Introduction

Nets are important gear for fishing that provide many people with both food and income; however, they have a variety of direct and indirect negative impacts on aquatic biodiversity (Piatt & Nettleship Reference Piatt and Nettleship1987, Ayaz et al. Reference Ayaz, Acarli, Altinagac, Ozekinci, Kara and Ozen2006, Read et al. Reference Read, Drinker and Northridge2006, Blettler & Wantzen Reference Blettler and Wantzen2019, Gough et al. Reference Gough, Dewar, Godley, Zafindranosy and Broderick2020, Kelkar & Dey Reference Kelkar and Dey2020, Vitorino et al. Reference Vitorino, Ferrazi, Correia-Silva, Tinti, Belizário and Amaral2022). In Brazil, the sale nets is unregulated, with any buyer permitted to purchase any type of net, either from physical stores (Fig. 1a) or through online suppliers (Azevedo-Santos et al. Reference Azevedo-Santos, Hughes and Pelicice2022). Only authorized fishermen and fisherwomen are legally permitted to use fishing nets, but sales of these nets without control and the difficulty of enforcing restrictions on their use contribute to widespread illegal fishing in Brazil (Supplementary Appendix S1, available online).

Fig. 1. Events involving fishing nets in Brazil: (a) example of the free sale of fishing nets in a physical store; (b) example of fish (orders Characiformes, Cichliformes and Siluriformes) caught in a gill net; (c) a freshwater turtle captured in a gill net; and (d) a ghost net found with remains of fish in it.

Despite studies demonstrating the impacts of fishing nets on Brazilian biodiversity (e.g., Possatto et al. Reference Possatto, Barletta, Costa, do Sul and Dantas2011, Santos et al. Reference Santos, Bellini, Bortolon and Coluchi2012, Iriarte & Marmontel Reference Iriarte and Marmontel2013, Adelir-Alves et al. Reference Adelir-Alves, Rocha, Souza, Pinheiro and Freire2016, Azevedo-Santos et al. Reference Azevedo-Santos, Marques, Teixeira, Giarrizzo, Barreto and Rodrigues-Filho2021, Gallardo et al. Reference Gallardo, Fossile, Herbst, Begossi, Silva and Colonese2021), no empirical data on the free sale of nets are available, and there have been no specific recommendations for regulating their sale. We examined advertisements for fishing nets and surveyed the mesh sizes and chemical compositions of the nets offered for sale by two major online markets in Brazil: AliExpress and Mercado Livre. Here, we discuss the ways in which this unregulated commerce facilitates illegal fishing and impacts biodiversity, and we provide suggestions for regulating the sale of fishing nets in Brazil.

Sale of fishing nets

We searched the AliExpress (https://best.aliexpress.com/) and Mercado Livre (https://www.mercadolivre.com.br/) websites for the hypothetical purchase of fishing nets (see ‘Methods’ in Appendix S2). We found a total of 72 advertisements for fishing nets (none requiring specific authorization to purchase); the nets comprised ‘cast nets’ (29.2%), ‘gill nets’ (52.8%), ‘trawl nets’ (8.3%) and ‘nets for fishing rods’ (9.7%). The mesh sizes ranged from 2 to 24 cm (between opposite knots). Most nets found for sale were composed of nylon (59.7%) or unspecified plastic (1.4%). In 38.9% of the advertisements, the material from which the nets were made was either not provided or we were unable to find such information.

Consequences of the free sale of nets

Our searches demonstrated that people from any region of the country could acquire fishing nets (including those with small mesh sizes) on both websites assessed. In both physical (Fig. 1a) and virtual commerce, the sellers are not required to ask for an attestation or authorization certificate when fishing nets are purchased (Azevedo-Santos et al. Reference Azevedo-Santos, Hughes and Pelicice2022). In the specific case of AliExpress, this problem is exacerbated by the fact that the fishing nets are imported into the country and cross the border without any environmental restrictions in place.

In Brazil, federal law restricts the use of fishing nets to professional fishers and to researchers; prior authorization is required in both cases (Brazil 2009). Restrictions on their use include limits such as refraining from fishing during the spawning period. In general, professional fishers are required to be registered at a government-approved cooperative or similar entity. However, unregulated fishing is common in Brazil (Chagas et al. Reference Chagas, Costa, Martins, Resende and Kalapothakis2015), and nets are the principal type of equipment used in such fishing. As these nets can be purchased without legal restrictions, inspections are conducted throughout the country only when the nets are being used in water bodies. Monitoring is hampered by the logistics of patrolling vast areas that are often inaccessible, especially in Amazonia. Recent examples (Appendix S3) of the difficulty of inspecting illegal mining in or near Amazonian rivers illustrate this. The free access to fishing nets facilitates the illegal fishing that is already occurring (e.g., Azevedo-Santos et al. Reference Azevedo-Santos, Hughes and Pelicice2022; see also Appendix S1) – especially in Amazonia and in other parts of the country where conducting inspections is difficult.

