The end of the Vietnam War in April 1975 brought no peace between the United States and North Vietnam. Humiliated by a small nation, the world’s greatest power was not in a conciliatory frame of mind. In marked contrast to its generous treatment of vanquished Germany and Japan after World War II, it dealt with victorious North Vietnam as a defeated foe. US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger designed the punitive American policy. Exhausted from his arduous and immensely frustrating years of negotiating with Hanoi – and Saigon – and mortified by the outcome of the war, he harbored a strong animus against all Vietnamese. Privately, he damned the Hanoi leadership as “the most bloody-minded bastards I have ever dealt with.” He reasoned that worsening relations with China and dependence on the Soviet Union in time would force them to accede to American demands. If the United States “played it cool,” he opined, the “logic of events” would force North Vietnam to come around.Footnote 1

The War after the War, 1975–87

Without consulting Congress, Kissinger orchestrated after Hanoi’s victory in the Vietnam War a series of steps that perpetuated the conflict by other means. The day Saigon fell, the United States froze $70 million in South Vietnamese assets held by American banks. US agencies imposed an array of economic sanctions that retained the wartime embargo on North Vietnam, slapped export controls on newly “liberated” South Vietnam and Cambodia that prevented them from receiving humanitarian aid, denied Hanoi any US foreign aid and access to international capital, and even forbade shipment of agricultural equipment and medical supplies by charitable organizations. Americans could not legally travel to Vietnam. As yet another way of isolating Hanoi, the United States in the fall of 1975 vetoed its membership in the United Nations (UN), an action widely viewed as spiteful.Footnote 2

North Vietnam emerged from the war understandably hubristic. Its leaders had long proclaimed their nation the vanguard of world revolution. But they were also practical enough to recognize their vast reconstruction needs. They feared dependency on their communist allies, China and the Soviet Union, and recognized that the United States had the resources to meet their desperate needs. They fell back on a vaguely worded article in the 1973 Paris Agreement on Vietnam calling for the United States to heal the wounds of war by providing economic assistance, “reconstruction aid” by official account. Hanoi deluded itself that it had strong political support in America. Its haughty manner and talk of US “obligations” to provide what amounted to reparations as a precondition to discussions of normalization further inflamed top US officials. Most galling were its claims that the United States must provide aid in order not to “lose face.”Footnote 3

The positions staked out by both sides in the summer of 1975 set the parameters for the generally fruitless diplomacy of the next decade. Kissinger candidly admitted that “I gag at the thought of economic aid to Vietnam.”Footnote 4 The Gerald Ford administration flatly rejected Vietnamese demands, claiming that Hanoi’s repeated violations of the 1973 agreement absolved the United States of any responsibility to abide by its terms. Contradicting itself, Washington used another article of that agreement to pin on North Vietnam responsibility for Americans missing in action (MIA). Percentage-wise, the United States had far fewer MIAs in the Vietnam War than in World War II or Korea. Many of the missing were air-crew members who went down in remote areas with rugged terrain, making the location and identification of remains all but impossible. For the loser of a conflict to hold the winner responsible for its MIAs was quite unprecedented in the history of warfare. But President Richard M. Nixon had used the MIA issue to rally Americans behind continuation of the war, and in time that had taken on a life of its own. Reversing the US position on aid, Hanoi held that America’s refusal to uphold its “obligations” relieved it of responsibility for MIAs. Each side accused the other of “bribery” and “blackmail.”Footnote 5

Sporadic efforts to break the deadlock ran afoul US electoral politics. In late 1975, the Vietnamese returned nine Americans captured at the end of the war. The United States responded by allowing a nongovernmental organization (NGO) to send humanitarian aid to Vietnam. Again, there was talk of normalization, and Hanoi promised to release the remains of some Americans killed in action (KIA). But its absorption of South Vietnam and creation of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRVN) in the summer of 1976, along with its shift closer to the Soviet Union, cooled US interest. Seeking election in his own right and facing a tough rightwing challenge from California governor Ronald Reagan, Ford, in campaign speeches, denounced Hanoi’s leaders as a “bunch of international pirates,” denied any intention of establishing diplomatic relations, and demanded a “full accounting” of MIAs as a precondition to talks. Perhaps to head off another UN veto, the Vietnamese softened their position in October by requiring only that Ford stop calling them “pirates.” The thaw quickly refroze when the United States, shortly after the election, again wielded the veto in the Security Council, a move Democrat Jimmy Carter, Ford’s opponent and the winner of the election, fully backed.Footnote 6

A neophyte in politics and diplomacy, Carter brought to the presidency high hopes for peacemaking. He dreamed of ending the Cold War. He hoped to heal the wounds of America’s recent, traumatic conflict by making peace with Vietnam, a step that could also stabilize Southeast Asia and keep Vietnam out of the Chinese and Soviet orbits. He dropped the Kissinger–Ford demand for a full accounting of MIAs, asking only for a “satisfactory report.” He opened cracks in the embargo by allowing some private humanitarian and development aid for Vietnam and by easing the travel ban. He dispatched to Vietnam a special mission to discuss normalization and related issues, a move that – briefly – raised hopes for further progress by establishing an office in Hanoi to deal with MIA matters.Footnote 7

While the United States turned conciliatory, Hanoi moved in the opposite direction. At the 4th Party Congress in late 1976, First Secretary Lê Duẩn’s regime shifted hard left by imposing a Stalinist economic model on the newly unified country. In foreign policy, the Vietnamese set out to improve relations with their feuding allies, the Soviet Union and China, and to assume a “leadership” role in Indochina. Still hubristic, they insisted that the United States could heal itself only by providing them what amounted to reparations. Mistakenly persuaded that the United States needed Vietnam more than they needed US aid and that American public opinion was behind them, they took a harder line on normalization issues.Footnote 8

