Introduction

Dementia commonly occurs in the context of pre-existing family relationships that continue to develop over time, evolving dynamically as developmental transitions and challenges occur over the lifecycle (Ablitt et al., Reference Ablitt, Jones and Muers2009; Quinn et al., Reference Quinn, Clare and Woods2009). In turn these family relationships impact upon the way in which dementia is experienced and the associated outcomes for all family members (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Macmillan and Brown2012; Pozzebon et al., Reference Pozzebon, Douglas and Ames2016; Hutchinson et al., Reference Hutchinson, Roberts, Roach and Kurrle2020). For example, evidence attests to the reciprocal influence of prior and current relationship quality and wellbeing of spouses when one has a diagnosis of dementia (Fauth et al., Reference Fauth, Hess, Piercy, Norton, Corcoran, Rabins, Lyketsos and Tschanz2012; Colquhoun et al., Reference Colquhoun, Moses and Offord2019). Additionally, the experiences and wellbeing of spouses and adult children can be positively or negatively influenced by the supportiveness of other family members and the extent to which such support is sought and welcomed (Shim et al., Reference Shim, Barroso and Davis2012; Pozzebon et al., Reference Pozzebon, Douglas and Ames2016; Tatangelo et al., Reference Tatangelo, McCabe, Macleod and Konis2018).

However, research has often excluded the perspectives of people with dementia despite evidence that they value their family relationships and actively contribute to them (Ablitt et al., Reference Ablitt, Jones and Muers2010; Hedman et al., Reference Hedman, Hansebo, Ternestedt, Hellström and Norberg2013; Wolverson et al., Reference Wolverson, Clarke and Moniz-Cook2016). Where the person with dementia is aware of the impact of their condition upon their partner, this has been found to enhance relationship quality (Clare et al., Reference Clare, Nelis, Whitaker, Martyr, Markova, Roth, Woods and Morris2012; Spector et al., Reference Spector, Orrell, Charlesworth and Marston2016).

Family relationships and dementia

Research is increasingly exploring the relational context of dementia. Dementia brings particular psychosocial challenges, including changes to roles and relationships which require adjustment and adaptation over time (Rolland, Reference Rolland1994; Bielsten and Hellström, Reference Bielsten and Hellström2019). Studies suggest that family members are required to take increasing responsibility as the person with dementia becomes less able to undertake the relational work associated with togetherness (La Fontaine and Oyebode, Reference La Fontaine and Oyebode2014). These findings reinforce Rolland's (Reference Rolland1994) assertion that it is necessary to focus upon the biopsychosocial implications of conditions such as dementia, including their duration, course, level of incapacity and impacts, rather than solely on diagnosis, in order to assist families and individuals within families to adjust.

There are limitations to this research. Firstly, most has focused on spousal couples, with minimal attention to the broader range of family relationships, even though a small body of research suggests that relationships within whole families are important (Sutter et al., Reference Sutter, Perrin P, Chang, Hoyos, Buraye and Arango-Lasprilla2014; Trujillo et al., Reference Trujillo, Perrin, Panyavin, Peralta, Stolfi, Morelli and Arango-Lasprilla2016). Secondly, to capture complexity, researchers must explore a range of family relationships (Fauth et al., Reference Fauth, Hess, Piercy, Norton, Corcoran, Rabins, Lyketsos and Tschanz2012; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Macmillan and Brown2012; Bielsten and Hellström, Reference Bielsten and Hellström2019). However, only a small number of studies have explicitly acknowledged the need for a whole-family focus (Roach et al., Reference Roach, Keady, Bee, Hyden, Lindemann and Brockmeier2014b; Esandi et al., Reference Esandi, Nolan, Alfaro and Canga-Armayor2018; Hutchinson et al., Reference Hutchinson, Roberts, Roach and Kurrle2020). Thirdly, as dementia is a progressive condition, relationships need to adapt and change, yet the majority of studies are cross-sectional, so are unable to truly capture the impact upon relationships (Hellström et al., Reference Hellström, Nolan, Nordenfelt and Lundh2007). Finally, existing research has primarily considered the experience of the most common forms of dementia such as Alzheimer's disease. Studies are required to address the possible differences in adjustment that arise from the psychosocial implications of less-common forms of dementia for family relationships.

Behavioural variant fronto-temporal dementia

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a particularly challenging, rare form of dementia most commonly affecting younger people (Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Skelton-Robinson and Rossor2003). The most common subtype is behavioural variant FTD (bvFTD) (Rascovsky et al., Reference Rascovsky, Hodges, Knopman, Mendez, Kramer, Neuhaus, van Swieten, Seelaar, Dopper, Onyike, Hillis, Josephs, Boeve, Kertesz, Seeley, Rankin, Johnson, Gorno-Tempini, Rosen, Prioleau-Latham, Lee, Kipps, Lillo, Piguet, Rohrer, Rossor, Warren, Fox, Galasko, Salmon, Black, Mesulam, Weintraub, Dickerson, Diehl-Schmid, Pasquier, Deramecourt, Lebert, Pijnenburg, Chow, Manes, Grafman, Cappa, Freedman, Grossman and Miller2011). Prevalence of bvFTD is low, however, the disease is highly significant due to its distinctive impact on the lives of those who experience it (Warren et al., Reference Warren, Rohrer and Rossor2013). BvFTD impacts upon social cognition, affecting theory of mind, empathy, awareness of the impact of bvFTD on oneself and emotional blunting. It also impacts upon aspects of cognitive function, including executive function, attention and concentration, insight and awareness. When combined, these changes have a significant influence on the behaviour of the person with bvFTD, including disinhibition, apathy and impulsivity (Rascovsky et al., Reference Rascovsky, Hodges, Knopman, Mendez, Kramer, Neuhaus, van Swieten, Seelaar, Dopper, Onyike, Hillis, Josephs, Boeve, Kertesz, Seeley, Rankin, Johnson, Gorno-Tempini, Rosen, Prioleau-Latham, Lee, Kipps, Lillo, Piguet, Rohrer, Rossor, Warren, Fox, Galasko, Salmon, Black, Mesulam, Weintraub, Dickerson, Diehl-Schmid, Pasquier, Deramecourt, Lebert, Pijnenburg, Chow, Manes, Grafman, Cappa, Freedman, Grossman and Miller2011; Warren et al., Reference Warren, Rohrer and Rossor2013). As a consequence, bvFTD brings unique challenges for the person with the diagnosis and their family, including partners, adult children, siblings, children and young people.

