Status of Latin in the school

The school is a non-selective, all-girls state comprehensive school. There are currently 1,371 students on roll, 330 of whom are in the Sixth Form (ages 17–18). The Sixth Form is mixed. For GCSE (aged 15–16), the school follows the EduqasFootnote 1 examinations; at A Level (aged 17–18), it switches to OCR.Footnote 2 I was aware of some differences between the Eduqas and OCR GCSE specifications – such as the omission of some complex grammar and the lighter weighting of literature component in the Eduqas specification – and considered how this would impact on the transition to A Level, which presumes the OCR GCSE assessment.

The class chosen for my research

In order to research the issue of the transition from GCSE to A Level, I chose to work with Year 12 (age 17). There is one Year 12 Latin class in my PP2 school, comprised of 4 girls, all of whom were working at A* to A (the highest grades) in the subject. As well as looking at the data, from observing this group in their Latin literature classes, I quickly realised that they were all very competent in Latin. I did however notice a difference in their attitude to the prose literature (Cicero) compared to the verse (Catullus): they seemed to find Cicero's prose more challenging. One of my earliest observations of this class documents that the ‘idiomatic rendering of sentences – especially Cicero – is hard for students’.

Literature review

The OCR A Level specification

The Latin A Level developed by OCR currently consists of four elements: Unseen Translation (H443/01), Prose Composition or Comprehension (H443/02), Prose Set Text (H443/03) and a Verse Set Text (H443/04). Language and Literature components have equal weighting. I was teaching the Prose Set Text, Cicero's Pro Cluentio, for this research project, so below I have quoted elements of the specification I aimed to support.

The A Level enables learners to:

acquire the language skills which enable learners to read literary texts, both prose and verse, in the original language

acquire the literary skills which enable learners to read ancient literature, both prose and verse, in its original language with appropriate attention to literary techniques, styles and genres

apply analytical and evaluative skills at an appropriate level which show direct engagement with original texts in the ancient language (OCR, 2022, p. 2).

Here, there is a clear emphasis on students acquiring language and literary skills in order to read, analyse and evaluate set text literature in the original Latin. Literary analysis is supposed to follow general comprehension of the text. Despite this, the A Level assessments themselves do not engage much with the idea of developing reading proficiency; instead, the exam instructs students to analyse grammatical features and to translate a passage of unseen Latin prose and verse authors.

What motivates students to pursue a language?

Dörnyei (Reference Dornyei2005) asserts that motivation significantly affects language learning success. Motivation is ‘a dynamic, ever-changing process’ and ‘its research should also evolve over time’ (Dörnyei Reference Dornyei2005, 66). Dörnyei and Ushioda (Reference Dornyei and Ushioda2009) propose the ‘L2 Motivational Self System’, which is comprised of three componentsFootnote 3:

1) The Ideal L2 Self: the person who a learner wants to be, who speaks the L2. The learner is motivated by the idea of reducing the difference between themselves and the ideal self.

2) The Ought-to L2 Self: the ‘attributes’ the learner thinks they should have to reach their ideal self.

3) L2 Learning Experience: motivations related to the immediate learning environment and experience (e.g. the impact of the teacher, the curriculum, the peer group, the experience of success) (Dörnyei and Ushioda, Reference Dornyei and Ushioda2009, 29).

My project aimed to address the third aspect – the L2 Learning Experience. By facilitating efficient comprehension and analysis of original Latin, I hoped to give students a feeling of success when approaching Cicero's Pro Cluentio, which they perceived as a challenge.

Why should students be reading Latin, rather than translating it?

Language acquisition and fluency

As Krashen explains, ‘input must be comprehensible to have an effect on language acquisition and literacy development’ (Reference Krashen2011, 1). In order for students to acquire a language and be able to engage with it, therefore, they must be able to read and listen to it. In the case of Latin, which is not commonly spoken, reading is more relevant here. Krashen adds that input must also be ‘compelling’, that is, sufficiently interesting that the learner forgets the input is in another language (Krashen, Reference Krashen2011, 1). This would place the learner in a state of ‘flow’, where they are immersed in an activity, without any recognition of the time past (Csikszentmihalyi, Reference Hoyos1990, cited in Krashen, Reference Krashen2011). Krashen develops this further in his, Reference Krashen2017 article ‘The Case for Comprehensible Input’, where he compares comprehensible input with other methods of second language acquisition. He claims that comprehensible input is more successful in acquiring a second language than learning the grammar first, what Krashen calls the ‘Skill-Building’ method (Krashen, Reference Krashen2017, 1). I applied to this my project, which provided comprehensible input through embedded reading, rather than explicitly teaching grammar.

