ranging from severe conflict to intense co-operation in all realms of foreign and domestic policy – diplomatic, military and economic (see the online appendix). With these event data, we build time series that describe the daily actions of: the government toward the rebels; the rebels toward the government; the United States toward the rebels; and the United States toward the government. For example, the time series capturing US behavior toward the rebels measures the US foreign policy actions that emerge from both the domestic decision-making process – including secret intelligence, public opinion polls, congressional hearings, executive orders and the like – and responses to events on the ground in the civil war. These series allow us to reconstruct and understand the interactions between the three actors as interconnected sequences of actions and reactions, rather than as isolated episodes of conflict. With these series, we are able to measure and control for the effect of developments on the ground when evaluating the independent effect of the rebels’ use of social media.

Event data are quite comprehensive: they record information on material and verbal conflict, as well as material and verbal co-operation. As a result, when recording Gaddafi’s behavior toward the rebels, for example, event data capture events as diverse as Gaddafi’s brutal suppression of rebel forces (25 February) and his offers of a ceasefire agreement (26 July). In order to categorize the different intensities of conflict or co-operation that material and verbal acts entail, we use the Goldstein scale, which is broadly employed in the literature (examples and descriptive statistics in the online appendix). The scale allows us to use these comprehensive data without sacrificing precision by parsing out pairs of events that are, for instance, both conflictual, but that entail different intensities of violence. For example, the US condemnation of Gaddafi’s protest repression on 26 February, and the US decision to use drone strikes against Gaddafi’s forces on 23 April both represent hostile behavior on the part of the United States toward Gaddafi, but the drone strikes involve a greater intensity of conflict than the verbal condemnation.

Given their comprehensiveness and precision, event data offer a measure of third-party involvement that is much more granular than the dichotomous measure used in many studies of intervention in civil war.Footnote 76 In other words, rather than measuring foreign intervention as a dichotomous event – did the United States intervene or not – based on an arbitrary threshold, we are able to track the full spectrum of US behavior in the conflict, including acts of co-operation and conflict (both verbal and material) throughout the civil war.

Twitter Data

To measure the impact of rebel diplomacy through Twitter, we collect original data on the Twitter activities of the primary rebel organization in the Libyan civil war, the NTC, which was active on Twitter from 6 March 2011 (we provide examples and discussion in the online appendix). Our focus is limited to examining the effect of social media as a tool of rebel diplomacy rather than studying the effect of the whole social media sphere. Therefore we restrict our measurement to the NTC Twitter account to avoid measurement error. The provenance and objectives of other non-governmental Twitter accounts, as well as YouTube channels, that provided information on Libya during the conflict are very heterogeneous. Some of them were the brainchild of second-generation Libyan emigrants to Europe. Since no direct, official link between these accounts and the NTC has been established, we cannot use them to measure the impact of the rebel organization’s use of Twitter as a tool of diplomacy without introducing inaccuracies and noise in the data.

We code all of the messages that were tweeted by the NTC official account during that period into four categories, based on their content (publicizing international support, remarking battlefield success, denouncing government atrocities and clarifying the rebels’ aims).Footnote 77 Appendix Table 1 provides examples of the tweets we code. Next, we generate a daily count of each category of tweets reflecting the number of tweets of each type the NTC transmitted on a given day. This procedure results in five total Twitter series: one for each of the four categories of tweets, and a fifth that is a count of the total number of tweets sent by the NTC each day, irrespective of their type. Because these Twitter variables are daily counts, we standardize each of the series when including them in the vector autoregressive (VAR) models. In the models, we do not impose any assumptions regarding when these tweets should impact US behavior – that is, should their impact be immediate, or lagged? Instead, we test different model specifications and triangulate using different tests to determine which one best represents the dynamics in the data (see discussion below).