Studies have highlighted early and ongoing changes in relationship quality and associated distress (Massimo et al., Reference Massimo, Evans and Benner2013; Oyebode et al., Reference Oyebode, Bradley and Allen2013; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Hellzen, Stordal and Enmarker2019; Thorsen and Johannessen, Reference Thorsen and Johannessen2021). Furthermore, some studies have emphasised that family members experience significant changes in roles and identity because of the impact of bvFTD (Massimo et al., Reference Massimo, Evans and Benner2013; Nichols et al., Reference Nichols, Fam, Cook, Pearce, Elliot, Baago, Rockwood and Chow2013; Thorsen and Johannessen, Reference Thorsen and Johannessen2021). Although this is also the case for other forms of dementia, in bvFTD these changes are suggested to be more severe, occur earlier in the course of bvFTD and, when combined with the significant behavioural changes, create particular challenges for family members (Hsieh et al., Reference Hsieh, Irish, Daveson, Hodges and Piguet2013; Mioshi et al., Reference Mioshi, Foxe, Leslie, Savage, Hsieh, Miller, Hodges and Piguet2013; Oyebode et al., Reference Oyebode, Bradley and Allen2013; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Hellzen, Stordal and Enmarker2019). Few studies have explored the experiences of people living with bvFTD directly (Avineri, Reference Avineri, Mates, Mikesell and Smith2013; Griffin et al., Reference Griffin, Oyebode and Allen2016) and further research is needed to elicit their perspectives.

Studies of bvFTD have suggested that multiple factors (relationships, coping strategy, mood) may influence the outcomes associated with care-giving (Diehl-Schmid et al., Reference Diehl-Schmid, Schmidt, Nunnemann, Riedl, Kurz, Förstl, Wagenpfeil and Cramer2013; Mioshi et al., Reference Mioshi, Foxe, Leslie, Savage, Hsieh, Miller, Hodges and Piguet2013). There have been conflicting results concerning the efficacy of problem-focused and emotion-focused coping (Wong and Wallhagen, Reference Wong and Wallhagen2014; Roche et al., Reference Roche, Croot, MacCann, Cramer and Diehl-Schmid2015). It is not clear how any of these factors change over time, in the context of family dynamics and the developmental trajectory of bvFTD.

Accordingly, there is a clear need for research which focuses on family relationships, because a range of family members including the person with dementia are affected. Attributes such as awareness, reciprocity and empathy are important in relationships (Cox, Reference Cox2009). However, in bvFTD, these are fundamentally affected. Consequently, research which considers the reciprocal relationship between bvFTD and family relationships over time, and which includes the person living with dementia, is critically important.

Objectives of the research

We sought to develop an in-depth, detailed understanding of the intergenerational family experience of bvFTD over time. In this article we focus on two of our research questions:

(1) How were family relationships experienced prior to bvFTD occurring?

(2) How has bvFTD affected and impacted upon family relationships over time?

Method

We adopted a qualitative longitudinal approach, guided by constructivist epistemology, to reflect the many different and valid realities among the individual family members (Kendall et al., Reference Kendall, Murray, Carduff, Worth, Harris, Lloyd, Cavers, Grant, Boyd and Sheikh2009). Our analytic approach was pluralistic because of its potential to provide a rich, detailed understanding through multiple perspectives (Lal et al., Reference Lal, Suto and Ungar2012). We chose Narrative Thematic Analysis (NTA) and Grounded Theory (GT) (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006; Riessman, Reference Riessman2008) because of their mutual complementarity and the valuable perspectives that they bring to our topic. Narrative methods are particularly useful in examining the way in which ill-health and disability disrupt identity and everyday lives (Frank, Reference Frank1995). Given the critique of Riessman (Reference Riessman2008), we did not limit ourselves to what was being said and collaboratively constructed within an interactional context. We also considered how the narrative illuminated the ways in which families described their relationships with other family members, the meanings they held about these relationships and how these narratives were communicated. Similarly, Constructivist Grounded Theory (CGT) involves an interpretation of how and sometimes why participants construct meanings and act in particular ways (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006). We used CGT to explore the ways in which family members conceptualised bvFTD and the strategies they used to manage the impact of bvFTD on their lives.

Recruitment

We purposively recruited families, who were the unit of study, to reflect a range of experiences across the trajectory of the condition, including those living at home and in a care home setting. Exclusion criteria were:

• A diagnosis of a pre-existing neurological condition except for motor neurone disease which has known associations with FTD (Lillo and Hodges, Reference Lillo and Hodges2009).

• Families where interpreters would be required.

• Children aged 6 or below.

We used a combination of purposive and snowball sampling to recruit families living with bvFTD from National Health Service (NHS) services. In each family, the person with bvFTD had received their diagnosis from an NHS dementia service. The person with dementia and/or their closest family member were the first contact point. They decided who was considered to be family and which members were to be approached to participate.

Data collection

JLF conducted semi-structured narrative, biographical interviews with family members every six to nine months over three time-points in their own home, between 2012 and 2014 (Hollway and Jefferson, Reference Hollway and Jefferson2013). Reflections on early interviews resulted in the adoption of techniques from the free association narrative interview method, to assist in revealing family experiences of life as it is lived, as well as reflecting on their lives (Hollway and Jefferson, Reference Hollway and Jefferson2013). We conducted interviews together and/or separately, determined by the wishes of those taking part. Families were involved over 14–24 months, resulting in a total of 46 interviews lasting 19–97 minutes. We used observational and field notes as additional data sources (Riessman, Reference Riessman2008).

In initial interviews, we explored the nature of family relationships, families' understanding of and experience of living with bvFTD, and the strategies used to cope with these experiences. In subsequent interviews, we continued to focus on these areas, with attention to changes since the last interview. We included additional questions to address specific issues raised in earlier interviews with that person, dyad or family. To preserve confidentiality within families, we did not discuss or explore information obtained during interviews with one member of a family, with other family members.

Ethics

The study received approval from the NHS research ethics committee West Midlands–the Black Country. All participants gave written informed consent. However, consent was viewed as an ongoing process and clarified at each contact (Hellström et al., Reference Hellström, Nolan, Nordenfelt and Lundh2007). Furthermore, a research diary was kept by JLF and was discussed with the two co-authors in supervision, to ensure consideration of participants' rights. Ethical mindfulness was adopted (Warin, Reference Warin2011; Bowtell et al., Reference Bowtell, Sawyer, Aroni, Green and Duncan2013) and was particularly necessary given the longitudinal research design, as families can become dependent on researchers (Holland et al., Reference Holland, Thomson and Henderson2006). This involved engaging in research and personal supervision, reflection during and after interviews, offering debriefing with participants, requesting feedback at the end of interviews and providing relevant information such as available support services. Furthermore, strategies were designed to ensure appropriate endings to the research relationship with the families, including addressing support needs throughout their involvement in the research, gaining feedback on their experience of participating and providing feedback about how the research was being disseminated and used. The final contact with participants was structured to explore their experience of being involved, to identify any further support needs and provide feedback on the findings.

Analysis

JLF undertook all analysis with supervision and guidance from the co-authors. All interviews were transcribed verbatim. Each was listened to and read multiple times to achieve immersion in what was said and how it was expressed, with reference to field notes. Transcripts were annotated to reflect tone of voice, significant moments, pauses or gaps. Electronic versions were uploaded into NVivo 10 (QSR International, Melbourne). The process of analysis was iterative, working between and within families, between time-points, and between NTA and CGT approaches.

