Psychiatrists are routinely asked to assess people detained in police custody. Assessments are often undertaken as an emergency and usually as part of an on-call rota. Doctors may vary in experience and seniority and include staff grades, senior trainees and consultants. Assessments may be requested for a number of different purposes, including screening for mental disorder, advising on management, assessing for the purposes of mental health legislation and providing medico-legal advice in respect of a police investigation into a crime. In England and Wales, the majority of assessments will be undertaken on those detained under Section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983. Other assessments will be on those initially arrested for a crime or a public order offence but for whom there is subsequent concern about their mental health. Medicolegal advice is often requested to determine an individual's fitness to be interviewed by the police as part of their investigation into a crime.

Although this article examines this important and often difficult arena of psychiatric practice with reference to the UK, and England and Wales in particular, many of the issues discussed are relevant to psychiatrists practising anywhere.

Epidemiology

People in contact with the criminal justice system at all stages, including at the initial point of arrest, have a high rate of psychiatric morbidity, as previously reported in Advances (Reference ReedReed 2002). The available evidence indicates that of those with a disorder, many have serious mental illness or other major mental health problems. For example, Reference Shaw, Creed and PriceShaw et al (1999) in a study from Manchester found that, of those detained overnight in police custody, 6.6% had serious psychiatric disorder (schizophrenia, psychoses, hypomania, depressive disorder and generalised anxiety disorder), 17.4% had alcohol dependence and 15.7% had drug dependence.

A lack of services

A major review of mentally disordered offenders in London, by the Revolving Doors Agency (1996), suggested that there is a high level of contact between the police and people with mental health problems but such contact often does not lead to access to healthcare. Reference JamesJames (2000) highlighted failures in provision of care for those with mental disorder who present to police custody. He noted a lack of coordination of agencies, a lack of training of custody sergeants, delays in legal processing, delays in the arrival of appropriate professional personnel and a lack of training of forensic medical examiners. Lord Bradley, in his review, noted that although there is a high prevalence of mental disorder among those who present to the police, there is often a lack of service provision for this highly vulnerable group (Rt Hon Lord Bradley 2009). He found that such services were not commissioned by the National Health Service and made it a key recommendation that services be improved and diversion from custody be established where appropriate.

The statistics

The mental health needs of people with intellectual disability (known as learning disability in UK health services) detained in police custody have been subject to only a limited amount of research. Almost 1% of detainees who presented to an inner-city police station in Belfast were judged to have a possible or definite intellectual disability; many had complex mental health needs, with high levels of self-harm and alcohol and substance misuse (Reference Scott, McGilloway and DonnellyScott 2006).

People with substance misuse problems detained by the police are rightly regarded as a vulnerable population with considerable health needs. Reference Bennett and HollowayBennett & Holloway (2004) estimated that 69% of detainees test positive for illicit substances.