Throughout 1977 and into 1978, the two sides engaged in an “awkward dialogue of mutual misunderstanding and increasing diplomatic tension.”Footnote 9 The United States remained confident that Vietnam would soften its stance on aid, while Hanoi wrongly believed that Washington would have to provide assistance. During extended off-and-on talks in Paris, the United States agreed to drop its opposition to Vietnam’s admission to the UN if Hanoi would push ahead with an accounting of MIAs. To the shock of US diplomats, the Vietnamese publicly reintroduced the aid issue by releasing a 1973 Nixon letter promising $3.25 billion and embarrassing the Carter administration at home. Congress responded by banning aid to Vietnam. US diplomats pushed Vietnam on MIAs and sought to disconnect that issue from normalization. Vietnam continued to demand aid as a precondition to negotiations. By December, the talks in Paris had deadlocked. The revelation of Vietnamese spying in the United States provoked outrage that further narrowed the room for compromise. The “scars of war still exist on both sides,” US Secretary of State Cyrus Vance lamented.Footnote 10

In 1978, the lagging discussions on normalization became entangled in the frantic geopolitical maneuvering that rekindled the Cold War and sparked fighting in Indochina. The roles were now reversed, with an increasingly embattled Vietnam as the eager suitor and the United States as the standoffish object of its attention. In Indochina, the murderous Cambodian regime of Pol Pot, wary of Vietnam’s claims to a “special relationship,” conducted border raids, provoking Vietnamese counterattacks. Vietnam blamed China for Cambodian provocations and edged closer to the Soviet Union. On the verge of war with Cambodia and possibly China, and despite its close ties with the Soviet Union, Vietnam now eagerly sought ties with the United States, again proposing to move immediately toward normalization and address other issues later. The Vietnamese were “panting to lock up the deal,” one US official observed.Footnote 11

Washington spurned Hanoi’s advances. Soviet adventurism in the Horn of Africa had provoked anger and rising suspicion in the United States. As the staunchly anti-Soviet National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski gained predominance among Carter’s advisors, the administration took a harder line against the USSR and sought to “play the China card” against Moscow by moving closer to Beijing. Vietnam’s ties with Moscow and enmity with China made it less attractive to the United States. China made plain its opposition to US ties with Vietnam. Following Brzezinski’s lead, the administration decided to hold off on normalization with Vietnam until the rapprochement with China had been finalized. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and Carter’s angry and forceful response brought Soviet–American tensions back to the heyday of the Cold War.Footnote 12

A series of dramatic events in 1978–9 would put normalization on the shelf for a decade. As fighting raged across Indochina in 1979, diplomatic stances hardened. Vietnam signed a treaty with the Soviet Union in November 1978 just before it invaded Cambodia and settled in for a long-term occupation. Seeing the sinister hand of Moscow behind Vietnamese actions, China provided aid to Cambodia, speeded up negotiations with the United States, and in February invaded Vietnam’s northern provinces. This largely symbolic maneuver proved costly and was quickly liquidated after Beijing claimed to have “taught Vietnam a lesson.” Meanwhile, Vietnam’s harassment of its Hòa population – the ethnic Chinese – set off another mass exodus of refugees into China and Southeast Asia, sparking protests throughout the region and fueling anti-Vietnamese sentiment in the United States. With China the higher priority, Washington now insisted that Vietnam’s close ties with Moscow, occupation of Cambodia, and maltreatment of the Hòa stood as barriers to normalization. The diplomatic ties that seemed possible, if not likely, when Carter took office were not even on the horizon when he left.Footnote 13

US attitudes hardened significantly in the 1980s. Republican President Ronald Reagan campaigned on a Cold War platform. Upon taking office, he hyped up anti-Soviet rhetoric, ordered a massive defense buildup, and took a hard line in negotiations on nuclear weapons. After a time of national amnesia, the Vietnam War roared back into American life with a vengeance. A “revisionist” school of thought challenged the “dove” orthodoxy. Reagan pronounced Vietnam a “noble cause.” Former military and civilian leaders insisted that the United States could have won the war had it used its vast power decisively, an argument designed to cure the so-called Vietnam syndrome that allegedly limited America’s use of military power abroad. The continued arrival of “boat people” from Vietnam and its invasion of Cambodia put a moral stigma on Hanoi.Footnote 14

Sparked by reported sightings of live Americans behind the so-called Bamboo Curtain, the POW/MIA issue emerged front and center in Reagan’s first term. Sensationalist films such as Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985) fed the myth of Americans held captive by Indochinese communists and desperate to be rescued by US superheroes. A potent POW/MIA lobby kept up a drumfire of criticism of Hanoi – and Washington. Americans wore wristbands in memory of the forgotten. A stark, black-and-white POW/MIA flag soon flew above the White House, the US Capitol, and other public buildings (and still flies in many places today). Reagan brought to the cause his unique brand of sentimental patriotism. He viewed resolution of the MIA issue as a way to erase the nation’s “crippling memory” of Vietnam. Responding to the surge of popular interest, he assigned it the “highest national priority” and reasserted demands for a full accounting. He even approved covert operations into Laos by soldiers of fortune of dubious reputation searching for Americans held captive.Footnote 15