NTA involved thematic coding, with attention to the context in which the narrative theme was framed. Where joint interviews were analysed, care was taken to identify who was narrating and whether it was a shared or individual narrative. Where more than one interview within a family was undertaken, themes were compared to develop a thematic structure for the family narrative, acknowledging similarities and differences in perspectives (Gubrium and Holstein, Reference Gubrium and Holstein2009; Esin, Reference Esin and Frost2011). Following completion of interviews at all three time-points, narrative moments for each individual and then each family were reviewed and brought together to form an overall narrative thematic structure for each family, which preserved similarities and differences in perspectives. Finally, comparisons across all families occurred, to identify super-ordinate themes and subthemes. Transcripts were revisited to verify thematic structure and refine analysis, after which we produced an integrated narrative of how bvFTD had impacted on family relationships.

The process of CGT was informed by Charmaz (Reference Charmaz2014), although due to the heterogeneity within the sample, theoretical saturation was not sought, and theory building was very limited. Analysis began with initial open coding of each of the individual family interviews, on paper copies of their transcripts, concentrating on gerunds which highlighted actions and processes (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006). This informed subsequent interviews with families, thus working towards theoretical sensitivity (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006). Reflections on coding within and across families were noted, to guide the interview process. JLF then carried out open and focused coding exploring the data incident by incident in NVivo 10. Each individual interview was coded separately and then brought together as a family unit on a spreadsheet as described for NTA. This allowed for the development of focused codes within families as the unit of study. The results of analysis for each of the families were not brought together until after analysis of all three time-points. Memos were used to support thinking and memos and coding structures were used to inform the areas of inquiry for subsequent interviews.

Enacting the two methodologies was a cyclical process, moving fluidly between each form of analysis when considering each transcript, each family and when bringing the results together. This is reflected in the Results section, where the NTA is foregrounded in the presentation of the pre-existing relationship and relational outcomes, and the family experience of bvFTD that was illuminated by GT is used where appropriate to illustrate how these outcomes are enacted within the family.

Results

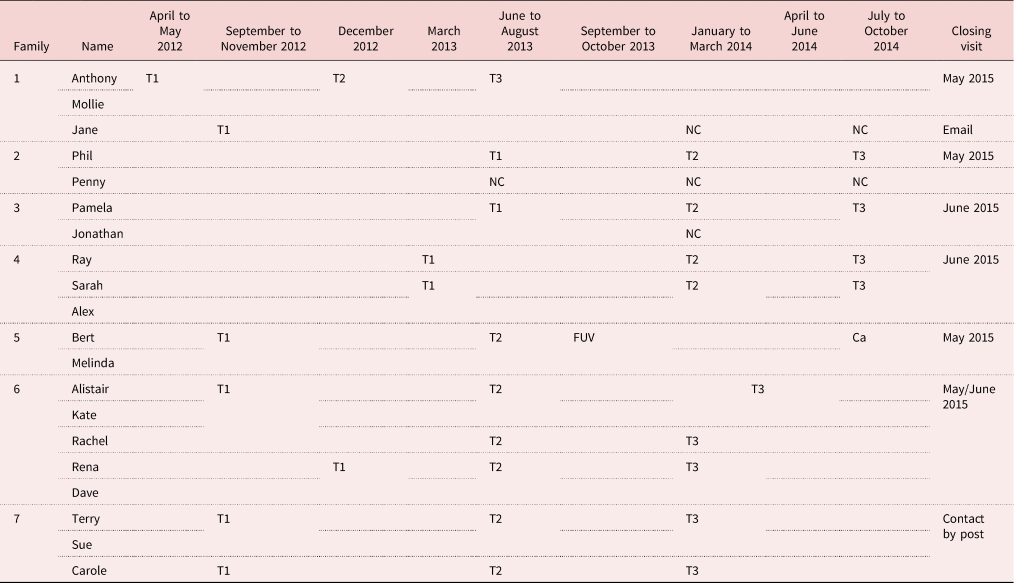

Seven families took part, with one to five members participating in each family, including five of the seven people living with bvFTD. The person with bvFTD in Family 2 (F2) was unable to participate due to her degree of frailty and the daughter of the person in F3 was not willing for her mother (with bvFTD) to be approached, citing the mother's denial of her diagnosis. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the sample and Table 2 shows detail of the interviews conducted.

Table 1. Research participants

Notes: 1. Person living with behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD). 2. Person living with bvFTD did not participate. T1: time-point 1 interview. T3: time-point 3 interview.

Table 2. Interview map

Notes: T1: time-point 1 interview. T2: time-point 2 interview. T3: time-point 3 interview. NC: no contact. Ca: cancelled by participant. FUV: follow-up visit.

The seven families included five people living with bvFTD, five partners, five adult children, two sons-in-law and two parents-in-law. Time from first noticing symptoms to diagnosis ranged from one to eight years. All but one had developed symptoms under the age of 65 years, although three persons were over 65 years by the time of the first research interview (F3, F5 and F7). Time since diagnosis ranged from two to five years at time-point 1. The majority of participants living with bvFTD and their closest relative were in receipt of services at the beginning of the research but not all continued to receive support over its duration. All participants were of white European ethnicity.