Pathways to care

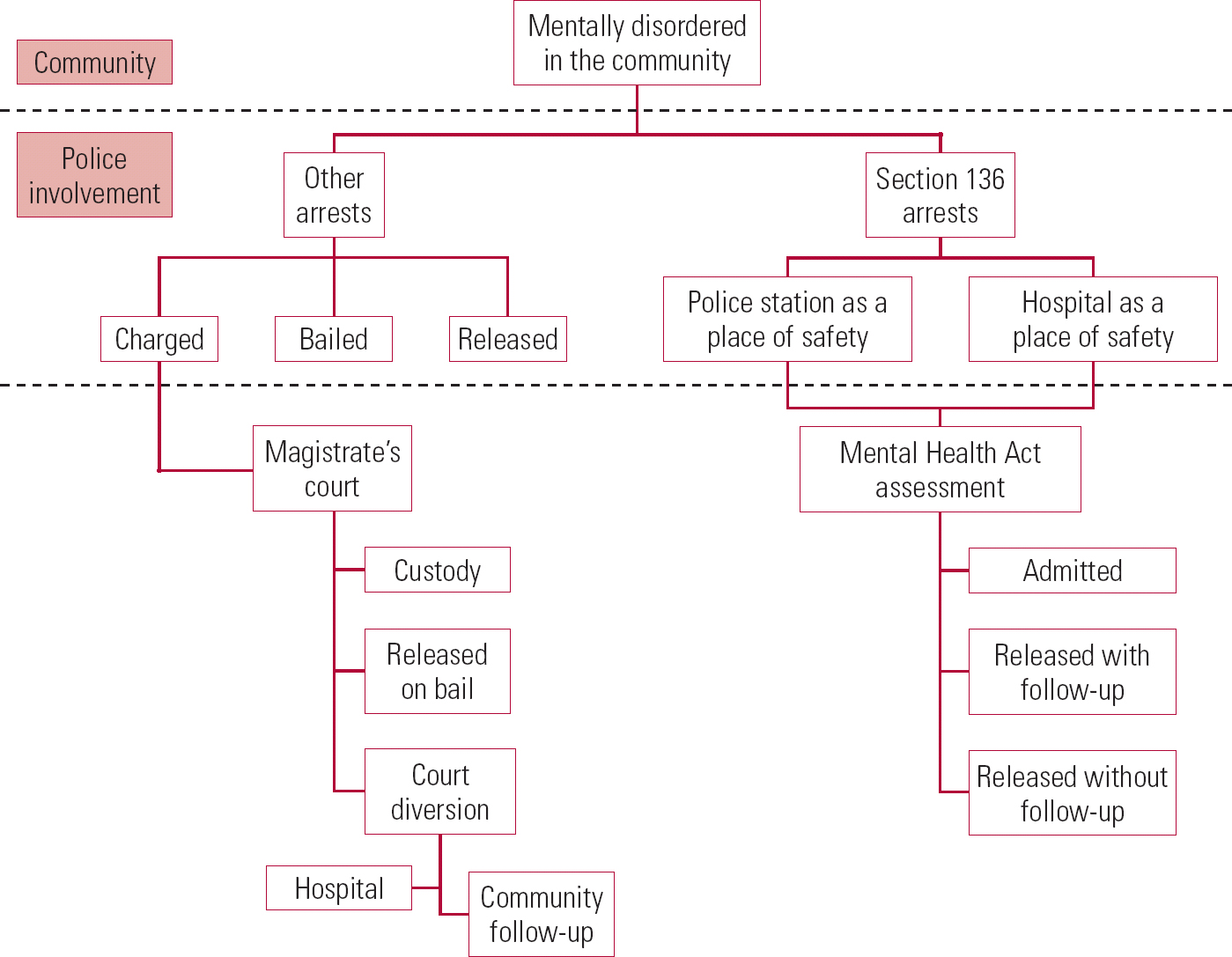

There are numerous pathways to mental health-care for people with mental disorder. Typically, psychiatric referrals originate from a general practitioner or a hospital emergency department. However, for a significant number the route to care is via the police, usually under the provisions of Section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983. In addition, a number of people arrested for notifiable crimes and non-notifiable offences such as breach of the peace or public disorder exhibit mental disorder.

When the police are involved in the management of mentally disordered people it is often to deal with those who present with behavioural disturbance and those who otherwise lack insight and do not self-refer to helping agencies.

In a study of first-episode psychosis, Reference Morgan, Mallet and HutchinsonMorgan et al (2005) found that less than a third of patients had initiated help-seeking. They also found that criminal justice agencies were involved as a source of referral to psychiatric services in about a quarter of their total cohort.

There is no reliable information on the total number of people with mental illnesses who come into contact with the police in the UK. Section 136 accounts for a significant proportion of such contact. The Independent Police Complaints Commission report into the use of Section 136 (Reference Docking, Grace and BuckeDocking 2008) found that 17 400 people were detained in England and Wales under Section 136 during the year 2005–06. It is unknown whether numbers entering the pathway to care via the police and Section 136 is increasing, remaining stable or decreasing.

There has been a fourfold increase in the number of people detained under Section 136 between 1996 and 2006 for whom a hospital was used as a place of safety, perhaps reflecting the provision of new resources (Information Centre for Health and Social Care 2007). In spite of the increase in the use of the hospital environment as a place of safety, this still accounts for only about a third of all Section 136 assessments, even though it has been government policy since 1990 that a hospital is the preferred place of safety for such assessments.

Reasons for police involvement

Section 136 of the Mental Health Act allows for detention by the police of people in a public place who appear to have a mental disorder and who are in need of immediate care or control. For those with mental disorder it is a key point of contact with the police and an important link with psychiatric services.