Normalization, 1988–2007

Yet another stunning global geopolitical upheaval and major changes in the United States, and especially in Vietnam, finally set these former enemies on a mutually wary course toward normalization. In the United States, the harder the MIA lobby pushed, the more it alienated leaders of both political parties. Reagan administration officials grew increasingly angry with its agitation, and skeptical of its numbers, and tired of its insistence that the war could not end until “all POWs came home.” More important, Reagan’s quite remarkable shift from belligerency against the Soviet Union to détente opened up new possibilities with Vietnam. After years of stasis, the administration in 1987 sent General John Vessey to Vietnam as a special emissary to discuss MIAs and other issues.Footnote 16

For Vietnam, the transformation was far more dramatic – and drastic. By the early 1980s, hubris was in short supply in Hanoi. The invasion of Cambodia had bogged down in a costly, quagmire-like occupation, “Vietnam’s Vietnam,” some Americans smugly called it. Enmity with the United States and China left Hanoi isolated and dependent on Moscow. The grand economic experiment launched with such zeal by the communist regime a decade earlier had flopped miserably, leaving Vietnam one of the world’s poorest nations. Economic growth lagged at around 2 percent, annual per capita income averaged $100, and inflation soared. “Waging a war is easy,” the veteran revolutionary Phạm Vӑn Đồng conceded, “but running a country is difficult.”Footnote 17

External pressures played a critical role in the transformation. While Vietnam languished economically, its Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) neighbors showcased glittering economic success. Under reformer Deng Xiaoping, China in the mid-1980s introduced quasi-capitalist reforms to salvage a sagging economy – and perpetuate Communist Party rule. Premier Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika (restructuring) of the Soviet system provided a further stimulus and alternative. As part of the revolution in world affairs he did so much to bring about, Gorbachev also pressed Hanoi to reconcile with China and the United States. A more compelling incentive came with a drastic Soviet aid cut that threatened a body blow to Vietnam’s already teetering economy. The fall of communist regimes in Eastern Europe at the end of the decade and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union sent shock waves across the world, reaffirming to the Hanoi government that it must do better by its own people or risk the fate of its communist allies.Footnote 18

Economic woes, more than anything else, forced radical changes in Vietnam. Party leaders increasingly recognized that they must find ways to bolster economic growth and improve living standards. Food shortages and even famine in the 1980s underscored the danger. Acting on the slogan “reform or die,” a regime led, ironically, by Southerners forced out the combative – and dogmatic – Lê Duẩn (who died in 1986) after twenty-five years in power, traded communist ideology for a more pragmatic economic and diplomatic approach, and launched a program of Đổi mới (Renovation). The changes took place incrementally rather than all at once. Not surprisingly, they provoked opposition within the government. While enacting reforms, the party clung tightly to political power and stifled dissent.Footnote 19

At home, the reformers took radical steps to stimulate economic growth and prosperity. Relying on Southerners experienced with the workings of a capitalist economy, they scrapped collectivization, especially in agriculture, and downplayed central planning. They limited government price-fixing in favor of supply-and-demand principles and market incentives, and encouraged private ownership, while putting state-run enterprises on a profit basis and freeing them to operate on their own. These changes put a premium on opening Vietnam to foreign investment and finding new trading partners. The reforms began slowly, but in the wake of the dramatic events of 1989 the regime boldly – and keenly aware of the risks – stepped up the process by embarking “on an uncharted path without a clear idea of the ultimate destination.”Footnote 20

Economic change compelled a fundamental reorientation of Vietnam’s foreign policy. The reformers prioritized economic growth over military security and enacted huge cuts in a swollen military budget. Party Resolution 13 of 1988, a “seminal moment,” according to scholar David Elliott, spoke of a “changing world” and called for “new thinking,” words often used by Gorbachev. The reformers swapped ideology for a foreign policy based on national interest and abandoned classic Marxist doctrine of a world divided into two camps for interdependence and “multidirectionalism.” After years of colonial control and dependence on outside powers, an isolated Vietnam aimed for a self-reliance based on the “three nos”: no military alliances; no foreign bases on Vietnam’s soil; and no military actions against other nations. Its leaders attempted to promote their nation’s security and prosperity and maximize its autonomy by shortening its list of enemies, expanding the number of its friends, and affiliating with international organizations – what they called “pro-active international integration.” This fundamental reorientation of policies, along with the sharp drop in Soviet aid and decline in trade with Eastern Europe, made it essential for Vietnam to withdraw from Cambodia, reconcile with China, normalize relations with the United States to get rid of the crippling embargo, develop ties with Western Europe and Japan, and gain access to ASEAN. As a first step in this process, the SRVN responded to the Vessey mission by turning over to the Americans 130 sets of remains, a crucial turning point in postwar US–Vietnam relations. An issue that had been an impediment now helped jumpstart the process of normalization.Footnote 21

Reagan’s successor, George H. W. Bush, went along, but set a steep price. During its first years in office, the Bush administration was preoccupied with the end of the Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and war in the Middle East. In this strikingly different international context, enmity toward Vietnam seemed increasingly outdated, even irrelevant. Leaders of both the main US political parties agreed it was time to move on. In what has been called America’s “unipolar moment,” that brief time when the nation stood as the lone superpower, hubristic US officials were not in a mood for conciliation. In 1991, the administration charted a harsh “Road Map” of demands for normalization: When Vietnam withdrew from Cambodia, granted access to its archives dealing with MIA matters, and agreed to the establishment of an MIA office in Hanoi, the United States would end its trade embargo. As MIA issues were resolved, the two nations could proceed toward normalizing their diplomatic relations. “One day Vietnam may overcome the consequences of having won its war against America,” the London Economist opined. “The Americans are putting off this day as long as possible.”Footnote 22