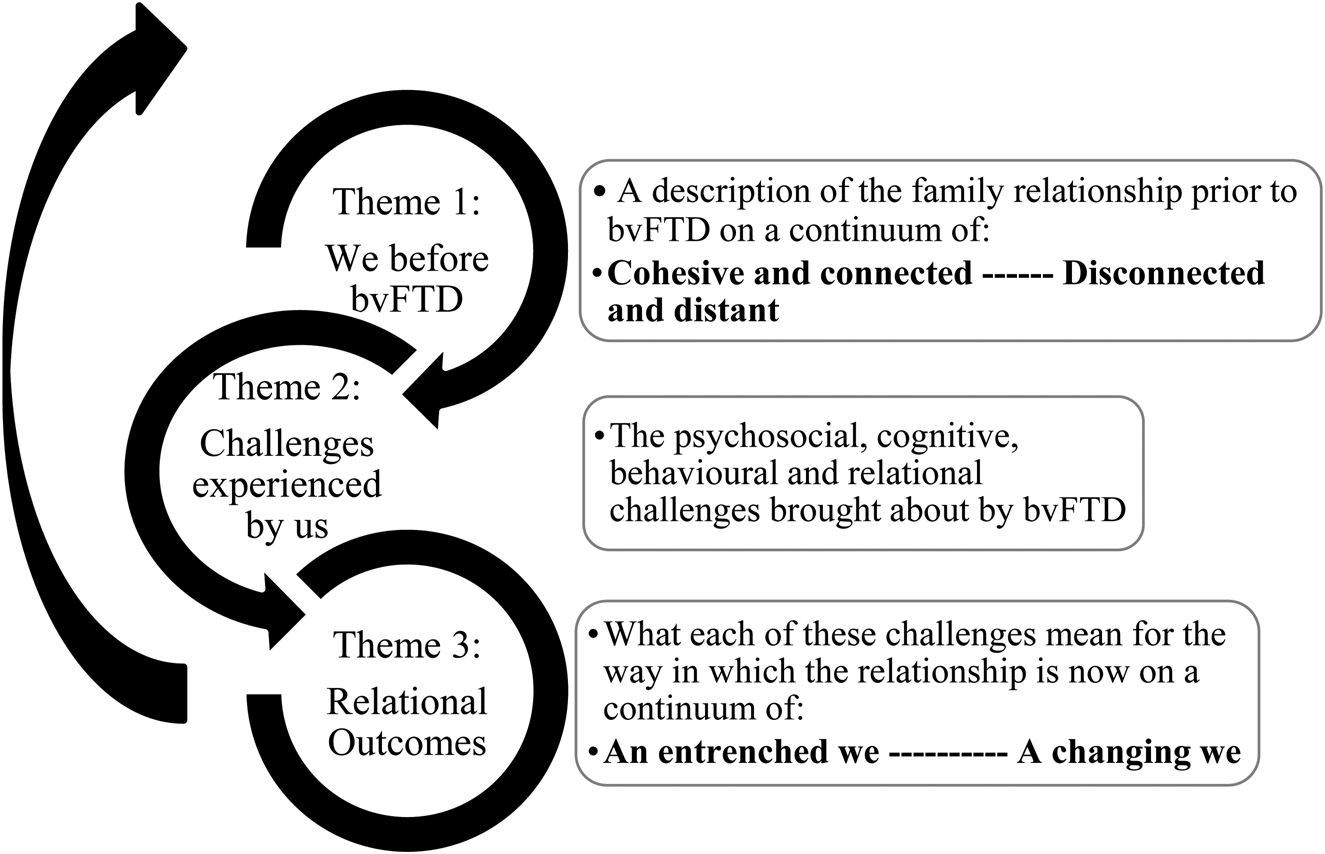

Three super-ordinate themes illustrate the findings pertaining to the research questions described earlier (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overview of super-ordinate themes.

Note: bvFTD: behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia.

As illustrated, these three themes exert a reciprocal and cyclical influence on each other. The results presented here illustrate the experience for close and wider family members including the person living with bvFTD. Individual experiences and perspectives, and further detail concerning families' coping strategies will be addressed in separate articles.

Super-ordinate Theme 1: We before bvFTD: cohesive and connected – disconnected and distant

These families' relationships were characterised as existing on a continuum from cohesive and connected to disconnected and distant. Two families, at different points on this continuum, are described below to evidence this super-ordinate theme.

F5: We are family, close and interconnected lives

Bert and Melinda were the only members of their family to participate. Their role as parents and grandparents seemed to be central to their lives and they talked about regular, frequent contact with their children and grandchildren, e.g. having daily contact with one of their grandsons:

Melinda: He's two. He's adorable, and he's so good … We have him at least an hour a day, don't we, because he's so funny. You can be feeling really down, and this little chap comes in and he's just incredible…

Bert: If he wants something he comes and grabs my hand. (Time-point 1 (T1))

The couple appeared to have in-depth knowledge and understanding of each of their children and grandchildren:

Melinda: And these are all incredible kids, and he's the eldest. He's 41, here, the head of the family, really … He's always there for them, isn't he?

Bert: Yeah, the trouble is, the eldest one … they just assume that role, don't they? Your brother did in your family, didn't he? (T1)

Bert and Melinda seemed to suggest they were a close-knit family, valuing their children as individuals in their own right and having a strong sense of their worth. This appeared to guide their role within the family, seeing themselves as there to support their children. However, this did not preclude reciprocity as they expressed how supportive their children were to them too. They described periods of considerable adversity in their lives, which they managed together, supporting each other through difficult times. Open communication, tolerance, understanding and acceptance of each other and their individual needs appeared central to their way of coping:

Interviewer: How would you say, as a family, you cope with adversity?

Melinda: I think one thing we all have is we accept each other for what we are. Every child or young person are individuals, and we don't say, ‘Because he's like this, he should be like that’. (T1)

In this context, family relationships appeared to be of considerable importance to the couple and were central to their lives together.

F3: A distant and disconnected relationship

In this family, the daughter (Pamela) and son-in-law (Jonathan) participated, but Pamela's mother Elizabeth, who was living with bvFTD did not. The couple described a relational history with Elizabeth that had been dominated by distance and disconnectedness. Specifically, Pamela described events surrounding her emergence into adulthood which were marked by a sense of abandonment by her mother at a time when she felt vulnerable and needed support:

And I suppose as a family we disintegrated when my mum and dad divorced … But it was a bit like, for her, to get to that situation where she could split from my father, it was a bit like ‘Oh! I've got to get rid of all the kids so that I can then do what I want’ … And I happened to be (laughs) going out with someone that I'd met, and I ended up getting married at 18. Which lasted all of … 18 months … both my mum and dad said ‘Ooh no. You stay in your house. You can't come and live with us’ … So when I think of [my son], at his age, there is no way that I would close that door on him and say ‘No, you're not coming back’ … And I can't understand that. But that is why I say, my relationship with my mother is as it is… (Pamela, T2)

As a result, she came to see her mother as self-serving, a view that Jonathan appeared to share:

But she's always had her own way and she's never been satisfied, all the time I've known her, even when she didn't have what she's got now, we don't think … but she always very much wanted her own way didn't she?’ (Jonathan, T3)

In this context, the couple described their relationship with Elizabeth as being distant and based on duty rather than an emotional connection. They further described unsatisfactory contact and a sense that they were on their own:

Jonathan: We weren't close. She … used to cook Sunday lunch once a fortnight. So we would go with [our son] … and that was really the only time we saw her except when we'd get a phone call midway through Sunday afternoon on a Sunday where we weren't going for lunch and she'd say, ‘Is it all right if we come round to see [her grandson]?’

Pamela: So she'd come round for quarter of an hour, have a cup of tea and then go. I mean that's like we'll just slot him in.

Jonathan: It was never a close [relationship] … we never felt particularly supported and she didn't seem to want our support, did she? (T1)

Where closer and sustained contact with Elizabeth had been required in the past, Pamela equated this with feelings of being ‘sucked dry’. Therefore, prior to bvFTD, it appeared that the couple did not find their relationship with Elizabeth meaningful, had the minimum contact necessary and found these boundaries important in their relationship with her.

As these narratives illustrate, each family described a unique relational history. It is nevertheless important to recognise that accounts of the relationship frequently differed between participants within the same family, particularly those of the person living with bvFTD compared with other family members. This therefore highlighted differences in the meaning and perception of relationships between individuals and generations within each family.