Assessment and fluency

The importance of developing fluency has also been recognised. Balme (Reference Balme1963) discusses teaching classical literature at the Sixth Form level, claiming that language should only be studied ‘as a means of understanding the thought, which, at first, will usually mean enjoying a narrative’ (Balme, Reference Balme1963, 102). Balme and Warman (Reference Balme and Warman1966) discuss their findings from the literary analysis exercises completed by students using Aestimanda (an anthology of Latin texts for developing the skills of critical analysis), concluding that their students ‘had their mind fixed on English translation rather than the Latin’ (p. 42) and that a passage needed to be grasped ‘at sense level’ (p. 46) or else literary criticism was futile. This suggests an emphasis on developing reading fluency when engaging with original literature, rather than translation.

More recent discussions of Latin literature focus on the challenge of specifically Virgilian Latin. Davies (Reference Davies2006) comments on the frustration of translating Virgil for students, who are deterred by the complexity of the grammar. This disadvantage can be applied to Cicero too. Butler (Reference Butler2011) discusses the teacher's perspective, noting that they feel the current situation ‘may seem impossible’ (p. 15) and it is common practice for them to give students translations (p. 16) rather than that they read the original. Like Davies (Reference Davies2006), Butler comments on how difficult it is for students to access Virgil: there are ideas that are ‘culturally unfamiliar’ and many ‘historical, mythological and literary allusions’ (Butler, Reference Butler2011, 15). Although it is true that cultural dissonance can create interest and ‘escapism’ for students as they connect with a world both like and unlike their own (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016, 125), it still requires a general understanding of the text, which complex grammar can obstruct. This sentiment was shared by the students I consulted for my project: the long passages, specialist terminology and complex plotlines of Cicero's text hindered their comprehension.

How should students be reading Latin?

According to Nuttall (Reference Nuttall2015), there are two different approaches to reading: top-down and bottom-up. A top-down approach involves the reader inferring meaning through the words, syntax and context of a passage; a bottom-up approach involves the reader in decoding a passage word by word. Macaro (Reference Macaro2003) recommends using both for effective comprehension. Reading coursebooks, used up until the GCSE exam, such as the Cambridge Latin Course textbooks, can often be used by teachers for top-down reading, with good teachers identifying opportunities for consolidating grammar; approaching original texts, as mentioned above by various commentators, can often compel students to take a bottom-up approach. Through my deconstruction activity, I intended to encourage students to conduct both kinds of reading approach.

The purpose of reading is also integral, not just the process. Nuttall (Reference Nuttall2005) outlines three types of reading:

1. Efferent: using the text to find out information students did not know before.

2. Aesthetic: looking for the literary features in a text.

3. Analytical: drawing out meaning through vocabulary and grammar (Nuttall, Reference Nuttall2005).

Hunt outlines that ‘teaching original Latin texts requires all three approaches’ (Hunt, Reference Hunt2022, 66). This can be challenging for both teachers and students. But embedded reading, I believe, can allow all three to develop organically and occur simultaneously.

Linear reading

Hoyos (Reference Hoyos1997) sets out ten rules for developing fluency in Latin. The key points are:

Latin should be read in the order it is written (from left to right). This includes subordinate clauses, which should be completed before the rest of the sentence continues.

Latin should be read many times and understood first, before it is translated.

The structure of the sentence – main clauses, subordinate clauses and phrases – should be registered before individual, unfamiliar words (Hoyos, Reference Hoyos1997, 3–4).

Hoyos explains that the long-term goal is for students to read and comprehend texts by a ‘holistic method’, as they do in English and modern foreign languages (Hoyos, Reference Hoyos1997, 5). By this method, they will gain a ‘sense’ of the sentence first, then the paragraph as a whole (Hoyos, Reference Hoyos1997, 5).

Since my research project aimed to adapt Cicero's text, notorious for the complexity of his syntactical and grammatical structures, I thought it fit to look at Hoyos’ chapters on word groups and word structures. Hoyos (Reference Hoyos1997) defines word groups as either a simple sentence, a subordinate clause or a phrase. For word groups, he adopts the term ‘sense-unit’, which neatly conveys the purpose of a word group: to add a layer of meaning to the rest of the sentence. To recognise a word group, Hoyos (Reference Hoyos1997) recommends looking for opening words, which function as signposts. Furthermore, word groups are short and begin and end with words linked in syntax and sense to them. I planned my deconstruction activity with this in mind, and in the later lessons I intended to share this method and terminology more explicitly with my students.