The Vietnamese naturally resented the tone of the road map and the severity of its demands. “America is a beautiful lady,” one diplomat moaned, “but very hard to please.” But with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Vietnamese lost their patron, and their economic reforms made ties with the United States almost mandatory. They consented to US demands, even (remarkably) to archival access, a step Bush hailed as a “real breakthrough” in “writing the last chapter of the history of the war.” The United States in turn provided $1.3 million to help Vietnamese disabled by the war, lifted its ban on travel to Vietnam, permitted American businesses to negotiate contracts with the SRVN, and allowed Vietnamese Americans to wire money to relatives in Vietnam. The two nations seemed on the verge of full normalization when Bush’s campaign for reelection stymied further progress.Footnote 23

Completion of the process was left to Bush’s successor, Democrat and former Arkansas governor Bill Clinton. By the time Clinton took office, American businesses were clamoring for an end to the embargo and access to Vietnamese markets. After a thorough investigation, a Select Senate Committee headed by Vietnam veterans John McCain (Republican and a former POW) and John Kerry (Democrat and former Vietnam Veterans Against the War protestor) produced no evidence that Americans were being held captive in Indochina. Opinion polls indicated firm support for normalization, if not outright enthusiasm. Clinton still moved cautiously. His protest against the war as a college student and his avoidance of the draft had been contentious issues during the 1992 campaign. Like his predecessors, he hesitated to provoke a still potent MIA lobby. His relations with his own military were especially bad, giving him added reason for caution. In July 1993, the administration stopped blocking international loans to Vietnam and began stationing diplomats in Hanoi to help American families seeking information about missing service personnel. Finally, in February 1994, Clinton lifted the embargo, and the two countries set about establishing liaison offices in their capitals.Footnote 24

The immediate results in terms of trade were limited. Boeing, United Airlines, and American Express rushed into Vietnam, and Pepsi and Coke launched “cola wars” to win over Vietnamese palates. Some thirty US companies opened offices the day after the embargo was lifted, starting a new battle for Vietnamese wallets. Nike quickly became Vietnam’s largest foreign employer. But a cumbersome Vietnamese bureaucracy, along with rampant corruption and stifling red tape, posed major obstacles to investment and development. By 1999, the United States ranked only eighth among foreign investors. High tariffs on Vietnamese goods sold in the United States and Vietnam’s lack of most-favored-nation status restricted what it could sell, thus limiting its ability to buy US goods. In any event, Vietnam did not have much to sell, and a low per capita income sharply restricted what it could buy. US exports averaged only $300 million from 1996 to 1999.Footnote 25

Full normalization came in 1995. In a major symbolic act, the Vietnamese returned to the United States the now crumbling and rotted-out embassy in Hồ Chí Minh City, once an imposing, fortress-like symbol of America’s presence in Vietnam, subsequently a lingering image of its frenzied departure and humiliating defeat. In January 1995, the two nations agreed to open liaison offices in Washington and Hanoi. Finally, in July, Clinton announced his intention to establish full diplomatic relations on the grounds that opening Vietnam to US trade and ideas would help promote freedom there, as in Eastern Europe. Vietnamese leaders resented America’s patronizing tone and worried about the corrupting influence of American materialism, but they had little choice except to go along. In an act richly symbolic of the spirit of reconciliation, the United States subsequently sent to Hanoi as its first ambassador Douglas “Pete” Peterson, a former POW who had previously visited the city as an involuntary guest at the notorious “Hanoi Hilton.” An inspired choice, Peterson went out of his way to promote friendship and reconciliation with his former captors. In a technical sense, at least, the war had finally ended.Footnote 26

A visit to Vietnam by President Clinton in November 2000, the first trip there by an American chief executive since Richard Nixon visited troops in 1969, pushed the process of normalization still further. Clinton stayed four days, longer than customary for such visits, and the SRVN, in an act without precedent, permitted his speech to be broadcast over national television. He did not apologize for the war, as some Americans and Vietnamese had urged, recognizing the obvious domestic political pitfalls of such an act. But he showed sensitivity to Vietnamese feelings. The theme of his visit was “Vietnam is a country, not a war,” an obvious fact that Americans in their self-absorption had difficulty grasping. “The history we leave behind is painful and hard,” he affirmed. “We must not forget it, but we must not be controlled by it.” He visited a site where Americans and Vietnamese together painstakingly sifted through dirt in search of fragments of bone that might help identify Americans. He also expressed concern for the thousands of Vietnamese still missing and provided thousands of pages of documents to help the search. In Hanoi and Hồ Chí Minh City, he drew huge crowds. His visit represented a sort of closure for one era and the beginning of another.Footnote 27

The visit also exposed lingering sores in the United States and Vietnam. “Why didn’t he go before?” some US veterans snarled, making clear the continuing divide between those Americans who went to Vietnam and those who did not. The Vietnamese insisted that the United States should assume greater responsibility for the deaths and injuries caused by unexploded land mines and Agent Orange. When Clinton gently chided the Vietnamese government about its human rights record and pressed it to permit greater freedoms and open itself fully to globalization, Vietnam’s communist leaders charged that an imperialist United States was once again seeking to impose its will on a sovereign nation.Footnote 28