Super-ordinate Theme 2: Challenges experienced by us

In the context of these pre-existing family relationships, bvFTD generated particular challenges. Families described how bvFTD impacted upon a range of functions including features of social cognition such as empathy, interpersonal relating and perspective taking. For example, this quote from Melinda highlighted difficulties with social cognition:

He's lost his temper in shops … Because normally, before we go out to do anything, we go over what we're going to do, what we've got to look for and I'd forgotten to tell him about unreeling the cable and he lost it in Wilkinson's. And this gentleman came to try and help him and he was really abusive to him … and all sorts. (F5, T1)

Bert appeared unable to monitor and modify his behaviour according to social norms and consider how his actions might impact upon others. Similarly, Carole (F7) described how her concerns about her father's lack of self-control in what he said to others resulted in her limiting her parents' participation in family events such as her daughter's party:

So a lot of the time I don't invite mum or dad … and I feel guilty then that I'm not including them in what normal grandparents would be included in but it worries me what he's going to be like … what he's saying to people and thinking. (Carole, T1)

All seven families gave examples of changes in social cognition, commonly reported as beginning before diagnosis and becoming more problematic over the duration of the research. They emphasised the difficulties these changes brought for family and social relationships, for everyday interactions and for employment. These changes were more apparent to those living with or in regular and frequent contact with the person with bvFTD. Wider family members were less likely to be aware of the changes, leading to conflict in some families. For example, Sarah and Alex (F4) explained that her aunties denied that her father had dementia:

That's why we find it difficult I think with some of the family members: they don't believe he's got it. And we say, ‘You don't live with what we see and hear’. And I've had a chat with his sister here … and she said, ‘I don't think he's got dementia’. And I said, ‘You don't see it’. (Alex, T1)

This lack of awareness may arise because changes are initially subtle or may not correspond with the symptoms people commonly associate with a diagnosis of dementia, such as memory loss.

Changes in executive function, including planning, initiating, monitoring and stopping behaviour as well as impulse control, processing and sense-making, judgement and decision-making were also described. For example, Sue (F7) illustrated how Terry had been unable to clean the shower, suggesting difficulties with planning, sequencing and monitoring his actions:

I said this shower needs cleaning … So I said ‘Would you do it for me?’ … and I left him. I said ‘I'm not going to interfere, you don't like me interfering’. And I had all of the things for what it's needed and other things. And he was squirting the bathroom cleaner on the tiles with this grouting brush, but no water. And he says to me ‘This cleaner has fumes’. (T2)

Similarly, other families described circumstances in which the person living with bvFTD was no longer able to carry out activities, including complex tasks associated with their work, operating everyday appliances such as the microwave and cooker, or managing buttons and zips. These changes created considerable challenges for the person living with bvFTD in managing everyday life, resulting in loss of employment, difficulties with independent activities and increasing levels of dependence on others for wellbeing to be maintained, as reflected in Anthony and Mollie's narrative:

Mollie: I find that when we were away in May … that [he] was looking more to me for sort of, instruction.

Anthony: Instead of taking the lead I was just…

Mollie: You were looking for instruction weren't you.

Anthony: I was the crew and you were the captain … A role reversal. (F1, T3)

Furthermore, as the quote from Anthony implies, it appeared that this reliance involved emotional dependence, as bvFTD compromised his ability to feel secure and in control. Terry powerfully illustrated how challenging it was for him feeling out of control:

But there's all these factors that's come on, which makes me a zombie … and I don't want to be like that, but it's out of my remit, isn't it? It's like something that's chipping away, which I can't get back … Because I ain't like that … But it's sad in a way, isn't it, very sad, but as I say, I can't do nothing about it. If I could read up about something and do something, I'd do it, whenever. But as I said, it's gone, the brain's all gone and what can you do? (F7, T3)

Consequently, it became evident that the specific nature of the effects of bvFTD created a significant disruption to the functioning of the person with bvFTD, particularly regarding social cognition and managing complex tasks. Close family members in particular felt that the person was less able to contribute to the everyday work of family life, resulting in increasing levels of responsibility for them. Characteristics of the person that were previously valued, including empathy, reciprocity, care and interpersonal sensitivity were also perceived to have changed. BvFTD had a profound impact on the lives of the person with dementia and their family.

Super-ordinate Theme 3: Relational outcomes: a changing we – an entrenched we

This third super-ordinate theme involved relational outcomes on a continuum from ‘a changing we’ to ‘an entrenched we’. Through looking at relational outcomes, we aimed to capture the relational transitions that families and individual family members underwent over the duration of the study. The use of the term outcomes is not to imply an end-point, rather it illustrates the relational positions of these seven families by the end of data collection. Specific and distinct outcomes were evident for close family members, including the person living with bvFTD, partners, adult daughters and their partners, and wider family members.

Relational outcomes for close family members

Close family members experienced considerable changes to their relationships as a consequence of the interplay between the effects of bvFTD and their prior relationship. Two couples (F1 and F5) were able to accept and adapt to the changes, suggesting that their relationship had become stronger in a different way. In this context, collaboration between the person with bvFTD and their partner characterised their coping, along with an explicit acknowledgement of the need for the care partner to increasingly take responsibility to support the wellbeing of the person with bvFTD, as well as managing everyday life. In one family, this collaboration included their wider family. In this context, partners sought ways to understand bvFTD and its impact and work with the person with bvFTD to master the challenges they faced and maintain their strong bonds, while acknowledging the ongoing changes to the relationship. In the following excerpt, both Bert and Melinda openly discuss the fundamental changes wrought by altered social cognition and how they have learned to accept Bert's disinhibited behaviour (referred to as ‘childish’):

Bert: It's like having a new head on, isn't it.

Melinda: Yeah. That's what I said to you, I've had two of you.

Bert: …it's like having your head took off and another head put on it. You know the changes that happen.

Melinda: Because we can have some quite childish behaviour at times.

Bert: You can't do anything about it at the end of the day. It just becomes part of you, doesn't it?

Melinda: I think once you accept that this is part of you and once everybody else accepts, well, this is a learning experience, it's a new way … I think that's when it becomes a lot easier. You know, I think it's just saying, well, you can't change it, it's learning to cope with it. (F5, T2)

In both couples, the strategies used were reflective of characteristics of their pre-existing relationship such as open communication, even where this involved difficult conversations. Both families drew upon their internal resources, including seeking support to find ways to cope. Both couples therefore sought ways to have a meaningful life, albeit different from their previous relationship. This was not without its challenges, because the partners shouldered the majority of responsibility for making such mutuality possible due to the impact of bvFTD on the person's empathy and self-control. For example, one couple (F1) felt forced to give up their main hobby, due to the person with bvFTD becoming less able to inhibit aggression:

And that was the biggest thing really, was confidence and aggression as well. That was the other thing that we tended to get very aggressive with other boaters, the ones who like watching paint dry coming through… (Anthony)

However, they commented that they had found another way to continue their interest and that they had become stronger together because of these changes:

Anthony: The important thing [is] that we work together as a team. We're not two separate people.