The use of Section 136 has been heavily criticised by various commentators, including the mental health charity Mind. It has been said that the police are poorly trained to detect and manage mental disorder. There is a lack of procedure nationally on the use of this order, with widespread regional variation, and it has been found that Black and minority ethnic groups are detained at a much higher rate, leading to accusations of racism in the police force (Reference Rogers and FaulknerRogers 1987). A later study (Reference BrowneBrowne 1997) into the operation of the civil sections of the Mental Health Act found that police officers are prone to associating Black people with risk factors.

It appears to be rare for the police to have initiated contact with a person suspected of having a mental disorder: in most cases members of the public, relatives or other statutory agencies such as social services are responsible for the police involvement. Reference RogersRogers (1990) found that the police become involved when there is a perception of threat or actual violence to people or property and when other community services, such as general practitioners or social services, have not responded when called upon by relatives or neighbours.

Social disadvantage, unemployment, lack of stable accommodation, belonging to a minority ethnic group, lack of general practitioner and past psychiatric history have been identified as associated with increased detention under Section 136 (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2008).

Mental illness can cause significant behavioural disturbance, which can lead to police intervention (Reference Johnstone, Crow and JohnsonJohnstone 1986). Severe mental illness can also cause social disintegration and exclusion and contributes to a multitude of severe social problems that are associated with police involvement.

Legal aspects and use of Section 136

When considering the legal aspects of Section 136, it is worth remembering its exact wording (Box 1). Unlike for other sections of the Mental Health Act, there is no statutory form for the police to complete when detaining a person under Section 136, although the Royal College of Psychiatrists has recommended that such a form be introduced (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2008). Therefore, the basic standards that operate are that the police officer alone makes a determination, i.e. a reasonable belief (Reference JonesJones 2006: p. 509), that the person has a mental disorder (without the need for evidence) and needs immediate care and control. This allows for potential use of force by the police. Even if its criteria are met, the police are not obliged to use Section 136. In a number of police forces, other powers to detain are used, including breach of the peace (Reference Docking, Grace and BuckeDocking 2008). Nevertheless, it has been shown that the police appear to be able to successfully identify mental disorder using Section 136 and that the majority of those detained under it are subsequently admitted to hospital (Reference Rogers and FaulknerRogers 1987).

BOX 1 Section 136 – Mentally disordered persons found in public places

-

(1) If a constable finds in a place to which the public have access a person who appears to him to be suffering from mental disorder and to be in immediate need of care or control, the constable may, if he thinks it necessary to do so in the interests of that person or for the protection of other persons, remove that person to a place of safety within the meaning of Section 135 […].

-

(2) A person removed to a place of safety under this Section may be detained there for a period not exceeding 72 hours for the purpose of enabling him to be examined by a registered medical practitioner and to be interviewed by an approved social worker and of making any necessary arrangements for his treatment or care.

Defining a ‘place of safety’

The Mental Health Act 1983, as amended in 2007, now provides the option of transferring a person detained under Section 136 to another place of safety (Box 2), after which there are time constraints, with limits on detention of up to 72 hours. This lapses as soon as the person has been examined by a registered medical practitioner, if the assessment concludes that the person detained does not have a mental disorder. This length of time was originally thought necessary to enable assessment by both an approved social worker and a registered medical practitioner. The time allowed for detention has led to fierce criticism, particularly as in many cases the place of safety is police custody. The Mental Health Act Commission (2005) recommended that the holding powers relevant to police stations should be limited to 12 hours. However, no change has been made as it is considered that in some parts of the country it could prove difficult to obtain the assessments in a shorter period. The College recommends that the police station as a place of safety should be used only as a last resort and that assessment by a doctor should start within 3 hours (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2008).

BOX 2 A ‘place of safety’, as defined in subsection 6 of Section 135

‘Place of safety’ means residential accommodation provided by a local social services authority under Part III of the National Assistance Act 1948 or under paragraph 2 of Schedule 8 to the National Health Service Act 1977, a hospital as defined by this Act, a police station, a mental nursing home or residential home for mentally disordered persons or any other suitable place the occupier of which is willing to receive the patient temporarily.