By the turn of the century, Đổi mới had brought dramatic changes to Vietnam. The country’s annual growth rate averaged between 6 and 8 percent, and it managed to lift itself from the ranks of the world’s poorest countries into middle-income status. Poverty and hunger were no longer acute. Vietnam in fact produced enough food to export some products. An explosion of jobs in factories significantly altered Vietnamese society. Living standards improved, and by 2009 per capita GDP reached $1,200. In foreign policy, the changes were little short of revolutionary. Normalization with the United States was but a single element of Vietnam’s “multidirectional” foreign policy. In 1985, it had diplomatic relations with only twenty-three nations. Ten years later, the number had jumped to 163. It also reconciled with China and established ties with Japan and numerous European nations. It joined ASEAN and Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), a twenty-one–nation forum founded in 1989 to promote free trade in the region. It also became a nonpermanent member of the UN Security Council.Footnote 29

During the first years of the new century, Vietnam–US economic ties expanded dramatically. The United States became a major investor in Vietnam, and that nation became one of the largest recipients of American foreign assistance, much of it going to AIDS/HIV prevention and treatment, deactivating unexploded mines and shells, and education. The two nations concluded a bilateral trade agreement. In 2007, with full US support, Vietnam joined the World Trade Organization (WTO), and Congress agreed to full and normal trade relations. The United States soon became Vietnam’s largest market, in 2009 taking in about 20 percent of that nation’s exports. Two years later, trade totaled $1.76 billion, a tenfold increase since 2001, with the balance heavily in favor of Vietnam. Trade representatives met frequently to discuss areas of contention, such as American charges that Vietnam was not protecting intellectual property rights and was dumping clothing and other products on the US market at lower prices than domestic and foreign competitors.Footnote 30

One of the most vexing items in US–Vietnam trade has been the lowly catfish market competition that provoked the so-called “catfish wars” between southern American catfish farmers and Vietnamese exporters. Following ratification of the trade treaty, catfish exports to the United States soared, and Vietnam captured some 20 percent of the US market. Catfish farmers from Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Arkansas naturally blamed Vietnamese competition for their sharp drop in sales. They mounted a public relations campaign against catfish “with a foreign accent” that sought first to taint Vietnamese fish as an inferior and even dangerous product raised in the heavily polluted Mekong River that might even contain Agent Orange (which Americans, of course, had sprayed in Vietnam). When the smear campaign failed to slow Vietnamese imports, the Americans claimed that Vietnamese catfish were not in fact catfish and gained legislation forcing them to be labeled basa or tra, no more like a catfish than “calling a cat a cow,” a sympathetic US legislator claimed. When that also failed, southern catfish farmers secured the imposition of tariffs on imports. Vietnamese exporters showed the same persistence and staying power in waging the catfish wars as their brethren did in the earlier war. Critics noted the contradiction between Americans’ efforts to impose free-trade principles on other countries while violating those principles to stamp out competition.Footnote 31

“Legacy” issues from the war continued to divide the two nations. Vietnam’s quite extraordinary assistance in helping locate the remains of American MIAs (usually in return for substantial economic assistance) provoked its own people to complain that hundreds of thousands of their sons were also missing “and you are looking for Americans.” Through technology and searches in its records, the United States began helping to find Vietnamese MIAs.Footnote 32 For years, the Vietnamese pressed the United States to accept responsibility for and assist in cleaning up the deadly mess left from the estimated 20 million gallons of herbicides sprayed across roughly 10 percent of the South Vietnamese countryside and in treating the millions of Vietnamese victims of American dioxins. For liability reasons, the United States refused to accept legal responsibility. Since 2007, it has provided substantial funds for dioxin removal and health care for victims. In 2012, fifty years after the start of the Ranch Hand spraying operations, it agreed to remove dioxin from the site of its former air base in Đà Nẵng, an arduous $43 million project that would take six years – “the first steps to bury the legacies of our past,” the US ambassador called it.Footnote 33 Some Vietnamese agreed; others complained of too little, too late. A follow-up project at the former US air base at Biên Hòa began some years later.

Human rights issues have also loomed large in US–Vietnamese relations. Vietnam has changed significantly since the implementation of Đổi mới. Individuals can engage in private enterprise. Vietnamese enjoy a limited freedom of worship, and church membership has increased. To promote tourism, the government even approved the construction of a decidedly bourgeois string of golf courses running north to south called the Hồ Chí Minh Golf Trail.Footnote 34 Đổi mới also opened the door at least slightly for individuals and a growing number of quasi-political organizations to agitate for such things as greater freedoms and better working conditions, and even to challenge government policies. And the Internet has provided protestors a potentially powerful weapon of dissent.Footnote 35 To the consternation of some Americans, Vietnam remains very much a one-party authoritarian state. The party’s strategy has been to permit some freedoms but to crack down hard on any dissent that threatens its control. It has specifically targeted minority groups in the Central Highlands and the northwest mountain regions. Press freedoms have been restricted and bloggers shut down, and even sometimes incarcerated. The roughly 2 million Vietnamese in the United States, some of them quite prosperous and many of them critical of the Hanoi regime, have lobbied Washington to push the Vietnam government to allow additional political and religious freedoms. Some Americans have sought to use trade to leverage change in Vietnam. Congress and human rights groups regularly introduce legislation to punish the SRVN for political repression.