Mollie: Yeah. He still keeps me in my place. He keeps me, not down sort of thing, but … how can I put it? You're a good influence, aren't you. (T3)

In two other families, close family members (one partner (F2) and one couple (F6)) described significant changes in both social cognition and executive functioning, which caused loss of the relationship as it was. While losing ‘we’, these family members remained strongly connected, although the nature of connectedness had fundamentally altered from an intimate, close partnership to carer and cared for. For example, in their joint interview at the beginning of the research, Alistair (F6) identified that his relationship with Kate had become more like brother and sister. They both acknowledged the loss of intimacy that resulted from Alistair's loss of empathy, and the way this changed their togetherness. By the third joint interview, Kate described her relationship with him as more like mothering:

I think it's more like … I tend to be more mothering, yeah more mothering. It's because we went through like the brother and sister bit, [he] was still my friend, I could still confide and talk to but because there's no empathy … and because so much more responsibility is mine now for simple decisions … all of it tends to be mine, I feel more as if I'm mothering … When anything happens it's down to me to sort or me to organise … and everything stops with me. (T3)

Similarly, Phil (F2) described how intimacy and closeness with Penny had fundamentally changed and that, as a consequence, his ongoing commitment to his wife reflected his responsibility to care for her.

Two further close family members described a loss of togetherness as a consequence of the changes in empathy bvFTD had wrought in the person diagnosed, in the context of a previously close and supportive relationship (one adult daughter, her husband and father (F5); one couple (F7)). In both families, those closest to the person with bvFTD seemed unable to accept or tolerate the changes and positioned the person with the diagnosis as the problem. For example, in F7, Sue and Terry participated in joint interviews throughout the research. Sue reflected on the value of their previous togetherness and how this had changed since bvFTD had led to Terry losing the ability to empathise

Sue: I just feel that it would be nice to have a bit of affection, so he'd do something for me and [I would] think, ‘Oh that's nice … that's a nice thought’ … It's always I've got to say it. Like the other day, I said, ‘We'll have a bit of lunch on my birthday’, and he said, ‘Oh that's a good idea’, but he wouldn't think of that.

Interviewer: And that sort of links to what you were saying about not having that compassion anymore?

Terry: Yeah, that piece is missing out of the jigsaw puzzle. I can't help that.

Sue: Oh it's [her] birthday, I've got to organise something for her birthday’, I don't get anything like that, nothing, not even a cup of tea in bed.

[…]

Terry: But that is part of the symptom, isn't it?

Sue: Yes. (T3)

While Sue acknowledged Terry's assertion that these changes are part of his illness, emotionally she seemed to struggle greatly with them. Indeed, when close family members in either of these families (F4 and F7) talked about the difficulties they experienced, their tone of voice often reflected frustration and anger with the person living with bvFTD. It seemed that both persons living with bvFTD were often positioned as the problem and their behaviour interpreted as deliberate. Indeed, Sarah (F4) suggested everything her father had previously been to her had now changed for the worst as a result of his illness and behaviour.

Therefore, for these two families, their interpretation of the changes brought by bvFTD, and the meanings they ascribed to them, resulted in a sense of loss of the person as they had previously been. BvFTD also brought fundamental changes to relationships which caused those closest to the person with bvFTD to feel they were losing ‘we’. Therefore, family members, including the person with bvFTD, frequently acted independently from each other in order to address their individual needs.

Finally, as previously discussed, Pamela and Jonathan (F3) experienced a prior relationship characterised by disconnectedness. BvFTD disrupted the carefully maintained boundaries as this family felt they had to come closer together to support Elizabeth, which then caused further damage to their relationship with her. They also seemed angry and frustrated and appeared to position Elizabeth as the problem. While they acknowledged she had bvFTD, they largely appeared to perceive her impaired social cognition as an exaggeration of existing personality traits, therefore holding Elizabeth responsible for the challenges they faced. Further distancing in their relationship occurred over the duration of the research. By the end of their involvement in the research, her daughter reflected that she no longer felt she had a relationship with her mother:

I haven't got [a relationship with her]. It sounds awful but I don't want to see her, I don't want to do anything for her. (T3)

By this point, they avoided contact, engaging in an intensive care management role and keeping direct care delivery to a minimum. They expressed the view that they would only be free of their involvement with Elizabeth when she died.

Relational outcomes for wider family members

A changing we

In the context of a prior relationship involving cohesion and connectedness, two families worked together with wider family members to address the changes and facilitate the continued involvement of the person with bvFTD in their lives (F5 and F6). Family members typically learned about bvFTD and engaged in mutual support to address emotional and practical day-to-day needs. In F6, Kate, her parents and Rachel described drawing closer to support Alistair in tackling the apathy that can be associated with bvFTD, something that he appeared to value (F6):

Kate: So my dad's back round again driving things forward and…

Alistair: Keeping me motivated. (T3)

When Kate was at work, Rachel often used to call to see her father, because she knew Kate struggled with Alistair being alone at home:

She doesn't like to leave him on his own for any length of time at all. So, if she's going out for the evening, I'll pop round and have a chat and stuff. I don't think he likes to be on his own either. (T3)

In both families, examples of connectedness and support were evident throughout their involvement in the research. Nevertheless, increased closeness had consequences including exposure to loss and sadness and disruption to the family lifecycle. For example, Rena and Dave (F6) reflected on the impact of bvFTD on Kate and Alistair's relationship and their increasing reliance on them:

Dave and I are too old to take him on. And Kate doesn't expect us to but she is only 53. She's got a few years that she's got to work and financially she'll need to work. So, what happens to Alistair? He doesn't like her not being there. He can cope if Dave's there, but he doesn't like her not being there. So how is that going to work? I think that's what scares us all. And there isn't an answer. (Rena, T3)

Alistair and Kate's wider family circle shows a constellation related to the younger onset of bvFTD, in that the generation above are involved in support for the couple. Relationships in these two cohesive families appeared to become even closer as they worked together to address the challenges imposed by bvFTD. However, while it is evident that they gave willingly of their support, they also experienced distress, sadness and fear for the future as they recognised the limits of their ability to help.

An entrenched we

Five families experienced ruptures in their relationships with wider family members, leading to entrenched positions, resulting in increased conflict, drifting apart or in some cases losing we (F1, F2, F3, F4 and F7). In all five families, these ruptures were influenced by previous ways of relating, apparent lack of understanding of each other's experiences and, in some, lack of congruence in awareness and understanding of bvFTD and its impact.

For example, although Mollie and Anthony (F1) described being a very close couple, they did not describe relationships with their wider family as being central to their lives. Their description of their relationships with their respective adult daughters suggested emotional distance, limited communication and unmet expectations. When they received the diagnosis of bvFTD, they appeared to have minimal communication with their children about the diagnosis to help them understand. Rather, they provided them with written information:

Well, with … immediate family, we've managed quite well because what I did was … go on to the Alzheimer's site and on there it gives about [his] dementia and I printed some off and I handed them out to them. (Mollie, T1)

Subsequently, as Anthony's needs increased, the couple described further difficulties in their relationships with their daughters, suggesting neither of them understood what was happening and that this had caused conflict. For example, they discussed one daughter's lack of understanding:

Mollie: She's seen all the pages … she's been on the website … (sighs) I think it's just a dig because we weren't … she didn't get that attention at the time. (T2)

Anthony: [She's] very much a ‘me’ person. It's all ‘me, me, me’ and anything else is totally oblivious to regardless.