Custody as a place of safety

Once an individual is detained in a police station, it is the custody sergeant who has the responsibility for processing them and who is legally responsible for ensuring their well-being. The role of the custody officer in respect of those detained is defined by the revised Codes of Practice of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984. Code C states, ‘the custody officer shall determine whether the detainee is or might be in need of medical attention’. It also states that they must determine whether the detainee is likely to pose a significant risk to themselves, and to do this, the custody officer may need to consult an appropriate health professional, who in many cases will be a forensic medical examiner or a psychiatrist.

If a detainee is suspected of being mentally disordered or otherwise mentally vulnerable, the police must arrange for an appropriate adult (Box 3) to be present at interviews or other formal procedures. They must also arrange that those detained under Section 136 are assessed as soon as possible by a registered medical practitioner and an approved social worker. In practice this will lead to a request for psychiatric assessment.

BOX 3 An appropriate adult

-

• A relative, guardian or other person responsible for [the detainee's] care or custody;

-

• Someone experienced in dealing with mentally disordered or mentally vulnerable people but who is not a police officer or employed by the police [such as an approved social worker as defined by the Mental Health Act 1983 or a specialist social worker];

-

• Failing these, some other responsible adult aged 18 or over who is not a police officer or employed by the police.

Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984: Code C, para. 1.7(b)

Limitations

It has been repeatedly stated that police stations are no place to assess or care for individuals with potentially serious mental disorders (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2008). The facilities in police stations are not designed for the assessment and management of those with mental illness and the police are not trained in mental healthcare. Treatment is not authorised under Section 136 of the Act and there is a substantial risk that patients' health will deteriorate or their suffering will continue unnecessarily.

The Independent Police Complaints Commission Commissioner Ian Bynoe said:

Police custody is an unsuitable environment for someone with mental illness and may make their condition worse, particularly if they are not dealt with quickly, appropriately and don't receive the care they need. The continued use of cells not only diverts police resources from fighting crime, but criminalises behaviour which is not a crime. A police cell should only be used when absolutely necessary, for example when someone is violent, and not as a convenience. [Independent Police Complaints Commission 2008]

In 2004, the Joint Parliamentary Committee on Human Rights (2004: section 7, para. 220) stated:

People requiring detention under the Mental Health Act should not be held in police cells. Police custody suites, however well resourced and staffed they may be, will not be suitable or safe for this purpose, and their use for this purpose may lead to breaches of Convention rights. In our view, there should be a statutory obligation on healthcare trusts to provide places of safety, accompanied by provision of sufficient resources for this by the Government.

The Independent Police Complaints Commission report into the use of Section 136 (Reference Docking, Grace and BuckeDocking 2008) found that twice as many people were detained in police custody as a place of safety than in hospitals.

Ethnicity of the detainees

There is no doubt that there is an excess rate of detention among Black and minority ethnic groups, which is a major cause of concern for service users, health service providers and policy makers. Several studies have identified over-representation of Black and minority ethnic groups among those detained under Section 136.

Reference Singh, Greenwood and WhiteSingh et al (2007), in their systematic review of 49 studies exploring the differences within and between ethnic groups who are detained under the Mental Health Act 1983, found that compared with White patients, Black patients were 3.83 times, Black and minority ethnic patients 3.35 times and Asian patients 2.06 times more likely to be detained. Various explanations for this included misdiagnosis, discrimination, higher rates of psychosis and differences in illness expression. However, they found that these explanations were not adequately explored and needed further research.

Reducing ‘disproportionate rates of compulsory detention of Black and minority ethnic users’ is a key aim of the government report Delivering Race Equality in Mental Health Care (Department of Health 2005).

Substance misuse

Several studies have noted a high prevalence of substance misuse among those arrested by police. Reference Bennett and HollowayBennett & Holloway (2004) found that 69% of detainees in 16 police custody suites across England and Wales tested positive for at least one illicit substance. Reference Payne-James, Wall and BaileyPayne-James et al (2005) found that 30% of police station detainees in London were dependent on heroin or crack cocaine. Significant mental health problems (e.g. schizophrenia) were present in 18% of those detainees. Substance misuse and severe mental illness may coexist, causing particular problems in identification and management.