“Not Too Hot, Not Too Cold”: From Normalization to Partnership

Changes in the international system and in the positions of the two nations, along with the emerging threat of China, pushed the former enemies toward measured and still qualified cooperation on security and military issues. America’s unipolar moment turned out to be stunningly brief. Terrorist attacks on New York and Washington on September 11, 2001 provoked a US “global war on terror” that in turn produced ill-advised, drawn-out, and ultimately disastrous and debilitating military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq. The Great Recession of 2008 further undermined America’s global position – and its claims to offer a political and economic model for other countries. The United States remained the world’s greatest power economically and militarily, but a nation that had seemed invincible in the 1990s appeared anything but in the new century.

The major catalyst for US–Vietnam defense cooperation was the looming presence of Asia’s new economic giant and rising military power: China. While the United States was bogged down in Iraq and crippled by recession, China surged economically and began to rebuild its military, especially its navy. It still lagged far behind the United States in overall military power, but it increasingly asserted itself in the Asia–Pacific region, especially in the South China Sea. That vital waterway carries an estimated $5 trillion in trade each year, one-third of global commerce. It contains a bounty of fish and vast deposits of oil and natural gas. China’s neo-imperial claim to “indisputable sovereignty” over the entire region, what it calls its “patrimony,” threatened the interests that Vietnam and other small regional nations such as the Philippines and Malaysia consider vital. To back up its claims, China occupied some disputed islands and constructed upon reefs numerous artificial islands with runways capable of handling large military aircraft. It harassed and even seized fishing boats from Vietnam and other regional nations.Footnote 36

Vietnam’s policies have mirrored its historical love–hate relationship with its former colonial master and larger northern neighbor. Its economic reforms are patterned loosely on those of China. China is its largest trading partner. But the two countries have clashed over numerous issues. Vietnam has protested Beijing’s plans to build enormous hydroelectric dams on the Upper Mekong River, a waterway vital to its economy and ecology. It fears rising Chinese influence in Laos, traditionally part of its area of influence. The SRVN’s awarding of a contract permitting Chinese companies to mine bauxite in the Central Highlands provoked fierce opposition from Vietnamese environmentalists, academics, intellectuals, and veterans’ groups, including even the legendary General Võ Nguyên Giáp of Điện Biên Phủ fame. Chinese harassment of Vietnamese fishing vessels in the South China Sea in 2007 and the government’s refusal to respond set off widespread and angry protests in Vietnam’s major cities and among bloggers. Hanoi has been careful not to provoke Beijing, but it has also come to see strategic value in a larger US presence in Southeast Asia and closer ties with its former enemy.Footnote 37

To meet the China threat and other foreign policy challenges, Vietnam in the early years of the new century expanded and refined the multidirectional policy adopted in the 1980s. In an increasingly multipolar world, it sought to build its economy and safeguard its security by engaging with as many nations as possible. Eschewing alliances in accord with the “three-nos” policy, it sought a “hedging” strategy that would protect it from depending on any one nation or getting caught up in conflict between great powers. The device chosen to achieve its goals was the strategic partnership, a concept apparently adapted from the business world that gained wide popularity among small and middle-sized nations, especially in the Asia–Pacific region. These bilateral agreements were goal-driven rather than threat-driven. They spelled out sometimes in great detail areas of cooperation and goals to be pursued in trade, security, and defense, and even cultural and educational activities. They sought to promote the nation’s interests without the binding commitments of a formal alliance. The partnerships came in ascending levels of “density” that sometimes seemed murky: comprehensive; strategic-comprehensive; and comprehensive-strategic. Vietnam’s first partnership was a comprehensive-strategic agreement with Russia in 2001 weighted heavily toward defense and arms purchases. By 2017, it had various levels of partnerships with twenty-six nations. Its comprehensive-strategic-cooperative partnership with China spelled out in great detail numerous areas of “cooperation” to balance known areas of “struggle” between the two nations.Footnote 38

The United States also had extensive trade with China, and China held much of its soaring national debt. As a Pacific power, it too was uneasy about China’s assertive claims and its bullying of smaller nations. Some US military strategists warned of the dangers of China’s growing military power, especially its navy. Entangled in costly and futile wars in the Middle East since the turn of the century, America’s presence in the Pacific had diminished. In a major 2010 policy shift, President Barack Obama announced a US “pivot” back to an area traditionally important to the United States and likely to be central to world commerce in the twenty-first century. Later that year, in a tough speech at an ASEAN meeting in Hanoi, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton surprised her listeners, especially the Chinese, by asserting that freedom of the seas was a vital national interest for the United States. While offering to mediate China’s disputes with regional nations, she further warned that the Obama administration would not tolerate the threat or use of force by any claimant. The United States subsequently challenged China’s extravagant claims with air and sea patrols, sparking the kind of incidents that could easily escalate.Footnote 39

Against this backdrop of rising regional and great-power tension, the United States and Vietnam moved cautiously toward growing, but still limited, cooperation on defense and security issues. Hanoi continued to emphasize the “multidirectional” approach in its foreign relations. Wary of the reliability of American commitments, and even of a US–China rapprochement, as in the 1970s, it did not seek a close relationship. With memories of colonial domination still etched in its mind, it clung firmly to its “three nos” policy. It carefully avoided any step that would antagonize its neighbor. But it sought by edging closer to the United States to gain some leverage against Beijing and even possibly some influence with Washington. Relations with both China and the United States should follow a “Goldilocks Formula,” one Vietnamese diplomat observed: “not too hot, not too cold.”Footnote 40

For the United States, also, discretion has been the watchword. It too has avoided actions that might antagonize China. It publicly justified its move toward Vietnam with reasons other than China. It may also have hoped that closer relations with Vietnam would give it some influence over Hanoi’s internal politics, especially in regard to human rights.