Mollie: You're useful to her and if you're not useful. (T3)

The couple appeared upset with their daughters and seemed to position them as at fault. They did not appear to have considered that it might be difficult for their respective daughters to understand the complexity of the changes or that they might be experiencing grief at the impact of bvFTD. Ruptures were evident in all five of these families, reflecting difficulties these families experienced in collaborating to address the challenges and conflicts that arose. These ruptures resulted in some participants describing a sense of isolation, conflict or a loss of relationships with other family members.

Discussion

This research is one of a few studies to have considered the whole family experience of living with dementia, although none has previously focused on bvFTD. A focus on bvFTD is important because of its impact on social cognition, affecting such attributes as empathy, reciprocity and awareness, all of which contribute to relational functioning. Consistent with existing research, our results illustrate the value of taking a whole-family approach to understanding the reciprocal interplay between bvFTD and family relationships (Roach et al., Reference Roach, Keady, Bee and Williams2014c; Esandi et al., Reference Esandi, Nolan, Alfaro and Canga-Armayor2018; Hutchinson et al., Reference Hutchinson, Roberts, Roach and Kurrle2020)

Our research identified three super-ordinate themes. The first, ‘We before bvFTD: cohesive and connected – disconnected and distant’, represents the bedrock of pre-existing family relationships upon which family members, together, between generations and individually, faced the experience of bvFTD. This categorisation of the continuum should not be taken to imply that relationships are either good or bad. Rather, the aim is to illustrate the relational characteristics that influenced how these seven families attempted to make sense of and cope with the diagnosis and its impact upon their relationships.

In some families, patterns of relating suggested a capacity for open communication, collaboration and cohesion as well as managing conflict when this arose. These families' articulation of their relationships suggested that they had been able to draw upon internal resources to address adversity and challenge in the past. In other families, although cohesion and collaboration appeared strong in the prior relationship of the person with bvFTD and their closest family member, communication and collaboration between generations and extended family members was less evident and, in some cases, past conflicts remained unresolved. Furthermore, within some close and wider family relationships, maintaining distance appeared to be necessary to manage their experience of a difficult and disconnected relationship, in which poor communication and limited conflict management occurred.

Our findings are consistent with existing theory concerning the core features of family relationships (cohesiveness, conflict management, communication style, adaptability, role flexibility) (Kissane and Bloch, Reference Kissane and Bloch2002); and with research showing that these features influence how families address illness, disability and loss, and then this experience, in turn, impacts upon their relationships (Rolland, Reference Rolland1994, Reference Rolland1999). As Rolland (Reference Rolland1994) and others have emphasised, to understand how a family may address the challenges brought by illness and disability, we must have a clear picture of their strengths and vulnerabilities. Family-oriented assessments can assist practitioners to understand how effectively a family is able to work together and use available support to address the challenges associated with such transitions.

Understanding the family context also requires knowledge of the lifecycle stage of the family system. As reflected in prevalence figures of bvFTD (Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Skelton-Robinson and Rossor2003), most participants with a diagnosis in this research were under 65 years at symptom onset and when they were diagnosed. Previous research has revealed distinct challenges related to the lifestage of the person with the diagnosis and their family, involving employment, housing and financial responsibilities, the care of younger and/or older family members, and individuation of younger adult family members as they approach adulthood (Roach et al., Reference Roach, Keady, Bee and Williams2014c). None of those with bvFTD in our sample had children still at home and the majority were recently retired, however, in their everyday family lives, several were negotiating relationships with adult children in their thirties, some of whom had young children of their own.

It is within this context that the second and third super-ordinate themes, ‘Challenges experienced by us’, and ‘Relational outcomes: a changing we – an entrenched we’, illustrate the specific and complex psychosocial challenges that bvFTD brought for these seven families and the resulting relational outcomes.

Our findings are consistent with existing research in highlighting that a central feature of the lived experience of bvFTD is the profound impact it has on the person's social cognition and behaviour. These changes created a significant, early and progressive impact upon the person's ability to engage in the relational tasks associated with everyday family life (Massimo et al., Reference Massimo, Evans and Benner2013; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Hellzen, Stordal and Enmarker2019; Thorsen and Johannessen, Reference Thorsen and Johannessen2021). In this context, roles and relationships between the person with bvFTD and their closest family members are challenged at a very early stage, with close family members commonly shouldering the emotional labour associated with family life involving reciprocity, communication and mutuality, as well as other responsibilities that may previously have been carried out with the person with bvFTD. Such changes are distinctly different when compared with other forms of dementia such as Alzheimer's disease, where it is suggested that continuing mutuality in relationships is possible, at least early in the condition (Colquhoun et al., Reference Colquhoun, Moses and Offord2019). The challenges brought by bvFTD for relationships can therefore be likened to the concept of ‘second-order change’ described in systemic theory (Davey et al., Reference Davey, Davey, Tubbs, Savla and Anderson2012), where transformation of the family system itself occurs as a consequence of bvFTD.

Our findings further indicate that changes associated with bvFTD, particularly loss of empathy, ripple outwards to affect the whole family, influencing relationships between close and wider family members as well as between close family members. Wider family concerns about disinhibited behaviour could place distance between grandparents and young grandchildren; and affected couples' time and energy available to support these adult children, e.g. by caring for grandchildren, was impacted by the untimely intrusion of dementia.

The quality of relationships prior to the onset of bvFTD appeared to be influential in the nature of relational change and whether there were ruptures in this context. For example, where families were cohesive and able to address adversity then it appeared that wider family represented a source of strength and closeness for close family members. However, in families who were less connected or where existing ruptures were evident, wider family members could become sources of further distress and conflict for close family members. Blame, particularly, emerged when family relationships became strained, towards the person with the diagnosis or wider family members. These findings echo other studies identifying the protective value of supportive families to primary care-givers of people with dementia or, alternatively, the increased experience of burden to primary care-givers where conflict and poor cohesion exists (Tremont et al., Reference Tremont, Davis and Bishop2006; Trujillo et al., Reference Trujillo, Perrin, Panyavin, Peralta, Stolfi, Morelli and Arango-Lasprilla2016; Deist and Greeff, Reference Deist and Greeff2017). However, it cannot be assumed that a previously positive relationship will guarantee adaptation to bvFTD, as consistent with previous research, two of our families experienced considerable grief in the face of the changes and a loss of the relationship as it was (Fauth et al., Reference Fauth, Hess, Piercy, Norton, Corcoran, Rabins, Lyketsos and Tschanz2012; Wadham et al., Reference Wadham, Simpson, Rust and Murray2016).