The Model

To model the effect of Twitter on the dynamic interactions between the Libyan Government, the rebels and the United States, we build on a large tradition of studies of conflict interactions by estimating a VAR.Footnote 78 Formally, the VAR builds on structural equation models, and considers interactions between a set of actors K as dependent on the present and past values of each of the actors and their counterpart, for a p number of lags. For example, in a system with two actors (K=2), the standard-form VAR is:Footnote 79

In both equations, y 1(t) and y 2(t) are stationary, while ϵ 1(t) and ϵ 2(t) are white noise residuals. Generalizing to multiple equations, and multiple lags, the VAR is estimated as:

Y t is a kX1 vector of endogenous variables, A 0 is a kX1 vector of intercepts, A i is a kXk vector of coefficients and E t is a kX1 vector of error terms, while p is the number of lags. Here, each of the K endogenous time series represents one of the following: the rebels’ actions toward the Libyan Government, the Libyan Government’s actions toward the rebels, the US Government’s actions toward the rebels, the US Government’s actions toward the Libyan Government and each of the five types of tweets identified in the previous section.

This modeling technique presents at least four advantages for the study of the Libyan civil war, and of conflict dynamics more broadly. First, since each time series in vector Y t impacts the others in vector Y t , the model makes it possible to model conflict events as the outcome of the action and reaction dynamics between multiple actors. For example, the VAR captures the fact that the US decision to use drone strikes on Gaddafi’s forces on 23 April was the product of not only US intelligence and domestic decision-making processes, but also the Libyan Government’s behavior toward the rebels, and the rebels’ behavior toward the Libyan Government, on 23 April and during their past interactions.

Secondly, since Y t in Equation 2 is specified as a vector of endogenous variables, the VAR explicitly incorporates and models the endogenous relationship between these interactions, as we elaborate below. For example, the United States might express doubts about intervention, emphasizing how little is known about the rebels. To address this concern, the rebels may use Twitter to publicize their rejection of terrorism and support for democracy. In order for us to correctly assess the impact of such tweets on subsequent US behavior, it is necessary to explicitly incorporate the fact that the rebels’ tweet originated, in part, in response to previous US behavior toward the rebels. The VAR model addresses precisely this type of endogenous relationship between all these series, which allows us to model the conflict process as a whole, and to test whether rebel Twitter usage has an independent effect on any of the other series in the model.

Thirdly, since the number of relevant lags, p, is derived from the data, the degree to which decisions such as the one in our example depend on past interactions between the rebels, the government and the United State is endogenously determined from the data, rather than arbitrarily assumed (see the online appendix).

Finally, the VAR model makes it possible to compare US behavior toward the rebels under two conditions: when rebels use Twitter as a tool of diplomacy and when they do not, thus providing a counterfactual condition to analyze how US behavior varies in the presence and absence of rebel diplomacy through Twitter. This is the case because each of the endogenous variables in vector Y t is a time series that tracks the behavior of the actors of interest over time, rather than just recording the moments when they engage in a specified action.

In sum, the use of a within-case research design in conjunction with the VAR model allows us to ask: given the complex interactions between the United States, the rebels and the Libyan Government that characterized the Libyan civil conflict, and the endogeneity between them, did NTC diplomacy via Twitter significantly change US behavior in the civil war? That is, following days in which the rebels use social media, does US behavior become more co-operative than it does following days in which the rebels do not use social media?

RESULTS

A VAR with k equations and p lags contains k×((k×p)+1) coefficients, which means that no single coefficient or subgroup of coefficients can represent the substantive and statistical significance of the impact of changes in one variable.Footnote 80 Instead, the outcomes of the model have to be illustrated via graphs that track changes in the whole system of equations by taking into account how changes in one variable ripple through the whole system.Footnote 81

