Introduction

Schizophrenia is a chronic mental illness with a significant impact on patients’ lives. It is associated with substantial psychosocial disability, high rates of comorbid psychiatric conditions, a greater need for mental healthcare services, and high risk of suicide.Reference Owen, Sawa and Mortensen 1 , Reference Lehman, Lieberman and Dixon 2 Patients with schizophrenia are also at an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.Reference De Hert, Detraux, van Winkel, Yu and Correll 3 , Reference Laursen, Munk-Olsen and Gasse 4 Current treatment guidelines recommend antipsychotic medication as first-line treatment for a patient experiencing an acute exacerbation of symptoms.Reference Buchanan, Kreyenbuhl and Kelly 5 , Reference Hasan, Falkai and Wobrock 6 Once stabilization has been achieved, continuous lifelong antipsychotic therapy is recommended to maintain symptom relief and reduce the risk of future relapse.Reference Buchanan, Kreyenbuhl and Kelly 5 , Reference Hasan, Falkai and Wobrock 6 Given the complexity and heterogeneity of schizophrenia, there is no single treatment that will work for every patient over the entire course of illness. Patients and clinicians need more treatment options to effectively manage symptoms while limiting side effects.

A combination of the antipsychotic olanzapine and the opioid receptor antagonist samidorphan (OLZ/SAM) is in development for the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. Among the existing antipsychotics, olanzapine is known to be effective in the treatment of schizophrenia, with efficacy in short-term stabilization of acute episodes as well as long-term maintenance therapy.Reference Kahn, Fleischhacker and Boter 7 , Reference Lieberman, Stroup and McEvoy 8 In studies comparing the long-term effectiveness of several antipsychotic medications, treatment with olanzapine resulted in lower rates of hospitalization for disease exacerbationReference Lieberman, Stroup and McEvoy 8 , Reference Haro, Suarez, Novick, Brown, Usall and Naber 9 and higher rates of remission.Reference Takahashi, Nakahara, Fujikoshi and Iyo 10 , Reference Novick, Haro, Suarez, Vieta and Naber 11 Time to all-cause discontinuation was also consistently longer for olanzapine compared with other antipsychotics across multiple studies. 7 –Reference Haro, Suarez, Novick, Brown, Usall and Naber 9 , Reference Kinon, Liu-Seifert, Adams and Citrome 12 , Reference Kishimoto, Hagi, Nitta, Kane and Correll 13 Despite its established efficacy, olanzapine is associated with a risk of significant weight gain,Reference Lieberman, Stroup and McEvoy 8 , Reference Allison, Mentore and Heo 14 , Reference Leucht, Cipriani and Spineli 15 which has limited its overall clinical utility.Reference Berkowitz, Patel, Ni, Parks and Docherty 16 , Reference Ketter and Haupt 17 OLZ/SAM is intended to preserve the antipsychotic efficacy of olanzapine while mitigating olanzapine-associated weight gain.

The antipsychotic efficacy of OLZ/SAM and its effect in mitigating olanzapine-associated weight gain has been reported previously in two phase 3 trials of 4-weekReference Potkin, Kunovac and Silverman 18 and 24-weekReference Correll, Kahn and Silverman 19 durations, respectively. In the 24-week study that evaluated weight gain with OLZ/SAM compared with olanzapine, body weight stabilized after the first 6 weeks of OLZ/SAM treatment, whereas continued weight gain was observed with olanzapine.Reference Correll, Kahn and Silverman 19 Given that schizophrenia is a chronic disorder requiring lifelong treatment, it is imperative to evaluate the long-term safety and tolerability of OLZ/SAM as well as its continued effectiveness in managing schizophrenia symptoms. The study described here was a 52-week open-label extension study in patients with schizophrenia who completed the 4-week acute efficacy study.Reference Potkin, Kunovac and Silverman 18 The objective was to assess the long-term safety and tolerability of OLZ/SAM in adults with schizophrenia. The durability of antipsychotic and weight mitigation effects over 1 year were also assessed.

Methods

Patients eligible for enrollment in this phase 3, multicenter, open-label extension study were the 352/401 (87.8%) who had completed ENLIGHTEN-1 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02634346), a 4-week, double-blind lead-in study assessing OLZ/SAM, olanzapine, or placebo for the treatment of adults with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia.Reference Potkin, Kunovac and Silverman 18 The extension study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02669758) was conducted between January 2016 and June 2018 at 37 sites (14 in the United States, 9 in Bulgaria, 6 in Serbia, and 8 in Ukraine) according to International Council for Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each investigational site approved the study protocol and amendments. All patients provided written informed consent.