Linear reading in practice

Linear reading involves reading left to right, so that students perceive a sentence ‘not as a string of random words which must be reassembled’ but rather as ‘sentence units or partial sentences’ that ‘contribute to the overall meaning’ (Hunt, Reference Hunt2022, 87). Inspired by Hoyos (Reference Hoyos1997), Davies (Reference Hoyos2006) proposes linear reading in the classroom as a solution for improving the accessibility of Virgil's poetry. She claims that there are two consequences of the reading approach: ‘students learn to read Latin in sense units or word groups’ and contextual, morphological and syntactic expectations are created (Davies, Reference Davies2006, 174).

The former consequence allows the student to ‘experience’ the text and its poetic effects first-hand (Davies, Reference Davies2006, 174). Without the obstruction of a lack of comprehension, their sole focus can be aesthetic reading. Stronger points of analysis will emerge, founded on a solid comprehension of the text. The latter consequence will help students read any passage of Latin, as they will become more confident with the structure of Latin sentences and be able to predict the ideas or words that might occur. There is less frustration and thus, more success and motivation, involved in studying the literature. It is from the concept of linear reading, with this shared interest in motivating students, that embedded reading originated.

How can embedded reading motivate students, encouraging them to read, and therefore comprehend Latin?

The history of embedded reading

Embedded reading is a technique that was developed in 2012 by Clarcq and Whaley, primarily to help second language students improve their literacy. They appear to be responding to the issues I have raised about language learning motivation and comprehension.

Clarcq (Reference Clarcq2012) describes an embedded reading as three or more scaffolded versions of a text. It is designed to prepare students to comprehend text that the students perceive to be beyond their capability. She outlines two types of embedded reading: bottom-up and top-down. Bottom-up readings start with a simplified passage which provides the framework of an idea or story, and build up to the final, complex passage. Top-down readings are the reverse of this: they begin with the original text and gradually remove complexities with every scaffolded version. Clarcq (Reference Clarcq2012) warns that the ‘picture-in-the-mind’ created by the passage must be retained in every scaffolded version – this way, students are still able to understand the overall sense of a text.

Once students are able to comprehend the text, Clarcq (Reference Clarcq2012) suggests some follow-up activities for the next reading. This includes comparing or contrasting the base reading with the more detailed versions. It was this rationale that I applied to my research project: once students had completed the tiering process and better understood the meaning of Cicero's text, they could compare the original and the ‘base’ reading they created to conduct literary analysis. By ensuring students were reading the text, before analysing it, I was also fulfilling the requirements of the OCR examination specification.

Embedded reading in Classics: the method and benefits

Building on Clarcq's (Reference Clarcq2012) work, Sears and Ballestrini (Reference Sears and Ballestrini2019) argue that the ‘bottom-down’ approach to embedded reading – which they call ‘tiered reading’ – can support students’ reading proficiency of Latin, thus increasing their confidence with approaching original, complex Latin. Using the Daphne and Apollo story from Ovid's Metamorphoses, they outline a method for tiering texts. I have summarised it below:

Tier 3: Divide subordinate clauses into separate sentences. Supply necessary words (those that are repeated or omitted)

Tier 2: Replace constructions and add helpful, explanatory words such as names, conjunctions and pronouns.

Tier 1: Break up all or most compound sentences and simplify complex grammatical constructions. Remove modifiers and replace unknown vocab with high frequency synonyms (Sears and Ballestrini, Reference Sears and Ballestrini2019, 72–75).

Sears and Ballestrini (Reference Sears and Ballestrini2019) recognise similar advantages of tiering texts to Clarcq (Reference Clarcq2012): it fosters language acquisition as students become invested in the story and receive more comprehensible input; key vocabulary is repeated; and students can engage with the same text in many ways. They add that students feel less intimidated by longer passages of Latin; instead, they are comfortable with uncertainty, unfamiliar vocabulary and develop ‘a deep and enduring understanding’ of the texts they read (Sears and Ballestrini, Reference Sears and Ballestrini2019, 77). This additional effect, of improving students’ confidence and developing an appreciation for Latin literature, is what I wanted to impart.

Embedded reading in Classics: accessing A Level Latin literature

The final and most relevant research on embedded reading was conducted by Gall (Reference Gall2020) who used the approach to make Tacitus’ Annals more accessible and comprehensible for her Year 13 students (aged 18). Gall's focus was improving the comprehension of the text; she hoped that literary analysis would be a by-product of the activity. As Sears and Ballestrini (Reference Sears and Ballestrini2019) suggested, she tiered four prescribed chapters of the Annals, and in the span of a single lesson, allowed the students to experience the same text in ascending levels of complexity. Gall's (Reference Gall2020) results were encouraging and insightful. Her intervention clearly reduced the intimidation factor of the text, with one student appearing surprised at finishing a chapter. Furthermore, the embedded readings, being repetitious, cemented a strong memory of the narrative plot, such that students could focus on literary analysis when they reached the higher tiers.

