Introduction

The role of political leadership in African politics is both central and problematic for Africanist scholars. Analyses of leadership first went out of vogue in the 1980s, when it became clear that differences between the most radical leftist leaders and the most avowed capitalist leaders were not that pronounced. By that time, almost all regimes in sub-Saharan Africa had developed autocratic one-party states (see Collier Reference Collier1982). However, in the 1990s, as it became evident that some leaders were more successfully implementing Structural Adjustment Programs and multi-party elections than others, studies of political leadership came back into prominence. Scholars began to re-examine how the dispositions of leaders and their political imperatives were driving divergent outcomes.Footnote 1

Though “bringing agency back in” has been an important shift, it has still been difficult to account for why some leaders are able to develop functional rule, while others are not. This is in part because the study of leadership too easily lends itself to a focus on the idiosyncrasies of particular leaders, making it difficult to divine systematic differences among neopatrimonial leaders. To overcome these problems, several scholars are now focusing on coalition politics. Studies have found that African leaders who develop broad-based elite coalitions are more likely to survive in office (Francois et al. 2015; Arriola 2009) and to promote economic development (Kelsall Reference Kelsall2011; Lindemann Reference Lindemann2011). Other studies find that presidents who secure the support of rural chiefs can bolster their legitimacy (Englebert Reference Englebert2000) and increase their likelihood of winning elections (Baldwin 2014; Koter Reference Koter2013).

This study seeks to bring the insights of these literatures together. A common thread connecting these discourses is the importance of rural policies to presidential success. The contention of this article is that rural constituents are critical not only to electoral politics and economic development but, first and foremost, to regime stability. Because of the inherent weakness of African institutions and the continued predominance of clientelism in politics, the manner in which regimes deal with rural elites and ethnic competitors has important implications for state stability. In turn, stable political conditions make it possible to institute economic and political reforms. Accordingly, this article makes the counter-intuitive claim that regimes that foster rural political support are more stable and successful than those that prioritize urban constituents, even in the absence of elections.

To illustrate the wide-ranging importance of the political incorporation of rural areas, this study examines the case of Ghana. In the 1970s, Ghana was plagued by coups and jeopardized by a severe economic crisis. Today, Ghana is regarded as one of the few successful democracies on the continent, with one of the most promising economies in sub-Saharan Africa. Ghana’s astounding transformation offers a critical study of how a weak state can be resuscitated. It can be argued that presidential leadership, and more specifically the strategic management of rural constituents, was central to this reversal.

This essay proceeds in three parts. Part I outlines why rural development is critical to regime stability and development. Part II presents evidence that the Ghanaian reversal was due to J.J. Rawlings’ strategic choice to prioritize rural areas. Finally, Part III makes the case for why structural analyses do not as effectively account for the outcomes in Ghana as these leadership choices do.

Rural vs. Urban Strategies

There has long been a consensus that rural constituents are critical to winning elections. Rural areas have historically been more populous in sub-Saharan Africa than the urban areas. At the same time, it has been recognized for decades that supporting farmers is critical to economic development.Footnote 2 But why would rural dwellers affect regime stability or have any impact on coup-politics?

Historically, scholars have argued that with the most important military garrisons and organized interest groups concentrated in the commercial capitals, African governments have perceived their primary threat to be destabilizing urban riots.Footnote 3 The strong correlation between urban protests and coups seems to support this perception (Gerling Reference Gerling2017). Indeed, since the “Arab Spring,” we have witnessed escalating riots in capital cities, which forced out longstanding autocrats in countries as diverse as Tunisia, Egypt, and Burkina Faso. The rural areas, on the other hand, appear to pose few political threats. This is particularly so in sub-Saharan Africa, which has only had a few short-lived peasant rebellions. In the absence of elections, therefore, the presumption has been that sub-Saharan regimes need not concern themselves much with their rural constituents. Henry Bienen and Jeffrey Herbst best encapsulate this thinking:

Successive nondemocratic African governments have also viewed the urban population as their main constituency because, although votes were not important, the fear of destabilizing urban riots was very real. Regimes that did not have to pay attention to rural voters did not favor agricultural interests and rural majorities. (1996:32)

In fact, pro-rural policies are important to stability for several reasons. First, supporting farmers can help sustain the economy and increase food security. Expanding rural road systems reduces the costs of getting food to market. Increasing farmers’ access to credit and inputs helps sustain both export and food crops. When farmers receive higher revenues, they can hire extra laborers, particularly from less productive regions. All of these factors help promote food security.Footnote 4 On the other hand, when farmers do not receive fair prices or adequate support, they can choose exit strategies, cutting out export crops to grow food crops, or selling products across the border on the black market. This can take a terrible toll on the economy. Madagascar in the 1980s provides a typical example:

[T]he government favoured the urban population by maintaining low prices for staple foods to the detriment of the rural producers…The reaction of the peasants was to concentrate on food crop production such as sweet potatoes and cassava, while reducing to a minimum unprofitable cash crops which the government wanted. Sometimes peasants retaliated by smuggling cash crops to neighbouring islands. For instance, almost seventy-five per cent of the 1982 peasant vanilla harvest was smuggled to the Comoro Islands. (Mukonoweshuro Reference Mukonoweshuro1990:383)

Advancing rural areas can also strengthen the central government against regional competitors. Generally, urban ethnic entrepreneurs mobilize populations to secure political followings. Promoting rural self-administration can diminish the power of these entrepreneurs, by fracturing political mobilization along local lines and diffusing other forms of political engagement. It thus provides a safety valve for regimes, without significantly limiting the power at the top. As Mahmood Mamdani argues, “localized reform in favour of the peasantry…consolidates the social base of the regime, and monopoly of power at the top neutralizes middle-class contenders for leadership from within civil society” (1996:214). This line of reasoning is, in fact, found repeatedly in Africanist scholarship. For example, Blessings Chinsinga observes of Malawi that, what “might look like decentralization from the centre may actually turn out to be a centralizing force” (2006:271). And, Jennifer Seely extrapolates from her study of Mali that, “Decentralisation preserves the top of the hierarchy, and prevents further undermining of the structure by a trouble-making or separatist group” (2001:505).

Because of these cumulative effects, sound rural policies may actually reduce the likelihood of military intervention. For one thing, declining living standards and military cut-backs disproportionately impact junior and middle-ranking officers who control battalions and are often coup-makers. Therefore, poor rural policies that result in food shortages and the contraction of export revenues can increase the likelihood of a subaltern coup.

Additionally, because sub-Saharan militaries are ethnically factionalized, they are easily politicized. Such politicization frequently occurs when a regime tries to protect itself from ethnic groups in the military—by denying promotions, initiating dismissals and arrests, and creating “ethnically-friendly” paramilitary forces (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985:467–69). Such actions triggered coups in Uganda in 1977 and 1985; Guinea-Bissau in 1980; CAR in 1966; Ghana in 1966 and 1972; Sierra Leone in 1967; and Liberia in 1980. If a regime supports rural areas and established rural elites, particularly in areas where the military is highly represented, it is less likely to fear ethnic groups in the military and strike out against members of the armed forces (Rabinowitz & Jargowsky Reference Price2017).