Study design and treatment

The first visit of this study occurred within 7 days of (and including the same day as) the last visit of the lead-in study.Reference Potkin, Kunovac and Silverman 18 In order to maintain the blind in the lead-in study, all patients were started on once-daily OLZ/SAM 10/10 mg (10 mg olanzapine/10 mg samidorphan) (Figure 1). For the remainder of the study, dosing of OLZ/SAM was flexible based on patient need and investigator discretion at doses of 10/10, 15/10, or 20/10 mg. Frequent dose changes were discouraged. Study participants either continued as inpatients for up to 1 week or had already been discharged from the hospital prior to study start.

Figure 1. Study design schematic. Patients entering this study started treatment with combination of olanzapine and samidorphan (OLZ/SAM) 10/10 mg within 7 days of completing the prior 4‑week, double-blind acute efficacy study.Reference Potkin, Kunovac and Silverman 18 Patients were contacted by phone on day 3 to determine if a dose increase was needed, and, if so, an unscheduled visit was arranged mid-week 1. The olanzapine dose in OLZ/SAM could be adjusted throughout the study period, based on tolerability and investigator discretion. Prespecified visits occurred weekly for the first 2 weeks, then biweekly thereafter. After the 52-week treatment period, patients were monitored for an additional 4 weeks in a safety follow-up period or could continue receiving OLZ/SAM treatment in a long-term, open-label, follow-up safety study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03201757). aThe dose of olanzapine in OLZ/SAM could be adjusted to either 10, 15, or 20 mg throughout the study period, based on investigator discretion; the dose of samidorphan in OLZ/SAM is fixed at 10 mg.

Study visits occurred weekly for the first 2 weeks, then every other week thereafter to week 52 of the treatment period. Patients completing the 52-week study were eligible to enter a long-term, open-label follow-up safety study of 4 years in duration (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03201757). Patients who opted not to continue in the 4-year safety study entered a 4-week safety follow-up period.

Study participants

Eligible participants were adults with schizophrenia, 18 to 70 years of age, who completed the 4-week treatment period of ENLIGHTEN-1.Reference Potkin, Kunovac and Silverman 18 Key exclusion criteria included any finding that would compromise the safety of the patient or affect his or her ability to meet the visit schedule or visit requirements (based on the opinion of the investigator), use of medications contraindicated with olanzapine or that had drug-interaction potential with olanzapine, use of prohibited drugs, and women who were pregnant or nursing.

Assessments

Safety was evaluated using the following assessments: adverse event (AE) monitoring, clinical laboratory testing, vital signs, weight measurement, 12-lead electrocardiograms (ECGs), scores on movement disorder rating scales (Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale [AIMS],Reference Guy 20 Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale [BARS],Reference Barnes 21 and Simpson-Angus Scale [SAS]Reference Simpson and Angus 22), and the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)Reference Posner, Brown and Stanley 23 to evaluate for the presence of suicidal ideation or behavior. Patients were asked to fast for ≥8 hours prior to the study visits in which blood samples were drawn for laboratory testing, including fasting glucose, cholesterol, and triglycerides. Fasting status was based on self-report, without independent confirmation.

The durability of treatment effect was evaluated by Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler 24 and Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S)Reference Guy 25 scores. The proportion of patients having a response, remission, or relapse was also assessed.

Statistical analyses

Safety was assessed in all patients who received ≥1 dose of study drug. Efficacy was assessed in all patients who received ≥1 dose of study drug and had ≥1 postbaseline PANSS measurement. All efficacy and safety results were summarized descriptively based on observed data without imputation. In addition, change from baseline in PANSS total score was also summarized using last observation carried forward for missing data. Baseline for efficacy or safety analyses was defined as the last nonmissing assessment before the first dose of OLZ/SAM in this open-label extension study, and it was used for all efficacy and safety analyses, unless specified otherwise.