From 2011, the two nations inched closer together. As part of its “pivot” back to Asia, the United States upgraded its defense ties with numerous Asia–Pacific nations, Vietnam included. US Navy ships began regular visits to Vietnamese ports. The two fleets participated in joint nonmilitary exercises; their officers exchanged visits to Hanoi and Honolulu. In 2011, Vietnam and the United States signed a “landmark” Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on bilateral defense cooperation, pledging to work together in such areas as maritime security, search and rescue, humanitarian assistance, and disaster relief, thereby establishing a foundation for their military cooperation to the present.Footnote 41

Discussions of a strategic partnership exposed the persisting complexity of the evolving US–Vietnam relationship. In diplomatic parlance, those two words affirm that the signatories have formed ties that each considers important for the attainment of its vital interests. A strategic partnership usually includes a plan of action for the achievement of shared goals and may even discuss the means to attain them. US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton proposed such an agreement as early as 2010. But negotiations got bogged down, in part, apparently, because of Vietnam’s concern regarding American pressures on human rights issues and its fear of alienating China. In July 2013, during the visit of Vietnam’s President Trương Tấn Sang to Washington, the two nations announced agreement on a Comprehensive Partnership (CP). Apparently, they considered a less formal agreement better than none at all. The CP mainly restated areas of cooperation already agreed upon, such as working together to combat terrorism, international crime, and piracy.Footnote 42

Relations warmed significantly in Obama’s second term. Visits of top officials to each country became a regular occurrence. In a 2012 event rich with symbolism, US Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta traveled to Cam Ranh Bay, a magnificent deepwater port once the site of one of America’s largest overseas naval bases. The first visit to the United States of a General Secretary of the Vietnamese Communist Party, Nguyễn Phú Trọng, in July 2015, was viewed by Vietnamese as an especially important event. Hanoi had lobbied hard for it, and some top officials chose to interpret it as tacit US acquiescence in their one-party rule. Vietnam allowed the entry of additional American Peace Corps volunteers, most of whom taught English. The number of US students in Vietnam rose significantly.Footnote 43

Chinese aggressiveness in the South China Sea in the summer of 2014 aroused furious opposition in Vietnam. Beijing deployed an enormous oil rig in waters claimed by Vietnam and sent 100 ships to protect its operations. When Vietnam dispatched coast guard vessels to the area in a show of force, Chinese ships rammed some of them and used water cannons against their crews. This incident fueled anti-Chinese rage in Vietnam, provoking noisy but peaceful demonstrations in major cities and violent protests among workers who destroyed some Chinese-owned factories and demanded lessening their nation’s dependence on China. To secure international backing, the government invited foreign journalists to visit the scene of conflict. Claiming to have achieved its goals, China in time vacated the area, but the incident left grave concern in Vietnam.Footnote 44

This crisis brought Hanoi and Washington still closer. In October, initially on a case-by-case basis, the United States modified the arms embargo first imposed on North Vietnam in 1964 and reapplied to the SRVN twenty years later as a ban on the sale of weapons to countries (mostly communist) deemed threats to world peace. Initial purchases were limited to maritime security and included such items as defensive weapons for Vietnam’s coast guard.

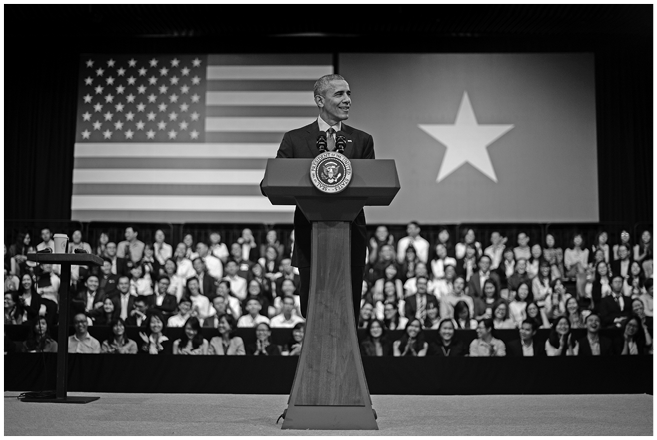

A capstone event came in May 2016 with Obama’s visit to Vietnam. The president drew large crowds at most of his stops. He won robust applause for his affirmation that “big nations should not bully smaller ones.” As part of his visit, the United States lifted all restrictions on arms purchases, a step Vietnamese leaders hailed as “clear proof that both countries have completely normalized relations.” In explaining his decision, the president pointedly avoided references to China, instead insisting that the United States was shedding “relics of the Cold War,” as with its opening to Cuba. Removal of the arms embargo was more important symbolically than substantively, since Vietnam lacked money for major purchases and preferred Russian weapons that were often cheaper and that they were more accustomed to. The United States reportedly hoped to get from Vietnam assent for its troops and ships to rotate through major ports, especially Cam Ranh Bay. The two nations signed an updated statement on cooperation. During his visit, Obama also announced the establishment of Fulbright University in Hồ Chí Minh City, a private, nonprofit educational institution founded by Harvard University, the only school in Vietnam where the curriculum was not set by the government. Obama’s visit also exposed lingering tensions on human rights. Dissidents were not allowed to attend the president’s speeches, and he himself publicly expressed “concern” about such issues.Footnote 45

Figure 17.1 US President Barack Obama speaks at the Young Southeast Asian Leaders Initiative town hall event in Hồ Chí Minh City (May 25, 2016).

A Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) sponsored by the Obama administration seemed likely to bring the two nations even closer economically. The TPP was a cornerstone of the US pivot to Asia. It included eleven Asia–Pacific nations representing 40 percent of the global economy, and it comprised the world’s largest free-trade zone. Vietnam saw the TPP as easing its dependence on trade with China. Membership would also give its clothing, shoe, and textile producers free access to US markets. The United States viewed the TPP as a means to challenge Chinese dominance in the region. It could also be used to prod Vietnam on human rights, and in fact Vietnamese admission was conditioned on pledges to prevent child and forced labor, permit unionization of workers, and set minimum wages. US–Vietnam trade reached an all-time high of $42 billion in 2016. Vietnam retained a sizable trade surplus of $32 billion.Footnote 46

The surprising election in 2016 of the political newcomer, Republican Donald J. Trump, posed uncertainties and challenges for the budding US–Vietnam relationship. The new president campaigned on a platform more assertively nationalist and unilateralist than any since the 1930s, pledging to shut off immigration into the United States and negotiate trade agreements more favorable to US workers while questioning the value of alliances and threatening, at a minimum, to force allies to pay more for their own defense. Upon taking office, Trump plunged ahead with his America First program, attacking multilateral trade agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and Obama’s TPP, raising questions about US treaty ties with South Korea and even the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and in time launching trade wars with Canada, Mexico, and China. He railed against Vietnam’s sizable trade surplus with the United States and made clear the United States would not join the TPP, threatening to deprive Vietnam of its favored position in the US market. The administration’s position on China veered wildly during Trump’s first years in office, leaving uncertainty in Hanoi.Footnote 47

Trump’s rabidly nationalist shift undercut the US–Vietnam relationship less than seemed likely. His approach to foreign policy left little room for promoting human rights and encouraging democracy. On the contrary, he cozied up to authoritarian leaders like the Philippines’ Roberto Duterte, Egypt’s Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, and especially Russia’s Vladimir Putin. His administration cut off aid to Cambodia for alleged human rights abuses but said nothing about Hanoi’s arrest of protesting bloggers and religious leaders. This eased, if it did not eliminate altogether, a major area of friction in US–Vietnam relations. Despite Trump’s refusal to join the TPP and his complaints about America’s $32 billion trade deficit with Vietnam and intellectual property issues, Vietnam’s trade with the United States actually increased to $27.44 billion in the first six months of 2018. And the TPP nations are determined to proceed without the United States. China’s allegedly unfair trade practices with Vietnam and its continued assertiveness in the South China Sea added powerful incentives for good relations with the United States. President Xi Jinping vowed to stand “tall and firm in the East” and insisted that China would not “lose one inch” of territory in the region. Meanwhile, the Chinese pushed ahead with new artificial islands on reefs and shoals scattered throughout the Spratly Islands and elsewhere in the region. Trump ordered the navy to assert US claims vigorously, and American warships sailed on “freedom of navigation” patrols, raising the possibility of major clashes. In October 2018, no doubt partly with the off-year elections in mind, Vice President Mike Pence firmly asserted that “We will not stand down.”Footnote 48

In this context, US–Vietnam relations remained close. Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyễn Xuân Phúc was the first Southeast Asian leader to meet with Trump. The president in turn visited Vietnam in November 2017 as part of the APEC forum meeting in Đà Nẵng. Trump’s America First rhetoric rattled his hosts, but their concern about China made good relations with the United States mandatory. The United States provided a coast guard cutter and six patrol boats to help defend that part of the South China Sea that Vietnam claimed as its own. In the summer of 2018, for the first time, Vietnam actively participated in RIMPAC (rim of the Pacific) military exercises in Hawai’i and California with twenty-five other nations. A major symbolic event in March was the appearance in Đà Nẵng of the massive aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinsson. The length of three football fields and with a crew of 6,000 sailors, the giant nuclear warship represented the “epitome of modern naval power.” Its visit to Vietnam seemed to affirm in the most tangible way America’s continued presence in the region.Footnote 49

Conclusion

At the end of 2018, trade issues remained contentious. In the first eight months of the year, Vietnam had a surplus of more than $25.74 billion, a concern to the Trump administration and possible obstacle to a new bilateral treaty. The president encouraged Vietnam to make up the deficit with purchases of US weapons, but that seemed unlikely in light of Russian dominance of that market. The catfish wars continued to simmer, American producers protesting what they saw as Vietnamese dumping, Vietnamese complaining about US regulations limiting importations of their fish. Vietnam continues to seek US and WTO recognition of its status as a “market economy.” Americans insist that this will not happen while state-owned businesses remain privileged. Trump would go no further than delegate the matter to a working group.Footnote 50

In the realm of strategy and geopolitics, Vietnamese and US interests have increasingly converged, in scholar Carlyle A. Thayer’s apt words, but they are not congruent. The two nations share an interest in Vietnam’s stability and security. In the face of the Chinese threat, Vietnam values its partnerships with the United States and many other nations, and appreciates America’s naval presence in the region. But the “three nos” policy limits how close such ties can become. Vietnam carefully avoids steps that might antagonize Beijing. Only in the event of a dire and immediate threat would it welcome US military forces on its soil or ships in its harbors. Vietnam fears getting caught in a struggle between the two superpowers. For its part, the United States sees Vietnam as a possibly useful partner in limiting Chinese expansion in the Indo-Pacific region. But it is not likely to assist Vietnam in the event of a direct Chinese threat. The two nations have come a long way from the recriminations of the immediate postwar period and the studied wariness of normalization. For the moment, at least, they are content to keep their relations “not too hot, not too cold.”Footnote 51