The 1980 coup in Guinea-Bissau illustrates how these factors can work in tandem:

[B]etween 1977 and 1979, when the impact of the Sahelian drought resulted in a severely depleted food-crop harvest and the Government was able to obtain internationally supplied rice, much of this was distributed within the urban sector rather than to the peasants who had until then been providing the Government with their surplus produce. With 80 per cent of the rice normally being grown by the Balanta, their discontent was directly transmitted to the soldiers, the vast majority of whom continued to retain direct ties with their rural homes, so that these economic and ethnic variables merged to further prepare the political stage for military intervention. (Forrest Reference Forrest1987:102)

For all these reasons, rural areas play a more potent political role than is generally assumed. Contrary to prevailing assumptions, therefore, urban bias may actually destabilize a regime. It is possible that the more dependent a regime is on its urban base, the more vulnerable it becomes to spiraling urban demands. Without a countervailing rural political base to anchor it, a regime can become “caught in an urban prison of instability and [function] at the whim of the city mob, the capital garrison, and the central university’s students” (Huntington Reference Huntington1968:209).

However, it might be objected that the term “rural” is too broad. It encompasses a wide range of social structures, economies, and geographies that incorporate an even wider swath of people of different classes, interests, and ideologies. Moreover, rural elites exercise different degrees of communal authority, legitimacy, and autonomy from that of the state. Regimes’ relationships with rural elites and rural areas reflect this diversity and complexity. States’ strategies and policies differ dramatically across regions. Almost all regimes develop positive relationships with some chiefs while suppressing others (Boone Reference Boone2003). Above all, the intricate nature of rural-urban networks renders the categories of “rural” and “urban” blurry at best.

These objections notwithstanding, the term “rural” is used here in juxtaposition to what has conventionally been understood by “urban” interests. Urban interests are generally defined as co-extensive with “civil society groups”—salaried workers, student unions, professional classes, civil servants, labor unions, churches, and unemployed youth. It has long been recognized that regimes implement pro-urban policies to appease these interests by creating jobs, augmenting wages and benefits, and keeping the price of food and imports low (Bates Reference Bates1981; Lipton Reference Lipton1977). In contrast, rural interests focus on the advancement of particular regions and the members of the ethnic groups most closely associated with those regions. Rural interests are shaped by the relative geographic concentration of natural resources and ethnic groups in Africa. Customary law also promotes the articulation of interests along ethno-regional lines, because resources are kept in the custody of the community and overseen by traditional elites. Therefore, as with urban interests, regimes can initiate policies that broadly support traditional elites and farmers to assuage rural interests.

Conventional wisdom holds that focusing on “civil society” or “urban” interests is necessary to sustain political order and consolidate power. This study argues the reverse is true. For a regime to survive and thrive it has to grow the economy, curb ethno-regional competitors, withstand incessant urban unrest, and prevent military politicization. These aims are best achieved by fostering rural support.

Case Study: Strategies and Outcomes

Research Design

To elucidate how a rural strategy relates to regime stability, this study presents an in-depth case study of J.J. Rawlings, the head of state in Ghana from 1981 to 1999. This case selection was made for two reasons. First, Ghana was able to stabilize and develop after being mired in extreme economic decline and a succession of five coups from 1966 to 1981. Ghana therefore represents a critical case of overcoming state decay and instability. At the same time, J.J. Rawlings presents a “deviant” case study. Deviant cases are those whose outcomes do not fit with prior theoretical expectations or wider empirical patterns. Deviant cases are central to theory building (Brady & Collier Reference Brady and Collier2004). J.J. Rawlings is a deviant case because he began with an urban political base but quickly forsook that base. He abandoned his military junta’s socialist agenda, which was supported by the junior officers and organized youth who had brought him to power. He even initiated politically poisonous policies, such as currency devaluation, wage cuts, and large-scale civil servant layoffs. By all rights his strategy should have failed, and he should have been ousted in a coup. Yet, Rawlings was quite successful. Therefore, examining why Rawlings prevailed despite crossing powerful urban interests can provide insight into how functional leadership and political reform can be attained in sub-Saharan Africa.

The following in-depth study uses process tracing to analyze Rawlings’ tactical decisions. It shows Rawlings’ success was due in large part to his ability to orient the state away from its long-standing urban bias to a rural emphasis. The case study traces how Rawlings strategically focused on rural development, and how that enabled him to stabilize the state, increase food production, extricate Ghana from her economic quagmire, and even survive multiple coup attempts.

J.J. Rawlings

J.J. Rawlings presided over a stable polity for two decades. What is more, he left power in 2000 after his party was openly defeated in the polls, setting the stage for Ghana’s future democratic success. One explanation for Rawlings’ success is that the timing of his accession to power was fortuitous. It came at the dawning of a new period, when international donors were taking a renewed interest in Africa. As a result, Rawlings was able to receive substantial economic support that allowed him to rebuild Ghana’s infrastructure and resuscitate her export trade. Moreover, his policy choices were dictated by the IMF and the World Bank and had little to do with Rawlings himself.

However, the outcomes were far less certain than these narratives might suggest. It was never a foregone conclusion that Rawlings would adopt reforms. The decision to introduce Structural Adjustment Programs alienated Rawlings’ urban political base, exposing Rawlings to political perils. Moreover, the junior officers and student organizers who brought Rawlings to power were almost entirely anti-imperialist, anti-IMF radical leftists. Crossing them could only be done at great personal risk. Instead, Rawlings’ success was due to his willingness to carry through the crucial resuscitation of the country’s failed productive base by cultivating rural support and sacrificing his political capital in the urban areas.

Birth of the Revolution

On December 31, 1981, J.J. Rawlings staged his second coup in as many years. Despite the fact that this time Rawlings had unseated a democratically elected government, his coup was widely popular. Rampant corruption and failed socialist policies had devastated the economy. The decay of the state was so great that the social fabric of Ghana had begun to unravel. “By 1975 corruption permeated every sphere of life and its prevalence had made bribery, embezzlement and larceny an everyday occurrence” (Chazan Reference Chazan1982:6). Rawlings had gained credibility initially in September 1979, when, only months after he had taken control of the state in his first coup, he ceded office to the democratically elected president, Hilla Limann. However, under Limann, few visible changes were made. Black marketeering flourished, commodities remained scarce, and infrastructure continued to deteriorate.