Response was defined as ≥30% improvement (decrease) from baseline in PANSS total score. Relapse was defined as ≥30% worsening (increase) in PANSS total score or rehospitalization for psychotic symptoms after the patient achieved stabilization. Stabilization was defined as meeting all of the following criteria: PANSS total score ≤80, and PANSS score ≤4 on P2 (conceptual disorganization), P3 (hallucinatory behavior), P6 (suspiciousness), and G9 (unusual thought content). Because PANSS item scores range from 1 = absent to 7 = extreme and a minimum score of 30 for PANSS total score represents no symptoms, responder and relapse analyses used corrected PANSS baseline scores (by subtracting 30).Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler 24 , Reference Obermeier, Schennach-Wolff and Meyer 26 Remission was defined as a PANSS item score ≤3 (mild or less) for each of 8 items in 2 consecutive efficacy assessments after the patient achieved stabilization (P1 [delusions], G9 [unusual thought content], P3 [hallucinatory behavior], P2 [conceptual disorganization], G5 [mannerisms/posturing], N1 [blunted affect], N4 [social withdrawal], and N6 [lack of spontaneity]). The time to treatment discontinuation was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method.Reference Kaplan and Meier 27 For patients who prematurely discontinued, the time to event was defined as time from the first to last dose of OLZ/SAM. All other patients were censored at the date of the last OLZ/SAM dose.Reference Goel, Khanna and Kishore 28

Results

A total of 281 patients were enrolled in this study. Of these, 277 received ≥1 dose of study drug and 248 had ≥1 postbaseline PANSS assessment. Overall, 183/277 patients (66.1%) completed the 52-week treatment period; reasons for discontinuation are listed in Figure 2. A total of 149 patients who completed the study (81.4% [149/183]) enrolled in the 4-year follow-up safety study.

Figure 2. Patient disposition. OLZ/SAM, combination of olanzapine and samidorphan; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

Demographic and baseline characteristics for all patients are presented in Table 1. The majority of patients were male (58.1%), white (78.7%), and from non-U.S. sites (72.9%). The average age of patients was 41.4 years and average weight was 79.1 kg. The majority of patients were overweight (26.7%; body mass index [BMI] ≥25 and < 30 kg/m2) or obese (29.2%; BMI ≥30 kg/m2). Mean (SD) baseline PANSS total and CGI-S scores were 78.9 (16.5) and 3.9 (1.0), respectively.

Table 1. Baseline Demographics and Disease Characteristics

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression-Severity; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; SD, standard deviation.

a Assessed in patients who received at least one dose of study drug and had at least one postbaseline PANSS assessment (n = 248).

In this study, the mean dose of olanzapine in OLZ/SAM was 15.45 mg/day. The majority of patients received a modal dose of 20/10 mg or 10/10 mg (58.1% and 41.2%, respectively). The 15/10 mg OLZ/SAM dose option was introduced ≈15 months after study initiation, resulting in few patients receiving this dose.