Gall (Reference Gall2020) also usefully outlines some of the disadvantages to this approach, unlike earlier research which is generally more positive. She had ‘mixed’ results: students still required some guidance through teacher questioning to identify features, when comparing the original and simplified versions (Gall, Reference Gall2020, 17). Another disadvantage is the time taken by the teacher to produce embedded readings.

Having discussed ideas about language learning motivation, reading and the research into embedded readings, I shall now outline the research questions and teaching sequence that were inspired by them.

Research questions

RQ1: How do students say they usually approach Cicero's text?

RQ2: What do students report they are doing, both during and after, deconstructing Cicero's text?

RQ3: What did students say they value about the activity?

Teaching sequence

The activity I designed was an implicit form of embedded reading, a term I have invented which best describes it. Whilst Clarcq (Reference Clarcq2012), Sears and Ballestrini (Reference Sears and Ballestrini2019) and Gall (Reference Gall2020) created each tier, I gave the students an opportunity to do so themselves. Students were taught to deconstruct Cicero's work, which I promoted primarily as a tool for literary analysis. My objective was that it would also support students’ comprehension and fluency of the text.

Lesson 1: Introduction to the deconstruction of Cicero

In this lesson, as a group we translated part of Cicero's Pro Cluentio Chapter 5. Then I introduced the activity to them: deconstructing Cicero for the purpose of literary analysis, which I comically described as ‘Destroying Cicero’. I modelled the activity using a PowerPoint slideshow while students followed along in a work booklet which I produced.

The deconstruction process was broken down into steps resembling Sears and Ballestrini's example (2019): finding the subject, object verb, rearranging the sentence into standard Latin word order, then changing the metaphorical into the literal. Where there were subordinate clauses, students had to identify them, remove them and convert them into main clauses. The final step was to compare the deconstructed sentences with the original Cicero and comment on any striking features – on both a word and syntactical level – they consequently noticed.

At the end of the lesson, students were given a few minutes to jot down any thoughts about the activity, prompted by the open-ended question: what have you learned about Cicero's literary style or his work more generally from this exercise?

Lesson 2: A standard lesson

In this lesson, we looked at the final part of Cicero's Pro Cluentio Chapter 5 and followed the format of lessons that I have observed elsewhere in school. We started with translating the text, using the class’ preferred method of numbering the words in order, then we conducted literary analysis through ‘literary analysis bingo’. Students had to work in pairs to find literary features in the text and consider their effect in relation to the theme I had written on the board: Cicero's antagonisation of Oppianicus and Sassia.

Lesson 3: The second deconstruction

The lesson followed a similar format to the first lesson, but for a passage of Chapter 6 of the Pro Cluentio. Unfortunately, due to an unexpected bout of illness, I was unable to cover all the lines necessary for deconstruction in the lesson time. Nonetheless, I asked students to write down their thoughts on the activity. This time the question was modified: what have been the advantages/disadvantages of the deconstruction activity? Students were given some prompts:

Literary analysis

Understanding the plot

Being able to read the Latin

Lesson 4: The final deconstruction and consolidation

In this lesson, we finished off the deconstruction activity from the previous lesson. Unlike the first lesson, I gave students more independence and agency with the activity, prompting them to use their notes and discuss with their pairs, before asking me a question. As a final consolidation, students were asked to comment on the advantages and disadvantages again.

Methodology

The deconstruction process drew largely on the work of Gall (Reference Gall2020) who produced embedded readings for her Year 13 Latin class to make Tacitus’ Annals more accessible for them. My intention was similar – I too had recognised a lack of confidence when approaching Cicero; however, I took a different approach. As my class were high-achieving and secure in their Latin grammar, I thought I could develop Gall's work and teach them how to do the ‘tiering’ process themselves. My objective was that they would grow confident in comprehending and analysing Cicero's prose. By ‘destroying’ Cicero, students would appreciate the original. Furthermore, they would be working solely in Latin – hopefully this would allow them to start thinking in Latin and reading the text, rather than just seeing it as a strenuous exercise in translation.

As this group are evidently not representative of the population of Latin students across the country, I acknowledge that my findings are tentative and do not give a holistic understanding of the benefits of deconstruction in a Latin class with a more mixed-attaining group. Nonetheless, it could still be beneficial to discover how high-achieving students respond to this activity. The lesson sequence itself was quite disrupted. The first two lessons were conducted within four days of each other; due to a national strike, the final two were two weeks later. This may have affected the students’ memory of the process and purpose of the activity. Although this group was officially comprised of four students, for two of the lessons (lessons 2 and 3) a student who was repeating her exams joined the group. I have included some of her thoughts in my data; however, since she had an existing translation and past notes on literary analysis and context of the passage, it is possible that she used these to support her in the lesson, instead of just the activity.