Upon assuming power for the second time, Rawlings announced he was launching a “Holy War” to cleanse Ghana of its ills. The new military junta, the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC), quickly implemented its revolutionary agenda: ending class privilege and bringing power to the people. Wealthy Ghanaians were targeted. Those accused of hoarding were publicly humiliated, stripped, and beaten. A “Citizens Vetting Committee” was created in February, with the power to investigate anyone for tax evasion. Hundreds of people were imprisoned and their property confiscated. Soon after, “People’s Tribunals” were established in each community. In the first year, hundreds of cases were brought before these tribunals and harsh sentences imposed. Even stealing was tried as a capital crime (Ray Reference Rawlings1986:103). The excesses of the revolution were so acute that the well-to-do went out in ragged clothing and poor sandals to avoid being targets of soldiers and youth rampaging through the streets.Footnote 5

To return power to the people, Rawlings called upon Ghanaians in his first national address to form “local [People’s and Worker’s] Defence Committees at all levels of our national life—in the towns, in the villages, in all our factories, offices and work places and in the barracks” (quoted in Oquaye Reference Ocran2004:97). The Defence Committees were instructed to undertake community development, protect workers’ rights, and end food shortages. The government press became filled with pictures of DCs cleaning up blocked sewage drains, repairing potholes, and establishing communal farms.

That such a radical regime would work with the IMF and implement liberal economic reforms was hard to imagine. Nonetheless, within a few months Rawlings recognized he would have to change tack and begin negotiations with International Funding Institutions (IFIs). But doing so presented very serious dangers to the Chairman of the PNDC (Herbst Reference Herbst1993).

In 1982, the organizational base of the new government was in the hands of the radical left, who were committed to breaking all “ties with imperialism, namely the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the governments and multinational companies of North America, Western Europe and Japan” and to “quickly build a Bolshevik-style revolutionary party” (Ray Reference Rawlings1986:41). Rawlings’ credentials as the leader of the “true Ghanaian revolution” were in part built on his criticism of former regimes’ complicity with the West. In several speeches in the first half of 1982, Rawlings attacked the Limann government for seeking foreign investment and promised he would “ensure that this exploitation should cease” (Yeebo Reference Widner1991:48). Moreover, Rawlings proclaimed that if he failed the revolution he would willingly face a firing squad. This was a powerful statement coming from the man who had ordered the execution of three former heads of state for forsaking the Ghanaian people, General Acheampong, General Afrifa, and General Akuffo.

What appears to have precipitated Rawlings’ volte face was his recognition of the enormous amount of capital investment needed to rebuild Ghana’s economy. Upon assuming power, the PNDC had quickly sent delegations to Libya, Cuba, and Eastern Bloc countries to negotiate for aid. But the aid offered was negligible. Bulgaria pledged USD300,000, Hungary 3,000,000 forints, and the German Democratic Republic 200,000 marks for the supply of drugs and hospital equipment (Ghanaian Times 1982a). Unlike the radicals in his cabinet, Rawlings lost confidence in the capacity of the socialist bloc to provide sufficient economic support (interview, J.S.L. Abbey, Accra, 2010).

In the spring of 1982, Rawlings appointed a National Economic Review Committee (NERC) to assess the economic situation. The Committee’s leading economic advisor, Dr. Joe S.L. Abbey, gathered evidence of Ghana’s dire straits. Abbey recommended opening negotiations with the World Bank. He reasoned that nothing the Western institutions could put on the table would be unacceptable, given the extreme situation the country faced. Moreover, his own assessment of what was required was not far removed from the orthodoxy propounded in Washington. In his estimation, addressing the entrenched problems in the Ghanaian economy would require the resuscitation of cocoa, adjustment of the cedi, and retrenchment of the public sector (interview, J.S.L. Abbey, Accra, 2010). Rawlings gave Abbey the green light to develop a proposal to be used as a basis for negotiating terms with donor institutions. Abbey drew up the “Economic Recovery Programme” (ERP), which he submitted to the IMF. Negotiations were begun in secret (Martin Reference Martin and Rothchild1991:239).

Not long after, the radicals began to make moves against the Chairman of the PNDC. On June 18 1982, the first abortive coup was launched against Rawlings. By August the PNDC Ruling Council, never a coherent body, was completely fractured. From October 1982 to January 1985, seven coup attempts were launched against Rawlings (Ray Reference Rawlings1986:106–11).

Yet, Rawlings prevailed. A number of critical choices allowed Rawlings to contain the military and stabilize the state. Rawlings’ capacity to consolidate political control and to ultimately implement economic and political reforms was related to his crucial decision to redirect the state’s energies towards the rural areas. This was achieved by channeling resources to rural and underprivileged areas, forging alliances with alienated segments of the population, including chiefs, and focusing attention on the underprivileged North.

Rawlings’ Rural Strategy

At the outset, the PNDC’s primary support base was urban leftists: student unions, labor unions, junior members of the military, and unemployed youth. In the heady days following the December coup, chiefs were vilified along with the wealthy elite. They were seen as a feudalistic relic to be overcome as part of the class struggle. Some were even publicly stripped and beaten for hoarding. But by 1983, Rawlings recognized that his economic and agricultural objectives could not be met without traditional support. As P.V. Obeng, former Co-coordinating Secretary of the PNDC, explains, we “started as very leftist, idealistic. We were very hot, and all institutions that were colonial and feudal and whatever were looked upon with suspicion. But then, when we started stabilizing we knew that we needed to get allies to partner with us in our programs.”Footnote 6

Rawlings indicated the PNDC’s new direction in national addresses. In his 1983 Independence Day speech, Rawlings invited “professionals, men and women of religion, chiefs, the lodges and everyone to break out of their insulating walls and shells and give the national effort a push” (Oquaye Reference Ocran2004:166; Yeebo Reference Yeebo1991:180). That August, Rawlings declared that, “Populist nonsense must give way to popular sense. Many of us have spent too much time worrying about who owns what, but there can be no ownership without production first” (quoted in Nugent Reference Nugent1995:113).

Speeches were accompanied by actions. In early 1984, the PNDC dissolved the PDCs/WDCs and replaced them with Committees for the Defence of the Revolution (CDRs). For the first time, membership in local Defence Committees, “was open to all persons or citizens of Ghana who were prepared to abide by and defend the basic objectives of the revolution” (Oquaye Reference Ocran2004:167). These changes were also reflected in Rawlings’ Cabinet. By the end of 1985, moderates had replaced the radicals. The radical trade unionist Amartey Kwei was replaced by the more moderate trade unionist, Ebo Tawiah. Non-commissioned officers and lower-ranking military members were no longer included in the PNDC.

Significantly, the first critical realignment came on the heels of the 1982 coup attempts. On December 28, Rawlings appointed the Nandom-Naa, one of the most important chiefs in the Upper Region, to his cabinet. Emmanuel Hansen observed, “A few months earlier, this appointment of what one would call a feudalist to such a high office would have been inconceivable…Ideologically it signaled the period of the renunciation of class war and the beginning of class peace, a theme which was to come up more frequently in the further pronouncements of Rawlings” (Hansen Reference Hansen1991:127).