Safety

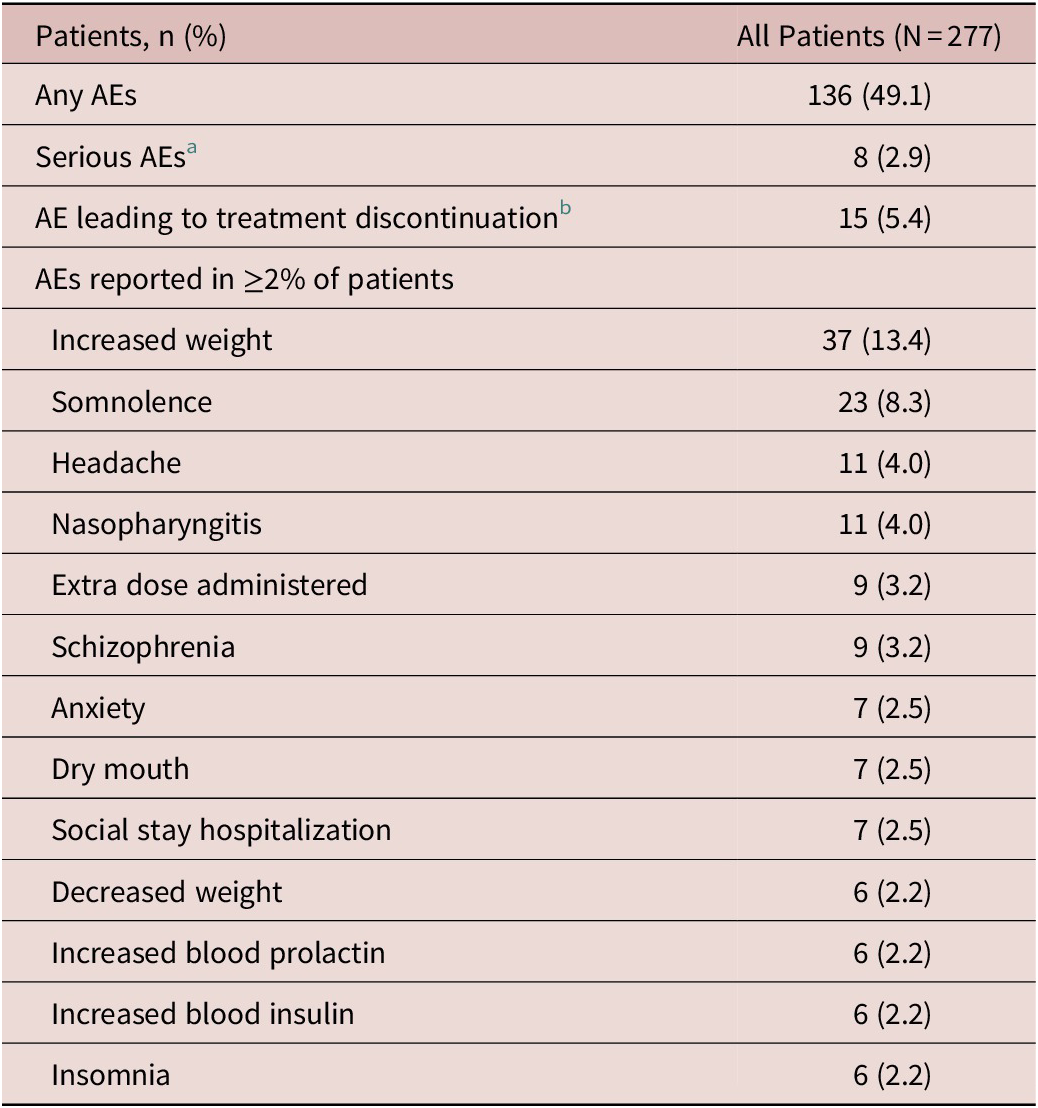

AEs were reported in 136 (49.1%) patients; increased weight and somnolence were most commonly reported (Table 2). Most AEs were mild or moderate in severity; seven patients (2.5%) experienced a severe AE. There were 10 serious adverse events (SAEs) reported in 8 (2.9%) patients (Table 2). A total of five patients (1.8%) experienced SAEs of worsening/exacerbation of schizophrenia. Two patients each had two serious AEs (intentional overdose and suicide attempt; fibula fracture and tibia fracture); a single patient reported an SAE of viral gastroenteritis. There were 15 (5.4%) patients who discontinued due to an AE. The only AE leading to discontinuation that occurred in more than 1 patient was worsening/exacerbation of schizophrenia (n = 6, 2.2%). One pregnancy was reported; the patient elected to terminate the pregnancy and was discontinued. There were no deaths in this study.

Table 2. Adverse Events Summary During the Treatment Period

Abbreviation: AE, adverse event.

a Two patients each reported two serious AEs (intentional overdose and suicide attempt; fibula fracture and tibia fracture); the other serious AEs reported were worsening/exacerbation of schizophrenia (n = 5) and gastroenteritis viral (n = 1).

b The AEs leading to discontinuation were exacerbation of schizophrenia (n = 4), worsening of schizophrenia (n = 2), and n = 1 each for the following: neutropenia, gastroenteritis viral, intentional overdose, increased blood insulin, increased glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), decreased neutrophil count, diabetes mellitus, dizziness, psychotic disorder, and suicide attempt.

Body weight

The mean (SD) weight change from baseline to week 24 (n = 208) was 1.59 kg (4.87), and to week 52 (n = 183) was 1.86 (6.69) kg, based on observed cases (Figure 3). Mean (SD) weight gain of the last on-treatment weight assessment (n = 272) was 1.26 (6.33) kg. The proportion of patients with clinically meaningful weight gain (≥7%) at any time during the study was 27.6% (75/272). The proportion of patients with weight loss of ≥7% was 11.8% (32/272). Patients who received OLZ/SAM or olanzapine in the lead-in study (ENLIGHTEN-1) had higher baseline body weight (mean [SD] baseline body weight by prior treatment: OLZ/SAM, 79.88 [16.38] kg; olanzapine, 81.79 [20.70] kg; and placebo, 75.39 [15.43] kg) and experienced less weight gain over time than patients who had previously received placebo (Figure 4A). Accordingly, a greater proportion of patients previously treated with placebo gained ≥7% body weight in this study (Figure 4B).