Research methods

As the group of students I worked with were all of high-ability and the lessons for my teaching sequence were limited, I have collected qualitative data about whether my activity could foster a greater appreciation for Cicero's text, rather than trying to collect quantitative data for the impact on their academic achievement. I used various research methods: questionnaires, the observation notes of an additional teacher, my own observation notes, and the written work of the class. Since I have a variety of data, I believe I have a holistic understanding of the impact of my action research on this group.

To ensure that my research met the ethical guidelines for education research set out by the British Educational Research Association (BERA) in 2018, I obtained verbal consent from this class to use their written work and to participate in my research.

Findings

RQ1: How do students say they approach Cicero's prose?

Initial questionnaire: A Level Latin and Cicero's literature.

The questionnaire was broken down into two sections: one about A Level Latin generally and one more specifically about Cicero's literature.

The questions were as follows:

A Level Latin

1. Why did you choose A Level Latin?

2. How did you find the shift from GCSE to A Level Latin?

3. Did you experience any challenges when starting Year 12 Latin?

Tackling Cicero's literature

1. What steps do you take when translating a passage of Cicero?

2. Is there anything you find challenging about understanding Cicero's work? (You may want to consider: vocabulary, grammar, sentence structure, the historical context, literary analysis, understanding the plot, producing a readable translation)

3. How do you overcome these problems? (What do you do yourself? Is there anything your teacher does that helps?)

All students answered questions 4–6. Three out of four answered question 2, the other answered question 3; however, her answer can be used to inform question 2, as she discusses an experience of the transition. Below I shall briefly outline the results of the survey.

Initial survey: results

What challenges do students face when starting Year 12 Latin?

The responses for this question were as expected. All students commented on the greater complexity of the grammar and vocabulary at A Level, and two discussed how they were conducting more independent study to keep up with the pace of the class.

What steps do you take when translating a passage of Cicero?

All students mentioned how the teacher numbering words in the passage in an English word order helped them form a translation. Furthermore, three out of four students stated that they looked for the subject, main verb and paid attention to cases and verb tenses. Only one of the four students said that ‘thinking about the context’ helped her.

Is there anything you find challenging about understanding Cicero's work?

I provided prompts for the students. Three out of four students discussed the syntax in Cicero's literature – particularly comprehending lengthy sentences. One student noted: ‘While I have a literal translation, I don't understand the meaning behind it.’ This provides insight into how, from a student perspective, an English translation was not always conducive to understanding the meaning.

How do you overcome these problems?

There was a variety of responses. Three out of four students reiterated how numbering words helped them make sense of the Latin and two stressed how they benefitted from paired or whole class discussion of meaning. Overall, the responses to these questions confirmed my observations and my own experience of approaching Cicero: the step up to A Level was challenging for this group and uncovering the meaning of Cicero's work was difficult, on account of the complex grammar. I also gained an insight into the methods that had helped them with this challenge: numbering the text, identifying parts of a sentence, group discussion of meaning and the teacher's support.

RQ2: What do students say they are doing, both during and after, deconstructing Cicero's prose?

Since the deconstruction activity happened over three lessons, I shall try to discuss the data collected in the first lesson compared to the latter two, in the hopes that there will be a sense of progress or development as a result of the activity. As McNiff notes, when analysing data from action research ‘you expect to see improved learning’ (McNiff, Reference McNiff2014, 111). For my purposes, an ‘improvement’ is, primarily, seeing students develop confidence in comprehending and analysing Cicero's prose. Although subjective, this improvement was grounded in observation.

Students appeared to develop a sound comprehension of the text

When we began the deconstruction in the first lesson, some students needed frequent reminding of what the text meant. For example, I recall the word maerorem, as a new piece of vocabulary, causing some issues. However, by the time we finished the deconstruction, since the students had read the same idea in three different forms – ‘scaffolding provides opportunities for review and repetition’ (Clarcq, Reference Clarcq2012) – they were starting to consider the Latin without reference to the translation.

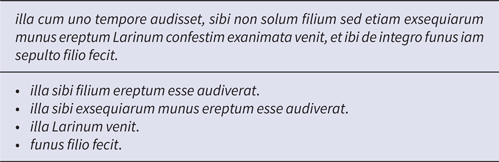

When we deconstructed the longer passage below – a main clause with an embedded subordinate clause – into three shorter sentences, some students seemed surprised at the result. It is possible that they recognised the simplicity of Cicero's work, and just how far he had embellished it for its rhetorical function.