Illicit drugs and alcohol are significant contributors to deaths in custody. A Home Office study (Reference Leigh, Johnson and IngramLeigh 1998) found that substance misuse was associated with 25% of all deaths in police custody in England and Wales. Some deaths were due to the direct consequences of drugs, alcohol or a combination of both, for example poisoning or aspiration of vomit. Detainees with substance misuse present many problems and clinical challenges. There are associated risks from self-harm or suicide, mental health problems, intoxication and withdrawal states and often significant behavioural changes. Apart from the difficulties in general management of these detainees, problems may also arise in assessing fitness for interview.

Over the years a number of reports have been produced to assist in the management of detainees with substance misuse in police custody. These include detailed clinical guidelines for the management of substance misuse detainees (Association of Forensic Physicians 2006). Although these detainees are largely attended by forensic medical examiners, psychiatrists may be asked to assess them where there is a question of psychiatric illness or fitness for interview.

Substance misuse on its own does not provide sufficient grounds for hospital admission under the Mental Health Act. However, the Act may be appropriate for those with mental disorder and those in whom mental disorder is either associated with or precipitated by substance misuse.

If there are concerns, attending psychiatrists should consider all the details relevant to the detainee's presentation, especially in police custody, where information related to the detainee's health is likely to be minimal. They should also pay particular attention to suicidal or self-harming intent.

Diversion schemes

Government policy has been to divert mentally disordered offenders away from the criminal justice system wherever possible, as previously observed in this journal (Reference ReedReed 2002). The development of police and court diversion schemes has tried to address this need whether or not prosecution runs in parallel.

Opportunities for treatment

Police stations as the first point of contact provide an opportunity to initiate assessment and treatment of mentally disordered detainees. Over the past three decades there have been considerable developments in the diversion of mentally disordered people from the criminal justice system to care. This diversion to care can happen at different levels, including police stations, courts and prisons (Reference JamesJames 2000). Court diversion schemes can help only detainees who have been charged and brought before the courts. They cannot be the solution for those detainees with mental illness who are filtered out of the system at an earlier stage and therefore do not reach court (Fig. 1).

Significant numbers of detainees arrested by the police for non-notifiable offences, including breach of peace, begging, alcohol-related offences and public order-related offences, have mental disorders. They are not arrested under the provisions of Section 136 and therefore there is no automatic mental health assessment (Reference Docking, Grace and BuckeDocking 2008). Some detainees are released on bail; others are cautioned and released whether they are considered to be mentally ill or not. Despite the high level of contact between the police and people with mental health problems, it does not always lead to access to health and social care (Revolving Doors Agency 1996).

Police station diversion schemes

Psychiatric custody diversion schemes at police stations have received relatively little attention over the years, even though for many mentally ill people they are the first point of contact leading to psychiatric care. It appears that few such schemes have been developed in the UK, although there are some notable exceptions. Reference JamesJames (2000) described the operation of a police station diversion scheme in central London. Experienced community psychiatric nurses used semi-structured interviews to assess referrals from the police custody sergeant or the forensic medical examiner. The patients were rated for global severity of illness, given a likely diagnosis and, where necessary, referred for appropriate health service involvement. The scheme proved that successful diversion occurred and that care was arranged either by way of admission or community care for a group who it appeared otherwise would not have received psychiatric care. Of those referred, 31% were admitted to hospital and 44% of those not admitted were referred on to community services. A similarly successful scheme in Birmingham was described by Reference Riordan, Wix and Kenny-HerbertRiordan (2000), with community psychiatric nurses providing a 24-hour service, 7 days a week. Successful recognition of those with mental disorder has led to early diversion and provision of care. Diversion from custody can work effectively only where there is a range of integrated services.

Magistrates' courts diversion schemes

Magistrates' courts diversion schemes have been more widely developed, with about 150 such schemes across England and Wales (Nacro 2005). The survey by Nacro (an independent voluntary organisation working to prevent crime) reported that where such schemes exist they are generally effective in terms of diversion from custody and referring people to suitable community care.

Deaths in custody

Death in police custody is a rare event. In England and Wales each year, about 30 people die in or following policy custody (Reference Docking and MeninDocking 2007). The majority of these deaths are linked to substance misuse or mental health needs. An analysis of deaths in custody in England and Wales between 1998 and 2002 showed symptoms of mental illness in 42% of cases (Reference Best, Havis and StrathdeeBest 2004).