Figure 3. Mean (standard error, SE) body weight changes from baseline.

Figure 4. Body weight changes by visit according to lead-in study treatment (treatment received during ENLIGHTEN-1 followed by combination of olanzapine and samidorphan [OLZ/SAM] in this study). (A) Mean change from baseline in body weight. (B) Proportion of patients with ≥7% weight gain from baseline.

Lipid and glycemic parameters

Lipid parameters remained stable over the 52-week treatment period (Table 3). Changes were generally small and tended to occur within the first 24 weeks. Mean (SD) fasting glucose increased by 6.0 (14.4) mg/dL from baseline at week 52, whereas fasting insulin (mean [SD] change from baseline, −1.7 [14.8] μIU/mL) and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c; −0.07 [0.33]%) remained stable over 52 weeks.

Table 3. Mean Change From Baseline in Lipid and Glycemic Parameters by Visit

Abbreviations: HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; SD, standard deviation.

Shifts from normal to high values for total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides occurred in 8.9%, 5.5%, and 15.9% of patients, respectively. Shifts from normal to low HDL cholesterol occurred in 26.6% of patients. Shifts from normal to high values in fasting glucose occurred in 7.6% of patients (see Supplementary Table S1). Overall, 3 patients had glucose-related events that led to treatment discontinuation (n = 1 each for diabetes mellitus, increased HbA1c, and increased blood insulin).

Clinical laboratory parameters and other safety measures

Mean changes in hematology parameters from baseline to the last observed visit were generally small and considered not clinically meaningful. Two patients discontinued treatment due to nonserious AEs; one with a decreased neutrophil count and one with neutropenia. Mean changes in liver function measures were not clinically meaningful. Of three patients with any instances of abnormal liver function values, changes were transient and none met Hy’s Law criteria 29 or led to a discontinuation of treatment.

The mean (SD) change in prolactin from baseline to week 52 was 1.63 (24.65) ng/mL in women (n = 89) and −3.10 (8.70) ng/mL in men (n = 93). Among patients with normal prolactin levels at baseline and ≥1 postbaseline assessment, 29/84 women (34.5%) and 20/110 men (18.2%) had a prolactin plasma level that exceeded the normal reference range of >30 ng/mL for women and >20 ng/mL for men on at least one occasion during the study. AEs of increased prolactin were reported by six patients (all women). Gynecomastia and amenorrhea were reported as an AE in one patient each; an AE of decreased libido was reported by two patients.

No clinically meaningful mean changes were observed for vital signs or ECG findings. An abnormal postbaseline QT interval value corrected with Fridericia’s formula (QTcF) of >500 msec was recorded in 1 patient (week 36; QTcF, 564 msec); this event resolved, and the patient completed the study.

Mean (SD) changes from baseline to week 52 (n = 183) in movement scale scores were 0.0 (0.81) for AIMS total, 0.0 (0.42) for BARS global, and 0.1 (1.08) for SAS. Treatment-emergent parkinsonism (SAS total score >3) occurred in 19 (6.9%) patients, dyskinesia (AIMS score ≥ 3 on any of the first seven items, or ≥2 on two or more of the first seven items) in 7 (2.5%) patients, and akathisia (BARS global score ≥ 2) in 13 (4.7%) patients. A total of seven (2.5%) patients experienced an AE related to extrapyramidal symptoms, but none resulted in treatment discontinuation.

There were no completed suicides in this study. Five (1.8% [5/277]) patients experienced suicidal ideation, including one (0.4%) patient who experienced suicidal behavior, as determined by the C-SSRS. Suicide-related AEs were reported by five patients, including three with suicidal ideation, one with attempted suicide (overdose of 12 tablets of OLZ/SAM 10/10 mg), and one with accidental overdose (the patient pushed two tablets out of the blister pack and decided to take both).