The Impact of Twitter on US Behavior

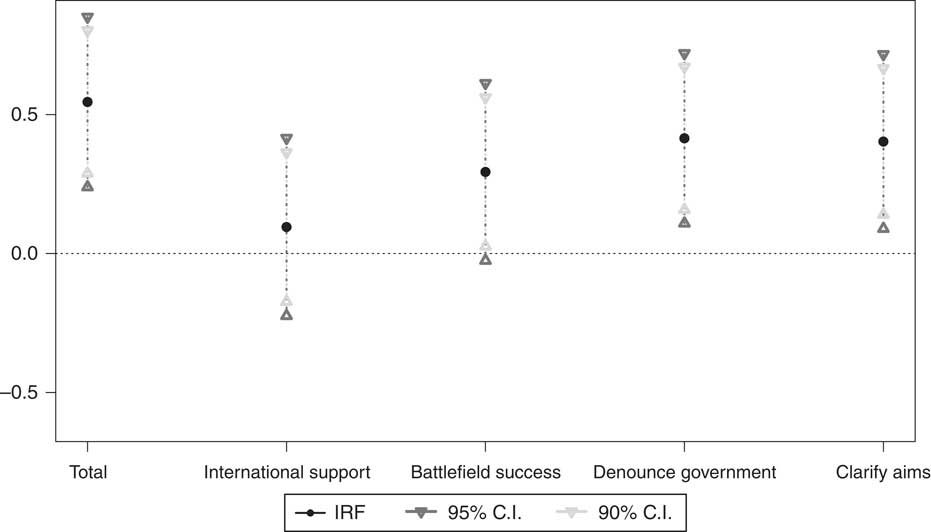

To assess whether Twitter represented an effective tool of rebel diplomacy, we investigate its impact on US actions toward the Libyan rebels via item response function graphs (IRFs) in Figure 1. The black dots within each plot answer the question: if the rebels tweet a specific message, does US behavior toward the rebels become more co-operative (positive values), more conflictual (negative values) or remain unchanged over time? In Figure 1, the x-axis represents each of the five types of Twitter series: one series that conflates all the tweets together, irrespective of the message; one that only codes tweets on international support; one that only codes tweets on battlefield success; one that only codes tweets that clarify aims; and one that only codes tweets that publicize atrocities. The y-axis represents the degree to which the United States becomes co-operative (for values above 0) or conflictual (for values below 0) toward the rebels in response to that tweet, while controlling for the interactions between the United States and the government, and between the government and the rebels. In technical terms, the black dots trace how a one-standard-deviation positive shock in a specific variable (Twitter, the impulse function) affects another variable (US behavior toward the rebels, the response function), accounting for dependencies across the whole system of equations over time.

Fig. 1 Twitter effect on US behavior toward the rebels Note: IRF graphs for VAR models show the impact of a one-standard-deviation increase in the number of each type of tweet on the US behavior toward the rebels four days after the increase in Twitter usage occurs. For more IRF results, see the online appendix.

Starting from the left-hand side of Figure 1, we find that tweets have a positive, significant effect on US behavior toward the rebels, controlling for the activities on the ground between rebels and the government, for US actions toward both the government and the rebels, and for the endogeneity that characterizes activities between these actors and Twitter. Disaggregating these tweets to examine which messages impact US behavior, we find that messages that speak to the benefits of intervening on the side of the rebels increase US co-operation toward the rebels, thus making Twitter an effective tool of rebel diplomacy. Specifically, compared to days in which Libyan rebels do not use Twitter as a tool of diplomacy, US behavior toward the rebels becomes significantly more co-operative when the rebels use Twitter to express preferences similar to those of the United States on respect for human rights, democracy and opposing terrorism, and to convey information regarding human rights abuses and the illegitimacy of the Libyan Government. This finding supports Hypotheses 3 and 4.

Rebel attempts to persuade foreign audiences of their shared beliefs and values, for example by repudiating terrorism, correspond to a 2.5 per cent increase in the level of US co-operation with the rebels.Footnote 82 By comparison, a co-operative gesture toward the government on the part of the rebels outside of social media, for example expressing support for a ceasefire through traditional media, only increases US co-operation with them by 0.9 per cent, which is indistinguishable from zero at the 90 per cent confidence level, indicating that diplomacy via Twitter can produce a larger shift in US co-operation than does rebel behavior toward the government.