Another study across England and Wales, covering a period of 9 years (Reference Leigh, Johnson and IngramLeigh 1998), found that the single most common cause of death in police custody was self-harm, accounting for about a third of deaths. Substance misuse and medical conditions accounted for more than half of the remaining deaths.

It is important to understand that detainees with mental illness are more at risk in custody. Attending psychiatrists should always bear in mind that the police are not trained in mental health. Reference Leigh, Johnson and IngramLeigh et al (1998) identified lapses in communication between doctors, police officers and other professionals involved. When psychiatrists are called to assess detainees in police custody, it is essential to ensure that any self-harm, suicide and other risks identified are recorded clearly and communicated well to police officers, forensic medical examiners and any other health professionals involved in the assessment or care of the detainee.

Fitness to be interviewed

All aspects of fitness to be interviewed have been reviewed in detail in Advances (Reference Ventress, Rix and KentVentress 2008). The psychiatrist needs to understand that determination of fitness for interview is essentially an assessment of capacity to see whether an individual can fully participate in a police interview and be able to produce reliable information. The psychiatrist must ensure that the interview process will not lead to harm or deterioration as well as ensuring proper safeguards for detainees.

At a practical level the considerations in Box 4 will assist the psychiatrist in determining a police detainee's fitness to be interviewed.

BOX 4 Practical considerations that will assist in determining a police detainee's fitness to be interviewed

Background information

-

• Is the person intoxicated or have they recently taken drugs or alcohol?

-

• Do they have a known psychiatric history?

-

• Are there any known physical health issues either recent or in the history?

-

• Is there a history of poor educational achievement, e.g. a statement of special educational needs?

-

• Is there anything in the nature of the detainee's behaviour that causes concern either at the time of the arrest or subsequently?

Capacity assessment

-

• Does the person understand why they are at a police station?

-

• Do they know that they are to be interviewed?

-

• Do they understand the purpose of interview, i.e. that they are suspected of committing a crime?

-

• Do they understand the police caution? (which may be explained in more simple terms)

-

• Can they understand what is being asked?

-

• Do they appreciate the significance of any answers they give?

-

• Are they capable of deciding whether to answer a particular question?

Significance of mental disorder (adapted from Reference Ventress, Rix and KentVentress 2008)

-

• A person with intellectual disability might be fundamentally unable to understand their rights.

-

• Depressive disorders may lead to false confession owing to abnormal feelings of guilt. The person may not comprehend or appreciate the significance of questions.

-

• Hypomania can cause the person to lack an understanding of the significance of what is being asked. It may lead the individual to make exaggerated statements or false claims because of elation or ebullience. People with hypomania are extremely unlikely to be fit to be interviewed.

-

• Psychotic conditions may render someone unfit, e.g. if the person is deluded about the content of the question or if they are thought disordered or if they are distracted or perplexed. It should also be noted that an individual with a psychosis may be perfectly capable of providing a reliable police interview, i.e. one that is accurate and not affected by mental disorder.

-

• People with organic disorders such as confusional states, including toxicity or severe drug and alcohol withdrawal, are unlikely to be fit to be interviewed. The capacity of a person with dementia will depend on the degree of impairment.

Duties of the attending psychiatrist

An attending psychiatrist has a range of responsibilities when called upon to assess a person detained in police custody (Box 5). The following case vignettes help to illustrate the complexity of making such an assessment.

BOX 5 Roles and responsibilities of a psychiatrist asked to assess a person detained in police custody

-

• Understand what is being requested: to provide a Mental Health Act assessment; to provide advice on risk and management; or to assess fitness to be interviewed.

-

• Gather all information available: examine the nature and manner of arrest; review custody records; gain access to any health records (where practical); and talk to the police officer and any person who has accompanied the detainee to gather information, for example, concerning behaviour before arrest and in custody, use of substances, any psychiatric history (especially self-harm) and any information to suggest intellectual disability.

-

• Request an interpreter if there is no common language between you and the detainee.

-

• Obtain consent unless the person lacks capacity (when best interests to proceed must be demonstrated) or when assessing for the purposes of the Mental Health Act.

-

• Interview in private if circumstances allow (after considering safety issues). Some detainees may have been extremely violent and present immediate risks to personal safety.