Durability of treatment effect

In this study, the rate of all-cause discontinuation was 33.9% (94/277), with five (1.8%) patients discontinuing due to lack of efficacy (Figure 5). PANSS total scores decreased over 52 weeks, with a mean (95% CI) decrease of −16.2 (−18.5 to −14.0) (Supplementary Table S2). Similar improvements were observed with last-observation-carried-forward analysis for PANSS total score and subscale scores. CGI-S scores also improved over the treatment period, with a mean (95% CI) decrease of −0.9 (−1.0 to −0.8). Patients who had previously received placebo in the lead-in study (ENLIGHTEN-1) had the highest baseline PANSS total and CGI-S scores (84.6 and 4.3, respectively) and had the greatest improvements (−21.1 and −1.2, respectively; Figure 6 and Figure 7). Patients previously treated with OLZ/SAM or olanzapine in the lead-in study had similar baseline PANSS total scores (76.5 and 76.4, respectively) and CGI-S scores (both 3.7), and continued to experience decreases in PANSS and CGI-S scores over the 52 week study: mean changes in PANSS total and CGI-S scores were −15.6 and −0.8, respectively, for those previously treated with OLZ/SAM and −12.7 and −0.7, respectively, for those previously treated with olanzapine.

Figure 5. Time to all-cause study discontinuation. Numbers at the bottom of the figure provide the number of patients at risk at each corresponding study week.

Figure 6. Mean Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score by lead-in study treatment (treatment received during ENLIGHTEN-1 followed by combination of olanzapine and samidorphan [OLZ/SAM] in this study) and study visit.

Figure 7. Mean Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S) score by lead-in study treatment (treatment received in ENLIGHTEN-1 followed by combination of olanzapine and samidorphan [OLZ/SAM] in this study) and study visit.

The proportion of patients meeting PANSS response criteria (≥30% improvement) progressively increased throughout the study, with 32.0% (72/225), 41.9% (88/210), and 51.9% (95/183) of patients meeting response criteria at weeks 12, 24, and 52, respectively. A total of 220 patients (88.7%) achieved stabilization. Of these 220 patients meeting stabilization criteria, 129 (58.6%) achieved remission, and 23 (10.5%) experienced a relapse during the 52-week treatment period.

Discussion

In this open-label study evaluating the safety, tolerability, and durability of effect with long-term OLZ/SAM treatment in patients with schizophrenia, OLZ/SAM was generally well tolerated over 52 weeks. A majority of patients (66.1%) completed the 52-week treatment period. Patients also had sustained improvements in symptoms of schizophrenia as measured by PANSS and CGI-S scores, with the majority of patients achieving stabilization (88.7%) and not relapsing (89.5%).

Increased weight and somnolence were among the most frequently reported AEs. The most common serious AE was worsening of schizophrenia (five patients), and this was also the most common AE leading to discontinuation, consistent with other long-term open-label safety studies in this patient population.Reference Kane, Skuban and Hobart 30 –Reference Nasrallah, Earley and Cutler 34 Overall, no clinically meaningful changes were observed in ECG or vital sign measures. There were small changes in prolactin, with few prolactin-associated AEs. Extrapyramidal AEs were infrequent, occurring in seven (2.5%) patients. As measured with the AIMS, BARS, and SAS scales, treatment-emergent parkinsonism occurred in 6.9%, dyskinesia in 2.5%, and akathisia in 4.7% of patients.

Antipsychotic treatment is associated with increases in weight.Reference De Hert, Detraux, van Winkel, Yu and Correll 3 , Reference Bak, Fransen, Janssen, van Os and Drukker 35 Olanzapine is associated with the one of the greatest risks of weight gain among atypical antipsychotics, similar to clozapine.Reference Lieberman, Stroup and McEvoy 8 , Reference Allison, Mentore and Heo 14 , Reference Leucht, Cipriani and Spineli 15 , Reference Wirshing, Wirshing and Kysar 36 In addition, it has been reported that olanzapine-associated weight gain continues to increase over time.Reference Citrome, Holt, Walker and Hoffmann 37 , Reference Schoemaker, Naber, Vrijland, Panagides and Emsley 38 While weight gain is generally most rapid during the first 6 months, it can continue over multiple years.Reference Bushe, Slooff, Haddad and Karagianis 39 In long‑term studies (≥48 weeks) of olanzapine, approximately 64% of patients gained ≥7% of their body weight and 32% of patients gained ≥15% of their body weight. 40 Excess body weight has been linked to numerous serious health concerns, including an increased risk for all-cause mortality.Reference Kawachi 41 A systematic review and meta-analysis of 89 studies found statistically significant associations between obesity and incidence of type 2 diabetes, several types of cancers, cardiovascular disease, asthma, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, and chronic back pain.Reference Guh, Zhang, Bansback, Amarsi, Birmingham and Anis 42 In this study, mean weight gain was 1.86 kg in patients who completed 52 weeks of treatment with OLZ/SAM. The findings in this study suggest that, in general, weight gain with OLZ/SAM stabilizes over the first 6 weeks of treatment, with little further weight accumulation over longer durations of treatment.