Gaining the support of the Upper Regions was strategically imperative for another reason. The purges of the radical leftists had been perceived as ethnically motivated because the majority of those purged were from the Upper Region (National Reconcil[i]ation Commission 2004). To make matters worse, a significant portion of the armed forces hailed from that region as well. The political appointment of a respected traditional leader to a high political office was one way to “blunt the edge of any ethnic response which might arise as a result” of the expulsion, arrests, and executions of leading members of the radical leftists, many of whom “came from the Northern and Upper Regions” (Hansen Reference Hansen1991:127).

In addition to the Nandom-Naa’s cabinet appointment, Rawlings announced that he was creating two regions out of the Upper Region (Ghanaian Times 1982b). This was a long-held wish of the chiefs and people in the western part of the Upper Region, who had been forced to travel to Bolgatanga, over three hundred kilometers to the East, for most of their resources. Having a regional capital in the Upper West was a real coup for the area. In turn, winning over the traditional leaders who wielded enormous influence over their people was immensely important for the regime.

As expected, the promise of a separate region and appointment of the Nandom-Naa had an immediate effect. On December 30, the Nandom-Naa organized a durbar for the chiefs and people of Wa and Bozing “to express their gratitude to the government in its intention to create a separate region for the area” (Ghanaian Times 1982c). At the durbar, the Nandom-Naa “called on the people of the Upper West to justify the creation of the region by working harder than before…[and to] embrace the government agricultural program and intensify food production” (Ghanaian Times 1982c).

The PNDC also began to visibly support the Upper regions. The 1984 Independence Day celebration was launched with special prayers for the nation led by Muslim leaders around the country (People’s Daily Graphic 1984a). The same day, the PNDC immunized 3,200 people against yellow fever, in response to a discontinued anti-yellow fever program in the Upper West (People’s Daily Graphic 1984b). In subsequent years, Rawlings increasingly focused on the underprivileged North. In 1987, the “Food for Infants and Mothers program” was primarily channeled to the Northern Region. Rawlings also launched a “Non-Formal Education and Development Programme” “to reduce substantially adult illiteracy, especially in the Northern and Upper East and Upper West Regions, as well as other deprived and depressed local communities” (Rawlings 1990:106).

Critically, the PNDC committed itself to “supplying electricity to the northern parts of Ghana from the national transmission grid” as a way “to ensure regional balance” (Rawlings Reference Rabinowitz and Jargowsky1989:9). In his speeches, Rawlings emphasized the historic reversal his regime was making, explaining that “…since the 1960s the benefits of this great accomplishment have concentrated in the southern part of the nation, the PNDC’s [is determined] to extend…reliable electricity supplies to every part of this nation” (Rawlings Reference Rabinowitz and Jargowsky1989:48). Though progress was slower than promised, extensive work was begun on the electric grid in the Northern Regions in 1992.

The rhetorical shifts and new strategic alliances Rawlings made were part of a deliberate plan to move the country past the heightened tensions that dominated the second of half of 1982 so as to advance the PNDC’s new rural development agenda. During the period from 1984–88, the Rawlings regime began to “institutionalize its relationship with rural people” (Ninsin 1991:58). Rhetorically and symbolically, Rawlings intensified his support of the peasantry, while the urban populations were increasingly vilified.Footnote 7 The Ministry of Rural Development and Cooperatives put out a Rural Manifesto, which declared that, “As a group, the urban rich and poor have exploited the majority in the rural areas for a long time” (quoted in Nugent Reference Nugent1995:138). Rawlings’ rhetoric echoed these sentiments: “Our fellow citizens in the rural areas create the wealth to sustain the urban areas under conditions which increasingly threaten their own existence” (Rawlings 1990:41).

The Chairman of the PNDC also became more visible in the rural areas. “[D]uring the post 1985 period [Rawlings] developed a strong inclination to interact more with rural populations. In more dramatic instances he camped by villages, worked with them on community projects and held durbars with them” (Ninsin 1991:62). He furthered his alignment with traditional rural elites. Towards the close of the decade, “Rawlings and his entourage made a special point of attending chiefly durbars throughout the country. At these events, Rawlings identified publicly with the concerns of the chiefs” (Nugent Reference Nugent1995:205).

The PNDC was particularly focused on rejuvenating Ghana’s moribund cocoa industry. Because of the complete disrepair of the roads and railroads and the scarcity of trucks and auto-parts, when Rawlings came to power thousands of tons of cocoa were left to rot in silos and warehouses in the hinterland. The PNDC launched an all-out “cocoa evacuation” campaign to bring cocoa to the ports (Ghanaian Times 1982d). Universities and technical schools were closed for the semester and students were required to join the national Student Task Force, whose primary focus was carrying bags of cocoa to the harbor. In less than a month, the students carried fifty-three railway vanloads of cocoa to the Tema Harbor (Ghanaian Times 1982e). Many of the government’s early infrastructural projects were focused on road repair and the construction of storage silos in cocoa growing regions. By 1985, the PNDC had begun to restore the cocoa industry, in large part because the government continued to raise the price paid to cocoa farmers (Herbst Reference Herbst1993).

More broadly, the regime took concrete steps to further its rural development agenda. The allocation of government funds from 1983 to 1991 reflects the regime’s priorities (see Table 1). In 1983, nearly one-half of the expenditures went to agriculture. Thereafter, the allocation stayed fairly consistently at one-quarter. The rehabilitation of roads and ports consumed one-third of the first ERP budget and was almost half of the government’s expenditures from 1987 until 1991.

Table 1. Composition of Government Expenditure on Economic Services, 1985–1991 (Percentages)

Source: State of the Ghanaian Economy in 1992, Accra: The Institute of Statistical, Social and Economic Research (ISSER), University of Ghana, Legon, 1993.

A Programme to Mitigate Against the Social Costs of Structural Adjustment (PAMSCAD), begun in 1987, was initiated to redress “the deprivations endured by the productive rural majority” (Government of Ghana). PAMSCAD launched several rural poverty alleviation programs, including a program for the distribution of food to lactating mothers and infants, and a “Communities Initiative Programme” which funded community-organized development projects, such as building schools, digging wells, constructing latrines, and rehabilitating feeder roads.

Another initiative undertaken at this time was the introduction of a new local government system in 1988, the District Assembly (DA) system. The new system introduced two significant innovations. First, the District Assemblies were mandated to include chiefs. Assembly members were to be one-third popularly elected, one-third chiefs, and one-third government appointees. Just as importantly, funds were ceded directly to the Assemblies from the central government. A District Assembly Community Fund (DACF) was created to which the government was mandated to dispense at least 5 percent of its expenditure annually.

In the end, plagued by dysfunctions, corruption, and inefficiencies, the District Assemblies proved far less successful at local development than the reformers had hoped. Politically, however, the new local government apparatus helped solidify rural support. It provided a means for the PNDC to forge alliances “with the most influential powerbrokers at the community level” (Nugent Reference Nugent1995:205). The local elections also gave the regime “a new capacity to tap and mobilize rural support” (Kraus Reference Kraus and Rothchild1991:149).