-

• Full psychiatric assessment is essential if at all possible. There may be circumstances where it is not possible, e.g. the detainee is intoxicated or manic or otherwise severely psychotic, confused or behaviourally disturbed. Detailed mental state examination is always required, including an appropriate cognitive examination. Ensure a physical examination has been undertaken.

-

• Carry out a thorough risk assessment and document it clearly. The purpose of risk assessment is to provide information to appropriately manage the individual. Risks of self-harm, suicide and harm to others must be clearly identified. Factors to be taken into account in risk assessment include history of violence, substance misuse, presence of antisocial personality characteristics and acute psychotic symptoms (e.g. command hallucinations, violent thoughts, thoughts of suicide or self-harm and any history of these).

-

• When undertaking Mental Health Act assessments it is essential to liaise with a social worker and a second medical practitioner, e.g. a forensic medical examiner. Liaison with a specialist may be required, e.g. for intellectual disability or child and adolescent assessments

-

• Assess fitness to interview as detailed above and advise on the need for an appropriate adult.

-

• Liaise with a hospital to arrange for appropriate placement if admitted or detained. The results of the risk assessment will be crucial in determining whether someone is admitted to open or secure psychiatric facilities. Ensure that appropriate transport is arranged. Arrange follow-up, e.g. with community mental health teams.

Handling information

-

• Make detailed records. The custody records are not medical records. However, a timed and dated entry in these records is required with information about where to access the detailed clinical record. Your name and designation should be printed and signed and contact details provided. The clinical record should be appropriately kept with the person's health records and that information becomes subject to confidentiality requirements.

-

• Keep the detainee informed at all stages unless this is not in their best interests

-

• Give clear verbal feedback to the forensic medical examiner and custody officer or the person in charge of the investigation and record all feedback.

Case vignette 1

A 56-year-old woman arrested for shoplifting is reported to have a poor memory. The questions for the psychiatrist include:

-

• Does she have a mental disorder (e.g. dementia, confusional state, intoxication, depression, psychosis or intellectual disability)?

-

• Is she fabricating poor memory? A capacity assessment is essential to determine her fitness to be interviewed.

-

• Does she need an appropriate adult? She will need one if she is found fit to be interviewed but deemed to have a mental disorder.

-

• Does she need psychiatric care and follow-up and should this be in an in-patient or an out-patient setting?

-

• Can she be diverted from custody? The police could bail her without charge pending further investigation or she could be charged and appear before a magistrate. She could then be bailed, in which case psychiatric care can either be arranged voluntarily (in hospital or the community) or she could be detained under Part 2 of the Mental Health Act. The magistrate could remand her in custody.

Case vignette 2

A 26-year-old man is reported to have killed his mother. He is known to have had a previous diagnosis of schizophrenia. Vital questions for the psychiatrist include:

-

• Is he currently psychotic?

-

• Is he fit to be interviewed? A functional capacity assessment is vital: even though he may have delusions he could still be fit to be interviewed in the presence of an appropriate adult.

-

• Is he in need of urgent psychiatric care?

-

• Could he be diverted from custody? A comprehensive risk assessment is vital not only in terms of risk to others but also to himself. If diversion is appropriate, should this be to a secure psychiatric unit?

Case vignette 3

A 40-year-old man is detained at a police station under Section 136 of the Mental Health Act. He was found naked and singing loudly on a street. He could be transferred to a hospital as an alternative designated place of safety. The psychiatrist must ask:

-

• Does he have a mental disorder (e.g. mania)?

-

• Is his mental disorder complicated by substance misuse?

-

• Is detention necessary?

Training issues

Any psychiatric assessment in police custody calls for the highest standards of history-taking and examination, supplemented by the careful consideration of relevant information from appropriate written and oral sources. However, as Reference Protheroe and RoneyProtheroe & Roney (1996) found, there may be no formal training available in assessing fitness for interview and such assessments are commonly requested of on-call psychiatrists.