Additionally, the subtlety of changes and the unexpected nature of bvFTD-related changes in social cognition and executive functions made it difficult for family members who were less involved to be aware of or recognise them. As Rasmussen et al. (Reference Rasmussen, Hellzen, Stordal and Enmarker2019) suggest, this subtlety also made it difficult for close family members to explain these changes. The lack of a shared understanding of what is happening is probably further complicated by the lack of awareness that dementia can occur at a younger age (Carter et al., Reference Carter, Oyebode and Koopmans2018).

Therefore, varying degrees of relational change were evident, reflecting a reciprocal and cyclical interplay between existing familial patterns of relating, familial and individual capacity for adjustment and adaptation, as well as the extent to which the changes associated with bvFTD were understood and accepted within families.

Research and practice implications

While some advances in diagnostic practice and early intervention have occurred since this study was completed, it remains evident that bvFTD is poorly understood, early diagnosis is challenging, and further development of support and interventions for the person and their family are required (Tookey et al., Reference Tookey, Greaves, Rohrer and Stott2021, Reference Tookey, Greaves, Rohrer, Desai and Stott2022). Such developments are particularly needed in light of the deleterious impact of the measures instigated during the COVID-19 pandemic on families living with dementia. Evidence suggests this has caused further strain to relationships between persons with dementia and their primary care partners and a decline in wellbeing (Boutoleau-Bretonnière et al., Reference Boutoleau-Bretonnière, Pouclet-Courtemanche, Gillet, Bernard, Deruet, Gouraud, Lamy, Mazoué, Rocher, Bretonnière and El Haj2020; Losada et al., Reference Losada, Vara-García, Romero-Moreno, Barrera-Caballero, Pedroso-Chaparro, Jiménez-Gonzalo, Fernandes-Pires, Cabrera, Gallego-Alberto, Huertas-Domingo, Mérida-Herrera, Olazarán-Rodríguez and Márquez-González2022). It also seems possible that these measures have impacted upon frequency and quality of contact with wider family members.

The findings reported in this study illustrate that family systems approaches to working with families affected by bvFTD would provide a valuable direction for practice-based interventions. As identified earlier, within this context, the needs of families and individuals within families should be assessed within a family-centred framework as a prelude to intervention, ideally as a whole family (Rolland, Reference Rolland1994). Assessment tools such as the Family-AiD (Roach et al., Reference Roach, Keady and Bee2014a) need further research but may assist practitioners to incorporate systemic factors into their assessments.

The development of tailored family-centred interventions is required which take into account familial patterns of relating, existing beliefs concerning health and illness, as well as conceptualisations of bvFTD. Research evidence and theoretical frameworks already exist which support the value of family-oriented, flexible interventions in the fields of cancer (Kissane and Bloch, Reference Kissane and Bloch2002), illness and disability (Rolland, Reference Rolland1994). Furthermore, the New York University (NYU) intervention for family care-givers of people with dementia has proven success in delivering family-focused interventions (Gaugler et al., Reference Gaugler, Reese and Mittelman2016). However, these need further research to assess their applicability to families living with bvFTD to ensure treatment integrity and application to practice (Benbow and Sharman, Reference Benbow and Sharman2014).

Our findings point to the need to provide specialised information concerning bvFTD. While information already exists, this is frequently focused on symptom description. Given the complex impact of bvFTD, this needs to be extended to incorporate the impact of bvFTD on everyday life. Furthermore, Pozzebon et al. (Reference Pozzebon, Douglas and Ames2016) suggest that spouses frame their experience of dementia within a relational context. It is therefore within a relational framework that information provision needs to address the nature of the changes in order to provide families with a conceptual understanding of bvFTD and how this relates to the person's behaviour on a day-to-day basis. Utilising a research-based approach to development alongside involving families affected by bvFTD as co-researchers creates the potential to address what is needed as well as how it should be delivered. Such an approach should seek to address flexibly individual family needs and expectations, thus preventing information provision which is of no value or even harmful (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Henwood and Smith2016).

Strengths and limitations

It is hard to recruit families with conflictual or distant relationships and such perspectives have been less in evidence in qualitative studies exploring the impact of dementia on relationships. It appears that the seven families in this study do represent a range of relationships on this continuum. However, although we recruited families with diverse relationships, access to and recruitment of wider family members in some participating families was challenging and resulted in a narrower range of perspectives being heard. Some couples were reluctant to provide direct contact details of other family members and instead offered to approach them themselves. This most commonly resulted in limited participation from other family members. There may be many reasons for this, such as a desire to protect other family members, because of conflictual relationships or because they wished to influence the family narrative offered to the researcher. Others have described similar challenges (Mccarthy et al., Reference Mccarthy, Holland and Gillies2003; Kendall et al., Reference Kendall, Murray, Carduff, Worth, Harris, Lloyd, Cavers, Grant, Boyd and Sheikh2009). Such research has emphasised, as we have found, that it is important to account for the multiple perspectives that may exist in a family, with none having precedence over others when reporting the family narrative. Thus, it remains important to consider the symbolic meaning of similarities and differences within accounts during analysis, as well as the considerable influence the researcher has on the ultimate outcome of the analysis.

While the longitudinal design is a strength of the study, further research would benefit from exploration of the family experience over a longer period of time. Similarly, future research would ideally address the sampling limitations, including gender and age of the person with bvFTD; gender, age and nature of the relationship of their primary care partner and the inclusion of wider family members. Further studies are also required to consider the potential impact of bvFTD on diverse family constellations including those influenced by varied ethnicities or sexual orientation.

Finally, the inclusion of people living with bvFTD in this study is a particular strength, given that very few studies have explicitly addressed the lived experience of this form of dementia.

Conclusions

Families' prior relationships influenced their responses to the changes in social cognition and executive functioning that are core to bvFTD; and the impairments in social cognition and executive functioning in turn impacted on family relationships. This interplay between relational and dementia characteristics is particularly cogent in bvFTD, precisely because of its early impact on areas such as empathy and self-control, which are fundamental to reciprocity and mutuality. Such changes challenge family cohesiveness. How families cope depends on whether close members have the psychological, practical and material resources to take on the emotional labour involved in sustaining closeness and on whether wider family can be drawn upon for strength and support or whether they sap energy through conflict. Whether families are resilient and functional in these respects is determined by the interplay of prior relationships, family stage and the impairments of bvFTD. Our findings demonstrate the importance of a whole-family approach in supporting families where a member is living with bvFTD.

Author contributions

JLF conceptualised, designed and recruited to the study, undertook data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafted the article and undertook revisions. ML and JRO provided critical overview and review of all aspects of the process and contributed to drafting and revising the article.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Florence Nightingale Foundation (JLF received funding for her PhD fees and associated research costs for three of six years). The Foundation played no part in the design, execution, analysis and interpretation of data, or writing of the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The study received approval from the National Health Service research ethics committee West Midlands–the Black Country (Rec reference number 11/WM/0326).