Students are conducting some original, nuanced literary analysis

In the first lesson, when we rearranged the sentence below from Pro Cluentio Chapter 5 into the traditional ‘subject, object, verb’ order (Step 2), one student recognised that priusquam was ‘split up’.

The class teacher wrote in her observation notes that the class had not encountered tmesis before; yet, from her perspective, students were ‘looking at the word order [of the sentence] to see how tmesis coordinates the sentence’. This suggests that despite this technique being new to students, the deconstruction activity gave them an opportunity to try linear reading and consider the effect of Cicero splitting the word without prior knowledge. One student caught onto the effect almost immediately, commenting that it delayed the revelation of hominum rumor, creating a shock factor.

I believe the students were also conducting more literary analysis on a syntactical level. Compared to the students’ initial viewpoint of Cicero's sentence structures as ‘long and complicated’, by taking out subordinate clauses and converting them into main clauses they better understood how subordinate clauses function to add exaggerated or titillating detail so as to evoke the interest of the Roman audience. This was noted by the class teacher too, that students recognise Cicero ‘adding info to give shock/suspense in subordinate clauses’. Evidently, students were starting to develop an appreciation for the structure of Cicero's literature.

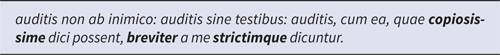

Likewise, in the third lesson, students noticed literary features that the class teacher claimed would otherwise go unrecognised. During the fourth lesson, when deconstructing the passage below, they identified the pleonasm breviter and strictimque and linked it to Cicero's authorial intention: to emphasise the succinct nature of his speech in comparison to the prosecutor of the previous trial.

Students are considering the generic function of the literature

By this, I refer to seeing the Latin as more than just a printed piece of text, by recognising it as a language with a purpose: communication. Although the students knew that Cicero wrote speeches for the court, I believe the activity encouraged them to adopt his persona, since students were constantly handling the Latin and making conscious choices to ‘destroy’ and modify parts of it. One student response in the questionnaire particularly echoed this sentiment: ‘I think it [deconstruction] is a good technique to demonstrate Cicero's method and thought process’.

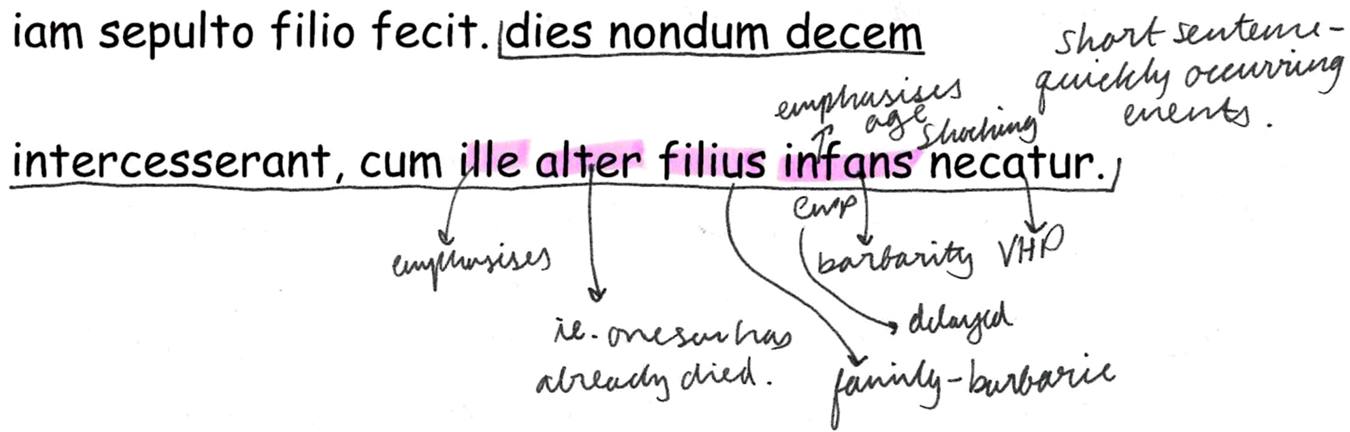

During the first lesson, we conducted literary analysis of the words in bold in the line below.

From examining the student's work (see Figure 1), I can see that she has considered not only the individual effect of each word, but also how the order of the words has made a difference to its delivery to Cicero's audience. She annotates the final word infans with the following comments: ‘delayed’, ‘EWP’ (emphatic word placement), ‘emphasises age’ and ‘barbarity’.