We believe that full training in the management of detainees in police custody is important for all psychiatric trainees, although it is usually advanced psychiatric trainees who undertake such assessments. The competencies required of psychiatrists will be those necessary for any detailed and complex psychiatric assessment but there are specific competencies in terms of knowledge and skills required for working in this arena:

-

• effective communication and liaison with members of the multidisciplinary team

-

• knowledge of the links between psychopathology and behaviour

-

• knowledge of the effects of substance misuse

-

• knowledge of relevant legislation (e.g. the Mental Health Act 1983, the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE), the Human Rights Act 1998, and the Mental Capacity Act 2005)

-

• risk assessment and management

-

• capacity assessment

-

• assessment of fitness to be interviewed

-

• knowledge of appropriate service provisions for diversion from custody.

Training should encompass clinical, legal and ethical aspects of dealing with this difficult and challenging area of psychiatric practice. To achieve the competencies the following should be part of a training programme:

-

• supervised exposure to assessments in police custody, including out of hours (when the majority of such referrals take place)

-

• regular supervision to formally review such cases

-

• feedback and assessment of competencies

-

• mechanisms for gaining theoretical knowledge to include academic meetings and case presentations

-

• governance to include audit and incident reviews.

It is vital for any psychiatrist to have sufficient experience to gain understanding of matters relating to people detained in police custody. Whether it is the variety of issues (such as Section 136 assessments), effects of substance misuse or assessment of fitness for interview of the detainee, the psychiatrist has a significant role that must not be underestimated.

Conclusions

Significant numbers of people with mental disorder present to the police and for many this is their only route to psychiatric care. Psychiatrists and other healthcare professionals have a vital role in the assessment and management of such people whether in the course of emergency on-call work or through formal diversion schemes.

It is encouraging that the numbers of Section 136 assessments in hospitals as a place of safety have increased over the past decade as better provisions have been developed. However, this represents only a third of such assessments. The police station remains an unsuitable environment for those with mental disorder and yet it is used too often as a place of safety under the provisions of Section 136 in the absence of more suitable hospital provisions.

The developments of police station diversion schemes have shown success in terms of diverting people with mental disorder away from the criminal justice system at a much earlier stage. Yet implementation of such schemes is not always in place. Those who are diverted appear to be a different population from those seen at a later stage of proceedings of the criminal justice system, such as magistrates' courts or prisons. There is a need to develop better integrated services to achieve more successful diversion from police custody where appropriate. More research is needed to understand why Black and minority ethnic groups are overrepresented among people with mental disorders who present via the police.

Psychiatrists, and often other healthcare professionals, are so commonly involved in the assessment and management of mentally disordered detainees in police custody that formal training should be paramount.

MCQs

-

1 Psychiatrists:

-

a are rarely called to police stations to perform assessments

-

b are often required to assess an individual's fitness to be interviewed

-

c must be at consultant level to assess detainees

-

d are requested by the police only to assess people detained under Section 136 of the Mental Health Act

-

e are the only people who can request an appropriate adult.

-

-

2 People with mental disorder:

-

a rarely present to services via the police

-

b can be detained under Section 136 from their own homes

-

c must be deemed to be in need of immediate care and control before they can be detained under Section 136

-

d have to be diagnosed with a mental illness by the police before they can be detained under Section 136

-

e never need an appropriate adult when interviewed by the police.

-

-

3 Section 136:

-

a allows for treatment of the detainee against their will

-

b ceases to operate once the person has been deemed by the psychiatrist as not having a mental disorder

-

c requires lots of statutory forms to be filled in

-

d is used to detain proportionally fewer people from Black and minority ethnic groups than White people

-

e allows for detention in hospital for 28 days.

-

-

4 In respect of fitness to be interviewed:

-

a people with intellectual disability are at risk of providing unreliable information

-

b people with mental illness are never fit to be interviewed

-

c it is essentially an assessment of capacity

-

d psychiatrists should never ask for an appropriate adult

-

e is only ever requested by a Crown Court

-

-

5 Substance misuse:

-

a is rare among those detained by the police

-

b is rarely found in people who die in police custody

-

c is sufficient grounds by itself to detain someone under the Mental Health Act

-

d can lead to an individual being unfit to be interviewed

-

e is decreasing as a problem in those detained by the police.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | f | a | f | a | f | a | t | a | f |

| b | t | b | f | b | t | b | f | b | f |

| c | f | c | t | c | f | c | f | c | f |

| d | f | d | f | d | f | d | f | d | t |

| e | f | e | f | e | f | e | f | e | f |

FIG 1 Pathways of people with mental disorder coming into contact with the police.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.