This was made manifest in the high levels of rural participation in local DA elections in 1988–89. Rural areas averaged over 60 percent turnout. In contrast, urban turnout averaged 44 percent. As Naomi Chazan observes, “For the first time in postcolonial Ghanaian history, a regime derived its support primarily from rural constituencies” (1991:36–37). Of course, Rawlings did not win over all rural areas. In some races, high turnout was due to the opposition’s ability to “get out the vote” in the hopes of undermining the power of the PNDC locally (Herbst Reference Herbst1993:89). Ashanti and the Eastern Regions remained hostile to the PNDC, despite the fact that cocoa growers from those regions were beneficiaries of PNDC policies. This is not surprising, given these two regions had historically been closely linked to conservative political parties. Moreover, many wealthy cocoa farmers and chiefs who suffered extreme indignities during the early days of the revolution never overcame their antipathy for the regime.Footnote 8

Yet, overall, in the 1980s the Rawlings’ regime made a concerted effort to address long-standing regional inequities, woo traditional leaders, build transportation infrastructure, and resuscitate agricultural productivity throughout the territory. As a result, Rawlings was able to build grassroots support in the countryside, particularly in the formerly neglected northern areas, the Volta Region, several of the cocoa areas in Northern Brong Ahafo, and in the Western Region. With its rural development initiatives, the PNDC began to increase food production and stabilize the economy. This, in turn, enabled Rawlings to solidify his power and prevent the military from splintering against him.

Urban Discontent

While Rawlings was building a faithful rural following, his allure in the urban areas was wearing thin. As the PNDC increased allocations for rural development, it ended popular subsidies on goods and services consumed primarily in urban areas. By the end of the 1980s, only a handful of price controls were still in place (Herbst Reference Herbst1993:62–63). The government also undertook a serious “retrenchment and redeployment” program of skilled and semi-skilled urban workers. By December 1992, 60,937 employees had been cut, among them messengers, typists, clerks, charwomen, watchmen, cleaners, artisans, and drivers.

Normally perceived as the “third-rail” in African politics, the PNDC was willing to weather the inevitable storm that this rise in urban living costs would engender. And weather it they did. Throughout the 1980s, the PNDC was confronted with a series of workers’ strikes and student demonstrations. Between “1985 and 1988 the government had to contend with demands from almost all the key political groups in the country, including labor and students, manufacturers and professional politicians” (Ninsin 1991:56–57).

Although the government gave occasional concessions to students and unionists, for the most part it cracked down on them. After 1985, the government “relentlessly ferreted out and detained or intimidated critics and organized opposition” (Ninsin 1991:55). In response to a series of strikes and student protests in June 1987, the government closed down all three universities in Accra and dismissed and arrested prominent student leaders (Nugent Reference Nugent1995:179). Some workers’ groups were denied the right to organize. Others were “systematically depleted through retrenchment [and] privatization of state enterprises” (Ninsin 1991:56). The PNDC also cracked down on Union leaders. The General-Secretary of the TUC, L.G.K. Ocloo was hounded by security forces and threatened with trumped-up corruption charges. Eventually, Ocloo went into exile and was replaced by the more tractable A.K. Yankey, who defended the government’s unpopular minimum wage legislation (Nugent Reference Nugent1995:181–82).

In short, by 1987 the government had lost “decisive support among urban-based classes” (Ninsin 1991:57). On the whole, Rawlings’ political and economic strategies of the 1980s were geared away from the urban areas and towards rural constituents. Although urban strikes and demonstrations spiked during this period, the regime’s stability was never seriously threatened. Continued coup attempts were put down relatively quickly.

Effects of Rawlings’ Rural Strategy

By 1990, Ghana’s long-standing urban bias had been reversed. A World Bank study found “significant reverse migration is occurring from non-agricultural to agricultural occupations since the introduction of Ghana’s reform program” (Jaeger Reference Jaeger1991:vi). Chazan sums up the transformation:

[T]he more notable outcome of the structural Adjustment Program [was] the reversal of the terms of trade between the rural and urban areas. Hikes in producer prices and infrastructural rehabilitation meant that the lot of many rural communities improved, while residents of the cities carried the burden of the reform program. (Chazan Reference Chazan and Rothchild1991:34)

Nonetheless, it is difficult to gauge how much of these improvements actually reached the rural majority. Herbst found in 1993 that, “people in the rural areas are still absolutely poorer than they were in the mid-1970s” (Herbst Reference Herbst1993:83). Several scholars at the time also emphasized that in the cocoa growing regions, only a small number of wealthy farmers had, as yet, seen any kind of financial gain (in part because cocoa trees require several years to mature and bear fruit).Footnote 9 Others found that the reintroduction of school fees and decentralization measures shifted a considerable tax burden onto the rural areas (Kraus Reference Kraus and Rothchild1991; Ninsin 1991). And although the PNDC forged alliances with traditional elites, several important chiefs were removed by the PNDC.Footnote 10