On average, the effect of Twitter as a tool of rebel diplomacy is not immediate; the impact is evident after four or five days. Moreover, as Figure 2 shows (see discussion below), the substantive impact of Twitter grows over time. Taken together, these two findings – that it takes tweets a few days to start affecting US behavior toward the rebels, and that their effect grows over time – provide further evidence that diplomacy via Twitter impacts US behavior toward the rebels by shaping the perception of the conflict in the United States, rather than a more immediate mechanism, such as the provision of battlefield information. At the same time, the relatively prompt time frame within which Twitter affected US behavior reflects the famously accelerated time frame that characterized the decision making regarding the Libyan civil war in the United States – the speed spurred a momentous debate on the proper timing of force authorization and the legacy of the 1973 War Powers Act more broadly.Footnote 83

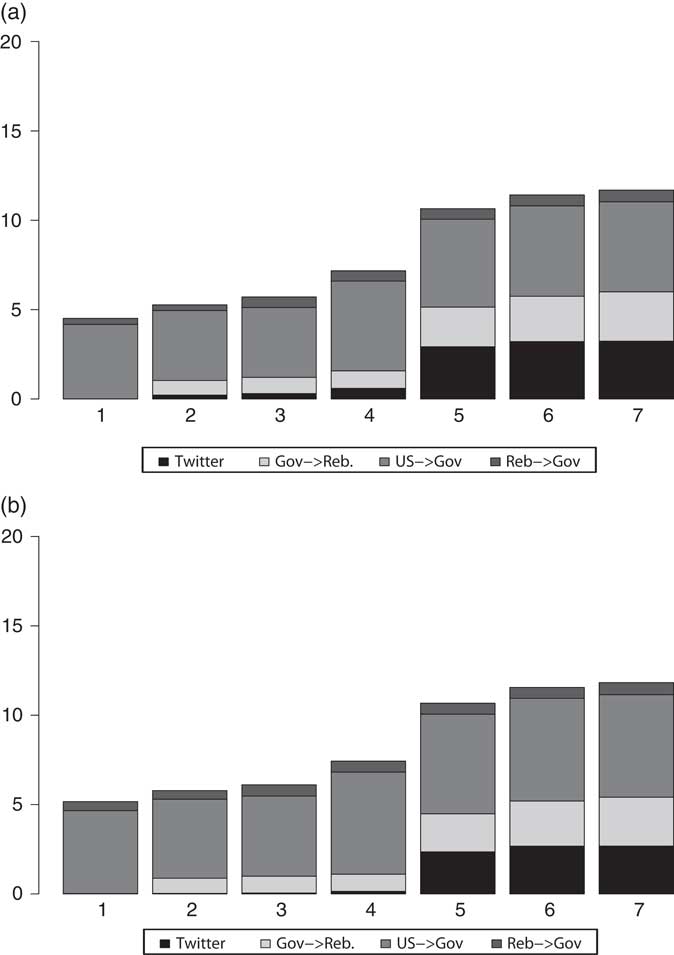

Fig. 2 Forecast Error Variance Decomposition (FEVD) graphs, VAR(4) model. (a) Clarify aims and beliefs; (b) Publicize government atrocities Note: the plot presents the percentage of US behavior toward the rebels (response function) that is explained by other series in the model, over seven days.

Taken together, these results confirm the importance of rebel diplomacy in understanding developments within civil wars, while suggesting a nuanced understanding of its effectiveness. Specifically, rebel diplomacy is less effective when it conveys information that is readily accessible through other channels, such as information about international support or battlefield outcomes. It is more effective when it allows actors who are relatively unknown in the international arena to project a positive image to international audiences as a credible and preferable alternative to the local government, while overcoming that government’s privileged access to international media.

Substantive Significance

The Forecast Error Variance Decomposition (FEVD) graphs presented in Figure 2 examine the substantive significance of the results by gauging the relative importance of rebel diplomacy via Twitter compared to other determinants of US behavior toward the rebels. It displays what percentage of US behavior toward the rebels is explained by the behavior of other actors, rather than by US intelligence and decision-making processes.Footnote 84 For example, when the United States used drone strikes against the Libyan Government on 23 April, the FEVD plots determine what percentage of that action was explained by the actions of the government toward the rebels (light gray areas), of the rebels toward the government (dark gray areas), of the United States toward the Libyan Government (medium gray areas) and rebel diplomacy via Twitter (black areas).