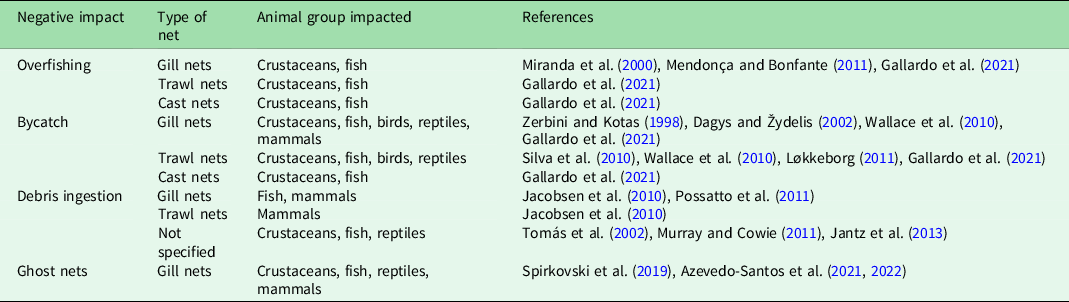

Fishing nets are an efficient type of fishing gear for catching fish (e.g., Fig. 1b; Ramos et al. Reference Ramos, Lustosa-Costa, Lima, Barbosa and Menezes2021), but their use may also result in the accidental capture of other animals (Fig. 1c; Reeves et al. Reference Reeves, McClellan and Werner2013). Gill nets constitute a much larger problem in terms of overfishing and bycatch due to the large areas they can cover and the long period during which they often remain in the ecosystem when compared to other net types (e.g., cast nets). Various studies have documented the accidental capture of animals in gill nets (e.g., Table 1). The free access to these nets and their consequent illegal use contribute to overfishing and bycatch, both of which impact biodiversity negatively.

Table 1. Examples of negative impacts on aquatic animals caused by different types of fishing nets.

Pollution is also facilitated by unregulated sales of nets. Most nets are made of nylon (as shown by our survey), a material that is difficult to degrade (Link et al. Reference Link, Segal and Casarini2019). After being abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded, the nets become sources of pollution in the ecosystems concerned (Azevedo-Santos et al. Reference Azevedo-Santos, Hughes and Pelicice2022). Ingestion of polyamide is a concern regarding both marine and freshwater fish (e.g., Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Wang, Chen, Sun, Qu and Xia2019, Maaghloud et al. Reference Maaghloud, Houssa, Bellali, El Bouqdaoui, Ouansafi, Loulad and Fahde2021), including those in Brazil (Pegado et al. Reference Pegado, Schmid, Winemiller, Chelazzi, Cincinelli, Dei and Giarrizzo2018, Andrade et al. Reference Andrade, Winemiller, Barbosa, Fortunati, Chelazzi, Cincinelli and Giarrizzo2019, Neto et al. Reference Neto, Rodrigues, Ortega, Rodrigues, Lacerda and Coletto2020). Fishing nets may represent a major source of the polyamide and other harmful compounds ingested by fish and other aquatic animals, including reptiles and large mammals (Table 1).

Free sale and illegal use also increase the number of nets left in the ecosystem, whether intentionally or not (Azevedo-Santos et al. Reference Azevedo-Santos, Hughes and Pelicice2022), resulting in ‘ghost nets’ (Barbosa-Filho et al. Reference Barbosa-Filho, Seminara, Tavares, Siciliano, Hauser-Davis and Mourão2020, Vitorino et al. Reference Vitorino, Ferrazi, Correia-Silva, Tinti, Belizário and Amaral2022; see also Fig. 1d), which impact aquatic fauna ranging from invertebrates to fish to large mammals (Table 1), including in Brazil (Barbosa-Filho et al. Reference Barbosa-Filho, Seminara, Tavares, Siciliano, Hauser-Davis and Mourão2020, Azevedo-Santos et al. Reference Azevedo-Santos, Marques, Teixeira, Giarrizzo, Barreto and Rodrigues-Filho2021, Reference Azevedo-Santos, Hughes and Pelicice2022).

The need for a law to regulate net sales

Although Brazil still has no federal regulation of fishing net sales, in 2015 a bill (PL 206/2015) was presented to the federal legislature’s Chamber of Deputies that would prohibit ‘the manufacture, sale and use, throughout the National Territory, of fishing nets, with mesh smaller than 5 cm …’ (Brazil 2015). However, the bill was considered ‘too drastic’, and in 2019 it was shelved in the Chamber of Deputies.

A new bill is needed that could be approved and implemented without creating conflicts with authorized fishers and other groups. A clear example demonstrating that this is possible is Tocantins State Law 3249 of 24 July 2017, restricting the sale of nets to licensed fishers in that state (Diário Oficial de Tocantins Reference Oficial de Tocantins2017). Although this represents an advance in the state of Tocantins, its effect is undermined by the ease of purchasing nets in other states and via online sales. A law is needed at the federal level patterned on the law in Tocantins; however, we emphasize that the control of nets at the point of sale cannot replace inspection and monitoring of their use.

Drafting a federal bill requires the participation of the fisheries sector in addition to researchers (Azevedo-Santos et al. Reference Azevedo-Santos, Fearnside, Oliveira, Padial, Pelicice and Lima2017). This collaboration is needed to balance provisioning and regulating ecosystem services and to avoid interpretations that could harm professional fishers and other sectors authorized to use fishing nets.

Conclusions

Sales of fishing nets in Brazil require no form of environmental authorization, yet the unregulated sale of these nets facilitates illegal fishing – which could contribute to overfishing, bycatch, pollution and ghost netting. The current scenario requires federal legislation (similar to an existing law in Tocantins State) regulating the sale of fishing nets throughout Brazil. However, this does not replace the need for ongoing inspection of fishing activities (legal or illegal) in the country’s waterbodies.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892922000273.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the editor, Nicholas Polunin, for comments and corrections. This manuscript was improved with the comments of three anonymous reviewers, to whom we are extremely grateful.

Financial support

TG and PMF were supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq; Proc. # 311078/2019-2 to TG; 311103/2015-4 and 312450/2021-4 to PMF).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

None.