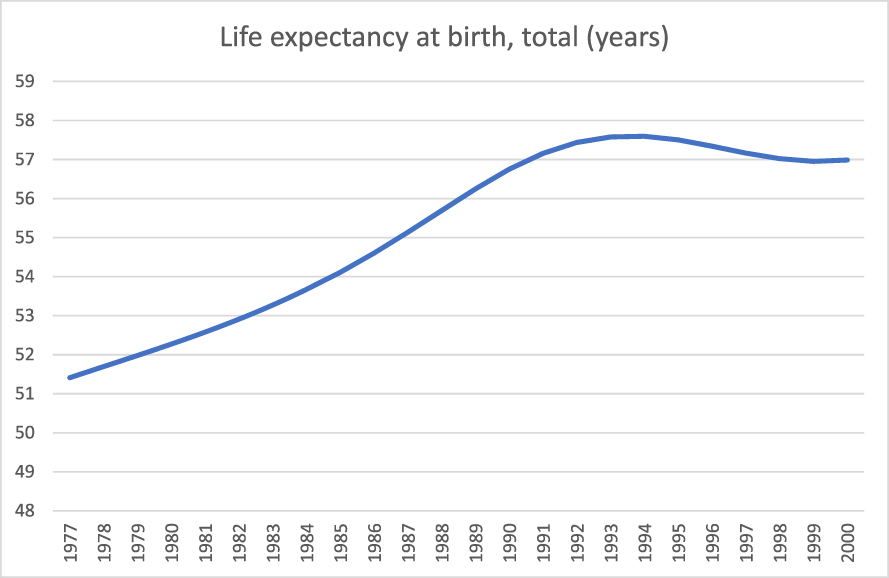

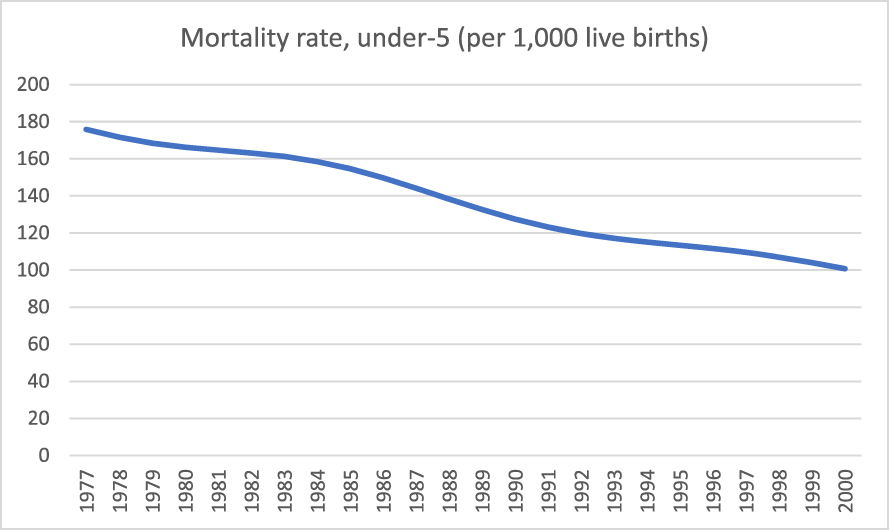

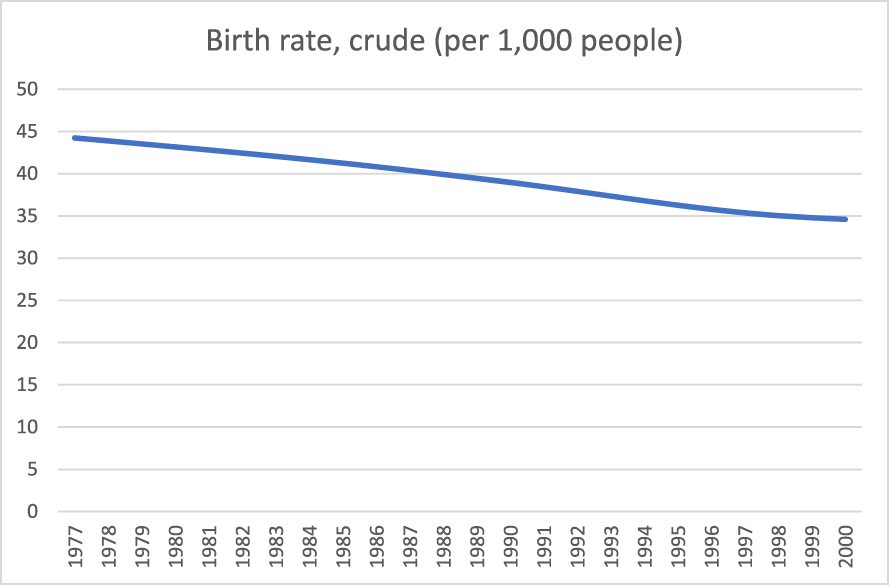

Yet, major indicators support the observation that “the change in economic conditions since the extraordinary depressed years of 1982–1983 is palpable to anyone who has been in Ghana” (Kraus Reference Kraus and Rothchild1991:129). From 1977 to 2000, life expectancy increased from an average of 51 years of age to 57, while infant mortality and birth rates decreased (see Figures 1-4).

Figure 1. Life Expectancy at Birth (both sexes), Ghana 1977–2000

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank Databank, Accessed August 2017

Figure 2. Infant Mortality Rate (both sexes), Ghana 1977–2000

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank Databank, Accessed August 2017

Figure 3. Birth Rate (both sexes), Ghana 1977–1995

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank Databank, Accessed August 2017

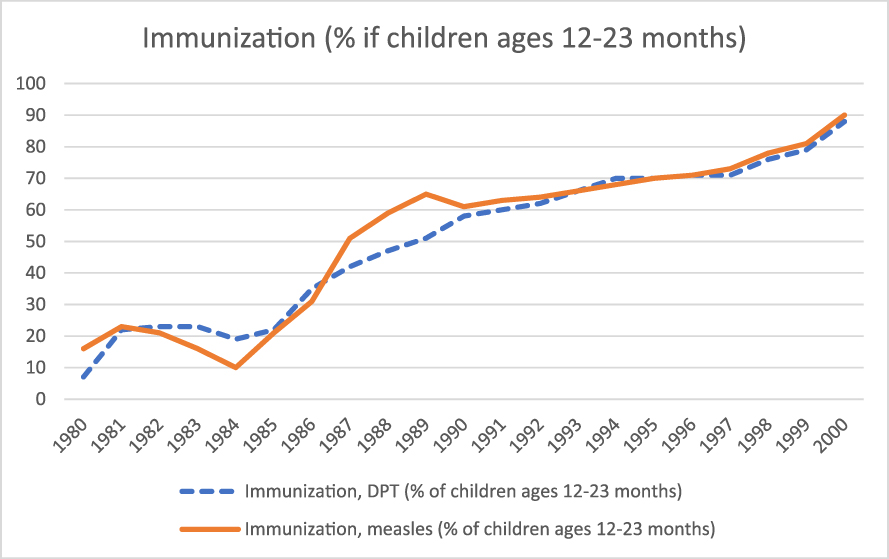

Figure 4. Immunization of DPT & Measles, Ghana 1980–1995

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank Databank, Accessed August 2017

Perhaps the most important gains cannot be gauged by econometric figures. As Paul Nugent argues, “It is hard to exaggerate the political impact [of new roads] in areas where poor roads had long been a source of grievance” (1995:206). And it was not just roads. The PNDC had for the first time started to provide underserved rural areas with pipe-borne water, schools, immunization campaigns, and later, electricity. The introduction of television and radio to rural areas helped people in isolated villages feel a part of the national community. The open encouragement of cocoa and food farmers also induced many farmers to support PNDC policies.

The greatest indicator of the positive impact of Rawlings’ rural policies is manifest in his electoral successes after introducing multi-party elections in 1992. In the 1996 elections, the party Rawlings established, the National Democratic Congress (NDC), “swept the board” in the rural areas, outside Ashanti and the Eastern Region (Nugent Reference Ninsin and Rothchild1999:307). Even after Rawlings’ departure, the NDC continued to carry the vote in the formerly neglected areas he had focused on in the 2004, 2008, and 2012 elections (the Volta, the new cocoa-growing areas of the Western Region, such as Sefwi-Aowin and parts of Brong-Ahafo, as well as the Upper East, Upper West, and Northern Brong-Ahafo).Footnote 11

While the benefits to the rural areas have been debated, the same is not true of the urban areas. There seems little question that organized urban groups fared worse under the PNDC. And yet, despite plummeting urban support, the regime was able to stay in power, stabilize the polity, and develop the economy. Rawlings’ success in reversing Ghana’s long-standing urban bias in government policy—by supporting local traditional elites, offering favorable terms to producers and incentives for rural re-settlement, decentralizing government, and expanding rural infrastructure—were the keys to his achievements.