Studies evaluating changes in lipid and glycemic parameters observed with olanzapine treatment in short- and long-term studies have reported mixed resultsReference Lieberman, Stroup and McEvoy 8 , Reference Citrome, Holt, Walker and Hoffmann 37 , Reference Chrzanowski, Marcus, Torbeyns, Nyilas and McQuade 43 , Reference McDonnell, Kryzhanovskaya, Zhao, Detke and Feldman 44; in real‑world settings, olanzapine treatment has a clear association with increased risk of dyslipidemia and diabetes.Reference Koro, Fedder and L’Italien 45 , Reference Koro, Fedder and L’Italien 46 In general, lipid parameters remained stable with long-term OLZ/SAM treatment. Changes were generally small and tended to occur within the first 24 weeks. Mean increases from baseline in fasting glucose were observed over 52 weeks of treatment with OLZ/SAM. In contrast, there were small (−0.07%) changes in HbA1c, a more reliable measure of long-term glycemic control that is not impacted by reported fasting status. 47 Fasting insulin levels also remained stable, and together, the data suggest that glycemic control was maintained with long-term OLZ/SAM treatment.

Olanzapine has consistently been associated with a longer time to all-cause discontinuation, a common proxy for treatment effectiveness in long-term studies of antipsychotics. 7-9 In this study, the probability of all-cause discontinuation was low, with 66.1% of patients completing the treatment period. While there was no comparator arm, this completion rate is higher than what is typically observed in similar 1-year extension studies of other antipsychotics, which average less than 50% completion.Reference Kane, Skuban and Hobart 30 –Reference Nasrallah, Earley and Cutler 34

The following limitations should be considered when interpreting these results. This study was open-label with no comparator group, which limits the conclusions that can be drawn from efficacy and safety data. Also, interpretation of findings may be impacted by missing data, as approximately one third of patients discontinued before 52 weeks. In addition, patients entering the study had received OLZ/SAM, olanzapine, or placebo in the lead-in study (ENLIGHTEN-1), which affected baseline characteristics in this open-label study. Furthermore, the fasting status of patients was based solely on self-report, without independent confirmation, and therefore, the samples evaluated for metabolic parameters may not have been truly fasting in all cases. Data from this study should be confirmed in real-world studies of OLZ/SAM treatment.

Conclusions

In this open-label extension study, long-term treatment with OLZ/SAM was well tolerated, and the majority of patients continued treatment through 52 weeks. In contrast to the persistent weight gain reported with olanzapine, treatment with OLZ/SAM was associated with early stabilization of changes in body weight after approximately 6 weeks of treatment. Similarly, metabolic parameters remained generally stable over 52 weeks. OLZ/SAM was also associated with sustained improvement in symptoms of schizophrenia and a low relapse rate. Together, these findings support the use of OLZ/SAM for long-term treatment.

Financial Support

This study was sponsored by Alkermes, Inc.

Disclosures

Sergey Yagoda, Christine Graham, Adam Simmons, Christina Arevalo, and Ying Jiang are employees of Alkermes, Inc. David McDonnell is an employee of Alkermes Pharma Ltd.

Authorship Contributions

All authors had full access to the data and contributed to data interpretation and to the drafting, critical review, and revision of the manuscript. All authors granted approval of the final manuscript for submission.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1092852920001376.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mark S. Todtenkopf, PhD, of Alkermes, Inc., who assisted in the preparation and proofreading of the manuscript, and the ALK3831-A306 Study Group. Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Gina Daniel, PhD, and John H. Simmons, MD, of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, and funded by Alkermes, Inc.