We find that bureaucratic politics within the United States has a large substantive effect on determining US behavior in the conflict. This suggests that, intuitively, US policy toward the rebels is influenced by past US policy toward the rebels, as these past policy actions reflect the culmination of US intelligence, military and political decision-making processes, which in turn continue to shape US policy moving forward. However, as Figure 2 indicates, US domestic politics is not the sole determinant of US behavior toward the rebels, and as time passes, the behavior of other actors in the conflict plays a growing role in shaping future US behavior.

Most notably for our purposes, the rebel use of social media displays a moderate, but clear, substantive impact on US behavior toward the rebels. With a four- or five-day lag, rebel diplomacy (black area) becomes as important a determinant of US behavior toward the rebels as the Libyan Government’s actions toward the rebels (light gray area). This suggests that US behavior toward the rebels is determined in large part by its own domestic decision-making process, but that outside forces help shape US actions in the conflict, and rebel use of Twitter plays a meaningful role in that process.

In sum, we find that Twitter was an effective tool of rebel diplomacy: when rebels used it to emphasize the similarity of their own beliefs and values with those of foreign audiences, and the divergence of the existing government’s beliefs and behavior from those values, US co-operation toward the rebels increased over the following week, controlling for the US intelligence and domestic decision-making processes, as well as the interactions between the Libyan Government and rebels, and the endogeneity between all these factors. Conversely, in the counterfactual situation when rebels did not engage in diplomacy via Twitter to spread these messages, US co-operation with them was lower. These results hold even when controlling for more traditional forms of rebel diplomacy, as well as for the interaction of the United States and NATO.

Robustness Checks: Traditional Diplomacy and NATO

We estimate a model in which we control for more traditional forms of diplomacy on the part of rebels to account for whether the effect of public diplomacy via Twitter on third parties’ policies toward the rebels is significant, even when controlling for other mediums of rebel diplomacy. This series includes both material and verbal acts on the part of the rebels toward the United States. Such acts are often geared toward spreading their narrative of the conflict abroad: for example, sending delegations abroad, meeting with Secretary of State Clinton or releasing press statements to traditional media organizations. This series accounts for numerous additional pathways through which rebels attempt to interact with foreign audiences, both directly and indirectly, by relaying messages through the media. Our results are robust (see Appendix Figure 4), which is consistent with our claim that Twitter enables a unique form of diplomacy that is distinct from more traditional diplomatic acts. We then estimate a model in which we also control for the interactions between the United States and its NATO allies. Examples of these interactions are the emergency meeting called by the NATO secretary general to discuss the Libyan situation (25 February) and the US appeal to its NATO allies to step up their contribution to the mission (10 June). Our results on the impact of Twitter are robust (see Appendix Figure 5), which is consistent with the fact that both the material and strategic impact of NATO on the Libyan operation was, in the words of Secretary of Defense Gates, ‘dismal’ (see the Appendix for discussion).

TOWARD A RESEARCH AGENDA ON PUBLIC DIPLOMACY IN CIVIL WARS

The Libyan case shares many common characteristics of states that experience civil war (see Appendix), making it a useful case for evaluating the impact of rebel use of public diplomacy. However, an in-depth analysis of a single case is insufficient to offer definitive inferences regarding the generalizability of the findings, due to potentially important differences across cases regarding the use of public diplomacy. During the Syrian civil war, for instance, multiple rebel groups have used social media, often to reach foreign audiences.

This variation in the use of social media raises an issue with respect to the generalizability of our results: to what extent does the evidence we presented for the Libyan civil war apply to other cases? In this section, we present a research agenda, delineating important questions left to explore to understand the role of social media in public diplomacy, and clarifying what our exploratory test (Libya) suggests about them.

The first set of questions concerns the actors that utilize social media. For example, how will opposing messages from multiple rebel organizations in the same conflict affect the narrative that foreign audiences observe? In Syria, for instance, multiple rebel actors with divergent preferences use social media to propagate their narrative of the conflict. Bob suggests that different rebel groups often compete to gain the support of transnational organizations.Footnote 85 Our results suggest that the NTC increased US co-operation by using social media to consistently frame itself as preferable to the current regime. However, in Libya there was a single rebel organization. Further research may usefully evaluate whether such a narrative might prove similarly impactful if it is only one message among many from rebel groups in the conflict.