In summary, centering on the rural areas and the neglected North enabled Rawlings to bring the rural chiefs and their followers on board. Initially, this was critical to making sure that the Northern constituencies, particularly those in the security forces, did not turn against the PNDC after the “revolutionary” leftist faction had been purged. Concentrating on rural areas and traditional leaders also enabled Rawlings to resuscitate the export economy and increase food production. These combined policies allowed Rawlings to achieve political consolidation during his most precarious period and prevent a military intervention.

In its first decade, the Rawlings regime had done what is conventionally thought not to be possible for African governments: it had developed a rural base of support and spurned its urban constituents, all in the absence of multiparty elections. Though there were some bumpy moments, the regime was never really put in jeopardy. The realignments begun in 1982 and continued through the 1990s enabled the government to sustain political stability and reverse years of economic degradation.

Structure not strategy?

Placing so much emphasis on leadership may be objected to, particularly when so many structural/institutional arguments can be used to explain Rawlings’ success. Certainly, structural and institutional factors contributed to Ghana’s fate. For one thing, Ghana received monetary support from the international community for implementing structural adjustment programs (SAPs). Furthermore, when Rawlings took over, political opposition was very weak, and the economy was in shambles (Chazan Reference Chazan1983). Implementing structural adjustment programs, therefore, was potentially not as difficult or risky as in other states. According to Kwabena Asomanin Anaman, “an important contributing factor to the general population’s receptivity to a major structural adjustment programme [in Ghana] was the unavailability and high cost of food” (2006:12,15).

Yet, there were equally significant structural factors that might have harmed Rawlings. Historically, it has been hard for military regimes to sustain state control (First Reference First1970:437–38). In 1982, it was far from evident that Rawlings would be able to maintain power. “Unless the military government is able to muster the resources of the country for the improvement of the economy and take positive measures to get on to its own feet in the first instance, which is impossible with most African countries, it soon finds itself in rather difficult economic straits” (Ocran Reference Nugent1977:93). This had happened before in Ghana, and the conditions were in place that made it a likely scenario again.

When Rawlings assumed power, Ghana was in an economic crisis: exports had halved, the population was suffering from extreme food shortages, schools had few books or basic writing supplies, hospitals lacked essential provisions such as bandages, anesthetics, and basic medicines, and the transportation system “once the pride of Ghana, was literally in ruins” with decrepit railroads and tarmac giving way to bush (Price 1984:165). That Rawlings’ revolutionary government was “actively persecuting professionals, calling them ‘parasites’ and ‘counter-revolutionaries,’” only exacerbated the situation by creating an exodus of skilled personnel (Howard Reference Howard1983:486). At the same time, the revolution had unleashed young militants who were pursuing personal vendettas in the name of revolutionary righteousness. Within the first eighteen months, revolutionary retribution had begun to undermine popular support of the government throughout the country (Howard Reference Howard1983:474).

The situation turned dire in 1983. While the country was facing its most critical drought and famine was beginning to plague the countryside, approximately 1.2 million Ghanaians were expelled from Nigeria. “[R]eturning Ghanaians were faced with massive food and goods shortages, a crippled transport system and an economic infrastructure in a state of total disrepair” (Brydon Reference Brydon1985:585). One witness to the situation described how the initial jubilation over the revolution turned to disillusionment: “The common slogan of the general public after 1983, the year of the most severe drought in the country’s history, could be summed up with a common saying of the Akan people of Ghana, obiara ba, saa na obeye, meaning that ‘whoever comes to power, will do the same’” (Anaman 2006:11). All in all, the odds of success were decidedly not in Rawlings’ favor. The tide could easily have turned against him.

It is true that Rawlings had over a decade to consolidate his regime before he had to introduce elections. Though this undoubtedly enabled Rawlings to consolidate control, it cannot be considered singly decisive. Were that so, there should have been fewer coups prior to 1990. As we know, an inordinate number of authoritarian and military regimes experienced coups prior to the period of democratization (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith2001).

The most compelling structural argument is that international forces were at play. For example, it is argued that Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, was undermined by western powers, whereas Rawlings was supported by the west. Indeed, Nkrumah’s anti-imperialist rhetoric, his relations with Eastern-bloc countries, and his support for anti-colonial struggles made him easy fodder for Cold-War fear-mongers. He was denied crucial financing, and there is clear evidence that the CIA supported anti-Nkrumah plots throughout the 1960s in addition to being in contact with the 1966 coup leaders.Footnote 12

Nonetheless, Rawlings’ situation in the early 1980s was not so dissimilar from Nkrumah’s. Rawlings’ relations with Libya and Cuba had put him in the cross-hairs of the Reagan administration. At the time, his government alleged numerous CIA plots were carried out against it. The PNDC believed that the sudden expulsion of 1.2 million Ghanaians in 1983 was instigated by the Nigerian government at the behest of the United States in the hopes of destabilizing the regime (interview, P.V. Obeng, Accra, October 2010).Footnote 13 Two years later, a number of CIA agents were arrested in Accra, among them a former commander of the most important military barracks in Accra, who was in command from 1982–83, when several coup attempts were launched against Rawlings.

Again, in 1986, eight U.S. mercenaries were seized off the coast of Brazil with six tons of weaponry. The mercenaries reportedly claimed they were headed for Ghana to join a coup funded by a Ghanaian dissident with CIA ties.Footnote 14 The CIA even conducted a “spy swap” with Ghana in 1985. Rawlings’ cousin, Michael A. Soussoudis, was tried and sentenced to twenty years in prison on two counts of espionage. Within days of his sentencing, Soussoudis was turned over to the Ghanaian Ambassador on condition that he promptly leave the country.Footnote 15 In exchange, eight Ghanaians, described by U.S. officials as “of interest to the United States” along with their families, were flown to an unidentified African country (Hager & Ostrow 1985).

To protect himself from these various conspiracies, Rawlings built a formidable security apparatus (with Cuban and Libyan support, not Western aid). But so had Nkrumah, who had surveillance officers and troops who were armed and trained by the Soviets and Chinese (Baynham Reference Baynham1988). Given all these similarities, it is quite plausible that, without the loyalty of his own armed forces, Rawlings might have succumbed to a (CIA-backed?) coup, as Nkrumah had before him.