Figure 1. Student's annotation of Cicero text 1

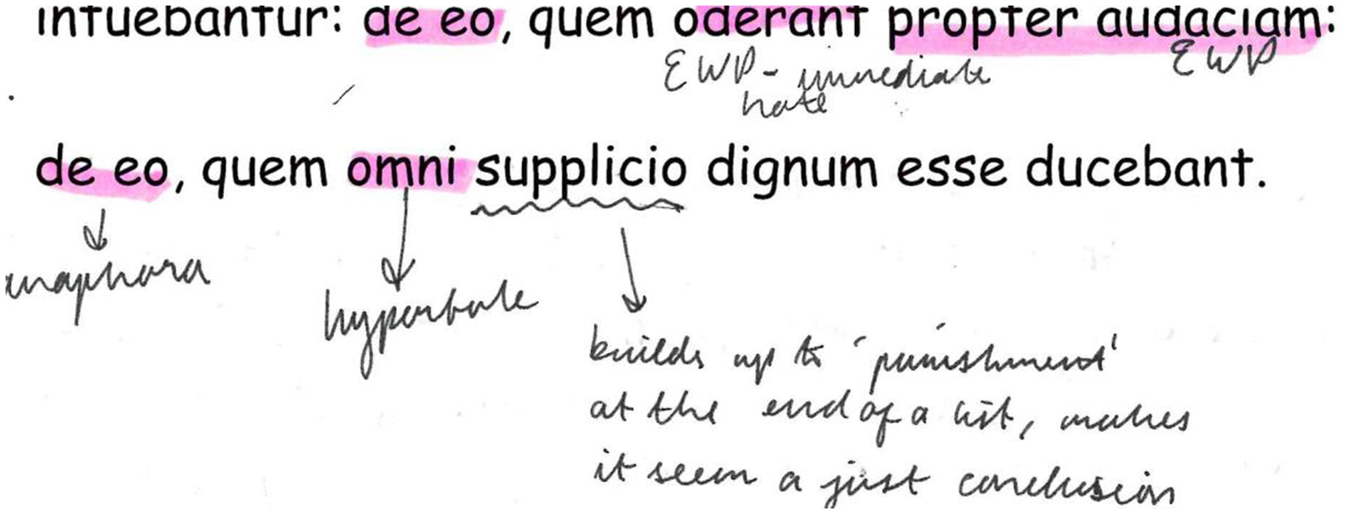

Likewise, in the fourth and final lesson, we were looking at a section of Pro Cluentio 6, which describes the case of Oppianicus the Elder. The passage featured a threefold anaphora of de eo, the last of which was in the following phrase:

de eo, quem omni supplicio dignum esse ducebant.

Here, the same student has annotated the noun supplicio with ‘builds up to ‘punishment’ at the end of a list, makes it seem like a just conclusion’ (see Figure 2). Again, it is evident that this student has considered the sequence of ideas in this passage, and the reference to ‘just conclusion’ possibly suggests a recognition of how this links to Cicero's generic intentions: to persuade.

Figure 2. Student's annotation of Cicero text 2.

Students are confident with the activity

From my own observations, the observations of the class teacher and the actions of the students themselves, the students grew more confident and efficient with the deconstruction activity. During the first lesson, there was some confusion over the grammatical terminology, such as the definitions of ‘subject’ and ‘object’ and the terminology ‘subordinate clause’ needed to be clarified. I anticipated the latter, giving examples to students in English as well as Latin, to support their understanding. By the third lesson, despite a large gap between the first deconstruction and this one, the students were deconstructing the text with less support from the teacher. The class teacher's notes corroborate this: ‘they seem to know the drill, starting to split up the clauses’. The students still required some scaffolding with subordinate clauses, so I prompted them by telling them to look for commas or the natural break of the ‘sense’ of the sentence.

By the final lesson, the students could recall the process without my prompting. This was primarily recorded by the class teacher: that one student ‘remembers step 1’ and that another ‘has accurately broken up the section into main clauses’. I noticed this when teaching the lesson too, since some students had finished a step sooner than I anticipated. I encouraged them to move onto the next, which they did with ease, referring to their notes from previous lessons. I also started to use Hoyos’ (Reference Hoyos1997) terminology by the fourth lesson, telling students to look for ‘signpost words’ to find the subordinate clauses. They responded to this terminology well; during the final deconstruction, they knew what I meant by a ‘signpost’ word.

RQ3: What did the students say they value about the activity?

The activity supported their comprehension

From my own observations, I think the deconstructed ‘base’ versions allowed students to gain a coherent and simple summary of Cicero's work. I noticed this particularly when teaching the second lesson of the teaching sequence, in which we conducted literary analysis traditionally, without the deconstruction. My own self-evaluation was that while students still came to sensible conclusions about the effect of stylistic devices in this lesson, there were more frequent questions about the meaning of the text. The deconstruction, it seems, gave students an opportunity not just to conduct literary analysis efficiently, but also to re-read the Latin and feel secure in its meaning. The student questionnaires after the third and fourth lessons support this. One student commented that ‘it has really helped me understand the plot. I didn't understand what Cicero was trying to say in fluent English at first’. Another student agreed, stating that ‘deconstructing helps to clarify the storyline’. A third response added that the process ‘simplifies the meaning, so it is a lot more basic to understand’. These comments suggest that the deconstruction activity could successfully replace the traditional translation-analysis sequence of a lesson, as it ensures both the sense and analysis of a passage is clarified together.