Situations with multiple competing messages lead to another avenue for research: how can a third party ascertain the ‘type’ of a particular rebel group (for example, whether their preferences are consistent)? In the case of Libya, we draw on observational and experimental studies that demonstrate that cheap talk can shape the beliefs and perceptions of actorsFootnote 86 to argue that rebel public diplomacy was useful in framing the conflict to mobilize potential supporters abroad. Further research may extend this analysis by exploring the strategic interplay between third parties and rebel groups in the context of a signaling game with incomplete information.

Similarly, it will be fruitful to further investigate the conditions under which the government will use Twitter. In Libya, we find that rebels used public diplomacy to fight the government’s privileged access to the media, while the government responded by trying to cut internet access. By contrast, the Syrian Government has also taken to Twitter extensively in an effort, much like rebel organizations, to frame the nature of the conflict and portray itself as opposing extremism. Similarly, the Israeli Defense Forces have been actively engaging Hamas on social media for years in an effort to condemn Hamas’ behavior, report atrocities carried out by Hamas and defend their own actions.Footnote 87 New research on these issues can usefully contribute to the current debate on whether new communication technologies expand or curtail the state’s repressive power.Footnote 88

A second set of research questions deals with the nature of the diplomatic effort itself. For example, how does rebels’ use of social media correspond to their organizational capacity? Evidence from the Libyan case suggests that the relationship between the strength of the NTC organization and the shape of the diplomatic effort is by no means trivially evident. On the one hand, it is possible to surmise that the more resources the rebels possess, the greater the opportunity they have to use this tool to convey a consistent image. As the Libyan case demonstrates, the diplomatic effort requires many and different resources to sustain their image-framing attempt – from devising a complex satellite system to circumvent the government’s internet shutdown to allocating a dedicated set of personnel to the Social Media Unit. On the other hand, the NTC case also suggests that the weaker the rebel group is, the greater its willingness to use public diplomacy to reach out to potential interveners. The rebels felt an urgent need to attract foreign support, especially when they were weak. Further research on the relationship between rebel capacity and their reliance on social media and diplomacy can increase our understanding of the role played by rebels in the course of civil wars as strategic actors, not just in the context of their interactions with the local government, as present studies investigate,Footnote 89 but also in the international arena.

A related question is how the use of social media as a tool of rebel diplomacy will evolve over time. The centrality of Twitter as a tool for scale shifting emerged forcefully after the so-called Arab Spring, which made it an important ‘focal point’ for public diplomacy. Indeed, the ability of a particular tool to facilitate access to the target audience is an important permissive condition of public diplomacy’s effectiveness: using Twitter would be of little or no help to rebels if it were not used by their audience, just as publishing a pamphlet would have been useless to Thomas Paine if none of his target audience was literate. However, findings in the Libyan case suggest that the fact that Twitter usage was widespread was not per se sufficient to guarantee the success of the diplomatic effort. Our finding that not all types of transmitted messages were effective suggests that the content of the messages was also key in determining the usefulness of the tool. Further research on the impact of different tools of public diplomacy can enrich our understanding of this crucial activity in the international arena.Footnote 90

CONCLUSIONS

The implications of our results extend to several fields of study, highlighting fruitful opportunities to connect different areas of research. First, by modeling the relationships between the government, the rebels and the United States throughout the crisis in a granular fashion, taking into account individual episodes of co-operation or conflict, this analysis reveals the active role of rebels as strategic players attempting to win further support from external powers as the conflict unfolds.Footnote 91 This insight, in turn, emphasizes the importance of bringing recent findings on the political effects of social mediaFootnote 92 to bear on the investigation of third parties’ decisions about whether to intervene.Footnote 93 Secondly, these results suggest that rebels often decide to shift resources away from the battlefield and toward diplomacy, which highlights the importance for the literature on rebel diplomacy of studying how rebels calculate this trade-off in resource allocation.Footnote 94 Finally, by showing that Twitter is an effective vehicle of public diplomacy, these results underscore the importance of extending the research on the effectiveness of diplomacyFootnote 95 to interactions within the civil war context.