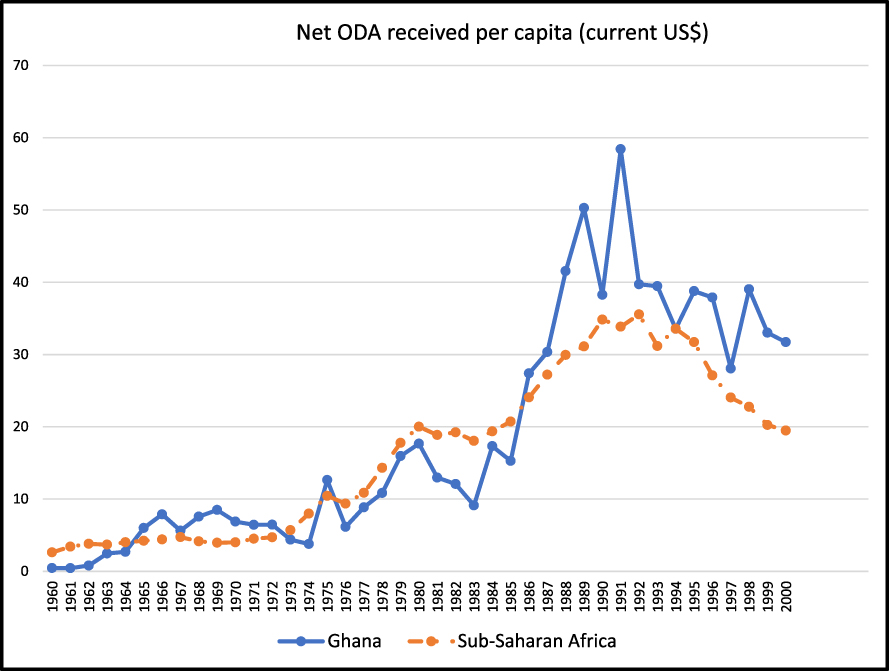

Furthermore, although International Financial Institutions (IFIs) eventually financed Rawlings, they were cautious at first. The PNDC government did not receive substantial aid before 1986 (see Figure 5), and the aid received was “substantially below” the average aid-per-person given to other African countries (Herbst Reference Herbst1993:132). As late as August 1986, the Reagan administration, angered by Ghana’s rhetoric and “Castro-style foreign policy,” threatened to cut off all its aid. Therefore, there seems little evidence to support the idea that Rawlings was kept in power by Western aid; rather, what was critical was Rawlings’ tactical use of that aid.

Figure 5. Per Capita Overseas Development Aid Compared, 1960–2000

Source: World Bank databank | World Development Indicators

To explain Rawlings’ success either in terms of funding or timing is simply insufficient. Though confronting the same structural problems Rawlings faced, his conservative predecessor Hilla Limann had been reluctant to adopt IMF reforms. Limann’s fear of the potentially destabilizing effects of devaluation kept him from reaching any agreement with the Fund, despite continual pressure from the IMF and World Bank (Committee on Foreign Relations 1982). And Limann did not have radical revolutionaries in his cabinet to whom he was indebted!

Neither the plans for decentralization, retrenchment of the civil service, nor the focus on export agriculture had come wholly from the IMF. These initiatives emerged, in large part, out of the PNDCs commitment to end corruption by decentralizing government, its conviction that independence rested first and foremost on food self-sufficiency, and its recognition of the need to rehabilitate the productive base of the economy. Even conceding that Rawlings was left with few choices, the extent to which Rawlings was able to restructure the economy and restore stability to the state has to be understood as primarily due to the regime’s willingness to undertake such measures in the first place.

Nor can Rawlings be understood to have implemented rurally-oriented policies solely as an attempt to build up rural electoral support. Rawlings did step up infrastructural projects in the run-up to the elections in 1992, in part to buy rural votes (Oelbaum 2002). But the infrastructural projects that were undertaken had been planned long before and were consistent with the regime’s initial policy objectives. Moreover, the push for elections forced the regime to make greater concessions to urban voters. In 1992, the PNDC partially capitulated to demands for increased wages because it feared anti-regime demonstrations might force the government to suspend elections, which would have had grave implications for continued donor support (interview, J. S. L. Abbey, Accra, September 2010). After 1992, the government’s relations with business also substantively improved (Oelbaum 2002:307).

In conclusion, nothing was pre-ordained. There were pre-existing conditions that could have supported either failure or success. In fact, contemporary commentators anticipated the opposite outcome. Robert Price described Ghana as being in a crisis “so severe that it might accurately be termed a crisis of economic, if not political, survival” (1984:165). Chazan held that, “The second populist experiment in Ghanaian politics merely reaffirms, at this juncture, the fragility of state power and the limitations placed on its wielders in the midst of the breakdown of the state” (1983:483). Richard Jeffries projected that the Rawlings government would “muddle through,” implementing “minor’ and “ineffective” economic policies that would be “the politically most safe course of action” but would “almost certainly also result in the further disintegration of Ghana as an effective nation-state” (1982:317).

That reality so dramatically diverged from what contemporary scholars took to be fairly certain ends, at the very least, suggests that circumstances did not entirely dictate what came to pass. It was clear that Ghana had nowhere to go but up and that Rawlings was left with few choices but to work with the IMF. But it was far from conceivable in the 1980s that Ghana would become one of the highest-growing economies on the continent and eventually the paragon of democratic governance. The level of success achieved, therefore, is best ascribed to Rawlings’ political stewardship.

In the end, J.J. Rawlings successfully presided over a stable polity for two decades. He took over a state that had all but collapsed and left one in its stead with real institutions and political stability. Overall, Rawlings’ success has to be understood as due to his leadership and more specifically to his willingness to carry through the crucial resuscitation of his country’s failed productive base by sacrificing his political capital in the urban areas.

Conclusion

This article makes the case that leadership is decisive to political outcomes. Without a doubt, institutions and inherited circumstances structure the scope of possible actions political actors can undertake. Several factors may influence a head of state’s policies, such as the country’s resource endowments, the regime’s relationship with external powers, or whether the regime is opposed by a large centralized kingdom, to name a few. Nonetheless, within these constraints there is a wider range of tactical possibilities open to leaders than is often recognized in the scholarship. Indeed, “character matters in the way leaders incorporate the features of the political landscape social scientists so often take as given into their decision making” (Widner Reference Van de Walle1994:152). How leaders respond to their inherited circumstances has enormous political implications, particularly in weakly institutionalized states, where the whims of the head of state can have far-reaching ramifications.

At the same time, African leaders do not function in a vacuum. Just as it has been argued that the alliance of classes of actors was critical to political outcomes in early modern Europe, in contemporary Africa, the continuing transformation of predominantly agrarian societies has empowered particular classes above others in shaping the political landscape. The relative geographic concentration of ethnic groups as well as the persistence of traditional networks tying urban communities to rural ones have kept ethnic mobilization a central form of politicization. Coupled with this, the insecurities of the African state make the capacity to forge strategic alliances with strong opposition leaders critical to political success or failure.

The upshot is that the manner in which rural populations and chiefs are incorporated into the state is vital to political outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa. By coopting rural elites, supporting agriculture, and focusing on rural development, a regime can better avert economic decline, minimize ethnic mobilization, and suppress military politicization. The influence of chiefs in societies may be lessening as urbanization and literacy increase; nonetheless, chieftaincy and regional populations remain crucial components of stability and regime success in Africa for the foreseeable future.

Acknowledgments

I have received support and valuable feedback from several quarters, but, above all, I would like to thank Catherine Boone for her guidance, support, and encouragement.