The activity gave them a better insight into the purpose of literary devices

As mentioned above, I think the activity extended the students’ understanding of literary devices. Whereas in the traditional lesson, they could identify features and tried to link the technique to the meaning of the sentence, in the deconstruction lessons, I think the two aspects came simultaneously: the students understood how meaning was created by the technique.

The activity was time-consuming

Three pieces of data confirm this aspect of the activity: my own self-evaluation and observation, the class teacher's observations and the students’ questionnaires. I think the first lesson was fairly efficient, and the Latin was simpler, so students could catch onto the steps and purpose of the activity better. The third lesson (the second deconstruction) was much slower, on account of more complex Latin and my emerging illness. Below is a section of the passage. Anticipating its difficulty due to the passive verbs, I modelled the deconstruction of this section with the students. Nonetheless, for them to grasp the conversion of passive verbs into the active required a great deal of abstract thinking. I was not entirely convinced they understood it, without looking at a translation.

Likewise, the fourth lesson, also affected by my poor health, was slow: as the class teacher noted, we did not start analysing Latin until 45 minutes into the lesson. All four students, in the questionnaires after the third and fourth lessons, commented on the length of the process, particularly compared with traditional lessons. They still stressed the benefit of the activity however, with two expressing the fact that it could be used for select passages: ‘perhaps not necessary for analysing every passage’. I would like to add to this that, much like Gall's (Reference Gall2020) own experience of producing embedded readings for her class, the preparation of the materials for the class, and considering how to scaffold the deconstruction, demanded more time than a typical lesson. I would agree with the students here, that it would be unfeasible for every lesson on the teacher's part too. I will go on to suggest in my conclusion, how the activity could be used in more efficient way.

Conclusion

Having presented and analysed my data, I will now arrive at some tentative conclusions about the research I have carried out. Firstly, the deconstruction activity improved the students’ comprehension of the text. By whittling down complex Ciceronian prose into more basic sentences, students provided themselves with useful plot summaries. The process of deconstruction, not just the final translation, contributed to their comprehension, as they were reading three variations of the same passage. As Clarcq (Reference Clarcq2012), Sears and Ballestrini (Reference Sears and Ballestrini2019) and Gall (Reference Gall2020) find, embedded readings provide repetition, so students grow a strong understanding of the sense of a passage.

Secondly, although some of the literary analysis could have been achieved without the deconstruction, students appeared to be conducting more nuanced and confident syntactical analysis. Gall too, noticed that ‘without prompting’ students were recognising and commenting on word placement (Gall, Reference Gall2020, 17). My research, I believe, has added another layer to this – the appreciation of Cicero's art as a writer. By taking an active role in the tiering process, students were able to gain a first-hand insight into authorial intent and take responsibility for the alteration of the text.

There were also some clear disadvantages to the activity, that could be modified in further studies. The time taken for the deconstruction was an issue, despite my efforts to streamline and scaffold the process with steps, lots of questioning and modelling. Although students worked more quickly in later lessons after some practice of the activity, they all recognised that the deconstruction took more time and effort than traditional methods of analysis. Additionally, on the part of the teacher, the activity took substantially more time to plan and create resources for than the traditional lesson I taught as part of this sequence. As Sears and Ballestrini (Reference Sears and Ballestrini2019) note, however, the resources could be used for beginners’ Latin, to introduce students to Cicero earlier in a course.

For future research, I would recommend promoting the activity as a method of achieving better comprehension, as this would allow for more precise data collection and foster more motivation. Next, I would discourage its use with highly complex passages of Latin, such as those with passive verbs, as the exercise can become longwinded and frustrating. Furthermore, there is the risk of losing the ‘picture-in-the-mind’ (Clarcq, Reference Clarcq2012) which an author is trying to create. To reword one of the student responses, I think the benefits of the deconstruction activity have to outweigh its disadvantages for a given passage. The deconstruction activity can be challenging; more successful outcomes will likely arise from selections with varied literary embellishments and that allow students to practise deconstructing a sentence structure several times. Overall, I do think that in addition to a feeling of satisfaction, language acquisition, reading and a genuine appreciation for stylistic choices can result from consciously ‘destroying’ an author's work.